|

2018 Kyoko Selden Translation Prize Announcement On the fifth anniversary of the establishment of the Kyoko Selden Memorial Translation Prize through the generosity of her colleagues, students, and friends, the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University is pleased to announce the winners of the 2018 Prize. “Honorable Mention in the category of “Already Published Translator” has been awarded to Bruce Allen, Faculty of Seisen University, Tokyo, for his eloquent translation of Chapter Four of Ishimure Michiko’s historical novel about the Shimabara Rebellion, Hara Castle (Haru no shiro), which he is currently translating in its entirety. Allen’s rendition of the text is enriched by his long-standing engagement with the writings and powerful ecocritical vision of Ishimure, who passed away in 2018. In the category of “Already Published Translator,” the prize has been awarded to Dawn Lawson (Head, Asia Library, University of Michigan), for Nakajima Shōen’s A Famous Flower in Mountain Seclusion (Sankan no meika, 1889). Lawson’s translation makes available in English for the first time a full translation of the novella by the woman who, under the name Kishida Toshiko, was a powerful orator of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement and a key figure in early struggles for women’s rights in Japan. The translation renders into delightfully readable English Nakajima’s witty satire of Meiji mores, as well as her depiction of the isolation often endured by women who, like herself, pursued lives that did not entirely conform to patriarchal norms. In the category of “Unpublished Translator,” the prize has been awarded to Max Zimmerman, of Nikkei America, for translating the short story, “An Artificial Heart” (Jinkō Shinzō, 1926) by Kosakai Fuboku. Like the Lawson translation, Zimmerman’s text makes available in English for the first time the work by an acclaimed pioneer of science fiction in Japan. Zimmerman’s meticulous and concise prose well captures the style of this breakthrough piece by Kosakai, a renowned researcher in physiology and serology, whose fictional account of the construction of an artificial heart anticipated the first successful heart transplant by almost sixty years. |

Introduction to Ishimure Michiko’s novel Hara Castle

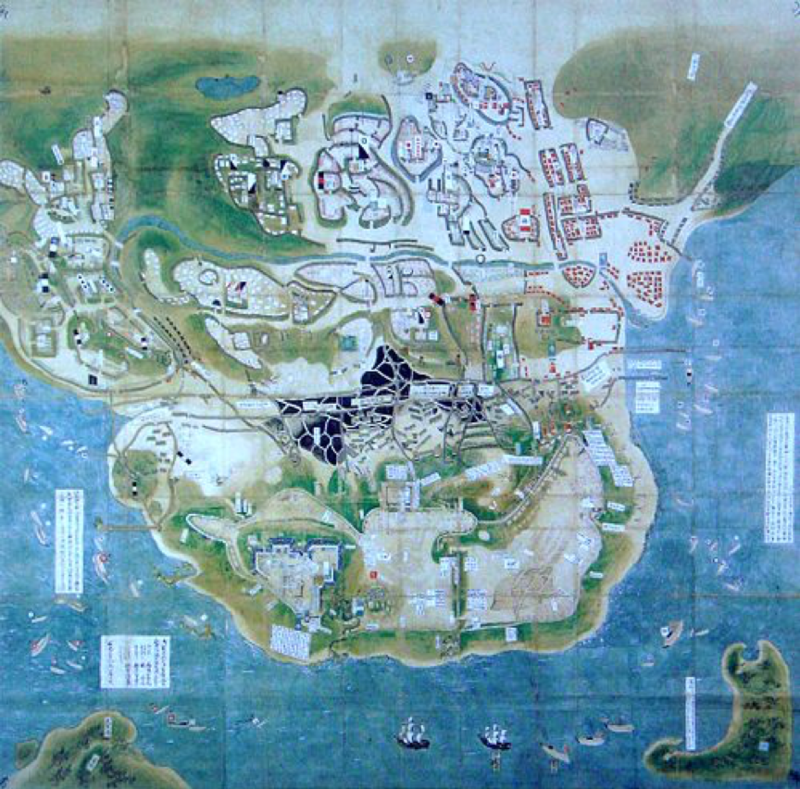

Hara Castle (春の城, haru no shiro) is Ishimure Michiko’s historical novel based on the events that led to the Shimabara Rebellion that took place from 1637-1638 in the regions of Shimabara and the Amakusa Islands in Kyushu.

|

|

This uprising ended with the killing of some 37,000 Japanese—mostly Catholic peasants—in one day, when the Rebellion was finally crushed by government forces. The novel is based around the story of the historical figure Amakusa Shirō (1621-1638), a charismatic youth who at the age of fifteen became the leader of the Rebellion. It deals not only with religious persecution, but also with a wide range of economic and social issues, including the exorbitant taxes levied on peasants by the central government. The events occurred nearly 400 years ago when Japan was looking outward and experimenting with international trade, new religions, and cultures. Ishimure spent fifty years writing Hara Castle. A monumental work of 530 pages in Japanese, it has been considered by many to be Ishimure’s most important work.

|

|

Ishimure Michiko (1927-2018) has long been strongly associated with her pioneering novel Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow (苦海浄土:わが水俣病) , which exposed the Minamata Disease incident of industrial poisoning. Ishimure went on to publish over fifty volumes in a wide range of genres, including novels, poetry, essays, noh dramas, children’s stories, and memoirs. Along with Ishimure’s association with the Minamata Disease incident, her writing has been strongly associated with her concerns for animism, Buddhism, Shinto, and local Japanese myths and folklore. In Hara Castle, Ishimure addresses historical events that took place 400 years ago during the early Christian era in Japan—relating them to her ongoing concerns for justice, environment, culture, and understanding among humans.

Here we present Chapter 3, “The Tree on the Hilltop” and Chapter 4, “Vocation” from Hara Castle.

Note on the title:

This novel was first published in serialized form in newspapers under the title Haru no Shiro (春の城). In book form, it was first published in 1999 under the title Anima no Tori (アニマの鳥) by Chikuma Shobo Co. Later, it was republished under the title Haru no Shiro (春の城) in 2017 by Fujiwara Shoten. Haru no Shiro is included in Fujiwara Shoten’s 18-volume critical edition of the collected works of Ishimure Michiko. My translation of the title as Hara Castle is based on the Japanese title Haru no Shiro. I chose to work from this title because, of the two Japanese titles, it is the one that Ishimure Michiko preferred. The title Haru no Shiro would translate, literally, as Spring Castle, but I translated it as Hara Castle the name of the castle that has central importance in the novel—the site of the historical massacre—and because Ishimure’s use of the word haru carries multiple, nuanced meanings that refer to the historical Hara Castle, to the image of its green fields in the time of spring, and to the Shimabara region, where the events took place and where the remains of the Hara Castle can still be seen.

Brief synopsis of characters and events leading up to Chapter 3, “Tree on the Hilltop,” in Hara Castle, by Ishimure Michiko

The story of Hara Castle begins when Okayo, a young woman who comes from a Buddhist family but also has Christian relatives, marries Hasuda Daisuke, from a Christian family that lives in a neighboring village in the Amakusa Islands of southern Kyushu. They are brought together by Yazō, the leader of the local fishermen and a trusted facilitator of relations among people in the local communities.

We learn of the growing troubles—economic, political, and religious—facing people in the Amakusa region, a historical center of Japanese Christianity. The local farmers and fishermen have been struggling with food shortages and with exorbitant taxes demanded by the central government and collected by local magistrates. In recent years, the Order of Expulsion of Christian Priests (1614) has led to the widespread suppression of Christian beliefs and practices. Increasingly onerous taxes have been levied by local officials to support the Shogun’s expansionist plans including waging distant campaigns in the Philippines.

The Hasuda family, comprised of Okayo and Daisuke, along with the father Jinsuke, the mother Omiyo, and their adopted daughter Suzu, plays a leading role in maintaining their community during the difficult times. Jinsuke goes to the local government magistrate to protest against the grain tax but is rebuffed. The people face worsening conditions of drought, crop failure, and the threat of starvation. Their Christian principles are continually tested and threatened. Nevertheless, they continue to carry out charitable activities such as maintaining a “Mercy House” for elders who have no other relatives to support them. They try to maintain their Christian faith, secretly, amidst the increasing conditions of its suppression.

The Ninagawas are another leading family in the town. Their son Ukon became a close friend of a charismatic young boy named Shirō—who will eventually be chosen as the leader of the Shimabara Rebellion—when they met during a visit to Nagasaki. The two share interests in study and religion.

On his boat, Yazō has just brought Shirō to the village of Kuchinotsu and introduced him to the townspeople. After a long period of drought, the weather changes and a great storm approaches.

Brief synopsis of characters and events leading up to Chapter 4, “Vocation”

We are introduced to Okatchama, a woman born in poverty in a Christian family. She had been a prostitute, but later became a powerful, respected businesswoman in Nagasaki. She plays a major role in supporting the Christian community, as well as in helping immigrants and children of “mixed-blood” marriages. She also has a major influence on Shirō and Ukon; introducing them to each other, and teaching them about practical matters of living in the world.

The area suffers a major typhoon that seriously damages houses, fishing boats, and crops. It also claims the lives of all the elderly residents of the Mercy House. Increasingly, the people suffer from bad weather—both drought and flood—and they come closer to starvation. In these desperate conditions, Hasuda Jinsuke petitions the local government for a deferment in paying the grain tax; both for the current year and for the amounts owed from recent years of poor harvest. He also asks for an emergency allotment of rice, as the people face starvation.

|

Ishimure Michiko and Bruce Allen; Ishimure Studies Center, Kumamoto, 2007 |

***

Chapter 3 : Tree on the Hilltop

Swirling over the cape off Kuchinotsu harbor, the first strong gusts of wind swept along with big drops of rain. After so many days of scorching heat, the rain came as a great relief as it fell on the sweaty men. Soon after, to their surprise, the wind died down, and here and there, the sound of hammering started up suddenly. And then, as it fell silent, the light of day faded.

The roaring of the sea drifted in from the coast nearby. Okayo, more agitated than usual, looked at her husband’s face with a forlorn expression. Daisuke was sitting next to his father, and turning the pages of the accounts ledger. The light from the oil lamp was weaker than usual. As a precaution, on account of the wind, its wick was trimmed low, and he was reading the small characters in the dim light.

“Hmm, the tide’s out. Sounds like it’s kicking up more than usual out at sea.”

As Daisuke said this, he sensed Okayo’s gaze fixing on him. Matsukichi, who had been weaving straw sandals in the dark earthen-floored room, stood up, holding his work in his hands.

“Looks like the tide’s going to run real strong tonight. When it comes in, it’ll be a high one.”

With Matsukichi’s talk of the sea, Okayo felt a bit relieved. Jinsuke stopped writing and looked up.

“Well, I’m glad to see it’s gotten dark enough. Now’s the time. We’ll get some people together. You ready?”

The men all stood up. In preparing for the storm, while working together in the room with the attached dirt entryway, they had been keeping their ears tuned for signs from outside. Daisuke nodded to Matsukichi, and, as if being sucked into the hushed silence outside, they headed out.

As she watched the men starting to move quickly, Okayo also worried about the supply of grain. She imagined they must be trying to get the grain that Yazō had unloaded from the ship earlier in the day. When the high tide came in, they wouldn’t be able to use the road along the beach. When Jinsuke said, “Now’s the time,” he must have been talking about their going to get the grain, and sharing it with the villagers without being noticed by the government officials. If they went now, there would still be time before the tide was high. And the darkness would help keep the movements of Daisuke and the others unseen.

The government grain storehouses were on the other side of the inlet, across from the boat. If the guards noticed the movements of Daisuke and the men, they would confiscate the grain, wouldn’t they? Okayo heard the sounds of the whirling sea growing louder, as if pressing down on her, and she glanced at her mother-in-law.

Despite all the consternation of the night, Omiyo was starting to sew a finely decorated ball. In the dim light, she continued sewing the strands of red thread into it. In the darkened room, with the men gone, the small ball cast a faint light.

On a straw mat, Oume was slowly crushing dried mugwort. Sorting out the bits of down that came from the leaves, she was preparing mogusa for moxa treatment.

“What with the storm and the drought both coming together, we’ve had quite a time of it, and today’s been so crazy. But if we get enough rain, and it doesn’t bring too much trouble, let’s celebrate.”

Omiyo said this to Jinsuke, who looked worried about Daisuke’s absence. Just then, a tremendous gust of wind struck as if it might pull the roof down.

“Whoa!—here it comes! Looks like it’s hit.”

Biting off the end of a strand of red thread, Omiyo glanced toward her husband. Her mother-in-law smiled gently. While Okayo was musing on how much Omiyo resembled the Kannon at Nie no Ikawa, the lamp went out. Remaining in the back of Okayo’s eyes was the impression of how the ball in Omiyo’s hand looked so much like the sacred orb of Kannon-sama. The remaining group relit the little lamp below the creaking ceiling, and held evening mass.

In Ninagawa Sakyō’s house, in the midst of the storm, his family passed the time as if buoyed up by the depths of an enormous wave.

Ever since their son Ukon had met Shirō in Nagasaki in the spring, the two had formed a close relationship. Already, Ukon had become worried that, along with the eviction of the missionaries, the Christian books that had been printed in Amakusa, Katsusa, and Nagasaki were being scattered and lost. He hoped to collect the remaining books and other documents, and save them. Henmi Juan had strongly urged him to do this. He had requested:

“While I’m still alive, please collect as many of the writings as possible, and ask me about anything in them. I want to pass on all that I learned at the seminary and the college.”

And then, he had visited the Ninagawa house, and discussed academic matters. During the past thirty years or more of oppression, a number of people had been imprisoned just for possessing Christian writings. Some had burned the books and documents before they were found, and Juan worried that if books such as the Doctrina Christiana and other writings on the faith’s important points were lost, all the carefully-preserved essence and spirit of the prayers would come to naught. His worries also reflected certain pressures that sometimes overrode the pleasure he took from scholarly work in his old age.

Fortunately, Yazō had made good use of all his connections in Nagasaki, and had been searching patiently for any Christian books that had been hidden away in secret. In the spring, he attended a tea ceremony to which Juan had invited Ukon, and with great joy, he announced, “I found these. They were all in one place.” Juan was so happy he almost spilled the hot water from the wooden ladle he was holding.

Soon after, Ukon had gone with Yazō to Nagasaki, and they met Shirō in the house where he was living temporarily.

First, they were introduced to the slender woman who was in charge of the house. As Yazō had already explained to Ukon, she had been one of the supporters back when the town village ran the Mercy House.

With a sense of fondness, as if already knowing a lot about Ukon, the woman had said, “Well, I’m so glad you’ve come. I’ve been hoping there might be someone who would keep these things. You’ve arrived at such a dangerous time.”

Looking at the two, who at first, were surprised to hear her warning, she continued:

“Yes, listen—yesterday, the police raided a Chinese ship. Someone must have informed them.”

“Really? Did they find anything on it?”

“They found a Christian book. A Chinese sailor had it, but nobody could read it—or so they said.”

“They couldn’t read it because it was written in Chinese?”

“No, it was in some European language—and its cover had some prohibited Christian designs on it. They took the sailor off the ship, and threw him in jail.

“We’ll have to be careful.”

“I’ve been so worried, waiting for you to come. Unless we get these religious writings away from Nagasaki, and hide them somewhere, I’ll be too ashamed to face the priests.”

“Well, thank you so much for taking care of them until now.

“It’s a relief to me—a big load off my mind. Will it be you keeping these books?”

The woman had appeared to be a bit over fifty. With a long, deep sigh, she gazed at Ukon.

“I’m so grateful you’ve been looking after these precious books.”

“Don’t mention it. I’ve heard such good things about you from Yazō-dono, and now, from meeting you, I can see you’re the person I’ve heard about.”

Ukon blushed.

“Well, anyhow—my thanks to you. Now could I ask you to wait just a bit longer?”

The woman stooped, and went off into the back of the house. Outside, it was already starting to get dark.

He had heard that this was a shop that dealt in Chinese goods, and in the back, there was an earthen-floored room with shelves on both sides. On them were placed an old statue of the Buddha, a beautiful brass flower vase, pieces of ivory, and other such things. The room had an indescribable fragrance. Ukon found himself sniffing the air, wondering if these might be the smells of musk and aloeswood that Juan had spoken of to him.

When his eyes had adjusted to the dim light, he realized that the room also contained various lustrous fabrics decorated with woven designs. He wondered if these might be the damask silks and figured fabrics his mother had told him about. And then Yazō, rubbing his thigh, called out:

“You find them interesting?”

“Very much so. And do they also sell fragrant woods?”

“Yes, they do. Ah, that’s right, Ukon-dono, you studied tea under Juan, so you must have a special interest in such woods.”

“I’m not especially interested, but a while back, my master said he wanted to try burning some aloeswood.”

On Christmas Day, after the ceremony, Juan had the custom of offering tea to his friends. Although he didn’t burn aloeswood at most tea ceremonies, he had a special feeling for it on Christmas, and he burned it in the tea room. He used to say that Father Valignano was very knowledgeable about the tea ceremony. He explained:

“Some of the Christian daimyo were among the most distinguished followers of master Sen no Rikyū and they tried to obtain the finest incense for burning. But Valignano-sama used to say we shouldn’t make a lot of smoke when we burn an aromatic wood, even if it’s a good one. Instead, we should burn it as a faint, refined incense.”

Together, the two men recalled such comments they had heard from Juan.

I’ve never seen it, but I’d like to burn some aloeswood incense, even just once.”

When Juan mentioned this, Chijiwa Bannai, who had been present at the tea ceremony, called out abruptly:

“Speaking of incense, these days we don’t hear any more about putting it in our armor when we go off to battle.”

“In armor for going off to battle? Hmm.”

Falling silent, a faint light shone from Juan’s deep-set, half-opened eyes.

Being in this shop filled with smells so different from those in most homes, Ukon had felt as if he were hearing Juan’s voice from that time, calling out in his ears. When Ukon looked up, he found a young boy standing silently right in front of him, holding a lamp covered with a paper shade.

“Might you be Ukon-sama?”

Reflexively, Ukon stood up.

“The Okatchama asked me to show you in. Would you please come this way?”

“Okatchama” was Nagasaki dialect, meaning the woman of a large household. Though it was still before sundown, the inner garden, which extended out from the dirt-floored entryway, and was lined with trees, it was quite dark. Turning the paper-shaded lamp around, the young boy turned his head back.

“Watch out for the roots of the wisteria vines as you walk.”

In the lamplight, the vines of the wisteria seemed enormous, like giant snakes. Beyond the trees, a brighter light was shining from another room.

Okatchama, who had been waiting, opened and spread out a purple cloth furoshiki on the top of a sturdy desk.

“Well, now I can show you these books—at last. First, could you check them, please?”

She called out to the young boy, who was about to stand up.

“Let’s bring in the candle stand we use when we read the Oratio.”

Ukon watched the boy closely as he left the room, nodding.

“That boy’s a bit different. I’ve been looking after him.”

Despite the woman’s words, Ukon remained concerned about the boy, since he acted so differently from most merchants’ sons.

Under the light from the candles the boy brought in, Ukon was finally able to take a good look at the treasured books such as the Guia do Pecador, the Hidesu no Kyo, which was the first chapter of the Symbolum Apostolicum, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Spiritual Training.

“Please, take these in your hands and read them.”

After looking over the covers of each book carefully, one by one, front and back, Ukon began turning their pages. Seated beside him, the young boy also gazed at the books. Touched with deep emotion, Okatchama watched the two. Glancing at Yazō, they had both nodded.

On the evening the storm hit, in the Ninagawa house where Yazō brought Shirō, and amidst the gracious reception he received there—so gracious that it had almost made him writhe in pain—Shirō had felt a certain heaviness. Later, he learned that the Ninagawas’ second son, who had been the same age as he, had died the year before in an epidemic. Perhaps when the family looked at Shirō, they saw their son superimposed on him.

Now meeting again, the two young men recalled their deep feelings from that evening in Nagasaki. The creaking and groaning that came from above sounded to them like the cries of a monumental trial from God.

“I wasn’t able to ask about the landlady at the house in Nagasaki then. What sort of person was she?”

The reason Ukon wished to know about the Nagasaki landlady was because he had been so impressed by her parting remarks. On the morning after he received the books from her, just when he was about to say goodbye, suddenly, with strong emotion, she had said to him:

I’ve taken care of these books until today, and I’ve been praying every day, morning and night. Twenty years ago—you weren’t even born yet—I’ll never forget. It was in the year of the tiger, and here in Nagasaki, at risk of our lives, we held a sacred procession. It had been reported that the Nagasaki governor had boasted that he was going to destroy the cathedral—down to its very last stone—and that he was going to force all the Christians—to the very last one—to renounce their faith. And so, in groups, the believers got up, and swore an oath of allegiance to their faith, and asked Deus for mercy and for forgiveness of their sins. And then, they marched through the city from church to church.

The seven groups kept up their marches for a number of days, and in the procession, some did penance. Clothed in purple, they carried crosses on their backs, such that the muscles of their shoulders were ripped and torn. They scourged themselves with whips until blood flowed. Children, too, dressed in purple, marched along chanting prayers. It was such a moving procession. Resigned to their fate, and with a beautiful statue of the infant Jesus placed on a carriage stand, they marched with their palms pressed together in prayer. Even people of other faiths formed lines, and watched in silence.

These books were given by the padre who stayed at my house at that time. I joined the procession. Soon after, the padre, too, was hung on a cross . . . These books bring back memories of that day in Nagasaki, and of the repeated voices of prayers. I would like to present these books to you—along with their eyes, their images, and their spirit.

After some hesitation, Shirō’s voice broke through Ukon’s reminiscences.

“That Okatchama—I don’t really know what sort of person she was. Her name was Onami-sama, and she was both extremely strict and kind.”

“Onami-sama, was it? I’ve never met another woman like her, and I can’t forget her. It was an unusual house.”

“It sure was unusual. And there were lots of women in it.”

“Because it was a merchant’s house?”

“No. They came to ask for her advice. I heard from people who knew about it that she’d been a prostitute.”

Ukon looked at the young boy with deep seriousness.

“Magdala Maria—she had been a prostitute. She shed tears on Christ’s suffering feet, and anointed them with scented oils, and wiped them with her long hair.”

“I remember hearing that name.”

“She was the woman who, after Christ was hung on the cross, went to the cemetery, where she met an angel, and heard the prophecy of his resurrection.”

“You know lots about it.”

“I think of Onami-sama as a reincarnation of Magdala Maria.”

“Why is that?”

“Other women who look like they, too, might be prostitutes come to see her, and she listens to their stories. They get some peace of mind after their stories have been heard. Okatchama sees them off in tears.”

Reflecting the candles’ wildly flickering light, Shirō’s eyes, with their long eyelashes, stared at Ukon, deep in thought. It seemed strange to hear such a story from someone as young as Shirō. Ukon pondered, I’ve never thought about the lives of prostitutes—never even considered that their world might have any connection to mine. Yet here, this young boy has been trying to spread the light of the Savior, in order to help the lives of prostitutes. Ukon realized the depth of Shirō’s spirit.

Come to think of it, that time when I left, the landlady whispered to me, “That boy has been my guardian angel. Please consider him a brother, and always help him.”

After the churches were destroyed, the groups of believers gathered together in the invisible temples of their hearts. That landlady’s house must have served as one of Nagasaki’s invisible temples.

“Okatchama laughed, and said you weren’t cut out for business. But what she did there, even though it was in a merchant’s house, was something entirely different from business.”

Shirō smiled with an almost angelic expression.

“If you just rely on numbers, then everything around you becomes limitless, and finally, it becomes empty.”

“Empty? Well, perhaps you’re right.”

“But if you say that, then reality is empty. It becomes meaningless.”

Ukon stared at Shirō’s mouth, trying to understand what his words meant.

“Everything—and not only humans—once it’s born into this world, it causes something else, and this brings about an effect, and, in turn, this effect becomes yet another cause, and so, everything is bound together without limit. I, too, am also bound up in this endless chain of cause and effect.”

A dense cloud seemed to hover about Shirō’s eyebrows, hinting at his feelings. It seemed that this boy was trying to speak about the kinds of things that had never appeared in Ukon’s thoughts. After a silence, during which Shirō seemed to be looking for an appropriate time to speak, he began:

“To tell the truth, in that Chinese ship, I saw the leg of a child in chains.”

In silence, Ukon watched his face.

“According to Okatchama, that child must have been either sold or kidnapped.”

“ . . . . Come to think of it, now that you mention it, I too heard they were trafficking humans on the Portuguese ships.”

“That child was sold and sent here, but from where? What kind of parents did he have? His toes were all caked with dirt. One of his ankles—he must have been about ten years old—was shackled in iron chains.”

Ukon thought of his younger brother, who died in the epidemic the year before. He had often washed his ankles when he was an infant. And before laying him in the grave, he had carefully washed his toes and wept. Suddenly, he recalled the story he had heard a number of times from his mother about the martyred family of Hayashida Sukezaemon. The image of the eleven-year-old boy and his parents being burned to death rose up before his eyes. The flames had touched the boy’s clothes and hair where he was tied to a post, separated from his parents, and together, they were chanting the name of Santa Maria And as the rope that tied him burned and fell away, he was calling out for his mother, who was also engulfed in the flames. With excruciating breaths, the mother called out to her child, as if embracing him, and looked up to heaven. And then she said:

“Let us go there together.”

Ukon wondered if it was right for him to feel happier about the child who had been called up to heaven in front of all the people, compared to the child whose leg Shirō had seen. The thoughts weighed so heavily on him that he could not speak.

“The kapitan of that ship bought and sold people—and the sailors did it too—all of them could read the Scriptures, couldn’t they?” Shirō questioned.

Ukon just nodded.

“Our world’s in great chaos now.”

“You were talking about emptiness.”

“Right—there’s emptiness, a bottomless void.”

“And do you think it’s from there that the world will be created anew?”

“I suppose that’s the way all things are born and pass away.”

“But if that’s so, then is there no need for Deus-sama?”

“No, that’s not how things are. Actually, that’s the very reason for the existence of the One who contemplates the order of the entire world. It seems that people reflect various aspects of the world, and what they show to others is only one aspect.”

With a grave expression, the boy listened to the storm howling above him.

“Inferno—what do you think about it?”

“By knowing about Inferno, people can know about their own sins. When I saw the chain on the leg of that faceless child, I realized, deeply, our sins and faults.”

“And at such times, where is Deus-sama?”

“Deus exists, there—beyond such things.” The sounds of the wind pressed on the feelings of the two young men. Oily beads of sweat formed on Ukon’s brow. The depths of his eyes turned pale, and he sighed deeply.

As if struck by a bolt of lightning that sent shivers through his entire body, Ukon pressed his palms together forcefully. This was the first time he had ever felt such emotions. Gazing at Shirō with affection, as he realized the undeniable similarity to his younger brother’s face, he found himself at a loss for words. It seems that this boy, here in front of me, has come to this land that has become so wrapped up in the sufferings of the world, and that he is being used to atone for everyone’s sadness. How can I place such an image on this person who is barely fifteen? Staring at Ukon as he considered these thoughts, the boy projected the image of a flame in water.

Even as the storm raged and howled, Ukon’s mother heard the two young men in the adjacent room talking, and occasionally breaking into quiet laughter. She remarked to her husband:

“You know, these days we’ve hardly ever seen Ukon with such a happy face. What do you suppose they’re talking about?”

“Well, they’re young, and they have all sorts of things to talk about. But I wonder if they’re paying enough attention to the wind and rain. We can’t let those precious books get wet.”

A strong gust of wind blasted up from beneath the floor, such that it felt as if the entire house was being lifted up. The husband and wife glanced at each other.

Mizuna shrieked, “Brother—our house—it’s blowing away!” and ran into Ukon’s room. The candle in the stand flickered, and then, suddenly went out. This was the old candle stand from Portugal that their father took such pride in.

“We’re not going to be blown away.”

Ukon said this in a cheerful, reassuring voice to Mizuna, who was standing in the dark, looking petrified.

“I’m scared. Let’s stay together.”

“Mizuna, what’s this fuss about? Calm down.”

Lowering her voice, their mother entered. Holding a hand-held candlestick, she was carrying something heavy on one side. She felt her way forward with her toes, while the entire house sounded as if it was just barely holding together.

“Mother, is our house going to be blown away? It’s making such terrible squeaking sounds.”

“You’re right. It is making sounds.”

“I’m scared.”

“You’re scared? How old are you now? Act your age.”

Mizuna was two years younger than Shirō.

“Brother, let’s stay with Mother.”

“Your brother and our guest have important things to talk about. And it will be better if we sit in several places to help hold the house down—isn’t that right, Ukon?”

The hand-held candle cast its flickering light on the laughing faces of Ukon and the guest.

“Here’s some oilpaper.”

Setting down the load she had been carrying at her side, the mother looked up at the ceiling.

“Looks like the rain hasn’t gotten to them yet. Talk’s important, too, but those books—could you ask our guest to help wrap them in this oiled paper? And, Mizuna, don’t just stand there, why don’t you fix the candles in the stand?”

Around daybreak, Ukon woke up, vaguely sensing some sort of commotion going on around him. It sounded like fragments of people’s voices. He had talked on long into the night, and worked hard at taking care of the books, and then fallen into a deep sleep. When he woke and looked around, he noticed that straw had fallen from the ceiling and lay scattered all over the tatami floor, and there was a smell of soot. The soot was strewn over the edges of Shirō’s futon.

“Last night, Ukon talked on so long—you mustn’t have gotten much sleep.”

Ukon’s mother’s face expressed a look of apology.

Mixed with the odors of soot, the smell of porridge wafted into the room, and then, breakfast was underway.

“That was one heck of a storm. Today, the sea’s still rough, and the boats won’t be sailing.”

“Please stay with us as long as you like.”

With this, Sakyō, the father, entered the conversation. He presented an image of conscientious seriousness, but when he spoke, his look was pleasant.

When Ukon stepped outside and looked around, he was astonished. The house’s straw roof had become twisted and warped. On top of it lay broken branches from a large bough that had blown over from the neighbor’s camphor tree. Limbs and branches had been broken and tossed through the front garden, blown along the street such that it looked like it would be difficult to get away from the house without doing some cleanup work. While Ukon was surveying the situation, Kumagoro, a worker at Jinsuke’s house, came rushing up, his hair disheveled.

“The old people at the Mercy House! They’ve been swept away by the waves!”

“What?”

“And the house—the house was swept away too!”

Everyone stood bolt upright.

“Osuzu and Okayo-sama—they’re at their wits’ ends. They’ve been going back and forth to the beach. We couldn’t hold them back.”

“So what’s happening there now?”

Sakyō urged Kumagoro to continue.

“We’ve formed groups, and they’re out searching the coastline. But my master, he says he has something urgent he needs to talk to you about. He said he should have come directly, but, as you can imagine, he’s completely caught up in the work, and so, he asked if you could come to him.”

Asking on bended knee, as he looked up at Sakyō, Kumagoro’s shoulders were shaking. After drawing a breath, Sakyō replied.

“I understand. I’d like to go there now, but we have a lot to deal with here too. Tell him that as soon as we clear things up a bit here, I’ll go.”

Sakyō turned to his son.

“All right then, let’s get to work. First, we need to take a look around this place, and find out what’s happened. Ukon, I want you to go out and check on things.”

“Okay, right away.”

“I don’t want you to rush and overlook anything.”

“I’ll be careful. And will Shirō-dono go with me?”

“I’ll go with you.”

During this short discussion, people had been coming in to report on the damage. Shirō soon had a clear understanding of this family as the center of the confraria group of believers. Mizuna came in, and immediately started cleaning up the rooms that had been covered in soot. She worked briskly, looking very different from how she had looked the night before. Messengers came in, one after another.

“As far as I can see, there are no houses that have escaped damage.”

“The embankment and the roadway to Ushikubo’s place—they’ve been washed out.”

“Jisaku’s fields are so covered in mud they’re not recognizable.”

“And the tide washed up over Yozaemon’s fields, and pushed the gravel and debris all the way up along the river.”

Hearing these reports, Sakyō spoke in what sounded like a moan.

“Yozaemon’s fields?”

Yozaemon was one of the leading farmers of Kuchinotsu, and one of the leaders of Sakyō’s confraria group as well. His rice fields were set along a small river that led into the ocean, and people knew that, even in times of drought, the little water wheel there would be turning and drawing water into the fields. By means of various contrivances, he had made sure that water reached the neighboring fields as well, but people couldn’t help noticing the different color of the rice in his fields, and even if the water dried up in the river, the grains of rice in his fields were full, and he could still get a decent harvest.

He lived simply and frugally, but a number of times, when things had gotten hard, he had opened his grain stores and given freely to others. And so, people spoke quietly of “Yozaemon’s storehouse of compassion”.

Sakyō remembered Jinsuke’s messenger, and considered the gravity of the situation. His wife, with her kimono sleeves tucked back, brought in tea, and silently placed it in front of her husband. Then, in a small voice, she spoke.

“I have to say, our grain stores—they’re almost empty. Last night, Yazō brought us about five portions mixed with azuki beans for the guest, and so, for breakfast this morning, I made some porridge with beans for the first time in ages.”

Sakyō’s face snapped back to attention, and he returned his wife’s look. Until that moment, his wife had hardly ever mentioned the state of affairs in the kitchen.

Sakyō thought, Haven’t I just taken it for granted that my wife would take care of things all the time? I’ve been so wrapped up with things like the land taxes and the rice levy that I haven’t even asked her about our own household affairs. How has she managed up to now?

“So, you’re saying . . . our stores are empty?”

“I didn’t say they’re empty. We still have a little millet and some soybeans. And we have a few of those small summer beans from last year.”

“That bad, is it?”

“Well, yes, but with all this rain we’ve had, perhaps we can plant an autumn crop of vegetables like daikon and some other things.”

They held this quick conversation while people were coming and going. Sakyō felt uneasy, since, once again, he realized how he was not only the leader of a group of Christians, but also, the head of his own household. While he watched over the people who passed in front of him, he thought of their rules and faith, which connected all of the believers. For them, he would certainly give his life. But even if he put all of his effort into memorizing and putting into practice all of the rules, it seemed of no use in the terrible situation they now faced. No, he didn’t say it was futile, but in the rules alone, he couldn’t find the strength he needed to step forward, and clear a path to resolving their predicament.

That happy time they spent at breakfast together with the young guest, thanks to the grace of God, mixed with the good smells of azuki bean porridge—what had that been? Sakyō told himself to stop feeling weak, and he raised his head.

In the field, an old holly tree had been completely uprooted, and lay upturned and leaning on its side. There was a hollow in it, covered with little green berries. When winter came and the berries turned red, birds would flock to it and pick at them. But he had never heard of humans eating them. Sakyō chided himself for thinking such stupid things.

Sakyō was glad that Ukon, who was normally absorbed in his studies and didn’t pay much attention to mundane affairs, now showed a different look and stepped outside the house. Sakyō thought, The Christian teachings don’t come from the written books. It’s at times like this that Ukon has to find the true, living meaning of the teachings, through his actions. He needs to find it himself.

Sakyō continued, But what should I do, and how should I do it? I hear starvation is hitting all the villages around here, and that in other places, people have started whipping themselves, in penance and to ask for help. I’m not thinking of doing that, but if it’s God who does the whipping, I’ll take it. The whip, it seems, will come from both outside and inside. I’m ready to stand up and take the pain.

With a serious expression, Sakyō listened attentively to the grave reports. There could be no doubt that other villages were also in a critical situation. He thought it necessary to call an emergency meeting with all the village heads and leaders who had been summoned to the governor’s place the other day, so they could make plans and take some countermeasures.

Sakyō would be able to go to Jinsuke’s house a little after mid-day, once he finished looking after things here—for the time being at least. One elderly person from Sakyō’s group had been sent to the Mercy House, which was now washed away. Soon after Kumagoro got back, Sakyō had sent some people to Jinsuke’s house to search for the missing old ones. But because of the huge waves—the likes of which people living by the coast had never seen before—other houses too had been washed away. And more than ten of the boats, which people had drawn up onto the land or tied to sea fig trees, had been washed away and were missing, too.

Jinsuke and Daisuke were talking to the people who had come to help, and all looked distressed.

“Building that Mercy House so near the coast, it certainly was a mistake. That place was the home for our precious people. There’s no excuse for it.”

Jinsuke knelt on the ground, and for a while, was unable to raise his head. The decision to build the house there had not been Jinsuke’s alone. The leaders had decided on it together after going to check the site out.

The people in the area, even those who lived in the mountains, had loved going to the seashore since their childhood. They enjoyed watching the boats coming and going, and the many people who passed by there. On days of good weather, they enjoyed digging for shellfish, and listening to the voices of children playing. They had chosen the site thinking of how the old folks would enjoy such things, and how the area had no places with dangerous footing. And so, they had put up a simple building there. But now, these considerations had turned out for the worse. They should have built it on higher ground.

Without raising his head, Jinsuke said, “I regret it deeply. . . It looks as if I built the house there so it would be washed away. . . .”

“Don’t say that. Don’t talk that way. It was a natural disaster. It couldn’t have been helped. Everybody knows the old people in the house were well taken care of.”

As he spoke these words of consolation, Sakyō looked about for Suzu. She was an orphan who had been taken in by this family. People knew she thought it her responsibility to take care of the old people in the house, and actually she did much more than the adult caretakers. But she was nowhere to be seen.

Kumagoro said that Suzu had lost her mind. It was understandable. She was probably off somewhere, hiding and crying.

Sakyō added, “It can’t be helped. First, just stand up. There are lots of urgent matters we have to take care of.”

Jinsuke now looked as if he had shrunk in size. Daisuke was standing quietly behind him with his mouth shut firmly. His normally easygoing face had turned pale.

“Daisuke-dono, how many years apart are you and my son Ukon?”

“I’m five years older. But I don’t know anything about studying.”

“Well, all he knows comes from books. He doesn’t know the first thing about farming, or about people. You think you might teach him something about the fields and the eggplants’ flowers?”

All around, people chuckled a bit, and suddenly the heavy feeling was relieved. Then, Yazō came tramping in with a group of young people.

Those who had been seated rose to half-standing. They wanted to express thanks to Yazō for the grain he had brought in the night before, and they also wanted to express their sympathy for his missing boats. But above all, just seeing the face of this man renewed their spirits.

“Well, that sure was some wind we had last night.”

Both groups spoke of the same thing together.

The village chiefs and family groups had all met from time to time in the past, but today’s gathering was an especially varied group. In part, this was owing to their having rushed in without time to fuss about clothing, but it brought them cheer to see each other. And now, thanks to Yazō’s appearance, everyone’s spirits were suddenly revived. And when Ukon and Shirō came in, the place gained an even greater liveliness.

Noticing the unusual young man that Ukon had brought in, people focused their attention on him, and the boisterous room turned quiet. In the back of the room was Juan, puffing smoke from a long-stemmed pipe.

“Sensei—thank you for taking the trouble to join us,” Ukon said to Juan, and he started to bow in greeting with his hands on the floor. Between puffs on his pipe, however, Juan just said, “Well, no,” and with his jaw jutting out, he gestured in the direction of Jinsuke, as if to indicate that Ukon and Shirō should greet Jinsuke first.

Yazō, watching the two, glanced respectfully toward Jinsuke and his son, and then, broke out in a smile. It was clear that since the previous night, they had formed an easygoing relationship. He was glad that Shirō had stayed with Ukon’s family. Perhaps, he thought, the bad weather had provided a good chance.

After Ukon finished reporting on what he had seen, the crowd that had assembled before his arrival began to head back to their homes. They all felt worried about what was happening around them. Those who had left old family members at the House took particular care in offering words of consolation to Jinsuke before heading home. This made a deep impression on Ukon.

If three days passed and there were no signs of survivors, they would do a burial on the top of the hill facing the sea. Until then, they would concentrate on taking care of the casualties. And together, they would make sure there would be no more mishaps. Hearing everyone talk together in this way, Daisuke felt deeply grateful. A casually-asked question from one of the people stuck in his chest.

“Haven’t you seen Suzu?”

“She must be heartbroken.”

Hearing these words brought tears to Daisuke’s eyes, and he felt ashamed. Seeing his father dejected like this, for the first time, he clenched his fists tightly and thought, I have to get a hold of myself. Having received silent encouragement from the Ninagawa father and son, and from many others, he could not do nothing.

They found four people who had died together. But any thoughts of how the leaders might have built the old people’s house on a higher spot were now just the wisdom of hindsight. The House was proof of their unceasing faith, and it had been built according to the rules of their beliefs.

The okite commandment says, “Care for your neighbors as you would for yourself.” But “as you would for yourself”—what does that mean? Daisuke put the question to himself. And then, he noticed his father’s back.

Looking from behind, he could see that his father’s neck was completely bent over. It seemed his father must also have been taking the questions of the okite to heart. Confession before the Lord—this feeling now—is this what it’s about? Daisuke asked himself if he was truly a believer.

Since I’ve been brought up in a Christian family according to its rituals and beliefs, I’ve become accustomed to foreign practices, and accepted them without doubts. In town, there are some Buddhists. But even when I hear the old folks reciting their namu-Amidabu prayers, it seems like they’re just practicing some old-fashioned tradition. Well, the padres used to say those peoples’ beliefs were the talk of the devil—though I don’t agree with that. But those “heathens”—they also came running to help us, and they’ve helped with the search and the distribution of food to the victims.

Any feelings of superiority I might have had towards “heathens” now seem vain and pointless. And when I think of what Suzu has been doing, I feel ashamed that I’ve just acted on the surface, as if I were her protector, since I’m the son of a village chief. Isn’t it Suzu, who, with her own body, has followed the okite “Care for your neighbors as you would for yourself?” Me, I’ve only mouthed the words, and recited them as a matter of form. There’s been no spirit behind my beliefs and my faith.

When I held Suzu—she was clinging to a sea fig tree, shaking and looking at the sea—I felt as if I’d been struck by a bolt of lightning. With her body shaking, that child—she wasn’t even ten—she went off searching for the old people who, until just yesterday, she’d taken care of. And now, she can’t eat or drink.

She was staring the adults in the eye questioningly—realizing that she couldn’t get answers from them, and not knowing how she could appeal to anyone about all the things she couldn’t hold in her young heart—facing the sea and shaking.

Not knowing how to take care of her, I . . . I couldn’t approach her easily, or quickly. Could it be that this orphan has been sent in the service of our Lord? When I held Suzu, the words of the okite rung in my head like reverberations from a cracked bell. I wonder if we can ever truly care for our neighbors as we do for ourselves. Those are truly frightening words.

What sort of people were those old ones washed away by the high tide? I’ll have to ask Suzu about it again. This is my own confession.

Gazing at his father’s back, Daisuke took these things deeply to heart. Then, he realized that someone was approaching him. When he glanced around, he saw that Yamada Yomosaku, the artist, was approaching, sliding toward him on his knees. Thrusting his head forward, Yomosaku spoke to the Ninagawas.

“With all that’s going on now, I’m sorry to ask you, but I wonder if all those books and writings you have in your house are safe.”

Since most of the former crowd of people had already gone home, those who were still left heard the voices clearly.

“Well, fortunately, they’re all right.”

When Ukon lowered his head, Yomosaku heaved a sigh of relief.

“Well, I’m glad to hear that. As for me, ten or so of my paintings and canvases got rainwater on them.”

“That must be a disaster for you.”

Seated at his side, Sakyō leaned forward, and expressed his words of sympathy.

Yomosaku nodded slightly. He rolled the thumb of his right hand, moved his mouth, and spoke quietly—as if talking to his fingers.

Yomosaku had studied painting at the art school connected to the Shiki Seminary, and he was one of the artists who had painted the altar of the cathedral. The believers had called it the “holy figure,” and they displayed it at every ceremony. During the Arima era, he had been supported by the clan leader, but he had stopped serving the Arima after the apostasy of their lord, and the fief’s transference to Hyuga. He showed up occasionally at the gatherings of the believers.

Even after the change to Matsukura rule, he had continued to do well, and people in power continued to pay for his art supplies, commissioning him to paint screens and such, so he was able to make a living. He was of a different temperament, apart from both the samurai and the farmers, so he was seen as a somewhat unusual sort of person, and treated as a special case.

With arms folded, Juan asked, “So will you be able to get some canvas to make up for it?”

“Well, there might be some ways,” Yomosaku answered, gazing off vaguely into space. Juan and Sakyō worried that this matter might become another burden for Yazō. It was said that his canvas was made of a specially woven sort of silk material. For the farmers and fishing folk who could not read written words, the “holy figure” held a particularly important significance. For the sake of the confraria as well, it was essential that Yomosaku continue painting.

As Daisuke listened to this discussion, he realized how even among the believers, there were unusual sorts of people. He felt this enabled him to look at things with a wider perspective. As he watched Yomosaku leave, and as the remaining people began to stand up, a young voice called out,

“Thanks for all your help since we met yesterday.”

Shirō was placing his hands on the floor greeting Jinsuke.

All the visitors heard somewhat muffled voices, and looked closely at the two.

“I heard about what happened at the old people’s house. Everyone says you’ve taken it to heart for so long. It pains me too. This terrible event will remain with me throughout my life.”

All the adults thought that they, too, had been talking about the same things. And yet somehow, there was a difference. In Shirō’s voice, his soul spoke out. At first, Jinsuke seemed lost in thought, but then, he replied, “Yes, what should I say . . . ?” And then, he stopped speaking and bowed. Even after bowing, he could not control his feelings, and he blinked his eyes.

“Sorry to interrupt, but I have something I’d like to ask Daisuke-dono.”

“All right.”

“Since yesterday, I’ve been wanting to meet that girl Suzu.”

Daisuke nodded as if he already understood.

He replied, “Could you wait a bit?” and then stood up.

Having become concerned about the two, Juan slowly sat down again. Watching him, the others, too, sat down with puzzled expressions.

Soon after, Suzu came in with Okayo holding her shoulder. She seemed surprised to have everyone’s eyes focused on her, and stepped backwards, stumbled a bit, and then sat down. Completely different from the way she’d appeared the evening before, when she gave Shirō the white spider lily, now she looked timid.

No one spoke. From the back of the room, Yazō could be heard clearing his throat. A few moments later, Shirō sat down with his legs crossed.

“So we meet again.”

He said this in a gentle voice, and Suzu, looking very surprised, said nothing.

“I’ve heard from everyone that you did tremendous work at the Mercy House.”

Suzu looked up at Shirō with expressionless eyes. It was as if she hadn’t understood what he said.

“You’ve been searching all over for the old men and women. You must be exhausted.”

With his neck tilted to the side, Shirō glanced at her and continued:

“They must have cared for you.”

He held her wrist and patted the back of her hand. The young girl looked up in surprise. A tiny ray of light, as thin as the eye of a needle, glimmered from her eyes. It twinkled, and seemed as if a dark storm was gathering behind them.

“You worked hard. You worked so hard picking cranesbill and angelica flowers.”

Suzu shook her head at his remark.

“You know, Maria-sama appreciates your hard work. Look—this is a small reward from her for you. Now, won’t you cheer up, Suzu?”

It didn’t seem like they were having a conversation in a room filled with people. It looked like a gentle scene with an elder brother humoring a sister who couldn’t pull herself out of a bad mood, as if it were taking place on a grassy plain with a breeze blowing, or on a boat in the sun.

From beneath his collar, Shirō removed the rosary that had been hanging from his neck, and hung it around the neck of the young girl. Its small blue beads shone in the light here and there.

Suzu accepted it, and glanced around at the men with a strange expression. Then nervously, she touched the rosary hanging from her neck, and, after noticing Jinsuke, tilted her head to the side. Jinsuke held both of Suzu’s shoulders, turned her around toward Shirō, and spoke in a somewhat choked voice, one word at a time:

“Suzu, this is a reward for Suzu. Maria-sama appreciates your hard work—it’s from her.”

Hearing this, the girl faced her adoptive parent, and held out both of her hands as if asking for help. Deeply moved, Jinsuke embraced her, and started to weep silently.

In silence, the people behind them watched the scene attentively. The man of nearly fifty years and the innocent young girl embraced each other, weeping. Ahh—they all thought—this, too, will help Jinsuke a bit.

A group of people who worked for Jinsuke had come to see off the visitors, and had just happened to witness this scene. Kumagoro thought back on events, Since yesterday morning, unusual things have been happening. There was that strange sunrise. And, just as Suzu announced, a ship with a red flag came, carrying a dazzling-looking man. And, in the midst of the big storm, the grain was delivered. Until that time, that little house was still standing there.

Running up to the door, he had knocked and called, “Hey everyone, the grain’s here. Tomorrow you’ll have some nice porridge. Would you open the door? Open up!”

Answering his shout, the old woman Onatsu called out, “Grain—ah, the grain. Well, thank you. I’d like to open the door, but the wind tonight is strange. We asked for the door to be boarded up. We can’t open it from the inside because it’s nailed from the outside.”

Matsuyoshi and Kumagoro pried the door open. It was a small, unlit room.

“Oh—the grain!”

And as they said this, several of the elderly had crawled toward them and touched them with their warm hands.

“Thank you ever so much. Bringing it—to us, even—all this way, and on a night like this.”

And then the men had left, boarding up the place securely again as they had been asked to do.

“Tomorrow morning, early, we’ll come back and open the door.”

And with those words, they had gone back home.

The voice with the words, “Thank you ever so much—to us, even,” rang in their ears. Taken in by Suzu and Jinsuke’s tears, Kumagoro, too, began to weep.

Silently, on bended knee, Shirō made the sign of the cross on the two people, and then, in a barely audible voice, he began reciting,

“In the name of the Sacrificed One who opened the gates of heaven, grant us strength. Grant us a helping strength. We pray for them for eternal life in heaven. Amen.”

As if suddenly taking notice, Juan brought his hands together and started to chant. After the Oratio was finished, all the men started to pray with their heads bowed, and the women came in from the kitchen and joined them. And so it happened that the house was turned into a place of worship.

Okayo was behind Daisuke. Though everyone felt exhausted from the past night, and they would have been expected to have been hazy and sleepy, Okayo had the strange impression that a pure light was streaming out from their bodies, and from her own body as well. It seemed they were all praying for the sake of the dead, for Suzu’s sake, and for everyone’s sake.

People recalled the scene as they headed back to their homes. In past situations like this, Juan had been given the role of a priest. But on this night, they had the strong impression that they had been led by the voice of the young boy, and that the venerable samurai had humbly followed him. And not only had those present felt that there was nothing strange about this, it was if they had all been joined in rapture.

With everyone wondering and asking who this young person was, and where he had come from, the members of Jinsuke’s family and the Ninagawa family felt proud. Even Juan, who normally maintained an unchanged countenance, smiled and joined in the questioning.

“We’ve found a great brother. With this fine young man, we’ll now be able to pass on Western learning. Perhaps we can’t build a Seminario or a Collegio like the old ones did, but we can call together the people who were connected to those institutes, and we can start a confraria where young people can study. I, too, want to realize this dream—even this once.”

Juan spoke in high spirits and with undaunted expression.

Yazō’s boat was found where it had been pushed up onto the shore near the outlet to the sea, but it was damaged beyond use. In the fields around the bay, there were other boats that had been washed up, along with broken parts and debris. Tatters of clothing could be seen amidst the wreckage. But even after digging through the debris, no more bodies were found. When the main cleanup work had been mostly finished, funeral rites for the dead were carried out on a hill overlooking the sea. Since old Onatsu had been a Buddhist, a Buddhist priest, one from a temple her family had been connected to, was called in, and he recited sutras.

Having a Buddhist priest come presented some trouble, since some of the people said that the funerals should not be held with Buddhist priests, whom the padres had called “devils.” They should be done separately.

At that time, Oume, who normally would never have spoken at such a place, stood up slowly. Wiping her hands on her apron, having just come from the kitchen, she stood in silence for a moment, but then, she turned and faced those who had spoken.

“Excuse me, but— ”

With her swollen eyelids blinking slowly, she began to talk.

“Are you going to leave old Onatsu alone even after her death?”

Her words brought silence to the entire gathering.

“We all know Onatsu was a Buddhist. And so am I.”

Omiyo glanced up anxiously at Jinsuke, and then, looked down. Oume appeared larger than ever.

“As all of you know, when she was young, she went to Nagasaki, and became a prostitute to support her family. When she got older and came back here, she had no family left to look after her. Many times, she used to cry because she didn’t have enough money to pay the temple, where the graves for her ancestors were, to hold memorial services for her parents. She also worried that she would be punished sometime because she had been fortunate enough to receive food, and a place to stay at the house for the elderly, along with the others, even though she was a Buddhist and not a Christian. She confessed these things to me one time.

“She always worried about how she would live. She said she was happy to have been well cared for by the Christians. And so, at this time, are we now going to say we’re going to cut our ties with her, and just get rid of her? I don’t understand what you’re thinking.”

Oume-san, who had spoken so forcefully, turned silent, apparently cooling her heated feelings a bit. And then, slowly, she looked up, gazed around, and in a lowered voice, continued:

“I, too, have a different religion. But I respect the okite that you observe, about caring for neighbors. “Care for your neighbors as you would for yourself”—that’s what I am aiming for in my life. On this point, there is no difference in our beliefs. That is the way of people. That’s what my parents taught me, and that’s why I’m saying this now. We must treat all people as being just as important as our own selves. Now, as for Onatsu-sama, this talk of holding her funeral in a separate place—it is something I just cannot understand. Those who had no relatives were living together there, and died together on the same day . . . Is it all right for Christians who say “Amen” to suggest such a thing? Would you feel good about throwing someone down into the Inferno? Has our spirit of mercy been washed away along with that flood?”

With her body shaking, Oume drew her bony wrist from the opening in the sleeve of her kimono, wiped away her tears, and clutched her apron.

Jinsuke and Daisuke both thought, “Now she’s said it. Oume-san’s done it. Oume, the Buddhist, has gotten us to straighten things out.”

The murmuring and commotion subsided like the ebbing of the tide. From then on, serious discussions proceeded unhindered.

They spoke of many things. Funerals are held for comforting the souls of the dead. They would hold all the funerals beneath the big camphor tree at the top of the hill, facing the sea. Thinking about the spirits of old Onatsu’s ancestors, they would have a priest from her family’s temple come and recite sutras for her. Even if the ties had grown weak, in the old days, her people had been connected to the temple there. After that, they would recite prayers from their own faith.

Beneath the great camphor tree at the top of the hill—that will truly be a good place. From there, you can see the ocean all around. It’s the right place for calling out to the souls of the dead. And—that’s right—that’s the tree where all the young children have always come, climbing up and down, cooling off under its shade and having their lunches, where they’ve always looked for boats out at sea and chatted together. The old folks from the Mercy House who died will be facing the sea and talking, and the young folks will be running all around—why, it will be in the very sight of heaven.

As they talked on, the bitter edge of the earlier discussions wore off. The talk about the old folks had created an image of making a heaven on earth. It was wonderful to see how it brought peace to their hearts. Okayo, nodding from time to time without softening the serious expression on her face as she watched Oume-san, wanted to talk about something with Daisuke. But noticing the strained expression on his face, she decided to wait until later.

About the time when the commotion over the typhoon was settling down, she realized that she had become pregnant. For some reason, when she first felt the movement of the baby in her body, the thought of Oume-san’s solemn face came powerfully to mind. And at the same time, the image of the great camphor tree at the top of the hill after the funeral, with no one there, flickered through her thoughts.

Okayo could read simple characters written in hiragana lettering, but she couldn’t read Chinese characters like her father-in-law and Daisuke. Oume could understand even fewer of the Chinese characters. What, Okayo wondered, was the history of that great camphor tree? Had the tree’s history been written down in words? Didn’t that tree and Oume have some connection to each other? And, it seemed to her: I’ve known about that big tree, and about Oume-san from way back, even before I was born. She wondered how Daisuke would respond if she spoke of such things to him.

Okayo spoke about the great tree to the child in her womb. She saw the image of the tree in her dreams. Its top branches, drawing in the rays of sunlight from across the sea, murmured gently, while white clouds came and went above them. Beneath the tree, Oume, her eyes squinting in the sunlight as she gazed out over the sea, was cradling a baby in her arms and playing with it. It was the baby that she, Okayo, had birthed. When she awoke from her dream, she told Daisuke about it.

“Your dream, it seems it was a pretty deep one. It must have been a blessing from God. And the baby—did it look like me?”

“Well, I can’t really say if it looked like you. It was a baby . . . I can’t really tell.”

“Really? Was it that unclear?”

“I would say that Deus-sama and Kirisuto-sama are the most revered beings in the world—but that big camphor tree is a special case. It seems to me it might be a god.”

“Well . . . that tree certainly is something special.”

“It seems to me it wasn’t Deus-sama; it was that camphor tree that showed me our unborn baby, and yet . . . I can’t say who it looked like. But it sure was an adorable baby.”

“ I envy you—having such a nice dream.”

Probably, Okayo had wanted to say something more about her dream’s connections to the deeper world of things, but their conversation ended there.

A rumor that the verdict from the governor’s office might be eased had spread among the farm workers. Daisuke mentioned to his father that Kumagoro had come in with such news.

“No—it’s not going to happen. Though we want it to get easier, it’s just not going to happen.”

With a pained look, Jinsuke spoke to Matsukichi and Kumagoro.

“We can’t take it easy just from hearing a rumor like that. Once we find out the truth, things are going to feel even tougher.”

The rumor had been brought in by Sadaichi, a friend of Kumagoro. Sadaichi’s voice was animated when he rushed in for shelter from the rain.

“Those officials, they aren’t completely blind. If they just take a look at all the rubble and damage around here, surely they’ll see, won’t they?”

“Right. If they just look at the ruins of what used to be fields—even fools like us can understand.”

“We have the eyes of moles, but when the officials look with their eyes, can we really expect them to see? What do you say, Kumagoro?”

That wasn’t just Sadaichi’s hope. Matsukichi and Kumagoro had also heard rumors when they were going all over the area, repairing roadways and clearing fallen trees. But no matter what people’s hopes were, they had to face reality. People hoped that, for once, the officials would hold off on the land taxes this year, and give them some rice assistance. And so, hopes had led to rumors that the governor would actually do such a thing.

“But look, just hoping for things like this, we can’t really expect things will go our way, can we?”

While Matsukichi spoke, his voice unmixed with emotion, Oume nodded.

“We might have expected such things with the former lord, but this one, he won’t do it. When we think of what he’s done, we can’t expect much good.”

While this exchange was going on, Oume was thinking about teaching Okayo and Suzu how to soak and flavor the wild verbena leaves that she had boiled and dried.

Jinsuke often accompanied Daisuke on his rounds, doing things like visiting the Ninagawa family and the neighboring Minami Arima village. When they went to Minami Arima, they would row there in Matsukichi’s boat. At those times, Jinsuke would talk to Daisuke, whose face had become well-defined and manly. Both Omiyo and Okayo found this closer relation between father and son reassuring, yet they also felt as if something was pressing on the men.

From time to time, Daisuke reminisced.

“These days, I’ve been thinking a lot about the teachings of our Lord—about taking care of our neighbors.”

“So have I. And you’ve become a lot more important than before.”

“Well, please don’t talk like that in front of other people.”

“What’s wrong with it? You’re not the only one. Since these things have happened, my parents-in-law, Oume, and everyone else have become more important. And they seem more thoughtful. We may die soon, you know.”

“You tend to jump from one extreme to another.”

“What I’m saying isn’t extreme. If we don’t care for other people, we can’t go on living. That’s what “important” means, don’t you think?”

Impressed by what Okayo had been saying, he gazed at her face. He realized that, in an instant, Okayo had understood the true meaning of Ninagawa Ukon’s lectures on the Doctrina Christiana. Or, even more so, she had understood it when she was watching and listening to the words of Oume-san.

“These days, Suzu has often been sitting beside father-in-law, rubbing his back.”

“Yes, that’s right.”

Daisuke spoke out in a somewhat embarrassed voice.

“Come to think of it, these days, I often hear people calling out to Suzu.”

“Right. Suzu’s gotten a lot stronger because of it.”

“If you ask Suzu about her work these days, she’ll say she’s become Oume’s apprentice.”

“Ah, so that’s why she’s been going out, picking mugwort and verbena lately.”

“Right . . . both of those plants are past their peak, and they’re starting to dry out.”

Doctors would come from Amakusa to buy mugwort moxa from Oume; they said hers was easy to use. They said it crumbled beautifully and curled up nicely into balls when they used it. And it didn’t leave burns on the patients when used in moxa treatment.

Oume told Suzu, “Even after all these old folks are gone, there will still be no lack of patients. If we make moxa, it will help others.”

Oume, of course, had been taking the moxa to those who could not see a doctor, and she made her rounds everywhere. She said, “When I crumble the mugwort to make moxa, I recite Namu Amida butsu, Namu Amida butsu. Then, one by one, the spirit of Amida-sama will burn in each of the moxa preparations, and soon, you’ll be well again.”

Suzu’s eyes opened wide, but when Oume saw her face, she smiled with happiness. Then, she lowered her voice and continued:

“But Suzu, if you prefer, it will be all right if you say Amen. I wonder what Deus-sama thinks about me being your teacher. But surely, He won’t cause any problems for the patients.”

Already it was harvest time, but the storm had damaged things considerably, and they hadn’t recovered well. Nevertheless, there were some little places that had escaped the damage of the winds and water, where they could still gather some millet, buckwheat, and other grasses and wild grains. People talked with envy about the wild rice in the few lucky fields. Though the wild rice ears, with their small grains, had fallen onto the ground, people had been able to go out and gather them. They realized it was a meager harvest, and it would not be enough to carry them through until the next year. They wondered how they would deal with the scarcity they faced and survive.

It was decided that they would hold a meeting at Yazō’s house, where they would tell everyone in town about the decree from the governor’s office the other day, discuss how they could work together, and decide what action to take.

“I’m usually away from my house, so when folks ask for me, I’m always a bad host. But this time, since I need to spend some time here working on my boat, let me invite everyone to my place. Whether they come by sea or land, I’ll have some young men welcome them.”

Yazō had already been thinking about how he might deal with the shortage of food and provisions. In carrying out his responsibilities, it was essential that he have the understanding of everyone in his household. And for that purpose, holding the meeting at his place would be the quickest way. And now, during the break times in the discussions, he could provide a little food to warm their bellies. These were his plans.

When people heard of this, they thought, Well, people in the samurai class have their big houses, but everyone feels easy about going to Yazō’s house—it has a kitchen that’s easy for the women to work in, and even if the meeting is a hard one, at least we’ll be able to feel at ease.

On the night of the meeting, there were more people present than expected. The smell of boiling water mixed with smoke filled the room. And then, as people were starting to relax—after having arrived so tired—Yozaemon, one of the leading farmers, made his late appearance, accompanied by his son. His face looked unusually dark. Greeting him just with his eyes, Yazō wondered what to say. He had heard that Yozaemon’s fields had been ruined, but he hadn’t yet been able to pay him a visit. Then Ninagawa Sakyō stood up.

“In the midst of all the trouble that’s been going on, it’s great that all of you could join us. We’re going to have to make all sorts of plans, but first, we need to hear from all of you what the situation is in the villages.”

The heads of all the villages—Kushiyama, Ariie, Minami Arima, Kita Arima, Katsusa, and the others—all stood up, one by one, and reported on what was happening in their areas. Their reports were rather different from the actual state of things. The leaders mostly just reported on what they had learned by going around and talking with people. They all agreed that things were getting more serious day by day, and that the real extent of the damage would only be known later.

As they heard more reports, the genial mood began to fade, and groans slipped out here and there. Once they had been told about the general state of things, Jinsuke, noticing that the meeting had grown silent, stood up and began, in a restrained voice, to recount what had happened at the governor’s place the day before the typhoon. Perhaps because he was trying so hard to control himself, his voice sputtered from time to time, and he almost lost the thread of the story, but everyone was drawn into each of his words and listened intently.

After Jinsuke sat down, no one spoke for a while. The silence was broken by the summer screeching of cats, which was much more noticeable than usual. The white-haired Juan stood up with his rosary in his hands.

“Well, it looks like we’ve finally reached the moment of truth where we’ll live or die. We have to gather our courage, make up our minds, and get things in order. And then, we have to choose people to represent us and make good plans.”

For a while, people separated into groups of their own village members, and held discussions. No matter what happened, they needed to inform the governor’s office of their situation as clearly as possible. The government had to redress the unfair land taxes that had been imposed on them for many years now, and unless they were given an extension for the payment of taxes, the villages could not survive. If the officials would just look at the destroyed houses and the washed out, rubble-strewn farmlands, surely even they would realize that the situation was unjust and inhumane. Before they received any strange summons, the people would write petitions and sign a joint statement.

Ukon had remained quiet at the back of the meeting, but presently, he was called on to assist with the writing, together with Daisuke.

It was decided that separate statements should be written from each area, and then, they would take them all to the local government office, and present them on the same day. The statements would describe the conditions of the local areas, and they would call for agreement on two points: reduction of and exemption from the land taxes for this year, and emergency allotments of rice.

At that point, a man stood up. It was Isayama Chūbei from Kita Arima village, whose hair was flecked with white.

“After the storm, did any anyone from the government offices come around to check on the villages?”

“Well . . .”

Both Sakyō and Jinsuke spoke up together, but it was Sakyō who continued.

“It’s strange we haven’t heard anything from them.”

In the group from Arima village, there were quite a few samurai, and having them there, remaining silent with their arms folded, created a rather oppressive atmosphere.