The Aso Mining Company in World War II: History and

By William Underwood

Despite his recently failed third attempt to become prime minister, Aso Taro remains one of

Japan the Tremendous, a bestseller written in a populist tone, highlights the peaceful nature of postwar

Aso Taro:

But a 1975 book called The 100-Year History of Aso sends a different message about the would-be prime minister’s view of World War II and his vision for

Aso Taro oversaw publication of the 1,500-page company history as president and CEO of Aso Cement Co. Marking the centennial of the family firm, the book suggests the

The World War II chapter of The 100-Year History of Aso begins by recapping the Imperial Japanese Army’s move into Manchuria in 1931, followed in 1932 by the spread of war to

Aso Takakichi, Aso Taro’s father, became the second president of Aso Mining Co. in 1934 at age 24. Aso Taro’s great-grandfather founded the business in 1872, supplying “black diamonds” from the Kyushu coalfields to fuel

Aso Takakichi forged his own identity as the new boss by establishing

In a section called “Aso Fights,” the corporate history quotes for several pages the January 1940 address to assembled employees by Aso Takakichi, whose son Taro would be born later that year. Aso sought to motivate the miners by portraying the firm as a front-line unit in

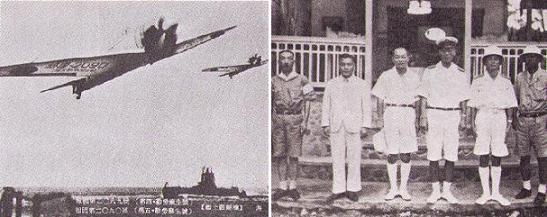

Aso Takakichi, left, took charge of Aso Mining in the 1930s,

while Aso Taro was running the family firm when the corporate

history was published in 1975. (The 100-Year History of Aso)

“In our country labor and management are one, facing in the same direction—toward the emperor. We must advance on the path of national duty,” Aso solemnly told his workforce, stressing the sacred nature of coal mining and the urgent need for greater self-sacrifice. “If it is possible that anyone here does not understand this spirit of service to the nation, as a Japanese subject he should be truly ashamed.”

Aso Takakichi struck an anti-capitalist chord by insisting that the corporation’s goal was not to make money. He told the employees that while some profit was required to fulfill his duty of continuing the family business, additional profits would be gladly distributed to workers first. He pledged to reward workers by building facilities for their benefit and helping to improve public services.

Noting that 1940 was the 2,600th anniversary of

“Whether we liked it or not and even as the world busily tried to avert war,” the Aso chronicle states, “the unfortunate year of Showa sixteen (1941) was just like a pus-filled tumor that resists medical treatment and bursts open. Charging into an economic war to secure natural resources became unavoidable.”

Top

“This cleverly united American opinion for war against

Aso Mining responded to this “most desperate crisis in Japanese history” by digging coal in record quantities. The company became like a “kamikaze special attack production unit.”

“Coal is the mother of greater military strength,” wartime Prime Minister Tojo Hideki is quoted as saying. Given

“In response to the enemy’s materiel offensive, we will fight by means of increased coal production,” said Kishi Nobusuke, then

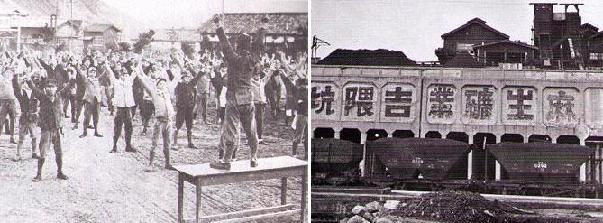

Left: Aso miners doing calisthenics during the war; right: ore cars

at the Aso Yoshikuma mine. (The 100-Year History of Aso)

Tojo was executed as a Class A war criminal in 1948. Kishi was imprisoned for three years as a Class A war crimes suspect but never tried. He served as Japanese prime minister from 1957 to 1960, and was a main founder of the LDP. Abe Shinzo, whose rocky year as prime minister ended in September, is Kishi’s grandson.

Aso Taro’s grandfather was Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, the most powerful Japanese leader of the occupation era, while his wife is the daughter of former Prime Minister Suzuki Zenko. Aso’s sister is married to Prince Tomohito of Mikasa, a first cousin of the current emperor. His great-great-grandfather, Okubo Toshimichi, was a chief architect of the modern Japanese state. Aso’s family lineage thus runs from the upper echelons of the Meiji Restoration through postwar

The 1975 book recalls wartime initiatives like the “Certain Decisive Victory Increased Production Campaign.” Government slogans included “Planes, ships and bullets: all thanks to coal,” and “One lump of coal equals one drop of blood.”

Weekends disappeared during the move to a seven-day workweek, jokingly replaced by two Mondays and two Fridays. But coal production eventually plunged as skilled miners became soldiers and shipped out for overseas battlefields. The lack of mining materials and equipment during the desperate late-war years led to reckless mining and ruined mines.

Aso Mining and Forced Labor

Severe manpower shortages necessitated the widespread use of forced labor in wartime

Aso Mining was employing 7,996 Korean conscripts as of January 1944, according to a wartime report by the Special Higher Police (Tokubetsu Koto Keisatsu), and 56 conscripts had recently died. Fukuoka-based historians estimate Aso used a total of 12,000 Koreans between 1939 and 1945. The wartime police report shows that 61.5 percent of Aso’s Korean laborers resisted conscription by fleeing their work sites, the highest percentage of runaways in the region. While this figure indicates that security conditions were not prison-like, most Korean conscripts in

Young Korean labor conscripts at Aso Mining’s Atago mine:

workers assigned to the Jowa dormitory in 1942 (top) and

the Yamato dormitory in 1943. (Hayashi Eidai photos)

There were also 300 Allied POWs at the Aso Yoshikuma mine in

Yet the family conglomerate, now known as Aso Group and headed by Aso Taro’s younger brother, has never publicly acknowledged or commented on its POW legacy. Recent phone calls to the

A spokesperson for then-Foreign Minister Aso addressed the POW issue for the first time in June 2007, but stopped short of acknowledging the historical record (see article below). Previously, the Foreign Ministry had cast doubt on foreign media reports about the Aso-POW connection. Japanese-language media have avoided reporting the issue.

The 1,500-page Aso corporate history contains a single cryptic reference to wartime forced labor. As Japanese miners left for military service, the book says, “people like Korean laborers and Chinese prisoners of war filled the void” in

Although 6,090 Chinese forced laborers were used at 16 sites in

The

Shortly after Aso Taro became foreign minister in late 2005, a South Korean truth commission official charged that Japanese companies were not cooperating in efforts to locate the remains of Korean workers still in

“The corporations’ survey of remains has been insincere,” the South Korean official said. “It is also strange that the family company of the foreign minister, who should be setting an example, has provided no information whatsoever.”[2]

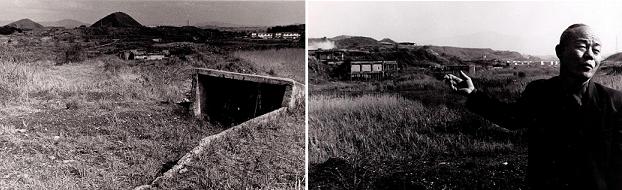

Aso Mining’s former Akasaka mine in the late 1970s and

a Korean forced to work there during World War II. (Hayashi Eidai photos)

Aso Group today consists of more than 60 companies in diverse fields such as health care, education, construction and real estate, while also supplying gasoline and running a golf course located beside the former Yoshikuma mine. Aso Cement merged with Lafarge, the French multinational and world’s largest cement maker, in 2001. Aso ceased coal mining in the 1960s.

Highlighting the company motto, “We deliver the best,” the flashy Aso Group website plays up the family’s Meiji-era business roots and provides excerpts from The 100-Year History of Aso. Yet wartime records related to Aso’s use of forced labor have apparently vanished.

“We couldn’t investigate into the history of Aso Mining even if we wanted to, because records just aren’t available from so long ago,” an Aso Group official told the Associated Press in November 2005. “All we can say is that everybody employed forced labour during the war. There must have been a dozen mining companies in

Disappearing Korean Remains

In February 2006 the Japanese Foreign Ministry (headed by Aso Taro) was informed by Aso Group (headed by Aso Yutaka) that Aso Cement had returned six sets of Korean remains to family members living in the vicinity of the Aso Yoshikuma coal mine in 1984-85.[4]

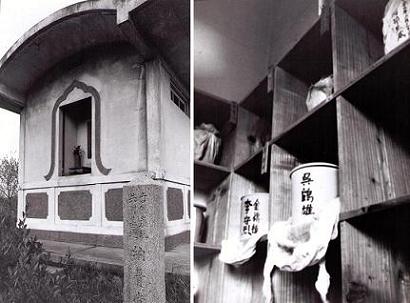

During redevelopment in the 1960s, a communal cemetery containing the cremated remains of an estimated 504 people was discovered near the entrance to the recently closed Yoshikuma mine. Aso Mining soon built a charnel house a few hundred meters from the cemetery and transferred the remains into it.

In the early 1970s, Zainichi Korean and Japanese activists began researching the

Hayashi gained access to the Aso-built charnel house in 1975 and photographed six remains containers (known as tsubo), each of them bearing a Korean name. The rest of the remains were either unidentified or belonged to working-class Japanese with no known next of kin. Hayashi returned to the Yoshikuma charnel house the following year to gather information for a television documentary.

By 1976, however, all six sets of Korean remains had been removed from the charnel house shelves. Hayashi was shown a small hole beneath the shelves and told by the Buddhist priest in charge that the Korean remains had been deposited in an underground storage area. The unusual funerary practice was not further explained.

1975 images of the exterior and interior of the Aso Yoshikuma charnel house.

Six containers of Korean ashes (right) disappeared the following year. (Hayashi Eidai photos)

Aso Taro was president of Aso Cement at the time; he left the post upon his election to the House of Representatives in 1979. Korean conscript remains may have been removed from the shelves of the Aso Yoshikuma charnel house in 1975-76 because they were viewed as a potential liability for the family scion’s political career.

Today, Hayashi and other Fukuoka-based researchers doubt the veracity of Aso Group’s claim that the six sets of Korean remains were returned to family members.

Instead, the

It is also unclear why Aso Cement supposedly handed over the ashes at that time: four decades after the war’s end, two decades after the remains were exhumed from the cemetery at the Yoshikuma site, and one decade after they disappeared from the charnel house shelves following the first researcher inquiries.[5]

The World War II chapter of the Aso history book concludes by describing the company’s late-war mining venture on the

Photographs in the book depict Aso workers doing calisthenics before entering the

Left: Imperial Navy warplanes; right: Aso Mining officials in the

(The 100-Year History of Aso)

It is not surprising that an account of Aso Mining’s wartime activities includes the imperial ideology and spiritual mobilization so central to the period. It is also true that the Aso dynasty has made many positive contributions to the

Yet the book’s silence about the company’s own use of forced labor, and the suggestion that

Aso has infuriated Koreans by defending

The Aso company line on World War II resembles the revisionist narrative being advanced by Yasukuni’s controversial history museum, which seeks to justify

“Historical perspectives based on masochistic views don’t correspond with my philosophy,” Aso said last month during a key debate with Fukuda Yasuo, referring to how he would approach contentious war-related issues. Fukuda, who seeks to address

“Masochistic” (jigyakuteki) is a codeword used by Japanese groups, in and out of the LDP, advocating a historical perspective that

Aso left the helm of the Foreign Ministry and became LDP secretary general last August, following the party’s disastrous showing in Upper House elections in July. The new job was viewed as the ideal springboard for Aso to eventually succeed Abe Shinzo as prime minister.

Most news reports of Abe’s sudden resignation in September mentioned Aso as the probable next prime minister. LDP factions soon united around the grandfatherly Fukuda instead, but Aso still received far more party support than expected, especially from local LDP chapters. Younger Japanese are said to appreciate Aso’s unvarnished speaking style and identify with his passion for manga comic books.

Although Aso Taro, 67, held key cabinet posts in both the Abe and Koizumi administrations, he turned down Prime Minister Fukuda’s request to join the current cabinet. “I want to have my hands free,” Aso told reporters, signaling that his prime ministerial ambitions remain intact.

Despite his reputation as an assertive nationalist, Aso served as the point man for

Readers of The 100-Year History of Aso may sense a mismatch between the vision and the man who would be prime minister.

. . . . . . . . . .

Aso questions content of 1946 records

By William Underwood

Aso Taro now possesses the postwar records proving that Aso Mining used Allied POW forced labor, but his spokesperson has made conflicting statements about their meaning.

Last June, I mailed the then-foreign minister both Japanese and English versions of the Aso Company Report, produced by his family’s firm on Jan. 24, 1946. Ordered by Occupation authorities investigating war crimes against Allied prisoners, the report clearly shows that 300 POWs were assigned to the Aso Yoshikuma coal mine.

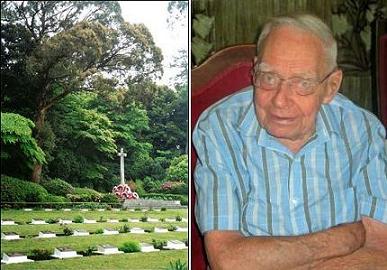

Ex-POW Arthur Gigger was forced to work without pay for Aso Mining in 1945

(Ian Millard photo). Two of Gigger’s fellow Australians died at the Yoshikuma mine

and are buried in the

Muramatsu Ichiro, Aso’s policy secretary, was then interviewed by telephone twice. “The authenticity of the documents is very high,” he said during a freewheeling, hour-long conversation on June 21. The report is written on company stationery and bears an official seal.

Muramatsu seemed to readily agree that the Australian, British and Dutch prisoners had dug coal for Aso Mining beginning in May 1945. But he questioned whether their work could be described as “forced labor,” stressing that the Aso Company Report says wages were paid. Australian survivors of the Yoshikuma labor camp, however, have insisted they received no money from Aso.

“How was a POW any different from a conscripted Japanese worker?” Muramatsu asked.

He also raised the subject of Japanese POWs who were taken to Siberia by the

The compensation fund for Nazi-era forced labor set up by

Muramatsu also said that Aso Mining Co. had no connection to Aso Cement Co., which was headed by Aso Taro during most of the 1970s. But the Aso Group website today proudly highlights the historical continuity of the family’s various businesses.

The abandoned Aso Yoshikuma work office (left) and ruined Yoshikuma mine

buildings in the late 1970s. (Hayashi Eidai photos)

A shorter, less cordial phone call to Aso’s policy secretary took place on June 22. I asked Muramatsu to clarify whether the Allied prisoners performed “forced labor” at Yoshikuma and why they do not appear in The 100-Year History of Aso.

Muramatsu then reversed his previous position, refusing to acknowledge that Aso Mining used Allied POWs at all.

He said the contents of the 1946 Aso Company Report should be accepted or rejected in their entirety. With American war crimes investigators as its target audience, the report claims the Western prisoners were treated better than Japanese workers and thanked Aso Mining staff by giving them gifts after the war.

“Selectively using the records is dishonest,” Muramatsu said.

William Underwood, a faculty member at Kurume Institute of Technology and a Japan Focus coordinator, completed his doctoral dissertation at

This is an expanded and updated version of an article that originally appeared in the

See also related articles by William Underwood:

Proof of POW Forced Labor for Japan’s Foreign Minister: The Aso Mines

Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages (1): Reparations for Korean Forced Labor in Japan

Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages (2): Seeking Redress for Korean Forced Labor

Endnotes

[1] Aso Hyakunen Shi. Iizuka,

[2] “Aso gaisho no kankei kaisha, choyosha ikotsu joho teikyo sezu, Kankoku de hihan.” Yomiuri Shimbun online (

[3] “Japan FM family firm in spotlight.” BBC News online. Nov. 30, 2005. Available. It should be noted that the Aso spokesman likely used the term “choyo” (best translated as labor “conscription”), not “kyosei renko” (best translated as “forced labor”).

[4] “Aso gaisho no shinzoku kigyo, tanko shikichinai no Chosenjin ikotsu 6 tai wo henkan.” Yomiuri Shimbun online (

[5] This account of Korean remains at the Aso Yoshikuma charnel house (Japanese version here) is based on an unpublished manuscript, “Human Remains at the Aso Yoshikuma Coal Mine,” received from Hayashi Eidai in July 2006 and follow-up conversations with him. Hayashi prepared the manuscript for possible use by a Japanese Diet member during an interpellation session, but the issue has never been raised in the Diet.