By Kudō Hirō , as told to Yamada Seiki; extracts translated with an Introduction by Tom Gill

Introduction

With a population of 3.7 million, Yokohama is Japan’s second biggest city. The last government survey found that in January 2025 only 210 of those people were homeless – down by 28 from 2023 and by 68% from the 692 recorded in 2003, the year when comprehensive national homeless surveys began. While homeless statistics are always open to questions of definition and methodology, there can be no doubt that the city has essentially got the problem under control, as have Japanese cities in general.1 There are plenty of empty beds in Hamakaze (“Beach Breeze”), the city’s only municipal homeless shelter, and teams of outreach workers make regular explorations in search of homeless people who may not know about the facilities available.

Yokohama has tended to have a more progressive approach to social problems than other Japanese cities, and was the first to open a public homeless shelter – Matsukage Temporary Shelter (Matsukage Ichiji Shukuhakusho), hastily opened in 1994. In 2003 this prefabricated building was replaced by Hamakaze, a seven-story, purpose-built facility with 250 beds including 20 for women.

Both of these facilities have been run by a non-profit welfare corporation called Kanagawa-ken Kyōsaikai. Third-sector organizations play a big role in social welfare in Japan, and Kyōsaikai is one of the oldest – founded in 1918, it opened its first lodging house for impoverished workers in 1921. Situated just behind Yokohama Station, it was called Yokohama Social Hall (Yokohama Shakaikan). In 1965 the lodging house was moved to Nakamura-chō and renamed Minami Kōseikan; in 1991 part of that facility was designated as an emergency shelter for homeless people. Then came the Matsukage and Hamakaze facilities. Other cities only started to catch up with Yokohama after the passing in 2003 of the Homeless Self-Reliance Support Law (Hōmuresu Jiritsu Shien-hō), which offered matching funds from central government to municipalities that opened emergency shelters (kinkyū ichiji hinanjo) and homeless self-reliance support centers (hōmuresu jiritsu shien sentā). Uniquely, Hamakaze combines both functions – a sanctuary for people just taken off the street, and a longer-term institution where people can stay for up to six months while seeking employment and saving up the money to relaunch an independent lifestyle after finding a job.

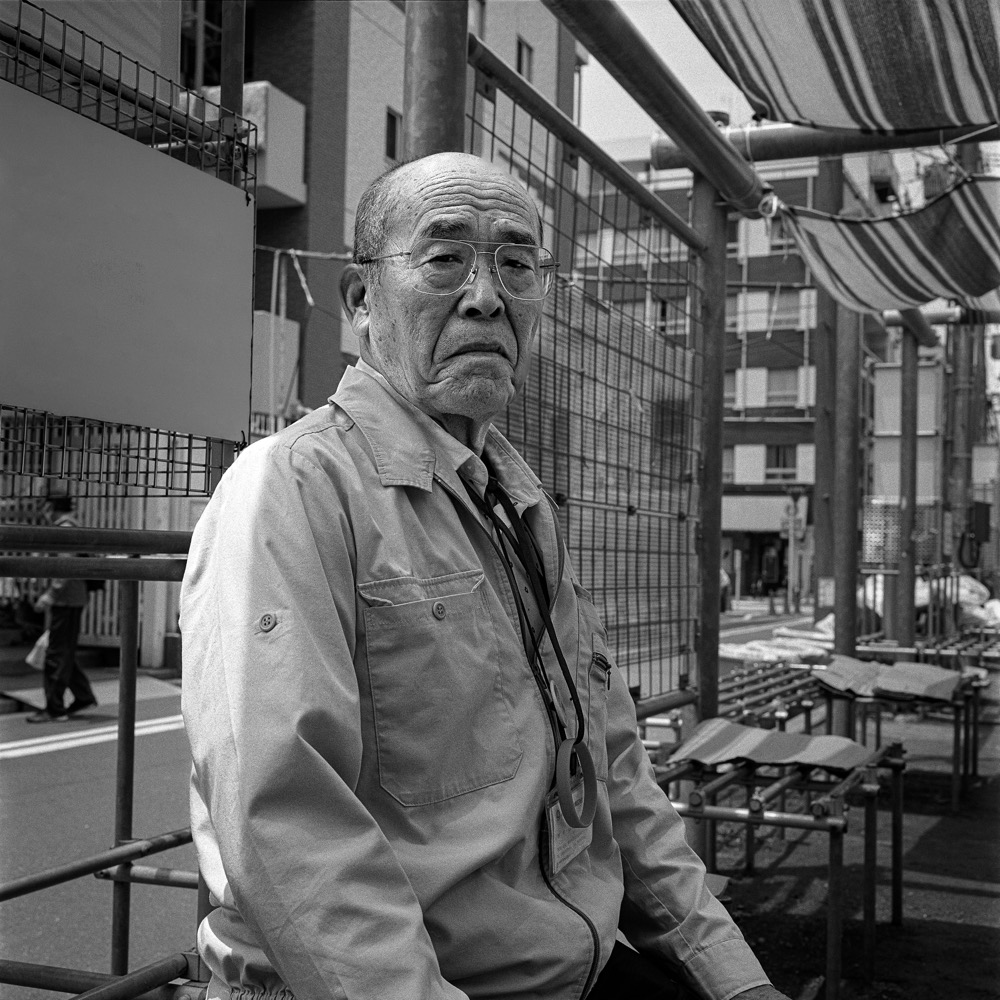

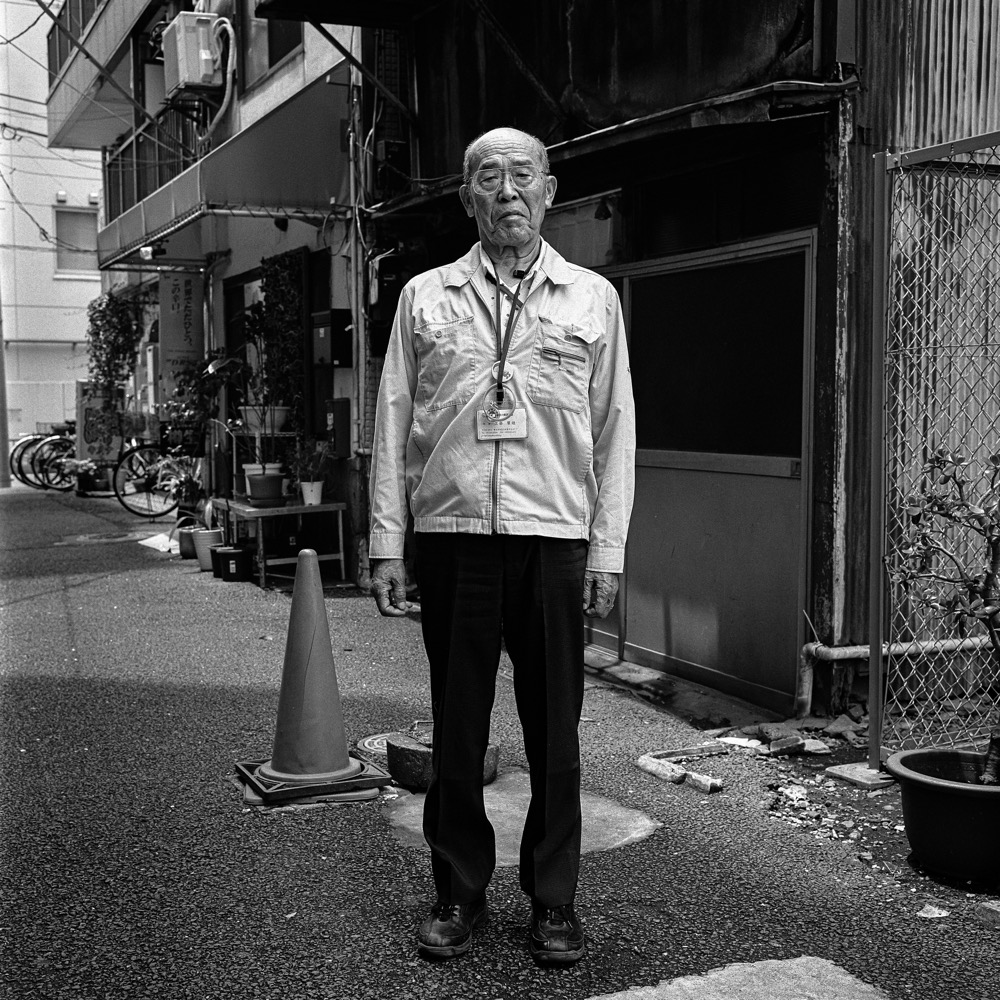

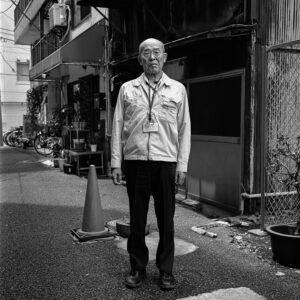

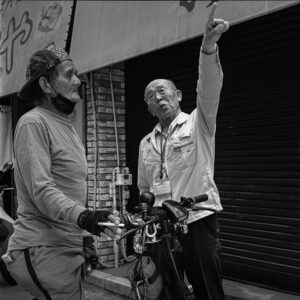

For several decades, a key figure in running the Kyōsaikai homeless support program was Kudō Hirō. Starting out in the 1960s as a humble case worker, he went to serve as director of Minami Kōseikan, Matsukage Temporary Shelter and Hamakaze, which he officially ran from its opening in 2003 until 2015, then serving on the Kyōsaikai board of directors until his retirement in 2021.

I have met Kudō-san many times. He often let me bring parties of students to visit Hamakaze, and even allowed me to stay there for a week while doing research on homelessness in Yokohama. He presents as a gruff and grizzled veteran with a heart of gold. He always insists that places like Hamakaze should give everyone a second chance – including yakuza and criminals, even murderers. In his long career supporting the poor and homeless of Yokohama he estimates he has shaved 7,000 heads – a traditional hygienic precaution. He has cleaned toilets, swept corridors, broken up fights, disposed of corpses and even mopped up the blood after murders. This book is a rare opportunity to get a look at public responses to poverty through the eyes of one who spent several decades at the coal face.

Born in 1946 in Ōtori, a mountain village 44 kilometres from Tsuruoka in Yamagata prefecture, Kudō grew up in poverty. An excellent table-tennis player in junior high school, he had to give up his berth in the regional finals because the family could not afford the train fare to send him to Akita. He graduated from high school in 1964 and was promptly put on a train to Yokohama with a single ¥1,000 note in his pocket, to do menial work in Shimizugaoka Hospital, a welfare hospital for the poor owned by a man who had personal connections with his family, and developed his career in social welfare from the ground up. He was married at 25. His wife Teruko is a nurse and has been his constant companion and support.

Kudō started drinking at the age of 4, when his parents would give him a little saké to help him go to sleep, and quit at 69, after a near-fatal attack of endocarditis left him in a coma for a fortnight – or in his own words, “my heart exploded.” His own experience of limited education, manual labour and alcoholism gave him an empathy with his clients that would be difficult for the college-educated officials who run most aspects of welfare policy in Japan today.

During Kudō’s time as head of Hamakaze, Japan made great strides in combatting street homelessness, as the figures quoted in note 1 show. The system of shelters and self-reliance centers has played a significant role, but the biggest single factor has been a greater willingness on the part of welfare authorities to allow applications for “livelihood protection” (seikatsu hogo), Japan’s social welfare safety net. This softening of the approach to welfare has been prompted in part by the activities of certain NPOs that take people off the street, house them in rudimentary accommodation, and then provide legal assistance to help get their welfare applications approved. Kudō rails against these “poverty businesses” (hinkon bijinisu), as well he may – they tend to take nearly all the welfare money from their clients in the form of excessive rent, utilities and food charges. Nonetheless, Hamakaze exists to serve people who are not welfare recipients, and their numbers are falling fast. Hamakaze rarely has much more than half its beds filled, and this has been the case for some years. While the first half of Kudō’s book recounts hair-raising incidents from the mean streets of Yokohama in the late 20th century, the book later shifts focus to a series of reflections on how his beloved Hamakaze can avoid closure, defend staffing levels, find new roles and preserve the distinctively tolerant culture that Kudō nurtured.

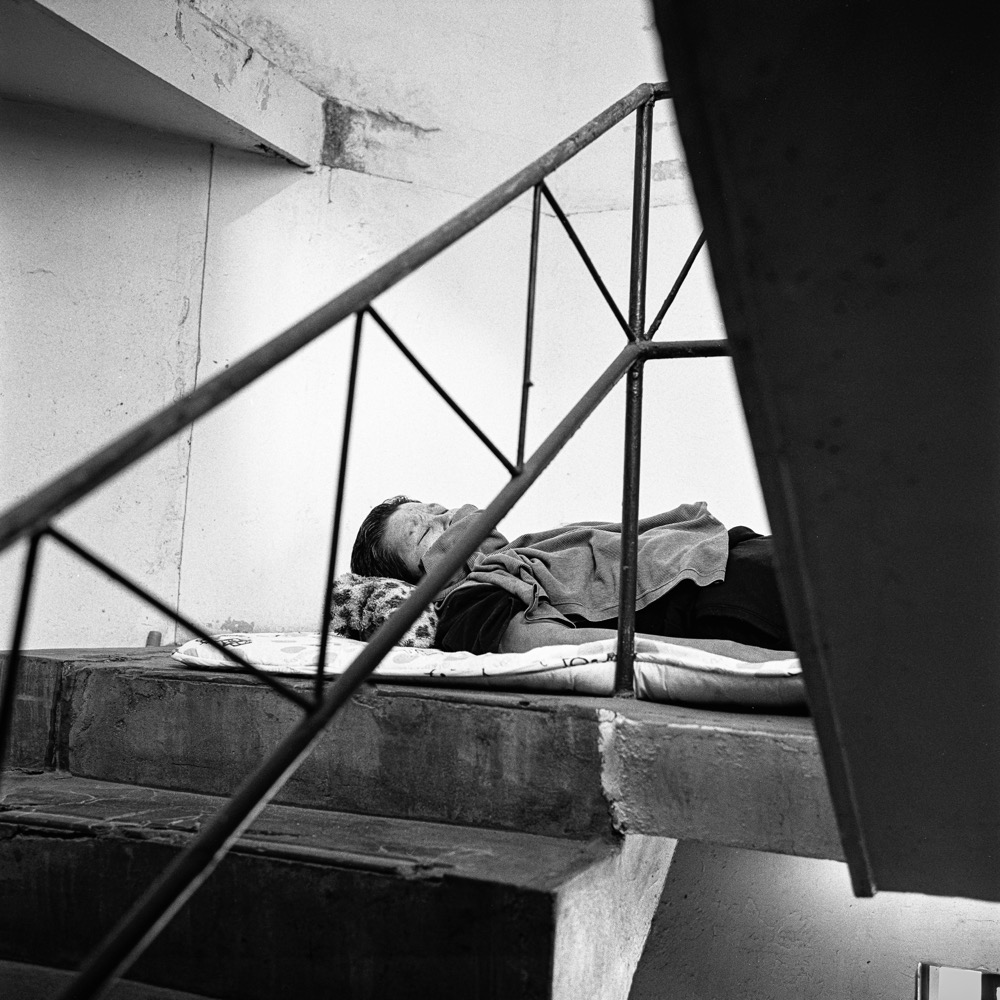

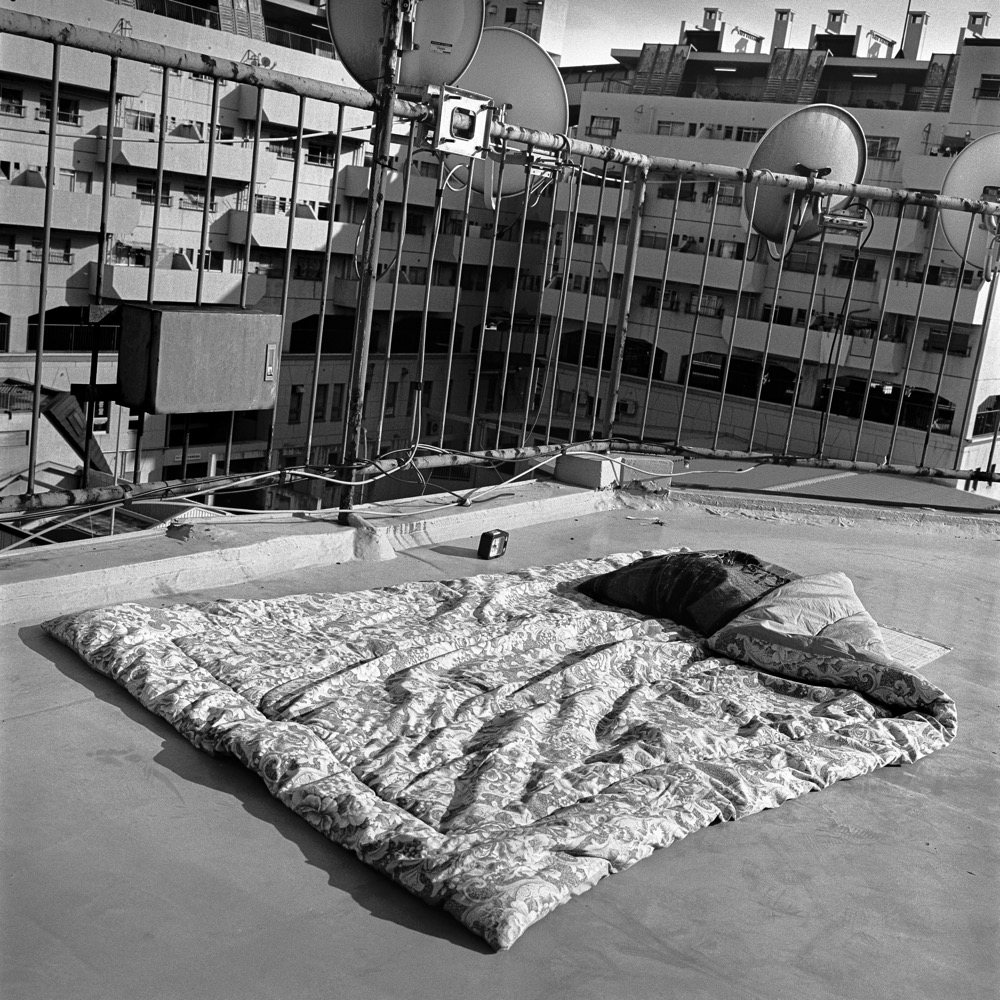

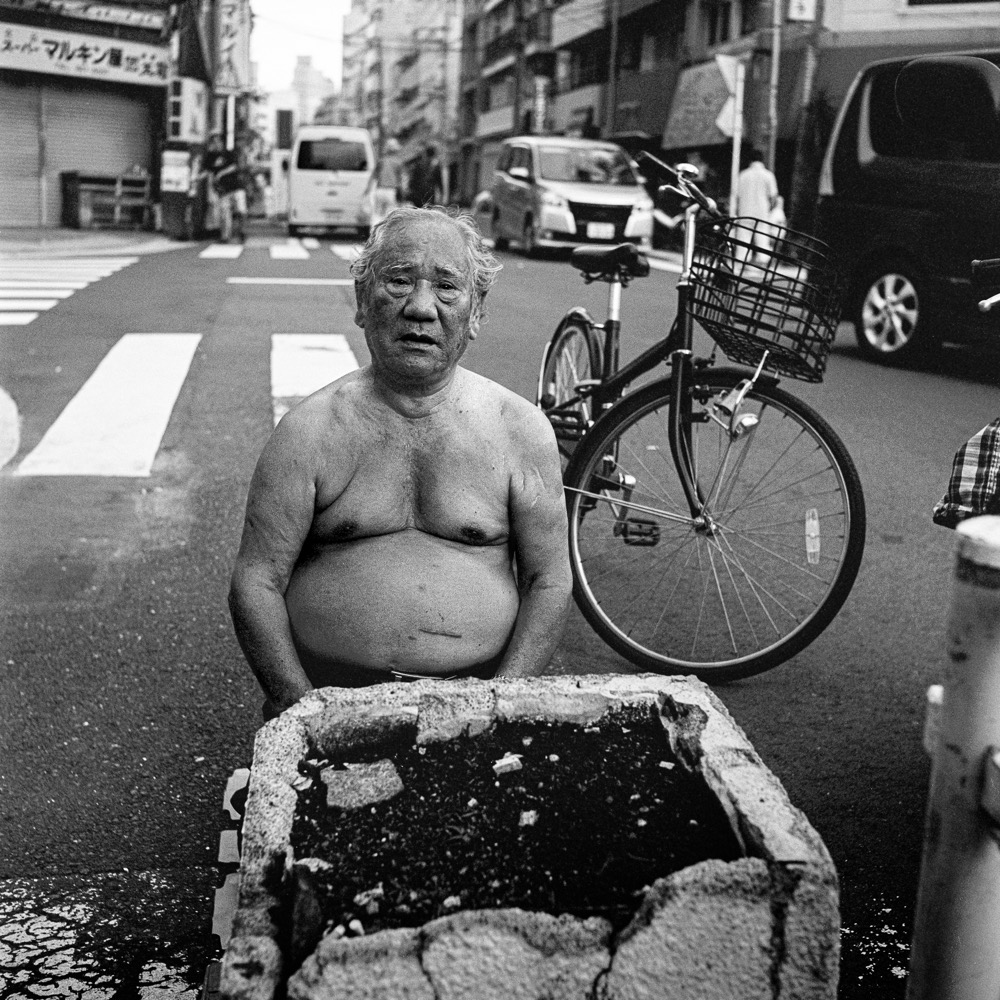

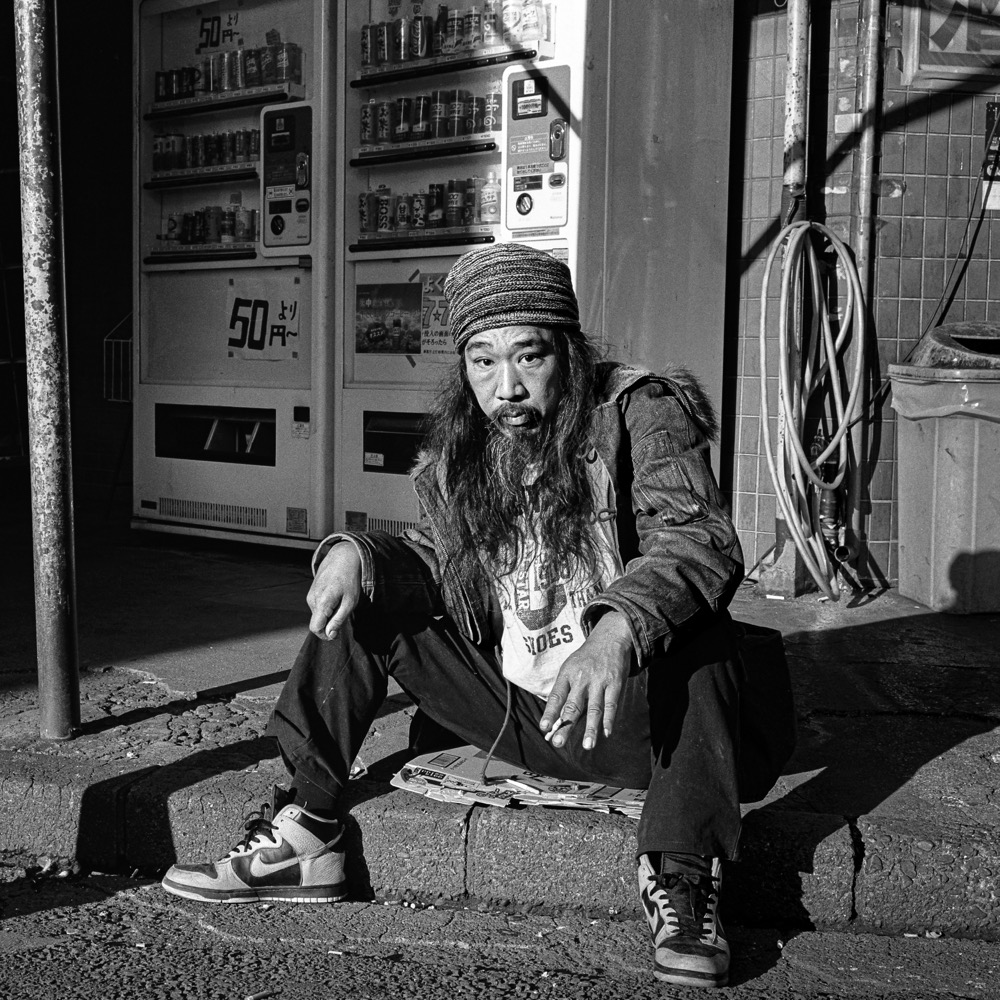

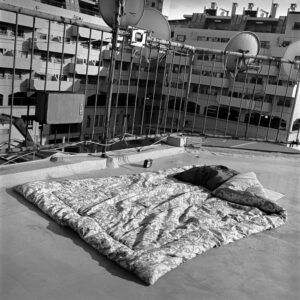

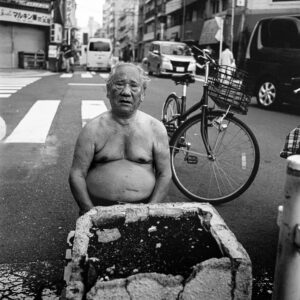

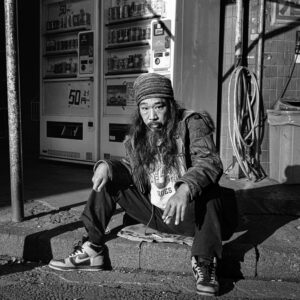

This book was published by Kyōsaikai to mark Kudō-san’s retirement. His memories and thoughts are faithfully reported by Yamada Seiki, an accomplished writer of reportage, known for his study of characters in the slum district of Yokohama where Hamakaze is located, “The People of Kotobuki-chō” (Kotobuki-chō no Hitobito, Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2020), with brilliant monochrome photography by Kojima Ichirō, whose lens has been documenting life in Kotobuki-chō for decades. Check out the gallery of 35 of his works attached to this article. The extracts below are my own edited translations from Oy, Kudō. The book is not available for sale, but the entire text may be read online and downloaded as a PDF here: https://kyosaikai.jp/k-book/#page=1. A careful reading of it shows how Kudō’s checkered life experience has given him a distinctive outlook on welfare issues. Sometimes he sounds extremely liberal; at others, almost shockingly old-fashioned. But as he says himself, the consistent thread informing his approach to social welfare is his grounding in a small rural community in a harsh natural environment. So that seems a good place to start this collection of extracts.

Tom Gill

Click the above image to view of gallery of photographs of Kudō Hirō and the Hamakaze district by photographer Kojima Ichirō .

1. My Hometown in Yamagata

Let me share a little about my hometown because I often feel that my experiences there shaped the core of how I think. I was born on January 10 1946, in the Shigeoka district of Ōtori, which in turn is part of Asahi Village, Higashitagawa District, Yamagata Prefecture. In the past, the area thrived due to mining: at its peak, Ōtori had about 1,500 residents. Today, there are only 53 people left. Shigeoka has just ten houses and 13 people left, and the youngest resident is 80. He takes care of the duties generally allotted to “youngsters”. The other residents are very old people trying somehow to preserve their ancestral land.

The snow starts falling in Ōtori around November and it doesn’t fully melt until May. The snow piles up to three meters, so every house has entrances on both the first and second floors. In winter, we used the second-floor entrance. Our old house had a thatched roof and a cowshed just inside the front door. If we didn’t bring the animals into the house, they would freeze to death. That’s probably why I’ve never minded the smell of animals.

I’ve always believed that poverty and destitution are two different things. My family was undoubtedly poor, but I don’t think we were ever destitute. What’s the difference? Poverty simply means lacking money or basic necessities. Destitution means lacking money or necessities and being isolated: being poor with no one to help you. In that sense, my family was poor, but we were never destitute. In my hometown, if someone was short on food, neighbours would drop by, saying, “Here, have some of this.” That’s the kind of community we had in Ōtori. You could call it “love thy neighbour.”

I had a passion for catching living creatures. I caught fish for the table, and set traps for weasels, raccoons, and wild rabbits. If I caught a rabbit or weasel, I wasn’t sad – I was honestly happy. I’d knock the animal unconscious with a stick, take it home, and carefully skin it with a knife. In spring, a fur trader would visit the village. If I’d skinned the animal well, he’d say, “Hey, Hirō, this is a fine weasel!” And he’d give me 600 yen instead of the usual 500. People might criticize me for hunting and eating wild animals, but to me, using the meat as well as the fur shows true respect for the animal’s life. City people don’t understand that kind of thing.

2. Lessons from the Yakuza of Kogane-chō

This extract is from the 1960s, when Kudō was in his twenties and working as a “medical social worker” (iryō sōdan’in) at a welfare hospital in a rough part of Yokohama.

Most of the people who visited Shimizugaoka Hospital were from the slums of Kotobuki-chō and Matsukage-chō, but because the hospital’s location was also near Kogane-chō and Hinode-chō, the women who worked in the chon-no-ma brothels there often came to see the doctor as well.

The area under the elevated railway tracks between Kogane-chō and Hinode-chō became known as an aosen or “blue line” district – a private pleasure quarter where illegal prostitution took place, as opposed to akasen or “red line” districts, the publicly-run prostitution zones closed down by the allied occupation authorities in 1946. The Kogane-chō women who came to Shimizugaoka Hospital had neither health insurance nor money to pay for treatment. So when the treatment was finished, they’d say, “I’ll come back and pay later.”

After giving them a few days, the hospital’s director, Mr. Uchida, would say, “Oy, Kudō, go to such-and-such a bar in Kogane-chō and get the money for the treatment.”

This was one of my jobs as a “medical social worker.” There was nothing for it: I had to go to some seedy dive in Kogane-chō and say, “Sorry, I’m from Shimizugaoka Hospital and I’ve come to collect payment for medical treatment.” Then some yakuza, the guy who ran the place, would come out from the back and say, “You idiot, she went to your hospital because she didn’t have any money. If she had any money, she wouldn’t have gone to your crappy hospital.” So I often came back empty-handed, having been bawled out for daring to ask for payment.

But when I submitted a report saying that I’d gone to collect the money but didn’t get it, that was the end of the matter. I was never asked to go back.

In fact, Shimizugaoka Hospital was one of the hospitals designated as a “free or low-cost treatment facility” (muryō teigaku shinryō shisetsu), which in essence meant that people with no money could receive treatment for free or at little cost. Even today, Shimizugaoka Hospital is one of more than twenty free and low-cost treatment facilities in Yokohama, including Yokohama Ekisaikai Hospital and Ushioda General Hospital. Apparently, if a guy like me submits a report saying that they went to collect the treatment fees but were unable to do so, it helps them get their taxes down. Mr. Uchida probably sent me to those bars to collect the money knowing full well that it would be a fool’s errand.

I could say a few things about Mr. Uchida, but thanks to the many times he sent me on fruitless debt-collecting missions to the chon-no-ma, I became the sort of guy who could swap a bit of banter with the yakuza who ran them. Of course, I didn’t mess around with the girls there!

I learnt a few interesting things from those yakuza.

A chon-no-ma is a tiny, two-story, two-room building, with a bar on the ground floor run by a single hostess, and a bedroom upstairs for later. There is usually a magic mirror at the back of the bar, behind which a bouncer hides and carefully observes the incoming customers. The hostess serves the customer a beer to get them in a relaxed mood, then chooses the right moment to invite him upstairs, but sometimes a customer just wants to enjoy a cold beer and heads for the door once he’s drained it. That’s the moment when the bouncer pops out from behind the magic mirror.

“Hey, wait a minute, you’re messing with our girls!”

And they’ll charge the guy a whole lot of money for that one bottle of beer. You have to get the customers upstairs, you see, otherwise you wouldn’t have a viable business.

It’s all wrong, of course, but at the time I didn’t see much point in upsetting the yakuza who ran the chon-no-ma. I guess that’s why they never tried to bump me off. Anyhow, one day a yakuza boss gave me a handy piece of advice.

“Oy, Kudō. If the same drunk shows up at the entrance of the hospital where you work three times in the same day, remember this: I am behind him.”

Kind of scary, eh?

There were quite a few drunks who would wander up to the entrance of Shimizugaoka Hospital and get in a tangle with the security guard, but a drunk who left after a single visit was just a drunk. However, if the same drunk came back several times on the same day, that meant he was a “hired drunk,” sent by the yakuza. It was a sign from the yakuza that they had something to say to your hospital.

“Oy, Kudō, if the same guy shows up three times, you better ask yourself why he’s come three times.”

“Got it, boss!”

I’m glad to say we never received such a warning while I was there.

In Kanoedai, near Shimizugaoka Hospital, there was a well-known yakuza gang called the Hayashi Family, run by three brothers and affiliated to the Inagawa-kai syndicate. Shimizugaoka Hospital did not discriminate against anyone, be they homeless or living in a run-down flophouse, so I think members of the Hayashi family were sometimes treated there too. Perhaps because of that, these tough gangsters were exceedingly courteous to us.

The Hayashi Family controlled a band of nagashi – guitar playing troubadours who would roam from bar to bar playing requests for tips – so around sundown I’d often see them streaming down the hill from Kanoedai towards the downtown area, guitar in hand. Seeing them reminded me that yakuza are not born that way: they become yakuza for all sorts of reasons, so we shouldn’t look down on them. Just as with the homeless, I think we should look at people just as they are, not judging them by their occupation or background.

Drug abuse was also rampant in Kogane-chō at the time. In the old days, methamphetamines were called hiropon,2 and it was rumoured that you could buy as much as you could afford to pay for at the pharmacy in Kotobuki-chō. A lot of the dockworkers were using hiropon. They would do two or three shifts back-to-back (nibu-tōshi, sanbu-tōshi), sometimes even nine or ten shifts, meaning they’d work four or five days straight, just taking the occasional nap inside the ship. When you’re doing such gruelling work, a shot of hiropon will pep you up – just for a while.

There were also many people selling blood. There was a blood bank behind Yokohama City University Hospital, and if you popped your arm through a small window, they’d stick in a needle and take your blood. When I started working at Shimizugaoka Hospital, the market price was about ¥1,200 for 400cc. In those days, when the starting salary for a government worker was around ¥15,000, it was really good money. It was a seedy business though.3

In the past, Kogane-chō was a difficult town, with the chon-no-ma and many drug addicts, but there was a member of the Kogane-chō Town Council called Nakata Shiro who was a Catholic priest, and he confronted the drug problem head on. He used to yell at the yakuza so loud you couldn’t tell which was the priest and which was the yakuza. I was battling the drug problem every day at Shimizugaoka Hospital myself, so I was deeply moved to see this amazing person in action.

3. Two Murder Cases

In 1978, Kudō moved to Minami Kōseikan, a small welfare lodging house, his first position with Kyōsaikai. He was one of just four staff there. Ten years later, in 1988, he would be promoted to head of this facility.

During my time at Minami Kōseikan there were two murder cases right there in the building. These awful events really drove home the difficulties of communal living.

The first murder happened in a four-person room. There was a man, Mr. A, who was very considerate of his roommates. Whenever he got paid, he would buy saké and go around pouring it out for his three roommates, thanking them for their kindness towards him. Among the three roommates was a disabled veteran with a prosthetic arm. He couldn’t work but got by on his disability pension. Every time Mr. A offered him a cup of saké he’d say ‘What, cheap sake again?’ This wasn’t just once or twice – for months, he kept on rubbing in his ingratitude.

One night, while I was working in the office on the second floor, Mr. A came in carrying a carving knife wrapped in old newspaper. He suddenly said, ‘Mr. Kudō, thank you for everything.’

‘Mr. A, what are you doing with such a dangerous thing?’

‘You’ll understand if you go to the fourth floor.’

When I rushed up the stairs to the fourth-floor room, I found the tatami room was a sea of blood, with the disabled veteran lying in the middle. Mr. A had finally snapped after enduring months of being mocked about his ‘cheap saké.’ He turned himself in to the police and told them everything.

The second murder case was just as tragic. When a public lodging house in Minami ward was being renovated, a taxi driver temporarily moved into Minami Kōseikan. He was placed in an eight-person room. While the bunk beds were separated by curtains, sounds naturally carried through. One day, when the taxi driver returned from work – he’d be doing 20-hour shifts, as many Japanese taxi-drivers do – he heard a tapping sound coming from one of the bunk beds. He couldn’t sleep because of the noise. After this continued for several days, he suddenly pulled open the curtain of the bed the sound was coming from and found an elderly resident chopping ingredients on a cutting board. The tapping was the sound of a knife chopping food.

Cooking wasn’t allowed at Minami Kōseikan, but this old boy couldn’t eat normal food because he had no teeth. So he would buy ingredients, chop them finely, and cook them until soft in a pot over the coal-fired stove used for warming the room. This clearly violated the facility’s rules, but I pretended not to notice.

However, the taxi driver who had come from the public lodging house took advantage of this rule violation. He threatened to report the old boy to the management unless he went shopping and made sashimi for him to eat after each day’s work – he did at least give him the money to buy the fish. The elderly man had no choice but to slice up the sashimi as ordered, ready for the taxi driver’s return, to keep him quiet.

After three weeks of preparing the taxi driver’s meals, in the fourth week, the elderly man stabbed the taxi driver to death with his carving knife.

I know it sounds drastic. He must have been driven by fear of being forced onto the streets if the management found out he was breaking the rules, resentment towards the taxi driver’s arrogant attitude, and who knows what other conflicting feelings.

The elderly man appeared at the office door with the bloody carving knife.

‘Mr. Kudō, I couldn’t take it anymore, so I killed him. I’m going to turn myself in at the Nakamura-chō police box,’ he said, handing me the knife before leaving.

I feel very sorry for the victims’ families, but after hearing the detailed circumstances of these two cases, I couldn’t view the perpetrators as entirely evil. Of course, I’m not saying it’s okay to kill people, but I did feel sympathy for both perpetrators.

The police came later for the crime scene investigation, but they only took photos and removed the bodies – they didn’t clean up. After they finished, they just said ‘We’re done’ and left quickly. So I had to mop up the blood-soaked room and hallway myself. None of the residents offered to help. I just did it in silence. Part of the job.

Both perpetrators got sentences of eight years, but once they’d done their time, I allowed them to return to Minami Kōseikan.

4. Thoughts on Human Rights

In the 1980s, Minami Kōseikan started taking in homeless people, as Kyōsaikai started shifting its focus from the welfare of poor working men towards the newly newsworthy issue of homelessness.

After the notorious 1983 Yokohama Homeless Murder Case, in which four homeless men were beaten to death by schoolboys who left the bodies stuffed into rubbish bins and claimed they were “cleaning up the city,”4 we started accepting homeless people at Minami Kōseikan. This led to my meeting two unforgettable individuals.

One was a 29-year-old man with polio. He’d run away from a home for the disabled and was sleeping rough at Yokohama Station’s west exit. We took him in, and he stayed in a tatami room on the fourth floor of Minami Kōseikan. He was quite smart.

Even after moving in, he’d go to the station to give emotional speeches and beg for money. I went to watch once. He’d struggle to speak clearly: “Thank you all for your hard work. I want to work like you, but I can’t with this body. I’m very hungry. Please help me!” He’d return later and gleefully show me all the cash he’d collected.

His family managed his disability pension, so I guess he had no cash on him when he ran away from his previous institution. Even so, he was receiving disability benefits, and he wasn’t as hungry as he made out in his eloquent speeches. I pointed out that his appeals for cash were a form of fraud. In response he told me to come to the ‘mammoth’ police box near Yokohama Station’s west exit on a certain date and time. Doing so, I was surprised to find homeless people drinking in a circle on vacant land near the police box. The donations were financing these drinking parties. He said, “See – it’s not just for me. I collect donations for everyone to enjoy. Want to join us, Kudō-san?”

I have to admit I was impressed. I almost applauded his craftiness. But he died in Minami Kōseikan about a year later. He was found dead in his futon one morning. I have a horrible feeling that the charcoal braziers that were all we had to heat the building might have killed him by carbon monoxide poisoning. The ventilation in his room wasn’t great.

The other unforgettable person was an old guy who came in after the series of schoolboy assaults on homeless men. During his interview, he said he was one of the victims. His accent was like mine – he was from Yamagata.

Strangely, he never spoke ill of the boys who assaulted him. When I asked why, he blamed society and education for their behaviour. I wondered about his background. It turned out he was a former junior high school headmaster from a town I knew in Yamagata – a serious person whose only pleasure was having an evening drink with his wife’s home cooking. After retirement, though, he started drinking from morning on. Perhaps it was a reaction to decades of proper behaviour at the school.

In a small town, rumours spread fast. People called him an alcoholic and blamed him for their children’s poor performance. They taunted him in the street. His wife and children couldn’t bear the stigma. Things got worse at home until one day, after an argument, he left home and headed for Tokyo. He ended up in Kotobuki-chō, staying in cheap lodgings when he had pension money and sleeping in Yamashita Park when he didn’t. And finally this former headmaster was beaten up by a bunch of schoolkids.

Meeting him made me first consider the true meaning of human rights. Growing up in the mountains of Yamagata, I viewed humans and animals as coexisting. I never found animal smells disgusting or unsanitary. In Yokohama I bathed homeless people not because they were unclean, but to make them feel refreshed. I never discriminated against homeless people, unkempt individuals, or disabled people. It wasn’t because of some abstract concept of human rights – more like a simple awareness that with my background, I could easily have been the one needing support. I always think, “What if this were me?” “What if I were homeless?” “What if people called me an alcoholic?”

People talk about “human rights” pretty casually nowadays, but I never learned about it in school. I just learned the importance of mutual acceptance from country life. Claiming rights without mutual acceptance is meaningless, isn’t it? The headmaster never used the word “human rights.” If someone had acknowledged him as a good educator instead of labelling him an alcoholic, he might have enjoyed retirement with his family. After meeting the headmaster, I resolved to accept anyone, be they homeless, be they yakuza. This conviction remains.

I visited the headmaster at his lodging house several times, offering to accompany him back to Yamagata. But he wouldn’t have it. He was over 70 when I was about 40. He died alone in the lodging house. Thinking he probably called for his family in his final moments, I wept with frustration.

I don’t even know what happened to his ashes. When someone dies in our welfare facilities, the authorities retrieve the body, cremate it, and do their best to contact family members. If the family agrees to accept the remains, they’re sent there. Otherwise, they become “unclaimed.” Then they’re interred in a pauper’s cemetery in Kuboyama, Nishi ward. They used to keep the ashes in an urn for five years, then throw them into a big anonymous grave with all the others if they were still unclaimed. Nowadays they only keep them for three years. After 1964, the prefecture set up a special tomb at Shōkanji Temple in Hodogaya for the unclaimed remains of people who died at welfare facilities. But when I tried to arrange the headmaster’s burial at Shōkanji, officials claimed that the status of his bodily remains was ‘private information’. How absurd! Only city or prefecture officials can view names – we outsiders cannot. So I don’t know if the headmaster returned home or lies in Kuboyama. I wonder if he’s there whenever I visit Kuboyama.

5. The Need for Flexibility in Social Welfare

In 2003 Kudō became the first director of Hamakaze, Japan’s first ever purpose-built facility for homeless people. His approach to management of this facility was distinctive and sometimes controversial.

As the director of Hamakaze, I always tried to make the rules flexible. Sometimes it meant breaking other people’s rules.

Take cigarettes, for example. Since my time at Minami Kōseikan, I had been distributing 10 cigarettes per person every day to residents who were smokers. (I gave non-smokers little snacks instead.) I did the same at Hamakaze – because I consider cigarettes a kind of tranquilizer for homeless people. So when we were inspected by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare’s bureau chief, I would always make a point of stopping in front of the smoking area on the third floor and declaring: “Even though the Health Promotion Law says smoking isn’t allowed inside welfare facilities, cigarettes are essential for Hamakaze’s users, so as long as I’m director, I’ll keep providing them. Even if Yokohama City says no, I’ll pay for them myself.”

However, while Hamakaze initially provided ten cigarettes, it was reduced to six, then three, and after I left as director in 2015, it finally went to zero. What’s happening now that they’ve stopped providing cigarettes? Users pick up discarded cigarette butts in front of Hamakaze’s entrance, or stand next to people smoking, waiting for the moment they throw away their butts. How would you feel if you were in their position?

As with cigarettes, I believed cash distribution should also be handled flexibly. In the days of the Matsukage Temporary Shelter, we gave residents 500 yen in cash for lunch money, but at Hamakaze, we boldly gave a thousand yen to those who were going to work while living at Hamakaze. So if someone found work and ended up working five or six days a week, they would receive 5,000 or 6,000 yen a week until they got their first salary. The payments stopped after that. It would be a human rights violation for Hamakaze staff to contact workplaces asking “Is so-and-so really coming to work?” so we couldn’t do that. Naturally, this raised concerns that people might run away with the money.

But I saw things differently. Residents who receive a thousand yen realize they’re being treated as a responsible individual. That feeling gives them a sense of independence and makes them more likely to follow rules within Hamakaze. The more you try to force people to follow rules, the more resistance you get. Conversely, if you trust and recognize clients, they naturally start following rules. That’s the meaning behind giving cash to users who have found work.

Another aspect of my flexible approach was the timing of interviews. Many people who enter Hamakaze have backgrounds like being former yakuza, drug addicts, alcoholics, compulsive gamblers etc. How would they feel if we immediately bombarded them with questions like: “Where’s your registered address? Do you have family? What kind of work have you done until now?”

That kind of interrogation makes people feel they’re being treated like criminals.

So I would leave them alone for the first week, letting them eat meals and take baths at their leisure, and learn a bit about their background through casual conversation. Only after building some rapport would I ask about their previous work. Once we had developed a relationship, users would happily share detailed stories about their past work. That kind of information would help us find new job opportunities for them.

It’s no good badgering people about job-hunting the moment they come through the door. Homeless people are often too tired from life on the streets to think about looking for their next job.

Speaking of employment, shared rooms have their advantages. Most of the rooms at Hamakaze have six or eight beds. So when we start challenging people to think about getting a job, they can ask their roommates for advice.

It’s also important for staff to provide various consultations during the six months while people are working and staying at Hamakaze. We carefully simulate scenarios: rent will be this much, food costs this much, utilities will be this much, so you’ll need to make at least 150,000 yen per month. Even more important is the “post-discharge support” after they leave Hamakaze and move into apartments. People can easily end up feeling isolated after moving into private apartments. That’s why it’s essential to maintain regular patrols and have a system where people can consult about problems anytime.

As for those who don’t manage to find work before their discharge deadline or who end up back on the streets even after moving into an apartment, instead of dismissing them as hopeless cases, it’s very important to tell them “You can come back anytime.” That’s Hamakaze’s special appeal.

Hearing all this, you might think Hamakaze is too soft on its residents. But in my view, Hamakaze has to be flexible. This isn’t just for the users’ sake – it’s for the facility’s sake too. Nowadays the supply of welfare facilities is outstripping demand, so we have to differentiate ourselves or risk a falling occupancy rate that could lead to staffing cuts or even being shut down. A lot of homeless shelters have shut down in big cities across Japan. Today, Hamakaze is the only public welfare facility in the whole country that specializes in homeless independence support. Our flexible, humanistic approach to clients is the key to our survival.

6. Homelessness versus “Financial Distress”

As the street homeless population fell, the national government redefined the clientele of self-reliance support centers, broadening it to include people who were struggling with poverty even if not actually homeless.

In March 2015, following the implementation of the “Act on Support for Self-Reliance of People in Financial Distress” (Seikatsu Konkyūsha Jiritsu Shien-hō) Hamakaze was rebranded from a “Homeless Self-Reliance Support Facility” to a “Self-Reliance Support Facility for People in Financial Distress.” This was no mere name change – I believe this shift significantly contributed to the decline in users. Specifically, the rebranding drove away “genuinely homeless” individuals. To them, the term “people in financial distress” refers to those who are unemployed after losing jobs or working on low wages – individuals closer to society’s mainstream than themselves. So a lot of guys who previously relied on Hamakaze began to think, “Hamakaze doesn’t take people like us – the homeless – anymore.” Even with twice-monthly outreach consultations and proactive engagement, few now want to enter the facility unless they’re in dire physical condition.

Of course, the problem isn’t just the name. Hamakaze’s operational approach also changed. As I mentioned, new residents used to spend their first week resting and recuperating. But once the law took effect, health checks and interviews began the day after arrival: “What jobs can you do? What career do you want to pursue?” Staff must compile reports on these interviews and submit them immediately to Yokohama City, which then forwards them to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The legal revisions imposed these requirements, but I wonder whether ministry officials really read these daily reports. In my view, this is mere bureaucracy, but its impact is profound. Among Yokohama’s homeless community, rumours have spread: “They’ll nag you to work if you go to Hamakaze. That’s why I avoid it.”

Realistically, people need time – to eat Hamakaze’s good hot meals, bathe, and regain their strength – before they can even begin to think about rebuilding their lives. I’ve repeatedly explained this to the authorities, but they never seem to grasp it. This issue remains unresolved for me, lingering like indigestion even after leaving my role as director.

7. A Modern-Day Ubasute Mountain

“Ubasute”, literally “throwing away old women”, refers to the ancient practice of abandoning old people, especially women, to die on the side of a mountain.

While some social problems ease off, others get more acute. Yes, Japan now has a homeless population that is very low by global standards. But our aging society has a massive and growing problem with dementia. I wish the authorities would be flexible enough to allow Hamakaze to take in elderly people with dementia. Of course that would require hiring two or three more nurses and seeking funding from national and local governments. It can’t be done overnight, but I don’t think it’s impossible.

I also think it’s time for a serious discussion about things that are currently considered taboo – like locking people into individual rooms at night, using physical restraints when people become violent, or administering sleeping medication at bedtime. I know a lot of people would call such measures abuse or harassment. But what is the alternative? Noisy and violent behavior ruins life for all the other residents. When facilities are unable to control their residents, they have no choice but to discharge them. Where to? Back to their long-suffering families? Onto the streets? Is that an improvement? I believe we need to have these discussions properly, or else our streets will become a modern-day ubasute mountain.

Let me tell you something that happened when I returned to my hometown in Yamagata one time. I saw an old woman I’d known for years walking along a farm path with a rope tied around her waist, like a dog being walked. The woman holding the rope was her daughter-in-law. I asked my big brother, “What’s going on there?” He explained that the old woman had developed dementia. The daughter-in-law knows about day-care services and could take her there, but it’s quite a distance. It costs money, and there’s the travel to pay for too. The elderly woman’s pension isn’t nearly enough, and taking her to day-care would eat into the daughter-in-law’s time for housework. So she walks her with a rope around her waist instead.

“Hirō, don’t go telling outsiders about things that shame our village,” my brother warned me, but I didn’t think it was shameful at all. In fact, I felt sympathy for the daughter-in-law. Because regardless of whether others call it abuse, she’s still making sure the elderly woman gets her exercise. Better to be tethered on a lead than to be abandoned on a mountain.

8. The Hamakaze “Work Challenge”

Employment programs are an important part of Hamakaze’s work.

For some 15 years, Hamakaze has been running a “Work Challenge” course, working with several cleaning companies in an effort to give work opportunities to unemployed people in the Kotobuki area. The course includes classroom learning and practical training: it runs from morning to evening and can be completed in two months. Naka ward5 provides the funding, and Hamakaze staff handle the operations. Case workers from the Naka Welfare Office select and approach potential participants from among Kotobuki’s welfare recipients.

Initially, we talked about ending it when we reached 600 total participants – about 10% of Kotobuki’s population – but the program has been extremely successful and may be extended. In fact, 70% of participants find employment. Of course, some don’t stay in their jobs very long, but still, a 70% employment rate is brilliant. The Yokohama authorities have started trying to open it up to welfare recipients living in other parts of Naka ward besides Kotobuki. That’s no easy matter, since Kotobuki-chō is so stigmatized by those who don’t know the place, but there are signs of progress.

The Work Challenge course has given me many unforgettable moments. Like when people who found jobs would rush to Hamakaze saying, “Mr. Kudō, I got a job!” The first graduation ceremony was particularly memorable. We had media, famous writers, and various people coming to cover this story about teaching job skills to welfare recipients. We got Kyōsaikai’s Managing Director to present the certificates, with the Naka ward mayor also in attendance.

“To [name], this certifies that you have completed the Work Challenge Course…”

When the managing director read out the first participant’s certificate, I was amazed – the man received it with both hands like a schoolkid getting their graduation diploma, tears streaming down his face. So just as the boss was about to say “same as above” for the rest of the graduates, as they do at Japanese graduation ceremonies, I asked him to wait.

“I know it’s a bother, but please read out the full text for each person.”

For many participants, this was the first time since junior high school that they’d received a certificate with their full name and their achievement being read out at a proper ceremony. I guess that’s why receiving a completion certificate with their name being called out meant so much to them. That’s why I asked for the full text to be read out.

We still hold these ceremonies, and each one is moving. When a guy called Yōichi Matsumoto from the eighth cohort graduated from the Work Challenge course, he gave me this acrostic poem:

To Mr. Kudō Hirō:

K… Keeping patient with all our troubles

U… Understanding us when we’re hard to deal with

D… Directing us so skillfully

O… Offering our thanks for

H… Helping us day after day

I… In appreciation of your

R… Relentless efforts

O… On our behalf

O… Our deepest gratitude6

It brought tears to my eyes.

The Work Challenge Course graduates have formed an alumni association called the “Walking Group” (ayumu kai). “Walking” uses the character written on the shōgi piece corresponding to a pawn in chess. Just as a chess pawn can promote to a queen, a shōgi pawn can promote to a piece called “gold” – the character for which is written on the other side of the piece. The members got together and chose this name themselves. They’re all hoping to turn themselves into gold. I hope they make it to the end of the board.

Notes:

- Tokyo: 520. Osaka: 726. Nagoya: 72. National total: 2,072, down 9% from 2024 and by 91% from the 25,296 recorded in 2003. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Press Release, April 26 2024. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12003000/001477787.pdf

- A slight distortion of ‘Philopon’, a brand of stimulant launched in 1941 by the Dainippon Pharmaceutical Company, derived from the Greek philo (love) and ponos (labor). Hiropon was used as a general slang term for stimulant drugs well into the 1980s.

- Kudō does not go into detail, but it is well known that alcoholics and drug addicts would sell blood far more often than was healthy for either them or the people receiving the transfusions. The buying and selling of blood was not banned in Japan until 1990.

- See pp. 177-178 of my book Men of Uncertainty (SUNY Press, 2001) for a brief account of this case. Sae Shūichi has a much more detailed account in his Japanese-language book, Yokohama Sutorītoraifu (Shinchōsha, 1983).

- The central ward of Yokohama city.

- In old-fashioned Romanization, Kudō’s name is spelled KUDOH HIROO.