From a “Dysfunctional Japanese-Style Industrialized Society” to an “Ordinary Nation”?

Oguma Eiji with an introduction by David H. Slater

Oguma Eiji, a sociologist from Keio University, has emerged as one of the most astute commentators on the shifts that have occurred since the 3.11 crises. As an engaged intellectual with a respected history of solid scholarship, he has repeatedly done two things few others have: link the events since 3.11 to larger patterns of political and economic transformation in post-war Japan, and situate this moment in Japan in relation to similar moments of political crisis beyond Japan.

Perhaps best known to English-speaking audiences is his volume on A Genealogy of Japanese Self-Images(Trans-Pacific Press) 単一民族神話の起源―「日本人」の自画像の系譜 (新曜社). Relevant here is also his two volume study of youth revolt. 1968: 叛乱の終焉とその遺産 (新曜社). Both of these works provide useful background to the events since 3.11, but especially to the broad shifts that led up to this moment.

On April 22-23, 2012, Oguma spoke at Berkeley’s Institute of East Asian Studies conference, Towards Long-term Sustainability: In Response to the 3/11 Earthquake and the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. His talk was translated by Beth Cary under the title, “Historical Background of the Fukushima Accident and the Anti-nuclear Movement in Japan.” Both English and Japanese papers, as well as those by other participants can be downloaded here under Abstracts.

While much of the mainstream press has focused on the immediate causes of nuclear disaster (miscalculation in design, negligence of maintenance, vacuum of political leadership, etc.), Oguma shows how the rise of the nuclear industry is linked to much longer-term shifts—the shifts in industrialized society that ushered in a glut of construction and energy expansion as supported by the convergence of corporate, bureaucratic and political interest, a shift he sums up as the “Japan as Number One” syndrome of the postwar decades. Oguma explains that this was followed by a lapse into a “post-industrial society” that saw the population and energy use fall, along with the burst of the bubble and the decline in Japan’s national economic trajectory, which led to the unraveling of these vested interests. Within this familiar narrative, Oguma shows how strong governmental backing of the nuclear industry, linked to the monopoly by electric utility companies as providers of consumer energy, gave rise to a structural conflict of interest that prevented robust safety regulation.

The choice to locate nuclear power plants in depopulated rural areas from the 1950s forward was strategic. It benefited from cheap local labor, and while the wages were often exploitative, these jobs were still valued in the face of a regional labor shortage. Government subsidies to deficit-ridden communities could buy local support and quell opposition. Economic decline, labor shift and demographic shrinkage, brought what Oguma calls “’Japanese Style Industrialized Society’ in Dysfunctional Mode” in a period when the LDP could no longer secure the same degree of support among rural populations and small and medium sized businesses everywhere.

Perhaps especially interesting in light of the past year’s events are his comments on the deterioration of support among women (Compare David H. Slater, “Fukushima women against nuclear power: finding a voice from Tohoku“). As regular employment deteriorated, men’s allegiance to the firm fell away, more women were working outside the home, and younger irregular workers found some common cause with older anti-nuclear activists in ways that allowed new forms of political involvement. Oguma lays out the links between economy and labor, gender and demographics that, he argues, provided a new social, and class terrain, for the rise of social movements of today. (See also Hasegawa Koichi’s essay in the same excellent collection of Berkeley conference papers.)

In a series of editorials in the Asahi, Oguma addressed readers more directly. On March 9, 2012, he exhorted his readers to “think for themselves” in deciding whether nuclear power is appropriate for Japan, pointing out the importance of an informed citizenry and the possibility of protest as a viable and even necessary tool of social change, albeit, one that requires more of each individual than they are used to giving. On May 9, 2012, he points to the impossibly high economic and social costs required to somehow minimize or even manage the risk that nuclear power poses to society and humanity. Oguma points to the need for “courage” in facing up to entrenched interests of banks and insurance companies, corporations and bureaucrats, in a Japanese state that is still authoritarian, even in dysfunction.

|

|

In the interview below, Oguma sums up the convergences of what he sees as providing the conditions for political engagement: lack of expectation or faith in politics in general has turned into a lack of faith that politicians are able or even interested in providing the sorts of leadership that is required to pull Japan out of prolonged recession. Since 3.11, we have seen this disillusionment compounded by the lack of confidence in politicians’ motives and ability to respond effectively to a national crisis. Be it incompetent mismanagement of economic recovery, or intentional, even duplicitous revealing of selective pieces of information regarding energy policy and danger, the bureaucrats and politicians have revealed themselves to no longer be worthy of the implicit trust that the Japanese people have given them for much of the postwar period. Along with industrial high growth, middle-class membership and income doubling plans, the period of assumed political faith is gone, never to return, and, Oguma points out, those in power have yet to notice this. But those in the street have noticed. This is an important frame for understanding what is going on today in the streets and through Twitter.

In one of the most salutary moments, Oguma’s reminds us that the Japanese protests of the 1960’s Security Treaty, the largest of the postwar era, lasted only about a month. Indeed, even the May 1968 Paris protests lasted less than two months. Since 3.11, in the face of a series of autonomous popular protests (that is, protests that are not dependent upon the institutional structure of corporate unions or political parties) have lasted almost a year, going back to September 2011. To Oguma, this is evidence that we are witnessing a transformation away from indifference or hopelessness to engagement and investment.

With what he called the ‘Ancien Régime’, (complete with scattered references to the chaotic attempts to preserve aristocratic privilege) or the ‘political-bureaucratic-business complex’ (with echoes of the “military-industrial complex”?), two images that point to the possibility of overthrow through popular resistance, Oguma resituates these post 3.11 events beyond Japan, thereby providing an important point of reference but also perhaps the start of a template of action for what he calls new social movements.

Oguma’s argument that Japan is becoming an “ordinary nation” comes from the observation that any other nation, facing these sorts of crises— of economic stagnation, political indifference, and now crisis mismanagement— would lose faith, trust, and be forced to act. In fact, he points out that it would be a “weirder situation” if the Japanese people retained faith in politics as usual in the face of crisis. DHS

The following interview with Oguma Eiji appeared in the Asahi Shimbun on July 19, 2012.

In a country long considered lacking a culture of protest, thousands of people are gathering every Friday night in Tokyo’s Nagatacho political district to protest nuclear energy and the government’s decision to restart reactors.

|

|

Question: It had been said that people just do not demonstrate in Japan. Now, however, a large number of people are participating. What did you notice about the demonstrations being held near the Prime Minister’s Official Residence?

Oguma: While there are young people, senior citizens and couples with their children, there are also many in their 30s and 40s who happen to be men not wearing suits and women without children.

About a decade or so ago, that would have been the age bracket that would be least likely to take part in demonstrations because they would be either working at a company or busy taking care of their children.

I believe the shift is a reflection of structural changes in industry and society that has seen an increase in those working in non-regular jobs as well as a greater tendency to have fewer children and marry later in life.

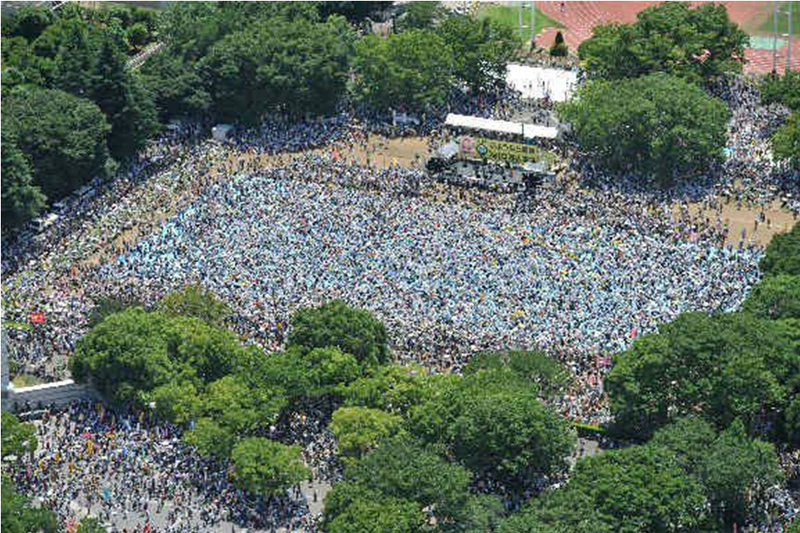

Q:Protest organizers have said that more than 100,000 people are attending each protest.Why do you think that is so?

A:With dissatisfaction and distrust of politicians having accumulated over 20 years of economic stagnation, the distrust of government reached criticality after the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant and the decision to resume operations at the Oi nuclear power plant in Fukui Prefecture.

If nothing had happened even after such developments, that would have been an even weirder situation. That is accepted wisdom in the international community.

Foreigners who looked like they worked at foreign embassies as well as foreign media came to observe the demonstrations. It would be no surprise if they saw the confrontation as one between “an Asian democracy movement” and “an insensitive authoritarian state.”

The reason such a large demonstration did not occur over the past few decades is because, on the one hand, people had never seen or taken part in demonstrations and because, on the other hand, people’s lives and jobs were stable.

Even today, the least sensitive are those with stable jobs and college students. Looking at the types of people who are organizing the latest protests, they are a 25-year-old providing care to the elderly and a 31-year-old who works in interior decoration. Because they feel something through the course of their daily lives, they likely believe they cannot allow the political and business worlds to continue acting in the way they have.

Q: What are the differences in the mood with the period in 1968, when student protests were much more prominent?

A: The 1960 protests against the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty were centered on organized labor and college students. In 1968, it was fundamentally only college students. That was a time when college students were the only ones with free time, outside of those mobilized by organizations.

Now, however, there has been a large increase in those with more freedom to act because of the nature of their jobs and working hours. Of course, that freedom also has the double meaning pointed out by Karl Marx, that people who have such freedom also have the freedom to die from starvation.

The Security Treaty protest was settled after the government came out with an income-doubling plan. In 1968, the economy was still expanding so the protests ended after the students found jobs in companies.

Now, the government cannot come up with an income-doubling plan, and those at the center of the demonstrations are not college students who would leave once they graduated.

It will not be easy to overcome the structural dissatisfaction and political distrust.

Q: What do you feel is pushing people to take part in the demonstrations?

A: There is, of course, the nuclear accident and fears about radiation.Anger is also intense because the people feel that politicians are ignoring them.

Some people may feel, “It was enjoyable once I tried it.” With so many people of similar opinions gathering together, there is also an attraction in being able to meet with acquaintances for the first time in a while or to shake hands with total strangers.

Q: What do you think “nuclear power” and “resumption of operations” represent for the protesters?

A: In the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in the United States, many protesters had high educational backgrounds but were working in non-regular jobs. When they thought about who was responsible for putting them in the position they were in, their anger became directed at Wall Street and Washington, or, in other words, the financial elite and government.

In Egypt, there were many young people with high educational backgrounds and with Facebook skills, but with no jobs. Their anger was directed at the Hosni Mubarak regime.

What was it in Japan? It was not the prime minister, nor those who lived and worked in the Roppongi Hills area.

With the nuclear accident, it became increasingly clear there was a political-bureaucratic-business complex in play.People looked at those in the complex as making decisions while ignoring the general public, as not having any intention to protect the public’s safety and as having gained vested interests through their insider status.

I believe behind the protests against resuming the Oi plant operations are a protest against the entire current state of Japan.

Q: What do you think about the comment attributed to Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko, who complained the protesters were making a loud racket?

A: I recalled the diary of Louis XVI during the French Revolution. On the day a mob attacked the Bastille, the king wrote in his diary that nothing happened. Because he went hunting almost daily, the entry meant that he didn’t catch anything. There was no recognition that society was being shaken from its very roots.

When politicians and reporters in the political news sections of major newspapers work in a sort of village society, they are unaware of what is occurring in the outside world. They begin to feel that an issue cannot be a major problem as long as it does not affect that village society. Or they may look at everything through the filter of that village society by, for example, saying something was instigated by those close to Ozawa Ichiro or someone else.

That form of politics and political reporting is a characteristic of what has transpired since the 1970s.

Q: What is the difference with what occurred before that period?

A: Before 1970, if there was a major demonstration in front of the Diet, there would have been a response that it represented a “communist threat” or “a crisis of the state.”

However, from about the mid-1970s, when the political world became much more stable, it became possible to understand all about politics by simply pursuing faction leaders of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. That was because the social system was almost like the one in which approval of the faction leader meant that the LDP, the Diet, the local assembly members and even the neighborhood associations and labor unions further below would also give their approval.

Although only men were active members of all those groups, everyone felt that women would vote according to what their husbands told them to do.

That social structure has completely changed. Under that old system, only about 30 percent of the population would be covered. Methods used in the past no longer apply with more than half of the population having no party loyalty.

Those in the higher ranks of the ancient regime, namely the political-bureaucratic-business complex and major media organizations, are the ones who least understand that change.

Q: Why have politicians and political parties lost the trust of the people?

A: It is because the social system that was built up since the end of World War II has reached its limits.

That system was led by the manufacturing and exporting sector, with regular male company employees providing for their families through stable jobs and the central government handing out subsidies and public works projects to local governments.

While some people may hold nostalgia for such a framework, there is no way of going back to such a system.

Between 1998 and 2008, the public works project budget was cut in half due to fiscal problems. The large number of municipal mergers in the Heisei Era (1989-present) led to a major decrease in the number of local assembly members.

A simple way of explaining why the LDP government was toppled is because it could no longer distribute money. Although the Democratic Party of Japan took over, nothing changed.

Q: Is it possible that the framework for representative democracy no longer matches the needs of the times?

A: That is possible.

But looking at the process by which Oi plant operations were resumed, I believe there are other issues. I never thought the government would bungle things so badly. I can only think that it has lost all ability to deal with reality.

It would have been a different matter if the government had publicized everything about the actual situation and then presented a specific timeline for moving away from nuclear energy, deciding which reactors would be decommissioned and allowing only those that passed strict appraisals to resume operations.

However, not even that was possible due to resistance from some business sectors. That led to increased distrust of the overall system.

A favorable interpretation of the decision to resume operations might have the following logic: Unless restarts were carried out, electric power companies would record losses one after another and a financial depression might be triggered if banks could not collect on loans made to electric power companies.

However, we do not know if the entire Japanese economy would fall into a crisis. The matter might be resolved if Tokyo Electric Power Co. and the banks took responsibility for management and investment mistakes. At the very least, the argument about an electricity shortage is not convincing because there is sufficient electricity in all of Japan by having only two nuclear reactors of Kansai Electric Power Co. in operation.

It is the government itself that has brought about the crisis in the representative system.

There is the sense that those taking part in the demonstrations no longer want lawmakers to represent them.

Did people expect anything from Louis XVI?

There are many people who feel about lawmakers, “If you want to come here, you should come on your own.”

Q: Is it not dangerous to have a situation in which various social organizations and frameworks have lost the people’s trust?

A: It is true that there has been a loss of stability.

Whether that represents a dangerous situation or an opportunity for change will depend on the response that is made.

But, I believe that change is inevitable.

There is no way of returning to a society in which everyone is a member of the middle class. But I do not believe there is anyone who knows in what way society will change.

Q: Many people feel there is no political party they can vote for. In what direction will unaffiliated voters move?

A: The term unaffiliated voter can only be used in relation to party support.

The bureaucracy has also lost trust.

People are beginning to feel that member companies of Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) are only concerned about profits for their own companies.

Media organizations have become insensitive to an extent that people are beginning to suspect some form of censorship. That is why more people are turning to the Internet.

When jobs, families and politics become unstable and traditional parties are unable to gain votes, a common phenomenon found in advanced nations is for populists to garner support. At the same time, another common trend is for new forces to gain support, such as the Greens in Germany.

Q: What is the new trend that may now be emerging in Japan?

A: I am focusing on how this new movement will evolve.

Since April 2011, I have participated in some form of demonstration on several occasions every month. While the organizers and locations have changed, it has continued much longer than I expected and it has gone beyond a temporary boom.

In the 1960 Security Treaty protest, the height of activity only lasted for about a month. The May 1968 revolution in Paris only lasted about two months. A boom would not last for more than six months. Even if the situation in front of the Prime Minister’s Official Residence should be settled, I think other protests will take place somewhere else.

Q:But aren’t politicians taking these protests lightly?

A: That is what is making the crisis more serious.

If one person decides to join a free participation demonstration, there are likely 100 people in the background. Politicians would have to think about the meaning of having 100,000 people gather in Tokyo alone.

Since 3/11, the political literacy of the public has increased substantially.

It is a good thing for democracy to become a society in which demonstrations are possible and if there are more people who hold the sense that they can participate in politics.

While one example of trying to suppress such a movement by force occurred in China in 1989, the economy continued to grow there.

If a similar attempt to suppress by force was made in Japan, dissatisfaction would emerge elsewhere in a different form.

Q: Are you saying we have entered a new era?

A: I believe so.

The first postwar era was the period of confusion after World War II that lasted until 1955.

The second postwar era was until 1991, when the Cold War ended. That was an era of economic growth.

The third postwar era that followed was one of being unable to retreat from a framework that had been constructed during the era of high economic growth and trying to forcibly maintain it by distributing more money. I believe we have reached the limits of that last era.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Japan was unique because with the economy strong, jobs stable, and social movements stagnant, the political world could afford to be a third-rate one in which the only concern was factional struggle. That was a time when Japan was considered a strange place.

Now, all those factors no longer exist. Unemployment has increased, economic disparity has widened and social movements have emerged.

I believe Japan will move toward becoming a more ordinary nation.

But will it be able to continue with a third-rate political sector?

Q: For the sector of the population with more free time, the most important value is no longer money. I feel a change. Can that be considered hope?

A: Over the past year or so, I have met many people who are engaged in various new activities. I am amazed at what they do. While they are competent and intelligent, their lives are unstable because their income levels are low. Despite that, there are many who continue to be active in providing support to disaster victims or protesting the government.

I believe they are the salt of the earth.

I believe a society that cannot adequately take advantage of the voices and abilities of such people is not a good one.

(The interview was conducted by Kazuaki Hagi.)

Oguma Eiji is professor of Policy Management, Keio University and an historical sociologist. His book, A Genealogy of ‘Japanese’ Self-Imagesis a translation of Tan’itsu minzoku shinwa no kigen (The origin of the myth of Japanese as a homogeneous ethnic group), which won the Suntory Culture Award. He is coeditor with Kang Sangjung of Zainichi issei no kioku (Memories of the First Generation of Koreans in Japan) 在日一世の記憶 / 小熊英二, 姜尚中編.

David H. Slater is an Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Sophia University, Tokyo, whose work involves youth culture, social class and urban space. He is the co-editor with Ishida Hiroshi of Social Class in Contemporary Japan: Structures, Sorting and Strategies. Since 3/11, he has been doing the ethnography of disaster and relief in Tohoku, and was the Guest Editor of Hot Spots: 3.11 Politics in Disaster Japan: Fear and Anger, Possibility and Hope, in Cultural Anthropology (2010) <link>

Recommended citation: Oguma Eiji with an introduction by David H. Slater, “From a Dysfunctional Japanese-Style Industrialized Society to an ‘Ordinary Nation’?,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 31, No. 2, July 30, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

•David H. Slater, Nishimura Keiko, and Love Kindstrand, Social Media, Information and Political Activism in Japan’s 3.11 Crisis

•Asia-Pacific Journal Feature, Eco-Model City Kitakyushu and Japan’s Disposal of Radioactive Tsunami Debris

•Makiko SEGAWA, After The Media Has Gone: Fukushima, Suicide and the Legacy of 3.11

•Yuki Tanaka, A Lesson from the Fukushima Nuclear Accident

•Jennifer Robertson, From Uniqlo to NGOs: The Problematic “Culture of Giving” in Inter-Disaster Japan

*Iwata Wataru interviewed by Nadine and Thierry Ribault, Fukushima: “Everything has to be done again for us to stay in the contaminated areas”

•Koide Hiroaki, Japan’s Nightmare Fight Against Radiation in the Wake of the 3.11 Meltdown

•Jeff Kingston, Mismanaging Risk and the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis

•Maeda Arata and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Amid Invisible Terror: The Righteous Anger of A Fukushima Farmer Poet

•Timothy S. George, Fukushima in Light of Minamata

•David McNeill, The Fukushima Nuclear Crisis and the Fight for Compensation

•David Slater, Fukushima women against nuclear power: finding a voice from Tohoku

•Koide Hiroaki and Paul Jobin, Nuclear Irresponsibility: Koide Hiroaki Interviewed by Le Monde

•Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Fukushima and Okinawa – the “Abandoned People” and Civic Empowerment

•Nicola Liscutin, Indignez-vous! ‘Fukushima,’ New Media and Anti-Nucler Activism in Japan

• Chris Busby, Norimatsu Satoko and Narusawa Muneo, Fukushima is Worse than Chernobyl – on Global Contamination

• Robert Jacobs, Social Fallout: Marginalization After the Fukushima Nuclear Meltdown

• Say-Peace Project and Norimatsu Satoko, Protecting Children Against Radiation: Japanese Citizens Take Radiation Protection into Their Own Hands

• Matthew Penney and Mark Selden, What Price the Fukushima Meltdown? Comparing Chernobyl and Fukushima

• Hirose Takashi, The Nuclear Disaster That Could Destroy Japan – On the danger of a killer earthquake in the Japanese archipelago

• Paul Jobin, Dying for TEPCO? Fukushima’s Nuclear Contract Workers

• Andrew DeWit and Sven Saaler, Political and Policy Repercussions of Japan’s Nuclear and Natural Disasters in Germany

• Makiko SEGAWA, Fukushima Residents Seek Answers Amid Mixed Signals From Media, TEPCO and Government. Report from the radiation exclusion zone

• Kaneko Masaru, The Plan to Rebuild Japan: When You Can’t Go Back, You Move Forward. Outline of an Environmental Sound Energy Policy