2018 Kyoko Selden Translation Prize Announcement

On the fifth anniversary of the establishment of the Kyoko Selden Memorial Translation Prize through the generosity of her colleagues, students, and friends, the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University is pleased to announce the winners of the 2018 Prize.

In the category of “Already Published Translator,” the prize has been awarded to Dawn Lawson (Head, Asia Library, University of Michigan), for Nakajima Shōen’s A Famous Flower in Mountain Seclusion (Sankan no meika, 1889). Lawson’s translation makes available in English for the first time a full translation of the novella by the woman who, under the name Kishida Toshiko, was a powerful orator of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement and a key figure in early struggles for women’s rights in Japan. The translation renders into delightfully readable English Nakajima’s witty satire of Meiji mores, as well as her depiction of the isolation often endured by women who, like herself, pursued lives that did not entirely conform to patriarchal norms.

This and other prize-winning translations will appear in the Asia-Pacific Journal.

***

Introduction

Nakajima Shōen (1861-1901), also known as Kishida Toshiko, was the leading woman orator of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement (Jiyū Minken Undō). On October 12, 1883, after addressing an audience in Ōtsu on the topic of “daughters in boxes” (hakoiri musume), she became the first woman charged with the crimes of “political speech without a permit” and “insulting a government official,” for which she spent eight days in jail and was assessed a substantial fine. Her essay “To My Fellow Sisters” (“Dōhō shimai ni tsugu”), published the following year, is a key document of the initial stages of Japanese women’s struggle for equal rights. During her tuberculosis-shortened life, Shōen also had a dynamic teaching career, was wife to a politician-turned-diplomat and stepmother to his three children, composed many Chinese poems, and published several works of fiction, including Sankan no meika, the autobiographical novella translated here as A Famous Flower in Mountain Seclusion. This text is of interest for many reasons, not least because of its portrayal of a character who, like Shōen, had withdrawn from public life while her husband and even her own followers remained politically active.

Sankan no meika was published in serial form in the literary journal Miyako no hana between February and May of 1889, with two chapters each appearing in five issues. In this work Shōen depicts three marriages: one based on her own “love marriage,” in which the partners chose one another freely; that of a former geisha whose contract her philandering husband purchased after the death of his first wife; and that of a well-educated woman who impulsively made her own choice as a lesser evil compared to the matches her family was pushing. We are able to observe these marriages directly, through dialogues between the spouses, and indirectly, via narratorial asides and discussions of the couples by other characters. In addition to this multidimensional treatment of marriage, Shōen brings in the issue of how political causes can best be advanced—by both men and women. Her skillful intertwining of these themes makes Sankan no meika a truly remarkable text.

The closest work to Sankan no meika in terms of time and subject matter is Miyake Kaho’s (1868-1944) Yabu no uguisu, which was published less than one year earlier, in June 1888, and is widely considered to be the first modern Japanese novel produced by a woman. Written at nearly the same moment in Japanese literary history, Yabu no uguisu and Sankan no meika naturally have some similarities in terms of both style and subject matter. Both use multiple perspectives and include dialogues marked as they would be in a playscript. The issues treated by both works include the Japanese adoption of Western-style balls and dress, women’s education, marriage, corrupt bureaucrats, and economic hardship. Central to both are the closely related questions of what kind of life a woman can have and what kind of marriage she can make in Meiji Japan. The titles of the two works are similar, too, connoting the setting apart (in the bush or in the mountains) of a gifted or special individual (a warbler or a famous flower). These allusions to the fact that their works feature characters whose actions set them apart from ordinary women, of course, can be applied to the authors themselves as well.

Despite these similarities, the two works have quite different flavors. Reflecting its author, Sankan no meika is bolder and more radical. It calls into question many aspects of Meiji society, beginning in the first chapter, in which the protagonist, Takazono Yoshiko, criticizes the adoption of Western-style balls as a means of forcing men and women to interact. It challenges the use of servants by having Yoshiko perform the hosting duties when a group of men come to talk politics with her husband. After she has served them, she remains in the room, an action that is shown to make them very ill at ease. When her own former students visit, concerned that the world is criticizing their teacher for compromising her principles by getting married and withdrawing from public life, she explains to them that the time for action by “extraordinary” women has passed; now all women must gain access to education and become able to raise their status themselves. Her engagement with issues like these make Sankan no meika an extraordinary work, but it is all the richer because Shōen does not restrict her attention to women and marriage. She also shows, for example, the protagonist’s husband counseling male activists and contemplating how to position himself in the political landscape. She even manages to inject a bit of satire along the way.

Sankan no meika features the stylistic diversity typical of its time. Most chapters open, as does the first one, with a highly Sinicized description of their setting. In addition, much of the work consists of dialogues between characters from a variety of stations in life, ranging from the gossip of lowly servants about their master to intellectual exchanges between the protagonist and her husband. Chinese poems composed by Yoshiko to assuage her loneliness when her husband is away are included in the text, as is the transcription of a newspaper article. Attempting to render in English these many shifts in voice and style made this work both challenging and rewarding to translate.

***

Chapter 1

A host of peach and plum blossoms reflected in silvery candlelight

In his “Ode to Epang Palace,” Du Mu described a scene in which the sunlight that had warmed the dancers on a stage gave way to cold wind and rain buffeting their sleeves. Here at the famous Gathering of Beauties Pavilion, the women are as beautiful as blossoms, and with their every step a breeze wafts up around the high tower, scattering a floral fragrance. When they stand still, gazing coquettishly into the distance, images of spring reflected by the silver candelabras are inscribed on the walls. The sound of rickshaws echoes in the distance, while laughter bubbles up nearby. For drinking there are beautiful goblets; for dancing, a jeweled platform; for conversing, beautiful women and talented men. In the interest of making themselves as lovely as possible, these people can easily spend hundreds of gold pieces on a single ring.

“Outside the temple gate, it is really Japan: The tea leaf pickers are singing,” a haiku poet wrote upon returning home from the Obaku region of Uji, where she had seen architecture so Chinese in style that it was as if she had left the country.1 Likewise, a person who joins in the festivities at the Gathering of Beauties Pavilion ends up thinking only of the finest vessels, jewels, gold nuggets, and gems. A widow crying out in hunger, an orphan suffering in the cold, an invalid with the tax collector outside his gate, a family torn asunder by a year of misfortunes—pitiful stories like these take place far below, and those who walk on clouds hardly dare sympathize with such beings lest the atmosphere be tainted by them. People who have eyes only for the pleasures of this world envy the occupants of this most delightful separate heaven. Like beautiful flowers—pale cherry blossoms, deep plum blossoms, white roses, and red crabapple—dressed up for an intimate, convivial gathering in a vase, seven or eight women talk in one corner of the tower, their voices rising and falling with the waves of the conversation. Suddenly someone says, “Well, my goodness! Look over there, everyone, that’s Mrs. Takazono—Yoshiko—is it not?” prompting the cool reply, “No. What would she be doing in a place like this?”

“Look again. Doesn’t she look like Yoshiko from the back? Shall I try calling her?”

“Well, wait a moment. She should be coming over here anyway. . .But if it is Yoshiko, it’s really strange. Why? Because Yoshiko is a woman with a reputation for absolutely hating balls and Western-style dress.”

“But you never know. We said all kinds of things in the beginning, too, didn’t we, Otsuta?”

“Look! Here she comes. What are we going to do? It is Yoshiko. Her outfit is unbecoming, as you’d expect of someone who hates Western clothes.”

“Be quiet. She’ll hear you.”

“But isn’t it a bit much—her coming to an event like this dressed like a country bumpkin? Isn’t there such a thing as spoiling the dignity of this building?”

The women, whose attractiveness didn’t go beyond their faces, did what women have a habit of doing when they get together, which is to judge other people’s appearances and say nasty things about them. It might sound like an overstatement to say that hearing someone praised was almost as horrible for them as hearing of a dear friend’s death, and that hearing someone criticized was so amusing that it made them forget their aches and pains, but doesn’t it seem a bit like that? Takazono Yoshiko and several other women walked toward the group. “Oh, it’s Torisu Oyu, and Otsuta is here, too,” Yoshiko began, but without waiting for her to finish her greeting, Oyu half-smiled and said, “Otsuta and I were just talking about you, squabbling about whether it was you or not. . .What a beautiful outfit! And the way the ribbons decorate it is splendid, don’t you agree, Otsuta?”

“Absolutely. Western-style clothes are definitely right for Yoshiko.”

“No, I’m not used to them. Do I really look all right?”

“You look marvelous.”

The lengths that each went to in an effort to surpass the others in flattering Yoshiko—and the contrast with how they had been talking earlier—was truly amusing. Yoshiko smiled and said, “There are a number of you I’ve never met before. I’m Yoshiko, Takazono Kan’ichi’s wife. Please don’t let me interrupt you.”

Ever more gleeful, Oyu said, “Yoshiko, we’d be really pleased if you’d keep attending balls from now on.”

Yoshiko: “I’m not used to them, so I’ll need all of you to teach me what to do and let me into your group.”2

Oyu: “We’ll be a nuisance for you, I imagine, but please. . .It’s just that you’re so beautiful—no matter how much we dress up, all eyes will always be on you. We’ll be exactly like withering trees in a garden—no one will tie a strip of paper to us.”3

Yoshiko appeared annoyed by Oyu’s words, but Oyu didn’t notice at all. “Yoshiko, I heard that you had a strong dislike of Western-style clothes, balls, and the like.”

Yoshiko: “I didn’t say I absolutely hated balls. They make the world beautiful and give pleasure to people, so I guess they are something we should have. But I think it’s extreme when the people who like balls say that men and women wouldn’t socialize if there were no balls, or that they can’t socialize without them, or that if they do it’s boring. Apparently balls are all the rage in the West, where the countries are said to be civilized or something, but I think that when we take another step out of the mud into civilization, this trend will change. After all, the main reason this kind of entertainment became a method of socializing is because there are too few pleasures shared by men and women.”

Otsuta: “That couldn’t ever change, could it?”

Yoshiko: “But old women can only talk with other old women, and children with other children. Otherwise, it’s no fun because their interests aren’t compatible, right?”

Oyu: “That’s right.”

Yoshiko: “You see? In my opinion, saying that men and women can’t socialize without balls is similar to saying that when adults try to play with children, they have to play games that the children are able to play. . .Wouldn’t it be pleasant if we each had more interesting things to talk about with our husbands?”

Otsuta: “No, that can’t happen. Men and women can’t feel at ease if they don’t dance.”

Yoshiko: “Really?” The surprise in her voice was palpable.

Oyu: “Yoshiko, is something wrong? I don’t like it when you don’t answer.”

Yoshiko: “What? I’m sorry. Did you say something to me?”

Oyu: “And they say that dancing is good for one’s health.”

Yoshiko: “I’m sure it’s a good thing, but if all you do is sit around in the same room all day, except for once or twice a month, when you dance. . .”

Otsuta spoke before she was finished. “Putting that aside, what are your thoughts on clothes?”

Yoshiko: “Clothes should be Western-style.”

Oyu: “Really? But you. . .”

Yoshiko: “Yes, and I think that if Japanese clothes are to be improved, they should be replaced with pure Western-style clothes, not a combination of Chinese, Japanese, and Western-style clothes. Some may say that these days people have gone too far in adopting Western-style clothes, which look ugly on them because they don’t suit them, and that they should wear the clothes that Japanese people have always worn, otherwise Western people will laugh, but. . .”

Otsuta: “Is that true?”

Yoshiko: “People say all kinds of things. It isn’t just clothes. There are many things to be laughed at, but we can’t do anything about that.”

Oyu: “Why not?”

Yoshiko: “Because as it stands now, they think they’re better than we are.”

Oyu: “So you are really in favor of Western-style clothes, Yoshiko?”

Yoshiko: “Yes, I am. But people vary in terms of what they can afford, so if someone who usually can only wear an inexpensive double-striped kimono feels that they have to change to Western-style clothes and has a Western-style outfit made this month that renders them unable to buy rice and pay the maid—I mean, I doubt that this would happen, but one hears all manner of rumors. . .One time Mrs. Hayatake of the Women’s Improvement Association came to see me, and she started saying that I hated Western-style clothes based on a misunderstanding of a casual remark of mine. And it seems like the way I’ve been talking now might start a rumor that Yoshiko likes cotton and hates silk, but I only want our homes and our clothing to be beautiful. I don’t think we should let things get out of balance as we make progress. . . It seems like all I’m doing tonight is making excuses.”

“So that’s how you feel, Yoshiko? It’s really troubling how strange rumors get started.” Oyu and Otsuta spoke in unison.

Chapter 2

Dimples, which can kill people like knives, are to be feared

Like the priests who resent the crows because for making messes on the temple grounds, it is for the most part understandable that servants and maids speak ill of the people who use them, their masters. Given the position they are in, it is quite natural. Standing next to the kitchen brazier, one maid gathers up the unruly strands of hair hanging down her neck and says to the other, “Otake, it’s unbearably cold tonight. . .Let’s build as big a fire as we can. Otake, won’t you come sit over here?”

“Won’t I get in trouble if I don’t work all night?”

“You haven’t been at this mansion long enough to know, but you can’t just be meek all the time. . .You’d be surprised about servants. . .When I lived at home, my mother was a noisy old bag. She complained 365 days a year, saying things like, ‘There’s nothing as burdensome as a daughter; if only you’d been a son. Here it is, time for you to be taking care of your parent, but instead you are costing me a fortune. All you do is sit in front of the mirror all day, even though you are a homely woman.’ But I gave as good as I got.”

Take: “Oh, my. What would you say?”

Tora: “I’d say, ‘If I’m homely, what about the person who gave birth to me? . . . From night till morning, morning till night, all you do is use me to do the laundry and scrub the bottom of the pots. Have you ever given me a single thing? Think about it! What with all I do, I’m surprised that you can call me a burden.’ . . . If someone is going to complain about you all the time, it’s much easier to be a servant. All you have to do is flatter your master a little bit, and it’s ‘Here, help yourself to this collar,’ and ‘There, take that apron.’ Soon you need a whole extra wicker trunk for your new belongings. I say that, but now I’ve had it with being a servant. . .But it depends on the mistress. This mistress and her family here seem to think that they can make unlimited use of their servants . . .They fuss about happily when they are going to a banquet or a ball, but those are the days that are bad ones for the servants. It’s ‘Bathe me, wash my hair, put on my powder,’ and they can’t even reach things that are right in front of them. . .Otake, do you know about the mistress’ past?”

Take: “No. But she is very pretty.”

Tora: “She should be. Now they call her Countess, or Lady, or Mistress, but until three years ago she was Kotsune of the pleasure quarters. . .”

Take: “If that’s true, she’s really come up in the world. . .Hasn’t she?”

“She killed the previous mistress,” Tora whispered.

Shocked, Take said, “That beautiful woman killed someone? With a razor? A knife? A gun? A sword? With what?”

Tora: “With nothing. Except her dimples.”

Take: “I don’t know what you mean. Hurry up and tell me.”

Tora: “Oh, it looks like the lamp is going to go out. I guess there’s wind coming from somewhere. Yes, yes, it was almost four years ago.”

Take: “What was four years ago? . . .”

Tora: “It was a cold night exactly like tonight. I heard the sound of hands clapping inside, and when I went in, I saw the previous mistress.”

Take: “And?”

Tora: “I’d heard that she was the daughter of a prominent samurai family. She was sitting in the shadow of a dim lamp darning the master’s socks, and she said, ‘Is that you, Tora? You’re up late night after night—you must be so tired. We can sleep late in the morning, but. . . I think the clock just struck twelve. The later it gets, the colder it seems. As long as there is boiling water for tea when the master gets home, you can tell everyone to go to sleep. Please, you get some sleep, too.’

I felt so sorry for her then. I calmed my racing heart and said, ‘I’m sorry. Servants’ bodies get tired, but they don’t have any troubles weighing on their minds. There must be something bothering you. The master doesn’t like to see you sewing, so he wouldn’t understand that because you do so on cold winter nights like this, he is better dressed from head to toe than anyone in the crowds of people who come here as guests. . . Mistress, should I put something warm in your bedding? The master probably won’t come home tonight either, so why don’t you go on to bed?’ I said, and when I looked up at the mistress. . . she was tearing up and unable to speak. . . I said, ‘I’m sorry. I left the sliding doors open and made you cold. If you need me at any time, just clap your hands. . . Good night.’ I went into the kitchen. . . Later I heard that her husband had become infatuated with our current mistress at that time, and the former mistress died after contracting tuberculosis from worrying about it.”

The pair spoke in unison. “Someone’s clapping again. They probably want the tobacco tray lit, even though the brazier is right there next to it. Clap, clap. We hear you.”

If you’re wondering whose house this is, it belongs to Torisu Tamotsu, and it has a variety of perfectly furnished rooms with appropriate designations, such as the chair room, the folding screen room, the mirror room, the tea chest room, and the makeup room. The timeless decorations in each room are such as you won’t even see among the rare treasures in a temple—things that are boasted to be from the altar of this or that lord or noble—all out of keeping with the amount of money that the master earns each month in salary.

Tamotsu’s present wife, Oyu, tired from a ball the night before, finally rouses herself sometime after ten in the morning. Without bothering to wash, she puts a black silk crepe jacket with one small crest on it over her nightgown. Her face is pale, and her bangs almost cover her eyes. As she sits leaning against the brazier, one knee bent upward, lighting a pipe, her elegant, sensuous allure—far more enticing than the trembling flirtatiousness of a white garden rose weighed down by rain—might have evoked feelings of love.

Oyu: “Take, is that you over there? My office-hating husband left for work unusually early this morning, but is Tatsu (his chauffeur) back yet?”

Take: “Yes, a little while ago.”

Oyu: “Humpf. He should have told me he was home. . .Ask him if they went straight to the office.”

Take: “Tatsu always says, ‘The master’s side trips are off-limits’ and won’t answer.”

Oyu: “What? If that’s the case, never mind. I’ll ask him myself. I don’t need anything from you right now.” Her haughty expression complemented her maid’s sullen one.

Oyu’s mother, who had come to live with them two or three months before, now had everything she needed for a comfortable retirement. She addressed her daughter.

“Oyu, you don’t need to worry so much. . . Do you? Did you have a good time last night?”

Oyu: “I really did. I haven’t told you about last night yet. Someone quite unexpected turned up.”

Mother: “Who?”

Oyu: “Mr. and Mrs. Takazono.”

Mother: “Humpf. The world really is in flower, isn’t it?”

Oyu: “That Mr. Takazono is elegant and formal, perfect. . .When I was in the trade, the fact that a man was stylish and parted with his money readily was all that mattered to me, but now that I am living respectably and have my own household, it’s just the opposite. Even if he’s not stylish, it’s most important that a husband is appropriately serious, consults with you on domestic matters, and makes you feel secure. My husband says the first thing that comes into his mind, and when we go to balls, as soon as he sees a pretty wife or an unmarried girl he flatters them, laughing even when nothing is funny. I don’t know whether to call him a fool or what. But if I start to talk to another man, he says right away that I’m flirting. I regret not having married someone like Mr. Takazono.”

Mother: “But you can’t do anything about that. . .A man like Mr. Takazono wouldn’t have come to the quarters to begin with, so there’s no way you could have met him. Only a playboy takes a geisha for his wife. So the wife has to act accordingly.”

Oyu: “If you say so. You’re right.”

Mother: “What’s important for you is to stop crying over spilled milk and be prepared to be divorced at any moment. We discussed the public bond certificate at some point, didn’t we?”

Oyu: “It has already been changed to be in my name. The land in the country is mine, too. . .He still has a lot of gold coins left, and he won’t give them to me. . .When he first got me out, he did anything I asked, but that’s not the case now. The way he acts now, he may have something on the side. . .’

Mother: “You should definitely take everything you can get. But as long as you have that bond certificate, you’ll be all right no matter when he divorces you. That would be. . .”

Oyu: “Of course, that would be better.”

After that, their conversation gradually faded out, and all was still within those four walls, except for the sound of the tea kettle boiling.

Alas, men of the world. If you take a woman like that for your wife, how will there be any pleasure in your home? The life of a couple like that is as if they are climbing a steep rocky road their whole lives—while they’re walking they’re hot, while they’re resting they’re cold, and they are ultimately unable to find the emotion known as tenderness, which is sweeter than honey and softer than cotton. They feel only obligation and pain. It is a pity, because we all know it is the result of not being cautious at the outset.

Surprised by the sound of footsteps in the next room while she was having this confidential talk with her mother, Oyu asked brusquely, “Who’s there?”

“There’s someone here to see the master.” The maid approached her with a card. “They’re asking if he is at home.”

“Who can it be?” Oyu said, reaching for the card. The maid realized immediately that her mistress couldn’t discern anything other than the fact that there were four square characters on it.

Maid: “It’s someone who hasn’t come much lately, but during the former mistress’. . .”

Oyu: “What? What’s this about the former mistress?”

Maid: “I believe it’s Mr. Takazono.”

Oyu: “You don’t need to say that. It’s on the card. . . Show him into the sitting room.”

Maid: “But he said ‘If the master is at home.’”

Oyu: “It’s all right.”

Because he was shown in, Takazono Kan’ichi assumed that the master was at home. He sat down and waited and waited, but the master didn’t appear. Kan’ichi privately concluded that government employees were indeed arrogant. While he was muttering to himself that it was no surprise that they had a bad reputation with the public, someone finally entered the room, but it was Tamotsu’s wife, Oyu. Kan’ichi intended to ask about Tamotsu right away, but first they exchanged pleasantries about the night before, and then the small talk continued, as if she intentionally wanted to prevent him from asking about her husband. He felt uncomfortable and was waiting for a break in the conversation when the maid, having brought someone in, spoke from the next room.

Maid: “Madam, there’s someone here to see you.”

Oyu: “Hello, Otsuta. Come on in . . .It’s good. . .” Kan’ichi took this opportunity to break in. “I’m in a bit of a hurry today. Is something keeping your husband? I’m sorry to bother him, but I wanted to ask. . .”

Oyu: “Unfortunately my husband isn’t home from the office yet. But he may be home soon. Can’t you stay, even if he isn’t here? Take, bring us some sweets.”

Kan’ichi: “Your husband isn’t home? If I had been told sooner. . .I’m sorry to have bothered you.” Kan’ichi pretended not to hear her suggestion that he stay, and the expression on his face as he left was one of displeasure.

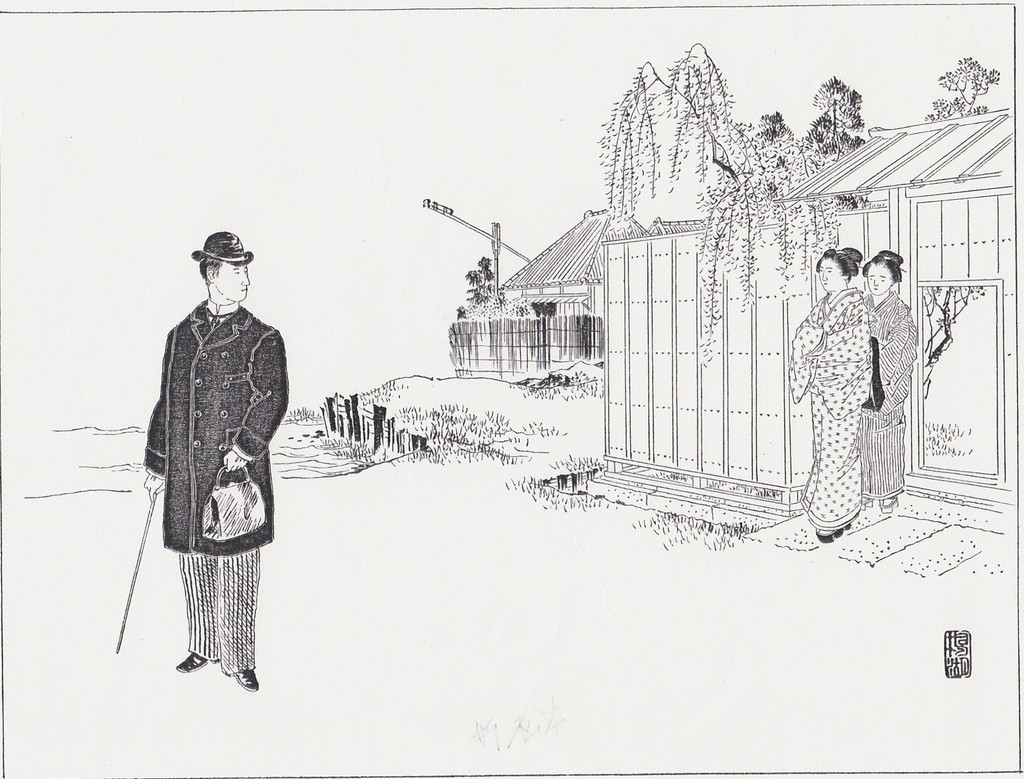

|

Illustration by Matsumoto Fūko |

Otsuta waited for Oyu to return from seeing him off and then said, “Hello. Thank you for last night. . .What did Mr. Takazono want?”

Oyu: “I don’t know why he came here.”

Otsuta: “You’d think that if your husband wasn’t here he could speak to you.”

Oyu: “If you hadn’t turned up, he might have stayed longer.”

Otsuta: “You’re blaming me. . .”

Oyu: “What? It’s not that, but he certainly is charming.”

Otsuta: “I wouldn’t want to be his wife. He scowls whenever he sees a woman. . .But they say he’s nice to his wife. . .Last night you couldn’t keep your eyes off him, ha ha. Madam, won’t you have a new Western-style outfit made?”

Oyu: “That’s just it. I talked to Tamotsu about it last night when we got home. . .He said we’d have some money coming in soon.”

Otsuta: “Aren’t officials confined to their monthly salary?”

Oyu: “There are enough side jobs. If it weren’t for those, I wouldn’t be able to order any clothes.”

Otsuta: “Oh, is that so?”

Chapter 3

Patriots hear the heart-rending sound of a flute when day breaks after a night in which their faithful wives have been chanting their longing for them to the moon

Puffing on a cigarette, Torisu Tamotsu thought, “Considering the status I used to have, I’ve really come up in the world. Before the Restoration, when loyalist samurai were staging uprisings all over, well, it wasn’t exactly the stuff of the chronicles of the rise and fall of the Minamoto and Taira. But it does bring to mind the lament of Third Lieutenant Taira no Koremori’s wife when she took hold of his armored sleeve and tried to prevent his departure. ‘Don’t leave me alone in the capital—what will I do? You shrug me off so coldly. Look at me! I would accompany you as far as the most distant field and into the deepest mountains. No matter what unaccustomed hardships travel might bring, they would be preferable to being abandoned to spend my days and nights pining away with no end in sight.’ Receiving the traditional cup of parting water from his beloved wife as she laments, he can barely manage to swallow through his own tears. He knows that this may be their last meeting and that it is vain even to wish that they might see each other again.”

Many of Tamotsu’s comrades ended up like the Taira, as corpses on a battlefield, exposed to the elements, but not he, for better or worse. Tamotsu was born a younger son, which was tantamount to having the characters meaning “cold rice” stamped on one’s forehead. He had to fill his belly with potatoes and radishes and wasn’t even given enough change to go to the public bath. A break came just when he was hoping for one. He knew that it was his best opportunity, and there was nobody to stop him. Partly out of curiosity he left home and plunged himself into the midst of the patriots. When there was wild merrymaking and heavy drinking, he made sure that no one indulged more than he did. He adroitly managed to avoid involvement in anything life-threatening, and when things finally settled down and it was time for the spoils to be distributed, he couldn’t help admiring himself for the elegance with which he donned the skin of a patriot and made his way to the head of the line. “I was really a smooth operator,” he thought. . . Many of those who had survived by exerting themselves in all directions on behalf of their country didn’t even have heating fuel for their stoves in the winter—they had to crowd around a charcoal brazier in threes and fours with their families, passing the time exchanging stories of their trials and tribulations. But not only did his family not suffer what the poets call a bone-chilling wind, they had a fire burning in every room, and they feasted on the richest of delicacies until the doctor warned them that they had better add some fruit to their diet. “My wife doesn’t look anything like she did long ago when I met her in a small room in the pleasure quarters. If I weren’t so clever, it wouldn’t be possible for me to experience the happiness I do when she wears Western clothes and looks so beautiful that I can’t believe she’s my wife. I am, quite simply, a winner.”

His wife Oyu paused on the threshold as she was about to enter his study. Usually so restless, he appeared to be deep in thought, although he was actually just busy admiring himself. She wondered what was making him look so pensive. She smiled suddenly and went to his side.

Oyu: “Aren’t you bored staying home all day? What was it I wanted to ask you? . . .That’s it, I heard that Matsushita was fired yesterday.”

“That’s right,” Tamotsu said smugly.

Oyu: “It was probably because he was too cheap to take his bosses out and toady up to them.

Tamotsu: “That can’t be. . .Well, partly.”

Oyu: “You’re the same way, so let’s treat everyone someday soon, shall we?”

Tamotsu: “Not for that reason, but it’s a good idea.”

Oyu: “So I need to have a new outfit made by then.”

Tamotsu: “You’re very clever. Your tricks show how serious women really are about clothes. Just when I thought you had suggested a banquet for my benefit, it turns out that clothes. . . But wait a minute. You had one made the other day, so you don’t need one now, do you?”

Oyu: But everybody’s already seen that one. If I wear the same thing all the time, it will reflect poorly on you.”

Tamotsu: “If I can’t even remember what you’ve worn, how could other people?”

Oyu: “You have a bad memory. We remember what everyone wears, men and women. Shall I recite some for you?”

Tamotsu: “I can’t stand that kind of nonsense. It doesn’t matter whether someone knows what you’ve worn.”

Oyu: “That’s not true.”

Tamotsu: “Women are such an annoyance. . .Apparently you won’t be satisfied unless I say yes.”

Oyu: “There’s nothing annoying about women. It’s just that socializing has become popular, creating these kinds of problems. There’s nothing duller than socializing. Some of the wives who spent a lot of time in school memorizing all kinds of trivia ask me bothersome things. . .On top of that we constantly have to have clothes made that are so tight you can’t eat anything while you’re wearing them. If it weren’t for this, I don’t know how many times a month I could go to the Shintomiza theater with the money I spend on clothes.”

Tamotsu: “Be that as it may—didn’t the Hayashi girl come by five or six days ago? You never tell me when we have female visitors.”

Oyu: “That’s not all. Apparently she is now head of the temptation group.”

Tamotsu: “You mean, temperance group.”

Oyu: “Whatever you call it, the group prohibits both men and women from drinking. That’s not all—you also can’t eat Nara pickles or marinated persimmons. Apparently she—a woman!—even gives speeches telling people they have to quit drinking, because where there is sake there naturally are teahouses, where some people fall madly for geisha.”

Tamotsu: “Is that so? I should have joined the group early on. Then I wouldn’t have been made to fall madly for sake or geisha. Madam?”

Oyu: “There you go, teasing again.”

Just then their student lodger spoke outside the sliding doors. “Four students are at the door. If you’re available, they’d like to see you. They say that you’ll know them when you see them. What should I do?”

Hearing this, Tamotsu scowled. There’s nothing as annoying as students, he thought. They won’t comply if I try to chase them away immediately, but if I see them, they’ll make the usual requests—that I take them in, give them money to travel, or get them jobs as public servants. Settling the debate in his mind, he said, “Show them in to the sitting room.”

|

Illustration by Matsumoto Fūko |

While waiting, the four guests had been exchanging glances and whispering until they were finally ushered into the sitting room, where they lined up on one side. Their faces were tan, but their arm muscles weren’t bulging; their kimonos were of the striped cotton kind common in the country, but not ragged. In other words, they didn’t appear to be the pretentious type of students. Their host eventually arrived, and each student greeted him briefly in turn, looking calm. Tamotsu didn’t recognize a single one of them. After staring at them for some time in suspicious silence, he spoke. “I’ve never met any of you, but your hometown is the same as mine, isn’t it?”

A: “I gave you my card just now. My name is Honda Rokurō. I and these two, Yasuoka Kumazō and Tanaka Ken, are from your hometown. Mononobe Hayama is from Kōchi in Tosa.”

Tamotsu: “Yes, I’m familiar with the names of the three of you. Did you come here for school? . . .When?”

Honda: “It’s been about three years. I’m at Kanda Law School. I’m beginning to understand the law just a little. . .Yasuoka and Tanaka came to Tōkyō recently. Both had wanted to come for a long time, but their fathers gave them a hard time and wouldn’t let them come, so. . .”

The two spoke at the same time. “Our fathers felt that if we came we would surely become lazy. . . They said we should do our studies in the country, even if it is backward. . .And that if we didn’t fall into indolence here, we’d start socializing with people who talked about people’s rights and freedom and such and be thrown in jail, causing them grief. So we weren’t able to come till now.”

Tamotsu: “They have a point. A lot of the students who come here to study are violent; in other words, they’re actually jealous. If everyone in the world could ride in a four-wheeled rickshaw and build a white castle they’d have no complaints. They seem to be ashamed that these are their complaints, so they don’t mention them, they just complain as much as they want to about the conduct of bureaucrats and about politics. It’s actually laughable. . . It doesn’t matter how much they brag or fume, it won’t do any good. . .In terms of knowledge, scholarship, experience, and power, bureaucrats and students are different, so it’s natural for the latter to be losing. You’d think they would understand this reasoning, but somehow. . .I shouldn’t be saying this around you, but students are really a nuisance. . .The safest thing for you to do is to go back home and follow in your fathers’ footsteps.”

Tanaka: “You’re right. . .But even in the country, you can’t be too ignorant.”

Tamotsu: “That’s right. I’m not arguing in favor of ignorance. But I don’t believe you should waste your brain on anything political that won’t benefit you.”

The face of Mononobe, who had been silent thus far, was burning red when Tamotsu finished talking. Mononobe, a stutterer by nature, was an earnest, serious man who appeared to be very uncomfortable with conflict. But when he saw someone doing something wrong, he admonished them directly, regardless of the consequences. It was a pity for this straightforward fellow that the slightest thing could cause him to spout an extreme argument out of keeping with his habitual modesty. If you could dissect him and see into his true nature, you would have to feel sorry for him.

Honda and his two friends quickly realized that Torisu Tamotsu’s face wore an expression that all but told them to hurry up and go home. Uncomfortable, they urged Mononobe to say his farewell, but he was oblivious.

“I know it’s inconvenient for you for us to turn up all the time, and I apologize, but what I want to say is that I believe that public servants who work just for the money and not for the good of the people should resign. The loyal warriors who gave their lives for the Restoration and are now white bones beneath the ground surely deplore the situation. As you know, Sir, those loyal warriors walked miles in straw sandals, barely staving off starvation with only the few rice balls they carried. They walked through the rain and slept in the dew; even when they fell over dead from multiple wounds, the word patriotism was always on their lips. In their hometowns, their white-haired mothers waited day and night for dead sons who would never come home. Newlywed wives, their eyes swollen from crying, spent the cold winter nights alone in bed, dreaming of their soldiers. As for the loyal warriors, being flesh and blood, not stone, they must have felt as if they were being torn apart inside from the morning whistle to the moonlight march. Their pulverized bones and seared spirits brought peace to the entire nation as well as to every particle of dirt in the land and brought every man, woman, and child into the imperial fold. Whose achievement do you think this is?”

The other three addressed him in unison: “Stop it, Mononobe. Let’s say our goodbyes.” Mononobe’s passion seemed to have rendered him deaf to their pleas. He continued.

“Mr. Torisu. Listen. How sad must those countless men be, who accomplished their goals but ended up as white bones in a field, exposed to the elements? The government feels that erecting a monument or building a shrine is sufficient to honor their souls—and these are a partial way to fulfill its obligation to them—but those patriots under the ground cannot possibly be satisfied with such merely superficial trappings. Only if we strive—not to become complacent in a time of peace, not to forget the bitter trials—will they be able to rest in peace. But as long as you ignore the wives who are starving despite a year of abundant harvests and the children who are crying from the cold during a warm winter, while you make your homes in towering castles, travel in jeweled rickshaws wearing brocade robes to protect you from the sun, indulge yourselves endlessly, subject innocent people to hard labor while making bedfellows of cunning wealthy merchants, and engage in corruption, you won’t be able to cover your stench, no matter how skillfully you drape it with silk. If you don’t stop to think about this now, you will regret it keenly. What have you accomplished that has earned you the right to be in the government for so long? How greedy you are! If you want to amuse yourselves, go off to the mountains, the rivers, do whatever you want, but don’t do it while in government office.”

At these words, Tamotsu could not contain his anger. “Shut up!

You are only a student. What do you know? Hurry up and get out of here. If you don’t. . .”

“You’ll have me arrested. Fine, arrest me. But the righteousness of what I say cannot be confined or beaten.” It was as if his rhetoric had reached the boiling point, and even when his three companions did everything they could to try to stop him, he wouldn’t listen. Both sides were hurling insults at the top of their lungs, which brought a panicky Oyu in from the next room. Something had to be done. She sent a servant to summon the police, one of whom had known Oyu in the past and had told her that she should notify him if anything happened. The policeman came running in, and the fierce debate he heard coming from the next room made him very angry. He must have thought that he had to do something, and when he did appear in the room, everyone was so surprised that the arguing stopped. Bowing briefly to Tamotsu, he turned to the four students, looking and sounding stern. “Even if you are speaking as private citizens, I’m taking you in on charges of willfully slandering the nation and insulting a government official,” he proclaimed.

Mononobe asked him to clarify which part of his speech had slandered the government. He was told that a question like that didn’t deserve an answer; he was being taken in regardless.

Chapter 4

Newspapers rarely shrink from exposing the dishonorable ways of men to the world

Because they were renting the house, they could walk on the tatami mats with their shoes on. As for the vaunted pillars without joints, said to be made of cedar or cypress, in these people’s hands they had become pitifully full of nail holes. A certain foreigner plucked the samisen in late-Song-dynasty China and sang, as he ceded power to the next ruler, “Let no one among my descendants be born to the imperial house”; there is indeed a bit of that in play here, as the master sits in the living room saying to himself, “We must never become home owners.” It was a Japanese-style room, but the placement of the table and chairs and the generous arrangements of flowers in the most modern vases somehow gave the impression that this was a house that had a lot of visitors. In the garden next to the entrance, the tired look on the face of the rickshaw man, whose vehicle is painted black with a small gold crest, lets you know that a successful, well-traveled man lives here. If you are wondering who, it is Kinoshita Kurasa, a popular lawyer of our time. Having gotten up at midday, he is having a meal with his wife Otsuta when something suddenly strikes him. “Oh! I forgot to talk to you about something. As you know, we have to give something to Kagami, but we can’t possibly give him money, right?”

“We have to give him something worth how much?”

“Around 50 yen, I guess.”

“That would be difficult. Very. Because some of last month’s bills were left over.”

“Yes, that’s it.”

“That’s what? I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“How can a teacher who graduated from normal school not understand this? The world is basically like Kagami’s name, that is, a mirror. You took him to be a splendid person because he was wearing a splendid outfit, didn’t you? If you still don’t understand, think about the adage about one’s place in the afterworld depending on one’s wealth.”

“In that case, as far as that goes, there’s no way you can win.”

“That’s why it needs to be merchandise.”

“If so, I’ve got something good. Mrs. Kagami is dying to wear Western-style clothes. And because she has no experience with them, she doesn’t know what they cost. If she is given some clothes made by Shirokiya for 35 or 40 yen, she’ll think they’re very expensive. Although if that wins the lawsuit for us, it will be a pity for the other side.”

“That’s the way it is. There’s nothing strange about one side winning and the other losing. Our good fortune is their bad. No matter how much we may be right, right doesn’t necessarily win, and that’s how the world turns. Speaking of which, the newspaper’s late today. Is it here? If it is, give it to me right now. The People’s Rights News, is it? What do they mean by ‘Patriots’ Misfortune’? Oh, it’s about Torisu.”

“It can’t be about Torisu. He’s no patriot.”

“It has something to do with patriots. Let me read it.”

Patriots’ Misfortune

Yesterday around 10 AM, four men whom the radical extremist party always associates with staunch conservatism, Mononobe Hayama, Honda Rokurō, Yasuoka Kumazō, and Tanaka Ken, visited the home of Torisu Tamotsu on unknown business, and the subject of the current political situation happened to arise in the course of a wide-ranging discussion. Although it is true that Mr. Mononobe, the most moderate and straightforward of the group—and one who is not, by nature, an eloquent orator—reached a patriotic fervor that led him to speak a bit roughly, it is highly suspicious that Mr. Torisu, who had previously alerted the police that such an occurrence might arise, sent to them for help. The officer arrived and said that they were insulting a government official (despite the fact that Mr. Torisu had agreed to meet with them privately). The officer adamantly refused to listen to their side of the story, saying that he was not obligated to do so at the scene, and he took them into custody immediately. At the police station, their names, addresses, and ages were recorded before they were placed in detention. The men said that their innocence would be recognized as soon as someone familiar with their everyday activities was consulted, adding that their having been taken into police custody was highly questionable. It is their misfortune that they have to be locked up for even a day or two, given that they will no doubt be declared completely innocent in open court. Ah! The iron chains of jail. You don’t realize that someday the patriots you are persecuting today will sit in judgment on you! You and your ridiculous iron chains! Your iron chains! Unfortunately, we were not able to learn the nature of the criticism that was directed at Mr. Torisu by the aforementioned men. We will report it as soon as we find out.

“This will be censored,” Kurasa said with a bitter smile as he finished reading.

“They can stop someone from writing something that actually happened?”

“You think it matters whether it happened or not?”

“Those poor patriots. They won’t even have a heater on a cold day like today, will they?”

“You certainly ask the easy questions. They’re in hell—a heater is the least of it.”

“You know that?”

“Everyone hears things.”

“Some of them probably have wives. How sad their wives must be. Mr. Torisu sounds hateful, doesn’t he?”

“That’s because we’ve only read about it in this newspaper. If we read another paper, on the other side, we’d say the students are hateful. You never know, because everyone is out for their own cause. But I’m going to go see Torisu,” Kurasa said, and he took off in his rickshaw with a light heart.

Although it was not Saturday, Torisu Tamotsu, who liked his monthly pay but hated working, was ensconced in an inner room of his home. He was thinking about nothing in particular, completely forgetting how short life was, when his wife Oyu, who was tapping her tobacco pipe in the adjacent room, spoke through the sliding doors onto which she was leaning. “You have company.”

“If it’s students, tell them I’m not here.”

“It isn’t students. Please, come on in.”

He realized that the visitor had already come in as far as Oyu’s room. Tamotsu and Kurasa, boon drinking companions who had shared many secrets, seemed almost closer than relatives. “Oh, Kinoshita. You’ve seen the paper?”

“What happened to you yesterday must have been awful. Students are a nuisance for all of us. But what goes around comes around. Today’s teachers made trouble for their teachers as students, so . . . when these students become teachers, they will have to look after the same kind of troublesome students they used to be. But they are a disagreeable bunch. If you push back at one, he gets mad. So what happened with those fellows yesterday?”

“It says they were put in jail.”

“I think that just might make it harder to clean up the mess. But when it’s gotten to this point, the only thing to do is to fight back hard. If they suffer in detention for a while, they’ll probably be more careful next time. It won’t become that much of a problem publicly, because insulting a government official is at the heart of the matter. Their party is the most persistent and has a large membership, and they say that its members don’t engage in any kind of dissipation the way the other students do. Their manifesto says No stealing, no killing, no swindling, no bars. Apparently it also has provisions about their obligations to help their elders and nurture the younger generation. From what someone on the other side told me the other day, Mononobe and company are definitely a strange breed, but as far as their propriety is concerned, no one can come close. They say that organizing hinders their movement, so they don’t establish a formal group, but judging from the way they conspire with one another, they seem to have unbreachable friendships.”

“Do they really have a lot of party members?”

“They’re said to be quite popular. It isn’t just students; there are some financiers, too. And scholars, I hear. Their popularity is really a blot on the nation.” Before he had even finished speaking, Kurasa pulled out his gold-plated pocket watch and said, “Oh, no. We’ll discuss this another time.”

“You’re leaving already? Let’s talk about something. . .”

“I know. I’ll definitely come back soon.”

“You’re as hasty as ever.”

“Yes. . . I mean, no, I have to go.”

Chapter 5

The one who has struck it rich sings of peace, while the tears of the patriarch moisten the rice field put up for public auction

Torisu Tamotsu hadn’t been home when Takazono Kan’ichi had called upon him previously, and so Tamotsu decided to repay the call today. When they reached the Takazono house, he had the rickshaw man ask whether he was at home. The very sweet voice that replied to his brusque inquiry was not that of a servant but that of the lady of the house. A bit embarrassed, Tamotsu asked, “Is your husband at home?”

“Yes, he is. Please come in.” She led him into the sitting room. There were two or three servants around, but there wasn’t any need for them if the wife was going to receive him and show him in. Her gestures as she did so were elegant, not like those of a maid, and she acted as though she had been charged with looking after him. The way she tried surreptitiously to help him avoid feeling awkward and put him at ease was nothing like that of an ordinary, uneducated woman. That kind of woman would merely await her husband’s orders and then say in response, here is the ashtray, here is the brazier, here is the tea, and here are the sweets, after which she would sit stiffly in one corner of the room like a decoration whose manner all but said to the guest, hurry up and go home.

If you are wondering what Takazono Yoshiko looks like, she seems to be about twenty-three or twenty-four. Her hair, which has been pulled back gently, doesn’t smell of oil. The way the breeze tries to tease six or seven strands of hair out of her bun evokes the first green buds that appear after a spring rain in the mountains has washed away the red dust. Her crescent-shaped eyebrows remain in their natural state; her nose is neither high nor low. Her coloring is like that of a white peach blossom, but a blush of scarlet crabapple shines through her cheeks. Her lips are firmly closed, but when she speaks, her bright, clear words sound serene, like the flow of a mountain stream in the distance. Her movements are light yet precise, proud but not arrogant, and they emit the pure fragrance of a heavenly orchid while lending her an aura of nobility and charm. Most women this beautiful learn early that there is no one in the world who compares with them. They can do nothing all day but open and close their compacts over and over thinking, “Sadanji, who played Kosan of the teahouse at the Shintomiza the other day, wore his glossy hair in a bun held in place with a very stylish ornament. . . .But then again, Yanagibashi’s Tsunehachi was incomparable, coming out of the bath with his hair swept up loosely with a comb and wearing a finely striped kimono of Nishijin weave complemented by two obis, one of black satin and the other, twill. You can’t do that with makeup on. I’ll have to take off the powder I put on this morning. . .I wonder why I am so pretty. If I want to look sophisticated, I can do that, and if I want to look stylish, I can do that. It’s a waste to keep a face this pretty at home.” Women like this spend the prime of their lives vainly parading their faces around town like priceless showpieces or else shut themselves up at home doing their makeup while conversing with their mute mirrors. Not Yoshiko. She seemed not to realize who people were referring to when they spoke of “a beautiful woman,” and she always wore exactly the amount of powder appropriate for a modest woman. She didn’t know that not wearing anything that called attention to itself was a way to keep people from tiring of her appearance. Pity those who lose their natural beauty by obsessing about their appearance and in the process create an artificial ugliness.

Tamotsu looked at Kan’ichi and said, “Did you hear what happened the other day, Professor?”

“Did something unusual happen?”

“Yes, something involving me.”

“I haven’t heard a thing.”

As he angrily related the violent rhetoric of Mononobe and his associates, Tamotsu was aware that the views of the head of this household were in conflict with those of some people currently in the administration. Previously Kan’ichi had occupied a high-level post, but because he didn’t share the government’s beliefs, he felt that remaining in office would be tantamount to being greedy and dishonorable. Since leaving his post, he had changed into someone who dressed and ate simply, lived in a shabby house in the country, and didn’t seek the company of others. He made it his business to keep his gate firmly closed and to climb only his own moss-covered steps. He cultivated vegetables from time to time and didn’t feel that his household wanted for anything. He had his beloved wife to talk to and piles of books to read. He had no reason to be resentful, having the strong love of his wife Yoshiko, who had enough education to be able to be a comfort to him and enough knowledge to be able to help him in his work. Men and women of the world, how few husbands and wives have a happy life like this, loving and helping one another! Even if there are couples who speak of happy times, it is usually when they are reminiscing wistfully about their courtship. That should suffice to show that few have tasted true happiness.

Although Kan’ichi had taken refuge on land from the sea of bureaucrats because he disagreed with them, neither his actions nor his words bore any tinges of the tides of dissatisfaction, and so it should have been obvious that he bore no ill will, unlike those who become angry as soon as they leave their posts. Tamotsu’s distorted worldview led him to believe that ignorant young patriots went around engaging in violent activities because a dissatisfied Kan’ichi had incited them and directed them to take various measures. With this in mind, Tamotsu pushed aside any thought of their normal friendly interactions and said, officiously, “We know the lengths to which these ignorant, powerless youths will go. Nevertheless, I think that there is definitely an instigator.”

Kan’ichi remained silent. Tamotsu turned to Yoshiko. “Don’t you agree, Ma’am?”

“It’s not that they are incited, exactly, is it? The students don’t lie or sugarcoat; they are sincerely angry with you people, aren’t they?”

“Why would that be?”

“There’s no particularly deep reason behind it. A lot of the students are poor, and it probably isn’t very pleasant for them in the winter when, frozen to the skin in a threadbare fifteen-mon jacket, they stick their necks out the windows of the second floor of the boardinghouse where they live three to a cramped room, only to see a government official bundled up in an otterskin overcoat pass by sedately in a two-horse rickshaw, his driver able to clear the road of traffic with a simple command. They probably go on from there to think all kinds of things.” Just as she was saying this, the maid brought in five or six calling cards. Appearing to find this annoying, Tamotsu took his leave, arranging to come back another time.

Kan’ichi knew the six guests who came in then, but Yoshiko did not. Two wore Western-style clothes; the rest, Japanese-style.

Yoshiko was seated. Though she had guided them to their places and performed all the general courtesies flawlessly, the seated guests behaved as though there was no one in the room but Kan’ichi. Not one of them even bowed to her. Some of them looked at her while pretending not to, thinking, so this is Kan’ichi’s wife. Her presence there was awkward, but Yoshiko wanted to know what they had come to discuss, and so she sat there, listening and making no move to leave. Each one of the guests looked truly angry. Some maintained a purely dissatisfied expression, while others appeared to affect one out of fear that if they didn’t look dissatisfied they would not be recognized as the clever patriots they were. The aggrieved group stared at Kan’ichi in silence for a while. Finally, one of them took out an extremely grimy grey handkerchief and, continuously wiping the sweat off his palms, spoke in a scratchy, uncertain voice.

“Professor, what are your thoughts these days? We’ll be in trouble unless someone a bit extraordinary steps forward, but there doesn’t seem to be anyone like that, does there?

“Six or seven years ago the countryside was overflowing with righteously indignant patriots, but the fire seems to have gone out now. Some were probably cajoled by the government’s clever methods, while others were probably intimidated by their strong-arming. The way it looks today, the moment is gradually going to pass us by. How can we stop it? Don’t you find this to be most deplorable, Professor?” He spoke fervently.

Unruffled, Kan’ichi replied quietly. “Yes, it is completely understandable that you all would deplore the current state of affairs. Especially if you’ve witnessed the misery in the countryside in recent years and then seen the luxurious ostentation in the capital, I can imagine that you have feelings that even the patriots there don’t have. But as long as there are all different kinds of people in the world, young and old, wise and dull, you can’t expect everything in society to be in balance, and one can’t automatically censure those who pursue the height of extravagance in everything they do. As far as the masses in the country are concerned, they think of their straw huts, which can barely keep out the rain, as golden pavilions and tall towers. Diligently gathering eulalia by day and weaving it into ropes by night, the women are so engrossed in their looms that they forget the winter cold, and the children believe potato gruel to be the best-tasting food there is. Never in the course of a lifetime will they wear silk, taste fine meat, or sleep on silk bedding. They get up early and go to sleep late, but even though they sweat blood over their farm work, they are still unable to avoid the demands of the tax collector. The land they inherited, which connects them to previous and future generations, is sold at public auction while they cry, heartbroken, and a lot of it also seems to end up back in the hands of the government. At a time like this, many city gentlemen indiscriminately don the trappings of enlightenment and peace, ignoring the fact that they are emptying the national treasury in the process. Those who are out for themselves are rewarded for currying favor and preaching peace, some of them suddenly becoming hugely wealthy, while not a few others unwittingly do the government’s work by expressing their love for their country and ending up in jail. This probably contributes to your anger as well. I sincerely respect what you are trying to do, but there is something else I want to say to you. Our nation places its hopes for the future in its youth; that is, in you. It would really be regrettable if our promising youth believed that their life’s work was to run around the country vainly spouting vague, restless rage. That is something that can be done in place of chatting over tea by carefree retirees who are already old and coddling their bodies and minds. But vigorous patriots should give maximum effort to their every endeavor, whether it is education or enterprise, cultivating their strengths until the public acclaims them as qualified to stand on their own two feet and they have gathered sufficient experience. Only when they are truly able to debate what is right and wrong for the future will they benefit both themselves and their country. No matter how compelling their arguments and how upright their spirits, youths lacking in both education and experience will never be able to move the public as long as they have just one argument and one spirit. You can’t be like a drunk who sings the same tune over and over in an attempt to raise his spirits. In other words, I think that it will be to your advantage someday if, rather than running around propounding empty theories, you become practical and gradually nurture a promising political climate. I have spoken to you from the depths of my heart, but I will understand if you respond with words of angry disrespect.”

The six guests who heard Kan’ichi’s warm speech did not all feel the same way. The most radical among them, who would have a tendency to say that Kan’ichi should hoist a flag right then and there and assemble an army of righteous patriots, were surprisingly moderate: their initial displeasure had turned to absolute admiration and the realization that this is what they had expected from someone with a reputation like his. It was very fortunate, because if they hadn’t heard his speech today, they would have joined those who run around preaching empty words that benefit no one and perhaps even have destroyed themselves along the way. Others felt that what they had heard today was a great warning that they needed to share with their fellow activists. Everyone expressed their gratitude for what they had received, and they said their goodbyes wearing such mild facial expressions that they seemed to be entirely different people from the rude students who had come in earlier.

Chapter 6

A woman’s love thoroughly warms the frozen mist along life’s pathways

Withered banana leaves may never find their way into poetry. But the wild chrysanthemums blooming seductively in the gentle breeze and the crimson maple leaves transforming the Ueno and Asuka hills into brocade led great numbers of men and women from all rungs of the class ladder out to promenade in earnest on this mild mid-autumn day. Not Takazono Yoshiko, however. Having finished preparing her husband’s winter wardrobe, she was walking alone in her garden, thinking of composing a poem about the charming chrysanthemums that had bloomed along its bamboo fence. “Ah. A noble clothed in white silk might appreciate the sight of chrysanthemums against a background of purple and crimson curtains, but they appear most beautiful here, outside a humble dwelling. Here they proudly announce the season in a rustic garden buried in fallen leaves amid softly floating clouds and wild birds.” Such were her thoughts when Kinoshita Kurasa’s wife Otsuta arrived. Yoshiko met her at the door herself and ushered her into her study.

Otsuta, a normal school graduate, had had a reputation as a sharp and lively woman since her school days, when she had been a source of anxiety for her elders. If she continued to mature along these lines, what kind of woman would she turn out to be? She may be somewhat literate, they thought, but her manner isn’t warm and pliant; she may understand English, but she writes a poor woman’s hand; she may be a skilled knitter, but she cannot mend a torn sleeve. This had worried the men in her family tremendously because they knew they had to marry her off. As for Otsuta, not only had she lamented the fact that those men had no understanding of the times they were living in, but occasionally she had confided to her friends that because of their ignorance it would be a big mistake for her to let these relatives take charge of her life. The gossips said that a friend had introduced her to Kurasa and that her family had been against the marriage at first but eventually had had to come around because Otsuta wouldn’t listen to them.

“Your husband isn’t home today, Yoshiko?”

“That’s right. I’m lonely, so I’m happy you came.”

“I really envy you.”

“Why?”

“You two get along so well. I have a problem, Yoshiko. My husband was really agreeable at first, but lately he complains about every little thing, and there’s nothing I can do about it. I intend to do what I absolutely must to fulfill my obligations as a wife, but it does me no good to go along with every single thing he says. I thought it might help restore his mood if I got a little irritated, but it didn’t. Now it seems strange to me that I thought he was such a good person at the beginning. We don’t have any children yet, so I’d rather. . .”

“Don’t talk like that, Otsuta. Why aren’t you able to get along the way you did at first anymore? A husband and wife are one unit, so you and Kurasa are parts of the same thing, and there is no reason that you should find waiting on him to be difficult. There have always been a multitude of doctrines about a woman’s obligations to her husband and her manners and such, but a husband will never take comfort in obligations or manners that are performed without sincerity. The best way for you to feel satisfied with one another is to envision a capacious basket labeled “love” and include everything in it. You went to school for a long time and learned a lot of things there, so I’m not just flattering you when I say that anyone who has taken someone as clever as you as his spouse is extremely lucky. So there can’t be anything troubling you. If you would just expand the love you have in your heart for Kurasa, you will find that it will cover over all of his complaints.”

“Listen to this. There are no differences between men and women. In which case, a woman cannot just tacitly agree with a man’s every whim and complaint, can she?”

“I don’t know whether or not there are really no differences between men and women, but I don’t think a woman has to sit by silently.”

“What’s different between men and women?”

“Everything from their body composition and psychology to the fact that in Japan today most men have a certain amount of wealth, while most women have absolutely nothing. The same goes for their occupations.”

“So you’re saying that because women have no wealth and no occupation they have no choice but to surrender to men?”

“They never have to surrender.”

“Why not?”

“Because women have something more valuable than wealth or an occupation.”

“Really? What do women have?”

“It is something that men want, and if they get it they do not complain, even if they lack wealth or work. It is nothing other than this: the gentle, warm love that is peculiar to women. Love is highly effective and influential. Men get chilled to the skin out in the cold, cruel world, but they are able to warm themselves in the waves of love. They are able to wage a fight for what is right—never wavering, even when their lives are at stake—because of the consolation of women’s love.”

“That may be, but you can’t love when you are being trampled on. Talk like that gets on my nerves.”

“Is that so? All right, I had better stop, because it isn’t right to upset a guest. I got carried away talking and forgot to mention that I heard you moved the other day.”

“Yes, our former place was too far from the courthouse. . .Moving is really onerous. It just wasn’t enough for our students to petition City Hall the customary one hundred times; it took a full thousand until our request was finally granted.”

“You must be exaggerating.”

“If you don’t believe it, try moving yourself. At first I didn’t know how City Hall works, so I just kept wondering what we would do with all of our baggage. There are no restrictions as long as you pay the shipping fees. City Hall is strange, though—on the one hand they say that these are the rules, but on the other they say something different. Then they say you have to appear on such-and-such a day at such-and-such a time in the morning, and when you show up at that time they make you wait, saying that the relevant person isn’t there yet, and then they say that’s all for today, come back tomorrow. And isn’t this strange? That Mrs. Torisu is always changing her mind and she moves often, so I thought she would be sympathetic to exactly this problem, but when I mentioned it to her the other day, she spoke a bit haughtily. She said that that may be the case for us, but that they have people at City Hall for whom they have done favors, so all they have to do is send a student there and the matter is settled. When you’re in the city, all of your affairs have to be conducted directly at City Hall, but I wish that they would accept the paperwork even if a word or two is spelled wrong, as long as it makes sense. Although you’ll probably say that our love as public citizens just isn’t enough.”

“That’s a rather harsh attack, isn’t it?”

“Perhaps. In any case, everyone has been talking about the fuss Torisu’s students made, but apparently the root cause was something minor. But those students have plenty of enemies as well as friends, so everyone was talking about it, and not only were the newspapers suspended for publishing articles with ominous headlines like “Patriots’ Misfortune” and “The Selfishness of Bureaucrats,” but suddenly three or four students who live in boardinghouses in Kanda were arrested as well, it seems. My husband says that the newspaper was in cahoots with Mononobe and company. In any case, when they appear in court, Kurasa will probably be dragged into the case, but he says that nothing pays as little as lawyering, so he always makes a sour face about it.”

“But it’s an honor, so it’s a good thing, isn’t it? There is so much mistrust in the world that it’s hard to be found not guilty even if the charges are unfounded, isn’t it?”

They spent time conversing like this. In the past, when two women met, they would only exchange comments about the weather, or their opinions about clothes, or the talents of actors, or how kind or unkind their in-laws were, or how obedient or disobedient their servants were, but listening to Yoshiko and Otsuta’s conversation, you can get an idea of how things have changed for women. They don’t merely imitate men’s noisy political discussions indiscriminately; they also play songs on the koto praising the light of the moon in the autumn wind, or take to the garden with their walking sticks in the spring to study the grasses and trees. Their hearts are filled with the stuff of art. Inhaling the fragrant scent produced by their flowing words, you have to acknowledge the great refinement that women bring to society.

Chapter 7

The woman with red sleeves plying her needle in the light of the spring lantern lends strength to the bearded writer who sits beside her, wielding his brush

From the time she was very young, Takazono Kan’ichi’s wife, Yoshiko, was very different from ordinary girls in terms of her activities and interests. She liked to read and play the koto, and it seemed that what suited her most was to fantasize about placing her big dreams on a small boat and sailing off with them across a vast expanse of water, or about donning rough straw sandals to ascend into the clouds and from there climb the highest peaks. At other times she would sit sewing by a lamp in the spring, with students and beautiful women, or overwhelm men with her literary talents. And this is why mountain recluses considered Yoshiko a friend of the mist; those who composed Chinese poems considered her a friend of the poet and the calligrapher; and women who sewed and made music considered her a graceful friend of those whose domain was the inner rooms. In this way, Yoshiko did not socialize in just one arena, and as her knowledge expanded naturally, she drew her own conclusions about each and every thing. Her gently graceful manner lacked the slightest trace of arrogance. By the time she was twenty-nine, Yoshiko was so famous that those who had never rubbed elbows with her felt undeserving. But secretly, in her heart, this troubled Yoshiko; she felt that to achieve fame so early in this fickle world could be a source of trouble. In fact, when she really thought about it, she didn’t know why she was famous or even how to find out. Receiving praise for no reason is a precursor to being criticized for no reason. It was truly unbearable, and so she feigned illness and cut her social ties. Her reputation immediately went into a decline, and false rumors about her arose, but this did not bother her in the least; in fact, she acted as though this was as it should be. She avoided gossip wholeheartedly, shutting herself up in her study and looking at books from countries around the world. Yoshiko was especially concerned about the lack of education for women in our country. She believed that as long as education for women was lacking and women were not valued, society would not advance. Thoughts like these were her main preoccupation, but she was by nature able to endure pain and feel empathy, and not act boastful toward the weak or ingratiating toward the strong. Many people avoided Yoshiko, thinking her arrogant because she confronted people directly when they were disrespectful toward her. In the past Yoshiko had told a close friend, “When people are disrespectful to me, I don’t get angry at them to show off, I just can’t bear how it makes me feel.” She may also have said something along the lines of, “If I am disrespectful to someone else, I will not shrink from the consequences, whatever they may be.” Praise and blame tend to be delivered too lightly. It is very rare for a woman to be able to read and discuss current events, so this earns momentary praise, but in a country where men are respected and women reviled, this type of approbation is truly superficial, even insulting, rather than sophisticated or appropriate. Because of this, since ancient times most talented women have taken positions considered appropriate for them, few of which allow them to use their skills. In early spring when the flowers are staging beauty contests, such women act almost like nuns who have abandoned the world, forcing themselves to bury their makeup in the ground, shorten their sleeves, and narrow their sashes. In extreme cases, they live in a valley far from civilization, crying at the rain, grieving over the moon, and pondering the sadness of the shadows of geese flying overhead or the cries of the deer. Always alone at the window composing poems and songs, they envy the flight of the butterfly and resent the falling of the blossoms.

In one respect, you might say these people are foolish because they are so narrow-minded as to experience a world full of pleasures and amusements as a place of acute pain. But insofar as the standard is that men are to be respected and women reviled, no matter what skills women may have, unless they abandon them and feign ignorance, they won’t be able to become wives and keep house. If, on the other hand, they were allowed to use their talents to help their husbands and raise their children, their husbands and children would be unspeakably happy. At a time when such evil customs hold sway, those who tend to stand out must force themselves to act like wooden dolls once they get married, while those who can’t bear to abandon their skills have to live lonely, solitary lives.

Yoshiko pitied the women of former times whose lives ended in pain because they were not able to use their talents to please themselves or others, and she hoped that from now on women would be able to get out of that rut and use them to bring happiness to themselves and benefit others.

Yoshiko’s husband, Takazono Kan’ichi, was not affected by the vicissitudes of her reputation, because he had always felt sure of her, and now he became even more steadfast in his love for her. For her part, Yoshiko had come to believe that Kan’ichi was the only person who really knew her. Thus when they sat, it was together at the same desk, and when they traveled, it was in the same rickshaw. They studied history together, debating the successes and failures of ancient and modern times, and they shared their innermost feelings, lamenting the present day. There were only three bamboo poles and a few banana leaves in the garden of their poor country home, but they wrote poetry there and did not envy those with a sturdier house and a splendid tower. They rejoiced in their one bookshelf, two kotos, and the southerly breezes that blew as if they constituted the height of elegance, and people envied them keenly, believing that a life like theirs must be what is meant by heaven. They tried to maintain this harmonious existence, but of course it was not enough if only one of them was happy.