Abstract: What is the role of apologies in international reconciliation? Jennifer Lind finds that while denying or glorifying past violence is indeed inimical to reconciliation, apologies that prove to be domestically polarizing may be diplomatically counterproductive. Moreover, apologies were not necessary in many cases of successful reconciliation. What then is the relationship between historical memory and international reconciliation?

Japan, many people argue, has a “history problem.” Observers lament Japan’s half-hearted or contradicted apologies for its World War II atrocities, arguing that Tokyo’s failure to atone is a major cause of lingering tensions in East Asia.1 In Western Europe, by contrast, Germany’s willingness to atone for its World War II aggression and war crimes is said to have promoted European rapprochement. But is this interpretation correct, and more broadly, what is the relationship between apologies and international reconciliation? A close examination of Japan’s and Germany’s postwar international relations suggests that observers are correct that denying or glorifying past violence inhibits international reconciliation. But it turns out that apologies are a risky tool for peacemaking: they can do more harm than good.

Why might apologies matter in international politics—that is, why are they not merely dismissed as “cheap talk”? Apologies—or more broadly, national remembrance—matter because the way countries represent their pasts conveys information about foreign policy intentions. As countries remember, they define their heroes and villains, delineate the lines of acceptable foreign policy, and send signals about their future behavior.

National remembrance can be observed in both official policies and in debates within wider society. Official remembrance would include leaders’ statements about the past (e.g. apologies). Governments might offer reparations to former victims, and may hold perpetrators of past violence accountable in legal trials. Governments educate their societies about the past through their education systems (i.e., textbooks) and through commemoration: monuments, museums, ceremonies, and holidays.2 Through these policies, national governments can strongly influence—but cannot fully control—the way the wider society remembers the past. Thus other important indicators of national remembrance are societal ones: such as the statements and activities of mainstream opinion leaders (e.g. members of the political opposition, the press, and public intellectuals).

National remembrance might be more or less apologetic. Social psychologists have identified core components of apologies that transcend cultural differences: at a minimum, an apology requires admitting past misdeeds, and expressing regret for them.3 Thus, “apologetic remembrance” is that which conveys both admission and remorse. At the other extreme, “unapologetic remembrance” either fails to admit past violence, or fails to express remorse for it. Unapologetic remembrance comes in many varieties; a country may justify, deny, glorify—or simply forget—past violence.

A country’s remembrance should send the strongest positive signal about its intentions when it engages in a broad range of official apologetic policies—statements, reparations, trials, commemoration, and education—and when wider society endorses these policies. Remembrance should be less reassuring if government policy is apologetic, but wider society exhibits denials and glorifications. At the negative extreme, a country’s intentions should appear hostile if it pursues a broad range of policies that deny or glorify past violence—and if society endorses such policies.

I test this theory about the link between remembrance and intentions in the cases of Japanese and German foreign relations after World War II. Below I summarize three major findings.

Pernicious Denials

The Japanese and German cases provide strong support for the view that unapologetic remembrance (denials, glorifications, or justifications of past violence) fuels distrust and elevates fear among former adversaries. In Japan, frequent denials by influential leaders and omissions from Japan’s history textbooks have repeatedly poisoned relations with South Korea, China, and Australia. Throughout the postwar era, South Koreans expressed cautious optimism when a Japanese Prime Minister apologized for Japan’s colonial record in Korea. But as Japanese contrition triggered backlash—in which prominent politicians and intellectuals justified or denied Japan’s past atrocities—South Koreans concluded that Japanese contrition was insincere and that Tokyo continued to harbor hostile intentions. As expressed by South Korean president Kim Dae-jung in 2001: “How can we make good friends with people who try to forget and ignore the many pains they inflicted on us? How can we deal with them in the future with any degree of trust?”4 Chinese and Australian observers also monitored Japanese remembrance in the postwar years, expressed anger and dismay at Japanese denials, and linked their distrust of Japan to its failure to admit its past atrocities.

In Europe, West German acknowledgment of the nation’s wartime aggression and atrocities facilitated reconciliation between West Germany and the Allies. During the occupation, the Allies encouraged German admission of its atrocities (particularly within education policy). This was seen as critical to preventing the return of German hyper-nationalism, and to the creation of a peace-loving West German state. Later, France and Britain continued to monitor West Germany’s remembrance: they praised its willingness to explore its past, and they expressed anxiety about any perceived signs of revisionism. Both the Japanese and German cases thus suggest that avoidance of denials and glorification of past violence is a key step in international reconciliation.

Necessary Apologies?

Although denials and glorifications appear very harmful to international reconciliation, it is clear that many bitter enemies—including Germany and France—have reconciled with very little atonement. Early after the war, Bonn expressed modest contrition. Although it offered a lukewarm apology and paid reparations to Israel, West German commemoration, education, and public discourse ignored the atrocities Germany had committed, and instead emphasized German suffering during and after the war. Nevertheless, during this era of minimal contrition West Germany and France transformed their relations. By the early 1960s, both French elites and the general public saw West Germany as their closest friend and security partner. Bonn’s remarkable expressions of atonement—wrenching apologies, candid history textbooks, memorials to Germany’s victims and the largest reparations to victims—had not yet occurred.

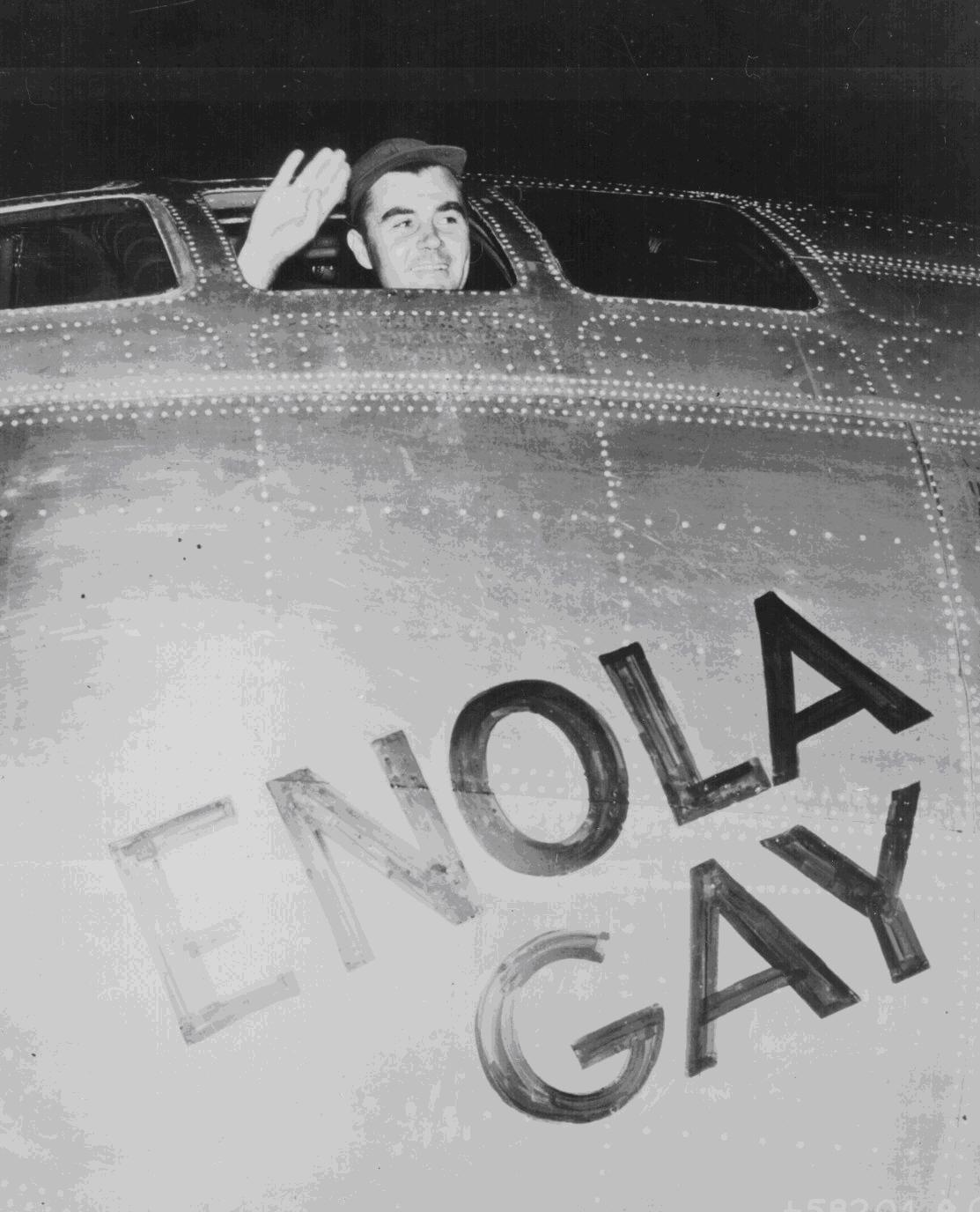

Other World War II enemies reconciled with even less remorse. Both the British and Americans established close and even friendly relations with West Germany without apologizing for fire bombing German cities, a campaign that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians. Japan and the United States built a warm relationship and solid security alliance in spite of the fact that neither government has apologized for its wartime atrocities. Furthermore, the European partners of Italy and Austria ignored the blatant dodging of culpability in these former Axis countries. Although denying or celebrating past atrocities will inhibit the reestablishment of good relations, countries frequently reconcile with very little contrition in the form of apologies and reparations.

Beware the Backlash

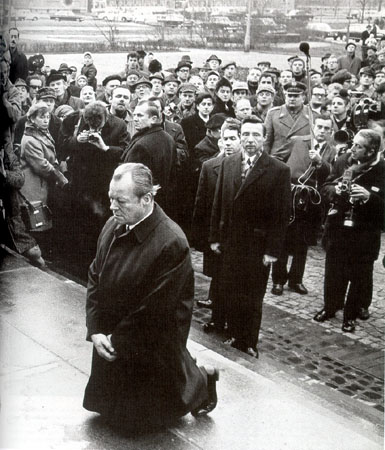

In 1970 West German Chancellor Willy Brandt fell to his knees at the Warsaw Ghetto, and recently South Korean President Lee Myung-bak has urged the Japanese emperor to follow suit by apologizing to the Korean ‘comfort women’. Although many analysts argue that Japan and other countries should adopt the German model of atonement, such recommendations neglect to consider the risks of such policies. As evident in Japan and elsewhere, official expressions of contrition often prompt a backlash. Conservatives in particular are likely to offer a competing narrative that celebrates—rather than condemns—the country’s past and justifies or even denies its atrocities. Thus contrition can be counterproductive: foreign observers will be angered and alarmed by what the backlash suggests about the country’s intentions. The great irony is that well-meaning efforts to soothe relations between former enemies can actually inflame them.

Comparison of the Japanese and German cases thus raises a puzzle. Japan’s modest efforts to offer contrition repeatedly triggered sharp outcry among conservatives, who justified and even denied past atrocities. Because of backlash, Japanese contrition ended up alarming Japan’s neighbors. In Germany, by contrast, far more ambitious efforts at contrition did not provoke a similar backlash. Though some West German conservatives preferred to emphasize a more positive national history, they did not deny or glorify Nazi crimes. The French thus viewed West German debates about the past as healthy, cathartic experiences for the country’s democratic development—and as a reassuring signal about its intentions.

Whether or not contrition is likely to heal or hurt thus seems to depend on the occurrence of backlash. Though more research is needed about the conditions under which backlash will occur, there are powerful reasons to believe that contrition will be very controversial. First, the absence of backlash in the West German case can be explained by its unusual strategic circumstances after the war. During the Cold War, West German conservatives—those most likely to oppose contrition—had powerful reasons to keep quiet. Their key foreign policy goals –German reunification and protection from the Soviet Union—all required reassuring NATO, which required a clear denunciation of the Nazi past. West Germany thus faced constraints that are unlikely to be so severe elsewhere.

Indeed, evidence from around the world shows that backlash to contrition is a common occurrence. In Austria, Jörg Haider’s vocal criticism of apologies and stalwart defense of the wartime generation resonated with voters, who catapulted him and his party from the fringe into national leadership. Conservatives in France, Switzerland, Italy, and Belgium mobilized against attempts to confront their World War II collaboration. In Britain, proposed apologies for British policies in Ireland, and for complicity in the slave trade, both sparked outcry. In the United States, a proposed Smithsonian exhibit that discussed the horrors of Hiroshima and questioned the necessity of the bombing triggered immense protest, including statements of justification from Congress, veterans’ groups, and the media.

The frequency of backlash is predictable from the standpoint of domestic politics. Many conservatives are ideologically opposed to contrition, seeing it as anti-patriotic. Opportunistic politicians will also notice that many of their constituents strenuously object to contrition: it impugns wartime leaders, veterans, and the war dead. To be sure, the German case shows that backlash to contrition is not inevitable, and scholars should investigate the conditions under which it is more or less likely. However, all of these reasons suggest that backlash will be common.

Resolving the Dilemma

If denying and glorifying the past fuels distrust and fear, yet apologies risk triggering counterproductive backlash, how should peacemakers deal with the legacy of the past? One strategy, used successfully by West Germany and France, is to construct a shared and non-accusatory narrative between nations. Rather than frame the past as one actor’s brutalization of another, leaders can structure commemoration to cast events––as much as possible––as shared catastrophes. Countries can remember past suffering as specific examples of the tragic phenomena that afflict all countries, such as war, militarism, or aggression. For example, rather than lament German brutality, the settings and tone of Franco-German commemoration at Reims cathedral (1962) and Verdun cemetery (1984) highlighted the suffering that militarism and European anarchy had brought to both peoples, thus underscoring the need for European unity.

Another strategy is multilateral. East Asian leaders and activists who want to raise awareness about the World War II “comfort women,” for example, might organize a multinational inquiry about violence against women in wartime: widening the focus beyond Japan’s crimes to consider similar atrocities committed by many countries in many wars. Multilateral textbook commissions––used extensively in Europe and also recently in East Asia–– are another promising approach. Because such multilateral settings do not wag a finger at one country uniquely, conservatives are less likely to mobilize against them.

These approaches do have significant drawbacks. If justice is the policy goal, such approaches may be flawed. They downplay the heinous acts that occurred and divert attention from the people and governments who committed them. But, as John Kenneth Galbraith famously commented, “Politics is the art of choosing between the disastrous and the unpalatable.” These strategies are unpalatable in many ways––yet are wise from the standpoint of international reconciliation.

Recommended citation: Jennifer Lind, “Memory, Apology, and International Reconciliation,” Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 47-7-08, November 21, 2008

Recent Japan Focus articles on issues of war memory and reconciliation include:

Takahashi Tetsuro, Kaneko Kotaro and Inokuma Tokuro, Fighting for Peace After War: Japanese War Veterans recall the war and their peace activism after repatriation

Wada Haruki, Maritime Asia and the Future of a Northeast Asia Community

Oe Kenzaburo, Misreading, Espionage and “Beautiful Martyrdom”: On Hearing the Okinawa ‘Mass Suicides’ Suit Court Verdict UPDATE

Matthew Penney, War and Japan: The Non-Fiction Manga of Mizuki Shigeru

Mark Selden, Japan, the United States and Yasukuni Nationalism: War, Historical Memory and the Future of the Asia Pacific

Hong KAL, Commemoration and the Construction of Nationalism: War Memorial Museums in Korea and Japan

Notes

- Economist, May 13, 2006; Thomas J. Christensen, “China, the U.S.-Japan Alliance, and the Security Dilemma in East Asia,” International Security Vol. 23, No. 4 (Spring 1999), 49-80; Nicholas D. Kristof, “The Problem of Memory,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 77, no. 6 (November/December 1998); Thomas U. Berger, “The Construction of Antagonism: the History Problem in Japan’s Foreign Relations,” in G. John Ikenberry and Takashi Inoguchi, eds., Reinventing the Alliance: US-Japan Security Partnership in an Era of Change (New York: Palgrave. 2003), 63-90.

- On education see Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983), 26-35; Boyd Shafer, Faces of Nationalism: New Realities and Old Myths (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1972), 198. On commemoration see John Bodnar, “Public Memory in an American City,” in John R. Gillis, ed., Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1994), 74-89.

- Aaron Lazare, “Go Ahead, Say You’re Sorry,” Psychology Today Vol. 28, No. 1 (1995), 40; Michael E. McCullough, Everett Worthington, and Kenneth C. Rachal, “Interpersonal Forgiving in Close Relationships,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol. 73 (1997); Nicholas Tavuchis, Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1991).

- “ROK President Addresses Liberation Day Ceremony,” SeoulKorea.net, in Foreign Broadcast Information Service, South Korea, August 15, 2001.