M K Bhadrakumar

Foreign ministers are busy people – especially energetic, creative diplomats like Russia’s Sergei Lavrov and Iran’s Manouchehr Mottaki, representing capitals that by tradition place great store on international diplomacy.

Therefore, the very fact that Lavrov and Mottaki have met no less than four times in as many months suggests a great deal about the high importance attached by the two capitals to their mutual understanding at the bilateral and regional level.

Moscow and Tehran have worked hard in recent months to successfully put behind them their squabble over the construction schedule of the Bushehr nuclear power plant in Iran. The first consignment of nuclear fuel for Bushehr from Russia under the International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards finally arrived in Tehran on Monday. “We have agreed with our Iranian colleagues a timeframe for completing the plant and we will make an announcement at the end of December,” said Sergei Shmatko, president of Atomstroiexport, which is building Bushehr.

At a minimum, the gateway opens for Russia’s deeper involvement in Iran’s ambitious program for civil nuclear energy. But nuclear energy is not the be-all and end-all of Russo-Iranian cooperation. Iran is a crucially important interlocutor for Russia in the field of energy. The Bushehr settlement is a necessary prerequisite if the trust and mutual confidence essential for fuller Russo-Iranian cooperation is to become reality. Evidently, Moscow is hastily positioning itself for the big event on the energy scene in 2008 – Iran’s entry as a gas-exporting country.

Russia consolidates in 2007

In fact, how Moscow proceeds with the reconfiguration of Russo-Iranian relations could well form the centerpiece of the geopolitics of energy security in Eurasia during 2008. The dynamics on this front will doubtless play out on a vast theater stretching well beyond the Eurasian space, all the way to China and Japan in the east and to the very heart of Europe in the west where the Rhine River flows.

What places Russia in an early lead in the upcoming scramble is its fantastic win in the Eurasian energy sweepstakes in 2007. But 2007 as such began on an acrimonious note for Moscow when two minutes before the clock struck midnight on December 31, Russia signed a gas deal with Belarus whereby the latter would have to pay for Russian gas supplies at full market prices on a graduated scale stretched over the next five-year period. President Vladimir Putin’s critics seized the moment with alacrity to portray him as a whimsical megalomaniac.

Moscow-based critic Pavel Felgenhauer rushed to condemn Putin’s “highly aggressive, unscrupulous and revengeful” mindset as a dictator, and prophesied that the “pressure on Belarus will most likely misfire … This may undermine the Kremlin’s authority … and provoke internal high-level acrimony [within the Kremlin]”. Other Western critics warned European countries not to count on Russia’s dependability as an energy supplier.

Much of the vicious criticism might seem in retrospect to be either prejudiced and self-interested, or downright laughable, but that didn’t prevent the acrimony from setting the tone for the geopolitics of energy during 2007. Prima facie, Russia was making a transition to market prices for its energy exports, which was quite the proper thing to do if it were to integrate with the world economy in a manner consistent with the broad orientations of its liberal economic policies.

Indeed, the Kremlin had no reason to continue with the Soviet-era subsidies to former Soviet republics like the Ukraine or Belarus. Efficiency demanded that Russia allowed market forces to prevail. Actually, that was also the capitalist world’s advice to the Kremlin.

What incensed Western critics was that combined with the state control of oil and gas (and indeed the pipelines), the Kremlin was also maneuvering its way to a commanding position on the energy map of Europe. From its own viewpoint, Russia could claim it was merely pursuing a coordinated strategy aimed at integrating itself with European economies.

But the United States viewed the implications of the Russian strategy to be very severe for trans-Atlantic relations on the whole, as it cast a shadow on the entire range of goals, strategic objectives and security policies that Washington has been pushing within the framework of the Euro-Atlantic alliance in the post-Cold War years. Plainly put, Washington fears that Europe’s strategic drift may become a reality unless Russia is stopped in its tracks.

Europe’s dependence on Russian energy

After much US prodding for a coordinated European energy security policy, European Union (EU) members adopted at their spring summit in Brussels an action plan for energy security for 2007-2009, which emphasized the need to diversify Europe’s energy sources and transport routes. But the ground reality continues to be that Europe’s dependence on Russian energy supplies is growing. In 2006, Europe imported from Russia 290.8 million tonnes of oil and 130 billion cubic meters of gas.

With Europe’s energy consumption rapidly rising, its import dependency on Russia is also set to increase. Europe, which imported around 330 billion cubic meters of gas in 2005, will require an additional 200 billion cubic meters per year by 2015. And Russia has the world’s largest natural gas reserves, estimated to be 1,688 trillion cubic feet, apart from the seventh largest proven oil reserves, exceeding 70 billion barrels (while vast regions of eastern Siberia and the Arctic remain unexplored).

On the other hand, Europe’s self-sufficiency in energy is sharply declining. By 2030, the production of oil and gas is expected to decline by 73% and 59% respectively. The result is that by 2030, two-thirds of Europe’s energy requirements will have to be met through imports. In Europe’s energy mix, the dependence on oil imports by 2030 will be as high as 94% of its needs, and on natural gas as high as 84%.

As supply becomes concentrated in Russian hands, the Kremlin will find itself in a position to dictate oil and gas prices. There is also the possibility that the supply and demand situation itself might become less elastic – Russia’s own demand for gas, for instance, is growing by over 2% annually.

Clearly, the economics of energy supply to Europe are getting highly politicized. Ariel Cohen, a prominent Russia specialist at the US think-tank, Heritage Foundation, who is closely connected with the George W Bush administration, wrote recently, “It is in the US’s strategic interests to mitigate Europe’s dependence on Russian energy. The Kremlin will likely use Europe’s dependence to promote its largely anti-American foreign policy agenda. This would significantly limit the maneuvering space available to America’s European allies, forcing them to choose between an affordable and stable energy supply and siding with the US on some key issues.”

Cohen warned,

“If current trends prevail, the Kremlin could translate its energy monopoly into untenable foreign and security policy influence in Europe to the detriment of European-American relations. In particular, Russia is seeking recognition of its predominant role in the post-Soviet space and Eastern Europe … This will affect the geopolitical issues important to the US, such as NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] expansion to Ukraine and Georgia, ballistic missile defense, Kosovo, and US and European influence in the post-Soviet space.”

US-Russia rivalries escalate

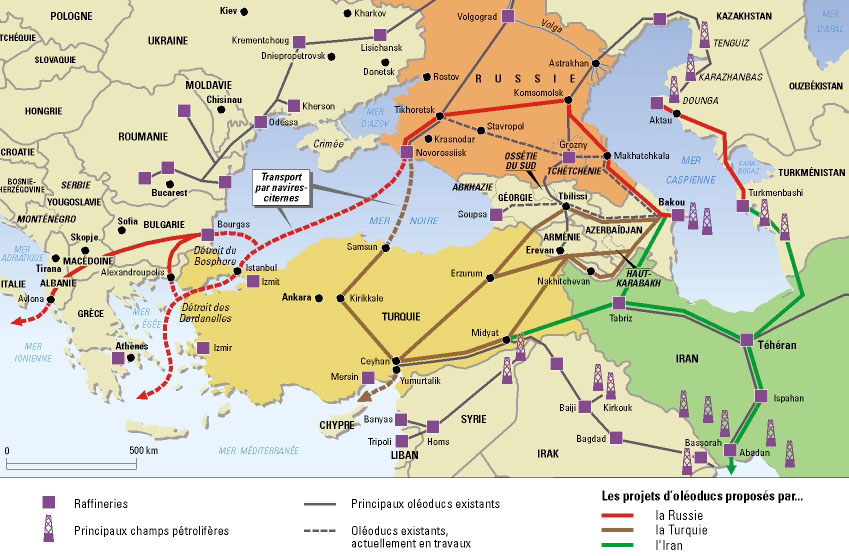

Thus, through the past 12-month period, the Bush administration has been pressing for the development of new energy transit lines from the Caspian and Central Asia that bypass Russia. Washington has robustly worked for advancing its proposals for the construction of oil and gas pipelines linking Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to Europe across the Caspian Sea; new pipelines that would connect the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline with the Baku-Erzurum gas pipeline (making Turkey an energy hub for Europe); and the so-called Nabucco pipeline that proposes to link Azerbaijan and Central Asian countries with southern European markets.

However, as the year draws to a close, it becomes clear that the Kremlin has either nipped in the bud or frustrated one way or another the various US attempts to bypass Russia’s role as the key energy supplier for Europe. Indeed, Moscow’s counter-strategy aims at augmenting even further Russia’s profile and capacity to be Europe’s dependable energy supplier and thereby forcing the European consumer countries to negotiate with Russia as a partner with shared or equal interests.

The month of May stood out as the watershed when the geopolitics of energy in Eurasia decisively turned in Russia’s favor. At a tripartite summit meeting in the city of Turkemenbashi (Turkmenistan) on May 12, Putin and his Kazakh and Turkmen counterparts signed a declaration of intent for upgrading and expanding gas pipelines from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan along the Caspian Sea coast directly to Russia. The president of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, also signed up separately on May 9 for a modernization of the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Kazakhstan-Russia pipeline. Both pipelines are components of the Soviet-era Central Asia-Center pipeline system bound for Russia. The quadripartite project essentially aims at the transportation of Turkmenistan’s gas output, which almost in its entirety would be bought up by Russia for a 25-year period.

Subsequently, the US and EU have made herculean efforts to get Ashgabat to resile from the commitment to the project with Russia, but have failed. During the past year, 16 high-level delegations from Washington visited Ashgabat in this regard. Thus, when Russian Prime Minister Viktor Zubkov finally signed the agreement relating to the Caspian littoral pipeline on December 12 with his Kazakh and Turkmen counterparts, the curtain came down on one of the grimmest struggles of the great game in the post-Soviet era. Moscow came out the winner by far, reasserting its pre-eminent position in the Caspian.

The commitment of Turkmen gas to Russia has broader implications. For one thing, the fate of the US-supported proposals for a trans-Caspian pipeline and the Nabucco pipeline depended significantly on the availability of Turkmen and Kazakh gas. Their future is now up in the air. That, in turn, means Europe is increasingly left with only one serious option for diversifying its gas imports – Iran.

In May, Putin struck a second time when he visited Vienna and in a dramatic breakthrough drew Austria into a key energy partnership, placing that country as a base for Gazprom’s future expansion into EU territory. The agreements signed in Vienna on May 23 outlined Gazprom’s plans to build a Central European gas hub and gas transit management center, the largest in continental Europe, at Baumgarten near Vienna; expansion of Gazprom’s market share in Austria; delivery of gas directly by Gazprom to Austrian consumers – for the first time in Europe; and plans to use Austria as a transit corridor for Russian gas exports aspiring to capture new EU markets.

Austria’s “defection” to the Russian camp virtually dealt a coup de grace to Washington’s strategy to cut Russia’s share of Europe’s growing need for gas. But Moscow pressed ahead. On June 25, Gazprom signed with Italy’s Eni a memorandum of understanding (which on November 22 was finalized as an agreement) on a US$5.5 billion project for building a 900-kilometer gas pipeline (“South Stream”) with an aggregate annual capacity of 30 billion cubic meters. The pipeline will run from Russia’s Beregovaya on the Black Sea to Bulgaria, where it will split, with the two branches fanning out to reach southern Italy, Greece, Austria, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary.

A Gazprom statement highlighted the deep implications of the South Stream project when it said in a studied undertone, “This is another real step in the implementation of Gazprom’s strategy to diversify routes of Russian natural gas supplies to European countries and a considerable contribution to the energy security of Europe.”

What was unfolding was indeed a spectacular string of successes by Russia, running ahead on the one hand in the transit and downstream races of the great game over Caspian energy, while running way ahead in the upstream race for Central Asian gas to feed these projects.

But that wasn’t all. It was very obvious that the Kremlin strategy was not just about energy, but kept in view the overall agenda of integrating Russian business and industry with important western European partners. Commenting on the South Stream project, The Wall Street Journal noted:

The Italian government has bucked Europe’s concerns about Gazprom, aggressively endorsing Russia as a strategic partner in energy and other areas, such as aviation. Just last week [mid-June], Italy’s Foreign Minister Massimo D’Alema, held court in Rome with Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s first deputy prime minister and also Gazprom’s chairman, to discuss cooperation on a range of sectors. An Italian airline, for example, recently announced its intention to purchase Russian commercial aircraft and an Italian defense contractor, Finmeccanica SpA, is jointly developing a fighter jet with a Russian company.

Nothing could have brought home the shift in the geopolitical templates more dramatically than the first energy summit of the Balkan countries – a region where the US consistently sought to exorcise Russia’s historical influence – at Zagreb on June 24. Putin was invited as a special guest. Addressing the summit, Putin outlined the Russian objectives in energy cooperation with Europe. He said cooperation should be based on a “balance of interests”; “equal responsibility of suppliers, transit countries and energy consumers”; “transparent and fair business relations”; and “long-term relations”. He virtually gave notice that mutuality of interests must involve Europe dismantling its discriminatory regimes directed against Russian companies in trade and investment.

The Russian daily Izvestia reported that in 2006 European governments blocked deals worth a total of $80 billion involving Russian companies. In its commentary in July, the daily noted, “The relations between the European Union and Russian investors are coming to resemble armed combat … The European Parliament maintains that foreign companies have no right to acquire Europe’s gas and electricity distribution networks. Europe is increasingly fearful about being bought up by foreigners: the prospect of Dutch consumers receiving gas and electricity bills bearing Gazprom’s logo; gas stations in Switzerland painted in LUKoil’s colors, red and black; and kitchenware in Greece marked ‘Made by Russian Aluminum’.”

Indeed, Russian strategy also correspondingly hardened. Russia presented yet another project when it proposed the construction of a Burgas-Alexandropolis oil pipeline. The proposed pipeline would start at Russia’s Novorossiysk port on the Black Sea; it would cross over to Bulgaria’s Burgas and then proceed to the Greek port of Alexandropolis. It is in essence a rival to the trans-Caspian pipeline (CPC) that Washington has been pushing for almost a decade. The capacity of the Russian pipeline will be 15 million tonnes annually in the first stage and 35 million tonnes in the second stage. The great irony is that it is a carbon copy of the CPC insofar as it is also predicated on growing volumes of Kazakh oil being extracted by Western companies.

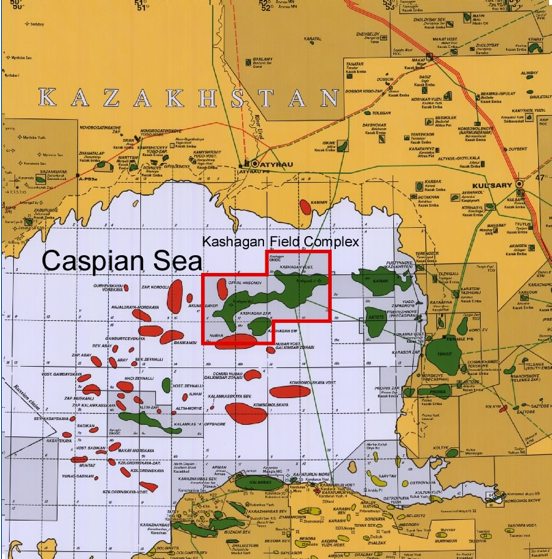

In other words, Moscow is planning that the volumes of oil coming on stream (thanks to massive investment by American oil majors Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil) in some of Kazakhstan’s richest fields (Tengiz oil field, Karachaganak oil, gas and condensate field, Kashagan oil field, etc) would be absorbed into the Russian-controlled transit route for marketing in Europe. An American specialist wrote bitterly, “This could defraud the [American] companies and their shareholders, reinforce Russia’s quasi-monopoly on the transit of oil from Kazakhstan, defeat the US-promoted east-west Caspian energy corridor, and create instead a Russian-controlled oil export axis stretching from Kazakhstan to Greece and further afield.”

Meanwhile, a struggle is shaping up for control of the Kashagan field, which is billed as the world’s largest discovery in the past 30 years. Kazakhstan wants to increase its share in Kashagan at the cost of the Western companies. The renegotiation of the Kashagan concession’s production-sharing agreement might well lead to Russia replacing some of Kazakhstan’s western partners, even though reports indicate ExxonMobil of the US is furiously lobbying to retain its stake of 18.5% as the field’s operator. The stakes are obviously high. Kashagan has proven reserves of 35 billion barrels of oil and potential reserves estimated to be as high as 70 billion barrels. When the project commences production, its daily output will be at least half a million barrels.

The Kashagan struggle highlights that the huge lead Russia has established in the past 12-month period for the control of Caspian and Central Asian energy was possible only by Russian companies investing heavily in a way that competing American oil majors would have rarely encountered in foreign operations.

The US’s last big hope in 2007 was Turkmenistan. But the December 12 agreement signals that for the foreseeable future, Ashgabat has decided on Moscow as its preferred partner for its gas exports. The deepening Russian-Turkmen ties comes as a major blow to US oil majors.

All in all, therefore, the year 2007 is ending on a sour note for Washington. In all likelihood, the US will carry forward into the New Year its sense of bitterness. Clearly, Europe is not ready to coordinate its energy strategy with the US. Former German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder recently blasted Washington’s contention that Russia is an unreliable energy partner. He said, “Experience has certainly shown that Germany has never had a problem with the supply and integrity with the energy imported into Germany from Russia, not during all of the fickle times of the Cold War, not right now, and I personally don’t see them in the future.”

Schroeder pointed out that energy rivalries lie at the core of the US policy of encirclement of Russia and behind Washington’s persistent attempts to denigrate and isolate Moscow. He warned of dire consequences if Washington persisted with such a course, as Moscow is “certainly not happy about it”.

Iran factor becomes important

In such an overall context, during the months ahead Moscow can be expected to make robust efforts to coordinate with Iran over its oil and gas output and exports. The rationale for such a coordinated strategy involving Iran is very obvious. First, Moscow is intensely conscious of the Western awareness of Iran’s enormous untapped hydrocarbon reserves as an alternative to Russian supplies. Russia will strive to stay ahead of the European, and eventually American, overtures to Iran.

Second, the hydrocarbon sector in Iran is firmly under state control and Moscow and Tehran are in harmony in this regard. Third, the two countries will be coordinating their energy policies for wider geopolitical purposes within the broad framework of their strategic cooperation. Furthermore, market forces dictate the rationale of Russia-Iran cooperation. Moscow would simply like to avoid competing with Iran, and vice versa. Russia and Iran control roughly 20% of world’s oil reserves and close to half of the world’s gas reserves, and it makes good sense to accommodate each other.

Iran is indeed an important energy partner for Russia for many reasons. Russian oil companies, flush with funds, are keen to invest abroad. The Iranian upstream oil and gas sector and Iran’s energy ventures, such as pipeline projects, offer an attractive proposition for Russian investment. Again, Iran’s geographical location is ideal as an export outlet for expanding Russian energy exports, especially its ambitious developing liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry. Besides, Iran is an influential member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, whose decisions have bearing on price stability and Russian export volumes.

But the most important consideration for Russia will be that Iran’s energy policy should not come into conflict with Russian interests. Once the US’s engagement of Iran commences, Tehran will have plenty of choice while accessing foreign capital and advanced upstream oil and gas technology. Iran is bound to probe gas markets such as Turkey, the Balkans and central and east Europe. Also, Iran is keen to develop a new LNG industry. Over and above, Iran could well end up competing with Russia as a major oil and gas route connecting the Caspian and Central Asian energy producing countries.

Cooperation with Iran is no less important for Russia in terms of Caspian Sea issues. True, the two countries have divergent views on how the Caspian Sea should be divided. Russia prefers a median line solution, whereas Iran has insisted on an equal share (20%) solution for each littoral state regardless of the length of coastline. All the same, Russia and Iran are in profound agreement in their opposition to the US-led trans-Caspian pipeline projects.

Russia’s number one priority in energy cooperation with Iran will be for upstream participation by Russian companies. Gazprom has had some limited participation so far in the early phases of Iran’s massive South Pars gas fields with an estimated aggregate cumulative production range of a stunning 13 trillion cubic meters. Moscow will be keen to promote greater involvement. Gazprom has shown interest in the Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline project not only as a contractor but also as an investor.

But the big-ticket item will be the future development phases of South Pars, which Tehran has earmarked as feedstock for producing and exporting LNG for the European and Asian markets. Without doubt, Moscow will be keen to develop a role in Iran’s nascent LNG industry so that it doesn’t end up competing with Russia’s own LNG industry.

Following his talks with Lavrov in Moscow last week, Mottaki stressed that the unfolding expansion of relations between Iran and Russia stems from a highly strategic decision taken by the leadership in Tehran. Specifically, Mottaki proposed the setting up of a joint gas company with Russia. Moscow would be favorably inclined towards the Iranian proposal, as it broadly aims at eliminating the possibility of the two countries competing with each other in the range of activities related to gas exports such as production, transportation, sales and prices.

Over and above, Moscow would be pleased at the present orientation of Iranian energy exports toward the Asian market. On the one hand, this would ease the competition from China for gaining access to Central Asian energy producers and on the other, it reduces the likelihood of Iranian energy flows to Europe, which may otherwise cut into Russia’s market share.

Equally, Russia would actively promote an Iranian gas pipeline to China via Pakistan and India. But the project is stalled due to US pressure on India. Konstantin Simonov, the chief of Russia’s National Energy Security Fund, alleged recently that by opposing the Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline, the US is principally trying to deny China easy access to Iranian energy reserves.

To be sure, Moscow began anticipating several months ago that with the inevitable collapse of the United States’ policy of containment of Iran and with Iran’s ensuing arrival as a gas exporting country, an altogether new scenario would shape up on Eurasia’s energy map. Moscow would also have taken stock of the 1979 Iranian revolution’s ideological struggle between “black Shi’ism” and “red Shi’ism”, which has, significantly enough, resumed lately. The West has always been an interested party in the outcome of this struggle.

Two former Western-oriented Iranian presidents – Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammed Khatami – have joined hands in an unlikely alliance of conservatives and liberals. A regime change in Tehran holds out the possibility that the two energy superstars – Russia and Iran – could find themselves being set against each other by the West, or end up treading on each other’s toes.

Thus, Putin’s historic visit to Tehran on October 16, the first-ever bilateral visit by a Russian leader – Tsarist or Bolshevik – falls into perspective as a landmark event in the geopolitics of energy in the coming period. On whichever turf he has so far touched on energy security, Putin has left his unique personal stamp – that of the keen anticipation of a chess player blending with his swiftness as a black belt in judo. But the Persian chessboard is no easy turf. Putin’s moves will therefore be an absorbing sight to watch. Perhaps they are destined to form yet another of his fine legacies in post-Soviet Russia’s historic transformation as a great power in the 21st century.

M K Bhadrakumar served as a career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service for over 29 years, with postings including India’s ambassador to Uzbekistan (1995-1998) and to Turkey (1998-2001).

This article appeared at Asia Times on December 22, 2007. It was posted at Japan Focus on December 23, 2007.