Modern Life is Rubbish: Miyazaki Hayao Returns to Old-Fashioned Filmmaking

David McNeill

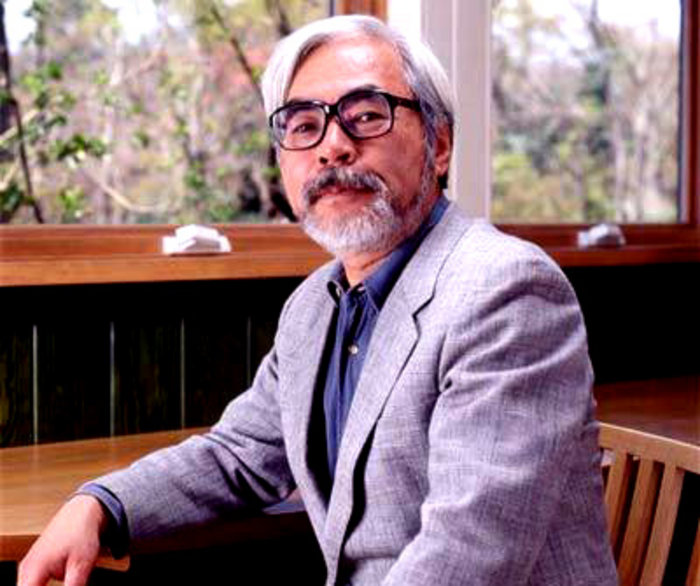

Genius recluse, über-perfectionist, lapsed Marxist, Luddite; like the legendary directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Miyazaki Hayao’s intimidating reputation is almost as famous as his movies. Mostly, though, Japan’s undisputed animation king is known for shunning interviews. So it is remarkable to find him sitting opposite us in Studio Ghibli, the Tokyo animation house he co-founded in 1985, reluctantly bracing himself for the media onslaught that now accompanies each of his new projects.

Once a well-kept secret, Miyazaki’s films are increasingly greeted with the hoopla reserved for major Disney releases. Spirited Away, his Oscar-winning 2001 masterpiece, grossed more in Japan than Titanic and elevated his name into the pantheon of global cinema greats.

Time magazine has since voted him “one of the most influential Asians of the last six decades”. Anticipation then is high for his latest, Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea, which has taken $160m in ticket sales and been seen by 12 million people in Japan alone, and is now set for release in the United States and Europe.

Miyazaki’s 10th movie, the story of a young goldfish that longs to become human, is another chapter in his lifelong struggle to interpret the world of children, explains the director, who says Ghibli has recently built a crèche for its staff where he spends a lot of his time. “I look at them and try to see things as they do. If I can do that, I can create universal appeal.” The relationship is two-way, he says. “We get strength and encouragement from watching children. I consider it a blessing to be able to do that, and to make movies in this chaotic, testing world.”

Humans face a basic choice between love or money, he believes. “A five-year-old understands that in a way an adult obsessed with the economy and share prices cannot. I make movies that can be understood by that five-year-old, and to bring out that purity of heart.”

A stiff, avuncular presence in his tweed suit and math teacher’s glasses, Miyazaki is clearly uneasy dealing with the media circus. It’s unlikely the 68-year-old has heard of British pop group Blur, but he would undoubtedly agree that Modern Life is Rubbish. His movies are paeans to the natural world and coded warnings about its perilous state; in a recent interview he fondly speculated on a natural disaster that would return the planet to its pristine state.

He spends years buried away in this wood-paneled refuge in a leafy Tokyo suburb, painstakingly bringing his creations to life. The director reportedly obsessed for months, for instance, over the color and texture of the sea-waves that wash Ponyo ashore, where she is found by a five-year-old boy. Once the creative process is complete, he has little interest in what happens, moans Ponyo’s producer and Miyazaki’s long-time collaborator Suzuki Toshio. “He gets engrossed in each movie, then when they’re finished he just forgets them and moves on,” Suzuki says

The director has “absolutely no sentimentality” for the finished product. “It doesn’t matter how hard he works or how wonderful the movie is. He doesn’t even like talking about them afterwards. My job is to clean up his mess. To be honest, he’s a pain in the ass! But life is always interesting.”

Having experimented with digital and CG technology on Howl’s Moving Castle, Miyazaki has gone back to basics for Ponyo, which is made up of a stunning 170,000 individual hand-painted frames. He says he has seen none of the landmark digital animations of the past two decades, including Toy Story and Pixar Studio’s recent smash Wall-E, despite being friends with Pixar’s creative director John Lasseter.

“I can’t stand modern movies,” he winces. “The images are too weird and eccentric for me.” He shuns TV and most modern media, reading books or travelling instead. It is no surprise to find that the multimillionaire director’s car, parked outside the Ghibli studio, is an antique Citröen CV, an icon of minimalist, unfussy driving.

Ghibli’s creative engine house is a reflection of its founder’s preoccupation with authenticity and distrust of popular culture. New talent (the studio has just added another 150 animators to its 270 full-time staff) is tested out in a sort of animation boot camp, where the use of cell phones, blogs, iPods and other electronic devices is forbidden.

“Young people are surrounded by virtual things,” he laments. “They lack real experience of life and lose their imaginations. Animators can only draw from their own experiences of pain and shock and emotions.”

He is known to lecture constantly on the need to find harmony between the human hand, eye and brain, and the ever-expanding computer toolbox. Ponyo, he says, is partly about living without technology. “Most people depend on the Internet and cell phones to survive, but what happens when they stop working? I wanted to create a mother and child who wouldn’t be defeated by life without them.”

In a world groaning with increasingly sophisticated movie-making technology, Ghibli’s brand of old-fashioned craft looks as vulnerable as a vintage Rolls-Royce on a highway of speeding cars. Miyazaki himself compares what he does to old clog (geta) makers in downtown Tokyo, now almost extinct, but much prized by aficionados.

Miyazaki understands that his style could become obsolete, claims the Ghibli president, Hoshino Koji, but he doesn’t care. “If the audience disappears, that’s the end of his dialogue with them. He’s not afraid of it. He’s fully aware that this is an old-style operation and that’s why he decided to do a totally hand-drawn animation with Ponyo.”

As both he and Suzuki admit, however, Miyazaki’s uncompromising approach is expensive. “We’ve been doing this for 20 years, and each movie costs more than the last,” says Suzuki. Although the director’s son, Goro, has also recently made his first film, Tales from Earthsea, the studio is still overwhelmingly dependent on the sparse output of its founder. One flop, unlikely as that may be, could devastate the small company.

Enter Hoshino, who has been poached from the rival Disney empire, where he toiled for 15 years. But Ghibli’s new boss denies that his arrival signals an attempt to recast Miyazaki’s Roller as a sleek American sports car. “Miyazaki worked in the US in the early 1980s and came back saying, ‘Forget it, I’m not going to work like that’,” says Hoshino. “But what Disney is good at is exploiting every bit of commercial opportunity. [Ghibli] has done almost nothing in merchandising outside Japan, so we’ll be looking at that, along with foreign distribution.”

Hoshino says a recent tie-up with long-time Steven Spielberg collaborators Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall is an example of the “much more aggressive and open-minded” tack the studio needs to take.

“I don’t shut the door on digital technology either. Just because Ponyo was 100-per cent drawn doesn’t mean we’re stuck with that approach. My job is to come up with the best approach to make the most of Ghibli and try to come up with those untapped opportunities.”

Where does this leave the studio’s maestro?

It is hard to resist the image of a very Miyazaki-ian willful child, struggling to remain unspoiled as the grubby workings of the real world begin to encroach. It’s a theme explored in the story of the boy Sosuke, and Ponyo, the girl- fish whose rage and rebellion against the world result in a devastating storm. “Ponyo’s rebellion is dangerous, but that’s part of life,” explains the director. “Humans have both the urge to create and destroy.”

At a glance

1941: Born, 5 January in Tokyo. Pacifist views profoundly shaped by his early experiences in the ruined city after WW2.

1954: Interest in animation begins after he watches first full-length cartoon.

1963: Begins an apprenticeship at Japan’s Toei Animation studio. The next year he becomes head of its labor union.

October 1965: Marries Ota Akemi. Two sons, Goro and Keisuke, who both now work at their father’s studio, although Goro and he are reportedly on very bad terms.

1979: Directs his first feature, The Castle of Cagliostro.

1984: Releases Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, said to be the first “complete” Miyazaki movie, embracing many recurring obsessions: ecology, pacifism, strong female characters.

1985: Establishes Studio Ghibli.

1997: Princess Mononoke released, Japan’s most successful movie of all time. Wins its director a Japan Academy Award.

2001: Directs Spirited Away, widely considered his masterpiece.

2002: Wins the Oscar for best animated feature.

2005: Receives lifetime achievement award at the Venice Film Festival.

2006: Time magazine calls him “one of the most influential Asians of the last 60 years”.

2009: Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea released in UK.

Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea will be released in the UK in August

This is a slightly revised and expanded version of an article that was published in The Independent newspaper on Sunday, 3 May 2009.

David McNeill writes for The Independent and other publications, including The Irish Times and The Chronicle of Higher Education. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator.

Recommended citation: David McNeill, “Modern Life is Rubbish: Miyazaki Hayao returns to old-fashioned filmmaking,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 19-4-09, May 9, 2009.