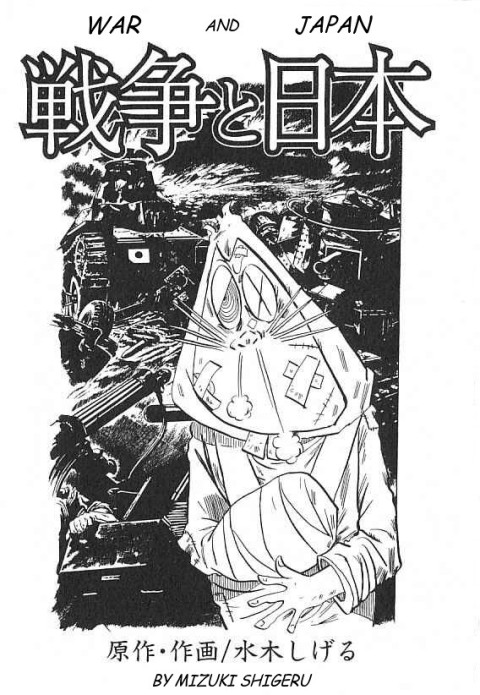

War and Japan: The Non-Fiction Manga of Mizuki Shigeru

Matthew Penney

Many Japanese neonationalists contend that it is “masochistic” to look critically at the nation’s wars of the 1930s and 1940s. They assume that criticism of Japanese militarism and love of the country and its traditions are somehow mutually exclusive. In place of an honest look at past crimes, revisionists present Japan as a victim, originally of Western imperialism, and now of a conspiracy of defamation by its neighbors.

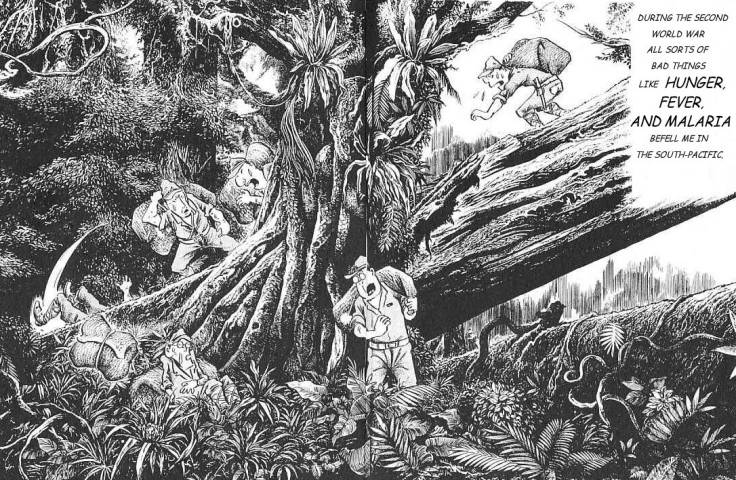

Manga artist Mizuki Shigeru (b. 1922), creator of the famous supernatural series GeGeGe no Kitaro, is one individual who could not be blamed for feeling like a victim. A veteran of the fighting in the South Pacific, Mizuki was felled by malaria and lost his left arm in an American air raid. He suffered life-long health effects from the abuse he endured as a new recruit. Mizuki, however, has not slipped into a comfortable “victim’s view” of the war. Through non-fiction manga, Mizuki has explored the full range of Japanese war experience, seeking to reconcile images of Japanese as victims of their own elites and victimizers of others.

Mizuki in front of drawings of some of his most famous characters

Mizuki is also one of postwar Japan’s most prolific and influential interpreters of traditional ghost stories and folklore. He wrote that he wanted Japanese ghosts, previously thought of as grotesque or the products of an undignified plebian tradition, “… to be loved like fairies.” [1] His work has contributed to an enduring boom in interest in Japanese folktales. Mizuki, who unlike most prominent revisionists actually experienced the horrors of war firsthand, sees no contradiction between a love for Japan and its traditions, and a willingness to look honestly at the nation’s war history. His war stories contain many shocking images, but he still reflects, “… on the way back to Japan from Rabaul, the moment that I saw Mount Fuji from the sea, I thought, ‘I’m back’, and I felt, ‘I’m Japanese’.” [2]

Mizuki is also one of Japan’s most honored manga artists. His home town, Sakaiminato in Tottori prefecture, is home to the Mizuki Shigeru Museum. In addition to the Mizuki Shigeru Road in Sakaiminato – a major tourist spot lined with bronze sculptures of his most famous characters – a Mizuki Shigeru Road was named in Rabaul in 2003.

Mizuki Shigeru Museum

Mizuki is a difficult author to classify ideologically. For example, unlike many other progressives who consider the “Imperial System” to be an invented tradition, Mizuki describes it as central to Japan’s history and culture, “From ancient times … Japan has had gods like ike no nushi (master of the pond) and mori no nushi (master of the wood) so I think that it is safe to say that the Japanese people like this nushi idea. In a similar way, Japan’s oldest family – the Imperial Family – has watched over the people of Japan with kindness as the kuni no nushi (master of the country) and I don’t think that it is a bad system at all.”[3] He is, however, critical of the Imperial System in wartime, “… the senso-chu no nushi (master in wartime), was terrifying to me.”[4] He contextualizes this with reference to his personal suffering, “When I went to the front lines in the South Pacific, I was beaten half to death for dropping the ‘rifle gifted by his highness’.”[5] Mizuki’s historical perspectives, informed by his own experience of violence and the excesses of Japan’s wartime regime, do not fit comfortably with stereotypical “rightwing” or “leftwing” positions. Sharing elements of both, but with a strong progressive bent in the area of war responsibility, Mizuki has crafted a series of unforgettable war stories.

Mizuki has long played up anti-war themes in his work. In the 1960s, he railed against the American military’s practice of bombing civilian targets in the supernatural series Akuma-kun (Lil’ Devil, 1966-1967), a hit that helped to propel him from artistic journeyman – he got his start painting kami-shibai (‘paper plays’ – alternating pictures narrated by itinerant performers) – to a leader in the industry.[6]

Akuma-kun

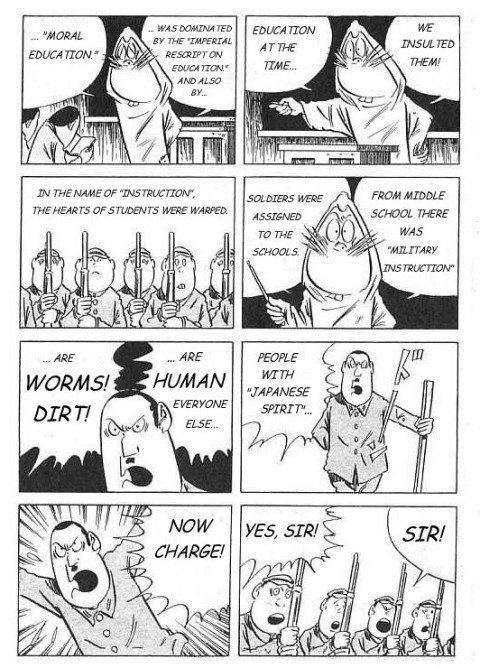

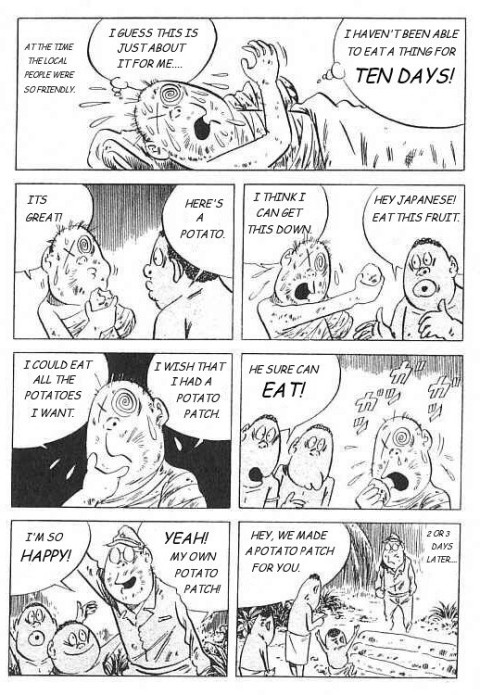

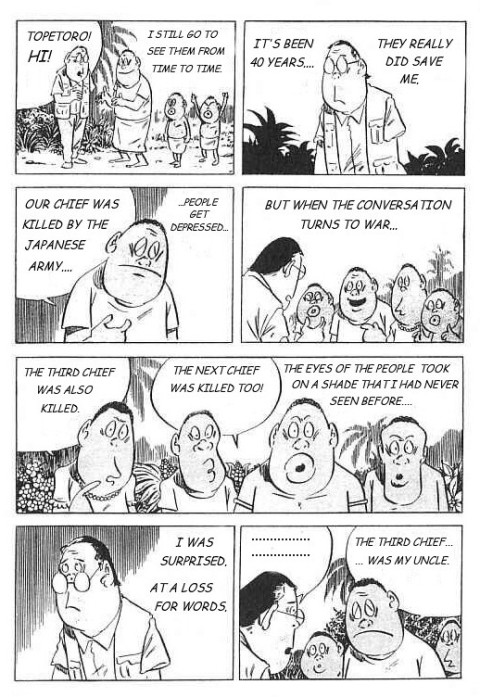

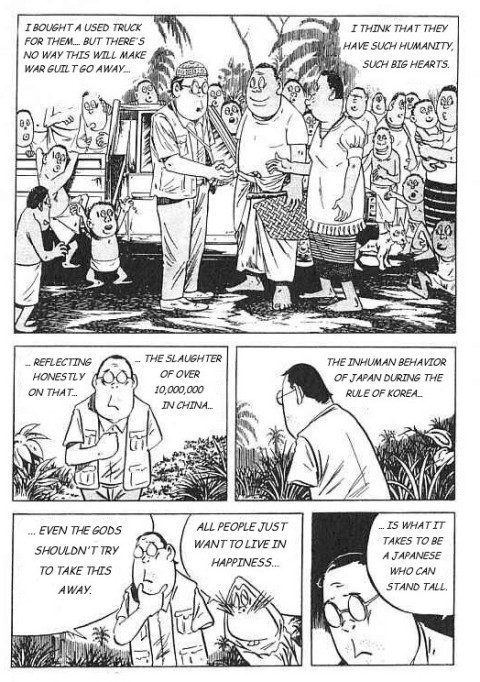

Buoyed by this success, he was also one of the handful of creators who experimented with the potential for serious non-fiction manga with Hitler (1971), a critical biography that turns a history of Nazi atrocities into a forceful anti-war parable for Japanese readers.[7] From the 1970s he began to win critical acclaim with a series of autobiographical war stories such as Soin Gyokusai Seyo! (Death to the Last!, 1973), focusing on the abusive treatment of Japanese recruits and the cavalier attitude of their officers toward human life.[8] He has also consistently put forward positive images of South-Pacific Islanders, contrasting their charity and humanity with the brutality of the Japanese forces.

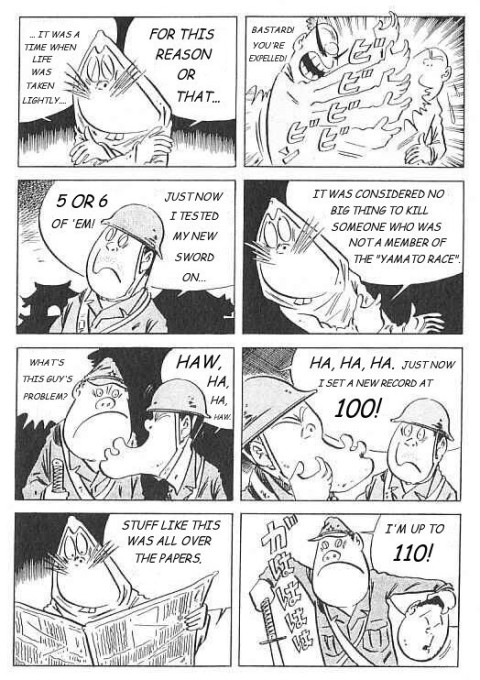

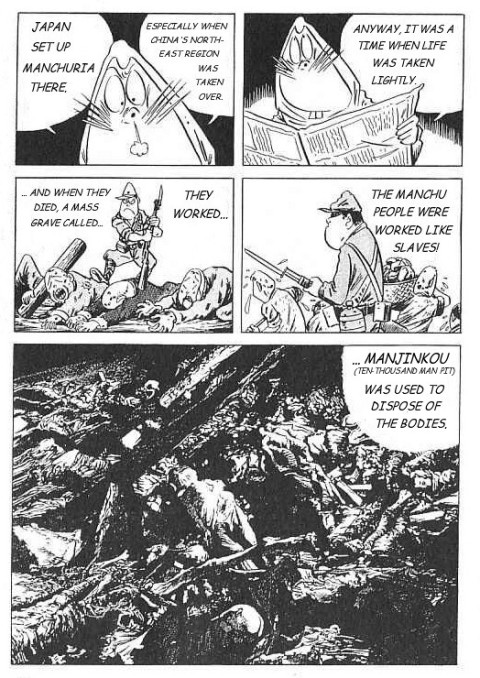

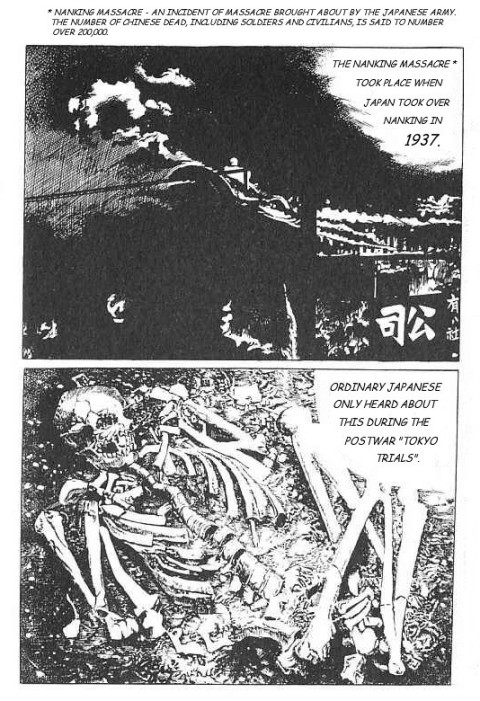

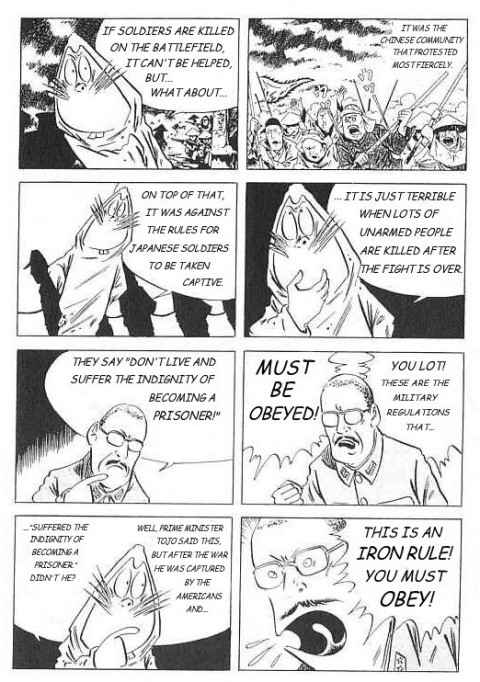

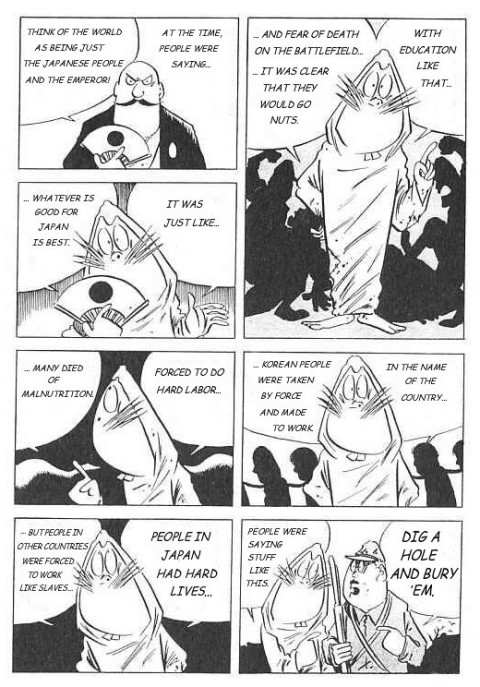

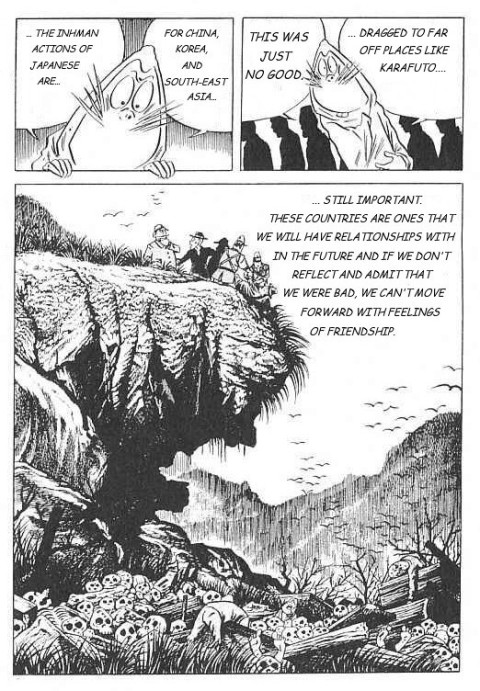

In the late 1980s, Mizuki’s war manga took a different direction as he attempted to synthesize his own personal experiences with the grand narrative of Japan’s modern history in Showa-shi (History of Showa).[9] This series, despite (or perhaps because of, given a spike of interest in the war period) graphic images of the Nanking Massacre, descriptions of forced labor, and other Japanese war crimes, became a bestseller and was awarded the Kodansha Manga Prize, one of the industry’s highest accolades.[10] A critical view of Japan’s wartime past was no impediment to success. Not only has Mizuki avoided significant criticism by the rightwing, possibly due to his iconic status and personal war experience, but he has also been the recipient of some of the Japanese government’s most prestigious awards – the Shiju Hosho (Purple Ribbon Medal) in 1991 and the Kyokujitsu Sho (Order of the Rising Sun) in 2003.

Mizuki’s collection Air War

Below is a translation of Mizuki’s “War and Japan”, a short work in the style of Showa-shi, originally published in 1991 in Shogaku rokunen-sei (Sixth Grader), a leading edutainment magazine for young readers. The difficulty of the material presented raises a number of important issues. Japanese children are not passive receptacles of government-sponsored narratives. The varied perspectives in popular culture are also important. Many of Japan’s most famous manga creators, including Mizuki, Tezuka Osamu, Nakazawa Keiji and Ishinomori Shotaro, have penned honest and challenging war stories. These serve as a powerful counterpoint to revisionist manga like Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron (On War) that have grabbed attention in the English-speaking world.[11] Several neo-nationalist manga have sold well, but a wide variety of progressive titles have also been successful. Importantly, anti-war themes introduced into the medium by Mizuki and others have helped to shape the trajectory of postwar manga. Explicitly apologist and pro-war titles like Sensoron may be shocking, but their success is dwarfed by that of anti-war visions like Arakawa Hiromu’s current hit Hagane no renkinjutsu-shi (Full Metal Alchemist) which uses a science fiction setting to interrogate organized violence and atrocities.[12]

Order the Japanese original of Mizuki’s war memoir manga Aa Gyokusai here.

Arakawa’s Hagane no renkinjutsu-shi

Specific criticisms of Japan’s wartime order are also prolific as in Senso no shinjitsu (The Truth of War), an August 2008 anthology that uses the visual grammar of shojo (girl’s) manga to look at war from a variety of angles, including atrocities committed by Japanese forces.[13] Mizuki’s “War and Japan”, however, is unique in its simple, accessible diction, and thoughtful, autobiographical conclusion. Describing his motives for turning his war memories into manga, Mizuki writes, “I saw too many comrades die. Even now, I sometimes catch a glimpse of the shades of dead friends standing at my bedside… When I think of those who, now without voice, died pitifully in war, I am overcome with anger.”[14] Mizuki thinks first of the deaths of those close to him, but he never allows this to settle into a simple “Japanese as victims” theme. As “War and Japan” demonstrates, the anger that he feels extends to those responsible for all victims of Japan’s wars.

Notes

[1] Mizuki Shigeru, Honjitsu no Mizuki-san (Today’s Mr. Mizuki), Tokyo: Soshisha, 2005, p. 98.

[2] Ibid., p. 39.

[3] Ibid., p. 39.

[4] Ibid., p. 39.

[5] Ibid., p. 135.

[6] Mizuki Shigeru, Akuma-kun, Tokyo: Kodansha, 2008.

[7] Mizuki Shigeru, Hitler, Tokyo: Chikuma Shoten, 1990.

[8] Mizuki Shigeru, “Soin Gyokusai seyo!” in Aa Gyokusai (Ah, Death to the Last), Tokyo: Ozora Shuppan, 2007.

[9] Mizuki Shigeru, Showa-shi, Vol. 1, Tokyo: Kodansha, 1989.

[10] Shimura Kunihiro, Mizuki Shigeru no miryoku (The Charm of Mizuki Shigeru), Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, 2002, p. 43.

[11] Kobayashi Yoshinori, Sensoron, Tokyo: Gentosha, 1998. See also Rumi Sakamoto, “Will you go to war? Or will you stop being Japanese?” Nationalism and History in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron”

[12] Arakawa Hiromu, Hagane no renkinjutsu-shi, Vol. 1, Tokyo: Square Enix, 2002.

[13] Ichikawa Miu, et al., Senso no shinjitsu, Tokyo: Bunkasha, 2008.

[14] Mizuki Shigeru, “Naki senyu ga egakaseta senki manga” (War Manga that My Dead Comrades Made Me Draw) in Aa gyokusai, Tokyo: Azora Shuppan, 2007, pp., 185-186.

Matthew Penney is Assistant Professor at Concordia University and a Japan Focus associate. He is currently conducting research on popular representations of war in Japan. He can be contacted at [email protected].

He wrote and translated this article for Japan Focus. Posted on September 21, 2008.

Note – Apart from the title page, this manga should be read (the speech balloons and panels followed) from RIGHT to LEFT.

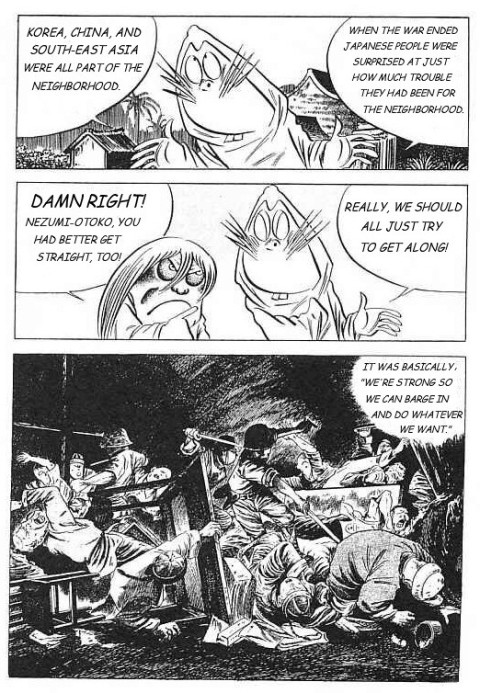

The narrator of “War and Japan” is Nezumi-Otoko (Mouse Man), a famous character from GeGeGe no Kitaro.

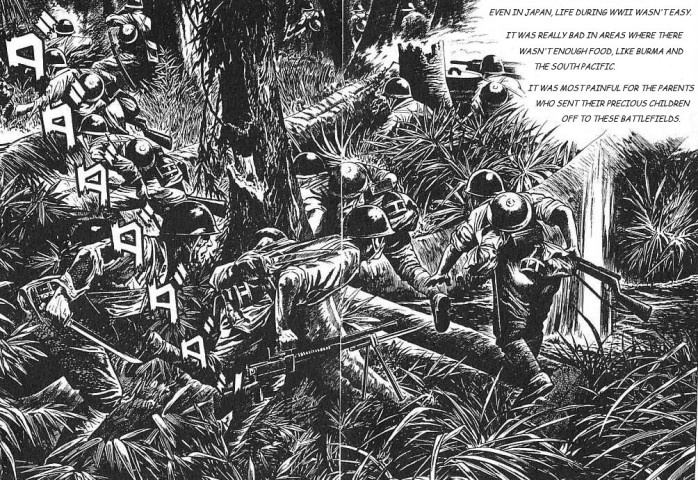

Even in Japan, Life During WWII Wasn’t Easy.

It was really bad in areas where there wasn’t

enough food, like Burma and the South Pacific.

It was most painful for the parents who sent their

precious children off to these battlefields.

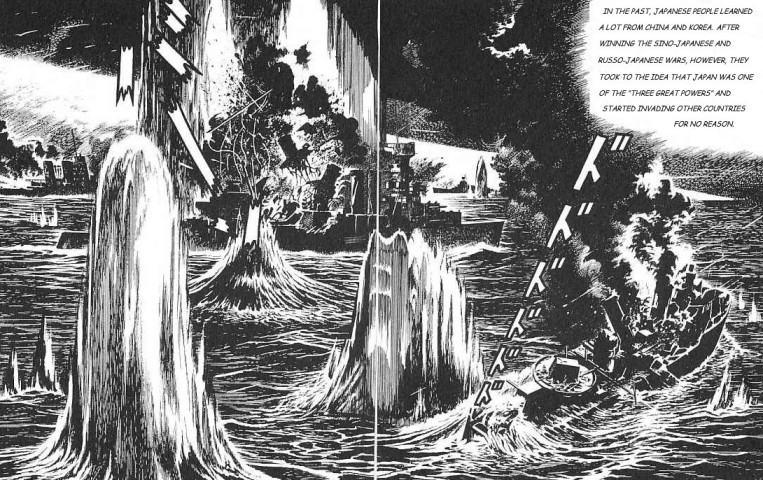

In the past, Japanese people learned a lot from China and Korea

After winning the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, however,

they took to the idea that Japan was one of the “Three Great Powers”

and started invading other countries for no reason.

During the Second World War all sorts of bad things

like HUNGER, FEVER, AND MALARIA befell me in the South Pacific.