Japan’s Yasukuni problem is inseparable from the fact that nationalism is the dominant ideology of our era. This is abundantly clear in media representations, memorials, museums and popular consciousness during and after wars and other international conflicts. [*] This is true not only of Japan but also of South Korea, China and the US, among many others. And it is surely nationalism—stimulated and emboldened throughout Asia following the end of the era of US-Soviet confrontation, the rise of China as a regional and world power, and aggressive US actions associated with the “war on terror”—that constitutes the most powerful obstacle to resolution of the issues that divide nations and inflame passions in the Asia Pacific and beyond. Throughout the twentieth century, nationalism has everywhere been the handmaiden of war: war has provided a powerful stimulus to nationalism; nationalism has repeatedly led nations to war; and war memory is central to framing and fueling nationalist historical legacies. This article considers Yasukuni Shrine and Japanese war memory and representation in relationship to contemporary nationalism and its implications for the future of East Asia.

The contentious issues that continue to swirl around war, memory, and representation are central to shaping nationalist thought, the future of Japan, the Asia-Pacific region, and the US-Japan relationship. Why do issues such as the role of Yasukuni Shrine repeatedly surface six decades after Japan’s defeat even as the generation that experienced the war is passing from the scene? This seems all the more counterintuitive at a time when the economies and even the cultures of China, Japan and Korea are deeply intertwined.

The “Yasukuni problem” is at the epicenter of the complex set of issues surrounding Japanese wars in the Asia Pacific, the emperor, religion, and identity. Yasukuni issues are deeply intertwined with China-Japan, Korea-Japan and the US-Japan relationship. Attention to Yasukuni reveals distinctive characteristics of Japanese nationalism while allowing us to explore a number of themes of comparative nationalism.

It is important to state clearly at the outset the reason for undertaking this analysis: it is to search for ways that might contribute to mutual understanding among the nations and peoples of the Asia Pacific, including Japan, China, Korea and the United States.

I will emphasize three points about the “Yasukuni Problem” and contemporary nationalisms that seem absent in much of the discussion in Japan, Asia and internationally. The first is the need to transcend an exclusively Japanese perspective by locating the issues within the framework of the Japan-US relationship that has dominated Japanese politics for more than six decades. The second locates war nationalism in general and “Yasukuni nationalism” in particular within the broader purview of competing nationalisms in the Asia Pacific, including Chinese, Korean and US nationalisms. The third deconstructs “the Japanese,” to recognize deep fissures among the Japanese people with respect to Yasukuni, nationalism, the emperor in whose name Japan fought, and memories of colonialism and war. Each of these requires breaking with a monolithic understanding of the issues. Each has implications for moving beyond the present political impasse and reflecting on approaches that could contribute toward tension reduction in the Asia Pacific.

Yasukuni Jinja both is and is not a “Japanese” problem. As a Shinto shrine with enduring historical links to the emperor—established in 1869 “to commemorate and honor the achievement of those who dedicated their precious life for their country”—and with a deep association with every Japanese war from the Meiji era through the Asia Pacific War, it evokes Japanese tradition linking Shinto, emperor and war. [1] Yet to see it simply as Japanese is to neglect a range of features characteristic of contemporary nationalisms. This view ignores important regional and global forces, particularly the role of the United States, in shaping politics and ideology from the Japanese occupation to today.

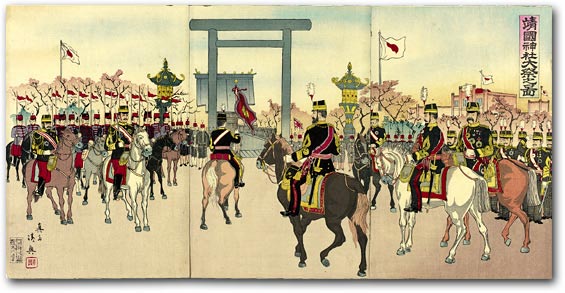

Yasukuni Shrine in a Meiji woodblock

Yasukuni shrine layout today

Japanese neonationalists insist on the quintessential Japanese character of Yasukuni, thereby attempting to place it beyond discussion by people in neighboring and other countries, as well as seeking to crush debate within Japan. But they are not alone in their stress on Japaneseness. In calling for a politics of pride, their scorn for the Tokyo Trial and other international assessments of Japanese war crimes, and their insistence that the era of apologies to victims of Japanese war atrocities should end, contemporary Japanese nationalists share something with certain Japanese progressives and pacifists. Whether praising former Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s high profile visits to Yasukuni and defending the legitimacy of the Yushukan museum exhibits, which glorify the exploits of the Japanese military in the Asia Pacific War and praise Japan for liberating Asia from European colonialism, or criticizing them as an illegitimate attempt to reverse historical verdicts and a slap in the face to Japan’s neighbors, both nationalists and progressives routinely present Yasukuni as a uniquely Japanese phenomenon.

Yasukuni, Commemoration and the US-Japan Relationship

Yasukuni is, of course, quintessentially Japanese in its mix of Shinto and emperor lore, its architecture and rituals that apotheosize the military war dead as kami (deities), and its nationalist perspective on colonialism and war, emperor, and the souls enshrined there.

Yasukuni Shrine festival 1895. Woodblock print by Shinohara Kiyooki. Reproduced from M.I.T. Visualizing Cultures.

As Yomiuri Shimbun’s editor Watanabe Tsuneo commented tartly of the exhibits at the Yushukan museum on the shrine grounds, “That facility praises militarism and children who go through that memorial come out saying, ‘Japan actually won the last war.’” [2] More precisely, the exhibits, centered on the devotion of the military to emperor and nation, elevate Japan’s war making to aesthetic and spiritual heights, embracing the imperial mission and lionizing the kamikaze pilots sent to sacrifice themselves for emperor and nation.

Throughout the war years (1931-45), indeed from the Meiji era forward, Yasukuni Shrine was the centerpiece of what Takahashi Tetsuya has termed the “emotional alchemy” of turning the grief of bereaved families into the patriotic exhilaration of enshrinement of the war dead as deities with the stamp of official recognition of personal sacrifice and honor by the emperor.

Hirohito at Yasukuni Shrine in 1935

It is an alchemy sealed in Japanese government payments to deceased soldiers’ families that for six decades has forged a bond between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and a powerful constituency, while implicitly legitimating the aims of colonialism and war for which so many Japanese soldiers and civilians died. [3]

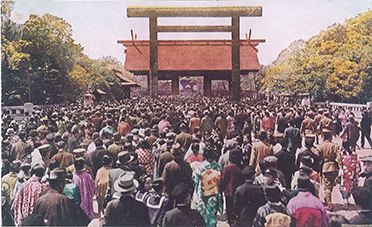

A festive crowd throngs the shrine in 1940

Another kind of alchemy goes hand in hand with the alchemy of exaltation. This is the alchemy of amnesia . . . forgetting atrocities and war crimes, forgetting the treatment of the military comfort women, of forced laborers, of those whose lands were invaded, homes destroyed and families slaughtered in the name of emperor and empire. While the military dead were enshrined as kami at Yasukuni shrine and their families received state pensions, the hundreds of thousands of civilian dead and many more injured were forgotten: neither shrine nor state commemorated their sacrifice or attended to the needs of their families. If nationalism has everything to do with invented tradition, as Benedict Anderson has compellingly argued, it is equally about suppressed or forgotten traditions.

All nations symbolically elevate the sacrifice of the military war dead—their own dead—a compact to secure the compliance of soldiers and civilians to fight and die for goals proclaimed by the state. [4] If the symbolism of Yasukuni is distinctive in its particulars, it is but one such manifestation of a global phenomenon of state-sponsored war nationalism pivoting on the military war dead. With the enshrinement of Japan’s 2.46 million military dead, the senbotsusha, that is, all who died in uniform from Meiji through the Pacific War (2.1 million in the Pacific War), Yasukuni reinforced its position as the central symbol linking emperor, war, the military and empire. John Breen’s sensitive analysis of the shrine’s rites of apotheosis and propitiation well documents the nexus of power and ideology that gives the shrine its special place in contemporary Japan. [5]

Chinrei-sha, Spirit-pacifying shrine

Okinawa, Japan, the United States and the War Dead

Okinawa provides another vantage point from which to assess the Yasukuni phenomenon, and not only because the Battle of Okinawa, the only major campaign fought on Japanese soil, was the costliest of the Asia-Pacific War in terms of Japanese, Okinawan and American lives. The Battle has also played a crucial role in framing the postwar US-Japan-Okinawa relationship and the historical memory battles that continue to this day.

The different positions of Okinawans and Japanese became patently clear in the course of the Battle, when Japanese forces compelled many Okinawans seeking shelter from the American attack to commit collective mass suicide (shudan jiketsu) rather than surrender. [6] Japanese-Okinawan differences in perspective would also shape subsequent commemoration and memory practices in the form of controversies over monuments, museums, films, manga, and textbook interpretations.

With an estimated 250,000 deaths the Japanese state, including 150,000 Okinawans (more than one-fourth of the civilian population) and 100,000 Japanese forces, as well as 12,000 US troops, the battle turned central and southern areas of the main island into a wasteland. Even while the fighting raged, US forces sequestered large areas of central Okinawa and began constructing airfields, roads and bases. Indeed, as early as 1947, as Takemae Eiji observes, “more than one third of Okinawa’s arable surface lay under roads and runways or behind barbed wire.” [7] When US authorities resettled residents of these areas to the south, the settlers encountered the bones of the war dead lying scattered on the ground. [8]

Immediately following resettlement, community-organized bone collection campaigns (ikotsu shushu) were waged to make the former battlefield livable and to conciliate the spirits of the dead. Bones were washed and then cremated or placed in newly built ossuaries scattered throughout Southern Okinawa. The remains of 135,000 people were collected between 1946 and 1955. In the most celebrated case, the 4,300 residents of Mawashi Village who were resettled in Miwa Village, painstakingly collected the remains of 35,000 people and deposited them in an ossuary at Konpaku-no-to, which became, and remains today, the major site for local commemoration of the Battle, and above all for the losses of the Okinawan people civilians as well as soldiers.

Konpaku is not, however, Okinawa’s only major commemorative site. In July 1957, the Relief Section of the Government of the Ryukyu Islands established a central ossuary at Shikina, transferring war remains from small ossuaries and shipping identifiable Japanese remains to the mainland. The inaugural memorial service for Shikina was held on January 25, 1958. The US authorities, with deep misgivings, permitted three representatives from Yasukuni Shrine, two Diet members, and a representative from the Prime Minister’s Office to attend. There were also representatives of the Okinawa Bereaved Families Federation, which, like the national organization, lobbied for closer relations between the Okinawan war dead and Yasukuni Shrine, as well as Japanese government subsidies for, and official visits to, Yasukuni. [9] In short, US efforts to sever the Ryukyus from Japan were thwarted by means of linkages between Okinawan and mainland Japanese commemorative practices that linked the Okinawan dead to Japan, and specifically to Yasukuni Shrine.

If Konpaku was the creation of Okinawan villagers, Shikina was primarily the product of GRI (that is, the US administration of the Ryukyu Islands) under pressure from Tokyo. Yet we cannot simply conclude that Konpaku embodied Okinawan sentiment while Shikina was the expression of Tokyo and/or the US. Both sites honored the military and the civilian dead, Japanese and Okinawan, although as we will note, with quite different emphases.

In the wake of the establishment of the Shikina commemorative site, the Japanese government moved vigorously to consolidate its territorial claims to Okinawa, still a US military colony, through establishing prefectural memorials to the military dead. Six prefectural monuments were built between 1954 and 1963, then thirty-nine more between 1963 and 1971, nearly all in the vicinity of Shikina on Mabuni Hill.

With the prefectural monuments close to those honoring Generals Ushijima Mitsuru and Cho Isamu, commanders of the Japanese 32nd Army who committed suicide at Mabuni Hill, the Japanese military and the state placed its imprint on Okinawan soil and bid to create a unified military-centered war memory for both Japanese and Okinawans. That memory highlighted loyalty to the emperor and reification of the war mission as exemplified by the choice of suicide over surrender.

The Japanese government, displaced from Okinawa by US forces, worked to lay claim not only to the souls of mainland Japanese soldiers who died, but also to those of Okinawan soldiers and even civilians. USCAR documents record the fact that in January 1964 “the Japanese cabinet decided to confer court ranks and decorations posthumously to World War II war dead, including approximately 52,700 Ryukyuan (Okinawans).” [10]

Who were the Ryukyuans chosen to receive court ranks and decorations, and did they in fact receive them? Were Okinawan civilians among those enshrined at Yasukuni . . . hitherto reserved for the military dead? Figal does not provide definitive answers and further research has yet to resolve the issue. It seems likely, however, that Ryukyuan civilians, notably the 580 members of the Himeyuri (Maiden Lily) student nurse corps and the 2,000 strong Blood and Iron Corps, comprised of junior high and high school students, called up during the Battle of Okinawa and mythologized by the Japanese government for their loyalty, were among those who were slated for honors. [11]

In short, even while Okinawa remained a US military colony, albeit with recognition that Japan possessed residual sovereignty, Japanese authorities moved to lay claim to the souls of the Okinawan war dead (military and civilian), while memorializing and apotheosizing fallen Japanese soldiers.

Following Okinawa’s reversion to Japanese administration, on May 15, 1972, the Okinawa Battle Site Governmental Park established by GRI was renamed the Okinawa Battle Site National Park and the entire area around Mabuni Hill became the Peace National Park.

It is widely believed that Japan has no national cemetery, or that Yasukuni Shrine functions in effect as a national war cemetery that preserves no remains of deceased soldiers. But in 1979 the Shikina Central Ossuary that housed the remains of the unknown war dead was replaced by the National Okinawa War Dead Cemetery (NOWC) at Mabuni Hill. With the war remains transferred from both Konpaku-no-to, the local ossuary, and from Shikina, NOWC became Japan’s first and only national cemetery. Figal shows how the cemetery expanded beyond its Okinawan roots to become a national sacred site that commemorates all of Japan’s Asia Pacific War dead:

Prefectures enshrined the spirits of the war dead from all south seas campaigns and in some cases from continental Asia as well, transforming the form and function of memorial space in Okinawa from its local roots around Komesu to a national shrine centered at the site where the Japanese commanders committed ritual suicide on 23 June 1945.

The cemetery is a mecca for Japanese tour groups, including military groups organized by unit and by prefecture, paying homage not only to the war dead from the Battle of Okinawa, but also to the Asia Pacific War, one celebrating the emperor-military bond.

Following the election of Ota Masahide as Governor in 1990, Okinawa moved to create the Cornerstone of Peace (Ishiji) at Mabuni Hill, inscribing in stone the names and nationality of the 239,000 combatant and noncombatant dead of all nations: Japanese, American, Korean, Taiwanese, British, and Okinawan among others. This cosmopolitan and inclusive approach, with its distinctive Okinawan roots and close attention to the civilian victims of the Battle, stands out among the world’s memorials. The Cornerstone contains this inscription looking beyond the nationalist passions of war: “The Cornerstone of Peace” is a place to remember and honor the 200,000 people who lost their lives in the Battle of Okinawa and other battles, to appreciate the peace in which we live today and to pray for everlasting world peace.”

Cornerstone of Peace. More than 237,000 names of deceased civilians and soldiers are inscribed.

Yet for all its universalism, we note the continued stamp of the nation state in two important ways in the memorial spaces at Mabuni. First, the dead are arrayed in separate areas by nationality, and with Okinawans distinguished from mainland Japanese. Second, Mabuni Hill includes not only the Okinawan representations encapsulated in the Cornerstone of Peace and Konpaku-no-to, but the NOWC and the prefectural military memorials with their intimate ties to the Japanese military and Yasukuni Shrine. The mélange of memorials illustrates the conflicting approaches to commemoration between the Japanese state and Okinawan prefectural authorities. We may say that NOWC is a monument to war while the Cornerstone is a monument to peace. The Cornerstone of Peace is notable for its inclusiveness in commemorating the dead of all nations, its honoring of civilians and military victims of the Battle, and its partially successful attempt to transcend nationalist categories in search of universal peace. It is an achievement that has been realized in no mainland Japanese, American, British or German national commemorative site with which I am familiar. [12]

Yasukuni, Nationalism and Historical Memory in Postwar Japan

The postwar period brought subtle yet crucial changes in the construction of Japanese war memories. During the occupation, Yasukuni, like so much else, became a Japan-US construction with implications for the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. The Yasukuni problem is most fruitfully viewed in relation to US decisions that include the permanent positioning of US forces in Japan, the preservation of Emperor Hirohito on the throne at the symbolic center of postwar Japanese politics yet subordinate to American power, and the dismantling of state Shinto while allowing the shrine to continue as an independent religious legal entity. Yasukuni’s formal position was redefined by constitutional provisions separating church and state, yet important ritual bonds linking emperor and shrine remained intact. Because the post-war Constitution does not specify a head of state, the emperor and the imperial representative was able to patronize and visit Yasukuni, the chief priest of the shrine held regular audiences with the emperor, and the emperor’s representative played a central role in shrine rituals without raising legal issues. [13] Yasukuni Shrine was intimately associated with, and provided legitimation for, Japan’s Pacific War, enshrining those who sacrificed their lives for Japan. In the 1930s and early 1940s, visits by the emperor and by families of deceased soldiers enshrined as kami provided ideological and spiritual foundations for war and empire.

In the postwar, with Japan at peace and occupied by US forces, the shrine has played a role in structuring how the war is remembered and presented to the Japanese people. It did so within a framework crafted by the occupation authorities who exonerated the emperor of all responsibility for initiating or waging war. Indeed, Hirohito was credited by both the occupation authorities and the Japanese government with bringing peace by personally intervening to end the war. Not only would the emperor not be deposed or tried as a war criminal, he would be shielded even from testifying at the Tokyo Trial. [14] The verdict at Tokyo, sentencing Tojo and a small number of prominent military and government officials to death, as well as the convictions of thousands of soldiers and police officials tried in B and C class tribunals, in leaving untouched Japan’s supreme wartime leader, essentially absolved the Japanese people of the responsibility to examine their own behavior in the era of colonialism and war. For these reasons, the US as well as Japan ultimately shares responsibility for resolving issues of war responsibility that it helped to create, including those associated with the emperor and with Yasukuni Shrine.

During the occupation, while shorn of official ties to the state and given a ‘private’ religious status, Yasukuni Shrine remained the central national-religious symbol for those who would defend the memory of war and would deny calls from Chinese, Koreans and other victims, including GI prisoners of war, for apologies and compensation for Japanese war crimes and atrocities. [15]

Whatever its official status, the link between Yasukuni and the emperor, and between Yasukuni and the Japanese government has remained strong. Hirohito made eight postwar visits to Yasukuni, the last in 1975, firmly nurturing the bond between emperor and shrine on the one hand, and the souls of the military dead enshrined there on the other. Hirohito never paid a personal visit to Yasukuni after the October 17, 1978 enshrinement of 14 Class-A war criminals defined by the Tokyo Trial and styled “Showa martyrs” by the Shrine authorities. [16] Nor has his successor, Akihito, who has reigned since 1989, paid a public visit to the shrine. Yasukuni Shrine continues to highlight its imperial bond, as in this passage from its website: “twice every year−in the spring and autumn−major rituals are conducted, on which occasion offerings from His Majesty the Emperor are dedicated to them, and also attended by members of the imperial family.’ [17]

The symbolism linking emperor-Yasukuni-war-empire remains in place, a compelling example of what Herbert Bix calls Hirohito’s apparition. That is, regardless of whether the emperor personally visited Yasukuni, there could be no public questioning of the role and responsibility of the emperor in war and empire, or of the nexus of power linking emperor and shrine. But if the emperor ceases to pay homage publicly at Yasukuni, what sustains the shrine’s importance in the public arena?

Viewing Japan as a Monolith

International critics of Japanese neonationalism frequently present Japan as a monolithic entity, a nation that is thoroughly unrepentant about, even celebratory of its record in the era of colonialism and war. Throughout the postwar era, however, the Japanese polity has been, and remains, deeply divided over how to remember the era of colonialism and war in general, and the Yasukuni problem in particular. This explains the furor among Japanese provoked by Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s Yasukuni visits and by state approval of textbooks that reiterate neonationalist themes.

For more than half a century public sentiment in favor of the no-war clause in Japan’s Constitution, has helped prevent the ruling party, with US support, from eliminating Article 9 in order to legitimate overseas military activities. Most important, sustained popular support for Article 9 is widely recognized as one important factor that has enabled Japan, which was more or less continuously at war from 1895 to 1945, to enjoy six decades of peace and prosperity. Popular support has not, however, been sufficient to prevent the ruling coalition from steadily eroding the meaning of Article 9 by extending the regional and even global reach of Japanese military power within the US-Japan framework and to set in motion a process of Constitutional revision. Popular support for Article 9 goes hand in hand with substantial popular sentiment critical of Japan’s conduct of the Asia Pacific War and Yasukuni nationalism, a finding repeatedly confirmed in public opinion polls.

Japanese critiques of the Pacific War have not been limited to pacifists and progressives. Kaya Okinori (1889-1977), who led the War Bereaved Families Association (Nihon Izokukai), for fifteen years beginning in 1962, was finance minister in the wartime Tojo cabinet. The Association is a powerful political bulwark and lobby for Yasukuni Shrine, and, indeed for the Liberal Democratic Party, which in turn continues to support family members of deceased soldiers financially six decades after the war. Kaya served ten years of a life sentence imposed by the Tokyo Tribunal before being released and eventually taking up a post as Justice Minister. In his memoirs, Kaya condemned Japan’s war against the US and criticized his own role in the war. His most important point, no less pertinent today than when he wrote, is this: “as a Japanese, it is extremely regrettable that the people themselves could not judge the responsibility of their leaders.” [18]

Finance Minister Kaya Okinori addresses Diet Budget Committee, 1944

Despite US and Japanese policies encouraging remilitarization, significant numbers of Japanese, particularly many of the wartime generation, have long sought to make amends to Japan’s victims, most importantly by rejecting the wartime ideology of emperor-centered nationalism, colonialism and kokutai. For example, many Japanese scholars have displayed dedication, resourcefulness and courage in researching and analyzing Japanese war crimes and atrocities. Their research has made it possible to mount effective critiques of atrocities including the Nanjing Massacre and the comfort women, and to question fundamental premises of Yasukuni nationalism. Indeed, many Japanese citizens, deeply influenced by the lessons of the Pacific War and Japan’s crushing defeat, resisted militarizing trends from a pacifist perspective throughout their lives. In contrast for example to the US anti-Iraq War movement, which fizzled once the war began despite widespread continued popular disapproval of the conduct of the war, Japanese pacifism and activism have been sustained in large and small ways over decades, notably in the anti-nuclear movements. The number of privately founded peace museums, perhaps more than in the rest of the world combined, provides one measure of this. The fifty year effort by Chukiren veterans (China Returnees) who were captured and re-educated in China, and have publicly criticized their own atrocities and those committed by other members of the Japanese military ever since, is another. [19]

Critics of the revival of Japanese neonationalism have good reason to be concerned about trends of recent years, notably Japan’s dispatch of troops and ships to the Persian Gulf in support of US-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. [20] At the same time, it is important to recognize, however, that in contrast to the US, for sixty years Japan has NOT gone to war, Japanese have not killed or been killed on battlefields in Asia and beyond, proponents of Constitutional revision have not succeeded in eliminating Article 9 of the Constitution, and Yasukuni nationalism appears to be far weaker than it was in wartime.

Nevertheless, in the wake of the demise of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Socialist Party as the major opposition party, and the decline of social democracy in the face of a US-spearheaded neoliberalism, a neonationalist revival has accompanied the redefinition of the US-Japan security relationship. [21] We have suggested that Japan’s failure to adequately come to terms with its wartime aggression and the nature of its atrocities remains an obstacle to the achievement of a viable Pacific community.

The issues are not, of course, limited to Japanese intransigence, as our discussion of US war conduct has made plain. Progress on this front will also require recognition on the part of both Korea and China of the need to curb their own volatile nationalisms in the interest of a common vision for the future of the region.

Hong Kal has examined the construction of Japanese and Korean nationalisms through Yasukuni Shrine and the Korean War Memorial in Seoul. In both instances, the governments seek to cloak their legitimacy in the conduct of these wars, the Asia-Pacific War for Tokyo and the Korean War for Seoul. And in both, the presence and influence of the United States, first in its wartime role and subsequently in its postwar construction of Japanese and Korean polities, is palpable and invisible. [22] While Yasukuni nationalism reverberates throughout the Asia Pacific, the manifestations of South Korean nationalism projected in the War Memorial center on North-South rivalry.

The Political Logic of Yasukuni Nationalism and the US-Japan Alliance

For three decades, the symbolism binding the state and Yasukuni—and the heart of the Yasukuni controversy internationally—has been intimately linked with official Prime Ministerial visits that began with Nakasone Yasuhiro in 1987 and continued with Koizumi Junichiro’s annual visits in the years 2001-2006. Also important, albeit off stage, is the continuing ritual bond solidified by the central presence of the imperial representative in all important shrine ceremonies.

Since 1970, on a number of occasions historical issues centered on the China-Japan War, atrocities, and the Yasukuni shrine have fueled conflict. The China factor has grown in importance and complexity for Japan in recent decades as China emerged as a major power and competitor in Asia and as economic relations among China, Japan, South Korea and the US rapidly expanded. Indicative of the stakes are the fact that in spring 2008 China replaced the United States as Japan’s leading trade partner while Japan was China’s number three partner, with bilateral trade totals of $237 billion. [23]

Prime Minister Koizumi’s annual Yasukuni pilgrimages were among the three central symbolic and practical international actions of his five-year tenure, together with his visits to North Korea and the dispatch of Japanese ground troops [GSDF] to Iraq, as well as naval forces [MSDF] and air forces [ASDF] to the Persian Gulf. The Yasukuni visits affronted not only China and Korea, but also the people of other Asian nations and the United States. [24] They may also have firmed Koizumi’s political base in Japan even while sparking controversy. Paradoxically, it is precisely because Koizumi moved so determinedly to lash Japan to US regional and global strategic designs that Yasukuni loomed so large for him. While Koizumi’s successors have wisely refrained from visiting Yasukuni so as to avoid provoking China and Korea, they have continued to embrace growing Japanese subordination to US power, sought to expand Japan’s military reach within the US-Japan framework, and supported neonationalist calls for textbooks that elide reference to Japan’s war atrocities. This is evident in former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s passage of a new education law and measures setting in motion the process to amend the constitution.

One result of Prime Minister Koizumi’s annual Yasukuni visits, and, to a lesser extent, the battles over Japanese textbook nationalism, was that relations soured and five years passed without a meeting at the highest levels of the Chinese and Japanese leadership between 2001 and 2006. [25] This was also a period in which other Japan-China conflicts, notably the Diaoyutai/Senkaku islands territorial and oil and gas dispute flared. Japan-South Korea relations were similarly poisoned by the combination of Yasukuni nationalism and territorial disputes centered on the Dokdo/Takeshima Islets, offsetting the potentially salutary influence of the shared hosting of the 2002 World Cup and a cultural boom touched off by the unprecedented success in Japan of the Korean TV drama Winter Sonata.

The clashes in the region have gone hand in hand with challenges from a resurgent Japanese nationalism that has frequently played out around Yasukuni and related historical memory issues. Abe regularly visited the shrine on August 15, the date of Japan’s surrender, prior to assuming office. In June 2006, he firmly rejected Beijing’s call for an end to Yasukuni visits as a precondition for talks, saying “We cannot and will not allow Japan’s freedom of religion, freedom of conscience and our feeling in memory of the war dead to be violated in such a manner.” Abe nevertheless refrained from publicly visiting the Shrine during his tenure as Prime Minister, as has his successor Fukuda Yasuo.

The transition from Koizumi to Abe and Fukuda, and the growing recognition in influential sectors of Japanese business and intellectual life of the importance of China and Korea for Japan’s future, have made it possible to put aside, at least temporarily, the passionate encounters over Yasukuni and to reopen diplomatic negotiations at the highest levels. While Japanese neonationalist book and manga authors as well as filmmakers continue to reenact the Pacific War and defend the benevolence of Japanese colonial rule and vilify China and Korea, as Matthew Penney has shown, in recent years the most important Japanese books published on China have underlined Chinese achievements and paved the way toward China-Japan rapprochement. [26] As the preceding analysis suggests, however, neonationalism remains a latent and dangerous force in Japanese and regional politics.

Prime Minister Fukuda’s determination to extend the MSDF role in refueling US and coalition ships in the Persian Gulf is indicative of an expansive Japanese military within the framework of US power. The Japanese military actions in the Gulf, of course, have strategic implications both for guarding Japan’s oil lifeline from the Middle East, as well as for extending the reach of the US-Japan strategic alliance.

Gavan McCormack has observed that Japan’s deepening structural dependence and subordination requires the theatre of nationalism to make it palatable to the Japanese people. The independence that is denied in substance must be affirmed and celebrated in ritual and rhetoric. Indeed, for Japan to become the Great Britain of East Asia, as in its dispatch of GSDF, MSDF and ASDF to the war zone of the Persian Gulf, Yasukuni and other rituals of bravado, and educational efforts such as those conducted by the YÅ«shÅ«kan, are conducted to satisfy pride. [27] Nationalist bravado may conceal an overweening reality of dependence. Precisely the Koizumi, Abe and Fukuda administrations’ support for US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and for the Bush administration’s global “war on terror” buys tacit US acceptance of Yasukuni nationalism and an expansive Japanese military role while inflaming Japan’s relations with her neighbors.

At a time when many nations bridle at the Bush administration’s scorn for international norms of law and justice, as in its invasion of Iraq and the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, and in its unilateral claims to the right to intervene anywhere and everywhere, Japan’s support for US military ambitions globally increases the importance of Yasukuni as a statement to strengthen the LDP’s nationalist credentials at home. Japan places ever more of its cards on an expansive military alliance with the US, as illustrated by its extraordinary agreement to pay $6 billion (and perhaps much more) to fund the cost of transferring 8,000 US Marines from Okinawa to Guam. [28] As Japan commits to an enlarged regional military subordinate to US regional and global power projections throughout the Asia Pacific, all the more it requires more dramatic claims to nationalist credentials domestically.

The evolving character of the US-Japan alliance is well illustrated by the establishment of a forward base or regional headquarters for I Corps, the US Army’s Asia Pacific and Middle East headquarters at Camp Zama in Kanagawa, Japan. [29]In this way, the integration of US and Japanese military planning for the entire Asia Pacific is being facilitated in flagrant violation of Article 9. The US military’s five-day “Valiant Shield” exercise off Guam in June 2006 brought together US and allied Navy, Air Force, Marine and Coast guard forces involving an armada of three aircraft carriers and 25 other ships, including the Yokosuka-based Kitty Hawk group and other Japan-based ships. [30] The 22,000 troops and 280 warplanes, including the III Marine Expeditionary Force and 5th Air Force based in Okinawa, joined in the largest military exercise in the Pacific since the Vietnam War, sending powerful warning signals toward both North Korea and China. Most important, from the perspective of understanding the Yasukuni phenomenon, is that Japan’s military subordination to US power enables it to expand its military reach and ignore or flout the strong feelings of Asian neighbors, even those that are important economic partners.

Since the 1980s, China-Japan and Korea-Japan economic relationships have grown exponentially at the same time that their political relations have remained volatile. Notable are Japanese territorial conflicts with South Korea over Dokdo/Takeshima and with China over the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands and Okinotorishima Island. Tensions with both China and Korea are further inflamed by the intertwined issues of natural gas and fishing rights, as well as by war memory issues of which Yasukuni Shrine and the comfort women have been the most contentious. In June, 2008, following the visit to Japan of China’s President Hu Jintao, a China-Japan agreement was signed to jointly develop natural gas deposits in disputed areas in the vicinity of the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands. [31] In the long run, however, resolution of historical controversies is important to long-term stability and regional coordination.

Nationalism and War in the 21st Century

Many nations including Britain, France and Germany, maintain a sacred site that is the apotheosis of war nationalism. The American Shrine to war nationalism is Arlington National Cemetery, the repository of official celebration of American wars. [32] Boasting no less than 260,000 individual grave markers, the site is administered by the US Army. By contrast, Yasukuni Shrine is not a cemetery. But the names of each of the dead soldiers-turned-dieties (kami) are recorded by name in the Reijibo Hoanden (Repository for the Register of Deities).

The kami include not only Japanese soldiers, but also 50,000 Chinese, Taiwanese and Korean soldiers of the Japanese imperial armed forces, as well as tens of thousands of Okinawan civilians called to service in the final conflict on Okinawa. These are preserved as the shrine’s cultural capital and its claim to centrality in the nation’s historical and religious imagination. [33] Indeed, whereas American war nationalism requires tracking down and recovery of the remains of the dead from US combat zones, a process that continues in Korea and Vietnam decades after the end of the war, as Utsumi Aiko points out, more than one million Japanese bodies remain unrecovered and the Japanese state has done little to recover them from the battlefields of Southeast Asia and the Pacific. [34] Whereas the US has gone to extraordinary lengths and at great cost to bring back the remains of its war dead from far-flung battlefields, Japanese authorities have emphasized the enshrinement of the spirit at Yasukuni and the creation of war memorials at Mabuni Hill in Okinawa. [35]

The two sites of Arlington and Yasukuni, as well as the Okinawa Battlesite National Park, share celebratory war narratives emphasizing each nation’s just and heroic combat in all of its wars, and prioritizing of World War II/the Asia-Pacific War as the signature war in national memory. As Benedict Anderson puts it following a review of a number of sacred war memorial sites, “Each in a different but related way shows why, no matter what crimes a nation’s government commits and its passing citizenry endorses, My Country is ultimately good.” [36] Arlington, Yasukuni, and the Okinawa Battlesite Park are the sacred sites that link war and the state in nations with distinctive religious and commemorative traditions but with shared needs to recognize the sacrifice that the dead have made for the nation. One can search in vain at Arlington and at Yasukuni, for example, for any self-critical reflection on wars commemorated, above all any understanding of the plight of the victims of those wars. One finds no explanation, or even hint, of American or Japanese economic or geostrategic interests in the locales where wars were fought and whose victims the nation enshrines. Still less is there recognition of, or reflection on, atrocities or war crimes committed by Japanese or American forces in pursuit of national goals. [37] We have reviewed Japanese crimes of war above. Notable American war crimes and atrocities include the firebombing of more than sixty Japanese cities, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the use of Agent Orange and napalm to bomb Vietnamese civilians, and the systematic torture of captives in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. All were actions approved at the highest levels of government and formed integral parts of American war making. In construction a new world order following its victory in World War II, the US pioneered principles of universality of international law in the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals. But it also wielded its hegemonic power to restrict prosecution to the defeated and to deflect criticism of American war making and atrocities. In this way, it insists on US impunity to international law and international norms, including those that it helped establish and enforce. [38]

War memorials and war rhetoric celebrate the war-making prowess of the state and link the military, the nation and people in a perfect union against a common profoundly evil foe: for the US, the demonization of Al Qaeda, Saddam Hussein and the Axis of Evil are but the latest in a chain of American representational acts whose long pedigree runs from the Indian wars through the Philippines-American war of 1900 to Japan in the Pacific War years 1941-45, on to the present. The problem of nationalism becomes acute when the failure to come to terms with the dark side of aggressive and expansionist wars either paves the way for new military adventures, as in the US since World War II, or when symbolic state acts antagonize the victims of former wars, impede reconciliation, or create conditions that could prove conducive to a new cycle of conflicts, as in contemporary Japan.

We have shown a number of ways in which American and Japanese war nationalisms are intertwined as a result of US occupation policies that preserved Hirohito as emperor and permitted continuity of the Japanese government under a US-led occupation authority, paving the way for the subsequent forging of the US-Japan military alliance. Yet international criticisms of neonationalism have centered almost exclusively on Japan, the more vulnerable of the two nations, despite the fact that the US replaced Japan as the nation involved in a nearly unbroken succession of wars beyond its borders in the wake of World War II. It is surely time to recognize and analyze the character of US neonationalism rooted in structures of permanent warfare, a global network of military bases protecting both territorial and economic interests, and a claim that American wars serve to liberate oppressed people according to the formula of democracy and development. [39] In this respect, American claims resonate with long-discredited claims during the Asia-Pacific War that Japan was liberating Asia from European colonialism. Indeed they are simply the latest incarnation of the moral and developmentalist claims of colonialisms across the ages and across the globe. Today, these ideological claims rest on the institutional foundations of a global network of more than 1,000 US overseas military bases, a financial base in a military budget that is comparable to that of the rest of the world’s military budgets combined, and a strategic conception that defines a permanent “war on terror” as the US global mission. [40]

In noting the close relationship between nationalism and war, I do not wish to equate all nationalisms. In particular, I distinguish anticolonial nationalisms, that is nationalisms of resistance to invasion and colonization, such as those that took shape in China, Vietnam, and Korea in the first half of the twentieth century, from aggressive and expansionist forms of nationalism associated with colonial and post-colonial regimes and including both Japan and the United States. Nevertheless, even the nationalisms of victims that gave rise to national liberation and independence movements risk degenerating into malignant chauvinisms that can pave the way for subsequent rounds of war and block the way to regional accord. Examples include Chinese and Vietnamese nationalisms fueling the China-Vietnam border war of 1979, and contemporary Chinese and Korean nationalisms in the form of historical memory debates over the ancient Koguryo/Gaogouli kingdom on the China/Korean border that have inflamed tensions between the two nations.

From Yasukuni Politics to Tension Reduction and Regional Integration in the Asia Pacific

I conclude by looking beyond Yasukuni politics, the politics of emperor-centered Shinto nationalism and historical memories that generate confrontation politics, to reflect briefly on more hopeful regional alternatives that could promote more equitable forms of economic integration and cultural interplay.

The Asia-Pacific region is presently in the early stages of what could emerge as the third great epoch of region formation of the last half millennium. This follows on the China-centric tributary-trade order which reached its peak in the eighteenth century, an epoch of prolonged peace and prosperity in core areas of the region (but also an era in which the reach of Chinese power extended far into Inner Asia), and a Japan-centric Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere of the 1930s and 1940s, a brief and violent era of permanent war, instability and massive bloodshed. The postwar US-dominated order in Asia, like the nineteenth century European-centered colonial order, was predicated on regional fragmentation/division and the privileging of bilateral security, political and economic relationships within the US zone rather than on regional integration. It was likewise characterized by fierce military conflict, indicative of the failure of the US, like Japan earlier, to turn military supremacy into a stable hegemonic order. [41]

The US-China opening of 1970 and the resurgence of Asian economies in the final decades of the twentieth century paved the way for the re-knitting of regional bonds, the emergence of East Asia as one of the world’s three dynamic centers, and China’s reemergence as a regional and global power. This has not given rise to a regionalism of the European Union type characterized by political, security, juridical and diplomatic integration as manifest in the European parliament, a common currency, a NATO security regime, and a common judicial structure. [42] East Asian regionalism, like its postwar European variant, began to take shape within the framework of American geopolitical dominance. However, in the course of the last quarter century, regional economic integration, pivoting on China, Japan and Korea. and measured by trade, investment, and technology transfers, has proceeded rapidly, while signs abound of US decline. The US retains regional and global strategic primacy and a major economic position. But its soaring balance of payments and budget deficits, the sub-prime bubble, and the collapse of the value of the dollar against Asian and other currencies, and a costly permanent and unwinnable war on terror all point to its relative, decline.

In recent years, regional integration in East Asia has been reinforced by new levels of cultural interaction (albeit not without xenophobic reaction) involving film, TV, anime, music, sports, and manga, with cultural exchanges among China-Japan-South Korea interchanges among the most dynamic and intense. At the same time, wider efforts at regional integration have centered on ASEAN. ASEAN + 3 (China, Japan and Korea) and other variations have emerged, with China playing a vigorous regional role and Japan a far more reticent one. This pattern has been replicated in the Six-Party talks centered on the North Korea bomb and the US-North Korea relationship in which China has played a leading role while Japan remains at best a reluctant partner. Other regional formations have simultaneously appeared, notably including the Shanghai Group linking Russia, China and Central Asian nations, and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). China has led in each of these regional endeavors, while a much more prosperous and technologically advanced Japan has been content to reaffirm its subordinate ties to the US and has been slow to respond to emerging regional formations in which a resurgent China could play a major or even leading role.

Major obstacles continue to confront the realization of the cooperative possibilities inherent in the economic and cultural realms of regional cooperation in East Asia. None seem more important than the potential clash with the political and strategic dimensions of Japanese nationalism and/or the US-Japan order, both of which appear to center on curbing an ascendant China.

A dilemma confronting East Asia in the new millennium is how to mediate nationalisms that inflame historical antagonisms. To the extent that the critique of the chauvinism of others serves to privilege one’s own nationalism, the result can only be a deepening spiral of conflict. It is essential that critiques of nationalism begin, therefore, with close examination of one’s own nation: the roots and consequences of its nationalism, its record as a colonial power, an invader, and an oppressor of other peoples including ethnic minorities. This applies to Japan, the US and China, among others. This can provide a foundation for exploring the possibilities of alternative cooperative perspectives. The postwar predominance of US power has long granted Japan impunity from confronting its own atrocities and its aggressive and interventionist posture. Assessment of the Yasukuni problem, in particular one by an American, must locate the issues within the parameters of the US-Japan relationship. This requires reflection on both Japanese and American war crimes and atrocities that have yet to be recognized and effectively addressed by the Japanese or American governments in the form of apologies and compensation of victims, and ultimately in each nation’s textbooks, museums and historical monuments.

History matters. The starting point for reconciliation in the wake of wars, as the German experience amply demonstrates, lies with overcoming historical amnesia to recognize one’s own war crimes and atrocities and redress victim grievances. In the absence of steps by all parties toward overcoming the poisonous legacy of earlier wars, the Asia-Pacific region could be destined to continue to fight anew many of the still unresolved battles of a war that ended more than six decades ago but continues to reverberate powerfully in historical memory.

Notes

[*] Thanks to John Breen and Gerald Figal for advice and information, and especially to Laura Hein for relentless critique of an earlier draft of this article.

[1] The quotation is from the Yasukuni Shrine website.

[2] See the editorials by the Yomiuri and the Asahi about the Yasukuni Shrine on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Asia-Pacific War, which framed an important debate on the shrine. While the “conservative” Yomiuri and the “liberal” Asahi have frequently taken different positions on such war and peace issues as the dispatch of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces in support of the US war in Iraq, they shared a critical perspective on the question of Prime Minister visits to the shrine. The sources cited below illustrate the depth of the Yasukuni debate within Japanese society. Yasukuni Shrine, Nationalism and Japan’s International Relations. See the joint editorial by the Yomiuri and Asahi calling for a national memorial to replace Yasukuni Shrine: “Yomiuri and Asahi Editors Call for a National Memorial to Replace Yasukuni” by Wakamiya Yoshibumi and Watanabe Tsuneo. The Yomiuri also published a twenty-two part series on “War Responsibility” that remains available at their website.

It was subsequently published as a book under the title Who Was Responsible? From Marco Polo Bridge to Pearl Harbor, available in Japanese, English and Chinese editions. For an astute assessment of the Yomiuri project see Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Who is Responsible? The Yomiuri Project and the Enduring Legacy of the Asia-Pacific War,”

[3] Korean soldiers who were conscripted into the Japanese army were and remain enshrined in Yasukuni, as are indigenous people of Taiwan. However, with the loss of Japanese citizenship in 1952, surviving Korean and Taiwanese veterans were deprived of pensions. On US treatment and classification of Koreans in occupied Japan see Mark Caprio, “Resident aliens: forging the political status of Koreans in occupied Japan,” in Mark E. Caprio and Yoneyuki Sugita, eds., Democracy in Occupied Japan. The U.S. occupation and Japanese politics and society (London: Routledge, 2007), pp. 178-199; see also Yoshiko Nozaki, Hiromitsu Inokuchi and Kim Tae-young, Legal Categories, Demographic Change and Japan’s Korean Residents in the Long Twentieth Century.

[4] The same is true of groups that challenge state power through armed struggle in the name of democracy, national independence, revolution, eternal salvation, or other goals, often en route to the creation of new nations. The state then possesses and invokes goals and the memory of the martyred, as its own. The People’s Republic of China is a particularly interesting case. The state has long highlighted Chinese Communist-led resistance to Japan, both that of the army and of local guerrillas, as the central national myth, enshrined in museums and monuments. Yet there is no Chinese national cemetery which honors the war dead. See Kirk Denton’s analysis of the shift in Chinese museum representation of the Anti-Japanese resistance from the narrative of heroic resistance to one highlighting atrocities and victimization in the post-Mao years. Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating the Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums.

[5] John Breen, “The dead and the living in the land of peace: a sociology of the Yasukuni shrine,” Mortality Vol. 9, No. 1, February 2004, pp. 76-93; John Breen, ed., Yasukuni, the War Dead, and the Struggle for Japan’s Past (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

[6] Steve Rabson, Okinawan Perspectives on Japan’s Imperial Institution; Kamata Satoshi, Shattering Jewels: 110,000 Okinawans Protest Japanese State Censorship of Compulsory Group Suicides. Rabson’s analysis of Okinawan perspectives on the Battle and the emperor illuminates Okinawan understanding of Yasukuni enshrinement.

[7] Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy (London: Continuum, 2002), p. 441; casualty figures, p. 35. Wikipedia offers a useful introduction to sources on the Battle and casualties.

[8] Unless otherwise noted, this section draws on the research of Gerald Figal. “Waging Peace on Okinawa,” in Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds., Islands of Discontent. Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), pp. 65-98 and especially his “Bones of Contention: The Geopolitics of ‘Sacred Ground’ in Postwar Okinawa,” Diplomatic History, Vol 31, No. 1, January, 2007, pp. 81-109.

[9] Okinawa Izoku Rengo Kai, Ni ju go nen no ayumi (Naha, 1977), pp. 19-20, cited in Figal, “Bones of Contention,” p. 96.

[10] Figal cites USCAR, “JGLO no. II. Letter from Hisajiro Fujita, Chief Officer JGLO to Colonel William Wensboro, Acting Civil Administrator, USCAR,” 7 February 1964. OPA reference code U81100983B. See also USCAR, “Court Ranks and Decorations Will Be Posthumously Conferred on WWII War Dead,” 18 February 1964 and USCAR “Program for Conferment of Rank and Decorations to Ryukyuan War Dead,” 24 February 1965.

[11] Takemae, Inside GHQ, pp. 31-37; the photograph of two members of the Blood and Iron Corps, p. 34, shows boys in uniforms and boots who look barely twelve years old.

[12] John Breen observes (personal correspondence August 3, 2008) that the cenotaph, by its empty nature (emblematic of those whose remains are not there), suggests the possibility that the November 11 ceremony, celebrated since 1946 offers prayers for all the war dead of the two World Wars, and not just the British. The ceremony, however, featuring the Queen and other members of the royal family, together with representatives of the British government and military, suggests to me a strong national orientation.

[13] Breen, “The dead and the living,” pp. 83-84.

[14] See Herbert P. Bix, War Responsibility and Historical Memory: Hirohito’s Apparition, Japan Focus. For an historical discussion of shrine politics and the war dead see Akiko Takenaka, Enshrinement Politics: War Dead and War Criminals at Yasukuni Shrine. The case in favor of Prime Ministerial visits to Yasukuni is forcefully argued by Nitta Hitoshi, “And Why Shouldn’t the Prime Minister Worship at Yasukuni? A Personal View,” in John Breen, ed., Yasukuni, the War Dead and the Struggle for Japan’s Past, pp, 125-42. Cf. Breen’s chapter in the same volume, “Yasukuni and the Loss of Historical Memory,” pp. 143-62.

[15] Kinue Tokudome, “The Bataan Death March and the 66-Year Struggle for Justice.”

[16] Herbert Bix, in a personal note of August 21, 2008, points out that in his 1975 visit, at a moment of fierce debate over state support for Yasukuni, Hirohito was greeted by protest banners. Following the collective enshrinement of war criminals, Hirohito feared being drawn into both domestic and international conflicts involving China and Korea, and perhaps the United States.

[17] Website

[18] Wakamiya Yoshibumi, “War-bereaved Families’ Dilemma: thoughts on Japan’s war,” Asahi Shimbun, July 8, 2005.

[19] On Chukiren’s activities see David McNeill, A Foot Soldier in the War Against Forgetting Japanese Wartime Atrocities, and Linda Hoaglund, “Japanese Devils. The Perpetrators of Wartime Atrocities in China Tell Their Story in a New Film,” Persimmon, Winter 2003. On Japanese museums see Akiko Takenaka and Laura Hein, Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States.

[20] Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds., Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany and the United States (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2000).

[21] Gavan McCormack, Client State. Japan in the American Embrace, espec. Chapters 5 and 6 offer useful discussion of neonationalist currents and their embrace by the Liberal Democratic Party.

[22] “The aesthetic construction of ethnic nationalism. War memorial museums in Korea and Japan,” in Gi-Wook Shin, Soon-Won Park, and Daqing Yang, eds., Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia. The Korean Experience (London: Routledge, 2007), pp. 133-53.

[23] Reuters, May 4, 2008.

[24] BBC, “Protests Mount Over Koizumi’s Shrine Visit,” August 14, 2001. The BBC report notes demonstrations in Hong Kong and the Philippines as well as in China and Korea.

[25] Yoshiko Nozaki and Mark Selden, “Historical Memory, International Conflict and Japanese Textbook Controversies,” in press, Contexts Vol 1 No. 1.

[26] Foundations of Cooperation: Imagining the Future of Sino-Japanese Relations, Japan Focus

[27] Client State. Japan in American Embrace (London: Verso, 2007). Laura Hein analyzes both wartime and postwar Japanese nationalism as cultural nationalism predicated on the uniqueness of the Japanese spirit—a course that led the nation to disaster in the Asia- Pacific War. “The Cultural Career of the Japanese Economy: developmental and cultural nationalisms in historical perspective,” Third World Quarterly, 29, 3 (2008), pp. 447-65.

[28] That transfer is contingent, however, on the expansion of the US Air Station at Henoko, which has been stalled by Okinawan resistance for a decade. See Koji Taira, Okinawan Environmentalists Put Robert Gates and DOD on Trial. The Dugong and the Fate of the Henoko Air Station.

[29] Vince Little, “As new equipment arrives in Tokyo, I Corps begins setting up shop at Camp Zama,” Northwest Guardian, July 3, 2008. I Corps headquarters remains at Fort Lewis, Washington.

[30] See the official US Pacific Command website for Valiant Shield.

[31] Eric Watkins, China, Japan agree on East China Sea E&P projects, Oil and Gas Journal, June 20, 2008; Andre Fesyun, “China, Japan agree on East China Sea gas deposits.”

[32] John Breen emphasizes important differences between Yasukuni Shrine and Britain’s Cenotaph, France’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and Arlington Cemetery: “Yasukuni alone is a religious institution, a sacred site with its own priesthood who perform rites for the dead, propitiating them as kami. . . The Western sites are relatively ‘unencumbered’ as sites of tribute, mourning and memory. . . Yasukuni venerates the dead as kami and in the ritual process of so doing it tends to the glorification of self-sacrifice and the idealization of Japan’s imperial past.” “The dead and the living,” pp. 90-91. There are indeed distinctive differences in the ritual practice of Yasukuni, in the spiritual weight of the bonds linking shrine, emperor, the military and the nation. In the discussion that follows, I nevertheless emphasize common features in sites that link war, the sacrifice of dead soldiers, the state, and the national purpose, as well as the role of the priesthood in paying tribute to the fallen heroes of each nation. In 1959 the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery was established to commemorate the unknown war dead. Despite various proposals, attempts to shift some or all official memorialization of the military dead—including in some instances the military dead of all countries—from Yasukuni to Chidorigafuchi have failed.

[33] Andrew M. McGreevy, Arlington National Cemetery and Yasukuni Jinja: History, Memory, and the Sacred, Japan Focus. The shrine authorities have brushed aside demands by Korean, Taiwanese and Okinawan families to disenshrine their family members, insisting that Yasukuni alone decides who is to be enshrined. Taiwanese and Koreans were drafted in the final years of the war; Okinawan youth were mobilized for “volunteer corps” as nurses or fighters to support Japanese forces during the battle.

[34] “Japanese Racism, War, and the POW Experience,” in Mark Selden and Alvin So eds., War and State Terrorism. The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004) pp. 119-42. David McNeill, Magnificent Obsession: Japan’s Bone Man and the World War II Dead in the Pacific, Japan Focus. The British and the Americans chose different routes to honoring the dead in World War I, the British maintaining cemeteries in France which consecrated more than one million Britons who died in the war (approximately half of whom were unidentified or whose bodies had vanished). As a result, the Cenotaph in London became the primary British memorial. The American government, too, made efforts to keep the dead in cemeteries in France, Belgium and England, In the end, however, more than 70 percent were repatriated, with Congress financing round-trip tickets to Europe to visit the cemeteries for mothers of the deceased. Thomas W. Laqueur, “Memory and Naming in the Great War,” and G. Kurt Piehler, “The War Dead and the Gold Star: American Commemoration of the First World War,” in John R. Gillis, ed., The Politics of National Identity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), pp. 150-67, 168-85.

[35] Japanese progressive scholars, who have written extensively and insightfully about the Yasukuni problem, rarely write comparatively about Japan’s war nationalism, atrocities, or other aspects of US and Japanese wars. An important exception is Tanaka Toshiyuki, Sora no sensoshi (History of Air War) (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2008); see also his Hidden Horrors. Japanese War Crimes in World War II (Boulder: Westview, 1996).

[36] “The Goodness of Nations,” in the Spectre of Comparisons. Nationalism, Southeast Asia and the World (Verso: London, 1998), p. 368.

[37] We have noted one important difference in Okinawa’s Cornerstone of Peace from other memorials: its commemoration of victims of all nations. There is another important difference. Exhibits in the Okinawan Prefectual Museum at Mabumi contain extensive information which reveals Japanese treatment of Okinawan civilians such as the military’s impositin of compulsory mass suicide (shudan jiketsu). The contrast to both the Yushukan and the Smithsonian Museum’s Enola Gay exhibit on the fiftieth Anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could not be starker. See Gerald Figal, “Waging Peace on Okinawa,” in Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds., Islands of Discontent. Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), pp. 65-98; Laura Hein and Mark Selden, “Commemoration and Silence: Fifty Years of Remembering the Bomb in America and Japan,” in Hein and Selden, eds., Living With the bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), pp.3-36.

[38] The US does prosecute a small fraction of its own war crimes, in each case singling out a soldier or soldiers who committed specific atrocities without examining the pattern of warfare of which it was a part, or pursuing the issue up the chain of command as required by the Nuremberg principles.

[39] Mark Selden, Japanese and American War Atrocities, Historical Memory and Reconciliation: World War II to Today.

[40] Chalmers Johnson, The Sorrows of Empire. Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004) is the classic study of the US empire of bases. See especially pp. 151-86.

[41] On the historical periodization of East Asian region formation, see Giovanni Arrighi, Takeshi Hamashita and Mark Selden, eds., The Resurgence of East Asia: 500, 150 and 50 Year Perspectives (London: Routledge, 2003) and Takeshi Hamashita, China, East Asia and the Global Economy: Regional and Historical Perspectives (Linda Grove and Mark Selden, eds.) (Routledge: London, 2008).

[42] Peter J. Katzenstein, A World of Regions: Asia and Europe in the American Imperium (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005).