M K Bhadrakumar

It may seem improbable that a regional cooperation organization commences its annual summit against the backdrop of military exercises. The European Union, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the African Union, the Organization of Latin American States – none of them has ever done that.

Therefore, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is indeed making a very big point by way of holding its large-scale military exercises from August 9-17. The SCO is loudly proclaiming to the international community that there is no “vacuum” in Central Asia’s strategic space that needs to be filled by security organizations from outside the region.

The exercises, code-named “Peace Mission 2007”, will be held in Chelyabinsk in Russia’s Volga-Ural military district and in Urumqi, capital of China’s Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region. The SCO summit is scheduled to take place in the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek on August 16. After the summit, in a highly symbolic gesture, the heads of states and defense ministers of all SCO members – China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan – will watch the conclusion of the joint military exercise in Urumqi.

SCO military exercie in Kyrgyzstan

SCO military exercie in Kyrgyzstan

The SCO has never held a full-scale military exercise involving all its member states. An estimated 6,500 troops will take part in the exercise, including 2,000 Russian and 1,600 Chinese personnel. This is the first time that China will be deputing its airborne units for a military exercise abroad. Russia and China will deploy 36 and 46 aircraft respectively and will each contribute six Il-76 military transport aircraft to perform simulated airborne assaults.

A Chinese military expert, Peng Guangqian of China’s Academy of Military Sciences, was quoted by the People’s Daily as saying, “The drill mainly aims to showcase the improved security cooperation among the SCO member states, the reinforced anti-terror capability of SCO members, the improved Sino-Russian relationship and the modernization of the member countries’ armed forces.”

The government-owned China Daily underlined that the exercises show that “SCO cooperation over security has gone beyond the issues of regional disarmament and borders, for it includes how to deal with non-traditional threats such as terrorists, secessionist forces and extremist religious groups”.

Map showing SCO military exercises centered on Xinjiang

Map showing SCO military exercises centered on Xinjiang

The Chinese Ministry of Defense in a statement stressed that the exercises “do not target other countries and do not involve interests of countries outside the SCO”. Briefing the media, the deputy commander of Russia’s ground forces, General Vladimir Moltenskoi, also said the exercises were “not aimed at third countries”.

CSTO embraces China

Despite these understatements, it is all too obvious that Sino-Russian strategic cooperation is reaching a qualitatively new level. The most important indicator in this direction is that the summit at Bishkek may witness the signing of a formal protocol of cooperation between the SCO and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). The document is expected to define clearly the cooperation trends between the two regional security organizations in the coming period.

This is undoubtedly a major development in the Eurasian strategic space. The proposed formal link between the CSTO and the SCO in essence involves the CSTO plus China, as the SCO member countries other than China are already members of the CSTO. (The CSTO member countries are Russia, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.)

It cannot be lost on anyone that the CSTO-SCO partnership is being formalized hardly a month after Moscow’s decision on July 14 to suspend its participation in the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE). The CFE was the first-ever post-World War II conventional arms reduction treaty reached between the East and the West.

Influential Russian strategic analyst Gleb Pavlovsky warned on July 14, “Today’s decision is not propaganda, it is a transition to a new serious phase in Russia’s construction of a new security architecture against the background of the world’s rearmament near our borders.”

Referring to the relentless US encirclement of Russia, he added, “Virtually all countries along Russia’s southern and western borders are being stuffed with missiles … A mad arms race in the Caucasus, Caspian and Black Sea regions is under way, and it is being maintained by European and non-European countries, none of them restricted by the CFE.”

In this context, Pavlovsky said, Moscow will opt preferably for “new contractual balances” in Europe and Asia. “If the countries of Europe and Asia are prepared for this, Russia will be the first to agree to such negotiations.”

We may be seeing in the CSTO-SCO institutional linkup the first evidence of the “new contractual balances” that Pavlovsky mentioned. The Russian thinking in the direction of building up the CSTO’s sinews as a counterweight to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has been evident for some months.

Last December, addressing a Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Baltic States media forum, Deputy Prime Minister (concurrently Russia’s defense minister at that time) Sergei Ivanov said, “The next logical thing on the path of reinforcing international security may be to develop a cooperation mechanism between NATO and CSTO, followed by a clear division of spheres of responsibility. This approach offers the prospect of enabling us to possess sufficiently reliable and effective leverage for taking joint action in crisis situations in various regions of the world.” (Emphasis added.)

Not that Ivanov was unaware that NATO was not in the least interested in dealing with the CSTO. (The CSTO countries cover roughly 70% of the territory of the former Soviet Union.) For the past three years, Russia has been proposing the desirability of limited cooperation between the CSTO and NATO in countering drug trafficking originating in Afghanistan. But NATO, at Washington’s bidding, has been stalling. It has been NATO’s (and Washington’s) consistent policy not to recognize the CSTO’s standing as a regional security organization, and to deal instead with the CSTO member countries on a bilateral basis.

Therefore, what Ivanov was stressing is that Moscow will be every bit determined to resist NATO’s encroachment into the territories of the former Soviet republics. This emanated out of Moscow’s assessment that NATO will not be averse to expanding even further, by offering membership to some CIS countries. Russia is opposed to such expansion, but its diplomatic efforts are not working. The military option has become necessary. In his speech, Ivanov not only made a resolute statement about the CSTO’s place in Europe but also hinted that Moscow views the Central Asian countries in the SCO, especially China, as its potential bloc allies.

A few months later, in May, while speaking at a conference in Bishkek on 21st-century security threats and challenges, CSTO secretary general Nikolai Bordyuzha frontally attacked NATO, saying it pursues “a policy of projecting and consolidating its military-political presence in the Caucasus and in Central Asia”. He added that these activities pose “challenges and risks” and undermine stability in the post-Soviet space.

Bordyuzha elaborated that the United States’ Central Asia strategy aims at driving a “geopolitical wedge” between regional states on the one hand and Russia and the CSTO on the other. He said Washington is attempting to reorient the Central Asian states toward the US “in a new format encompassing, besides the Central Asian states, Afghanistan, Pakistan and, in the future, India”.

Indeed, recently Russia has all but blunted NATO’s Central Asia strategy. In retrospect, NATO underestimated its capacity to gatecrash into a region where Russia’s traditional influence is overwhelming and where Moscow is determined to keep things that way no matter what it takes.

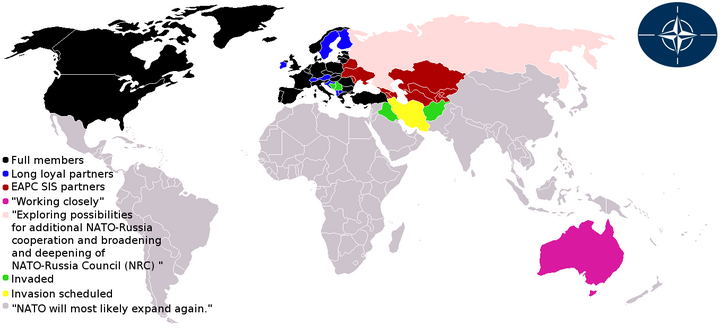

NATO members and partners, 2006

NATO members and partners, 2006

Over the past two years, Moscow has rapidly built up the CSTO as a bulwark against NATO in Central Asia. Some Russian commentators have forecast that the CSTO is destined to become a Warsaw Pact. Be that as it may, almost in direct proportion to Moscow’s emphasis on the CSTO, there has been a rallying by the Central Asian countries under the CSTO, especially by Kazakhstan, which was a prime “target” identified by NATO. Uzbekistan’s entry into the CSTO has significantly consolidated the reach of the organization over the Central Asian region.

Sino-Russian convergence

Clearly, China appreciates that the contradictions and struggles between Russia and Western powers in the post-Cold War years are at a defining moment. Writing in the People’s Daily recently, Wang Baofu, deputy director of the Institute of Strategic Studies affiliated to the elite Chinese National Defense University, said, “This move of Russia’s [suspension of the CFE] indicated firstly its reluctance to make any additional unilateral compromises on the major issue of national security … and, secondly, its unwillingness to sit idle and remain indifferent as the US is attempting to deploy an anti-missile system in Eastern Europe in a bid to seriously affect the Russia-US strategic balance.”

Wang noted that Russia’s security concerns are bound to multiply in the prevailing scenario of “disequilibrium”, where the US is “bent on seizing or using Europe to beef up its strategic superiority over Russia”. Again, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman on July 19 “took note of Russia’s statement [on the CFE] and its security concern”. The spokesman added that the US deployment of its anti-ballistic-missile system will “undermine the current international strategic balance and stability. It is not conducive to regional security and mutual trust between countries.”

Meanwhile, Chinese commentators have estimated that “Russia lately seems to be toughening up its diplomatic posture” and is “hardening its attitude” toward the West. The bottom line in the various Chinese assessments is that Moscow’s “hard-nosed stance” aims at putting Russia on an equal footing with Western powers.

All the same, in relation to Central Asia (and Afghanistan), China has shared concerns with Russia, especially on two aspects. First, China also harbors misgivings about NATO’s designs toward Central Asia. China remains appreciative of Russian efforts to keep NATO out of Central Asia. To quote a recent People’s Daily commentary, “Knowing by heart the strategic importance of Central Asia, NATO has spared no efforts in recent years to push forward relations with the countries in this region. But it is by no means an easy job for NATO to gain a footing, given the overwhelming traditional influence of Russia in this region, which the US and Europe can never hope to equal.

“By focusing on hammering out the CSTO, Russia has displayed a strong sense of opposition against NATO. Now, the low relations between Russia and NATO have added difficulty to the latter’s implementation of its Central Asia strategy.”

China’s interests coincide with the Russian approach of bolstering the CSTO’s reach in Central Asia. The CSTO-SCO nexus reinforces Russian efforts in “containing” NATO to the southwestern fringes of Eurasia. Chinese interests are well served by these Russian efforts.

Second, it is becoming increasingly evident that both Russia and China have been thinking hard on the concept of Central Asia. The point is, it is unrealistic for Russia and China (and for the SCO) to deal with the processes that are going on in the Central Asian region without taking into consideration the developments in Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. As a Russian commentator recently wrote in Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Central Asia’s southern neighbors (Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan) hold “much greater significance for Tajikistan than the squabbling within Kazakhstan’s elite”.

Arguably, the SCO is feeling the compulsion already to visualize that Central Asia as a distinct community has more to do with history – its ancient, medieval and Soviet history – than with pressing contemporary realities. The SCO has to come to terms with the reality that even though Central and South Asia used to belong to different geopolitical templates until quite recently, this is no longer so, especially after September 11, 2001, provided the US the opportunity to establish a long-term presence in Afghanistan and to gain a significant leap in its relations with the Central Asian states.

After consolidating its presence in Afghanistan, US policy toward Central Asia has shifted gears. Through different, flexible modes of cooperation in the fields of security, transportation and energy as well as through continued efforts to bring about “regime change” in the region, the US hopes to remodel the region.

Meanwhile, the continuous expansion of US influence in South Asia has come handy in this effort, as Afghanistan is a vital link that can connect Central Asia with South Asia. Washington has of late taken greater interest in South Asian regional cooperation by seeking observer status in SAARC, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation that includes India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Maldives, Bhutan and Afghanistan. It would seem that Washington has met with some degree of success already in persuading India to cool down its earlier passion toward the SCO.

Iran seeks out SCO

The SCO is increasingly bound to feel the need to evolve its own “Greater Central Asia” strategy, which also includes Iran and Afghanistan, and to some extent even Pakistan.

This may already be happening, and may be reflected in different directions at the SCO summit in Bishkek. First, Iran is making a determined bid to secure full membership of the SCO. Tehran submitted its formal application to the host country Kyrgyzstan in April. In the usual course, such a formal move would have taken place on the basis of prior consultations with the SCO member states. Conceivably, a consensus is slowly developing within the SCO, if not already, on the issue of Iran’s membership.

Significantly, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Mahdi Safari last week revealed that President Mahmud Ahmadinejad would attend the SCO summit. Safari has since visited Beijing, where he met, among others, with Li Hui, China’s deputy foreign minister in charge of East Europe, Central Asia and the SCO.

From Beijing, Safari headed for Moscow. Admittedly, Russian-Iranian relations are currently going through a rough patch over Russia’s delay in completing the Bushehr nuclear power plant in Iran. Indeed, Russia has “politicized” the issue and is unlikely to dispatch nuclear fuel for Bushehr as long as the Iran nuclear file remains open. Despite the chill in Russian-US relations, Washington and Moscow have always closed ranks on issues affecting the preservation of the “nuclear club”.

The main building of the Bushehr nuclear power plant (2003)

The main building of the Bushehr nuclear power plant (2003)

Besides, Russia has a great deal to gain by exploiting the agreement on civil nuclear cooperation with the US, signed on the sidelines of the “lobster summit” between Presidents George W Bush and Vladimir Putin on July 2, which is a major concession by Washington, allowing Russia to set up facilities for reprocessing spent nuclear fuel of US origin on commercial terms – a highly lucrative business indeed. In immediate terms, Washington’s concession has opened the way for Russia to reprocess the spent fuel of US origin from South Korea and Taiwan.

But at the same time, the fracas over Bushehr in a curious way gives Russia the handle to stall any further move by the US in the United Nations Security Council to push for a new sanctions resolution against Iran for not stopping its uranium-enrichment program. Moscow-based commentators have highlighted the current visit by International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors to the Arak heavy-water plant in Iran as a “real breakthrough” and as evidence that “Iranians are ready to give the IAEA exhaustive answers”.

Arak heavy-water plant in 2005 satellite image

Arak heavy-water plant in 2005 satellite image

Evidently, Bushehr is not the sum total of Russia-Iran relations. Both countries are pragmatic enough to realize that. Indeed, both countries are under compulsion to control any damage to their bilateral cooperation. Russia has shared interests with Iran in the Caspian and Central Asia. Iran is the only Caspian power, arguably, with which Russia has total identity of views as regards the inadmissibility of involvement by extra-regional powers (read the US and NATO) on issues of the security of the Caspian region. Russia has to work closely with Iran at the summit of the Caspian littoral states scheduled to take place in Tehran this year.

The CSTO’s Bordyuzha might have spoken with a swagger when he recently invited Iran to join the CSTO as a member country. But the proposition wasn’t entirely lacking in seriousness. During the visit of Kyrgyz Foreign Minister Kadyrbek Sarbayev to Tehran on July 15, the influential chairman of the Security and Foreign Policy Committee of the Iranian Majlis (parliament), Ala’eddin Broujerdi, strongly criticized the intrusive regional policies of the US in Central Asia.

He roundly condemned the US for plotting to destabilize the Central Asian region. Interestingly, Broujerdi called for the exclusion of extra-regional security organizations from Central Asia. Broujerdi’s stance on Central Asian security was almost the same as that of Russia and China.

A key agenda item to be watched at the SCO’s Bishkek summit will be the role of Iran in energy cooperation. This is a topic of common interest to Russia and China. On its part, Russia stands to gain if Iran’s energy flows are diverted toward the Asian market rather than finding their way to the European market. (Safari has been quoted as saying in Beijing on August 6, “Iran is willing to draw up an energy charter to cover the entire Asia.”)

Russia has been watching with unease the renewed efforts by Turkey and the European Union (despite apparent US reservations) to line up Iran both as a gas supplier and as a conduit for Turkmen gas for filling up the proposed Nabucco pipeline, which rivals Russia’s energy projects in the Balkans and southern Europe. Last month, Turkey and Iran signed a memorandum of understanding in this respect. Last week, Turkey followed up with an agreement with Italy and Greece, which will be the consumers of the Iranian gas.

Russia is keenly watching, and will hope that Iran does not commit to the Nabucco pipeline. Russia has an added interest in encouraging Iran to become an energy supplier for China insofar as by doing this the potential for any Russian-Chinese conflict of interests over Central Asian energy reserves (especially in Turkmenistan) diminishes. In fact, the proposed Chinese gas pipeline leading to Turkmenistan can be easily extended to Iran. Finally, Iran is an important player in any grand Russian strategy involving a variant of the idea of a world gas cartel.

SCO’s Afghan challenge

From all these perspectives, the time has come for the SCO to ponder seriously its future relations with Iran. Without doubt, two big questions await the SCO summit: Iran’s admission as a full member and the direction of the SCO’s partnership with Turkmenistan.

Parallel to the SCO’s “Great Central Asia” strategy involving Iran, the summit can be expected to come up with new initiatives toward Afghanistan. Again, both Russia and China view with growing concern the deepening crisis in that country.

To quote from a People’s Daily commentary in June, “The ‘Taliban phenomenon’ has produced grave concern … its resurgence has severely challenged the authority of the Afghan government … the Taliban have grown more robust … taking full advantage of local feelings of dissatisfaction over living conditions and anti-US sentiments … the Taliban have galvanized their link-up with al-Qaeda remnants … Afghanistan is at risk of becoming the second Iraq.”

Russian thinking has also been on a similar track. In fact, Moscow has gone a step further and openly questioned the continued rationale of the United States’ monopoly over conflict resolution in Afghanistan. Moscow, like Beijing, is keen to adopt a two-track approach. First, it will endeavor to work closely on a bilateral track with the government headed by President Hamid Karzai. The visit by Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to Kabul signified an intensification of Russian diplomacy toward the Afghan problem. At the same time, Moscow is also looking for a multilateral approach involving the CSTO.

Significantly, Bordyuzha suggested this week, “We [CSTO and the SCO] together should assist in preventing the Taliban from coming to power, otherwise we will get serious problems in Afghanistan, problems for many years.”

Bordyuzha hinted at the likelihood of an extensive involvement by the SCO in Afghanistan. He said, “Work should be conducted in all spheres, political and economic, and in rendering assistance in the formation of armed forces and law-enforcement organs of the government, as well as in the fight against illegal drug trafficking.”

To be sure, the SCO summit can be expected to come up with proposals aimed at intensifying the functioning of the SCO-Afghanistan Contact Group.

American headaches

The SCO summit therefore poses challenges for the US from various angles. The coming together of the CSTO and the SCO is a double setback to US regional policies. Both are entities that are anathema to the United States’ geopolitical interests. The US strove to stifle these two organizations in their infancy, but instead now sees them gather new strength.

The US game plan projecting NATO into the Central Asian region runs into a formidable obstacle. The US dilemma is acute. Unless NATO expands into Central Asia, there can be no full “encirclement” of either Russia or China. It is senseless if NATO remains stuck in the southern Caucasus.

Indeed, NATO’s credibility is at stake, too. As things stand, NATO’s “transformation” isn’t progressing smoothly. Afghanistan has become a lump in NATO’s throat. NATO can’t spit it out, nor can it swallow. It is disfiguring NATO. No amount of propaganda can hide the reality that Afghan people increasingly view NATO as an occupation force. Apart from insufficient troop strength, NATO commanders are in desperate need of intelligence.

The United States’ “pull” within NATO is also in decline. This week, Italian Foreign Minister Massimo D’Alema openly called for the cessation of all US military operations in Afghanistan, except those strictly under NATO command. The change of leadership in France, Germany and Britain doesn’t seem to work quite the way Washington expected.

Therefore, Washington will do its utmost to ward off the SCO’s “encroachment” on Afghan turf. Washington will count on Karzai to smother the SCO’s overtures. The US predicament will be that on the face of it, the SCO initiative on Afghanistan cannot be questioned. Karzai would also look rather foolish if he were to spurn an offer of help from the SCO. After all, the SCO has a legitimate interest in effectively stabilizing the situation in Afghanistan, since the stability of the Central Asian region is linked to it in many respects.

On the other hand, Washington’s grip over the Kabul setup will incrementally weaken once Afghanistan develops an “SCO connection”. Washington should be extremely wary, since Afghans are adept at playing their optimal role in the “Great Game”. Most important, the US will increasingly find itself under compulsion to perform as a team player, which suits neither its geostrategy nor its standing as the sole superpower.

In all this, Pakistan remains an unpredictable player, given the fluidity of its internal situation, even though Islamabad is keen to work closely with the SCO and China. Most of the supplies for NATO forces in Afghanistan pass through Pakistan. It will be quite an irony if a situation develops where the US ends up doing all the fighting in Afghanistan, while the SCO gains in public adulation among the Afghan people and in the wider region as a “nation-builder”.

Last of all, Washington knows that the SCO’s involvement in the Afghan problem ultimately means Russia will be making a big re-entry into the Hindu Kush, apart from foiling the United States’ grand design to steer NATO as a global security organization with global partners. And on July 17, Tajikistan announced that an agreement had been concluded providing for the deployment of Russian combat aircraft on the Ayni Air Base outside Dushanbe. Indications are that in the first instance Russia will deploy Su-25 jets and Mi-24 and Mi-8 helicopters. The Russian deployment will be within the CSTO framework. Moscow just about stumped the United States’ last lingering hope of gaining a toehold in Tajikistan.

All this pales into insignificance for Washington if the SCO summit favorably views Iran’s admission as a full member. There is only an outside chance at the moment that the SCO will want to wade deep into the fierce crosscurrents in the Persian Gulf region. But Washington will be nervously watching.

The point is, Iran, Russia and China have all “lost” in different ways in the aftermath of the United States’ US$63 billion arms deal in the Gulf region. Washington has once again shown that “the winner takes it all”.

So the “losers” cannot be faulted if they quickly do some homework and see the logic of undertaking some networking of their own to cut their “losses” and maybe even retrieve some lost ground. Certainly, Ahmadinejad will be a star attraction at the SCO summit and his presence in Bishkek will be way beyond the calls of protocol.

M K Bhadrakumar served as a career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service for more than 29 years, with postings including ambassador to Uzbekistan (1995-98) and to Turkey (1998-2001).

This is slightly revised from an article that appeared in Asia Times on August 4, 2007. Posted at Japan Focus on August 10, 2007.

For another recent treatment of the issues, see Marcel de Haas, S.C.O. Summit Demonstrates its Growing Cohesion, Power and Interest Research, August 14, 2007,

See also the author’s

In the Trenches of the New Cold War: The US, Russia and the great game in Eurasia. April 28, 2007.

US Shadow over China-Russia Ties. March 31, 2007.

Moscow making Central Asia its own, August 25, 2006 and other articles by M K Bhadrakumar at Japan Focus.