Since 1990 both Japan and Korea have experienced “commemoration booms,” in which the number of private and public memorial museums and monuments has tripled.[1] These institutions provide narratives of each nation’s recent past and articulate the ideals of “nation” and “citizenship.” They recompose tales of a nation in order to make them relevant for public and private life. Like writing history, the museum collects and assembles fragments of the past and carefully re-contextualizes them into a narrative of the present. Precisely because of its role in institutionalizing social norms and values, the museum plays a crucial role in the production of national identity. It shapes the manner in which the nation creates its history, imagines its boundaries, and constitutes its citizenship.

Central to the “autobiography” of the nation is the representation of wars and death, memories of which are considered essential in guaranteeing the immortality of the nation. Benedict Anderson has written that:

Nations, however, have no clearly identifiable births, and their deaths, if they ever happen, are never natural. Because there is no originator, the nation’s biography cannot be written evangelically, ‘down time,’ through a long procreative chain of begettings. The only alternative is to fashion it ‘up time’ towards Peking Man, Java Man, King Arthur, wherever the lamp of archeology casts its fitful gleam.[2]

Since the nation has no fixed birth certificate, its biography can be written “up time” from its “originally present” toward its unlimited ancient past. The ancestral construction of the nation, according to Anderson, is marked by the narrative of death in reversed genealogy: “World War II begets World War I; out of Sedan comes Austerlitz; the ancestor of the Warsaw Uprising is the state of Israel.”[3] The war memorial museum creates a precedent for securing such an inverted genealogical construction of the nation’s ancient past. It supplies a formal structure for the nation to fashion itself toward its forefathers who died to guarantee the continuity as well as the immortality of the nation.[4] It also poses difficult questions. Can the forefathers be wrong when their wrongdoings secured “the goodness of the nation”? Can our heroes be killers? How should the enemy dead be represented? Can national war history be relational and plural when it is supposed to affirm the singularity of the nation?

In Asia, the transformations of post–Cold War geopolitics have opened new possibilities for inter-Asian relations and inevitably led to a rigorous interrogation of the region’s recent past. In the question of how to represent colonialism and catastrophic wars, war memorial museums based on the narrative of self-sacrificial death on behalf of a grateful nation have become among the most controversial sites. Especially as the battles over the history within and between Korea and Japan have become more intense and divisive, war memorial museums demonstrate the tension between official and societal memories of the past, revealing conflicting yet mutually constitutive assumptions of postcolonial Korea, divided Korea, and postwar Japan. While sharing much in common with other war museums, those in Korea and Japan led a life of their own according to particular temporal and geographical conditions.

I consider two war memorial museums: the War Memorial of Korea (hereafter WMK) and the Yushukan, a Japanese war memorial museum attached to the Yasukuni shrine, formerly a national sanctuary that enshrined the military dead as divine deities. Located in the center of each nation’s capital, both play symbolic and socially significant roles in the construction of nationalism. In Korea, the WMK was built “to commemorate martyrs and their service to the nation” and thus to prepare citizens “to face a future national crisis.”[5] In Japan, located in the shrine complex where conflicting memories meet, the Yushukan aims to nurture a sense of “lost” pride in being Japanese with a “glorious” history of war, posing a serious political question of how to come to terms with Japan’s recent past, colonialism, and wars. This essay examines how they write biographies of the nation with particular historical meaning. It focuses on the important role of the war dead in the creation of national immortality, and demonstrates that the source of this national ethos derives from the enactment of ethnic nationalisms in the two countries. I argue that the biographies of the nation written “up time” toward its ethnic “origins” are an attempt not only to create a linkage to the past, but also to produce an image of the future of the nation for today’s generation, who are experiencing forces of globalization. In doing so, this essay pays particular attention to the spatial and exhibitionary techniques to show how the museum stages carefully developed scenarios of the nation’s war histories and how it claims the heritage of patriotism and equates that tradition with the nation.[6]

My main concern here is ethnocentric nationalism in the two countries as staged in the war museums. Clearly they are embedded in different forms of nationalism, for Korea and Japan have mutually antagonistic historical trajectories—one the colonized and the other the colonizer. The conflicting experience of colonialism has harnessed them with different burdens over how to deal with histories. Even within national boundaries of each country, a discourse of the nation and nationalism has evolved in various ways in changing geopolitical and international contexts. In particular, Japan has experienced a shift in the dominant discourse of “Japan,” from the multi-ethnic empire to the mono-ethnic nation. [7] However, as Harumi Befu has elaborated, what has remained intact is a sense of Japanese ethnic homogeneity, uniqueness and superiority, enunciated as “nihonjinron.”[8] Also, while the WMK is a state-sponsored public museum, since the American occupation, the Yushukan has been an ostensibly private institution. However, given that the Yushukan attachment to the prewar State Shinto shrine, which is still strongly associated with the linked images of emperor, state, and nation,[9] the two museums are comparable in their political significance. Both demonstrate a growing obsession with ethnocentric nationalism. My contention is that the question of reconciliation with historical injustice cannot be seriously dealt with without problematizing ethnocentric nationalism, which is defensive, exclusive, and thus constraining. The self-reflection of nationalism is indeed at the core of the issue of reconciliation within as well as between nations.

I. The War Memorial of Korea (WMK)

The WMK, conceived in 1988 under the Roh Tae Woo government, was opened at the site of the former Korean Army Headquarters in downtown Seoul in 1994.[10] Despite public discomfort over its military appearance, the WMK survived the demise of the military dictatorship and was embraced by the civilian regime headed by President Kim Young Sam as a reminder to Koreans of the ongoing threat posed by North Korea.[11]

Like other war memorial museums, the WMK commemorates the war dead who sacrificed their lives for the defense of the nation and imbues the younger generations who have no memory of war with patriotic spirit. It provides historical grounds for safeguarding the country with “awareness of national security.”[12] However, there is something particular about the museum. It not only constructs a narrative of patriotism but also, more problematically, an “ethnic” lineage of the nation, a sacrifice of forefathers for the children of the nation: the Koreans. By doing so, it seeks to form a national subject based on the idea of Korean ethnic nation as originated from ancient times. The discourse of ethnic nationalism posits the state, nation, and ethnicity as identical categories. Ethnic nationalism has been a key organizing principle in Korea, yet its historicity, eternity, and naturalness have not been seriously questioned.[13] In the following, I explore a narrative construction of ethnic nationalism by analyzing the architectural and visual mechanisms of the museum. I focus on the ways in which the museum constructs the Korean ethnic nation in terms of war, kinship, and familial sacrifice and how this process of making “we” is closely related to the construction of “others,” namely North Korea, Vietnam, and Japan.

The spatial order of the memorial hall: national ritual in the ancestral temple

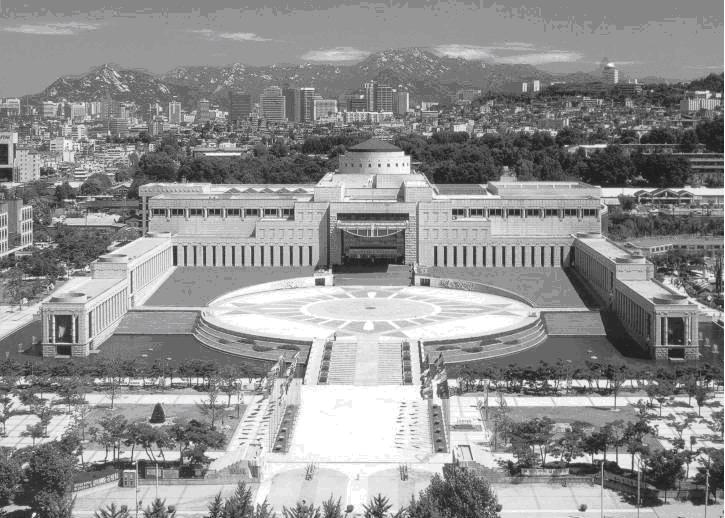

The WMK is designed like a temple secluded from the secular world outside. It nevertheless overpowers its surroundings with its perfect symmetry in classical Greco-Romanic style (Figure 1).[14]

Despite this Western façade, however, I would argue that the organizing principle of the museum space is that of a Confucian temple. The WMK memorial site is organized in the spatial sequence of the pathway, the steps, the moat, and the plaza. The spatial sequence of WMK creates a formal temporal sequence for visitors to follow. [15]

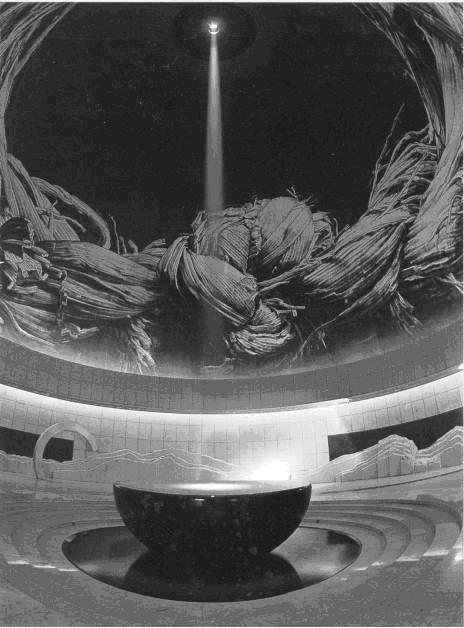

Upon entering the main gate, people embark on a ritual passage programmed by the museum. The spatial and temporal sequence heightens a sense of solemnity. Passing the pathway, the steps, the moat, and the plaza, all organized along the North-South axis, visitors are drawn to the museum building. They continue the procession by ascending to the Central Hall, a round room with a skylight in its domed ceiling. The Central Hall opens onto a long corridor lined on both sides with half-body statues of heroic warriors. This corridor ends at the hemispherical domed Memorial Hall, the innermost “shrine,” located at the north end of the museum (Figure 2).

Concealed behind the layers of space along the axial line, the Memorial Hall recalls the ancestral inner shrine. At the apex of the dome, a blue beam is projected straight down onto a bowl. With the concentrated light from the sky, the bowl resembles an ancestral altar where visitors can contemplate and perhaps communicate with the war dead. The bowl and the light are the focal point where the spirit of the war dead meets with the living.

The movement from the exterior to the interior is thus a journey back to the “origin.” The trip from the present to the past is a search for a linkage with tradition to legitimize the current regime. Yet there is more to it than that. The logic of reversed genealogy is designed in the Confucian order of time, space, and origin. It is in the scenario that the patriotic present pays tribute to its ancestral past where it was born and to where it should return. The journey to the innermost shrine is not only for the living, but also for the dead. Like the living, the spirit of the dead returns to, and becomes part of, the family of ancestors from whom they came. Both the dead and living find themselves returning to the ancestor from whence they came and where their sacrificial life for the nation is legitimized.

The WMK seeks to produce a national subject based on ethnicity by encouraging people to recognize their shared origin and not to forget those to whom they owe their being. The museum suggests that as long as visitors identify with the dead, they will recognize their sacrifice, as well as their blood relationship, and therefore be united in a national community. In following the order of the exhibition, people pay tribute to the dead and reaffirm the shared ancestral heritage to which “we” all belong. Like an ancestral temple, the museum represents the origins of a lineage by reminding people of the historical existence of their ancestor and their duty to keep such a memory alive.

The war history room: constructing the living war dead

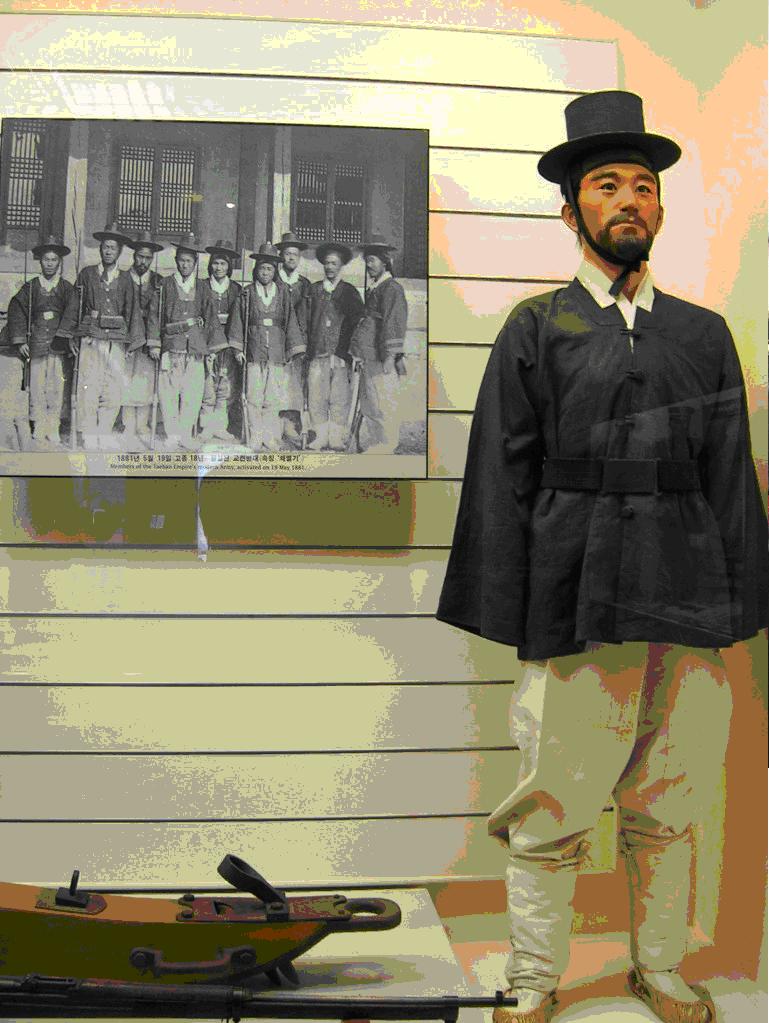

The museum tells of the linkage of the national dead and the national living. The dead and the living mirror each other to ensure the continuity of the nation within which ethnic Koreans are embedded. The exhibition sequence from exterior to interior and from secular to sacred is programmed to awaken the national dead to interpolate the living, demanding the cooperation of all the war dead to perform as the ancestors of the living. As an apparatus for the production of ethnic nationalism, the museum claims to speak for “Korean” war dead who did not know themselves to be such. By bringing together wars from the Great Victory at Salsu (612) to the Korean War (1950-53), the museum provides coherence for a larger historical context of a lineage of patriotic Korean ancestors. Speaking on behalf of the ancestors, the museum also speaks subtly to visitors about who they are in relation to the war heroes. The War History Room, for instance, narrates a history of Korea from the prehistoric age to the present. It stages weapons technology and military tactics of each period in a standardized format which enables visitors to see them as similar to each other and therefore sharing the same heritage. The display of military uniforms also operates by such a parallel logic. A window display presents a line of mannequins in variously styled military uniforms of the Taehan Empire (1897–1910). Yet the facial expressions of the mannequins are identical. There seems no need for the museum to explain who the military men were, not only because they all look alike but also they all look like “us,” Koreans, who are capable of changing costume. This group is immediately linked to another group from the Choson Dynasty, which is again linked to others from ancient times (Figures 3 & 4).

The question is not how different but how similar they are to each other. Who else would fit into this series of armor and helmets except “we” ethnic Koreans? They are standing there to represent a continuing military tradition across time, emblematic of an identical and collective Korean heritage.

The museum impresses people with the vast numbers of the war dead. A series of memorial panels in polished black marble inscribed with the names of Korean soldiers and policemen killed in the Korean War and the Vietnam War is located in the left and the right gallery wings which extend from the main exhibition building. The 170,585 names of the dead are ordered according to the year they fell and the military units. Their names appear in a standardized format and the rows of panels remind one of their mass sacrifice rather than their individuality. The 200 meter long gallery appears more like the space for the tomb of the unknown soldiers. Anyone can be there for the same reason. There seems no need to personalize any of them. Their presence and death for the survival of the nation are all that matter (Figures 5 & 6).

One could say that personal memories are not encouraged in the Confucian temple built for collective identification. Visitors can only see the names as interchangeable with one another and assembled as the collective body of national heroes. In the attempt to nationalize the war dead, no other identities are allowed except that of ethnic Korean. It in this ethnicity that official nationalism lives. The museum probably modeled its exhibition technique on that of the National Memorial Cemetery (Kungnip hyo’nch’ung won) which was built in 1956 as a military burial ground shielded by auspicious mountains and the Han River.[16] As a site of national mourning, it enshrines remains of soldiers and patriots as national heroes, physically and symbolically. In it, the individual death becomes standardized and identical under the collective category of the Korean nation.[17] By rescuing the dead from obscurity and giving them a national meaning, the museum creates not only political legitimacy but also the “ethnic” lineage of the state. Once the war dead are enshrined as Korean heroes for all to see, the state claims its legitimacy as the rightful bearer of a Korean ethnic nation.

Just as the museum represents the war dead as equivalent Koreans, regardless of their glorious or shameful deeds, and regardless of rank, it also seeks to embrace visitors as collective Koreans. When the spirit of the dead conjures up a Korean ethnic collectivity, the past dead and the present living become one and indivisible. The exhibition also prepares the ground for the future war dead. Today’s young pilgrims to the memorial are placed in the position of future fellows of the dead. It is perhaps more than a coincidence that the museum provides an auxiliary facility for wedding ceremonies. This brings together the idea of normal family, unconditional loyalty, and the future reproduction of the “pure” national subject, as if ethnic purity itself guarantees the future of the nation. Who will guarantee the existence of the ethnic nation? The museum perhaps answers that it is the children. Moreover, it is for those yet-to-be-born “Koreans” that we work hard, sacrifice, and, if necessary, sacrifice our lives. Crucial to the unborn is the implied meaning: the innocent unborn descendants will honor us for giving life to them. The museum looks forward by constructing the idea of national (ethnic) “purity” against the fears of national degeneration. The sanitized space shows the museum’s obsession with “cleanliness” as a basis for “national health” and “national youth.” The task of the museum is thus to ensure the non-decay of the nation and to celebrate national virility.

Representing the invading others: The U.S. and North Korea in the Korean War

Consistent with the discourse of ethnic nationalism, the WMK degrades North Korean communism as anti-nation (ban minjok) which needs to return to the “normal” state (South Korea) to recover true Korean nationhood. The major focus in the exhibitions of the Korean War, seen as one of the most critical threats to the nation, is less the Cold War competition between hegemonic powers and more the confrontation between the two Koreas over the question of who is the rightful heir of Korea.[18] The Korean War Room, the largest exhibition section, presents the dominant narrative of the victimization of “innocent” South Koreans by the invasion of “tainted” North Korean communist aggressors backed by China. Two strategies of representation can be discerned here. First is the display of victimhood, and second the determinacy of South Koreans (especially civilians and students) to resist. Interwoven into this progression is the involvement of U.S. and U.N. forces in fighting for the “free world” against the Communist forces of North Korea and China. The first exhibition section of the Korean War indicates clearly that the war was started by North Korea. Civilians are shown suffering from the brutal acts committed by North Korean soldiers. The museum carefully explains the involvement of the U.S. as helping defend the territory of South Korea, emphasizing that the U.S. got involved only after the collapse of the crucial South Korean defense line at the Han River. The key message is that the U.S. (and later U.N. international forces) joined in only after South Korea had long sought to defend against invading North Korean forces.

The Korean War, however disastrous, is recast to highlight the resilience, idealism, and fulfillment of the Korean nation under the leadership of the South Korean state. In this narrative, the participation of U.N. forces on the side of South Korea is portrayed as an expression of international solidarity to defend the “free democratic world”, which includes South Korea. Several panels, some with documentary videos, depict scenes of battles, weapons and wounds showing South Korean and U.S. soldiers working hand in hand to push back the North Korean invaders. The U.S. is presented through images of Douglas MacArthur, rifles, aircraft and medical support, all to help South Koreans to defend, to launch a counter offensive and even to move north to capture the North Korean capital, Pyongyang. The museum depicts the success of this cooperation as an indication of the capacity of South Korea to work together with nations of the “free world” to fight communism. The U.S. supporting role in the War is best illustrated in the dioramic scene of “Medical Activities by the Field Hospital.” Along with the panel description that “the medical support capability of the ROK armed forces were extremely insufficient. But through medical support from UN forces, the wounded were treated in timely ways,” the diorama scene displays the U.S. presence through the aid boxes at the entrance to the hospital (Figure 7). The message is clear. The U.S. came here to aid, but South Koreans were the major actors at the scene.

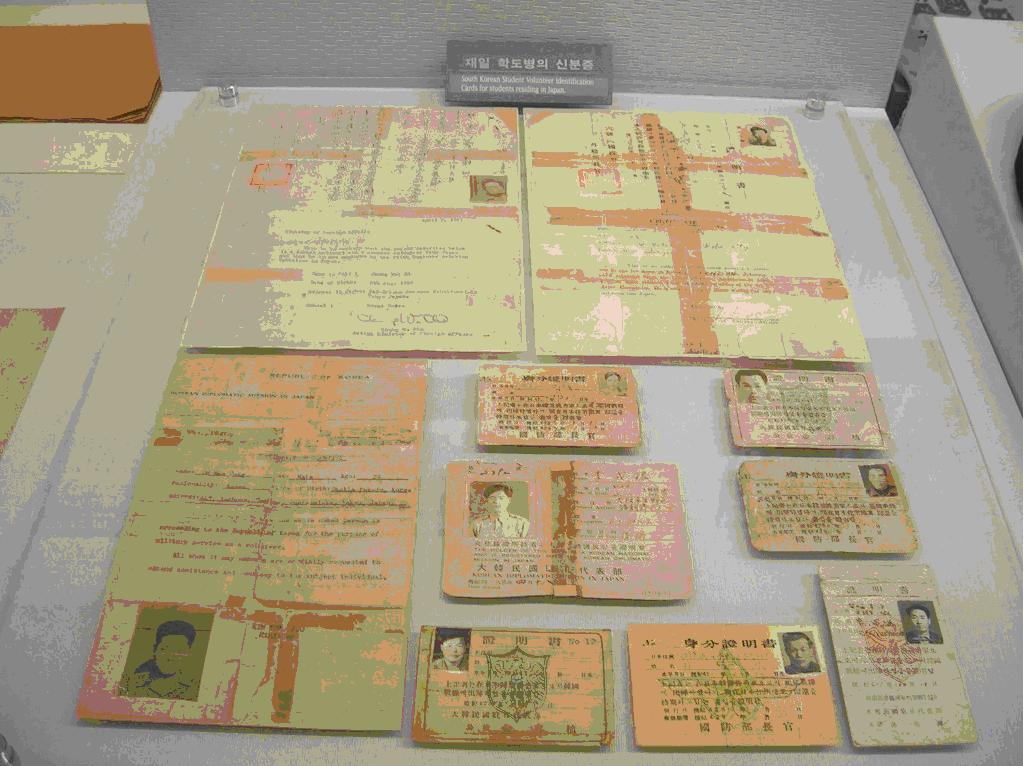

The U.S. is a major supporter of South Korea, but the survival of the nation relies on the resilience of the nation itself. Nothing more clearly demonstrates this than the depictions of the involvement of South Korean student volunteers and the Civilian Commando Units in fighting against the North Korean invasion. The displays of civilian voluntary forces seem more powerful than the war machines mobilized by foreign supporters. Right next to the panel on U.S. and U.N forces, the museum shows students fighting with bloody spears, their fallen bodies displaying university hats, school buttons and of course the Korean flag stained with signatures from students and traces of their struggles. The body, soil and blood represent most affectively the patriotic South Korean civilians who willingly and spontaneously formed their commando groups “to defend their country.” This patriotic spirit extends to Korean students overseas. Korean students in Japan are displayed alongside their counterparts in Korea in their fight against the North Korean invaders (Figures 8 and 9). With those (even foreign troops) who sacrificed themselves to defend the nation, visitors to the museum are asked to remember the goodness of the Korean nation. The nation is presented through the death and sacrifice of its “innocent” volunteering youths and embraces the free world.

While trying to minimize the historic dependency of South Korea on US forces, the museum finds ways to acknowledge the role of the U.S. In remembering the patriotic sacrifice of the children of the nation, it does not forget the American and transnational soldiers mobilized by the U.S. and the U.N. to fight on behalf of South Korea. One section of the memorial panels in the gallery wings is dedicated to these international soldiers who were ordered according to their nations and units. The U.S. with the largest number of war dead (33,642 out of a total of 37,645) occupies center stage. Unlike Korean soldiers who do not need to be introduced since they are all from “Korea,” American soldiers demand identification of where they were from. The fallen American soldiers are identified by their home states. Above the memorial panels dedicated to the U.S. and the U.N. soldiers killed in the Korean War, an inscription says “Our nation honors her sons and daughters who answered the call to defend a country they never knew and a people they never met,” a quotation from The Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. In some ways, the willingness of the children of “all” nations to die for South Korea in the fight against Communism seems to convey on South Korea a legitimacy to exist as a nation of the “free world.”

The Vietnam War and the recovery of the national self

The emphasis on the agency of the South Korean nation continues in the battle ground of Vietnam. In many ways, the section on Korean participation in the Vietnam War represents the psyche of the nation in overcoming the history of the Korean War. It shows not only Korean leadership in fighting against communism, but also in bringing Vietnam to the “civilized” world of freedom– something that South Korea would wish to do for North Korea in future. In this sense, the panels on the Vietnam War tell us much about the psychic recovery and the post-Korean War syndrome of South Korea, which was expressed in Vietnam with a vengeance. The sending of Korean troops to Vietnam (between 1965 and 1973) is thus represented as an act of a member of “freedom crusaders for world peace” and a chance to gain “confidence and experience in building a more self-reliant defense force” as well as a righteous mission to bring Vietnamese the democracy, freedom and peace that only become possible in the anti-communist state.[19] In addition to military operations, it highlights the Korean army’s engagement in the reconstruction of Vietnamese civilian facilities. For example, the museum displays at the center of the exhibition room Korean soldiers building a school, helping them mechanize rice production and constructing a new bridge in concrete (Figure 10).

Both North Korea and Vietnam are represented as objects of the patronizing mission of guiding communists to the “free world.” Yet there is a fundamental difference in the museum’s portrayal of Vietnamese and North Koreans. While the communist Vietnamese are portrayed as inhumane and barbaric perpetrators, the North Koreans are presented as dangerous communists yet “brothers” who have gone astray and pitifully left the family by adopting “foreign” communism. On this front it is instructive to examine the museum’s portrayal of a North Korean. Outside the museum there is The Statue of Brothers, a monument which depicts two solders in different military uniforms holding each other on a cracked hemispherical pedestal (Figure 11).

According to the catalogue, the two soldiers represent brothers who met on the battlefield as enemies, but finally reconcile with “brotherly love.”[20] The younger brother, here virtually a child, represents a North Korea soldier, politically communist yet ethnically Korean who, after losing everything in future will return to the embrace of the elder brother, the heir of the family’s house.[21] Here, a North Korean soldier is humanized as a “younger brother” who returns to the “elder brother,” who has preserved the unbroken heritage of the nation. The military heritage is then presented in the monument located at the other side, the replica of the memorial stele (erected in 414) dedicated to the military achievement of King Kwanggaeto the Great from the ancient Koguryo kingdom. These two monuments meet at the new structure, The Korean War Monument, which was built to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Korean War with ancient and contemporary symbols of prowess. Erected at the centre of the museum complex, the 32 meter high monument in the shape of a divided bronze sword flanked by two gigantic groups of patriotic Koreans (4 meters high) embodies the museum’s obsession with masculinity (Figure 12). As indicated by Sheila Miyoshi Jager, “the masculinist logic of the official commemorative culture” makes a connection between “the military, manliness and nationalism.”[22] The association of familial piety and national virility further suggests that the future reconciliation would be framed within the code of the patriarchal ethnic family.

Where has Japanese colonialism gone?

The representation of Japanese colonialism in the WMK reveals another aspect of the political culture of postcolonial Korea. Despite the fact that modern Korea was profoundly affected by the colonial experience, the WMK virtually ignores Japanese colonialism. As Jager observes, the embarrassing time of colonialism becomes “a mere blank period” in the Korean military history narrated in “the masculinist language of the national self-definition.”[23] It is understandable that the museum pays close attention to the ChosÇ’n dynasty, in contrast to the peripheral position of the colonial period, to prove Korean “manliness”. However, more is at stake than an enterprise to overcome a sense of being emasculated. The invisibility of the colonial past implies that Japanese occupation did not change the character of the Korean military tradition but merely proved Korean prowess.

By emphasizing heroism and resistance under colonialism, the museum projects the colonial past as a world absolutely divided into “we,” Koreans, and “they,” Japanese. “We” are related across generations in a homogeneous ethnic bond against “they.” Japan is counterpoised against Korea. These two antagonistic political forces confirm the ethnic coherence of the Korean nation, which was in fact constructed as a reaction to the Japanese colonial ideology that Japanese and Koreans share a common ancestor. The obsession with ethnic distinction as well as military strength indicates that the museum functions to redeem the humiliating experience of being colonized by staging a coherent story of the nation through images of family, ethnicity, patriotism, and masculinity. In this sense, the absence of the colonial period in fact actively constructs an ethnic lineage of the nation’s military patriotism. Japanese colonialism is a humiliating part of Korean history, one which remains difficult to integrate into the national imagination. Out of this selective forgetting and remembering of Japanese colonialism, a “patriotic” community of the Korean nation emerged. In creating a seamless familial history of the Korean ethnic nation, the museum dissociates postcolonial Korea from colonial Korea.

The WMK’s effort to construct the nation’s military patriotism based on the idea of a common bloodline and shared ancestry is closely associated with the making of Korean “others,” namely North Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. These others, while constitutive of Korean nation, are featured so as to highlight the continuity of Korea. In this sense the nation is not created out of historical rupture but rather it lives on the basis of continuity while “others” serve to highlight its continuing prowess. A good illustration of this is the two groups of wall sculptures depicted on the pedestal of the museum building. On the left is the Righteous Army formed at the end of the dynastic era and on the right is the Independence Army created during the colonial period to fight against Japanese occupation (Figures 13 and 14). The effort to make connections with military tradition is clear, but in the museum there is no mention of how Japanese colonial rule contributed to the formation of the South Korean Army. Assumed here is the sameness, that is, the essence of being “Korean.”

North Korea has a particular significance as the most threatening but ethnically related other. Therefore, this otherness has to be reconciled but at the same time maintained as a political ground on which the South Korean state proclaims its legitimacy or at least superiority in terms of anti-communism, a dominant state ideology throughout the second half of the twentieth-century. Anti-communist nationalism has lost its hegemonic position over the emerging discourse of peaceful unification as symbolized by the the summit meeting between the leaders of the two Koreas, Kim Jong Il and Kim Dae Jung, in 2000. The WMK nevertheless maintains a tone of anti-communism as an underlying narrative of postwar history. It seeks to construct legitimacy for the South Korean state by staging ethnic patriotic nationalism against “others” from inside as well as outside.

Through selective remembering, the WMK creates a seamless history of the nation’s military patriotism based on a common bloodline and shared ancestry. The process of making a national subject of Korea is closely associated with the making of Korean “others,” namely North Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. North Korea has a particular significance. It is simultaneously the most threatening and an ethnically related other. Therefore, this otherness has to be reconciled but at the same time maintained as a political ground on which the South Korean state proclaims its legitimacy or at least superiority in terms of anti-communism. The museum seeks to position Korean visitors as an ideal citizen with a shared memory of the war. It does so, however, by suppressing discordant memories of the war such as the massacre of non-combatant prisoners by South Korean authorities in Taejon in July 1950 and the killings of villagers by the U.S. soldiers at Nogunri. The violence of South Korean and U.S. authorities have not found a place to be remembered. Likewise, the brutality against Vietnamese civilians is nowhere hinted at in the museum.[24]

II. The Yushukan and Japanese Historical Memory

The most important Japanese museum representations of the Asia-Pacific War indeed of any modern war involving Japan during the immediate postwar decades were the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum. In emphasizing the horrors of nuclear war, and in presenting the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the victims of that war, the museums underlined a Japanese commitment to peace and elided the military past that had culminated in empire, war, and defeat for Japan and had brought great suffering and mass death to the people of China and other Asian nations. The peace museums thus produced a narrative of the Japanese nation as both the victim of war and a force for peace. The resultant “peace culture” made it possible for many Japanese to “forget” the history of Japanese imperialism and aggression in Asia.[25] This peace culture has been countered by the new refurbished war memorial museum, the Yushukan in Tokyo. Situated at Yasukuni Shrine, it urges visitors to “remember” Japan’s “glorious” imperial past, and celebrates the Japanese who sacrificed for emperor and nation in the Asia-Pacific War.

The Yushukan and Yasukuni Shrine

The history of the Yushukan tells of Japan’s modern history. It was first built in 1882 in order to honor soldiers who fell in combat at the time of the restoration that inaugurated the Meiji imperial state. It was expanded in 1908 to accommodate the increased collections after the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War and rebuilt in 1932 after the Great Kanto Earthquake. With Japan’s surrender in 1945, the museum was closed. Restored in 1986, it was reopened after renovation in 2002 with a new exhibition hall. Sharing much in common with war museums of other former imperial powers, the Yushukan is notable for its association with the symbolism of “emperor, war, nation and empire.”[26]

The Yasukuni shrine where the museum is located is notable for its close ties to the emperor and its links to modern Japanese warfare. Built in 1869 on the order of the emperor Meiji, it enshrines as deities over 2.4 million Japanese military dead from 1853 to 1945, the vast majority of whom died in the final year of the Pacific War.[27] It also includes Koreans and Taiwanese who fought and died with the imperial army as well as Okinawans, not just soldiers but also youths such as nurses and the male corps that were called up in the final days of the war. In return for sacrificing their lives for the emperor and the nation, the shrine rewarded them by elevating them as deities, hence objects of worship by the nation. In short, Yasukuni shrine glorifies self-sacrificial death while celebrating the imperial legacy. The authority of the shrine in fact depends on the practice of visiting, in which the living and the dead constitute a mirror image of the circle of decay and renewal, death and rebirth and bequeath and inheritance. One of the most special rites was attended by the emperor (in the person of his emissary) with offerings to the deities which in turn would bestow their blessings upon the emperor and the whole nation.[28] Although under the US occupation the shrine was formally separated from the state and made a private religious institution, the Showa emperor continued to visit, and his emissary participated in major rites each year. In addition, Prime Ministers, cabinet members and diet members regularly visited the shrine, in most cases in a private capacity. When Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro visited in his formal capacity in 1985, a storm of controversy led to an end of the practice until 2001, when Koizumi Junichiro made the first of five successive official visits. The visits both divided the Japanese polity and sparked criticism in China, Korea and other Asian nations, given the shrine’s association with the wartime ideology of emperor-centered nationalism.[29] Within this context, after several years of renovation, the Yushukan was reopened in 1985 and again, with new exhibits in 2002, its mission to renew a sense of pride in being Japanese by displaying the nation’s “glorious” war history.

Like Yasukuni, the Yushukan poses political questions that reverberate beyond Japan’s borders. The reopening of Yushukan is emblematic of the rise of Japanese neonationalism which celebrates the nation’s military past. In the 1990s neo nationalists launched a campaign to rewrite a “new history” that neither imposes “victim complex” on Japan nor assigns all blame for the catastrophic wars on the Japanese military state.[30] Strongly opposed to any apology or compensation for Japanese war atrocities, they claimed that affirmation of wartime Japan is the path toward full realization of Japanese identity, which was forcefully suppressed and abandoned under U.S. hegemony. The revival of the Yushukan is one important attempt to connect the present to the imperial past, a link that they believe has been undermined by the peace culture.

The Yushukan presents a version of the nation’s modern, which elevates the war dead as a symbol of sacred patriotism and celebrates its military past. In this sense the museum not only looks back at the imperial past as a proud tradition but also looks forward to reconstruct the nation on foundations of empire and war. In what follows, as in the WMK, I analyze the museum’s exhibition displays and spatial arrangements and examine how they rewrite nationhood.

Into the exhibition space: The spirit of the samurai

Yasukuni shrine is protected by a series of Torii gates that create a hierarchy of spatial transition from the world of mortal beings to the realm of the Shinto deities (kami). Passing the three gates built along the east-west axis, visitors proceed to the Inner Shrine where they can worship the war dead transformed into deities through a rite of apotheosis. Behind it is the Main Sanctuary, which is unapproachable by visitors and hidden from the view. The arbitrary denial of entry and the partial revelation of the shrine grant visitors a glimpse of the world beyond, while suggesting that the ultimate truth is reserved for those privileged to enter: the war dead and the priests who perform the rituals of apotheosis and propitiation. This deepest site is where the priests, accompanied by the imperial representative and others, make offerings to the deities and in return receive blessings from them for the nation. Located at the north side of the Main Sanctuary, the war museum seeks to incorporate the deification of the war dead into its exhibition space by conveying the aura of sacrificial death.

The renovated Yushukan features a new extension which has transparent glass walls and slightly tilted roofs (Figure 15). In stark contrast to the old Japanese imperial style of the main exhibition building, the new extension is modern and contemporary. As if to connect the past to the present, the new extension functions as an entrance lobby. It creates a brighter, modern, welcoming atmosphere where the individual and the national subject can be linked in “love of nation.”[31]

Upon entering the new lobby, a semi-open plaza with transparent glass walls, visitors first encounter the Zero fighter, the leading Japanese plane and one which frequently outclassed US fighters in the early phases of the war. Standing like a sublime object on the sanitized floor with no trace of blood and no hint of the disaster that confronted the Japanese air force, the immaculate object has been elevated into a sanctified object. The care that has been put into polishing the aircraft signifies the living who care for the dead. Cleanliness is indeed next to godliness. Once used by the war dead, the military artifact embodies their spirit. Preserved by the living, it becomes an inheritance that can be bequeathed to future generations to remind them of those who sacrificed their lives for them.

The Yushukan is organized to create circular movements starting from and returning to the Zero fighter in the hall (Figure 9). From the entrance lobby, visitors ascend from the entrance lobby to the exhibition halls, a passage that resembles the crossing of a bridge constructed to divide the realm of the living from the domain of the dead. This movement from the profane to the sacred also leads visitors to the past, from where the nation started. As the WMK traces back its military tradition, the Yushukan looks to the timeless “spirit of the samurai.”

In the middle of the dimly lit room named the Spirit of the Samurai, a vertical glass case enshrines a sword labeled “a marshal’s saber” with an explanation that “When the nation was in crisis, warriors were bestowed a sword from the emperor. Also in the modern battlefield, soldiers placed the sword on their waists. Since the age of the gods, the sword has reflected the spirit of Japan and the soul of the warrior. The sword is a symbol of justice and peace.” As the military weapon turns into a sacred object, war is given a noble and transcendent meaning. This single object represents “pure Japaneseness,” and in this purity “the spirit of Japan” is secured. This messages echoes from the scrolls hanging at the four corners of the hall. One of the scrolls writes, “We shall die in the sea, we shall die in the mountains. In whatever way, we shall die beside the emperor, never turning back.” Then, who is “we”? It continues, “The painful lives of those who cared for their country piled up and up, protecting the land of Yamato.” The story then goes back thousands years ago, “More than 2,600 years ago, an independent nation was formed on these islands… Japan’s warriors fought bravely, defending their homes, their villages, and the nation.”[32]

The museum asks visitors to value its antiquity as containing the spirit of the warrior which is the spirit of the nation. The museum is, it claims, precisely the place where people can witness and experience the timeless essence of heroism, loyalty and self-sacrifice for the nation. In this exhibition space, war death becomes an honorable and righteous act of obligation for a life of the nation inhabited by ethnic Japanese for thousands of years.

Liberating Asia

Like the WMK, the Yūshūkan displays an unbroken tradition of the sacrificial spirit of the nation that invokes Japanese military prowess. The Japanese war museum, however, long faced a dilemma: how to represent the aggressive and defeated war. This no longer seems a problem. The museum stages a seamless history of “glorious” warfare leading up to “the Greater East Asian War.” Before proceeding to the modern wars, it puts on display the rooftop of the (Ise) Shinto shrine decorated with forked finials and reminds visitors of the significance of the spirit of Shinto renewal in the foundation of the Japanese modern state. This link between the ancient Shinto shrine and the modern nation-state prepares visitors to understand that war is not a mere human tragedy but a sacred mission for the renewal of Japan and further to assure “the peace of Asia.” The museum presents Japan’s unavoidable yet heroic actions to achieve pan-Asian peace in the face of the encroachment of Western powers, including the Sino-Japanese War, the Russo-Japanese War, the invasion of China and the Asia Pacific War. In this narrative, the annexation of Korea is presented as liberation from China.[33] The story ends with celebration of the legacy of Japan for postwar independence movements in Southeast Asia: “When the war ended the people of Asia returned to their homes. Those whose desire for independence had been awakened were no longer the obedient servants of their [Western] colonizers… One after another the nations of Southeast Asia won their Independence and their successes inspired Africa and other areas as well.”[34]

The museum thus offers a history which affirms Japan’s military acts in Asia as a holy and defensive mission to protect the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” from Western imperialism. In doing so, it not only erases the atrocities committed by Japanese forces but also revives the imperial discourse of pan-Asianism.

Ethnic nationalism in the Yūshūkan

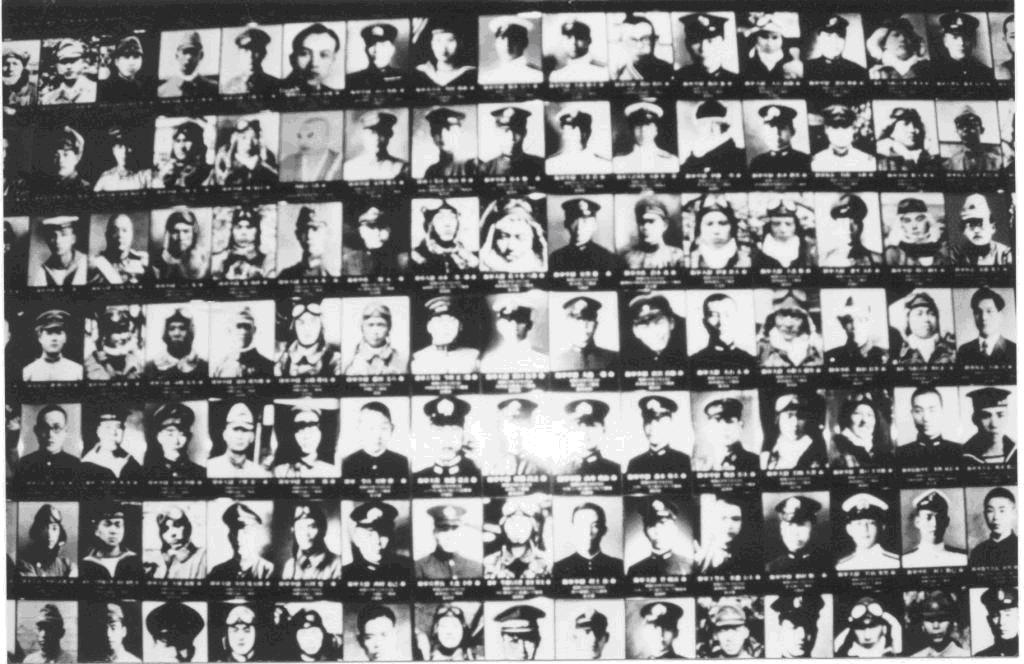

While invoking the wartime rhetoric of pan-Asianism, the Yūshūkan renew the concept of “Greater Japanese Empire.” In the exhibition section dedicated to “Mementos of war heroes enshrined at the Yasukuni shrine,” the wall is covered with individual photographs of those who died in the Asia Pacific War (Figures 16 & 17).

Each photograph, as small as the palm of a hand, shows the name and age of the individual dead. Yet, despite this personal identification, the soldiers remain nameless. They are all immersed in the vast canvas of collective death, a single body of the nation, stripped of all social and cultural significance. Yet this abstraction of individual death into a collective national whole brings up a compelling question regarding nation and ethnicity in Japan.

Tracing the genealogy of the discourse of the Japanese nation, Eiji Oguma has argued that the myth of Japan as a homogeneous and pure-blooded nation is largely a postwar construction.[35] With the collapse of the Japanese empire, for instance, the broadly accepted idea of the prewar period that Japanese and Koreans shared a common ancestor was transformed into the belief that Japanese and Koreans were fundamentally different in their culture and ethnicity.[36] In postwar Japan, Koreans and Taiwanese living in Japan, including veterans of the Japanese army, would be deprived of Japanese citizenship. Despite the instability of the concept of Japan, oscillating between the homogeneous nation and the mixed nation, however, as Harumi Befu has aptly pointed out, what has been maintained beneath the discursive shift of the nation in modern Japan is the idea of ethnic nationalism.[37]

Yasukuni shrine nevertheless enshrined some 50,000 ethnic Korean and Taiwanese soldiers who were mobilized to serve the Japanese empire and died in combat during the Asia Pacific War. Some bereaved families, who were informed only recently of enshrinement, demanded that the shrine return the souls to them. The shrine, however, rejected the demand saying that all had died for the emperor and nation and would be honored for their sacrifice. Like the shrine, the museum erases any reference to the multiethnic nature of those who died in Japanese uniform during the war. In the museum, these ethnic others, who were Japanese but not quite Japanese, are subsumed in a unitary Japanese identity that elides their ethnic identities.

III. A Crisis of Ethnic Nationalism in the Era of Globalization

The war memorial museums aim to convey an aura of sacrificial death that supposedly transcends individual physical annihilation. Yet the problem arises precisely in this practice of museumization of death. The attempt to present divine souls threatens the sacred aura as such. As Arjun Appadurai and Carol A. Breckenridge have argued, the museum is needed especially when “the separation of sacred objects (whether of art, history or religion) from the objects of everyday life has occurred.”[38] In the case of the Yushukan, the museumization of ritual suggests the decline of the shrine as a social practice and thus a need to remind people of its “sacred” meaning. Likewise, in the WMK, heroic death is presented as prime material for the foundation of national identity through objects in the form of exhibition displays, and monuments, extending even to souvenirs. The serialization of images can be seen as “a replica without aura” in Anderson’s term.[39] In this sense the two museums represent not the power but the loss of popular faith in military nationalism. In 1993, even before its opening, the WMK faced criticism of the lack of accountability of government spending for the museum and questioning the very need to build a war museum with such a belligerent appearance in the center of the city.[40] The museum in fact proved unpopular.[41] In particular, in the emerging new political relations with and public perceptions of North Korea, has faced continued pressure to accommodate the change. Perhaps partly as a response to such pressure, in 2002 the museum added a new monument, The Clock Tower of Peace, which portrays two young girls holding two watches, one stopped at the moment of separation of the two Koreas and the other moving toward future unification (Figure 18).

These new images of young girls and stopped watches remind us of the familiar icons of peace culture as presented in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki museums in Japan. Despite such a gesture to modify its militaristic and masculine image, the presence of the museum with a message of anticommunism and military patriotism continues to elicit criticism. In 2003, a group of citizens launched a campaign for an alternative peace museum, stating that “the WMK teaches our children how stronger weapons can kill more people… In this country with experiences of wars and state killings, we need a place to teach peace to our children.”[42] Some people resist the official representation of the museum by consuming it in ways different from its intended meanings. One popular website, for example, issued a call for “a new millennium techno party” to be held in the museum restroom:

A fun, weird party in the restroom at War Memorial Hall…The restroom of War Memorial Museum is the cleanest and largest in Seoul. This restroom will be totally changed to a wonderful party place. Some snacks, BBQ, cocktails and beer will be served…also, some funny events such as graffiti contest… and the performance by a five-man band Barberbershopporno led by the self-styled keeper of the women’s toilet.[43]

The restroom party fantasy illustrates how the museum can lead a life in popular consumption quite independent of the original official context. The celebration of nonsense, decadence, and obscenity is exactly what the museum tried to keep out of the public for the production of the “pure,” “healthy” and “normal” state of patriotic ethnic nationalism.

The Yushukan provoked similar reactions on the part of some.[44] Especially for those who painfully remember “stepping on dead bodies” and “there is nothing glorious about the war,”[45] the museum is deeply disturbing. A Japanese visitor regretted that, “the exhibits express neither condolences to victims of the U.S. air raids and atomic bombings nor remorse for Japan as an aggressor in Asia. I felt as if I had been exposed to the specter of Japanese militarism. … The museum souvenir shop sells T-shirts displaying the wartime slogan, “We Shall Win.”[46] In the project of securing the future embedded in the idea of nation with singular history, ethnicity, and identity, the museum continues to suppress the past violence, fear, and anguish experienced by both “Japanese Japanese” and other “non-Japanese Japanese.”

In a way all the different visual and spatial devices employed in the WMK and the Yushukan merge into what can broadly be termed ethno-conservative nationalism, which invents an ethnic-based tradition of military prowess. The obsession with military prowess is related to historical amnesia that both Korea and Japan have experienced. Both museums still find it difficult to integrate the dark past into their histories. The dark past is, therefore, kept in the family closet to avoid embarrassment. Or simply denied. Each only tells a story that the nation-family wants to hear about its ancestors and does not tell other stories, such as those of military aggressions at home and abroad, civilian participations in wrongdoings and collaboration with colonial rulers. “We” do not have to talk about the embarrassing deeds in “our family.” Out of the selective forgetting and remembering of the past, a seamless familial history of the ethnic nation and the idea of a patriotic and ever glorious national community have emerged.

The WMK performs an enactment of manliness in the discourse of ethnic nationalism, one which was suppressed under Japanese colonialism. It can be seen as an enterprise for overcoming a cultural crisis with respect to historical memories of colonialism, war, and the current phase of globalization. Hence, we see in the WMK a communal quest for a rooted identity expressed in the urge for ethnic unity, a role that can be most decisively played by the loud voice of military prowess. As in Japan, however, in a period which has witnessed a growing population of non-ethnic Koreans, it is a serious question whether a “democratized” and “globalized” Korea will further ethnicize or de-ethnicize the idea of nation and national membership. The issue of ethnicity and national membership becomes more complicated and even contradictory, as Katharine Moon aptly notes: “What is the meaning and content of the Korean nation if foreigners purport to claim Korea as their ‘second homeland’? Does Korea’s pursuit of democracy and globalization require that it alter its definition of nation?” [47] Furthermore, the changing relationship between women and the state also challenges the patriarchal definition of the Korean ethnic nation.

The Yushukan similarly calls for the recovery of Japanese military identity by affirming the wartime past at the center of national character and identity. Toward the end of the twentieth century, Japan confronts a divide between those who share the memory of wartime and those who grew up or were been born after the war. As the older generation passes, some neonationalists feel the need to bequeath to the younger generation “heroic” memories of the war that have been forgotten. The Yushukan’s mission to reestablish the linkage between the national subject and the individual can also be understood as a reaction to globalization in contemporary Japan. One of the visible signs of this is the growing visibility of postcolonial Asia along with the influx of Asian pop cultures and migrant populations from surrounding Asian countries. Postcolonial Asia threatens to disrupt the putative wholeness of the citizenship project that neonationalists attempt to maintain. The Yushukan is the showcase for an ethnic-based reactionary nationalism which retreats to the military tradition, a symbol of loyalty to and sacrifice for the nation, at the moment when the idea of the nation based on ethnic homogeneity is being undermined by domestic and international transformations.

Juxtaposing Korea and Japan, we see interconnected discourses of ethnic nationalism. Comparing war memorial museums in Japan and Korea, I have suggested that despite their antagonistic discourses, they display similar strategies of representation: staging a ritual dedicated to the war dead as an embodiment of national identity. The dispute over the museums suggests a change in the social and political landscapes of Korea and Japan. However, the public in both countries, although critical of militarism, still seems to take for granted the core idea of ethnic nationalism, which often develops into xenophobic sentiment toward “non-ethnic” Koreans or Japanese and migrant foreign workers. The unchallenged concept of nation and citizenship based on an ethnic collectivism poses a critical obstacle to the task of reconciling historical injustice between nations as well as within them. Without critical self-reflection regarding the exclusive and aggressive nature of ethnic nationalism, it will be difficult to move ahead. In this essay, rather than placing the two war memorial museums in the category of colonized versus colonizer or victim versus victimizer, I have paid attention to their similar ambition to exhibit the nation bounded by ethnic, not civic, sentiments. They urge citizens to be exclusively Koreans or Japanese and to unquestioningly identify themselves with the ethnic national community. Such visions can best be countered by recognition of the terrible price that Koreans, Japanese and Asian people have borne as a result of colonialism and aggressive wars, including those waged in the name of nationalistic purity and liberation of oppressed people.

* I am indebted to Mark Selden for critical comments on an earlier version of this article.

Notes

[1] In Korea, they include the Independence Museum of Korea (1987), War Memorial of Korea (1994), Sodaemun Prison Museum (1995), and Dongduchon Municipal Museum of Freedom, Defense, and Peace (2002). In Japan, most peace museums were built or renovated in the 1990s, including the Osaka International Peace Center (1991), Kyoto Museum for World Peace (1992), Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (1994), Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum (1996), Showakan in Tokyo (1999), Peace Memorial Center (Heiwa Kinenkan) in Tokyo (1999), Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum (2000), and Yushukan in Tokyo (2002). In China, major memorial museums including The Memorial Hall of the People’s War of Resistance Against Japan, The Memorial to Victims of the Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders, The Crime Evidence Exhibition Hall of Japanese Imperial Army Unit 731, and The September 18 History Museum were built in the 1980s and 1990s. See Yoshida, “Revising the Past, Complicating the Future: The Yushukan War Museum in Modern Japanese History” and Denton, “Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating the Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums.” The proliferation of memorial museums in Korea and Japan can be situated in the rise of the discourse of memory which, according to Andreas Huyssen, “has become a cultural obsession of monumental proportions across globe.” The discourse of memory was energized in the 1980s by the broadening debate about the Holocaust and accelerated in post-communist Eastern Europe, post-Apartheid South Africa and various post-dictatorship countries. See Huyssen, “Present Pasts: Media, Politics, Amnesia.”

[2] Anderson, Imagined Communities, 205.

[3] Anderson, Imagined Communities, 205.

[4] My thinking about nationalism and the war dead in this chapter owes much to Anderson’s “Replica, Aura, and Late Nationalist Imaginings” and “The Goodness of Nations” in The Spectre of Comparisons, 46–57, 360–368.

[5] See the War Memorial of Korea, WMK catalogue (English edition), 5.

[6] My approach to the museum draws on Carol Duncan’s analysis of the museum as a modern ritual in which visitors are prompted to enact and internalize the values written into the exhibitionary script. See Duncan, Civilizing Rituals.

[7] See Lie, Multiethinic Japan; Oguma, A Genealogy of ‘Japanese’ Self-Images; and Sato, “The Politics of Nationhood in Germany and Japan.”

[8] Befu has emphasized that nihonjinron constitutes a broadly based ideological stance for Japan’s nationalism. See Befu, “Nationalism and Nihonjinron,” p.107.

[9] Indeed, the shrine still has a strong association with the state, as evidenced by the controversial visits to the shrine by prime ministers and cabinet members. The renovation of the Yūshūkan was extensively funded by the Japan Bereaved Families Association, a private organization that is closely connected to the conservative Liberal Democratic Party.

[10] Jonjaeng kinyomgwan konlipsa, 55-73.

[11] Jonjaeng kinyomgwan konlipsa, 436–37.

[12] War Memorial of Korea, 5.

[13] Shin, “Nation, History and Politics: South Korea.”

[14] In 1989, the war museum construction committee issued an open competition for architecture design. Of the twenty designs submitted, Lee Song Jonjaeng kinyomgwan konlipsa, 181–89.

[15] The temporal sequence is also emphasized by outdoor monuments which depict the military tradition from the first century to the present.

[16] For a reflection on national cemeteries, see Anderson, “Replica, Aura, Late Nationalist Imaginings,” 46-57; and Laqueur, “Memory and Naming in the Great War.” 150-167.

[17] The National Memorial Cemetery enshrines those who sacrificed themselves for the defense and development of the nation. Established in 1956 as a military cemetery for the war dead from the Korean War, in 1965 it was elevated to the national cemetery and included patriots who fought for the liberation of the country and men of merit who sacrificed their lives for the country. It is also a ceremonial site for national anniversaries and is regularly visited by politicians to demonstrate their allegiance to the nation. Since the late 1990s, however, the status of the cemetery as the only national sanctuary has been challenged by the establishment of new national cemeteries. For example, the 4.19 cemetery which buried those killed in the protests against government corruption and dictatorship in April 1960, and the 5.18 cemetery which buried those killed in the Kwangju civilian uprising in May 1980, were rebuilt as official national cemeteries respectively in 1997 and in 2002.

[18] With no winner in the war, the ground was open for claims represent the ideal “Korea.” The museum seeks to confirm the political legitimacy of South Korea as the only legitimate son who has preserved the unbroken heritage of the Korean ethnic nation against successive foreign invasions. Even after the summit meeting between the leaders of the two Koreas in 2000, the museum’s narrative of the Korean War was little revised, as can be seen in the special exhibition, entitled “Ah! 6.25: For Freedom That Time, for Unification This Time,” held in the same year.

[19] See exhibition panels in the Expeditionary Forces Room and also War Memorial of Korea, 28.

[20] War Memorial of Korea, 42.

[21] The original project before The Statue of Brothers was The Peace Tower, a monument initiated to be a symbol of “free and democratic world” along with the WMK in 1988. The Peace Tower was designed as an abstract vertical tower 330 meters high (later adjusted to 120 meters). However, this project was cancelled in 1991 and converted to The Statue of Brothers. Both were designed by the same architect, Ch’oe Yong Jip.

[22] Jager, Narratives of Nation Building in Korea, Chapter 7, 118.

[23] Jager, Narratives of Nation Building in Korea, Chapter 7, 129.

[24] See Cumings, The South Korean Massacre at Taejon: New Evidence on US Responsibility and Cover Up,” Kwon, “The Korean War Mass Graves,” and Charles J. Hanley and Martha Mendoza, “The Massacre at No Gun Ri: Army Letter Reveals U.S. intent.”

[25] The major Peace Museums, notably those at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, seek to teach peace through documenting the nuclear destruction of the city and conveying a sense of the impact of the bombs on its citizens and the built environment. Until recently, there was no representation of Japanese colonialism or Japanese invasion of Asian countries, or even, of the United States as the nation which dropped the atomic bombs. Japanese citizens, portrayed as atomic victims, are projected as a metaphor for all human suffering in war, particularly nuclear war. Thus the museums barely mentioned the perpetrators of the violence that produced the Asia-Pacific War, with exhibits limited to the human and material consequences of the atomic bombings. The suppression of the role of U.S. in the dropping of atomic bombs entails a forgetting of the equally violent history of Japan’s militarism in Asia Pacific.

[26] Mark Selden has emphasized that the problem of Japanese nationalism needs to be located within the broader frameworks of competing nationalisms in Asia such as in China and Korea; the divisions among the people regarding memories of colonialism and war; and the Japan-US relationship. See Selden, “Nationalism, Historical Memory and Contemporary Conflicts in the Asia Pacific.”

[27] Shintoism, often referred to as Japan’s indigenous religion, centered on a reverence for deities (kami) that animistically inhabit nature. It was elevated to the state religion when the new Meiji government placed Shinto at the center of the nation’s religious and social life. The Yasukuni Shrine embodied the idea that the emperor is at the center of the religious and social life of Japanese people. With Japan’s surrender in 1945, the shrine was separated from the state. The close bonds between Yasukuni and the emperor are delineated in Takahashi, “The national politics of the Yasukuni Shrine” and Takenaka, “Enshrinement politics: War dead and war criminals at Yasukuni Shrine.” More critical articles on the politics of Yasukuni Shrine can be found in Japan Focus.

[28] For a discussion of the ritual space in the Yasukuni shrine, see Breen, “The Dead and the Living in the Land of Peace: A Sociology of the Yasukuni Shrine.”

[29] Some people commemorate the war at alternative sites, such as in the Chidorigafuchi, a national nonreligious cemetery built in 1959 to accommodate the remains of 350,000 unknown soldiers. In December 2002 a government advisory panel proposed a plan to construct a new non-religious national war memorial that would include non-Japanese war dead. This proposal sparked controversy, however, and was never implemented.

[30] See Hein and Selden, “Lessons of War, Global Power and Social Change” and McCormack, “The Japanese Movement to ‘Correct’ History” in Hein and Selden [eds]. Censoring History.

[31] See the Yushukan exhibition brochure.

[32] From the exhibition panel in the section entitled “Spirit of the Samurai.”

[33] From the exhibition panel entitled “The Korean Problem” in the section entitled “From the Russo-Japanese War to the Manchurian Incident.”

[34] From the exhibition panel.

[35] Oguma, A Genealogy of ‘Japanese’ Self-Images.

[36] See Sato, “The Politics of Nationhood in Germany and Japan,” chapter 7.

[37] See Befu, “Nationalism and Nihonjinron.”

[38] Appadurai and Breckenridge, “Museums are Good to Think,” 39.

[39] Anderson, “Replica, Aura, and Late Nationalist Imaginings,” in Spectre of Comparisons.

[40] Donga Ilbo (8 June 1993).

[41] A newspaper column deplores that “The young people visit the museum led by teachers or only to enjoy cultural events or festivals held in the outdoor plaza. For those in their thirties and the forties, the war is no longer a subject they want to talk about.” Donga Ilbo (26 June 2001).

[42] Hankyoreh (24 September 2003). They started from a campaign to publicize atrocities committed by Korean solders to Vietnamese civilians. For the on-line peace museum, click here.

[43] http://www.technoguy.pe.kr

[44] Not unlike the WMK, the Yushukan has been unpopular since it opened in July 2002. Until May 2003, approximately 226,000 individuals had visited the museum, a small number compared with the atomic bomb peace museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, each of which has received more than one million visitors every year for more than two decades. The daily newspaper Sankei reported in 2002 that no schools are currently making field trips to the museum, nor does any school incorporate the museum’s pedagogical apparatus into its curricula. See Yoshida, “Revising the Past, Complicating the Future: The Yushukan War Museum in Modern Japanese History.”

[45] Asakura, “WWII Survivors Fear Return to Warpath.”

[46] Kiroku, “Build Alternative to Yasukuni.”

[47] Moon, “Strangers in the Midst of Globalization: Migrant Workers and Korean Nationalism.”

References

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Editions, 1991.

Anderson, Benedict. Spectre of Comparison: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World. London: Verso, 1998.

Appadurai, Arjun and Carol Breckenridge. “Museums are Good to Think: Heritage on view in India.” In Ivan Karp, Christine Muller Kreamer and Steven D. Lavine [eds]. Museums and Communities: The Politics of Public culture. Washington & London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

Asakura, Takuya. “WWII Survivors Fear Return to Warpath,” The Japan Times (16 August 2002).

Befu, Harumi. “Nationalism and Nihonjinron,” in Befu [ed.]. Cultural Nationalism in East Asia: Representation and Identity. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, 1993: 107–35.

Breen, John. “The Dead and the Living in Land of Peace: A Sociology of the Yasukuni Shrine,” Mortality, 9, 1 (February 2004): 76-93.

Breen, John [ed.]. Yasukuni, the War Dead and the Struggle for Japan’s Past. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Cumings, Bruce. “The South Korean Massacre at Taejon: New Evidence on US Responsibility and Cover Up,” Japan Focus;

Denton, Kirk A. “Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating the Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums,” Japan Focus.

Duncan, Carol. Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

Huyssen, Andreas. “Present Pasts: Media, Politics, Amnesia,” Public Culture, 12, 1 (2000): 21-38.

[A Foundation history of the war memorial of Korea]. Seoul: The War Memorial Service, 1997. War Memorial of Korea, catalogue (English edition).

Laqeur, Thomas W. “Memory and Naming in the Great War.” In John R. Gillis [ed.], Commemorations: The Politics of National Identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994, 150-167.

Jager, Sheila Miyoshi. Narratives of Nation Building in Korea: A Genealogy of Patriotism. London: M.E. Sharpe, 2003.

Gluck, Carol. “The ‘End’ of the Postwar: Japan at the Turn of the Millennium,” Public Culture 10, 1 (1997).

Hanley, Charles J. and Martha Mendoza. “The Massacre at No Gun Ri: Army Letter Reveals U.S. intent,” Japan Focus.

Hein, Laura and Mark Selden. “Lessons of War, Global Power and Social Change.” In Hein Laura and Mark Selden [eds], Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany and the United States. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2000.

Kiroku, Hanai. “Build Alternative to Yasukuni.” Japan Times (27 August 2002).

Kwon, Heonik. “The Korean War Mass Graves,” Japan Focus.

McCormack, Gavan. “The Japanese Movement to ‘Correct’ History.” In Hein and Mark Selden [eds], Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany and the United States. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2000.

Moon, Katharine. “Strangers in the Midst of Globalization: Migrant Workers and Korean Nationalism.” In Samuel S. Kim [ed.]. Korea’s Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 147-169.

Nelson, John. “Social Memory as Ritual Practice: Commemorating Spirits of the Military Dead at Yasukuni ShintÅ Shrine.” Journal of Asian Studies 62, 2 (May 2003): 443–67.

Oe, Shinobu. Yasukuni Jinja. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1984.

Oguma, Eiji. A Genealogy of ‘Japanese’ Self-Images, trans. David Askew. Melbourne, Australia: Trans Pacific Press, 2002.

Sato, Shigeki. “The Politics of Nationhood in Germany and Japan.” Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 1998.

Selden, Mark. “Nationalism, Historical Memory and Contemporary Conflicts in the Asia Pacific: the Yasukuni Phenomenon, Japan, and the United States,” Japan Focus.

Shin, Gi Wook. “Nation, History and Politics: South Korea.” In Pai and Tangherlini [eds]. Nationalism and the Construction of Korean Identity. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 1998: 148–165.

Takenaka, Akiko. “Enshrinement Politics: War Dead and War Criminals at Yasukuni Shrine,” Japan Focus.

Takahashi, Tetsuya. “The National Politics of the Yasukuni Shrine,” Japan Focus.

Yoshida, Takashi. “Revising the Past, Complicating the Future: The Yūshūkan War Museum in Modern Japanese History,” Japan Focus.