|

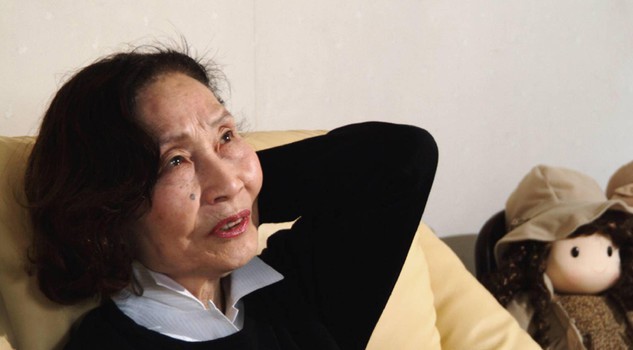

Hayashi Kyoko. Photo by Kanai Mikio, Ansa Lifestyle, August 5, 2015. |

This story was first published in the February 1976 issue of the literary magazine Gunzō and later anthologized in the Collected Works of Hayashi Kyōko (Hayashi Kyōko zenshū) (Tokyo: Nihon tosho sentā, 2005). The original title, Nanja monja no men, draws on the Kantō area dialectal expression “nanja monja,” a contracted form of “najō iu mono ja” (What sort of thing is this?), referring to a large, legendary tree.

|

Urakami Cathedral, Nagasaki, damaged by the atomic bomb. |

By the little stream is a trapezoid-shaped stone. Sitting down on it, Takako looks around. There are no trees. No houses. No people on the streets at midday.

Fires burn along the rubble-strewn horizon. When will they be extinguished?

The sun is too hot. Takako wishes for the shade of a tree. She wishes to see life, alive and moving; even a small ant will do.

Takako died. In October 1974, when she was forty-five years old. The cause of death was cancer of the liver, or of the pancreas, according to some, from a-bomb after effects. Some said that the autopsy revealed the pancreas to be rotten, resembling a broad bean.

Takako was consecrated this year at the a-bomb ceremony in the memorial tower of Peace Park. Her name is bound into a single-volume death register along with those of over 1,000 others who died of illnesses caused by a-bomb radiation in the past year.

Our classmates who died in the atomic explosion thirty years ago are also consecrated in the park. Those girls, still fifteen or sixteen, must have frolicked around inside the dark monument as they welcomed Takako at this thirty-year reunion, saying, “We’ve been waiting for you!” I can see her troubled expression as she tilts her head not knowing what to do, surrounded by those innocent girls. She had become the age of their mothers.

Takako and I went to different girls’ schools. Hers was a missionary school, located halfway up the hill looking over Nagasaki Harbor. My alma mater was near Suwa Shrine. This locates her school in the southern part of Nagasaki, mine on the western outskirts of the city. Takako was also one grade ahead of me.

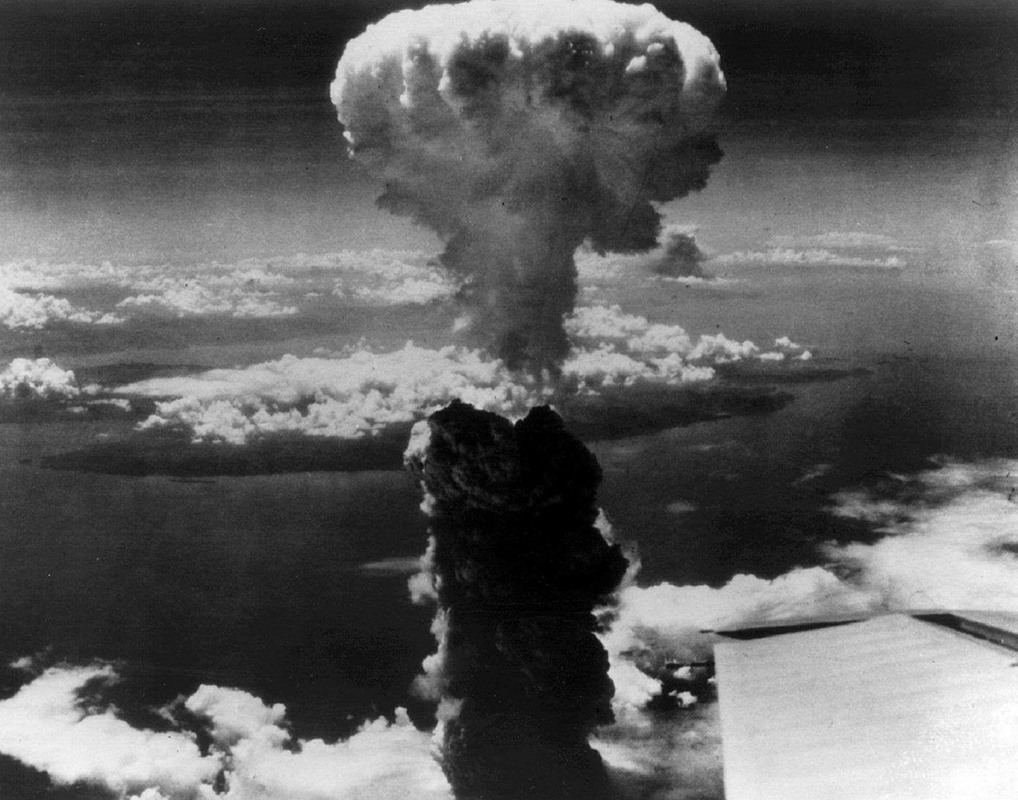

We came to know each other at an arms factory just beyond Urakami, where students were mobilized to work. Both of us were bombed there, but strangely, sustained no external wounds. The factory was not even one kilometer away from the Peace Park where Takako is now consecrated, just four or five hundred meters from the epicenter. Nearly everyone in town met instant death.

On August 9, the day of the atomic bombing, both Takako and I ran desperately from that area. I worry that she may not be able to attain Buddhahood if brought back to the place from which she managed, at great pains, to flee; but perhaps she is simply resting in peace, not thinking of anything now.

I met Takako last about ten years ago. It was early October, just before the autumn festival of Suwa Shrine. The sound of festival drums could be heard from the woods surrounding the shrine. The festival ranks among Japan’s three biggest and the entire city was excitedly making preparations.

When I returned to the city for the combined purpose of seeing the festival and visiting my mother, I chanced to meet Takako.

Walking as far as Kajiyamachi through the arcaded streets of Hamamachi, the bustling quarters of Nagasaki, one comes to a quiet shopping street with less traffic. On that street is a “gift shop” carrying unusual dolls sold nowhere else. I found them by chance when I happened to drop in fifteen or sixteen years ago. The artist, I heard, was a physically handicapped young man who suffered polio when small.

Because they were the work of a single person, the number of dolls was limited. Twenty at most were placed casually on a shelf in the furthest corner of the shop. In the gloom where neither outdoor light nor store lighting reached the shelf, each doll stood in a queer posture. They were made of red clay, baked unglazed so as to make the most of the clay color.

Measuring five or six centimeters in length, each had a different expression and design. What they had in common was that the neck of every doll was forcefully twisted heavenward. And they were wailing, each with a different expression.

When I took some in my hand, I noticed the artist’s fingerprints on the stick-like torso, which measured about five millimeters in diameter. One doll had a flowing fingerprint from its forehead to the pointed nose of its inverted triangular face, which was upturned to heaven, creating a warped expression as if it were about to break into tears.

Like a snail, two eyes of another doll protruded from its head, with two additional red eyes placed just below. The torso of another doll stretched from the legs to the neck, then, at the tip, a face opened up like a plate. On the plate were two eyeballs, lips, and two ears, taken from the face and arranged like fruit.

The one that most resembled the human shape was a minister dressed in black paint. Hands raised like those of an orchestra conductor, face turned up to the sky, he peered heavenward, wailing. All that was there for eyes were two X’s inscribed with a bamboo carver, but they made him look as if he were crying.

Inside the “gift shop” where showy local toys were displayed, the shelf holding clay dolls looked like a dark hollow, alone by itself. As I stood gazing at them, the dolls almost seemed to crowd together and press toward me, making me avert my eyes.

They seemed to have been created from the shadows within the heart of the physically disabled artist.

Although they were eerie, each time I returned to my hometown I bought a different one.

On that day, too, twenty or so clay dolls were arranged on the shelf. Among them was one whose style struck me as novel. Its mouth, torn from ear to ear, opened across its face. White spots covered its body, and the inside of its wide-open lips was colored with vermillion red paint.

Picking it up and placing it on a palm, I looked at it.

“A scream, yes?”

I heard a woman’s voice behind me. When I turned around surprised, my eyes met those of a longhaired woman. Taller than I, her lean body was dressed in a navy blue sweater and jeans. Perhaps because both top and bottom were in cold colors, she looked all the more slender, her facial complexion unhealthy and subdued.

This was how I reencountered Takako. She had long been slender, but seemed one size thinner. I asked her, “Why does he scream, I wonder?”

“He’s in pain,” she answered confidently in Nagasaki dialect.

“What from?” I asked again.

“Remaining this way. It’s painful to be forever exposed to the world.”

Takako picked up a doll with red stripes. It looked like a prisoner, but also like a priest.

“Are you buying that?”

Nodding, I bought the screaming doll. She bought the one with red stripes. We left the store, each with a doll wrapped in a small fancy rice paper bag.

“I saw K yesterday,” I mentioned our common friend who had visited me at my mother’s place. Takako responded with an ironic smile on her lips: “You heard some unsavory rumor about me, I suppose? Fine to spread it as you like.”

Then, looking me in the eyes, she said, “Would you keep company with me, too, for a half day?”

A few houses down, there was a shop that sold freshly baked French bread with two red pay phones side by side at the front. I called my mother, asking her to eat lunch by herself because I would be late.

I bought a fresh baguette for my mother.

“It’s warm,” I said, pressing the bag against Takako’s cheek.

“A woman buying warm bread looks nice and happy, for the moment at least,” she smiled and asked, “Have you been well all this while?”

Apart from a series of a-bomb symptoms that followed my exposure to radiation, I had had no serious illness that would keep me in bed. But I experienced dizziness every day.

“Not necessarily all well,” I answered.

“We’re both flawed merchandise. We must always handle ourselves carefully,” she said thoughtfully and added that, when she felt well enough, she worked as a volunteer at a mentally and physically disabled children’s facility in the suburbs of Nagasaki, work she intended to continue as long as she lived.

As if the autumn sun were dazzling to behold, she blinked incessantly. Taking a good look at her eyes in the bright outdoor light, I saw a bloody bubble in her left eye. It was round, the size of a drop from an eyedropper. The center of the bubble rose slightly and alongside the black pupil produced an odd semblance of two pupils in one eyeball.

“Weird, isn’t it?” Takako pointed at her eye.

“A-bomb illness?”

“Maybe, maybe not. It looks like spot bleeding. It looks like the pupil will absorb it if I leave it alone. My illness, whatever it is, always looks like a matter of ‘looks like.’”

Viewed through her red eyeball, she told me, the faces of healthy, beautiful women appeared to be those of red demons. The prim looks of those women who assumed they were beautiful were so absurd, she added laughing merrily. They may have really looked red, but it was Takako herself who so perceived them that appeared weirder to me.

“That can’t be true,” I said, looking her in the eyes. “It’s true, it is,” she laughed aloud.

The coffee shop was at the far corner of a narrow alley in Kajiyamachi, a small shop with a wooden door that needed to be opened by hand.

It was dim inside. One bartender stood behind the counter. Takako lifted her right hand casually to him. The young man behind the counter said “Hey,” in return.

Takako seemed to be a regular. She also seemed to have a fixed seat, and the bartender placed a glass of cold water and a whiskey bottle on a table near the wall.

She sat with her back against the ecru wall, I on a chair facing her.

The bartender turned on the lighting that hung on the wall. In the illumination, the left half of Takako’s face was brought into relief, and somehow I felt that the bubble of blood was glistening at me. Before thinking, I looked down.

She might have been telling the truth when she said people looked like red demons. The bubble of blood might possess vision, adding color to objects that did not please her. She might not be merely applying that vision to distinguish between beauty and ugliness, but was perhaps observing me and other things in the world with three pupils.

As I took a fresh look at her with this thought, sure enough I felt that her gaze perceived something.

“Any children?” Takako asked, pouring whisky in her glass. I raised one finger.

“A boy,” I added.

“Are his limbs and brain all functioning?” Takako asked unceremoniously. I made no reply.

“Sorry,” she apologized, quickly reading into my feelings.

“I meant no harm,” she added as she lowered her head, “I’ve experienced so many things that I’ve lost all sense of shame.”

Nobody knows where that story began, or whether or not its source was that of a single person. But the story, which spread right after the explosion in a twinkling, went from mouth to mouth with speed and accuracy to be marveled at even when looked back on today. And it was of a reliable nature.

On the twelfth, three days after the bombing, a girl attendant at city hall came by, collecting old newspapers to be used as medicine for treating the burns of hibakusha. Newspapers, she explained, were burned to ashes, mixed with sesame oil, then applied to the burnt skin. “I heard that everyone exposed to that light will die. No matter what medicines are taken, nobody will be cured. It’s scary,” said the girl, twelve or thirteen of age, to my mother from the shade of a tree in our yard. She was even frightened of the sun’s rays.

Just as she said, those who bathed in the flash of the a-bomb explosion died one after another. Those who fled without wounds began to die, blood oozing from their eyes and mouths. Within ten days after the bombing, most of those people were dead.

Takako and I were among those who managed to survive, but the a-bomb demonstrated its real, relentless power over our group. Having projected a fatal amount of radiation at that instant on August 9, it now waited for the deaths of those of us who had survived.

The general outline of the symptoms was nearly the same from person to person.

Green diarrhea and vomiting, a sense of lethargy all over the body, then eventually purple spots. Some lost hair, others spit blood, and in the end they died in derangement caused by high fever. In the intervals of this outline, other symptoms appeared, suiting individual physical constitutions. For example, skin eruptions all over the body.

Inflammation of the oral mucosa, which spread like liverwort from tongue to gums. Not just a sense of lethargy, but a true loss of energy from the entire body with a prolonged period when one could not even chew.

If there was one person who took on all these symptoms, it was Takako. Though slender, she was not necessarily delicate, yet she succumbed to each symptom.

“I’m a superior guinea pig,” she would say, as she spoke of a new symptom each time I saw her.

Around two weeks after the bombing, Takako began to lose her hair. She would grasp some hair, cross her heart with a prayer, “Please stay,” then pull it to see.

The strands that she held in her hand would come off just like that.

She became bald almost instantly.

With no distinction between face and head, she looked unfocused. The area from the corners of her eyes to the back of her head looked like an extension of her face, and when she talked, only her lips looked oddly soft.

Takako covered her head tightly in a scarf so that no more hair would fall out. This was during an era in which there was a shortage of goods. No such luxury items like Western-style scarves were around after the war. As a substitute she used a furoshiki cloth,1 the last article her mother had refused to part with and kept in a corner of a chest of drawers.

It was made of high-quality silk, a bright vermillion color that burst in the light. No matter how high in quality, it was still a furoshiki, making Takako feel that she was wrapping her head in it rather than wearing it on her head.

When walking through Hamamachi, it was easy to spot her approaching. The contour of her head showed clearly, suggestive of a small watermelon wrapped in cloth and indicating that her hair had fallen out.

“I can tell you have no hair left,” I whispered to her frankly.

“Oh yes, I still have some. See, take a close look,” she said, taking off the furoshiki.

Heedless of being out in the streets, she extended her head before my eyes. “See? There’s some, isn’t there?” She waited for my answer with great seriousness.

In the sunlight, I noticed gray ciliation that resembled mildew on rice cakes. It wasn’t something that could be called hair, but I answered, “Yes, there seems to be a little.”

The same ciliation stuck to the reverse side of the furoshiki as well, but I pretended not to notice.

Takako, too, looked indifferent.

“You’ll lose yours soon, too. It can’t be that you’re the only special case,” she said, as she pulled my braided hair.

It didn’t come off. Looking at her fingertips that pulled at my hair, she said, “It’ll fall suddenly,” repeating that it was impossible for only one person to be special.

Next, Takako began to bleed.

A large amount of radiation causes problems like kidney disorder and the delayed development of bones, but it strongly affects reproductive organs as well. The majority of male inmates who were bombed at the Hiroshima jail were found to be impotent.

With women, many cases of sterility were reported due to the death of reproductive cells. The percentage of miscarriage was also high.

The greatest disturbance, I heard, was seen among growing children. It was not rare that menstruation began suddenly after the bombing, or that bleeding did not stop.

The majority of people, however, stopped bleeding within a month. Takako was an exception. Right after the bombing, while fleeing near Peace Park, she passed water. Her urine was fresh blood.

It was not bloody urine, but bright red blood.

Not one hour had passed since the bombing.

Looking at the blood soaking into the rubble, she first mistook it for menstruation. She was not shocked because she had menstruated previously, but this was not that; it was clearly discharged as urine.

One week later, menstruation began. One week passed, two weeks passed, and there was no sign of it stopping. The amount was also more than usual. The condition lasted for three months, never skipping one day.

She took to bed in diapers. Purple spots the size of red beans broke out all over her body. Her fever ran above 104 degrees. “She’s going to die,” the rumor gradually spread.

Around that time, a cure using the patient’s own blood began to be talked about as the most effective method for blood troubles caused by a-bomb illness. This meant hip injection of the patient’s blood mixed with a certain medical liquid to avoid coagulation. Takako seemed to have received this treatment.

Among my friends was one whose menstruation lasted as long as six months. She had the same symptoms as Takako, and the bleeding never skipped a day in those months. An amateur, I cannot tell if one can call six-months of bleeding menstruation. I simply call it by that name because it took the same form.

That friend, the only daughter of a doctor, also received blood transfusions. According to her story, 20 cc of blood that was of a completely different type than her own was injected during one session. This was repeated three times.

Even an amateur knows that the transfusion of a different blood type leads to the rejection of heterogeneous protein and death.

“You don’t say so,” I said, incredulous.

“Well, listen then. My relatives are all doctors. But they thought this the only way, and used a treatment that even amateurs laugh at.”

After the transfusion, she ran a fever over 104 degrees and a violent quiver assaulted her entire body.

It seems to have been a form of shock therapy, a kill-or-cure venture, grabbing death backwards as a weapon against death.

My hair did not fall out. But, as Takako said, the a-bomb provided no special exemption.

One morning, I found a red spot on my wrist. It was just an ordinary spot. It held liquid at the tip, which, when I scratched it with a fingernail, burst open with a faint, yet powerful sound. That powerful burst on my mind, I put my arm out from the blanket to check on it the following morning. Around the spot, new spots clustered like Deutzia flowers.

I carefully crushed them with a fingernail.

Constitutionally, I was not prone to suppuration. Even if I scratched my skin with a fingernail, a reddish black scab would form by the following day and the wound quickly healed. I crushed those spots assuming the usual outcome, but they gradually suppurated, losing their shape.

This was a kind of rash from radiation, limited to areas of skin that were directly exposed to the air or covered under black clothing. In my case, it occurred only on my arms and legs. When one spot began to rot, the heat of the wound seemed to speed up the suppuration of other spots, which too went rotting, viscous.

When I walked, bloody pus fell on the tatami. My mother wiped it clean with a rag if she found any, but my sisters kept pointing out more, saying, “Here too, look, some over there.”

My mother boiled a well-worn indigo kimono bathrobe in a large pot, split it into 5- or 6- centimeter-wide strips, and, in place of bandages, dressed my shins in them. Kimono patterns showing here and there, I was a straggler no matter how I looked at myself. “White Tiger!” Schoolgirls my age jeered in unison when I walked through town to commute en route to the hospital, referring to the boys’ troop of Aizu Province that was routed in the Boshin War.2

“Tell me which grade, which class you’re in and who your homeroom teacher is,” said my mother, who accompanied me, angry enough to report them to the teacher.

It felt better to expose the wounds than to protect them under bandages. The wounds pulled in the wind and hurt, but it was refreshing because the wind lifted the heat from my skin.

On days when the wounds held more heat than usual, I would spend the entire day without bandages under a room-size mosquito net in the well-ventilated living room. If I was inattentive, flies laid eggs on the wounds. Many green-bottle flies flew around the mosquito net.

In that condition, I experienced my first menstruation.

I wondered if mine, too, like Takako’s, might refuse to stop. I had no idea whether its coming meant normal development or was an unexpected result of the a-bomb illness. Each time a clot of blood was discharged, I felt it in my as yet narrow pelvis, and each throbbing flow of blood took something away from my body. I felt insecure.

I crouched in a corner of the room holding my lower torso in both arms. Unfortunately, both my older sisters, who might have shown me what to do, were out. My mother had gone to nurse hibakusha housed in a nearby elementary school.

I traced my memory of a lecture we received soon after entering the girls’ school during a childcare class.

The female teacher, dressed in hakama, explained menstruation to us while pointing at an anatomical chart with a bamboo stick. I had learned the lesson by heart because the topic was to be covered in the trimester-end test, but nothing was of help in an emergency. Listen, she said, menstruation is there to tell you that you are physically ready to have a baby. This portion of the lecture had made me feel cheerful.

If things were as she said, the beginning of my menstruation was a healthy sign. I had no reason to feel insecure. With the menarche, my a-bomb disease may have taken a course for recovery.

I waited for my mother’s return. She would be pleased to hear the news.

She had a simple-minded side and always knew how to interpret things to her advantage.

Would my daughter die today, or tomorrow? This was the question on her mind as my mother spent her days measuring my lifespan. She would take her daughter’s menstruation as proof of her health. Even happier than at the time of the first menstruation of my sisters, who had grown up uneventfully, she would certainly steam rice with red beans, a celebratory dish that had become customary at home. Because we’re celebrating, she would say, take out the precious store of black market rice from the closet.

We must get some Queen Rose, she would say in the affected standard dialect she had used when we lived in Shanghai, and rush to the drug store herself.

Queen Rose was the brand name for safety napkins. When I was an elementary schooler, I often ran on the streets of Shanghai to a drug store to buy Queen Rose for my sisters and mother.

Come here for a second, my mother would beckon me to a corner of the room and whisper in my ear: Go get some Queen Rose. Unlike usual, her voice then carried a womanlike tenderness.

Sensing from the private tone of her words a woman’s secret, I ran along the streets of Shanghai with short breath at those times, if never on other errands.

Queen Rose came in a crimson cardboard box decorated with the image of a white rose on the chest of a princess. I never saw the contents.

Let me see it, I would say with a conscious gesture of sweetness as I handed over the box. “Mother, how indecent can she be,” said my sisters, glaring at me, their glares full of delight.

“It’s too soon yet,” my mother would say in a high-pitched voice as she joined their merriment. “I’ll buy you some to celebrate when the time comes,” she added.

Before that time came, I sniffed out what the contents might be from how my sisters appeared.

When I could no longer contain myself I would open the talcum powder scented crimson box alone in a room—I felt as if that would be enough to make me a beautiful adult.

The day of celebration that my mother had promised came when my skin had begun to rot with a-bomb illness.

Made of rubber gently touching rubber, like yuba, the thin film that forms on bean curd in the tofu-making process, Queen Rose held two meanings for me: a sign of passage to beautiful adulthood and, more than anything else, a healthy body capable of giving birth.

I’m not Takako, I told myself.

I pulled out a cottony blanket from the closet.

In those days, rationed blankets were woven mostly of cotton with waste yarn mixed in here and there. The texture was coarse, and pulling it with a little force made it uneven. When it rained, it sucked moisture so that it felt too heavy to handle.

I sat in the corner of the room, firmly wrapping my lower torso in the heavily moist blanket to keep blood from flowing down from my thin summer clothes.

When she returned in the late afternoon from nursing, my mother found me wrapped, in mid-summer, in the blanket.

“Do you have the shivers?” she asked in Nagasaki dialect, as she brought her lips to my forehead.

She always felt my temperature with her lips. No, I said, confused, pushing her chest away from me. Menstrual blood develops a strong smell when it sits. Each time I smelled it, I felt as if I were becoming stained. I felt awful, this being my first experience. A sudden shyness assaulted me. I didn’t want anyone to know.

But my mother was too sensitive to miss what was happening.

“It can’t be,” she said as she looked at my body, and asked directly, “Your period, isn’t it?”

“No!”

I lied on reflex. The expression my teacher used in class, though equally a physiognomic term, had a wise ring that celebrated women’s health that my mother’s lacked. It washed away in a twinkle the scent of talcum power that I had cherished carefully until that day.

“Buy me Queen Rose, please?” I asked my mother. She bluntly replied that there was no such thing nowadays. “At such a time, of all times,” she added, knitting her eyebrows.

She couldn’t determine whether her daughter’s menstruation meant normal growth or was due to bleeding caused by the a-bomb disease. And because she couldn’t, she was in a bad mood. On the brink of life or death, her daughter may have begun preparing for womanhood. It seemed that, as a woman, my mother had an aversion to the body moving ahead with the instinct to birth in the absence of all else.

I missed my “genderless” girlhood. I remained seated on the tatami floor of the room, now dark, thinking I would much rather that all the blood flowed out of my body as with Takako.

“Hey,” the bartender called.

When Takako looked over, he said, “There’s a guy who’s interested in making some money.”

“Is he young? How’s his build?”

“Perfectly O.K.,” he rounded his fingers behind the counter.

“I’ll think about it before I leave, so hold on for a bit,” Takako stopped him as he put his finger on the phone dial.

“What’s O.K.?” I asked Takako.

“What?” Takako asked back, then answered without hesitation, “Oh, just a male.”

“A male? A human male?” I asked stupidly, recalling the rumor I had heard from K the day before.

K had eagerly told me, eyebrows knit, that Takako regularly bought young, healthy men for their bodies. Impossible, I laughed at the rumor, which seemed much too wild. Was K’s story true?

As I remained unable to discern Takako’s intentions, she looked at me and grinned broadly.

“She’s liberal with her money,” the bartender jested, shrugging his shoulders.

Takako married in 1957, at the age of twenty-eight. I heard it was an arranged marriage. Arranged marriages were rare among hibakusha. No one would choose to marry a woman with a bad background. At the same time, we ourselves did not much feel like waging our lives on marriage. Rather than considering marriage as something that would last throughout our lives, we rather tended to view each day as the beginning and end of married life. This was the way to live without disappointment for those of us who never knew when our illness might relapse.

Takako did not seem to have any particular hopes for marriage either.

Her partner, from Kansai, was a part-time college instructor. He was five years older and, of course, was not a hibakusha.

At their meeting held with marriage in mind, Takako took the initiative to announce that she was a hibakusha and related all the symptoms she had then.

At each previous such meeting, her parents had tried to suppress the history of her exposure to radiation so as to smoothly bring about the marriage. Because the arrangement had fallen through a number of times due to an agency’s investigation that revealed her past, her parents had tried even harder on this occasion.

The man who later became her husband heard her story through and said, “It doesn’t matter at all, to me at least. The war damaged more or less all of us who lived through it. You and I are fifty-fifty in this sense.”

Her husband-to-be seemed to interpret her story as a reflection of her victim’s mentality, covetous of sympathy.

Her parents thought him broadminded and concluded the proposal, perhaps too rashly, with an offer of a small, sunny mountain grown with Japanese silverleaf and one of the old houses they owned.

The man who became her husband was engaged in arcane academic research that involved digging ancient earthenware up from the dirt. He put lost time back into shape, which was like fitting puzzle pieces into empty space. Perhaps due to the nature of his work, he was not too particular about daily life.

Takako continued to run a slight fever of 99 to 100 degrees. With a husband well suited for a woman of delicate health, who left her alone as he thought fit, her marital relationship was ideal. She neither loved nor was loved.

In their second year of marriage, Takako’s a-bomb illness recurred in the form of breast cancer.

It was a sultry, warm day during the rainy season, when the sun broke out. She suddenly felt like washing her hair and took a bath.

Partly due to having lost her hair after the bombing, Takako was obsessed with it. Her hair was long because all she did was trim it, hardly ever using scissors for a real haircut.

Combing the freshly washed hair with a boxwood comb required a fair amount of strength from her fully extended arm.

As she combed with her left arm, she felt some tension in the muscles on her chest. She changed the movements of her arm, but the tension was still there. On probing the breast with her fingertip, she came upon a stiff mass the size of a rice grain.

Each time she took a bath, she examined herself with her finger. There was no pain, but the stiff spot was always there in the same place. She suspected cancer.

She was only thirty. Pouring warm water over herself in the bath, she saw drops of water trickle down her skin. Her skin was lustrous, even ruddier with life than when she had been a girl.

Takako trusted her youth just as any other woman would. Afflicted by the a-bomb after effects, she still believed in her physical youth.

The stiff spot fattened. By now she could feel an unevenness under her fingertips when pressing it. A pale pink hue developed on the surface of the skin. It was just a growth after all, Takako thought with relief.

The absence of pain worried her, but she knew cancer would play no such tricks as drawing attention to itself by adding color on a swelling. Suppose it were cancer. Given the fact that a fair number of days had passed since the rainy season, Takako would already have been dead.

Still, the absence of pain was ominous. When she thought about it, she realized the color was much paler than that of other growths. It didn’t come to a head with pus, as would an ordinary growth. Somehow, just the left nipple looked dark and felt strained. Feeling uneasy, after her bath Takako showed her skin to her husband: “Take a look, it can’t be cancer, can it?”

Her husband took a quick look at her skin, fresh from bathing, as if stealing a glance at that of a stranger’s.

“The possibility could exist,” he said simply in his usual formal, standard dialect.

“When breast cancer is found too late, it’s due to the husband’s negligence, I hear. I suppose we can’t help it if our relationship is suspect,” she said half in jest, trying to arouse his interest.

“Please don’t joke about it,” her husband said, seated straight without a smile. “One should manage one’s own health. Even between husband and wife, it is each person’s responsibility. Not only that, in the first place I never wish to see a wound on another living person,” he said.

The cancer continued to grow unhindered inside Takako’s tender chest.

Cancer that has nested in a young body grows surprisingly fast.

Takako was wrong to have trusted her young body.

Partly due to the hot weather, which reached 90 degrees that day, she felt sluggish and stayed in bed all day but then rose to prepare dinner.

Putting her hands on the kitchen counter, she looked up to turn on the electric switch, when she felt the back of her head grow weightless and her knees buckle. About to fall backward, she unconsciously bent forward to support herself on the counter.

At that moment, she banged her chest. It was a nasty blow, right against the corner of the counter, on the growth of her left breast.

She heard the sound of bursting flesh. Then came the raw, warm smell of ripe fruit.

Takako pressed her breast with both hands. Under the swaying light, bloody pus slipped through her fingers. It had been this rotten, she thought as she measured the amount of blood in both hands, and momentarily regretted having left it alone for so many days.

Be that as it may, she also told herself that it wasn’t much compared to the amount of her earlier bleeding, which had continued for three months.

Takako heard the voices of her husband and neighborhood women; the siren of an ambulance went off, and she was taken to the hospital. She was carried directly to the operating room, right on the stretcher, and the affected breast removed.

While she was dozing after the operation, her husband informed her: “They say it is cancer. I thought you would want to know.”

Takako was not so frightened. It can’t be helped, she thought. Besides, she knew how the a-bomb behaved. It attacked unyieldingly in waves over months and years. Without exception it took what it intended to take.

Where next? — she wondered, looking at the white bandages tied around her entire chest.

She could no longer raise her left arm. Nor could she reach her back. Her freedom of movement was restricted, as if her arms and torso were sewn together.

I’m going to lose my freedom step by step over the years, Takako realized.

As he read, her husband spied on her awkward movements. He did not say to her, “You must feel inconvenienced.”

He merely peered at her steadily.

“I can’t move, please help me” — she wished to say this, honestly disclosing her difficulty, for that would have helped heal her feelings when she was easily depressed. But when she tried to talk to him, he quickly shifted his eyes back to his book.

“When things are hard, I make it a rule to recall the day of the bombing,” she told me. “If I think of that, I can put up with anything.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “But how lonesome that is.”

Takako just nodded and then said, “Look, it’s gone.”

Abruptly stretching her right hand across the table, she grabbed my wrist.

“See? You can tell it’s gone,” she said as she pressed my fingertips to her left breast.

“It’s there, of co-o-ourse,” I jested, not knowing what to do, in a tone of girlhood exchanges. Takako laughed aloud.

“You often lie to me,” she said. “When I lost my hair, too, you lied and said ‘It’s there.’ Look, feel it carefully. It’s just sponge.”

Pressing my fingers now to her right breast, she made me recognize the difference.

I pulled my hand back unsympathetically. “It’s okay if it isn’t there,” I said almost angrily.

She shook her head and said, “It’s not okay.”

How can men take breastless women seriously?— This was what K had said to me yesterday, jiggling with pride her breasts, which she said fit only an American B-cup brassiere.

The reason that Takako bought men with money, K explained, was because she had to compensate them for the breast that had been surgically removed. Here was a woman paying a man to hold her, K said drolly.

“But why does she buy men?” I insisted on knowing.

“How do I know? She was fond of men,” K replied nonchalantly as she left, “from long ago.” It was hard for me to think that this was the only reason Takako bought men.

“May I have some ice?” Takako asked the bartender and pushed her bottle toward me, saying, “You can drink, too, can’t you?”

I poured a few drops into my coffee.

Recalling the fresh-baked French bread I had bought at Hamamachi, I asked the bartender if he could fix ham and eggs. An item not on the menu came with an extra charge, he pointed out and asked if it was okay.

“Put it on the house,” Takako said in a loud voice. There were no other customers in the store. Straining my ears, I heard the festival drums of Suwa Shrine mixed in with the noise of the town.

“Are you going to display that doll?” I asked, pointing at the paper bag at the edge of the table.

“I have more than twenty, but I don’t mean to display them. I store all of them wrapped in paper in a wooden box.”

“Why do you buy them if you don’t display them?”

“I want them to be cremated with me when I die. They are my burial figurines,” she said, pinching the paper bag between her fingers.

The bartender brought over ham and eggs, skillfully fried to half done, along with thick-sliced cheese.

Takako picked up a slice and bit into it with her front teeth, and, leaving an arch-shaped impression, put it back on the glass plate.

Breaking off a piece of the French bread, I handed it to Takako. She gazed at the piece, still warm, for a while.

“Thanks,” she said in a small voice. “I wonder how many years it’s been since I felt this relaxed. It seems I have struggled and struggled, squaring my shoulders. I feel like sleeping restfully in the arms of someone who knows every bit of me, doesn’t ask for any compensation, and holds me without saying anything.”

Takako knew that spot bleeding of unknown causes was associated with breast cancer. Sooner or later, something would find its vent in that little wound and burst out. That something, she knew, was already in progress.

“I haven’t even told my mother. There’s stiffness in my right chest, too. Look, it’s here,” she said without expression, placing my finger on the stiffness and rotating it around the spot.

“This is definitely cancer,” she said. “But I’m not going to die so easily.”

In August, one year after her operation, Takako became pregnant.

“What?” I asked back when I heard of it. The effect of the post-operation X-ray treatment on the fetus was a matter of concern, but perhaps it was all right because we hibakusha have more than enough immunity against radiation.

What was more unexpected was that her husband, who had coldly announced that he did not wish to see wounded bodies, was willing to hold his wife. I had automatically assumed that they hadn’t consummated their marriage.

Takako was ecstatic about her pregnancy. Because of her girlhood bleeding lasting three months, she had thought herself infertile. She rejoiced at her lean body now growing rich with fragrance.

She told her husband the doctor’s diagnosis in detail.

|

|

| Hibakusha mothers and children | |

As usual, he listened while reading, then asked, his eyes rounded, “Can you be with child?” He added: “More importantly, I am surprised that you intend to give birth. In the first place, you are a hibakusha. Second, you are the one who explained to me how radiation would affect the genes.”

She didn’t have to be told. She knew that. Knowingly, she rejoiced in her pregnancy. Amidst all those grim symptoms, the smallest sign of health was a delight she could not resist.

“There is a possibility,” she spoke formally, switching to standard dialect, “that the baby may be deformed. Therefore you say it is not right that I give birth, is that so?”

“It’s not a sentimental matter of good or bad. You showed me a photo of a microcephalic child exposed to radiation. I simply saw it as one example of what can happen, but I cannot accept the same for my child. Not just my own child’s, but any deformity that can be prevented should be rationally checked ahead of time. Wouldn’t you say it’s our responsibility to leave superior people for future generations?”

“A married couple,” Takako noted, “is a strange thing. Even if you don’t love the man that much, if you start a life together, you feel like building something together. Give birth to his male child, foster, and build. Build, or reach a certain point of building and let it fall apart again. I don’t know exactly what, but anyway, you feel like having something in common to foster. Marriage and home are something like that, aren’t they?”

Takako sipped a little whiskey.

“Is there a single microcephalic or otherwise deformed child among your classmates or mine? I haven’t heard of any,” she said.

I hadn’t heard of any such examples, either. Rumor would spread right away if a child were born microcephalic or had any trouble with the functioning of limbs and body.

It may be that a child with physical deficiencies, even if born, dies soon afterward due to its natural fragility. The rate of death within the womb must also be high. Disgraceful stories such as these would be buried from darkness to darkness. However, rumors of concealment tend to spread.

Judging from the fact that not one story existed, it would seem that none among us had given birth to a disabled child that would breed rumor.

Takako’s husband one-sidedly enumerated her shortcomings, but there must have been some risk on his side, too, of causing deformity. Statistically speaking, such a risk exists at the rate of one in fifty healthy couples. One could not say it was Takako’s responsibility alone, if by one in a thousand chance a disabled child were born.

She restrained her desire to protest. The disadvantage, after all, was larger on her side.

“I would like to have the child,” she told him.

“Can’t you please think about the arrival of a healthy child rather than worrying about a deformed birth,” Takako asked her husband.

“I don’t think I’d like that,” he declined plainly. “You can’t give birth by way of experiment. You are talking about a life.”

Takako acquiesced to his words. The fetus was in its fifth month.

This is almost like a premature birth, said the doctor, who feared for the mother’s health and encouraged her to carry the baby to full term.

“Because I’m a hibakusha, I worry about deformity. I was under treatment for a-bomb disease till recently,” she explained and added that this was her husband’s wish as well.

After the operation, the doctor said to Takako, “Let me tell you this for future reference. It was a healthy baby boy, a little larger than average, with perfect fingers and toes.” He added encouragingly: “Next time, give birth with peace of mind instead of worrying about unnecessary things.”

“I killed a healthy baby,” she told her husband after reporting every word the doctor had said.

“So you want to judge me,” he said. “Then why didn’t you disregard my opposition and have the baby? You were worried, too. You feared the misfortune of one in ten thousand cases, just as I did. Neither of us had the courage to accept a mentally or physically disabled baby as our child.”

“It’s not the life of the baby that was an issue for you,” he continued. “You wished simply to live freely without problems. All you wanted was a ‘perfect’ child as a component of the family, a component necessary to a healthy family life like a TV set, an air conditioner, or a car. You have no right to criticize me; we are equally to blame.”

“Before I realized it,” he added, “I was as involved as you in your a-bomb ‘disease’ and found myself looking at our unborn child with the mentality of a victim. I was made to see clearly the fragility of reason. I feel miserable. I have had enough of former soldiers begging on the train, and I have had enough of your a-bomb ‘disease.’” With this he left the room.

Takako recalled his words from their first meeting: all Japanese were scarred by the war. Whenever he wished, she felt, he could promptly distance himself from the scars of the war. Her parents, too, had found her a husband and then gone away. Takako was always left just as she was. She was left in the midst of raw wounds that had lasted since August 9.

Takako and her husband divorced. Their marriage had lasted four years.

After the abortion her right breast swelled up, blue veins rising to the surface. When she squeezed the breast, it released yellow milk.

She felt pain even on the left side of her chest that had no breast. As her husband said, it was not a matter one could gloss over. For their aborted child, there was a tingling even in the taut-skinned part of her chest. Wishing to make what little atonement was possible, she began volunteer work with handicapped children.

“Your husband’s great,” Takako commented. “I’m impressed that he let you have your baby. Didn’t he say anything?” she asked, pouring her third glass of whiskey amply to eight-tenths full.

“Is it okay to take that much?” I asked, concerned.

“Though it’s a banal thing to say, this disinfects the rotten body,” she joked, drinking half the glass in a single gulp.

Her words make me think that my husband may indeed be great. He approves of most of what I say and do.

His assent may come from disinterest, however. In a way, he seems to calculate the inconvenience of placing restrictions on his own neck by putting fetters around his wife’s.

He showed no interest in his unborn child. He had no unnecessary worries about his wife being a hibakusha. Nor did he ask me to go through with the pregnancy.

When I informed him that I seemed to be with child, he groaned “Oh” with surprise, eyes on my flat abdomen.

I told him of my insecurities. “I wonder if the baby will be strange.”

“No telling,” he said. He took another look at my abdomen and said, “I feel strongly that the ‘fellow’ inside of you belongs to you. No, it’s my child, and I’m not arguing about that. Frankly speaking, I feel like you should discuss it with the fellow inside of you.”

In other words, he was telling me to ask if the fellow inside of me wished to be born. Oh, I see, I thought, comprehending my husband’s thoughts.

In short, he left it entirely up to me to keep the baby or have an abortion. Because I thought it our child, I had wanted to know his intentions as its father.

I decided to keep the baby. I cared for the little life that was doing its utmost to be born, regardless of its parents’ speculations. In order to give birth to as healthy a child as I could, I began putting things around me in order. Fearing prenatal influence, I put together the a-bomb related photos on my desk and placed them in a large envelope.

I closed it with adhesive tape and wrote “sealed” with a red magic marker I had bought for this act of sealing, which I viewed as a matter of celebration.

I would not unseal this envelope until the baby’s birth. If there were such a thing as prenatal influence, I would seal my past along with these photos and raise my child in an unstained womb.

I placed the sealed envelope on my desk and said to myself: This does it. I remained gazing at the yellow envelope for a while.

Among the photos I put in the envelope was one of a little girl in a padded air raid hood, eyes and nose indistinguishable because of burns. Whatever might have happened to her mother, the girl sat all alone amid the rubble. Her face was expressionless.

I put the photo of a mother’s charred body into the envelope, too. A baby was by her side, charred uniformly black just like its mother, round eyes open and hands firmly together—I found myself going over in my mind every one of the photos I had put in the envelope.

Those photos came back to me all the more vividly now that they were sealed in. Not only that, the tragic scenes in them were the very scenes I had directly witnessed a number of years ago. Memory and photos mingling, I had an illusion that the children sealed in the envelope were scratching the envelope, making dry sounds.

I pushed the envelope into the space under a chest of drawers. I trapped it firmly under the chest so that a charred baby could not break free and crawl into my womb.

Labor began at midnight on a cold March day. I woke my husband at midnight. “Perhaps you can wait till morning,” he said.

Wait? Wait for what? Did he mean put up with the pain till morning, or hold the birth till morning? Was delivery that easy to maneuver? Was he by some chance confusing delivery and excretion?

He seemed to forget that the fetus came to life with a will of its own.

The labor pains grew intense and occurred at shorter intervals.

“Please take me to the hospital,” I asked.

He rose and sat on the bed. He lit a cigarette and took a savory puff, but immediately crushed it out, looking displeased.

“I have to go to work tomorrow.” Then he added, “On the whole, you lack planning. Didn’t you even make sure which day and time to expect delivery? If this is pain that meets the expectations, I will of course take you to the hospital. But if you are simply complaining about pain, all I’ll do is catch cold to no gain. It’s bad for your health, too.” That said, he pulled the comforter over his head and went to sleep.

The clock showed it was past midnight.

I began to make preparations myself. I wrapped bleached cotton diapers that I had sewn and two soft gauze undershirts in a furoshiki. I also put in a pair of booties I had knit with the finest yarn, right and left different in size by one quarter inch.

Would these uneven booties fit its little feet? Wouldn’t the baby dislike these unshapely things that looked like small rice-bran bags used for scrubbing in the bath? I felt somewhat cheered, imagining the sight of the baby not wanting them and wrinkling its red face.

I walked along the midnight road by myself. When the pain came, I crouched by the side of the road and waited till it eased. Although it was the season when cherry blossoms would soon bloom, frost was on the road.

At 6:20 in the morning, I gave birth to a boy.

“Congratulations! He’s on the small side, but plump. He’s nourished enough to have creases on his thighs,” the doctor said, raising high in the morning sun the baby that was still covered with lard-like mucus.

I asked to see the baby’s face. It was red-faced with black, lustrous hair. Eyes firmly closed, it seemed to be resisting the first sunlight with its entire body.

I was relieved. My child was not expressionless like the children I had sealed away in the envelope.

Past seven o’clock in the morning, my husband came to visit me at the hospital after breakfast. He forced open the fingers of the child’s tight fists and counted them one, two, with his own thick fingers. He even pulled its feet drawn into the baby robe and counted the toes. When he finished checking to see if all the fingers were there, he looked at me with a smile.

“I wonder if he looks like me,” he said, bringing his face to the child’s cheek. Then he lay stretched out. “I think I’ll skip work today!” he said happily. Soon he was asleep, snoring loudly.

I resented his counting the child’s fingers. Every parent would naturally check them, yet it bothered me.

If the baby had had defects caused by the bomb, my husband would never have asked if it looked like him. As the fellow within you belonged to you, so it still belongs to you after birth—this might have been his thought.

There was a boy who was microcephalic due to the a-bomb disease. His I.Q. was low and he was mentally retarded. The mother, who was pregnant at the time of the bombing, lived near Peace Park where Takako is now consecrated. It was an area where nearly everyone met instant death. At the moment of the bombing, the mother was in a shelter, rearranging clothes and emergency food.

All the other members of her family who were inside the house died instantly.

The boy had an extreme speech disability and managed just barely to utter sounds. His arms and legs were round like wooden pestles. Finger-like joints were attached here and there, but had no function as fingers. From early childhood he had ill-defined convulsions of the entire body. They were ill defined simply because they could not be explained medically; in fact, they were caused by exposure to radiation while inside his mother’s womb.

When he grew to twelve or thirteen, he developed sexual desires. Not knowing how to control himself, he threw himself on his mother as led by his instincts. The mother tied his waist with a rope and leashed him to a pillar in the living room. He howled like a dog, trying to break the rope with his teeth. Upon consultation with the doctor, the mother had the boy’s testicles removed.

He became a “good” boy with dulled responses, a quiet boy who would do no harm to healthy people.

In the spring of his fifteenth year, he was overcome by intense convulsions, and died after quivering all day long. The only human-like response the boy had ever demonstrated was his unrestrained sexual desire before the operation.

“Would you have had him operated on if he had been yours?”

“No,” Takako replied instantly. After gazing awhile at the amber-color liquid in her whisky glass, she continued, “I wouldn’t have had him operated on. We would try leading a life, however bloody, parent and child together. Now I think that way. I think often about the day of the bombing. I was really happy I survived. I wished to survive even if I lost an arm.”

After the abortion, when she heard that the child was without any physical defect, she regretted the little life she had given up. For the first time then, she realized clearly what she had wanted. She had wanted a human baby, whole of limb and meeting ordinary standards, and she didn’t need her husband to tell her that.

“Just suppose the aborted baby had defects. I would probably have felt relieved thinking I had done the right thing. I wouldn’t have regretted its life,” Takako said.

She told me about mentally and physically disabled children. Twenty-two or three children are housed at the place where she works. They include second-generation hibakusha and those who aren’t. There was one who was Mongoloid. Five or six years old, the child could not even eat properly. Nor did the child have the desire to eat. Takako was drawn to the child sitting in the sun in the hallway.

Each time she visited the place, she found the child sitting in the same spot, staring vacantly.

Takako bought a little bouncing ball decorated with red thread. Seated face to face with him, she threw it at him to see if he would respond. His eyes remained directed toward her face as vacantly as before.

She went to fetch the ball that had rolled away and threw it at the child. Repeatedly, she threw and fetched the ball.

She threw it at different places on his body, at his hands or directly at his chest, trying to make him catch it somehow. One day, after a few days of having made this effort, the child smiled when she threw the ball.

The child had been taking note in a corner of his heart. While observing Takako over the days, he had been taking in something.

“Fine for healthy children and handicapped children to be as they are,” she said. “The mixture is what humans are.”

If the value of life were forgotten, August 9 would be meaningless to her.

Suddenly, she burst out laughing looking really happy. “I’ll tell you about my only rebellion,” she said as she brought her face closer to me.

She kept a stray cat. She fed it only nutritious dairy products. The cat grew robust and fat. To bring it up as an agile wild cat, she hit its tail if it sprawled in the sun. The cat learned to be as sensitive as a dog to footsteps. It ran before Takako approached.

As Takako wished, the cat grew like a puma. It had nasty eyes. If human, it would have been the type to be tailed right away by the police.

Whether cheese or ham, Takako threw the food at it. It jumped agilely to catch it in its mouth. It had black, shiny hair. Moreover, it was a male. It roamed freely, impregnating female cats in the neighborhood.

A woman from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals came to ask that the cat be sterilized. Takako paid no attention.

“Cats live as cats should,” she laughed delightedly.

“What do you say? Shall I make the phone call?” The bartender asked.

“Yeah, try calling.”

She winked at me as she poured another whisky, already having consumed several glasses.

“Call—a man?” Aware of the bartender’s presence, I whispered my question into Takako’s ear.

“A man to buy with money. He’s strongly built, that’s all,” she said without self-consciousness.

“What do you buy him for? Do you want a man?”

“Want…maybe it’s a little different. I wish to hold young men, imbibe some of their energy, and make sure of my own life. I want a solid sense of being alive. There’s nothing else in my hands.”

“You’ll get pregnant. Are you going to have another abortion?”

“I’ll have the child. No, it’s not sacrilegious; I’ll have the child of my own free will. Fine if it’s deformed. I’ll let it live in my stead.”

There are plenty of men. I commented with common sense. It’s not recommended to buy a man with money. Takako laughed, “You only stand on your feet and look upward, so you talk like that. Crawl like me and set a red eye on the ground.”

“You can very well see human essence or whatever it’s called,” she said, slapping her left breast. “Who would take me seriously? As you know, rumor flew after the bombing that I was dying. But I was thinking there would still be something in store for my future, it would be a waste if I died just like that. Now, though, there’s nothing left. Unless I test myself against another person’s strength, I don’t even have a real sense of being alive; still, I want to remain alive.”

It’s one year since Takako died. After our last meeting, her right breast was removed. The wound left after the operation rotted, even the area sewn with thread.

Her whole body, I heard, was nested by cancer. Infused with the body fluids of young men, the cancer cells might have affected Takako all the more energetically.

In the letter she sent me right before her death she wrote, “I’m already exhausted.” Cancer made the gesture of slowing down for a year or two following an operation. Each time that happened, Takako saw some hope. And she was betrayed.

“It’s too painful,” she wrote.

Her symptoms indicate the course I must trace. She has carefully guided me along the way hibakusha must follow. Takako has already lived enough. Her vitality still surprises me.

What I dread most is not being able to die easily.

I feel relieved that Takako died. Even in the worst of situations, I can trace that passage. I burned Takako’s final letter in the yard. Going out to the yard after the rain, I collected moistened fallen leaves and placed the letter on the heap.

I took from the glass case the clay doll I had bought with Takako at Hamamachi, and put it on the letter. I emptied the entire contents of an economy size matchbox around the body of the doll.

I set fire to them. The red heads of the match sticks flared all at once.

The clay doll burned, mouth wide open.

I picked up a small rock from the ground and crushed to pieces the corpse of the clay doll, charred black.

“Takako’s burial figurine,” I muttered as I scattered the pieces on the dirt.

Nearly twenty clay dolls still remain in my glass case. These are my burial figurines. The wailing clay dolls are called “Masks of Whatchamacallit.”

| Nagasaki Memorial Ceremony, 2015 |

This novella was originally published as Nanjamonja no men in 1976. This translation is based on the version that appears in Hayashi Kyōko zenshū (Collected Works of Hayashi Kyōko), vol. 1 (Tokyo: Nihon tosho sentā, 2005), 415-48. This translation was first published in the Asia–Pacific Journal on December 12, 2005. It benefited from the editorial assistance of Miya Elise Mizuta and Lili Selden. Kyoko Selden’s translation of From Trinity to Trinity was first published in the Asia–Pacific Journal on May 19, 2008.

Notes

Furoshiki is a cloth used for wrapping packages, such as clothes and gifts, for transporting them.

The Boshin War refers to a series of battles leading to the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of direct rule by the emperor. It began in the first month of 1868, or the year of boshin in the sexagenary cycle, and ended in the sixth month of 1869. Byakkotai, or the White Tiger Brigade, was a corps of a few hundred youths, organized in the third month of 1868 by the pro-Tokugawa Aizu Province (now part of Fukushima Prefecture) to resist the forces of restoration. It was decimated by the Imperial Army. Twenty survivors made their way back to Wakamatsu Castle, the Aizu stronghold, but committed suicide on a nearby mountain. The group became a popular symbol of loyalty, determination, and courage.