Abstract: In December 2023, the authors screened the film Plan 75, a dystopic meditation on Japan’s future as an aging society, with a public audience at Princeton University. The essay offers reflections on the experience of watching the film, the nature of Hayakawa Chie’s social commentary and the visual way in which she realizes it, and the present social context for the film’s futuristic meditation. The film won the Caméra d’Or Special Mention Prize at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, and after screenings at global film festivals and the Japan Society of New York, was made available for streaming in the U.S. in late 2023. The film offers contributions to curricula that deal with issues of aging, global capitalism and degrowth, the anthropology and sociology of care, demographic transitions, neoliberal capitalism, and the emergence of a language of individual responsibility in social welfare.

Keywords: Japan’s aging society, anthropology and sociology of care, death, dystopic commentary, demographic burden, welfare society, Hayakawa Chie, Plan 75

Japan is the oldest country in the world and the oldest large society in human history. In the world’s eyes, it has become a laboratory for imagining what such a society might feel like. Once the object of attention for its miraculous growth and industriousness, it has now become terrain for the study of post-growth and the policies that attempt to chart a new course in these yet untested waters. Providing the level of social welfare to which Japanese people have grown accustomed will mean stretching available resources. Hayakawa Chie’s 2022 film (released for streaming in the U.S. in 2023), Plan 75, imagines this scenario through a dystopic, futuristic lens, magnifying and distorting the current social system and the government’s emerging emphasis on self-sufficiency and work in order to reveal its inadequacies and potential dangers.

Plan 75 conceptualizes a dystopic future in which the Japanese government offers citizens age 75 and over the option to be euthanized, cremated, and buried free of charge. The film won the Caméra d’Or Special Mention Prize at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival and received awards at the Thessaloniki Film Festival, as well as at festivals in Japan. Hayakawa also received the Geijutsu senshō shinjin shō, awarded to emerging artists by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs. Plan 75 was Japan’s official submission for the Oscars Best International Feature. It was released for streaming on U.S. platforms in winter 2023. On December 7, 2023, Plan 75 was screened at Princeton University to an audience of students and faculty in East Asian Studies, Sociology, and Anthropology. Comments from audience members, including short reflections offered by Amy Borovoy, Elizabeth Davis, Junko Kitanaka, and Jim Raymo, inspired our collaboration on this short essay.

The storyline of Plan 75 is astonishing, but in moving through its fictional terrain, we are stimulated to imagine the predicaments, vulnerabilities, uncertainties, and crises associated with the extreme longevity of Japanese people today, as well as the financial, physical, and emotional demands of caring for a society with the oldest large population in human history.1 What makes the film particularly provocative is that it directs its social commentary toward the frayed social networks of family and work, the “welfare society” which the government has historically relied on to provide social welfare and social stability to the people. It is “care” itself that constitutes the object of concern in this filmic depiction of a dark future that appears in some ways strikingly close to the society we are familiar with today.

The architecture of the film is cramped, dark, and dank. Mostly, the characters move or dwell or labor inside their homes or workplaces, conveying an atmospheric smallness that emphasizes the isolation and narrow horizons of the characters’ everyday lives. It is not until the final sequence of the film that something like a landscape of the city—a visualization of collective life—can be glimpsed. The very notion of a public, of a Japanese society, takes form only in occasional radio broadcasts announcing the passage of Plan 75 three years before the main action of the film, and, deeper into the film, the possibility of a Plan 65 under discussion by government officials. It is through radio broadcasts, too, that the idea is introduced as common-sense that the rapidly aging population is a drain on the young. This idea arrives in an impersonal, disembodied voice through public announcements that are never verified in the experience of the characters—a voice that hovers in the film as a chimera or specter of society. Hayakawa implies a consensual understanding of the plan’s necessity, although we never witness the government make a case for the plan. That tacit acceptance is itself disturbing. While the plan claims to protect the welfare of the people, the film does little to visualize the community it claims to protect. This absence of a social collectivity (which the government claims to protect) is also a striking feature of the film. Viewers may wonder on behalf of whom, and in the interest of whom, the radio announcements are made. What, the film asks, is this public being served by the euthanasia of the elderly? What is this Japanese society invoked by the first character to speak, a young man who shoots to death a number of elderly people at a care facility, and then himself, after penning a manifesto on the “long, proud history” of Japanese self-sacrifice—a reference to the murder of 19 residents in a nursing home in Sagamihara City in July 2016?

The film is quiet, but not silent. Very little of the two hours is filled with speech or dialogue. In most scenes, the camera follows one or the other of the main characters as they go about their days, mostly alone, lingering in close-ups of their faces. Much is conveyed by their comportment and demeanor that is never put into words; there is a doggedness and inevitability to their actions that suggests resignation. The film slowly settles into several points of view associated with the three main characters: Michi (played by Chieko Baishō, known for her role as Sakura in the long-running film series, Otoko wa Tsurai yo), a 78-year-old woman who works as a cleaner at a hotel at the beginning of the film, and ultimately signs up for Plan 75; Hiromu, a young employee of a private company that recruits and helps elderly people apply to die; and Maria, a young mother and labor migrant from the Philippines who ends up working for the government, stripping the bodies of the euthanized dead.

Image 1. Alessandro Marotta, Plan 75: La Recensione del Film di Chie Hayakawa, May 17, 2023 (Source)

The film attends to the coldness of state care bureaucracy with a keen eye, and Japan’s abundant and outward-facing government infrastructure is a rich target. The scenes of ward offices where Plan 75 is promoted are punctuated by the sounds of announcements, paging systems, and automated elevator voices and bells. A promotional video for Plan 75 plays on a loop on a large television screen in the waiting area where a pair of elderly characters sit for medical checks. We see ubiquitous pamphlets and posters with the blue and orange “Plan 75” logo, in which the “a” and “o” become the eyes on a smiling face (Image 1). Solicitous and earnest young workers promote Plan 75 to elderly clients, using honorific language. They are friendly, and good listeners, and yet each meeting is timed at precisely 30 minutes. In the short version of the film, released in 2018 as part of the omnibus production Ten Years Japan (Hirokazu Koreeda, executive producer), a young worker quickly pulls a ruler out of his pocket to measure the space between the posters he is putting up to advertise the plan at a local train station –a gesture that describes the business of bureaucracy as precise, calculated, and unfeeling.

The distinction between impersonal bureaucracy and heartfelt care is a central theme explored in the film. In interviews, Hayakawa has talked about being troubled by what she describes as “doublespeak” (iikae) in official discourse which appears on the surface as “kind” (shinsetsu) and “positive” (pojitibu) and to provide “security” (anshin). In fact, the film verges on horror as it is revealed that—contrary to the dignified cremation and burial process promised in Plan 75 promotions—the cremated bodies of the euthanized are processed through an industrial waste disposal service (“Landfill Services Inc.”) which recycles materials, ranging from rubber and metal to animal carcasses and cremains, into paper and clothes.

Image 2. David Erlich, “‘Plan 75’ Review: Haunting Japanese Heartbreaker Images a Dystopia That Could Start Any Day Now,” IndieWire, April 19, 2023 (Source)

The meagre warmth offered by the film lies in the friendships among four elderly friends who work as cleaners at a hotel. Their trajectories exemplify the struggle many working-class and even middle-class citizens face to support themselves in old age. After one of the friends collapses at work, the remaining three are laid off; they are told that customers prefer not to have old people working in the hotel (Image 2). Michi, newly isolated from her work-situated friendships, and having no family to take her in, seeks other jobs with great difficulty. She resigns herself to losing her apartment and gives up on a housing program for senior citizens after finding the self-service kiosk closed at the welfare office. Perhaps predictably, her encounters with social services reinforce her willingness to consider Plan 75. When Michi visits the friend who collapsed at work, she finds her long dead at the kitchen table; alone, she had no one to help her.

Hiromu’s long-estranged uncle, whom he reencounters at a soup kitchen where he is recruiting clients for Plan 75, lives alone in a one-room flat without amenities, and donates blood to earn money. The uncle, who never married or had children—“no attachments”—has lived much of his life alone, moving from city to city to work construction jobs. He signs up for Plan 75 on the first day of eligibility, his seventy-fifth birthday. The solitary nature of elderly life and the dehumanization and invisibility of old people are palpable in these storylines.

These scenes evoke the specter of lonely death and disconnection that has received a good deal of attention in the mass media, and Hayakawa gestures at what may be at stake in the deterioration of care.2 The film also addresses the threat of dehumanization of the dead, something anthropologist Anne Allison has explored in her analyses of new forms of memorialization and the “redesign [of] the sociality of managing the dead” (2021: 624; see also 2015: 135). Allison explores shifting organization of the social labor involved in caring for the dead and the technologization, economization, and commoditization of memorial rites through forms of burial which are replacing internment in the family plot at a Buddhist temple (2021).

The visual articulation of work becomes a more focused aspect of the film as Michi and her group of elderly friends are displaced from their jobs and soon lose touch. Meanwhile, the young characters, Hiromu and Maria—along with another (unnamed) character who counsels Michi by phone as she approaches her euthanasia appointment—all find work in the death industry that has grown up around the administration of Plan 75, though they all appear to have significant reservations about the work they are doing. It is difficult to distinguish private service companies from state agencies in this death industry; public-private partnerships pervade the near-future political economy of Plan 75. The film is interested in moments of ambiguous responsibility for the elderly, in which families are failing to provide the care they once were expected to, or estranged family members unexpectedly step in.

Two scenes take place at a small public park where an information booth for Plan 75 is set up alongside a soup kitchen that serves not only elderly people, but also workers and families. These desolate scenes hint at broader poverty, beyond the poor elderly population. They enhance the sense carried by all the characters in the film that jobs are rare and precious things—a sentiment that echoes the cultural ethos of the postwar, high growth era, in which jobs supported the wealth and social livelihood of the people. As income dries up for the aging population and the Japanese economy grows more slowly, we see the darker sides of this system: however hard young people work, they, too, may end up without a home or a source of income in their old age.

Plan 75 also explores the presence of immigrant workers, admitted to Japan to perform labor that Japanese citizens do not want to do while these immigrants struggle to care for their own families back home. One of the main characters, Maria, who immigrated to Japan in order to earn money to pay for her young daughter’s urgent medical care in the Philippines, moves from a job providing support to elderly patients at a private care facility to a government job that pays better. This job also offers her a better vantage point on the economic value and the waste generated by the mass euthanasia of the elderly.

Plan 75’s premise is a shocking one. But perhaps it is less surprising in light of Japan’s demographic past, present, and future. A half a century of below-replacement fertility rates, combined with low mortality and relatively limited immigration, has resulted in Japan becoming the oldest country in the world. The Japanese government is thus contemplating social, economic, and policy responses to this demographic reality in the absence of guiding historical precedent. Soon, this same predicament will be shared by other societies, including Western and Northern European nations and China, and Japan’s successes and failures will surely inform the approaches taken by many other rapidly aging societies in East Asia and Europe.

Demographers often discuss population aging in terms of a simple but rather arbitrary measure: the percent of the population age 65 and above. Currently, nearly one in three Japanese people meets that criterion, and this figure is projected to increase to just under 40% by mid-century. While this simple measure of population aging makes sense, given that 65 is the age of full eligibility for public pension, the percent of the population age 75 and over may be more informative from a social, economic, and policy perspective. Seventy-five is also a somewhat arbitrary age, but it is a well-established epidemiological threshold beyond which the risk of chronic and acute health conditions increases rapidly. Furthermore, it is an age beyond which the risk of widowhood increases—especially for women—with implications for access to family-provided support and care. Currently, 16% of the Japanese population is age 75 or above, and this figure is projected to reach 25% by 2050. Japan is thus not only the oldest population in the world, but it also has the oldest older population in the world.3

Demographic data and policy memos often focus on the shrinking ratio of healthy, working-age citizens: those who earn, invest, and save, and thus support a growing number of elderly retirees with health care needs. It is well known that Japan has one of the world’s longest life expectancies, especially for women, with life expectancy at birth currently calculated to be 81 years for men and 87 years for women.

More relevant for a demographically-informed understanding of Plan 75, however, is life expectancy at age 75—that is, how long, on average, those who reach age 75 can expect to live. For men, that number is 12.5 years, and for women it is 16 years; women who live to age 75 are, on average, expected to live until about 91 years old. The modal age at death (i.e., the age at which the largest number of deaths occur) for the Japanese population as a whole is 88, and for Japanese women it is 92. Older widowed women are among the most economically disadvantaged groups in Japan, and they will be particularly affected by likely future reductions in pension and health care benefits.4 Additionally, 20% of older Japanese now live alone and solo living in later life is expected to increase in the coming years, as cohorts that experienced large increases in divorce reach older ages, and especially as cohorts experiencing the rise in lifelong singlehood and childlessness enter later life.

These trends raise important policy concerns about the public and private capacity to support the well-being of the growing older population. And they are not reversible; in the absence of a massive increase in immigration, the age structure of Japan’s population will continue to change, becoming much older and smaller than it is today. This societal trajectory will be compounded by a shortage of health care workers, shrinking local populations across much of Japan, the aging of family caregivers themselves, and increasing social isolation.5

Yet beneath the specter of mass death explored in the film, there is a subtler, ground-level critique of society, one that concerns the lives of elderly people and not their deaths. This critique is carefully elaborated through the struggles of the elderly characters to achieve dignity by earning a living. This facet of the film is not fictional; it is already a reality that more Japanese retirees must continue working or return to work in late life to support themselves than ever before. Simultaneously, the shrinking population creates a labor shortage. The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare’s web page on “preparing for the era of the 100-year life” (jinsei hyakunen jidai ni mukete) encourages retirees to consider returning to work and offers policies and guidelines for elderly employment, including how to re-train employees over age 65—known as “reskilling” (rekarento kyōiku)—and how to automate the workplace to make it safer for injury-prone elderly workers. In euphemistic language, the webpage endorses “creat[ing] an environment which responds to the hopes of those who want to work and actualizes their abilities” (hataraku iyoku ga aru kata ga kibō ni ōjite sono nōryoku o hakki dekiru kankyō o seibi suru koto).

The short version of Plan 75 includes a female character with dementia whose family is struggling to make caregiving decisions. This plotline captures a parallel national predicament related to anxiety about cognitive decline. The plotline is shaped by media coverage of those with dementia committing seemingly irrational acts, such as wandering onto railroad tracks or driving in reverse on highways (Kitanaka 2020: 121). Such representations of a dementia crisis in Japan have produced “prevention hype:” as the brain becomes a new project of the self that one is expected to monitor, manage, and enhance, the very pursuit of health has brought a new kind of obsession with a “healthy brain” as the center of one’s personhood and the definition of a good life, particularly in old age. As pseudoscientific prevention measures for dementia flourish on TV and social media, medical experts worry about how lay people are exercising their bodies and brains without really knowing if they will develop dementia, or when it will set in. In Japan, the number of people afflicted with dementia exceeds six million and those with MCI (mild cognitive impairment) number roughly five million.6

Plan 75 captures in dramatic form what Kitanaka (2020, 2021) has observed: Japanese people continue to oscillate between a desire to accept the vulnerabilities associated with aging and a need to turn away from or even eradicate them. Concerns about vulnerability attained a special sense of urgency during the Covid pandemic, as dementia tōjishas (those who experience dementia) and experts experienced the difficulty of caring for people with dementia during a state of emergency. Their concerns may be reaching a more receptive audience than before the pandemic, which shattered the illusion of control in health and of the power of prevention.

The future represented in Plan 75 describes, in some sense, the ultimate form of preventing dementia: preventing aging itself. Chie Hayakawa has spoken of a fear that was commonly expressed by elderly people she interviewed: the fear of “being a burden” (meiwaku o kakeru) in a society that regards as shameful any dependency on others for social welfare. In interviews concerning her motivations in making the film, Hayakawa has worried that Japan is becoming a society in which asking for help is unacceptable, where “individual responsibility” (jiko sekinin) has become a buzzword, and where the dignity of the elderly and all humans (hito no songen) is threatened. Once, a “long life” (nagaiki) was considered something to celebrate (omedetai koto), but it is increasingly characterized as “negative” and a source of continual worry.7

The “apocalyptic demography” to which Hayakawa traces these cultural trends has become a regular feature of mass media discourse in Japan. Yale University economist Narita Yūsuke created shock waves and drew hundreds of thousands of followers to his X account when, as a guest on an online news show, he suggested that the solution to Japan’s aging society was “mass suicide” of the elderly (shūdan jiketsu, shūdan seppuku). Narita went on to explain that he did not mean “biological” (butsuriteki) suicide but rather “social” suicide, meaning that those who were no longer vital to society should step aside and let others fill in.8 But the statement nonetheless went viral. Hayakawa has also mentioned the influence of the July 2016 stabbing of 19 nursing home residents committed by 26-year-old Satoshi Uematsu, alluded to in the opening sequence of the film. Uematsu had previously written a letter to his political representative arguing for the euthanasia of disabled people who were unable to carry out basic functions.

These sensational pronouncements and extreme acts draw attention not because they are common or reflect mainstream viewpoints, but because they give expression to underlying fears and concerns that are informed by real phenomena.

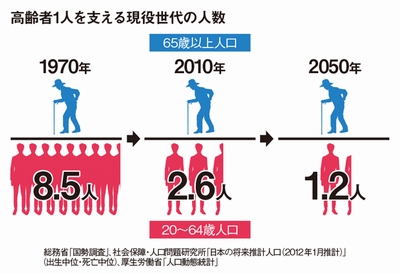

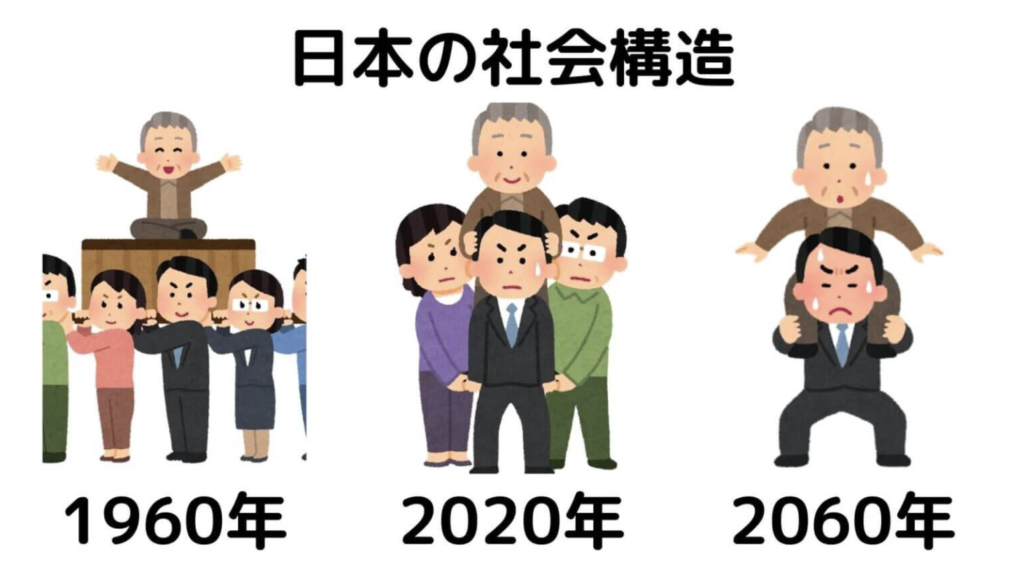

Image 3 (Source)

Image 4 (Source)

The demographic trends that provide the backdrop for Plan 75 are not reversible. The extreme longevity of the Japanese people will make it difficult, if not impossible, to maintain current levels of social welfare for the population, while the working-age population supporting these systems with their taxes shrinks. The burdens of caring for an aging society will be shouldered by fewer and fewer people. This growing “burden of care” on every individual is frequently visualized in policy and government documents and educational materials for the young (Images 3 and 4). Plan 75’s dystopian lens reflects these emerging uncertainties, a decline in gross domestic output and labor power, and an overwhelming and onerous demand for care.

At the same time, as viewers making sense of the film, we must keep in mind other realities. The top-heavy population pyramid that now poses a social burden is itself the result of Japan’s high quality of life, excellent health care, and relative social equality compared with many other societies, including the U.S. Japanese society is known to have comparatively good health at older ages, continuing work and social engagement beyond the typical retirement age, excellent public health care, and family provision of instrumental, emotional, and physical care for even frail, older adults. It is also one of a handful of countries that has long term care insurance through which the costs of elderly care are subsidized by the young and healthy. Citizens aged 40 years and over must pay premiums. Japan largely kept its elderly population safe during the coronavirus pandemic because of skilled care and rigorous protocols (Estévez-Abe and Hirō 2021).

Following our screening of Plan 75 at Princeton, a colleague who studies downwardly mobile populations in the United States expressed surprise at the alarmist tone of the film. Long life expectancies are, after all, an indicator of a healthy society. By contrast, in the U.S., life expectancy is declining among some demographic groups due to factors including substance abuse, gun violence, suicide, and the opioid epidemic—realities that tell their own dystopic story.9

Plan 75 adopts the premise of mass euthanasia as a provocation. It depicts a rather clichéd representation of a cold and controlling government bureaucracy that communicates in Orwellian doublespeak, obscuring the economic and political motives driving its operations. In doing so, however, the film offers us a starting point to explore the very real challenges of Japan’s unprecedented demographic situation, and to ask deeper, subtler questions about dehumanization in the context of an irreversibly collapsing welfare society and overwhelming demands on the individual.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Mana Winters for helping to organize the public screening of the film at Princeton University and Tae Cimarosti, Sheldon Garon, and Carolyn Rouse for thought-provoking conversations after the screening. Kitanaka’s research has been funded by Kakenhi JP21H05174.

References

Allison, Anne. 2015. “Discounted Life: Social Time in Relationless Japan.” Boundary 2. 42.3 (2015): 129–141.

Allison, Anne. 2021. “Automated graves: The precarity and prosthetics of caring for the dead in Japan.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 24(4): 622–636.

Case, Anne and Angus Deaton. 2015. “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife Among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), November 2, 112 (49): 15078-15083.

Estévez-Abe Margarita and Hirō. 2021. “COVID-19 and Long-Term Care Policy for Older People in Japan.” Journal of Aging and Social Policy. Jul–Oct; 33(4-5): 444–458.

Jones, Randall S. 2023. “The Japanese Economy: Strategies to Cope with a Shrinking and Aging Population. Presented at Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry.” February 1. https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/events/bbl/23020101.html

Kitanaka, Junko. 2020. “In the Mind of Dementia: Neurobiological Empathy, Incommensurability, and the Dementia Tōjisha Movement in Japan.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34(1): 119–135.

Kitanaka, Junko. 2021. “Limits of empathy: The Dementia Tōjisha Movement in Japan.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 57(3): 266–272.

Maruyama, Katsura. 2016. “New Perspectives on Women and the Pension System: Coping with Family Care and Extending Social Insurance to Part-time Workers.” [Josei to nenkin mondai no arata na shoten: Kazoku kea e no hairyo to tekiyō kakudai mondai.] Social Security Research [Shakai hoshō kenkyū]1(2): 323–338.

Ogawa, Naohiro. “Population Aging and Policy Options for a Sustainable Future: The Case of Japan.” Genus (July–December 2005) Vol. 61, No. 3/4: 369–410. Published by Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza.”

United Nations (2022) World Population Prospects, 2022 Revision. https://population.un.org/wpp/

Interviews with Hayakawa Chie

Imagining a World in Which Those who Turn 75 Must Choose Between Life and Death, An Interview with Plan 75 Director Chie Hayakawa [75 ni nattara seishi o erabu shakai egaita eiga, Plan 75, Hayakawa Chie kantoku intabyū], Teretō BIZ, May 24, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZF-zYEspOU&ab_channel=%E3%83%86%E3%83%AC%E6%9D%B1BIZ (See FN 3)

For a More Tolerant World, Hayakawa Chie/Film Director, NHK World, Broadcast August 15, 2022. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/shows/2058940/ (See FN 4)

Interview with Director Chie Hayakawa, Mubisute, December 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G_Mhe1nDt-g&ab_channel=%E3%83%A0%E3%83%93%E3%82%B9%E3%83%86%EF%BC%81YOUTUBE (See FN 4)

Movies are Love! Special Films, interview with Director Hayakawa Chie. [Eiga wa mana yo! Tokubetsu Eiga, Plan 75, Hayakawa Chie kantoku intabyū.] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCbfSg1pJzQ&ab_channel=otocoto (See FN 4)

- See, for example, Ogawa, Naohiro. “Population Aging and Policy Options for a Sustainable Future: The Case of Japan.” Genus; July – December 2005, Vol. 61, No. 3/4, pp. 369–410 Published by: Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza.”

- The Japanese media reports closely on the phenomenon of elderly living alone dying at home unaccompanied. NHK reports that between January-March of 202k4, 17,000 elderly aged 65 and over died alone at home. Based on this, the report suggests that the annual number could reach 68,000. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20240513/k10014448181000.html; The Cabinet Office also has a working group collecting data and making policy on the issue of solitary death: https://www.cao.go.jp/kodoku_koritsu/torikumi/wg/dai4/pdf/gijiyousi.pdf; The story has also gained attention in the U.S. mass media. See particularly, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/30/world/asia/japan-lonely-deaths-the-end.html

- United Nations (2022) World Population Prospects, 2022 Revision. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- See for example: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/events/bbl/23020101.html and https://www.ipss.go.jp/syoushika/bunken/data/pdf/sh20212204.pdf

- Japan has long been characterized as a familistic welfare state, but support from families is becoming more difficult to maintain as intergenerational co-residence declines rapidly. About 80% of older Japanese co-resided with an adult child in 1970, but this figure is now a bit less than half of that.

- In 2017, the Japanese government implemented mandatory dementia screening for anyone over seventy-five renewing a driver’s license. Large-scale corporations provide brain MRI to their employees as an additional option for annual health checkups which has resulted in more workers coming to memory clinics.

- See, for example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZF-zYEspOU&ab_channel=%E3%83%86%E3%83%AC%E6%9D%B1BIZ; https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/shows/2058940/; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G_Mhe1nDt-g&ab_channel=%E3%83%A0%E3%83%93%E3%82%B9%E3%83%86%EF%BC%81YOUTUBE; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCbfSg1pJzQ&ab_channel=otocoto

- ABEMA Prime, Dec. 19, 2021 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wgy7pS3-7sc&ab_channel=ABEMAPrime%23%E3%82%A2%E3%83%99%E3%83%97%E3%83%A9%E3%80%90%E5%85%AC%E5%BC%8F%E3%80%91

- See, for example, Anne Case an Angus Deaton, “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife Among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), November 2, 2015,112 (49) 15078-15083.