Abstract: Hong Kong made it through the first half of 2020 relatively unscathed by Covid-19, largely due to a first-class public-health response strongly supported by the city’s population. The impact of the disease on its economy will be severe, but society, prepared psychologically and practically by its encounter with SARS in 2003, will survive the outbreak with little trauma. Politically, the outbreak has been turned to advantage by the government to dampen the city’s anti-government protests. As a result of its smart handling of Covid-19, the disease will not be Hong Kong’s big event of 2020; rather it will be relegated to very much second place, far behind the Chinese government’s imposition of a National Security Law.

Introduction

Hong Kong has been one of the most successful societies in the world in coping with Covid-19. The reasons for this are easy to identify — above all tracking and tracing and closing its border which in turn allowed it to get by with light social distancing measures and no lockdown.

The impact of Covid-19 on Hong Kong, however, will be significant. Immediately, its economy is heading for a major downturn, and the disease could end up badly affecting two of what the government likes to call the four pillars of its economy. It is also having a say in shaping politics in Hong Kong. Where it has had less of an impact so far is on society, which in many ways seems to have come through the last few months relatively unscathed. Yet at the same time, from the eruption of mass opposition to the government last year to the imposition of a national security law on the city on 1 July, 2020 Hong Kong has gone through its biggest transition at least since Britain returned it to full Chinese control in 1997 and probably since the unrest of the 1960s which led to profound changes in the nature of the social contract between its rulers and its people.

In this paper, I consider first how Hong Kong managed its brush with Covid-19, then the nature of the disease’s impact on three areas of the city’s life — its economy, society and politics — before concluding with a brief discussion of its impact on a society undergoing a traumatic transition from being open and liberal to authoritarian control.

The Numbers

Hong Kong recorded its first Covid-19 case on 23 January. As of June 30, it had recorded 1,206 case and seven deaths. Of the total cases, almost two-thirds were imported — discovered through testing at the border. Local cases, including ones identified as possibly local or epidemiologically linked with local or possibly local cases, totaled 411, or 34 percent (see table).

| Table 1: Hong Kong’s Covid-19 cases to 30 June 2020 |

| Number | Share of total, % | |

| Imported | 766 | 64 |

| Epidemiologically linked with imported case | 27 | 2 |

| Local | 68 | 6 |

| Possibly local | 103 | 9 |

| Epidemiologically linked with local case | 178 | 15 |

| Epidemiologically linked with possibly local case | 62 | 5 |

| Total | 1,206 | 100 |

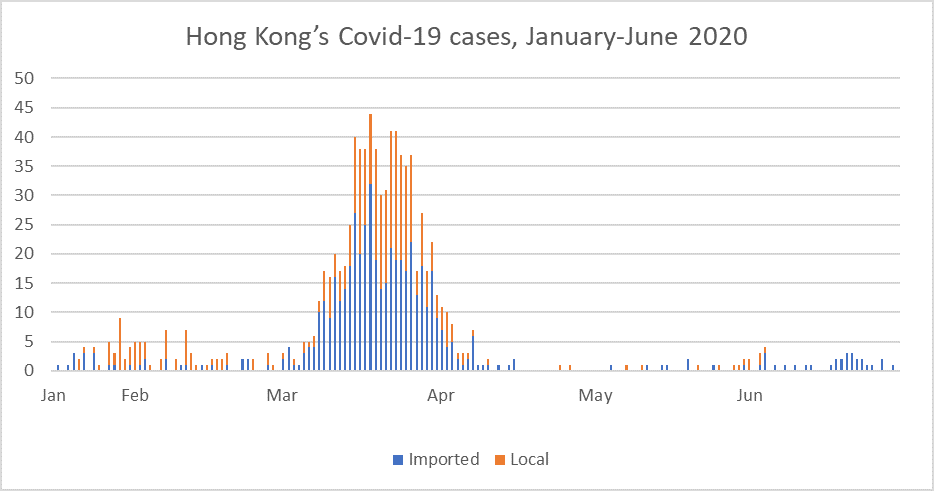

As the chart below shows, the vast majority of Hong Kong’s Covid-19 cases occurred in the month between 9 March and 8 April. From 1 May to 30 June, it only recorded two local cases and 13 epidemiologically local cases. That period also saw it record 146 imported cases — all residents of Hong Kong found to be infected with the virus on their return to the city from elsewhere in the world.

|

Source: Centre for Health Protection (2020) Note: Chart excludes asymptomatic cases. Imported cases include cases epidemiologically linked with imported cases, and local cases include possibly local cases, cases epidemiologically linked with local cases and cases epidemiologically linked with possibly local cases. |

Hong Kong’s Coronavirus Timeline

|

23 January |

First Covid-19 case confirmed |

|

25 January |

State of emergency declared |

|

27 January |

Residents of Hubei province and mainland citizens who had visited Hubei in the previous 14 days barred from entry |

|

All Hong Kong residents who visited Hubei province in previous 14 days quarantined |

|

|

Flights to/from Wuhan suspended |

|

|

30 January |

Six border points closed |

|

Flights to mainland China reduced |

|

|

Cross-border bus services reduced |

|

|

All schools closed |

|

|

3 February |

6,000 healthcare workers start five-day strike calling for the closure of the border with the rest of China |

|

4 February |

Four more border points closed. Only two remain open. |

|

7 February |

Healthcare workers vote against extending their strike for a second week |

|

8 February |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all arrivals from mainland China |

|

25 February |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all visitors from South Korea |

|

1 March |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all visitors from Iran and parts of Italy |

|

14 March |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all visitors from rest of Italy and parts of France, Germany, Japan and Spain |

|

17 March |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all visitors from Schengen area of EU |

|

20 March |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all visitors from all overseas countries and territories |

|

24 March |

14-day mandatory quarantine for all visitors from Macau and Taiwan |

|

26 March |

All non-Hong Kong residents barred from entering |

|

29 March |

Gatherings of more than four people in public places barred |

|

7 May |

Limit on public gatherings raised from four people to eight people |

|

18 June |

Limit on public gatherings raised from eight people to 50 people |

|

Source: (Cowling et al 2020, e282), author research |

Reasons for Hong Kong’s Successful Response

Hong Kong’s success in containing Covid-19 can be attributed to the city learning lessons from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2003, which killed 299 people in the city – more than anywhere else worldwide, apart from China.

At the heart of Hong Kong’s response was its Centre for Health Protection, a body set up in the aftermath of the SARS crisis charged with responsibility for disease prevention and control. For its day-to day-operations, the centre is guided by its “3Rs”, real-time surveillance, rapid intervention and responsive risk communication, all of which were brought into play in its response to Covid-19.

The centre coordinated Hong Kong’s response to Covid-19, organising its public health network to identify and manage any cases of the disease found in Hong Kong. The centre set up quarantine facilities, prepared hospitals to handle infected patients, put in place a testing regime, notably at Hong Kong International Airport where it has been able to test every arrival since 19 March, and has provided up-to-date information on a daily basis via its website.

Guided by the centre, two measures have proved particularly important in securing Hong Kong’s success in containing Covid-19. First, the rapid introduction of border controls, with the closure of six land and sea ports within seven days of the first Covid-19 case being confirmed in Hong Kong, and almost all of the rest within a week. And second, putting in place an elaborate testing and tracing system involving the locating and quarantining of close contacts of anyone found to be infected. From 8 February onwards – 15 days after the first Covid-19 case – all arrivals from mainland China were required to undergo a 14-day quarantine (in their own homes, in the case of Hong Kong residents; in government-designated facilities for visitors).

A five-day strike by public health-care workers, from 5-7 February, was also important in pushing the government to close all but two borders with the rest of China. By the time of the strike, however, schools had already been closed for more than a week and civil servants were already working from home.

The government subsequently closed playgrounds and leisure venues, and imposed social distancing measures, banning public gatherings of more than four people and requiring restaurants to keep a gap of 1.5 metres between tables in restaurants. Community level efforts also probably had some impact in keeping infection rates low via the near-universal wearing of surgical masks, the washing of hands and use of hand sanitizer, and the deployment of thermal scanners in offices, shopping plazas and many shops and restaurants.

The very fact that Hong Kong never had to undergo a full lockdown points to the success of the first two measures in lessening the need for the kind of restrictions imposed in many other countries.

|

Temporary partitions aimed at impeding the spread of Covid-19 installed in a Hong Kong café. Photograph: Simon Cartledge |

Impact on the Economy

Covid-19 had an enormous impact on Hong Kong’s economy in the first half of 2020. First quarter data showed a year-on-year contraction in gross domestic product (GDP) of 8.9 percent, the biggest quarterly drop ever recorded. The second quarter also looks certain to show a contraction.

In May, Paul Chan, the government’s financial secretary, said he expected GDP for the year as a whole to fall between -4 percent and -7 percent, sharply down from the forecast he had made during his budget speech of late February of growth of between -1.5 percent and 0.5 percent.

Covid-19 brought Hong Kong’s tourism industry — already badly hit by the protests that began in June 2019 — to a complete halt. Visitor arrivals from being down “just” over 50 percent in January compared with the same month a year earlier, have fallen to almost zero since Hong Kong closed its border to non-residents on 25 March.

It has also badly hit Hong Kong’s trade and logistics sector, the city’s biggest employer, accounting for around 720,000 jobs in 2018, with the Hong Kong Trade Development Council (HKTDC) announcing in mid-June that it was revising its export forecast for 2020 from a fall of 2 percent to a fall of 10 percent due to the impact of Covid-19 and trade protectionism (HKTDC 2020).

Less directly affected has been its second biggest sector, financial services. For example, JD.com, one of China’s leading online shopping companies, in early June raised US$3.9 billion with a secondary listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

The unemployment rate in Hong Kong has more than doubled since September 2019, when it stood at 2.9 percent, to 5.9 percent (230,400 people) as of March-May 2020.

May saw 2,079 bankruptcy filings, the highest monthly figure since SARS in 2003 (though that number may have been artificially inflated due to court closures in the previous two months that made almost all filings impossible).

As of mid-2020, it appears likely that Hong Kong will emerge from the coronavirus pandemic more reliant on financial services than it was before the crisis. While its trade and logistics sector remains a core part of the city’s economy, its overall importance to Hong Kong has been in long-term decline since 2005, with its share of GDP falling from around 30 percent then to around 20 percent now. This decline is largely due to mainland China taking over work previously done in Hong Kong, in addition to certain types of manufacturing having migrated to Southeast and South Asia. The adoption of new forms of digital technology in the management of supply chains also has had an impact. The coronavirus pandemic almost certainly led to some companies shrinking or reworking their sourcing and supply chain operations in Hong Kong and adopting new technologies such as video conferencing that mean they will have less need either for trade-related services provided in Hong Kong or to make visits to the city.

Its tourism industry will make some kind of recovery. However, it looks likely that it will not be as important as before as it appears to have permanently lost some attraction to its biggest market, visitors from other parts of China.

Impact on Society

So far, Hong Kong appears to have remained relatively unscarred by Covid-19. Aside from the fact that the number of people catching the disease has been small, and those dying of it as a result of catching it in Hong Kong, has been tiny, the most plausible explanations for this are first that the city’s experience with SARS in 2003 prepared it for the impact of another coronavirus, psychologically as well as practically, and second that the city never went into a full lockdown, allowing people to maintain some sense of normalcy in many parts of their life.

Overall, there was a broad consensus on what actions made sense. Within a few days of the first confirmed case, mask wearing in public was ubiquitous and has remained that way until now, despite the near total absence of local cases. In Hong Kong, among the local population, there is no stigma to wearing a mask in public. It was noticeable, though, even to the most casual of observers, that European and American expatriates, especially males, took significantly longer to embrace the mask-wearing habit. On 16 March, Apple Daily, a popular (pro-democracy) newspaper, featured a front-page picture of a group of expatriates socialising outside a bar under the headline “Westerners freely walking around without wearing masks” (Apple Daily 2020).

|

Poster opposing the establishment of a Covid-19 clinic in Hong Kong island’s Shau Kei Wan district. Photograph: Simon Cartledge |

As noted above, while all public facilities were shut by the government, and a number of private ones, including gyms, bars, beauty salons, massage parlours and tattoo businesses were also later required to close, many others including most retail shops, supermarkets and wet markets, remained open, as did restaurants (adhering to social distancing rules).

Working practices followed a similar split. Government staff were asked to work from home from 28 January onwards, returning to their offices from 2-20 March, then working from home again until early May, since when most public services have resumed and facilities re-opened. Private businesses adopted a mixture of work patterns, ranging from working from home to dividing staff into shifts working different days or weeks.

Throughout the last five months, the Hong Kong Jockey Club, the monopoly provider of gambling services in Hong Kong, has continued to run its twice weekly horse racing events. No audience is allowed in to its two race tracks during events and the club has closed all of its 101 off-course betting centres, but people can continue to bet through its on-line services.

The Impact on Politics

Covid-19 arrived at an opportune time for the Hong Kong government, giving it an additional tool for banning mass gatherings and so playing an important role in reducing the number and turnout at anti-government protests in the last five months.

Since late January, the Hong Kong Police Force, citing coronavirus restrictions, has not given permission for any marches or rallies. When protests have occurred, attendance has been low compared with similar events last year.

Covid-19 has also given the police another tool to discourage people from attending protests. From 21 April onwards, police began to issue people at protest sites with tickets fining them HK$2,000 (US$256) tickets for violating coronavirus rules barring public gatherings of more than four people. By 17 June, more than 700 of these tickets had been issued, a majority of them apparently at or near protests (HKFP 2020).

The one exception to this pattern of banning protests and then arresting or fining attendees was the gathering held on 4 June to mark the 31st anniversary of China’s suppression of the 1989 student-led democracy movement in Beijing. Despite having declared the gathering illegal, police did nothing to prevent several thousand people from entering the site of the vigil, Victoria Park on Hong Kong island, and remaining there for the next hour or so, before departing peacefully. One week later, however, several leaders of the event were charged with inciting others to join an illegal assembly (RTHK 2020).

|

Protesters maintaining social distancing at the candle-lit vigil held in Hong Kong island’s Victoria Park on 4 June 2020. Photograph: Simon Cartledge |

The failure of the government to shut Hong Kong’s borders with the rest of China as rapidly as the public demanded allowed the opposition to claim that it was more responsive to the needs of the people in Hong Kong than its leaders. The initial reluctance on the part of Chief Executive Carrie Lam to advocate a universal wearing of face masks contributed to this perception.

While there has been a small fall in popular opposition to the government during the Covid-19 outbreak, Hong Kong’s successful handling of Covid-19 has not brought its leaders any significant gain in support. An opinion poll conducted for Reuters by the Hong Kong Public Research Institute in June 2020 found that the resignation of Lam was still supported by 57 percent of those polled versus 63 percent three months earlier. Hong Kong’s current state of affairs was primarily blamed on its government (39 percent, versus 43 percent three months earlier), followed by the central government in Beijing and the pro-democracy camp (both 18 percent up from 14 percent), and then the police (7 percent, down from 10 percent) (Reuters 2020).

Conclusion

Although Covid-19 has and will continue to have a big effect on Hong Kong, its impact has been muted thanks to the measures taken by the government, especially its public health officials, and a population prepared to take rapid action to protect themselves arising from their experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Probably the greatest long-term impact will be economic as business conditions in Hong Kong and in many of the places it conducts business with continue to worsen through the second half of 2020 and into 2021. Possibly, if companies rework their international supply chains as a result of the disease, it could lessen the city’s importance as a trade and logistics centre. However, the fact that Hong Kong never underwent a full lockdown, with people continuing to work, also points to the city being able to negotiate the pandemic without the same kind of drastic fall in economic output seen elsewhere.

The city’s response to the disease offers valuable lessons to public health officials and governments around the world, notably the importance of border restrictions, isolation of infected people and quarantine of their close contacts.

But the irony of Hong Kong’s enormously successful response to Covid-19 is that it has made the coronavirus pandemic a sideshow for the city. Instead other events — notably, the stepped up involvement of Beijing in the running of Hong Kong, culminating in the imposition by Beijing of a National Security Law which came into effect on 1 July — have been of far greater importance, leaving the disease as a backdrop against which this momentous event played out.

Sources

Apple Daily, “西人無罩自由行”, page A1, 16 March 2020.

Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, “Latest situation of cases of COVID-19 (as of 30 June 2020)”, 30 June 2020, available at “Archives of Latest situation of cases of COVID-19” (accessed 1 July 2019).

Benjamin J Cowling, Sheikh Taslim Ali, Tiffany W Y Ng, Tim K Tsang, Julian C M Li, Min Whui Fong, Qiuyan Liao, Mike YW Kwan, So Lun Lee, Susan S Chiu, Joseph T Wu, Peng Wu and Gabriel M Leung, “Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study”, Lancet Public Health 2020; 5: e279–88, 17 April 2020. (accessed 1 Jul 2020).

HKFP (Hong Kong Free Press), “Coronavirus: Hong Kong police issue 705 fixed penalties for congregating, totalling HK$1.41m”, 17 June 2020, (accessed 1 July 2020).

HKTDC (Hong Kong Trade Development Council), “2020 Mid-Year Export Review: Pandemic and Protectionism Combine to Trigger Double-Digit Decline”, 16 June 2020.

RTHK (Radio Television Hong Kong), “Lee Cheuk-yan and others charged over June 4 vigil”, 11 June 2020 (accessed 1 July 2020).

Reuters, “Exclusive: Support dips for Hong Kong democracy protests as national security law looms – poll”, 26 June 2020, (accessed 1 July 2020).