Abstract: In the summer of 2010, Taiwanese-based Foxconn Technology Group-the world’s largest electronics manufacturer-utilized the labor of 150,000 student interns from vocational schools at its facilities all over China. Foxconn is one of many global firms utilizing student intern labor. Far from being freely chosen, student internships are organized by the local state working with enterprises and schools, frequently in violation of the rights of student interns and in violation of Chinese law. Foxconn, through direct deals with government departments, has outsourced recruitment to vocational schools to obtain a new source of student workers at below minimum wages. The goals and timing of internships are set not by student educational or training priorities but by the demand for products dictated by companies. Based on fieldwork in Sichuan and Guangdong between 2011 and 2012 and follow-up interviews in 2014, as well as analysis of the Henan government’s policies on internships, we find that the student labor regime has become integral to the capital-state relationship as a means to assure a lower cost and flexible labor supply for Foxconn and others. This is one dimension of the emerging face of Chinese state capitalism.

Keywords: student labor, state capitalism, internship, vocational school, Foxconn Technology Group

I. Introduction

“My original plan was to seek an internship at Huawei Technologies, but our teacher persuaded my whole class of 42 students to intern at Foxconn Technology Group,” a student from a vocational school in Sichuan’s Mianyang city recalled. Under pressure from the Sichuan government to fulfill a quota for interns at Foxconn in 2010, the teacher was directed to recruit entire classes and overcome student objections to taking Foxconn internships. “During the night shift, whenever I look out in that direction [pointing to the west], I see the big fluorescent sign of Huawei shining bright red, and at that moment, I feel a pain in my heart,” she said before sinking into a long silence. Huawei (founded in Shenzhen as a private-sector firm in 1987) and Foxconn (founded in Taipei in 1974 and incorporated in Shenzhen as a Taiwanese-invested enterprise in 1988) have headquarters on opposite sides of the Meiguan Expressway in Longhua Town, Shenzhen City. Although neither the intern nor we can verify whether the internship program offered by Huawei would have been any better than that at Foxconn, she regretted her inability to choose her internship site (Fieldwork in Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, April 2011).

Who are the interns? How are they recruited and managed at the workplace? In this article we show the processes by which companies, vocational schools, and local governments jointly carry out “internship programs” that turn large numbers of teenage students into factory workers. We attempt to explain the emergence of this student labor regime in the context of China’s rising manufacturing costs and intensified competition among companies for employees in global production. Analyzing the organization of student internships, we look into the pivotal role of transnational capital and its ability to secure privileged access to labor in negotiation with the Chinese state. The active cooperation of provincial and lower level governments in circumventing labor law restrictions, and ensuring corporate access to a lower cost and flexible supply of student labor (xueshenggong 學生工), is fundamental to the contemporary Chinese labor regime.

Our primary research is based on multiple fieldtrips to Foxconn’s largest assembly facilities in Sichuan (Chengdu City) and Guangdong (Shenzhen City) between 2011 and 2012, and follow-up visits in Shenzhen in August 2014, supplemented with inquiries made to senior company executives between December 2013 and April 2014.1 Drawing on interviews with 38 interns and 14 teachers, who were dispatched from eight vocational schools (based in Sichuan and Henan provinces) to Foxconn factories for internships, we also conducted documentary analysis of the Henan government’s major policies on student internships and employment. There has been scant scholarly attention to student interns as temporary or contingent labor, leaving unexamined an important dimension of the precarity of Chinese labor that is the product of the triangular relationship linking capital, the local state, and vocational schools in internship programs. In the following we review the changing labor market and ongoing legal reforms and structural transformation in China. We then present the findings of our study of the Foxconn internship program, and conclude by assessing the corporate and government responses to student labor abuses.

II. Student Labor in China

The re-emergence of labor markets under China’s reforms since the late 1970s has transformed the economy in step with Chinese and international investment and the privatization of numerous state enterprises. Employment in the manufacturing sector (relative to agriculture and the service industry) reached an unprecedented 15 percent of the economically active population in the mid-1990s. The percentage would have been even higher if the other eight to 14 percent of those employed in uncategorized industries were added (Evans and Staveteig 2009, 78). The increase in industrial workers was mainly drawn from the hundreds of millions of rural migrants who, in the wake of de-collectivization, were absorbed into booming township and village enterprises and export-oriented privately-owned factories, along with state and collective enterprises. However, the labor rights and interests of many internal migrants were unprotected. It was not until July 1994, following tragic industrial fires and deaths and numerous abuses, that the government promulgated a Labor Law to regulate the complex labor relations of the market economy (Gallagher 2005, 2014; Ngok 2008; Liebman 2014). The law guarantees basic protections to all worker-citizens, regardless of household registration status or ownership type, such as entitlement to employment contracts, local minimum wages, overtime premiums, social insurance and retirement benefits, rest days, safe and healthy workplaces, and access to government-sponsored labor dispute resolution mechanisms. Despite the national labor compliance requirements, employers systematically “ignored the law with impunity because of the lack of effective implementation and enforcement by local regulatory or supervisory organizations, including the trade union, the local labor bureau and the courts” (Gallagher and Dong 2011, 44).

When structural reforms and privatization accelerated in the 1990s and following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, many small and medium state-owned enterprises lost out in the fierce new competition. Laid-off workers, especially those who were relatively young, joined the rank and file of rural migrants to toil in the “world factory,” facing great uncertainties in a more liberalized economy (Solinger 2009; Blecher 2010; Andreas 2012; Hurst 2009, 2015). As of 2005, Chinese manufacturing wages as a percentage of US wages, compared to those of Japan and East Asian Tigers like South Korea and Taiwan in the early years of their economic takeoffs, had remained consistently low (Hung 2008, fig. 1, 2009, fig. 5). Private companies as well as restructured state enterprises have generally offered fixed-term employment contracts, effectively ending a lifetime “iron rice bowl” tenure that had been prevalent in large urban state enterprises. Other employing units, however, failed to provide labor contracts, minimum statutory wages, or welfare benefits, generating worker grievances and resistance (Chan 2001; Pringle 2011; Elfstrom and Kuruvilla 2014; Zipp and Blecher 2015). In the face of increasing worker lawsuits and collective protests since the mid-1990s, the Chinese government was compelled to expand legal reforms to ensure minimally acceptable social and labor standards as a means to alleviate the growing tensions between legitimacy and profitability (Lee 2007; Lee and Zhang 2013; Chen 2012; Friedman 2014).2

From the mid-2000s, as a result of growing worker demands for better conditions, tightening labor markets due to demographic changes, and Beijing government measures to stimulate domestic consumption such as boosting statutory minimum wages and abolishing agricultural taxes, wages have been rising (Chu and So 2010; Eggleston et al. 2013; Davis 2014; Whyte 2014; Naughton 2014). Firms were increasingly pressured to cut costs and to cope with fluctuations in production orders by hiring temporary workers, including student interns (also termed student apprentices or trainees) and agency laborers (also known as dispatched workers, who signed contracts directly with privately-run or government-operated agencies but providing services to client companies). In the seven large state-owned and Sino-foreign joint-ventured automobile assembly factories that she surveyed, Lu Zhang (2015) found that the number of temporary workers ranged from one- to two-thirds of the total workforce during fieldwork in the mid-to-late 2000s. Downward cost pressure in business competition, particularly during the 2008 global financial crisis, eroded the wages and benefits as well as job security of regular workers who have not yet been displaced by temporary laborers. The latter’s per capita cost averages only one-fourth to one-third of the former’s (Park and Cai 2011, 33-35; Zhou 2013, 362-63). Unequal treatment of the temporary and regular workers performing identical production tasks created a two-tiered employment system. This system engendered worker conflicts and social divisions. As Eli Friedman and Ching Kwan Lee (2010, 513) insightfully observe, this dual labor regime “is problematic not just from the perspective of the informal workers, but also from [that of] the regular workers, who will find it increasingly difficult to make collective demands on their employers.”

Agency workers, who were long excluded from national legal protection prior to the implementation of the significant Labor Contract Law on 1 January 2008, eventually gained access to basic employment rights, if only honored on the books. Under the new law, under which hiring agencies and client firms share joint legal responsibilities, agency workers are supposed to receive the same pay for doing the same work as directly employed workers. Moreover, they are assumed to take only “temporary, auxiliary, and substitute” posts, thereby placing certain limits on informalization while maintaining labor and organizational flexibility (Chan 2009; Harper Ho 2009; Wang et al. 2009; Cui et al. 2013; Gallagher et al. 2015; Zhang 2015, chap. 7). It is important to note, however, that the 2008 law did not cover interning students. Interns, who are not, after all classified as workers, can be laid off without severance pay and 30 days’ prior notice to which employees are entitled. They continue to possess fewer legal rights than agency or regular workers even when they are directly recruited and assigned to the same tasks (Pun and Chan 2012, 2013; Chan and Selden 2014; Pun et al. 2014; Chan et al. 2013, 2015).

The vulnerability of interns as laborers, including both those who are unpaid and those who are under-paid, has recently drawn discussion centering on the applicability of relevant national and international laws. Earl Brown and Kyle deCant (2014), in their provocative essay “Exploiting Chinese Interns as Unprotected Industrial Labor,” ask whether interns-who are not legally defined as employees under Chinese law-are in practice provided equal labor rights at work, and whether the internship experience benefits the intern. The controversy is not just about poor management and lack of educational content in some internship programs, as documented in the 2010 OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) review report on China’s development of vocational education and workplace-based internship training (Kuczera and Field 2010, 18-27). It is ultimately about the well-being of, and fundamental fairness to, student intern workers. While the Chinese state has not fully recognized interns as workers, it has granted them certain rights under the domestic legal framework. Brown and deCant (2014, 195) compellingly assert: “When these programs [at Foxconn, Honda, and other workplaces] are devoid of any relevant educational component and maintained solely for the benefit of the employer’s bottom line, these interns should be afforded the full protection of China’s labor laws.” We aim to extend the legalistic debates by evaluating the role of the local state as a direct agent in a capitalist development process in which student labor governance is becoming an integral and substantive part. As we will see, at stake is not a mere legal technicality; it is the dynamism of a capital-state alliance that charts the role of student labor with important implications both for student (mis)education and the corporate bottom line.

From the national to the global level, the promulgation of a set of non-binding transnational labor and environmental standards has been among the key corporate responses to sweatshop charges made by workers and their supporters in many countries (Ross 2004; Smith et al. 2006; Litzinger 2013; Locke 2013; Lüthje et al. 2013; Ruggie 2013). Workers-including student interns-are subjected to the pressure of buyers in multi-layered production networks. Image-conscious companies, in response to charges of labor abuse in factories that produce their products, pledge to adhere to good labor practices in global production, such as respecting the rights of “student workers” in China (Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition [EICC] 2014, 44). Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC), the membership-based industry association representing Apple and Foxconn and 100-plus other companies worldwide, has asserted that, “In the past 10 years we have seen that consistent auditing, clearer guidelines, greater transparency and a Code of Conduct can play important roles” in regulating “student working hours, wages, [and] health and safety gaps” (EICC 2015, 4). In China’s high-tech electronics manufacturing, researchers including ourselves have just begun to assess the impact of corporate codes of conduct on workers’ conditions.

In a nutshell, we locate student labor at the heart of key industries, notably electronics, in globalized China. In contrast to the approach of Lu Zhang in Inside China’s Automobile Factories (2015, chaps. 5-6), who did not distinguish between interning students and agency workers in her categorization of “temporary workers,” a group contrasted to “formal workers,” we aim to understand the distinctive character of student interns in China’s international political economy. Accordingly, we examine the central role of three parties in the recruitment and control of students during the internship period, namely, factory managers, school teachers, and local officials. Our major goal is to explain the systemic deployment of student interns in industrial production through a study of Foxconn’s practice, thereby contributing to deeper understanding of the massive use of student interns on worker fragmentation among Chinese workers.

III. The Foxconn Internship Program

With more than one million employees, Foxconn is the world’s largest industrial employer (DeCarlo 2014) and probably maintains the world’s largest internship program. The Foxconn internship program, which brought in as many as 150,000 young students during the peak production months in summer 2010-approximately 15 percent of the company’s workforce (Foxconn Technology Group 2010a)-and which continues to hire new interns across China at present, dwarfs Disney’s College Program, which received more than 50,000 interns cumulatively over 30 years from college partners in the United States and abroad (Perlin 2011, 6). How is the capital-state-school coalition behind the Foxconn internship program organized?

Foxconn is a key node in the Asian and global production networks, where the processing of components, final assembly, and shipment of finished products to world consumers continues around the clock 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Inside Foxconn there are more than a dozen “business groups” (shiyequn 事業群), which compete on speed, quality, efficiency, engineering services, and added value to maximize profits. In one of these business groups, iDPBG (integrated Digital Product Business Group), which produces exclusively for Apple, 28,044 student interns worked alongside workers in Shenzhen in 2010-a six-fold increase from 4,539 in 2007. They were recruited from “more than 200 secondary vocational schools” (Foxconn Technology Group 2010b, 23). At the company’s 30-plus manufacturing mega-complexes across China (see Figure 1), workers and student interns toil day and night to churn out iPhones, iPads, and other electronic products for Apple and other IT corporations. Following Chinese government stimulus-led growth and economic recovery, as well as large-volume orders, in 2010, Foxconn registered a 53 percent year-on-year increase in revenues to US$95 billion (3 trillion NTD) (Foxconn Technology Group 2011, 4). Student interns, among assembly-line workers, played an indispensable role in corporate expansion.

China has more than 13,300 registered vocational schools and colleges (Xinhua 2015). In 2014, approximately 18 million full-time students were enrolled in secondary vocational schools across the country. The government projects an increase in vocational school enrollment to 23.5 million by 2020 (not including those in vocational colleges or adult vocational education) (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2010a, table 1). Upon completing nine years of compulsory education, students can compete to continue their studies in general track high schools or enroll in vocational institutions. The age of admission to standard three-year vocational schools is often as young as 15. While students in high schools are prepared for university entrance, those in vocational schools are trained for skilled work or higher vocational education.

Vocational schools offer employment-oriented courses for first- and second-year students. During their third year, when they are 17 to 18 years old, students are expected to intern at enterprises that are “directly relevant to their studies” (Ministries of Education and Finance of the People’s Republic of China 2007, art. 3). However, our interviews revealed that Foxconn not only recruits students regardless of their field of study, but also often much earlier than is legally allowed (that is, in their first and second years of vocational studies). In our sample, only eight of the 38 student interns were in their final year. Their average age was 16.5, just above the national statutory minimum working age of 16.

The Working Conditions of Student Interns

The duration of the Foxconn internship programs we studied during fieldwork in 2011 and 2012 ranged from three months to one year. From the beginning of her internship, Liu Siying3, the final-year student aspiring to a meaningful learning opportunity whom we met at the opening of this article, was “tied to the PCB [printed circuit board] line attaching components to the product back-casing.” In her words, “it required no skills or prior knowledge.” Students were assigned to a one-size-fits-all internship at Foxconn factories, which involved repetitive manual labor divorced from their studies and interests.

China’s leaders seek to boost labor productivity through expanded investment in vocational skill training (Woronov 2011; Hansen and Woronov 2013; Ling 2015). At Foxconn, interns were placed on assembly lines to work illegally long shifts of ten to 12 hours, six to seven days a week. Article 5 of the 2007 Administrative Measures for Internships at Secondary Vocational Schools (Ministries of Education and Finance of the People’s Republic of China 2007) states that “interns shall not work more than eight hours a day,” and the 2010 Education Circular (Clause 4) specifies that “interns shall not work overtime beyond the eight-hour workday” (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2010b). Not only must interns’ shifts be no more than eight hours, all their training activity is required to take place during daytime to ensure students’ safety and physical and mental health, in line with the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors (2013).4 In reality, interns ranging in age from 16 to 18 were subjected to the same working conditions as regular workers, including alternating day and night shifts and extensive overtime, defying the letter and the spirit of the education law.

A typical comment by interns, their hopes for gaining technical knowledge dashed, underlines the harsh reality of life on the line: “We’re sent to do trivial tasks like checking iPad screens and cleaning the product surface … we’re frustrated at repeating the same boring work all day” (Interviews on 19 March 2011; 18 December 2011). Foxconn Global Social and Environmental Responsibility Committee Executive Director, Martin Hsing, has defended the internship program, saying that “it meets the needs and expectations of the interns,” even when the educational value of internship is reduced to assembly-line labor, pure and simple. He emphasized that school participation is “voluntary” and that interns are “free to terminate their internship at any time;” more importantly, the company has “specific policies to ensure that [the internship program] is implemented in full accordance with China law” and its “own Code of Conduct” (Foxconn Technology Group 2013). Several students told us that they phoned their parents after the first week of the internship asking them to pressure Foxconn managers to immediately “release the interns.” They failed. They were told that they “risked not being able to graduate” if they refused internships at Foxconn (Interviews on 3 March 2011; 1 April 2011; 20 January 2012).

At Foxconn, student interns are paid. As of January 2011, while student interns and entry-level workers had the same starting wage of 950 yuan/month (USD $154 / GBP £100 / EUR €128), only employees could receive a skill bonus of 400 yuan/month (USD $65 / GBP £43 / EUR €54). Interns were not entitled to have their skills assessed in order to qualify for the bonus (see Figure 2). China’s Vocational Education Law, effective 1 September 1996, states that students participating in vocational education programs “shall be paid properly for their work” (Article 37, shidang de laodong baochou 適當的勞動報酬) (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 1996). Similarly, the 2007 Administrative Measures for Internships at Secondary Vocational Schools stipulate that employers should “pay reasonably for the labor of interns” (Article 8, heli de shixi baochou 合理的實習報酬). Maintaining that student interns are not employees-even when they perform work identical to that of production workers-Foxconn does not enroll interns in government-administered social security, which covers medical insurance, work injury insurance, unemployment benefits, maternity insurance, and old age pensions, nor in a housing provident fund (known collectively as “wu xian yi jin” 五險一金). By dispensing with all of these benefits, the company saves money.

For the period of our investigation, Foxconn claimed to have provided “work-related injury and health insurance” for all interns (quoted in Fair Labor Association 2012, 10), but our interviewed interns said they had received no information about an insurance policy. A quick look at the math reveals that, in 2015, assuming a total of 150,000 student interns working in various Foxconn factories during one month in the peak season, the savings from not providing them with welfare benefits is roughly 150,000 persons × 300 yuan = 45,000,000 yuan (economic conditions and statutory minimum wages vary substantially across China; we use the lower end of 300 yuan/month per person for this illustration5). While this is a simplified exercise, it conveys a good sense of employer savings for just one month; considering that many interns work for a full year, the annual savings must be far greater.

Cost cutting is especially imperative in electronic manufacturing where profit margins are thin (Kraemer et al. 2011; Lüthje et al. 2013). In recent years, state minimum wages have steadily increased and companies have faced pressure to raise wages to retain workers, particularly a young cohort, who frequently changed jobs in an attempt to get better pay and benefits. National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (2014, fig. 1) reported that average total income of rural migrant workers had risen steadily following the economic recovery in 2009, reaching unprecedented 2,609 yuan/month in 2013, a 13.9 percent increase from the previous year. However, “speed, not just cost,” might be “the killer attribute” that gives Foxconn and other large manufacturers “the winning edge to remain competitive” (Dinges 2012). Pressure from brand-name buyers to stay responsive to consumer demand is strong (Hamilton et al. 2011). Accordingly, Foxconn translates production requirements for fast time-to-market and high quality into increased work pressure and longer hours. In a rare reference to the production pressures that Apple and its competitors apply, Foxconn CEO’s Special Assistant Louis Woo explained his company’s perspective on overtime in an April 2012 American media program (Marketplace 2012):

The overtime problem-when a company like Apple or Dell needs to ramp up production by 20 percent for a new product launch, Foxconn has two choices: hire more workers or give the workers you already have more hours. When demand is very high, it’s very difficult to suddenly hire 20 percent more people. Especially when you have a million workers-that would mean hiring 200,000 people at once.

Woo’s statement indicates that, when faced with soaring demand from Apple, Dell, and other electronics brands, Foxconn’s first response is to impose compulsory overtime on its existing labor force. However, it also tries to hire more people to respond seamlessly to corporate demands for rush orders. Recruitment through vocational schools is an efficient way to pick up tens of thousands of new workers at once, who are purportedly hired in the name of skills training and school-business cooperation (xiaoqi hezuo 校企合作).

In Shenzhen’s Longhua Cultural Square, student intern Zhang Lintong, 16, talked about school life and music. He told us he admires the 19th century Russian realist artist Ilya Repin and praised The Song of the Volga Boatmen, which reminds him of Repin’s seminal painting Barge Haulers on the Volga.6 Barge Haulers depicts a foreman and ten laboring men hauling an enormous barge upstream on the Volga. The men seem on the verge of collapse from exhaustion. The lead hauler’s eyes are fixed on the horizon. The second man bows his head into his chest and the last one drifts off from the line, a dead man walking. The haulers, dressed in rags, are tightly bound with leather straps. The exception is the brightly clad youth in the center of the group, who raises his head while fighting against his leather bonds in an effort to free himself from toil. “I often dream, but repeatedly tear apart my dreams; like a miserable painter, tearing up my draft sketches…I’m not interested in assembling iPhone parts. It’s exhausting and boring. I want to quit. But I can’t,” Lintong sighed (Interview on 29 November 2011).

All 14 female and male teachers we interviewed were aware that the Foxconn program violated the purpose of internships, which are mandated to provide an integral part of students’ education and skills training. Fearing punishment from the school, however, teachers and students played their parts in the charade called internship. The teachers reported for duty at the company administrative building from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Friday. They were housed in the factory dormitories throughout the internship. Only one teacher expressed criticisms of the internship system in the course of our fieldwork. Mr. Tian, a Sichuanese in his 40s, was a Chinese literature teacher with more than two decades of teaching experience. “My daughter is 17 years old, my only daughter. She’s now preparing for the national college entrance exam. No matter what the result is, I won’t let her come to intern, or work, for this company.” And yet he told us that “paid internships at Foxconn were one of the main attractions for students attending his school.” He also admitted, however, that “at Foxconn, there’s no real learning through integration of classroom and workshop. The distortion of vocational education in today’s China is deeply rooted” (Interview on 16 December 2011).

Student Internship Recruitment through Government and School Mobilization

Foxconn, given its powerful market position, gains access to numerous resources with strong government support all over China. In the years since the magnitude 7.9 earthquake that struck Sichuan in May 2008, killing 87,150 people and leaving 4,800,000 homeless, the provincial government has redoubled efforts to attract investments to fund reconstruction. Zhuang Hongren, Foxconn’s chief investment officer, pledged to “help Chengdu to become an unshakeable city” in world electronics (quoted in Sichuan Provincial People’s Government 2011). In response, local officials subsidized transportation services and provided numerous benefits for the company. Foxconn employees now commute to work in public buses that have been dedicated to the exclusive use of Foxconn (Fieldwork in Pi County, Chengdu City, March 2011). Government-printed banners on the sides of the buses read, “Use fighting spirit against earthquakes and natural disasters to provide transportation for Foxconn” (yong kangzhen jiuzai de jingshen, nuli wancheng Fushikang baoche yewu 用抗震救災的精神,努力完成富士康包車業務). Foxconn’s economic influence has become so great that CEO Terry Gou is widely known among workers as the “Mayor of ‘Foxconn City'” in Chengdu, provincial capital of Sichuan, southwest China.

Manager Zhu, a 31-year-old college graduate, joined the human resources department of Foxconn Chengdu on its opening in October 2010 after seven years in a small state-owned factory, was chiefly responsible for liaison linking government, vocational schools, and Foxconn. He explained (Interview on 14 December 2011):

Over the past year, I held monthly meetings with government leaders responsible for the “Number One Project” [yihao gongcheng 一號工程] tailored for Foxconn. Over a few drinks and shared cigarettes, our colleagues and local government officials regularly updated each other on the company’s recruitment schedules, thereby establishing a good working relationship.

The Sichuan provincial government prioritized helping Foxconn as its “Number One Project.” It offered Foxconn partial funding to construct its gigantic production complex and 18-story dormitories. In addition to the construction projects, it undertook large-scale recruitment of student interns and workers at new Foxconn factories (there are two mega production sites of Foxconn Chengdu), leaving other Taiwanese manufacturing competitors such as Wistron and Compal far behind (Global Times 2012). Local education bureaus pitched in by compiling and updating lists that identify vocational schools suitable for linking to Foxconn internship programs. All qualified schools were required to participate in recruitment.

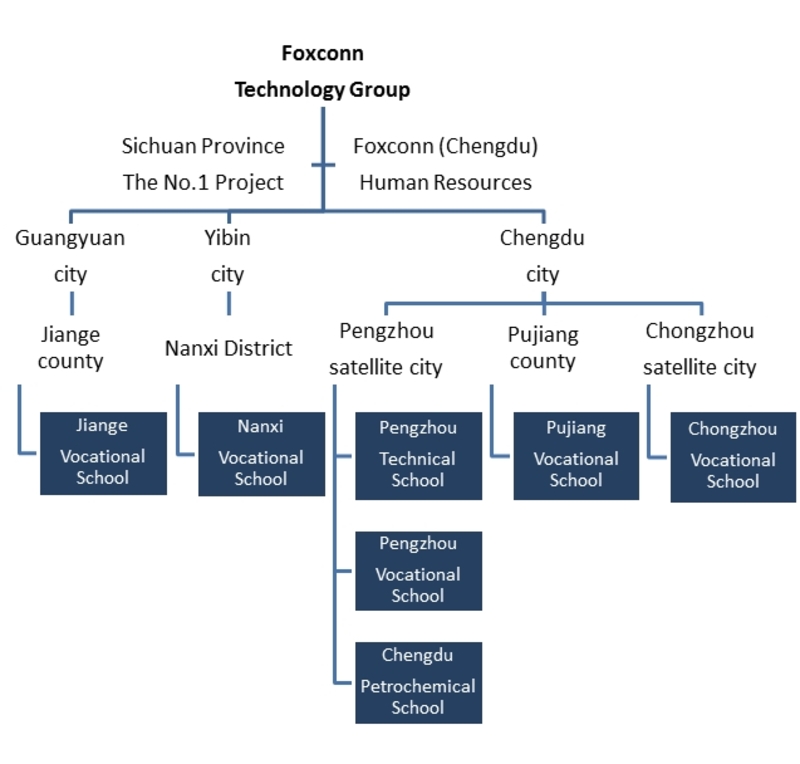

To assure the vocational schools’ cooperation, governments disburse funds to those that fulfill company targets for the number of student interns. If schools fail to meet human resources requirements, education bureaus withhold funds (Interview with a township government official in Chengdu City, 17 December 2011). Foxconn has taken advantage of this system to extend its labor recruitment networks to schools, where it draws on the assistance of local officials and teachers to utilize student labor. Figure 3 shows how Foxconn in Sichuan province draws up plans for student labor recruitment, then top-level government officials lead work teams across different administrative levels (city, county, district, township and village) to meet the deadlines and quotas, with the cooperation of the vocational schools under their jurisdiction.

All production workers, including student interns, at Foxconn Chengdu are engaged in making iPads exclusively for Apple. Between September 2011 and January 2012 (a school semester), in Foxconn’s Chengdu factories, more than 7,000 students-approximately ten percent of the labor force-were working on the assembly line (Interviews with human resources managers and teachers in December 2011 and January 2012). One of the participating schools, Pujiang Vocational School, sent 162 students on 22 September 2011 to undertake three-month internships that were subjected to extension in accordance with iPad production needs. The large Pengzhou Technical School signed up 309 students, accompanied by three male and three female teachers during the entire internship. This is typical of the 1:50 teacher-student ratio maintained throughout the Foxconn Chengdu internship program in 2011-2012. Contrary to our findings, the Apple-commissioned factory inspector Fair Labor Association “found no interns had been engaged at [Foxconn] Chengdu since September 2011″ (our emphasis) (Fair Labor Association 2013, 5).7

Government officials support the timely fulfillment of labor recruitment assignments for Foxconn by doing public relations work to improve the company’s image. The targets include students and fresh graduates. A township official-in-charge elaborated, “We were tasked by upper level governments to eliminate negative social attitudes toward Foxconn after the [2010] suicide wave”8 (Interview on 14 December 2011). The main contents of student labor recruitment are Foxconn’s corporate development, its economic and technological strength, and its expansion prospects. The government team deploys messages “across the internet, radio, television, posters, blogposts, leaflets, telephone calls, door-to-door visits, and the mail to publicize Foxconn’s culture, and guide recruitment targets in correct thinking and understanding” (The People’s Government of Guangyuan City [Sichuan] 2011a). Villages, towns, and schools are saturated with propaganda to assure that Foxconn achieves the status of a household name. The division of labor is summarized as follows (Interview with a township government official in Chengdu City, 16 December 2011):

1. The Human Resources and Social Security Department makes recruitment a top priority.

2. The Education Department arranges school-business cooperation, ensures that the number of graduates and interns meets the assigned goal, and arranges for their transportation on schedule and properly supervised by teachers.

3. The Finance Department ensures that recruitment is adequately funded.

4. The Public Security Department completes job applicants’ background investigations.

5. The Transportation Department assures appropriate transport capacity and safety.

6. The Health Department provides pre-employment physical examinations.

7. Other relevant departments ensure that recruitment progresses smoothly.

Foxconn obtains wealth of resources from multiple government departments to enhance its cost-competitiveness and business capacity while assuring an abundant supply of workers at a time of tightened labor markets. Indeed, in the past 30-plus years, preferential treatment by local governments has increased capital mobility and facilitated the growth of transnational corporations, first in southeast coastal regions and then in interior cities (McNally 2004; Leng 2005; Selden and Perry 2010). What is new is the outreach to vocational schools to tap student labor through a partnership of capital and state. One municipal government actually conducts investigations of departments that “do not complete 50 percent of monthly tasks,” pushing for a 100 percent completion rate of the recruitment quota handed down by Foxconn (The People’s Government of Guangyuan City [Sichuan] 2011b).

“In Chengdu,” Andrew Ross (2006, 218) concludes from his research on global IT service outsourcing to China that “it was impossible not to come across evidence of the state’s hand in the fostering of high-tech industry.” From Sichuan to central China’s Henan province, provincial governments have similarly channelled financial and administrative resources to support Foxconn hiring. In June 2010, the Zhengzhou City Education Bureau directed all vocational schools under its jurisdiction to dispatch students 1,000 miles away to Foxconn’s Shenzhen factories for employment and/or internships. This step was taken to make sure students would complete their training in time for the August opening of a new manufacturing base in Zhengzhou, provincial capital of Henan. Foxconn Zhengzhou exclusively assembles iPhones for Apple. The opening passage of the government notification to all education units reads (Zhengzhou City Education Bureau (Henan) 2010):

To promote the city’s vocational education, accelerate the pace of educational development, deepen school-business cooperation, strengthen customized training, and promote industry, it has been decided to launch an employment (internship) partnership with Foxconn Technology Group, and to arrange for all vocational school students to work (intern) at Foxconn Shenzhen.

Specifics of the sweeteners offered to Foxconn include the following (Henan Provincial Poverty Alleviation Office 2010.):

1. Implementing a policy of rewards for job introductions at the standard rate of 200 yuan per person from the designated government employment fund.

2. Giving every successful worker (or intern) a 600-yuan subsidy from the designated government employment fund.

The Henan provincial government, using taxpayers’ money, pays for incentives to schools or labor agencies (“the job introduction fee” of 200 yuan/person) that arrange for employment and/or internships at Foxconn. In August and September 2010, local government officials divided the 20,000-recruit goal among 23 counties and cities (each new worker/intern receives 600 yuan). For the targeted recruitment of 20,000 persons, the government bill would be 16,000,000 yuan (= 20,000 persons × (200 + 600) yuan). Each city or county government was assigned specific recruitment targets, with quotas within each district subdivided down to villages and towns. Table 1 shows the number of new Foxconn recruits that each of the 23 localities was ordered to produce. From this moment, student internships were transformed into a government-organized activity in the service of a private employer (see also, Henan Provincial Education Department 2010).

Government Recruitment Assignments for Foxconn, Henan

| Name | Targets for August 2010 (persons) | Targets for September 2010 (persons) | Total (persons) | |

| 1 | Xinyang | 1,000 | 1,000 | 2,000 |

| 2 | Zhoukou | 940 | 940 | 1,880 |

| 3 | Luoyang | 850 | 900 | 1,750 |

| 4 | Nanyang | 850 | 850 | 1,700 |

| 5 | Shangqiu | 850 | 850 | 1,700 |

| 6 | Zhumadian | 850 | 850 | 1,700 |

| 7 | Puyang | 750 | 700 | 1,450 |

| 8 | Xinxiang | 680 | 680 | 1,360 |

| 9 | Anyang | 650 | 650 | 1,300 |

| 10 | Pingdingshan | 550 | 550 | 1,100 |

| 11 | Kaifeng | 500 | 500 | 1,000 |

| 12 | Zhengzhou | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| 13 | Hebi | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| 14 | Jiaozuo | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| 15 | Xuchang | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| 16 | Luohe | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| 17 | Sanmenxia | 200 | 200 | 400 |

| 18 | Gushi County, Xinxiang | 100 | 100 | 200 |

| 19 | Jiyuan | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| 20 | Dengzhou City, Nanyang | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| 21 | Yongcheng City, Shangqiu | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| 22 | Xiangcheng City, Zhoukou | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| 23 | Gongyi City, Zhengzhou | 30 | 30 | 60 |

| Total | 10,000 | 10,000 | 20,000 |

Source: Henan Provincial Poverty Alleviation Office 2010.

Student interns-cheap, youthful, and productive-are a new source of labor that is growing larger in step with the expansion of vocational education. Steven McKay in Satanic Mills or Silicon Islands concludes that high-tech commodity producers “focus their labor concerns on cost, availability, quality, and controllability” to enhance profitability (2006, 42, italics original). On 1 November 2011, Han Chinese and Tibetan student interns got into a brawl during working hours. The incident sounded an alarm and a vice principal from one of the participating vocational schools arrived on the scene the next day to “look after his students,” reported interviewee Teacher Jiang. He added, “All of the few dozen students were laid off. Foxconn demanded that the schools concerned immediately ‘take back the bad students’ to prevent any disruption to work” (Interview on 15 December 2011). The assistance of the vice principal in removing the interns to whom Foxconn objected reveals other dimensions of how the schools and the enterprise cooperate in exercising dual control over students (Smith and Chan 2015). Psychosocial behaviour, such as playing video games all night and not going to work on time, as well as slowing down due to loss of motivation to work hard, however, continued. Foxconn’s presentation of Outstanding Student Intern Awards-also known as the “hardworking bee” prize-failed to instill stronger commitment and loyalty among interns who perceived the internship as squandering their education and found the work demeaning.

None of the 38 interviewed interns expressed interest in working for Foxconn after graduation. If they were interested in assembly line jobs, they would have started working straight away after finishing middle school rather than seeking specialized training in multiple fields. “Come on, what do you think we’ve learned standing for more than ten hours a day manning the machines on the line? What’s an internship? There’s no relation to what we study in school. Every day is just a repetition of one or two simple motions, like a robot,” Lintong emphasized (Interview on 29 November 2011).

IV. Conclusion

If the Chinese government’s goal is to encourage workforce preparedness by investing in vocational training, with student internships as a core component, the policy is a failure. Foxconn has shifted hiring costs onto local governments and outsourced recruitment to vocational schools to obtain a flexible, low-cost labor supply. In this capital-state-school alliance, the incorporation of students into the workplace in the guise of internships has served the interests of capital, while generating intern protests over unfair and illegal treatment.9 Intense competition among localities to lure foreign investment has undermined enforcement of labor and educational laws. Notwithstanding significant Chinese legal reforms to date, there remains a deep-seated conflict between state legitimation and local accumulation, with the result that student workers’ rights and interests are sacrificed. Companies have continued to exploit the internal contradictions of the state to maximize their gains, and local states have bent education and labor rules and regulations to attract businesses. This is one important facet of China’s distinctive state capitalism.

Speaking of the dynamism of state-society relations, Ching Kwan Lee (2007, 17) “sees contradictions within different state imperatives and insists that state power is not independent of but rather constituted through its engagement with social groups in their acquiescence and activism, triggered by contradictory state goals and policies.” We observe that, under mounting public concerns of student worker abuses, including child labor hidden in the guise of interns at Foxconn’s labor-hungry factories (SACOM 2012), the Chinese central government has recently proposed new “Draft Rules on the Management of Vocational School Student Internships” (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2012). These rules, if vigorously implemented, would require that student internships have substantial educational content and work-skill training plans, along with comprehensive labor protections for teenage workers. As of December 2014, however, the draft rules still had not been issued (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2014), suggesting opposition from employers and their allies.

At the industry level, in an attempt to polish its corporate image, Apple (2013, 19) reiterated in January 2013 its standards for suppliers’ hiring of students: “Student working hours must comply with legal restrictions…. We’ve begun to partner with industry consultants to help our suppliers improve their policies, procedures, and management of internship programs to go beyond what the law requires.” Claiming to exercise corporate social responsibility in global supply-chain management, Apple never acknowledged its own culpability in imposing tight delivery schedules and high quality demands at the lowest possible prices (Chan et al. 2013, 2015; Chakrabortty 2013). Manufacturers, faced with buyers’ tight deadlines and ruthless demands, in turn place tremendous pressure on frontline workers including interns to retain contracts and stay profitable. In February 2014, Scott Rozelle, co-director of the Rural Education Action Program at Stanford University, announced a monitoring and evaluation program of student internships at the invitation of Apple in Apple’s China-based major suppliers (Rural Education Action Program 2014). As of our writing in August 2015, the findings were still not publicly available.

Ross Perlin in his book on American and European internship practices, Intern Nation, comments, “The very significance of the word intern lies in its ambiguity” (2011, 23, italics original). In the four years we have been working on this research, we have seen that the recruitment of interns as cheap and disposable labor at Foxconn has become routine practice that continues in the present day, and extends to many other companies such as Samsung and Lenovo (see also China Labor Watch 2014; Dou 2014). Schools, facing financial and political pressure, are unable to shield students from internships that violate the letter and spirit of the law. Business-friendly local authorities sponsor such internship programs through direct subsidies and administrative support to large corporations. In China, the student labor regime has become integral to its economic development, frequently at the sacrifice of all workers’ interests.

Acknowledgements

*This article is jointly published by The Asia-Pacific Journal and Asian Studies (Official Journal of the Hong Kong Asian Studies Association). Asian Studies 1(1): 69-98, September 2015, DOI: 10.6551/AS.0101.04

The authors would like to thank Asian Studies and The Asia-Pacific Journal editors and reviewers, as well as colleagues Amanda Bell, Jeffery Hermanson, Greg Fay and Debby Chan for their intellectual insights. An earlier draft of this paper entitled “Student Interns in China: Foxconn Internship through Government and School Mobilization” was presented at Pennsylvania State University in March of 2013 at the symposium “Global Workers’ Rights: Patterns of Exclusion, Possibilities for Change,” where Jenny Chan received constructive comments from organizers Mark Anner, Jill Jensen, Daniel Hawkins and many participants.

We acknowledge academic funding support from University of Oxford, University of London, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and Hong Kong Research Grant Council.

Recommended citation: Jenny Chan, Pun Ngai and Mark Selden, “Interns or Workers? China’s Student Labor Regime”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 36, No. 2, September 7, 2015.

Related articles

• Scott North, Limited Regular Employment and the Reform of Japan’s Division of Labor

• Pun Ngai, Shen Yuan, Guo Yuhua, Lu Huilin, Jenny Chan and Mark Selden, Worker-Intellectual Unity: Suicide, trans-border sociological intervention, and the Foxconn-Apple connection

• Holly H. Ming, Migrant Workers’ Children and China’s Future: The Educational Divide

• Jenny Chan, Ngai Pun and Mark Selden, The politics of global production: Apple, Foxconn and China’s new working class

• Stevan Harrell and Aga Rehamo, Education or Migrant Labor: A New Dilemma in China’s Borderlands

• Oguma Eiji and David Slater, From a ‘Dysfunctional Japanese-Style Industrialized Society’ to an “Ordinary Nation”?

• David H. Slater, The Making of Japan’s New Working Class: “Freeters” and the Progression From Middle School to the Labor Market

• Emilie Guyonnet, Young Japanese Temporary Workers Create Their Own Unions

• Jenny Chan, Pun Ngai, Suicide as Protest for the New Generation of Chinese Migrant Workers: Foxconn, Global Capital, and the State

References

Andreas, Joel. 2012. “Industrial Restructuring and Class Transformation in China.” In China’s Peasants and Workers: Changing Class Identities, edited by Beatriz Carrillo and David S. G. Goodman, 102-23. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Apple. 2013. “Apple Supplier Responsibility: 2013 Progress Report.”

Blecher, Marc. 2010. “Globalization, Structural Reform, and Labour Politics in China.” Global Labour Journal 1:92-111.

Brown, Earl V., Jr., and Kyle A. deCant. 2014. “Exploiting Chinese Interns as Unprotected Industrial Labor.” Asian-Pacific Law and Policy Journal 15:150-95.

Burawoy, Michael. 1985. The Politics of Production: Factory Regimes under Capitalism and Socialism. London: Verso.

Butollo, Florian, and Tobias ten Brink. 2012. “Challenging the Atomization of Discontent: Patterns of Migrant-Worker Protest in China during the Series of Strikes in 2010.” Critical Asian Studies 44:419-40.

Chan, Anita. 2001. China’s Workers under Assault: The Exploitation of Labor in a Globalizing Economy. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Chan, Chris King-Chi, and Elaine Sio-Ieng Hui. 2014. “The Development of Collective Bargaining in China: From ‘Collective Bargaining by Riot’ to ‘Party State-led Wage Bargaining.'” The China Quarterly 217:221-42.

Chan, Jenny. 2009. “Meaningful Progress or Illusory Reform? Analyzing China’s Labor Contract Law.” New Labor Forum 18:43-51.

Chan, Jenny. 2013. “A Suicide Survivor: The Life of a Chinese Worker.” New Technology, Worker and Employment 28:84-99.

Chan, Jenny, and Mark Selden. 2014. “China’s Rural Migrant Workers, the State, and Labor Politics.” Critical Asian Studies 46:599-620.

Chan, Jenny, and Ngai Pun. 2010. “Suicide as Protest for the New Generation of Chinese Migrant Workers: Foxconn, Global Capital, and the State.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 37-2-10, September 13.

Chan, Jenny, Ngai Pun, and Mark Selden. 2013. “The Politics of Global Production: Apple, Foxconn, and China’s New Working Class.” New Technology, Work and Employment 28:100-15.

Chan, Jenny, Ngai Pun, and Mark Selden. 2015. “Apple’s iPad City: Subcontracting Exploitation to China.” In Handbook of the International Political Economy of Production, edited by Kees van der Pijl, 76-97. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Chakrabortty, Aditya. 2013. “Forced Student Labor is Central to the Chinese Economic Miracle.” The Guardian, October 14.

Chen, Xi. 2012. Social Protest and Contentious Authoritarianism in China. New York: Cambridge University Press.

China Labor Watch. 2014. “Supplier Factory of Samsung, Lenovo Violates Rights of Children and Students.” August 28.

Chu, Yin-wah, and Alvin Y. So. 2010. “State Neoliberalism: The Chinese Road to Capitalism.” In Chinese Capitalisms: Historical Emergence and Political Implications, edited by Yin-wah Chu, 46-72. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cui, Fan, Ying Ge, and Fengchun Jing. 2013. “The Effects of the Labor Contract Law on the Chinese Labor Market.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 10:462-83.

Davis, Deborah S. 2014. “Demographic Challenges for a Rising China.” Dædalus: The Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 143(2):26-38.

DeCarlo, Scott. 2014. “The World’s 10 Largest Employers.” Fortune, November 12.

Dinges, Thomas. 2012. “To Win, Focus on Speed, Not Just Cost.” EBN (The Premier Online Community for Global Supply Chain Professionals), July 19.

Dou, Eva. 2014. “China’s Tech Factories Turn to Student Labor.” The Wall Street Journal, September 24.

Eggleston, Karen, Jean C. Oi, Scott Rozelle, Ang Sun, Andrew Walder, and Xueguang Zhou. 2013. “Will Demographic Change Slow China’s Rise?” The Journal of Asian Studies 72:505-18.

Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC). 2014. “Annual Report 2013.”

Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC). 2015. “Working to Eradicate Forced Labor in the Electronics Supply Chain.”

Elfstrom, Manfred, and Sarosh Kuruvilla. 2014. “The Changing Nature of Labor Unrest in China.” ILR (Industrial and Labor Relations) Review 67:453-80.

Evans, Peter, and Sarah Staveteig. 2009. “The Changing Structure of Employment in Contemporary China.” In Creating Wealth and Poverty in Postsocialist China, edited by Deborah S. Davis and Wang Feng, 69-82. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fair Labor Association. 2012. “Independent Investigation of Apple Supplier, Foxconn Report Highlights.”

Fair Labor Association. 2013. “Second Foxconn Verification Status Report.”

Foxconn Technology Group. 2010a. “Foxconn is Committed to a Safe and Positive Working Environment.” October 11.

Foxconn Technology Group. 2010b. “Hezuo, gongying: iDPBG zhaokai shixisheng zongjie ji biaozhang dahui” (“Win-Win Cooperation”: iDPBG Convenes the Intern Appraisal and Awards Ceremony). The Foxconn Bridgeworkers 183:23. [富士康科技集團。2010b. “合作.共贏”︰iDPBG召開實習生總結暨表彰大會. 鴻橋 183:23].

Foxconn Technology Group. 2011. “Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility Annual Report 2010.”

Foxconn Technology Group. 2013. “A 7-page company statement to authors.” December 31. Printed Edition.

Friedman, Eli. 2014. Insurgency Trap: Labor Politics in Postsocialist China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Friedman, Eli, and Ching Kwan Lee. 2010. “Remaking the World of Chinese Labour: A 30-Year Retrospective.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48:507-33.

Gallagher, Mary E. 2005. Contagious Capitalism: Globalization and the Politics of Labor in China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gallagher, Mary E. 2014. “China’s Workers Movement and the End of the Rapid-Growth Era.” Dædalus: The Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 143:81-95.

Gallagher, Mary E., and Baohua Dong. 2011. “Legislating Harmony: Labor Law Reform in Contemporary China.” In From Iron Rice Bowl to Informalization: Markets, Workers, and the State in a Changing China, edited by Sarosh Kuruvilla, Ching Kwan Lee, and Mary E. Gallagher, 36-60. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gallagher, Mary E., John Giles, Albert Park, and Meiyan Wang. 2015. “China’s 2008 Labor Contract Law: Implementation and Implications for China’s Workers.” Human Relations 68:197-235.

Global Times. 2012. “Officials Paying for Foxconn Hires.” August 16.

Hamilton, Gary G., Misha Petrovic, and Benjamin Senauer, eds. 2011. The Market Makers: How Retailers are Reshaping the Global Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hansen, Mette Halskov, and T. E. Woronov. 2013. “Demanding and Resisting Vocational Education: A Comparative Study of Schools in Rural and Urban China.” Comparative Education 49:242-59.

Harper Ho, Virginia E. 2009. “From Contracts to Compliance? An Early Look at Implementation under China’s New Labor Legislation.” Columbia Journal of Asian Law 23:33-107.

Henan Provincial Education Department. 2010. “Guanyu zuzhi zhongdeng zhiye xuexiao xuesheng fu Fushikang Keji Jituan dinggang shixi youguan shiyi de jinji tongzhi“ (Emergency Announcement on Organizing Secondary Vocational School Students for Internships at Foxconn Technology Group). September 4. [河南省教育廳. 2010. “關於組織中等職業學校學生赴富士康科技集團頂崗實習有關事宜的緊急通知.” 9月4日].

Henan Provincial Poverty Alleviation Office. 2010. “Guanyu Fushikang Keji Jituan zai Wosheng Pikun Diqu Zhaopin Peixun Yuangong Gongzuo de Tongzhi” (Announcement regarding Foxconn Technology Group worker recruitment and training in impoverished areas). July 14. [河南省扶貧辦. 2010. “關於富士康科技集團在我省貧困地區招聘培訓員工工作的通知.” 7月14日]. Printed Edition.

Hung, Ho-fung. 2008. “Rise of China and the Global Overaccumulation Crisis.” Review of International Political Economy 15:149-79.

Hung, Ho-fung. 2009. “America’s Head Servant? The PRC’s Dilemma in the Global Crisis.” New Left Review 60:5-25.

Hurst, William. 2009. The Chinese Worker after Socialism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hurst, William. 2015. “Grasping the Large and Releasing the Small: A Bottom-Up Perspective on Reform in a County-Level Enterprise.” In Local Governance Innovation in China: Experimentation, Diffusion, and Defiance, edited by Jessica C. Teets and William Hurst, 103-16. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kraemer, Kenneth L., Greg Linden, and Jason Dedrick. 2011. “Capturing Value in Global Networks: Apple’s iPad and iPhone.”

Kuczera, Malgorzata, and Simon Field. 2010. “Learning for Jobs: OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training-Options for China.”

Lee, Ching Kwan. 2007. Against the Law: Labor Protests in China’s Rustbelt and Sunbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lee, Ching Kwan, and Yonghong Zhang. 2013. “The Power of Instability: Unraveling the Microfoundations of Bargained Authoritarianism in China.” American Journal of Sociology 118:1475-508.

Leng, Tse-Kang. 2005. “State and Business in the Era of Globalization: The Case of Cross-Strait Linkages in the Computer Industry.” The China Journal 53 (January): 63-79.

Liebman, Benjamin L. 2014. “Legal Reform: China’s Law-Stability Paradox.” Daedalus: The Journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 143:96-109.

Ling, Minhua. 2015. “‘Bad Students Go to Vocational Schools!’: Education, Social Reproduction and Migrant Youth in Urban China.” The China Journal 73:108-31.

Litzinger, Ralph A. 2013. “The Labor Question in China: Apple and Beyond.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 112:172-78.

Locke, Richard M. 2013. The Promise and Limits of Private Power: Promoting Labor Standards in a Global Economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lüthje, Boy, Stefanie Hürtgen, Peter Pawlicki, and Martina Sproll. 2013. From Silicon Valley to Shenzhen: Global Production and Work in the IT Industry. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Lyddon, Dave, Xuebing Cao, Quan Meng and Jun Lu. 2015. “A Strike of ‘Unorganised’ Workers in a Chinese Car Factory: The Nanhai Honda Events of 2010.” Industrial Relations Journal 46(2): 134-52.

Marketplace. 2012. “The People behind Your iPad.” April 12.

McKay, Steven C. 2006. Satanic Mills or Silicon Islands? The Politics of High-Tech Production in the Philippines. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

McNally, Christopher A. 2004. “Sichuan: Driving Capitalist Development Westward.” The China Quarterly 178:426-47.

Ministries of Education and Finance of the People’s Republic of China. 2007. “Zhongdeng zhiye xuexiao xuesheng shixi guanli banfa“ (Administrative Measures for Internships at Secondary Vocational Schools). [中華人民共和國教育部、財政部. 2007. “中等職業學校學生實習管理辦法”].

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 1996. “Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo zhiye jiaoyu fa“ (Vocational Education Law of the People’s Republic of China). [中華人民共和國教育部. 1996. “中華人民共和國職業教育法”].

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2010a. “Guojia zhongchangqi jiaoyu gaige he fazhan guihua gangyao (2010-2020)“ (Outline of China’s National Plan for Medium and Long-Term Education Reform and Development, 2010-2020). July 29. [中華人民共和國教育部. 2010a. “國家中長期教育改革和發展規劃綱要 (2010-2020年).” 7月29日].

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2010b. “Guanyu yingdui qiye jigonghuang jinyibu zuohao zhongdeng zhiye xuexiao xuesheng shixi gongzuo de tongzhi“ (The Circular on Further Improving the Work of Secondary Vocational School Student Internship Regarding Skilled Labor Shortage of Enterprises). March 10. [中華人民共和國教育部. 2010. “關於應對企業技工荒進一步做好中等職業學校學生實習工作的通知.” 3月10日].

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2012. “Zhiye xuexiao xuesheng dinggang shixi guanli guiding“ (Draft Rules on the Management of Vocational School Student Internships). November 15. [中華人民共和國教育部. 2012. “職業學校學生頂崗實習管理規定.” 11月15日].

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2014. “‘Zhongzhi xuesheng shixi guanli’ de guiding muqian shi nage?” (What are the Current Regulations on “The Management of Secondary Vocational School Student Internships”?). December 11. 中華人民共和國教育部. 2014. “‘Zhongzhi Xuesheng Shixi Guanli’ de Guiding Muqian shi Nage?“ (What are the Current Regulations on “The Management of Secondary Vocational School Student Internships”?) [中華人民共和國教育部. 2014. “中職學生實習管理”的規定目前是哪個? 12月11日].

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. 2014. “2013 Nian quanguo nongmingong jiance diaocha baogao“ (Investigative Report on the Monitoring of Chinese Rural Migrant Workers in 2013). May 12. [中華人民共和國國家統計局. 2014. “2013年全國農民工監測調查報告.” 5月12日].

Naughton, Barry. 2014. “China’s Economy: Complacency, Crisis & the Challenge of Reform.” Daedalus: Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences 143(2): 14-25.

Ngok, Kinglun. 2008. “The Changes of Chinese Labor Policy and Labor Legislation in the Context of Market Transition.” International Labor and Working-Class History 73:45-64.

Park, Albert, and Fang Cai. 2011. “The Informalization of the Chinese Labor Market.” In From Iron Rice Bowl to Informalization: Markets, Workers, and the State in a Changing China, edited by Sarosh Kuruvilla, Ching Kwan Lee, and Mary E. Gallagher, 17-35. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Perlin, Ross. 2011. Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy. London: Verso.

Pringle, Tim. 2011. Trade Unions in China: The Challenge of Labour Unrest. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Pun, Ngai, and Jenny Chan. 2012. “Global Capital, the State, and Chinese Workers: The Foxconn Experience.” Modern China 38:383-410.

Pun, Ngai, and Jenny Chan. 2013. “The Spatial Politics of Labor in China: Life, Labor, and a New Generation of Migrant Workers.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 112:179-90.

Pun, Ngai, Shen Yuan, Guo Yuhua, Lu Huilin, Jenny Chan, and Mark Selden. 2014. “Worker-Intellectual Unity: Trans-Border Sociological Intervention in Foxconn.” Current Sociology 62:209-22.

Ross, Andrew. 2004. Low Pay, High Profile: The Global Push for Fair Labor. New York: The New Press.

Ross, Andrew. 2006. Fast Boat to China: Corporate Flight and the Consequences of Free Trade-Lessons from Shanghai. New York: Pantheon Books.

Ruggie, John. 2013. Just Business: Multinational Corporations and Human Rights. New York: Norton.

Rural Education Action Program. 2014. “Apple and REAP Partnering to Protect Student Workers in China from Exploitation.” February 13.

SACOM (Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehavior). 2012. “Students and Scholars Demand Tim Cook Stop Using Student Workers and Ensure Decent Working Conditions at Apple Suppliers!” February 9.

Selden, Mark, and Elizabeth J. Perry. 2010. “Introduction: Reform, Conflict and Resistance in Contemporary China.” In Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, 3rd ed., edited by Elizabeth J. Perry and Mark Selden, 1-30. London: Routledge.

Sichuan Provincial People’s Government. 2011. “Sichuan: Top Choice of Taiwan Enterprises.” May 5.

Silver, Beverly J. 2003. Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization since 1870. Cambridge. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Chris, and Jenny Chan. 2015. “Working for Two Bosses: Student Interns as Constrained Labour in China.” Human Relations 68:305-26.

Smith, Ted, David A. Sonnenfeld, and David Naguib Pellow, eds. 2006. Challenging the Chip: Labor Rights and Environmental Justice in the Global Electronics Industry. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Solinger, Dorothy J. 2009. States’ Gains, Labor’s Losses: China, France, and Mexico Choose Global Liaisons, 1980-2000. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

The People’s Government of Guangyuan City (Sichuan). 2011a. “Shi Laodong he Shehui Baozhang Ju juzhang Li Zaiyang: Zai quanshi Fushikang Chengdu xiangmu renli ziyuan zhaomu gongzuo huiyi shang de fayan“ (Foxconn Chengdu Project Human Resources Recruitment Conference: Presentation by Li Zaiyang, Guangyuan Labor and Social Security Bureau Chief). January 25. [廣元市人民政府(四川). 2011a. “市勞動和社會保障局局長李在揚︰在全市富士康成都項目人力資源招募工作會議上的發言.” 1月25日.]

The People’s Government of Guangyuan City (Sichuan). 2011b. “Changwu fushizhang Zhao Yong: Zai quanshi Fushikang Chengdu xiangmu renli ziyuan zhaomu gongzuo Huiyi shang de jianghua“ (Foxconn Chengdu Project Human Resources Recruitment Conference: Speech by Zhao Yong, Deputy Mayor of Guangyuan City). January 25. [廣元市人民政府(四川). 2011b. “常務副市長趙勇︰在全市富士康成都項目人力資源招募工作會議上的講話.” 1月25日.]

Wang, Haiyan, Richard P. Appelbaum, Francesca Degiuli, and Nelson Lichtenstein. 2009. “China’s New Labor Contract Law: Is China Moving towards Increased Power for Workers?” Third World Quarterly 30:485-501.

Webster, Edward, Rob Lambert, and Andries Bezuidenhout. 2008. Grounding Globalization: Labour in the Age of Insecurity. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Weir, Bill. 2012. “A Trip to the iFactory.” ABC News, February 21.

Whyte, Martin King. 2014. “Soaring Income Gaps: China in Comparative Perspective.” Dædalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences 143:39-52.

Woronov, T. E. 2011. “Learning to Serve: Urban Youth, Vocational Schools and New Class Formations in China.” The China Journal 66:77-99.

Xinhua. 2015. “China’s Vocational Institutions Train 130 Million.” June 29.

Zhang, Lu. 2015. Inside China’s Automobile Factories: The Politics of Labor and Worker Resistance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zhengzhou City Education Bureau (Henan). 2010. “Guanyu dongyuan zhongdeng zhiye xuexiao xuesheng dao Shenzhen Fushikang Keji Jituan jiuye (shixi) de tongzhi“ (Notification to Mobilize Secondary Vocational School Students for Employment (Internship) at Foxconn Shenzhen). June 12. [鄭州市教育局(河南). 2010. “關於動員中等職業學校學生到深圳富士康科技集團就業(實習)的通知.” 6月12日.]

Zhou, Ying. 2013. “The State of Precarious Work in China.” American Behavioral Scientist 57:354-72.

Zipp, Daniel Y. and Marc Blecher. 2015. “Migrants and Mobilization: Sectoral Patterns in China, 2010-2013.” Global Labour Journal 6:116-26.

Notes

1 Concerning the rights protection of China-based student interns in transnational production, on 16 December 2013, we wrote letters to, respectively, Foxconn CEO Terry Gou and Apple CEO Tim Cook. Apple is the world’s most profitable technology company, which contracts Foxconn, among others, to manufacture its branded products. The two letters, and company statements, are on file with the authors.

2 On the inherent contradictions between legitimacy and profitability in global capitalism, and the varied responses of industrial capital and the state under specific historical context, see also Burawoy (1985), Silver (2003), and Webster et al. (2008).

3 The names of our interviewees, unless otherwise specified, are changed to protect them.

4 Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Wei Chengnianren Baohu Fa 2013) protects young people under 18 for their balanced development and healthy growth. Article 20 stipulates that schools, including vocational schools, shall “cooperate with the parents or other guardians of the minor students to guarantee the minor students time for sleeping, recreational activities and physical exercises and may not increase their burden of study.”

5 As of December 2013, in Shenzhen, Foxconn paid ten percent of employees’ basic monthly wage for social insurance (180 yuan) and five percent for the mandatory housing provident fund (90 yuan), that is, 270 yuan/month in total.

6 The Song of the Volga Boatmen (in Russian with Chinese illustration)

7 The Fair Labor Association (FLA) received from Apple membership dues of US$250,000, plus audit fees for conducting its investigation at Foxconn Chengdu and two other Foxconn factories in Shenzhen (Longhua and Guanlan) between 2011 and 2012 (Weir 2012). Given the complete financial dependence of the FLA on the companies that support it, we question its ability to fulfill its purported mission to protect workers in the global economy.

8 In 2010, at least 18 workers attempted suicide at Foxconn’s facilities in Shenzhen and other cities, resulting in 14 deaths and four crippling injuries, see Chan and Pun (2010) and Chan (2013).

9 It was estimated that in May 2010 approximately 70 percent of the 1,800 workers were student interns at a Honda parts plant based in Nanhai District in Foshan City, Guangdong. Following a significant victory in which Honda workers received an additional 500 yuan per month and underpaid interns over 600 yuan more per month, auto workers at supplier factories of Toyota and Hyundai were emboldened to take their demands to managers (see Butollo and ten Brink 2012; Chan and Hui 2014; Friedman 2014, chap. 5; Lyddon et al. 2015).