Abstract: This article explores popular music of Japan’s Cold War era, with a special focus on singing duo The Peanuts and the film Mothra. It argues that Japanese culture of the Cold War must be understood as participating simultaneously in all three networks of the Cold War order—the First World of capitalist liberal democracies, the Second World of the socialist bloc, and the Third World of the decolonizing and nonaligned Bandung Movement.

Keywords: Popular music, Indonesia, Bandung Movement, Afro-Caribbean music, Hotta Yoshie, Koseki Yūji

Existing cultural histories of Japan’s Cold War era tend to focus, for good reason, on the Japan-U.S. relationship—on, that is, Japan’s role as part of what was called the First World of capitalist, liberal democracies.1 But this tendency has the side effect of effacing the active participation by Japanese cultural producers in the other two worlds of the Cold War order—the Second World of the socialist bloc and the Third World of the decolonizing and nonaligned Bandung movement. The Japan Socialist Party and the Japan Communist Party were, after all, active participants in Japanese politics and culture throughout the Cold War era and maintained close contacts with their counterparts abroad. Furthermore, Japan was one of 29 countries to send official delegations to the 1955 Bandung Asian-African Conference in Indonesia—a newly independent nation that just a decade earlier had been under Japanese occupation. After the 1955 conference, the Japanese government maintained an on-again, off-again relation to the Bandung movement. For example, it maintained close ties with Indonesia throughout the Cold War, making it the largest single recipient of Japanese overseas aid during the period (Miyagi, 2017: 35-47). But the government sought to orient Japan primarily as a member of the First World circuit, stressing its participation in venues such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which Japan signed in 1955, and the United Nations, to which Japan was admitted in 1956.

However, while the Japanese state backed away from the Bandung Movement, ordinary Japanese citizens—in particular, cultural producers and intellectuals on the political left, but also those involved in producing mainstream popular culture—were less ambivalent. They tended to identify powerfully with Bandung, hoping to build a Japan that was nonaligned and supportive of decolonization efforts in the region. Japanese writers and critics, for example, regularly participated in meetings of the Afro-Asian Writers Association (AAWA), the primary cultural arm of the Bandung Movement and engaged in the forms of thought it produced.2 As recent scholarship has shown, the massive 1960 popular uprising against Anpo, the revised US-Japan Security Treaty, was as much driven by the desire for a nonaligned Japan as it was by anti-American sentiment (Kapur 2018, 13). In other words, a significant part of Cold War Japanese culture included an aspiration for Japan to function as a Third World ally of the decolonizing and nonaligned movements.

This view of Japan was shared by many outside of the country, as well. AAWA, for example, held an Emergency Meeting in Tokyo in January 1961, largely in response to the Anpo demonstrations. Participants in that Tokyo meeting, both from Japan and elsewhere in Asia and Africa, clearly understood the anti-Anpo protests in 1960 Japan as forming one leg of the anticolonial Bandung movement. We see this, for example, in the poet Nakano Shigeharu’s welcoming remarks:

Last year alone, in Africa, seventeen new independent nations were born, and in April of this year, Sierra Leone is supposed to obtain its independence. Victory for the people of Algeria is surely near, as well. The changes and developments in Asia have been no less striking. They include the revolutionary uprising by the people of South Korea and the great struggle of the Japanese people in opposition to the U.S.-Japan Military alliance (Japanese Liaison Committee of Afro-Asian Writers, 1961: 30. Bourdaghs translation).

This vision of a Third World Japan involved a complex, sometimes contradictory relationship to Japan’s own recent past as an imperial power. From the start, Japan’s participation in Bandung was problematic: as a former empire rather than colony, it was—in the words of historian Kweku Ampiah—something like a cat attending a mice convention.3 A Third World Japan could be understood as a renunciation of Japan’s imperial project—but also as its continuation, as well as a dodge aimed at repressing any memory of that past.

I should note that many have previously criticized the terminology of the Three Worlds as both imprecise (in which world, for example, does the People’s Republic of China belong?) and as ideologically problematic. The term “Third World” in particular has been widely criticized, with many preferring to replace it with other terms such as Global South. Let me acknowledge those critiques even as I continue to use the terminology of “Three Worlds” here, both because that was the language that many of the figures discussed herein used during what Michael Denning has termed “The Age of the Three Worlds,” and because I want to think about the concept of a world in a more phenomenological sense of worlding: to think of worlding as a verb more than world as a noun.4 I think this fluid notion of worlding, which includes both spatial and temporal flux, helps us arrive at a more productive understanding of what Japanese Cold War cultural figures were up to as they tried to re-define Japan’s position in relation to the multiple circuits of Cold War culture and politics.

In sum, a dense complexity characterized Cold War’s Japan’s connections to the transnational networks that dominated the era. The present article revisits mainstream Japanese popular music from the era and traces its connections to all Three Worlds of the Cold War era. I focus primarily on The Peanuts, a remarkably popular duo that dominated Japanese hit charts from their debut in 1959 until their retirement from show business in 1975. Their career provides an apt instance of the ways in which Japanese culture of the Cold War participated in the various networks of the Cold War order and provides a window on the complex web of historical remembering and forgetting that this entailed.

The Peanuts and the 1960s Cover Song Boom

The musical soundscape of 1950s and 60s Japan was replete with cover versions of numbers that had been hits elsewhere—including songs from all Three Worlds of the Cold War—and The Peanuts were one of the most successful and prolific producers of cover versions during the era.5 As one might expect, given the importance of U.S.-Japan relations, Japanese popular music charts often included localized versions of American hit songs, with lyrics partially or wholly translated into Japanese. Likewise, the boom in utagoe (‘singing voice’) choral singing—in both formal chorus groups affiliated with the Japan Communist Party and informal utagoe coffee shops that sprung up around the country in the late 1950s and early 1960s—brought a wide repertoire of Soviet and other Second World songs into the fabric of everyday life in Japan.6 Japanese music fans also participated in a series of proto-world music booms—the rumba, mambo, cha-cha-cha, samba, bossa nova, calypso, and many others—that linked Japanese performers to the decolonizing Third World in Africa, Asia, and the Americas (Wajima, 2015).

The Peanuts was a singing duo comprised of twin sisters, Itō Emi (1941-2012) and Itō Yumi (1941-2016). Managed by Watanabe Productions (a major force in Japanese popular music that had its origins as a supplier of performers for clubs located around U.S. military bases), they debuted in 1959 at age eighteen. With their striking sibling harmonies, the twin sisters soon became regulars on the local pop music hit charts. Before they retired from show business in 1975, The Peanuts released eighty singles and fifty LPs, selling over ten million records along the way (Noji, 2010: 18). They made numerous film appearances, as we will see below, but were more closely associated with the new medium of television, most notably through their role as co-hosts of the musical variety program Soap Bubble Holiday (Shabon dama horidei), which aired Sunday evenings on the NTV network from 1961 to 1972.7 Japanese television broadcasting began in 1953, with the national audience for the new medium expanding exponentially during the early years of The Peanuts’ career. Two televised spectacles accelerated the growth of the new medium: the 1959 royal wedding of Crown Prince Akihito to commoner Shōda Michiko and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics—the latter broadcast in color. By 1962 more than half of the households in Japan owned a television set, and by 1964 that percentage would hit 95%. Within a few years the saturation would exceed 100%: there were more television receivers in Japan than households (Kim, 2017: 16; Steinberg, 2012: 10). The Peanuts were, at least according to some observers, a factor in that growth. “As for the field of Japanese television,” a weekly tabloid would claim in 1965, “it is no exaggeration to say that it was thanks to The Peanuts that it developed so rapidly in one direction.”8

As fixtures of the increasingly media-saturated everyday life of 1960s Japan, The Peanuts became a virtual presence in almost every household in the land. They were also prototypes for a new kind of popular music idol: recruited by Watanabe Productions as teenage amateurs, prior to their debut the agency subjected them to a rigorous training course in singing, dancing, and public relations.9 As both Emi and Yumi would acknowledge in interviews after their retirement, they were very much manufactured idols (Noji, 2010: 19). Their performing and recording repertoire was carefully selected for them by their handlers, in particular Watanabe Misa, their agency’s female vice president, and Miyagawa Hiroshi, a pianist and arranger under contract to Watanabe Productions. It was Miyagawa who first discovered the twins performing in a Nagoya nightclub and arranged to have them signed by the agency. He would go on to produce and arrange their recordings, as well as compose many of the duo’s signature numbers.

When we look at the numbers that Miyagawa and his colleagues chose for The Peanuts, the first thing that strikes us is the remarkable cosmopolitanism of the selection. In terms of musical repertoire and style, we can discover links between The Peanuts and all Three Worlds of the Cold War era. Most obvious, not surprisingly, are the ties they draw to the First World of capitalist, liberal democracies. The Peanuts’ repertoire consisted largely of easy-listening mainstream pop songs, including many translated cover versions of Anglo-American hits. In this, they provided something like a sonic enactment of the key Cold War intellectual framework known as modernization theory. Modernization theory was a model developed under Cold War social sciences that positioned Japan and other nonwestern American allies as pursuing a developmentalist path, in which they were said to be advancing toward ‘modernity’ (defined as being the contemporary situation of the U.S.), but always at a time lag and always sidestepping the need for violent historical change. The theory offered an imaginary road map for the peaceful (read: non-Marxist) transformation of developing societies. 1958, the year The Peanuts signed to Watanabe Productions, was also the year of the first “Conference on Modern Japan,” a series that brought together North American, European, and Japanese academics first at the University of Michigan and later at Hakone, Japan (1960) and Bermuda (1962), to create what became an enormously influential scholarly definition of “modernization” in Japan.10

Cover versions, with their appearance at some delay from the original version and with their respectful admiration of that original, provided a striking enactment of the modernization theory model. When The Peanuts performed, for example, “Lover, Come Back to Me” or “Stardust” in English, they were playing the part of faithful daughters of American culture following in the footsteps of their U.S. predecessors. It was this stance of loyal imitation, no doubt, that earned The Peanuts their 1966 bookings to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show and The Danny Kaye Show in the U.S. These appearances were widely reported in Japan, intensifying the linkage between Japanese and American popular music worlds—including worried reports about the degree to which the Itō sisters were really mastering English.11 It seemed to many at the time that The Peanuts would likely become the second Japanese popular music act to score a hit in North America and Western Europe, following the unexpected success of Sakamoto Kyū’s “Sukiyaki” (Ue o muite arukō) in 1963.12

While the act of covering implies worshipful reverence for a certain ‘original’ recording, it also simultaneously amounts to an act of appropriation. As the postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha, anthropologist Michael Taussig, and others have argued, in a colonial setting the act of mimicry is double-edged: when the colonized person mimics the colonizer, the performance simultaneously signals both respect (‘I wish I could be like you’) and potential displacement (‘I can be just like you’)(Bhabha, 1984; Taussig, 1993). We see a similar ambiguity in The Peanuts’ Anglo-American repertoire. A 1960 review of the duo’s success in Music Life magazine identified the secret of their remarkable success not with their ability to produce letter-perfect imitations, but rather with their “unique individuality,” which gave them the ability to alter existing songs and make numbers their own:

Able to retain steady popularity in the fiercely competitive entertainment world where new talents appear one after the other, the charm of The Peanuts lies not in their ability to express accurately the character that exists in the song itself, but rather in the way they produce deeply satisfying works that draw out something different in the song, bringing to it a fresh sound and distinct individuality that arises from their blessing of rich talent.13

The 1970 album Feeling Good: The Peanuts’ New World, for example, featured covers of such recent hits as “What the World Needs Now,” “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,” “Michelle,” “The Look of Love,” and “I Say a Little Prayer.” They keep the lyrics entirely in English, a sign of faithful covering. But Miyagawa and the Itō sisters actively rework each of the cover songs on the record. As we listen we quickly recognize the original, but much of the pleasure these versions produce comes from the degree to which they transform those originals—the mambo rhythm overlaid onto “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head,” for example, or the baroque organ flourish at the opening of “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” or again the jazzy wire-brush drumming foregrounded on “This Girl’s in Love with You.” On many of these arrangements, the vocal parts are rewritten to foreground The Peanuts’ signature sibling harmony. Typically, their two voices start a passage by overlapping on the same notes, then diverge slightly to generate musical tension, only to resolve back to a satisfying perfect unison. Miyagawa’s velvety orchestral arrangements purr with sophistication, often featuring syncopated Afro-Caribbean rhythms, striking instrumental fills and new hooks not found on the original recordings. In other words, even as these Japanese covers of American and British pop songs seem to pledge allegiance to the originals, they also simultaneously demonstrate a pronounced degree of independence that opens up a distance through the act of covering. These covers go beyond subservience to the original, producing something beyond simple imitation.

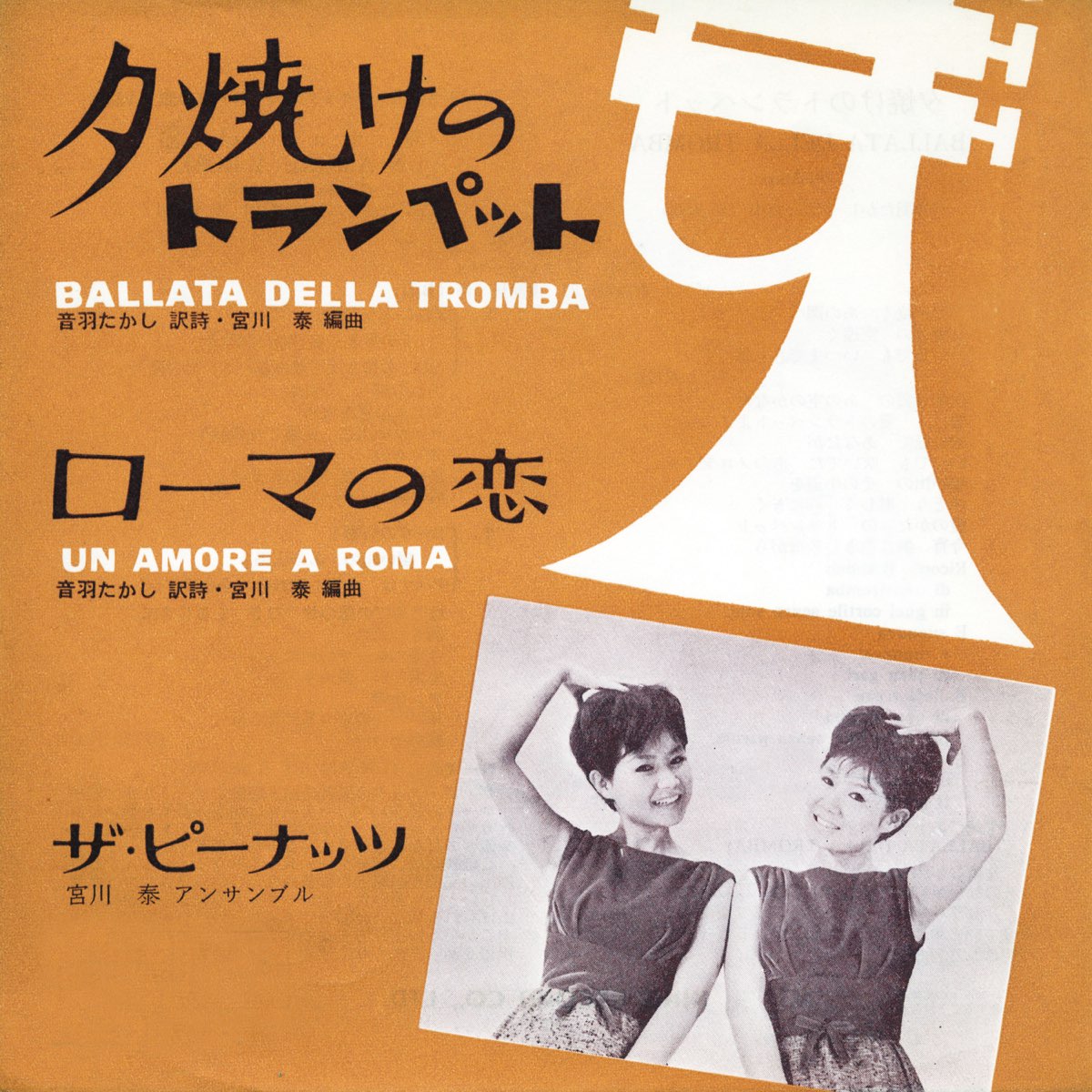

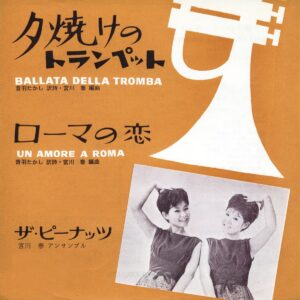

Moreover, even as they frequently covered Anglo-American hit songs, The Peanuts cultivated a First World image more closely connected to continental Europe, especially France, West Germany, and Italy. As one Japanese music critic notes, “More than American Pops, The Peanuts should be considered European/Latin music” (Onzō, 2001: 58). The Peanuts recorded many cover versions of French, Italian, and German pop songs, often singing lyrics at least partially in the original language. Even the original numbers composed specifically for them by Japanese songwriters frequently conveyed, both in lyrics and in music, a continental flair: they were meant to sound like covers of European hits. The duo’s album titles also referred to Europe, including their 1971 album The Glorious Sound of Frances Lai, a tribute to the French chanson composer, and their 1965 album Hits Parade Vol. 6: Around the Europe. On their 45 rpm single record jackets, it was common for song titles to appear in both Japanese and a (non-English) European language, whether the songs were cover versions of foreign numbers or original Japanese compositions. (Fig. 1). Tellingly, one of their biggest hits actually flopped when it was first released in 1963 under the Japanese title “Tōkyō tasogare” (Tokyo Evening). The Peanuts re-rerecorded the Miyagawa Hiroshi composition in a new arrangement the following year, now rebranded as “Un Sera di Tokio.” Under that Italian title, the song became one of the biggest selling singles of 1964, winning both the Best Lyrics and Best Composition honors at that year’s Japan Record Awards.

Fig. 1: Jacket covers of various 45 rpm singles released by The Peanuts

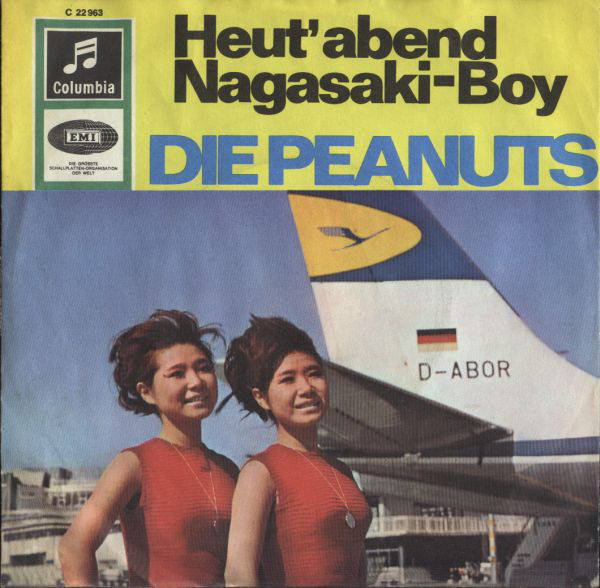

The Peanuts’ ties to Western Europe went beyond simple cover songs and linguistic citations. The duo frequently visited Europe to perform concerts, appear on television, and to undertake recording sessions.14 They formed collaborative relations with a number of European musicians, most notably the Italian-French singer Caterina Valente.15 The Peanuts released recordings on the continental market and apparently reached a fair degree of popularity, especially in West Germany and Italy, where they performed live and starred in television specials. They aimed their 1965 recording “Heut’ Abend” (released under the moniker Die Peanuts) at the West German market, mixing Japanese and German lyrics in a playful manner that embodied the fluid cosmopolitanism of their image. A 1965 Japanese magazine article reported that Watanabe Productions intended the duo to become global stars like film actor Mifune Toshirō and described their domestic fans as feeling a bit like Spencer Tracy in Father of the Bride, watching their little girls grow up and leave home.16

One of the best-known numbers by The Peanuts is their 1963 smash hit, “Koi no vakansu (Vacance de l’amour).” Built around an attractive riff that echoes continental Romani music, the melody employs a harmonic minor scale that at key moments shifts to natural and melodic minor scales, showing off the sisters’ remarkable chorus singing. The single won yet another Japan Record Award for its composer, Miyagawa. The evocative lyrics by Iwatani Tokiko are in Japanese, except for the keyword vacance (French for “vacation”) from the title, which also appears in the chorus refrain.17 The popularity of the song helped vacance become a kind of buzzword in 1960s Japan. No doubt this had something to do with then-current trends in fashion, film, and other domains in which France enjoyed a privileged status. Adding a French veneer to The Peanuts’ sound helped generate a stylish image, one reinforced by the striking fashions—usually, matching outfits—that the duo wore on stage and television. The duo began helping design their own stage costumes from around 1961 and by 1968 were contributing stage wear ideas to other acts as well.18 As one scholar of Japanese fashion history notes, The Peanuts were crucial figures in the rise of a new Paris-centric, upper-middle-class female look in early 1960s Japan (Furmanovsky, 2012).

This air of cosmopolitan sophistication clearly sold well on the market: it was a kind of commodity branding. But The Peanuts’ au courant stylishness also carried overtones that hinted at social and political significance: it was modeling an ideal relationship between Japan and the rest of the First World that involved something more than merely mimicking American hit charts. Part of the reason The Peanuts’ records achieved such popularity is that they spoke to real desires that existed in Japan for a continental lifestyle, one associated with luxury brands and stylish consumption—Paris! Rome! Berlin!—but also with relative autonomy under the Cold War global order. The desirability of mimicking French pop stylings seems in part linked up with a desire to imagine a Japan more like France, a Japan that occupied a less subservient role vis-à-vis the United States in global geopolitics. In 1966, when The Peanuts were at the zenith of their popularity, France withdrew its armed forces from NATO, re-asserting its independent sovereignty and complicating Cold War polarities. In other words, The Peanuts’ European-tinged numbers opened up possibilities for imagining a cosmopolitan Japan on a different historical trajectory—a First World Japan that was something more than just a client state of the U.S.19

Beyond the First World

Oddly enough, “Vacance de l’amour” was also the song that ended up laying down a direct link between The Peanuts and the Second World of the socialist bloc. After The Peanuts’ initial success with their recording of “Vacance de l’amour” in Japan, the song began to circulate beyond the archipelago. A 1963 cover version by Caterina Valente enjoyed some success in both Japan and Europe. Two years later, an even more surprising cover version would appear. Vladimar Tvestov, a foreign correspondent for Soviet state television and radio, took a liking to the number during his stint in Tokyo. He featured the recording in his reports from Japan, and when he returned to Moscow, he introduced The Peanuts’ hit to his media business colleagues there. In 1965 Nina Panteleeva, a prominent singer since the 1940s who had visited Japan in 1961 to perform at a Soviet trade fair, released a Russian-language cover version of the song, and it quickly became a massive hit. “Vacance de l’amour” would eventually become a kind of standard number in the Soviet Union, with many people supposedly not knowing that it was originally a Japanese song. A different version of the song, for example, was featured in the 1967 film, Nezhnost’ (Tenderness, dir. Elyor Ishmukhamedov), a coming-of-age story set in Uzbekistan. Panteleeva would also record a Russian-language cover of The Peanuts’ 1964 hit “Una Sera di Tokio” (Yamanouchi, 2002: 60-63). Finally, The Peanuts themselves traveled to Moscow in April 1967 as members of an official Japanese exchange delegation to the Soviet Union, performing the numbers for their unexpected new audience in the Second World.20

The network linking The Peanuts to the Third World comprises an even denser tangle of connections. Prior to signing with Watanabe Productions, their nightclub act already leaned heavily to Afro-Caribbean sounds, featuring such numbers as “Miami Beach Rhumba,” “Jamaica Farewell,” and “Island in the Sun” (Take, 1999: 75). In their subsequent recording career, the duo would release many cover versions of South American, Central American, and Caribbean popular hits. The B-side of their 1959 debut single was “El Manisero” (“The Peanut Vendor”), the Cuban son number composed by Moisés Simons that ignited the global rumba craze in the 1940s.

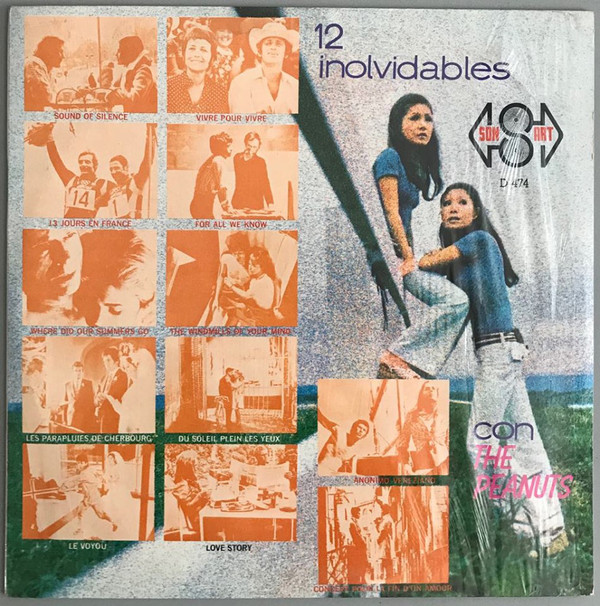

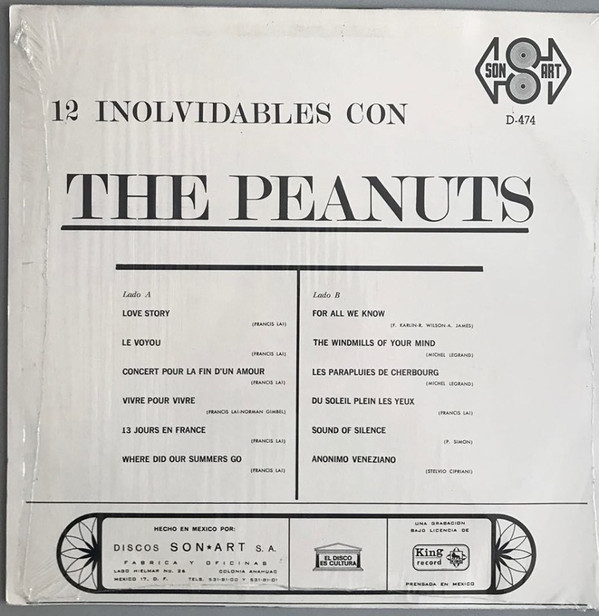

Likewise, their 1959 debut LP included several ‘Latin’ numbers, including “Aru koi no monogatari,” a cover version of the bolero “Historia de un amor” by Panamanian composer Carlos Eleta Almarán, a song that achieved global popularity thanks largely to a 1956 Mexican film of the same title. In The Peanuts’ cover version, the lyrics alternate between Japanese translations and the original Spanish lyrics, a practice they would follow in many of their covers. During their career they released recordings of, among many others, “Quizás, quizás, quizás” (Cuba, better known in English as “Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps”), “La Novia” (Chile), “Magica Luna” (Cuba), “Moliendo Café” (Venezuela), and “¿Quién será?” (Mexico). With their 1961 cover of “Sucu Sucu” (Bolivia), they became one of the first Japanese recording artists to latch onto the rising Sucu Sucu dance craze—in an interview at the time, they reported that they found the style easy both to sing and dance.21 In the 1968 film Mexican Free-for-All (Crazy Cats Mexican daisakusen, dir. Tsuboshima Takashi), a vehicle for fellow Watanabe Productions act The Crazy Cats that was shot partially on location in Mexico, they performed “Cielito Lindo” as part of a musical revue sequence (albeit shot on a soundstage in Japan). They also covered Brazilian numbers, including “Mas, que Nada!,” a 1966 global hit for Sérgio Mendes and Brasil ’66, and “Inori kumikyoku,” a medley of recent bossa nova hits, including “Laia Ladaia” and “The Girl from Ipanema.” The Peanuts’ affection for Latin music was to some degree returned: at least one LP compilation of their hits was released in Mexico (Fig. 3).22

Fig. 3: 12 Inolvidables con The Peanuts (Mexico, Son-Art – D – 474, 1972)

These covers were in part a legacy of the early twentieth century “noise uprising” that cultural historian Michael Denning has described: a global wave of new vernacular musics such as samba, calypso, and jazz that arose in the 1920s and 30s as a product of new electrical recording technologies and launched a ‘decolonization of the ear,’ helping to clear a path for the political decolonization movements that would erupt a few decades later during the Cold War proper (Denning, 2015).

At the same time, however, this fascination for Third World sounds comprises yet another facet of The Peanuts’ First World cosmopolitanism. They were, that is, mirroring the exoticism that characterized much popular music in North American and Western Europe during the 1950s and 60s, taking up in Japan a role played elsewhere by the likes of Martin Denny, Herb Alpert, Les Baxter and other popularizers of ‘exotic’ sounds (Hosokawa, 1999: 72-93). When mambo and other Caribbean and South American dance music genres were first introduced into Japan in the mid-1950s, they were originally presented not so much as Caribbean or South American, but rather as the latest trend in North American pop music (Wajima, 2015: 48-68). Hollywood films such as Underwater! (1955; dir. John Sturges), featuring “King of the Mambo” Perez Prado, were primary vehicles for the Asian circulation of such musical genres, which arrived large stripped of the historical contexts that defined the genres in their original homes (Jones, 2020: 40-42). Japan’s mambo craze was duly covered in the American press, with Time magazine reporting in 1955 that “Tea parlors, coffee shops and bars dispensed their drinks to a rolling mambo beat, and new dance halls were abuilding to cope with the craze.”23 To cover Afro-Caribbean rhythms in 1950 and 60s Tokyo was, in other words, another way to participate in the cosmopolitan lifestyle of places like New York, Paris, and Rome. It was also a continuation of a long history of musical exoticism that characterized the Japanese wartime empire, as I will discuss again below.24

And yet it is also true that when these exotic sounds circulated to Japan, they picked up another set of meanings that resonated locally with different histories and emotions. In doing so, they became part of the self-image of a Japan that liked to see itself as a participant in the Bandung spirit—both because of and despite its history as a colonizer in the Pacific and Asia. We can see this in a striking manner when we trace through the connection between The Peanuts and another popular culture sensation of the Cold War era: a movie monster that played a key role in sustaining the vision of a Third World Japan.

“Mothra’s Song” as Japanese Anthem of the Bandung Movement

Outside of Japan, The Peanuts are best remembered for their role in the Mothra series of kaijū (monster) movies produced by Tōhō Studio. They appeared in the first three titles from the series: Mothra (Mosura, 1961), Mothra vs. Godzilla (Mosura tai Gojira, 1964), and Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (Sandai Kaijū: Chikyū Saidai no Kessen, 1964), all directed by Honda Ishirō and with special effects supervised by the legendary Tsuburaya Eiji. The Peanuts play the shōbijin, a pair of tiny fairy-like creatures from Infant, a fictional South Pacific island that is also home to Mothra, a gigantic moth that serves as local deity and guardian of the island’s residents.

Mothra followed on the international success that Tōhō enjoyed with Godzilla (Gojira, 1954). The studio had huge ambitions for the new film, hoping it would open the kaijū genre to a wider audience both at home and abroad. Their strategy included bringing in a stronger comic element—and also foregrounding song-and-dance sequences that make the film at times seem almost like a musical. The 1961 film that launched the Mothra series was the first kaijū movie shot in full-color Tōhō-scope, the studio’s spectacular widescreen format. The production boasted a then-enormous budget of two hundred million yen (in part supplied by Hollywood: the film was a co-production with Columbia Pictures) and featured a glamorous all-star cast, including The Peanuts (Ono, 2007: 7-10). It was also the first Japanese feature film to boast a four-channel “perfect stereophonic” soundtrack (Kobayashi, 2001-2002: 1:236-7).

In the 1961 film, the shōbijin are kidnapped from Infant Island by the villainous Nelson (Jerry Itō), an unscrupulous show business promoter. He forces them to appear on stage in Tokyo as a kind of sideshow attraction—an unmistakable echo from the 1933 American film King Kong that helped inspire the kaijū genre. In their first Tokyo stage performance, the fairies sing a peculiar number, “Mothra’s Song” (Mosura no uta, discussed in detail below), to summon the monster-deity to come rescue them. In response, Mothra’s egg hatches on Infant Island, its larval form crosses the Pacific Ocean (oblivious to fighter jets that attack it) and ultimately reaches Japan’s capital city, leaving behind a wake of destruction. Mothra then weaves its pupa around a new symbol of Japan’s modernity, Tokyo Tower (opened in 1958), which snaps under the weight. After a gigantic adult moth emerges from the cocoon, it once more crosses the Pacific, in hot pursuit of the unscrupulous Nelson, who has absconded with the shōbijin to the metropolis of “New Kirk City” in his home country, “Rorishika.” There, the monster again wreaks havoc—until the human Japanese protagonists of the film show up and realize that ringing church bells will signal to the monster that it can safely rescue the fairies and return them to Infant Island.

As with the Godzilla series, produced by the same Tōhō team, the Mothra films explicitly addressed Cold War tensions. The original Godzilla film responded directly to the nuclear arms race. In the 1954 film, Godzilla is reawakened by an American hydrogen bomb test in the South Pacific—the same sort of test that had triggered the Lucky Dragon incident that dominated Japanese newspaper headlines for much of that year. The Lucky Dragon 5 was a Japanese fishing vessel that inadvertently drifted into fallout from an American nuclear test on Bikini Atoll. Crew members suffered from radiation poisoning, with one eventually dying. The crisis further deepened when the press reported that tuna contaminated by radioactivity from the test blast had been sold to Japanese consumers. Godzilla spoke to these still-fresh Cold War anxieties with its tale of a prehistoric monster awakened by a nuclear test to wreak havoc on the people of Japan.25

Mothra also alludes to the nuclear arms race: Infant Island, believed to be uninhabited, is a site for nuclear weapons tests. At the start of the film, the crew of a Japanese vessel shipwrecked by a typhoon wash up on its shore—but mysteriously they escape radiation poisoning. After their rescue, they attribute their miraculous lack of symptoms to the properties of a mysterious red juice the previously unknown natives of Infant Island provided to them. This prompts Japan and its ally Rorishika to organize a scientific expedition to investigate the island, which is dispatched under the command of the unscrupulous Nelson—thus launching the plot into motion.

But even more than nuclear testing, Mothra responded directly to another Cold War crisis: the massive 1960 Tokyo demonstrations against Anpo (Igarashi, 2006: 83-102). This subtext is even clearer in the original novella on which the film story was based. There, Japan’s fictional military ally is named Roshirika (an amalgamation of “Russia” + “America” in Japanese pronunciation), and we learn that it has just signed a controversial security treaty with Japan despite considerable popular protests (Nakamura, et al., 1994: 47). Where in the film Mothra wraps its cocoon around Tokyo Tower, in the novella the monster attaches itself to the Diet Building, the actual site of the 1960 protests. As Nakamura Shin’ichi, one of the three authors of the novella would later explain, “The three of us then had the Japanese government invoke the treaty to request the American military to mobilize, which in turn brought the anti-Anpo mass protestors out to surround the Diet Building. We would borrow actual news footage for this part in the film.”26 In the original conception, in other words, the film’s climax, involved an obvious reenactment of the 1960 Anpo protests in front of the Diet Building.

The studio scrubbed these highly politicized references to the US and the 1960 Anpo struggle from the final film script. It also switched the location of the military confrontation from the Diet Building to the Tokyo Tower and ordered the name of the allied country altered from Roshirika to Rorishika, but no one was fooled (Ono, 2007: 102-6, 204). An early review of the film in the Asahi newspaper ignored this geographical subterfuge and (correctly) identified the second country as the U.S.27

Accordingly, Japan’s useless ally in the novella, Roshirika, was an amalgam of the First and Second Worlds, America and Russia. Even in the relatively depoliticized film version, moreover, it remains clear that the Japanese heroes of the film align themselves not with Rorishika, but rather with Infant Island, an imaginary nonaligned member of the Third World. The film leaves the specific geographical location of Infant Island vague. One of the Japanese heroes of the film, the linguistics scholar Chūjō (Koizumi Hiroshi), associates the local written language and mythology with Polynesia—which would make sense, given the premise that the island was a site for nuclear weapons testing, like Bikini Atoll and French Polynesia. But other clues—for example, weather maps and geographical coordinates given for the storm that causes the shipwreck at the opening of the film—suggest a location closer to the Philippines or even Indonesia, host of the Bandung Conference (Ono, 2007: 79).

Clearly, Bandung was on the mind of the film’s creators. As we have already seen, the year Mothra was released saw Tokyo host an Emergency Meeting of AAWA, the main cultural arm of the Bandung movement, to demonstrate solidarity with Japan’s anti-security-treaty protest movement. Mothra spoke to powerful desires for a Japan aligned not with the United States or the Soviet Union (or, for that matter, Rorishika) but rather with the decolonizing nations of the Bandung movement—such as Indonesia, or the fictional Infant Island.28 This ideological undercurrent in Mothra was hardly accidental. Producer Tanaka Tomoyuki commissioned three respected literary authors to compose the initial novella version of the film, which was first published in the mass-circulation weekly Bessatsu Shūkan Asahi in January, 1961.29 In a December 1960 newspaper interview preceding that publication, the three authors announced that the theme of their forthcoming collaboration would shift the focus away from the dangers of nuclear weapons, such as had characterized Gojira and other kaijū films; they would focus instead on contemporary problems faced by oppressed minority cultures around the world.30

The three wrote in chain sequence, each taking charge of one section of the work. The opening section was written by Nakamura Shin’ichirō, a novelist who had previously worked with producer Tanaka on the 1955 film version of Mishima Yukio’s The Sound of Waves (Shione). The middle section was by Fukunaga Takehiko, a poet and novelist also known for his film criticism. The third author, who took charge of the final (and longest) section, was novelist Hotta Yoshie, winner of the Akutagawa Prize in 1950. Hotta was in fact a key figure in Japan’s involvement in the cultural wing of the Bandung Movement, in particular the AAWA, and played a central role in arranging the 1961 Tokyo Emergency Meeting.31 A member of the planning committee that organized the first Asian Writers’ Conference in India in 1956, Hotta was closely involved in the preparations for the first AAWA meeting in 1958 in Tashkent (though he did not attend that conference).32 He would go on to spend decades as a member of the AAWA Central Secretariat. Hotta wrote extensively about the movement in such nonfiction works as Indo de kanagaeta koto (What I thought about in India, 1957) and Shōkoku no unmei, daikoku no unmei (The fate of small nations, the fate of major nations; 1969). Hotta’s fiction too sometimes dealt explicitly with the issues at the heart of the Bandung movement, including his 1965 novel, Sphinx, in which a young female Japanese employee of UNESCO becomes embroiled in underground efforts to support the Algerian War for Independence against France. Her foil in the novel, a shady veteran of Japan’s WWII intelligence service and a trafficker in military surplus who now lives in Cairo, would wryly see the heroine an instance of the “Afro-Asian fever” that seemed to take hold of Japanese youth in the early 1960s, musing that it seems like a strangely distorted version of the wartime Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere discourse (Hotta, 1965: 218).

Hotta’s importance to Third World cultural activism would in 1977 lead to his becoming one of the three Japanese writers to win the Lotus Prize for Literature, the so-called ‘Third World Nobel Prize.’ Given his involvement, it seems almost inevitable that the Mothra series would become a vehicle for Japan’s version of the Bandung Spirit. The 1961 film used a script by Sekizawa Shin’ichi that in broad outlines followed the storyline that Hotta had developed with Nakamura and Fukunaga, but deviated in a number of important details. As we’ve seen, the location of Infant Island is deliberately kept ambiguous in the film, with some of the evidence pointing toward the Indonesian archipelago. This might be in part because Sekizawa, like many other people who worked on the film, had personal Indonesian connections. Over the course of his career Sekizawa produced a number of film scripts with Southeast Asian and Pacific settings—perhaps reflecting his own wartime military service in the region (Ono, 2007: 73-4.). Likewise, producer Tanaka had previously been involved in planning a large-scale Japanese-Indonesian co-production that would have taken up the story of Japanese soldiers stationed in Java who upon surrender deserted their barracks to join the Indonesian nationalist army and fight for independence under Sukarno. That production was canceled at the last minute in 1954 when the Indonesian Foreign Ministry, angered by the failure of negotiations to conclude a war reparations treaty with Japan, refused to issue visas to the film’s crew.33 It was during his 1954 plane ride home from Indonesia that Tanaka—desperate for a new film idea to replace the now-cancelled Indonesian co-production—came up with the original idea for Godzilla.34

Koseki Yūji, the man responsible for the Mothra soundtrack, brought his own history of Indonesian connections. One of Japan’s most successful songwriters since the late 1930s, Koseki produced a soundtrack for the 1961 film that hearkened back to his origins as an enfant terrible of Japan’s classical music scene in the early 1930s, one particularly taken with the exoticism and primitivism of such modern composers as Stravinsky, Moussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Ravel (Kobayashi, 2001: 1:230-1). After switching to popular music composition, Koseki continued to partake of musical exoticism, touching on both foreign and domestic sources. Koseki’s biggest hit compositions, for example, include two songs associated with the indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido— “Night of Iyomante” (Iyomante no yoru, 1949, performed by Itō Hisao) and “Black Lily Song” (“Kuroyuri no uta,” 1953, performed by Orii Shigeko).

For the 1961 film, Koseki composed not only the background soundtrack music, but also the musical numbers that The Peanuts performed on screen, including “Mothra’s Song.” The novella version (in which there are four rather than two shōbijin) describes the stage performance of their signature number as wordlessly communicating something to the linguist Chūjō:

Sitting in the completely sold-out auditorium, Chūjō alone was able to sense a sort of meaning in the humming-like chorus that the women sang. This may have been because of his previous experience on the island, when he had connected with one of the four by what we might call telepathy (spiritual sympathy). Certainly, their singing voices gave off a bright, clear, happy-sounding reverberation. And yet it also harbored a strain of yearning toward something, like a summons to a supernatural entity, the suggestion of a horrifying future certainty.35

A few pages later in the novella, as the stage performance ends, the four remained on stage, we’re told, singing a song that consisted of a single word repeated over and over: “Mothra.” We’re further told that many people in the audience came away with a sense of sadness and cruelty from the performance: the strange music has opened an empathetic bond between the shōbijin and the ordinary Japanese folk in the audience, contrary to the evil promoter Nelson’s design (Nakamura, et al. 1994: 46, 49).

Koseki faced the task of coming up with a new composition for the film that would embody these descriptions. By all accounts, he succeeded brilliantly. The melody he created for “Mothra’s Song” is an instantly memorable earworm. The tune provides an instance of Koseki’s characteristic exoticism, in particular with the pounding percussion, an echo of Polynesian island drumming, that colors the orchestration and dominates the fade out of the studio recording of the song, in which the singers and other instruments fade away, leaving only the drumming patterns for the last twenty seconds of the recording. The song also provides the biggest clue linking fictional Infant Island to Indonesia in the film.

The opening words of the lyrics—“Mosura ya”—are a kind of feint, because they could be Japanese, but quickly the Japanese audience for the film would realize that the words sung by The Peanuts were in another, strange language. Probably at least some would have recognized that the lyrics of the song that shōbijin use to summon are in Bahasa Indonesian. The original Japanese lyrics were most likely drafted by scriptwriter Sekizawa; the film’s producers then hired an Indonesian student at University of Tokyo (probably one of the exchange students sponsored by the Japanese government under the terms of the war reparations treaty that it finally signed with Sukarno in 1958) to translate them into Indonesian. The uncredited student’s translation was then used by The Peanuts in the film and recording.36

Things get even more complicated linguistically a few minutes later in the film. The Peanuts as the shōbijin return to the stage in Tokyo and perform another Koseki composition, “Girl from Infant Island” (“Infanto no musume”). The orchestration again foregrounds exotic drumming. Whereas up to this point the fairies have appeared in scanty ‘native’ costumes (a source of tension between The Peanuts and the studio, with the duo demanding a more conservative design), for this second stage appearance the shōbijin appear costumed in traditional Japanese kimono, and the lyrics they sing are in Japanese.37 Apparently, Indonesian speakers pick up Japanese pretty quickly.

This seemingly mystical ability to communicate across linguistic (and species) boundaries via music or pure sound becomes a kind of motif throughout the film—and in the earlier novella version. We first encounter it through the eyes and ears of Chūjō the linguist who, after discovering strange writing in a mysterious cave on Infant Island, is attacked by a carnivorous plant. The sonic qualities of the alarm beacon he sets off to call for help attract the fairies, who in turn generate a metallic sound (produced on the soundtrack by a Hammond organ, one of Koseki’s favorite instruments).38 Chūjō’s colleagues rush to his rescue, and when he returns to the same location the next day, he confirms a hunch by setting off the alarm again, and as he expects, it once more summons the fairies, who again generate the weird metallic sound. The expedition members recognize that the strange sound is actually a kind of nonverbal language, a form of telepathy by which the fairies can communicate with them. Their message is loud and simple: leave our island in peace. The evil promoter Nelson, however, kidnaps the fairies and absconds to Tokyo with them, setting up the rescue mission by Mothra that occupies the latter half of the film.

Through these musical cues, Koseki and the film’s producers have performed some remarkable sleights of hand. Japanese characters and Infant Island fairies can communicate—telepathically, it seems. (In the published novella version, the communication barrier is further bridged when the linguist Chūjō manages to decode the Infant Island language, which at first sounds to him more like a melody than a language) (Ono, 2007: 61-2). A kind of translinguistic bond exists between them, so that The Peanuts can first sing the Indonesian lyrics to “Mothra Song” and then, without explanation, switch to singing Japanese in their next musical number—as if Indonesians and Japanese understood each other from the start.39 This jibes well with the plot of the film, in which it is the Japanese characters who enjoy a sympathetic rapport with the natives of Infant Island, just as it is the Japanese characters who, after the dismal failure of the Rorishikan military attempts to destroy Mothra, figure out how to communicate with the monster via the sound frequency of ringing church bells—another instance of magical communication via pure musical sound across linguistic and species barriers.

When we trace back through composer Koseki’s earlier career, we find further instances of this motif of magical communication across linguistic boundaries via musical tones. Mothra was not, it turns out, Koseki’s first experience in crossing the Indonesia/Japan divide musically. The composer himself traveled through Southeast Asia on propaganda missions in 1942 and 1943.40 One result of this was that his wartime propaganda song “Flower of Patriotism” (Aikoku no Hana), a 1938 hit for singer Watanabe Hamako, was translated into Indonesian, eventually becoming a standard school song in the postcolonial republic, as Koseki notes with pride in his 1980 autobiography. Reflecting on this unexpected postwar trajectory of his composition, Koseki writes, “I felt vividly the mysterious power of song, able to transcend national boundaries and racial differences to unite human hearts in harmony, and once more realized the significance of my work” (Koseki, 2019: 76-8; See also Kurasawa, 1987: 59-116).

Koseki also composed the theme song for the 1943 propaganda film, Dawn of Freedom (Ano hata o ute, dir. Abe Yutaka and Gerardo de León), a joint Japanese-Philippines collaboration celebrating the Japanese ‘liberation’ of the Philippines from American colonial rule. This live-action film—shot both in the Philippines and in Tokyo film studios—features special effects by Tsuburaya Eiji (who would serve in the same capacity for the Mothra series) and stars Ōkōchi Denjirō. It features another scene of magical communication across linguistic barriers. For much of the film, the Japanese characters surprisingly speak English, the enemy’s tongue, in order to communicate with locals in occupied Manila. But at a climactic moment (backed by dramatic strings on the soundtrack, a theme probably composed by Hayasaka Fumio, who would go on to score many of Kurosawa Akira’s early postwar films) we see another instance of mystical translingual communication. It comes time for the film’s hero, a Filipino soldier who at first fought against the Japanese invasion but now has seen the light and crossed over to the liberator’s side, to say farewell to his closest Japanese soldier compatriot. In a scene that one critic describes as being “shot like a love scene in a Hollywood romance,” each man speaks his own language—English and Japanese—and yet somehow they each magically understand what the other means to say: that Japan and the Philippines are not enemies, but rather allies.41 Linguistic barriers melt away to suggest a shared language of the heart.

Koseki also composed the soundtrack for the landmark 1944 film, Momotarō: Sacred Sailors (Momotarō: Umi no Shinpei, dir. Seo Mitsuyo), a feature-length animation celebrating Japan’s liberation of Southeast Asia from Western colonial rule. Music is central to the film, which was inspired in part by Disney’s 1940 Fantasia—director Seo adopted Disney’s pre-scoring technique, in which the musical soundtrack was created first and the animation drawings second (Hori, 2017: 190-201). Momotarō: Sacred Sailors includes the “A-I-U-E-O Song” (A-I-U-E-O no uta), a Koseki composition akin to the English “ABC.” The song appears in a sequence set on a Japan-occupied Pacific Island that looks a great deal like Java. The local Japanese commanders are trying to teach the local children (instructors and pupils are all Disneyesque animals from a variety of species) the Japanese language, but playful chaos breaks out in the open-air class: the animal pupils bray and howl, each in its own bestial tongue. They would clearly rather frolic than pay attention to the flustered teacher. Suddenly, a nearby Japanese solider-bear pulls out a harmonica and his monkey colleague starts singing the song’s lyrics, the syllabary of the Japanese language. Enthralled by the music, the pupils begin moving their bodies in unison with its rhythms; soon they all join in singing the lyrics in unison. Again, apparently Indonesians pick up Japanese pretty quick. By the time the song sequence ends, the animals are pulling together to cooperate and carry out the labor—cooking, laundry, hauling cargo—that helps the Japanese paratroopers prepared for their next mission: driving the English-speaking imperialist army from a neighboring island. The power of music here magically transcends not just national language boundaries, but species boundaries, pulling the various animals together in struggle against the white human imperialists.

The climax of the film Mothra presents yet another instance. The Japanese protagonists arrive in New Kirk City, clearly modeled after New York City, as Mothra destroys the town in its desperate search for the shōbijin. The protagonists rescue the tiny fairies from the villain Nelson and now need to somehow communicate with the monster to let it know that it can safely retrieve them and return to Infant Island. They hit upon a plan based on sonic frequencies: they realize that the nonlinguistic sound of church bells ringing will replicate the sonic qualities of the alarm bell that first summoned the shōbijin back on Infant Island. They arrange to have all the church bells in New Kirk City rung at once, and the plan works: Mothra uses the sounds to guide him to the location where it can pick up the shōbijin and return them (accompanied by swelling soundtrack music composed by Koseki) to Infant Island. A sonic alliance between the Japanese characters and the potentially violent Third World forces represented by Mothra and the shōbijin has saved the world—including both the First World and the Second World—from catastrophe.42

In sum, in Mothra and elsewhere in their career, The Peanuts’ brand of musical cosmopolitanism participated in the tangle of historical contradictions and desires that characterized the culture of Cold War Japan. Their covers of Anglo-American and Western European hits celebrated Japan’s position as a kind of junior partner in the U.S.-dominated First World and at the same time subtly challenged it by asserting a degree of artistic independence. Simultaneously, the duo also participated in the lively trafficking of songs and styles between Japan and the socialist bloc, unexpectedly becoming along the way the purveyors of a new standard number in the popular music repertoire of the Soviet Union. And in their Afro-Caribbean and Indonesian-inspired repertoire, they spoke to the desires for a Third World Japan. In musical numbers like “Mothra’s Song,” Japan’s imperial connections to Southeast Asia are simultaneously effaced and remembered. In the figure of someone like novelist and AAWA activist Hotta Yoshie, such cosmopolitanism could serve as a means of offering redress for past and present historical violence and for finding ways in which Japanese could participate as allies in the ongoing Cold War projects of decolonization and nonalignment. In other settings, this sort of musical cosmopolitanism could serve as a summons to just dance the night away, embracing the fantasies and desires solicited by exotic rhythms, untroubled by questions of power and historical responsibility. A full accounting of Japan’s Cold War culture and its cosmopolitanisms will need to map out these complex and often self-contradictory connections to the networks of all Three Worlds of the Cold War order.

Bibliography

“Daikaijū Mosura: Shōminzoku no ikaru shōchō.” Yomiuri Shinbun evening edition (24 November 1960), 5.

“Dezaināa ni tenkō ka? Za Pīnattsu.” Shūkan Heibon 10:38 (19 September 1968).

“Gaikoku sutēji date heiki, heiki!” Myōjō 14:9 (August 1965), 114-115.

“Hanagata yushursuhin Za Pīnattsu.” Shūkan Heibon 9:29 (20 July 1967), no page numbers.

“Ichibanki buji ni ōfuku.” Yomiuri shinbun (21 April 1967), 14.

“Ijin-san ni sarawareru ka Piinattsu.” Mainichi Graph (20 June 1965), 14-17.

“Mambo-san.” Time 66:4 (25 July 1955): 66.

“Masumasu kaichō no Za Pīnattsu.” Music Life 10:12 (December 1960), 24-25.

“Moscow e ichibanki tobu.” Yomiuri shinbun evening edition (20 April 1967), 1.

“Nipponjin no chiebukuro 13: Gojira no umi no oya, Tanaka Tomoyuki Tōhō Eiga torishimariyaku sōdanyaku.” Mainichi Shinbun (15 August 1995), 9.

“Sekai no ‘Nankin mame’ ni naru Za Pīnattsu.” Shūkan Heibon 8:14 (7 April 1966), 45;

“Sekai ryokō taidan: Sakamoto Kyū Za Pīnattsu.” Heibon 19:9 (September 1963), 104-106.

“Taihen ninki: Uīn Za Pīnattsu.” Shūkan Heibon 6:47 (26 December 1963), no page numbers.

“Tensei jingo.” Asahi Shinbun (3 December 1962, morning edition), 1.

“Tōkyō shūgeki ni kanari no hakuryoku: ‘Fūshi kigeki’ toshite ichiō matamaro Mosura.” Asahi Shinbun (4 August 1961), evening edition, 5.

“Za Pīnattsu no eigo jitsuryoku.” Shūkan Heibon 8:23 (9 June 1966), 40-42.

Abe, Yasushi. “Ogoreru kashu hisashikarazu.” Shūkan Taishū (6-13 January 1966, double issue), 116-120.

Ampiah, Kweku. “Japan at the Bandung Conference: The Cat Goes to the Mice’s Convention.” Japan Forum 7:1 (1995): 15-24.

Atkins, E. Taylor. Primitive Selves: Koreana in the Japanese Colonial Gaze, 1910-1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Baskett, Michael. The Attractive Empire: Transnational Film Culture in Imperial Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008.

Bhabha, Homi. “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse.” October 28 (1984), 125-133

Bourdaghs, Michael K. Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Bourdaghs, Michael K., Paola Iovene, and Kaley Mason. “Introduction.” In Sound Alignments: Popular Music in Asia’s Cold Wars, edited by Michael K. Bourdaghs, Paola Iovene, and Kaley Mason, 1-39. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

Bourdaghs, Michael. “Japan’s Orient in Song and Dance.” In Sino-Japanese Transculturation: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the End of the Pacific War, edited by Richard King, et al, 167-187. Landham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012.

Cheah, Pheng. What is a World? On Postcolonial Literature as World Literature. Durham: Duke UP, 2016.

Decampo, Nick. Eiga: Cinema in the Philippines During World War II. Mandaluyang City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, 2016.

Dennehy, Kristine. “Overcoming Colonialism at Bandung, 1955.” In Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History: Colonialism, Regionalism, and Borders, ed. Sven Saaler and J. Victor Koschmann, 213-225. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Denning, Michael. Culture in the Age of Three Worlds. London: Verso, 2004.

Denning, Michael. Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Musical Revolution. London: Verso, 2015.

Fellezs, Kevin. Listen But Don’t Ask Question: Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar Across the TransPacific. Durham: Duke University Press, 2019.

Furmanovsky, Michal. “A Complex Fit: The Remaking of Japanese Femininity and Fashion, 1945-65,” Kokusai bunka kenkyū 16 (2012): 43-65.

Gobuichi, Isamu. Shabondama Horidē: Sutādasuto o mō ichido. Tokyo: Nihon Terebi Hōsō, 1995.

Harootunian, H. D. “America’s Japan, Japan’s Japan.” In Japan in the World, ed. Masao Miyoshi and Harootunian, 196-221. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1993.

High, Peter B. The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

Hill, Christopher L. “Tokyo in Tashkent: The Afro-Asian Writers Association and Japanese Cold War Dissent.” Forthcoming in Past & Present 262 (2024).

Hill, Christopher. “Crossed Geographies: Endō and Fanon in Lyon.” Representations 128 (Fall 2014): 93-123.

Hori, Hikari. Promiscuous Media: Film and Visual Culture in Imperial Japan, 1926-1945. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Hosokawa, Shuhei. “Martin Denny and the Development of Musical Exotica.” In Widening the Horizon: Exoticism in Post-War Popular Music, ed. Philip Hayward, 72-93. London: John Libbey, 1999.

Hotta, Yoshie. Sphinx. Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha, 1965.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. “Mothra’s Gigantic Egg: Consuming the South Pacific in 1960s Japan.” In In Godzilla’s Footsteps: Japanese Pop Culture Icons on the Global Stage, edited by William M. Tsutsui and Michiko Ito, 83-102. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945-1970. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Japanese Liaison Committee of Afro-Asian Writers, ed. The Emergency Meeting of the Permanent Bureau of Afro-Asian Writers: Tokyo, March 28-30 1961. Tokyo: Japanese Liaison Committee of Afro-Asian Writers, 1961.

Jones, Andrew. Circuit Listening: Chinese Popular Music in the Global 1960s. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Kim, Seong Un. “Crazy Shows: Entertainment Television in Cold War Japan, 1953-1973.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, 2017.

Kitanaka, Masakazu. Nihon no uta rev. ed. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2003.

Kō, Mamoru. Kayōkyoku: jidai o irodotta utatachi. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2011.

Kobayashi, Atsushi. Nihon eiga ongaku no kyoseitachi, 3 volumes. Tokyo: Tokyo: Waizu Shuppan, 2001-2002.

Koseki, Yūji. Kane yo narihibikie: Koseki Yūji jiden [1980]. Tokyo: Shūeisha, 2019.

Kurasawa, Aiko. “Propaganda Media on Java under the Japanese 1942-1945.” Indonesia 44 (1987): 59-116.

Kurosawa, Susumu, ed. Roots of Japanese Pops, 1955–1970. Tokyo: Shinkō Music, 1995.

Lee, Jun Hee. “‘Rather a Hundred Singing Laborers than a Single Professional’: Imagining the Japanese Masses in the Utagoe Movement, 1948-Present.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, 2020.

Malm, William. “A Century of Proletarian Music in Japan” Journal of Musicological Research 6 (1986):185-206.

Miyagi, Taizo. Japan’s Quest for Stability in Southeast Asia: Navigating the Turning Points in Postwar Asia, trans. Hanabusa Midori. London: Routledge, 2017.

Miyata Teru. “12-sai ni sareta Pīnattsu.” Shūkan Heibon (3 November 1966), 60-63.

Mizutamari, Mayumi. “Hotta Yoshie to Ajia-Afurika Sakka Kaigi (1): Dai-Sansekai to no deai.” Hokkaidō Daigaku bungaku kenkyū kiyō 144 (2014): 73-104.

Mizutamari, Mayumi. “Hotta Yoshie to Ajia-Afurika Sakka Kaigi (2): Seiji to bungaku.” Hokkaidō Daigaku bungaku kenkyū kiyō 147 (2015): 67-103.

Nakamura, Shin’ichi, Fukunaga Takehiko, and Hotta Yoshie. Hakkō yōsei to Mosura. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1994.

Nakamura, Shin’ichi. “Atogaki: Kaisō Mosura.” in Hakkō yōsei to Mosura, edited by Nakamura Shin’ichi, Fukunaga Takehiko, and Hotta Yoshie, 169-172. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1994.

Nick Kapur. Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Noji, Tsuneyoshi. Watanabe Shin monogatari: Shōwa no sutaa o kizuita otoko. Tokyo: Magajin Hausu, 2010.

Nornes, Abé Mark. Japanese Documentary Film: The Meiji Era through Hiroshima. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Ono, Shuntarō. Mosura no seishinshi. Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2007.

Onzō, Shigeru. Nippon POP no ōgon jidai. Tokyo: KK Besuto Serāzu, 2001.

Osakabe, Yoshinori. Koseki Yūji: Ryūkōka sakkyokuka to gekidō no Shōwa. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 2019.

Pope, Edgar W. “Songs of Empire: Continental Asia in Japanese Wartime Popular Music.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Washington, 1993.

Shima, Yukio. “Oshaberi jokkī.” Music Life 11:10 (October 1961), 84-87.

Steinberg, Marc. Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Take, Hideki. Yomu J-Pop: 1945-1999 shiteki zenshi. Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 1999.

Tamaki, Kenji. “Karon: Gojira no natsu.” Mainichi Shinbun newspaper (26 July 2011), 3.

Taussig, Michael. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. New York: Routledge, 1993.

The Peanuts. 12 Inolvidables con The Peanuts, Son-Art D-474 (1974). Source: https://www.discogss.com/The-Peanuts-12-Inolvidables-con-The-Peanuts/release/13874722 (accessed 18 July 2020).

Wajima, Yūsuke. Odoru Shōwa kayō: rizumuu kara miru taishū ongaku. Tokyo: NHK Shuppan, 2015.

Wilson, Rob. “‘World Gone Wrong’: Thomas Friedman’s World Gone Flat and Pascale Casanova’s World Republic against the Multitudes of ‘Oceania’.” Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 33:2 (2007): 177-194.

Yamanouchi, Shigemi. Kuroi hitomi kara hyakumanbon no bara made: Roshia ai shōkashū. Tokyo: Tōyō Shoten, 2002.

Yoshii, Hiroaki. Gojira Mosura Gensuibaku: Tokusatsu eiga no shakaigaku. Tokyo: Serika Shobō, 2007.

Notes

- Earlier versions of some of the material here first appeared in Bourdaghs, et al., “Introduction,” 1-39.

- See for example Hill, 2014: 93-123.

- Ampiah, 1995: 15-24. See also Dennehy, 2007: 213-225.

- Denning, 2004. On “worlding,” see, for example, Cheah 2016, and Wilson, 2007: 177-194.

- For surveys of this boom in foreign cover songs, see Kitanaka, 2003: 106-114; and Onzō, 2001: 38-66.

- The most extensive source in English on utagoe is Lee, 2020. See also Malm, 1986.

- Gobuichi Isamu, Shabondama Horidē: Sutādasuto o mō ichido (Tokyo: Nihon Terebi Hōsō, 1995). The Peanuts also regularly appeared on The Hit Parade, which aired 1959-1970 on the Fuji TV network.

- “Ijin-san ni sarawareru ka Piinattsu,” Mainichi Graph (20 June 1965), 14-17. This passage appears on 15.

- The glossy 1962 musical Yume de aimashō (Meet me in my dreams, dir. Saeki Kōzō), a widescreen production from the Tōhō Studio, presented a fictionalized version of this training regime, with The Peanuts playing themselves in a supporting role.

- For a critical discussion of the rise of modernization theory in Japan Studies as a form of Cold War ideology, see Harootunian, 1993.

- “Za Pīnattsu no eigo jitsuryoku,” Shūkan Heibon 8:23 (9 June 1966), 40-42. See also the preview of their upcoming Ed Sullivan Show appearance in “Sekai no ‘Nankin mame’ ni naru Za Pīnattsu,” Shūkan Heibon 8:14 (7 April 1966), 45; and the interview with the duo about their experiences on The Danny Kaye Show in Miyata, 1966.

- See the roundtable dialogue between Sakamoto and The Peanuts as the latter were planning their first overseas appearances: “Sekai ryokō taidan: Sakamoto Kyū Za Pīnattsu,” Heibon 19:9 (September 1963), 104-106.

- “Masumasu kaichō no Za Pīnattsu,” Music Life 10:12 (December 1960), 24-25. The article stresses the role that Miyagawa plays in coming up with novel and unexpected arrangements for the duo’s recordings.

- See, for example, an interview feature in which The Peanuts, just returned from performing and recording in West Germany and France, offer advice to singer Hirota Mieko, about to make her first overseas debut at the Newport Jazz Festival in America: “Gaikoku sutēji date heiki, heiki!” Myōjō 14:9 (August 1965), 114-115.

- One weekly tabloid featured three-page photo spreads covering the duo’s travels to Vienna and later Amsterdam to appear on episodes of The Caterina Valente show, broadcast throughout Western Europe: “Taihen ninki: Uīn Za Pīnattsu,” Shūkan Heibon 6:47 (26 December 1963), no page numbers; and “Hanagata yushursuhin Za Pīnattsu,” Shūkan Heibon 9:29 (20 July 1967), no page numbers.

- “Ijin-san ni sarawareru ka Piinattsu,” 15. Watanabe Misa’s global strategy for the duo is also reported in Abe Yasushi, “Ogoreru kashu hisashikarazu,” Shūkan Taishū (6-13 January 1966, double issue), 116-120.

- On the song’s musical and lyrical complexity, see Kō, 2011: 39-43.

- “Dezaināa ni tenkō ka? Za Pīnattsu,” Shūkan Heibon 10:38 (19 September 1968), 49.

- The Peanuts were not the only musical artist of the era to pursue an identification with France. Kamayatsu Hiroshi, a member of the enormously popular 1960s Group Sounds band The Spiders and later a successful solo artist, was the son of a Japanese-American jazz singer Tib Kamayatsu who despaired of ever enjoying a successful career in the U.S. in the face of the racism of the music industry and moved to Japan permanently in 1929. Kamayatsu frequently cited his resentment of the way Japanese Americans were treated in the States and even knowingly titled one of his hit compositions “No-No Boy” (1966) the boy-loses-girl lyrics concealing his allusion to the tradition of “No-No Boys,” the Japanese Americans incarcerated in WWII concentration camps who refused to sign loyalty oaths to the U.S. As part of his distancing of himself from the U.S., Kamayatsu appropriated a French image, taking on the nickname “Monsieur Kamayatsu” and wearing French designer clothes. He scored what became a signature number in 1975 with his original composition, “Have You Ever Smoked a Gauloises?” (Gorowazū o sutta kotoga aru kai?), the B-side to his hit record “To My Dear Friends” (Waga yoki tomo yo). See Bourdaghs, 2012: 137-147.

- “Moscow e ichibanki tobu,” Yomiuri shinbun evening edition(20 April 1967), 1; “Ichibanki buji ni ōfuku,” Yomiuri shinbun (21 April 1967), 14; Noji, Watanabe Shin monogatari 116-7.

- Shima, 1961: 84-87. See the article surveying Sucu Sucu as the latest “New Rhythm” dance music boom to hit Japan: “Kakusha issei ni Suku Suku gassen” in the August 1961 issue of Music Life, reprinted in Kurosawa, 1995: 144. On the Sucu Sucu boom in Japan, see Wajima, 2015: 153-7.

- The Peanuts, 12 Inolvidables con The Peanuts, Son-Art D-474 (1974). Source: https://www.discogss.com/The-Peanuts-12-Inolvidables-con-The-Peanuts/release/13874722 (accessed 18 July 2020).

- “Mambo-san,” Time 66:4(25 July 1955): 66.

- On earlier forms of exoticism in Japanese popular music during the wartime empire, see, for example, Atkins, 2010; Fellezs, 2019; Pope, 1993; and Bourdaghs, 2012: 167-187.

- On Godzilla and its relation to the Lucky Dragon incident, see Igarashi, 2000:104-30; and Yoshii, 2007: 23-60.

- Nakamura 1994, 169-172. This passage appears on 171. See also Ono, 2007: 180-4.

- “Tōkyō shūgeki ni kanari no hakuryoku: ‘Fūshi kigeki’ toshite ichiō matamaro Mosura,” Asahi Shinbun (4 August 1961), evening edition, 5.

- A 1962 editorial column in the Asahi newspaper, for example, noted the overseas popularity of Mothra and other recent Japanese sci-fi films and explained that, “Given that the intention of the filmmakers running throughout these productions is to oppose nuclear warfare, promote international cooperation in science and technology, and to oppose the misuse of scientific inventions, it is no mystery that they would find a warm welcome not just in the countries of Asia and Africa, but also in America and Europe.” “Tensei jingo” column, Asahi Shinbun (3 December 1962, morning edition), 1.

- On the original novella version, see Ono, 2007: 14-25, and Igarashi, 2006. Note that Igarashi misidentifies one of the authors of the novel, ironically replacing Hotta Yoshie with his sometime rival, Takeda Taijun.

- “Daikaijū Mosura: Shōminzoku no ikaru shōchō,” Yomiuri Shinbun evening edition (24 November 1960), 5. See also Ono, Mosura no seishinshi, 17.

- On Hotta’s long connection to AAWA, see two articles by Mizutamari Mayumi: Mizutamari 2014, and Mizutamari 2015.

- On Japanese writers at the Tashkent conference, see Hill, 2024.

- Ono, Mosura no seishinshi, 143-5. See also Tamaki Kenji, “Karon: Gojira no natsu,” Mainichi Shinbun newspaper (26 July 2011), 3.

- “Nipponjin no chiebukuro 13: Gojira no umi no oya, Tanaka Tomoyuki Tōhō Eiga torishimariyaku sōdanyaku,” Mainichi Shinbun newspaper (15 August 1995), 9.

- Nakamura, et al. 1994: 37. This comes from the section of the novella written by Fukunaga.

- On the history of the Indonesian lyrics, see Kobayashi, 2001: 1:222-6; and Ono, 2007: 135-155.

- The Peanuts describe how they cried when they first saw the revealing costume design and fought with the studio and director for less revealing outfits in Shima, “Oshabari jokkī,” 86.

- On Koseki’s history of using the Hammond organ, see Kobayashi, 2001: 1:207, 218-9; and Ono, 2007: 59-60.

- In Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), the second film of the Mothra series, the linguistic scramble intensifies: the leader of the native tribe on Infant Island can now speak Japanese, as do the shōbijin, and while the latter reprise “Mothra’s Song” with its Indonesian lyrics, they also sing two new songs, “Mahala Mothra” and “The Sacred Spring” (Sei naru izumi), composed for the film by Ifukube Akira (composer of the original Godzilla theme music)—and with lyrics in Tagalog! By the third film in the series, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964), the problem has been side-stepped: the fairies now summon Mothra with a song with Japanese lyrics: “Cry for Happiness” (Shiawase o yobu), composed by Miyagawa Hiroshi, lyrics by Iwatani Tokiko.

- Ono, 2007: 75-7. On Koseki’s wartime connection to Southeast Asia, see also Osakabe, 2019: 106-38.

- Nornes, 2003: 109. Nornes also notes the “florid music” that backs this remarkable sequence. In the film’s credits, the soundtrack composer is listed as Kasuga Kunio, but this is a fictitious name: see Kobayashi,2001:204. The film’s use of staged scenes involving real American P.O.W.’s would bring war crimes charges on the Japanese staff after surrender, though those charges were dropped when the actual GI’s used in the film testified that they had been well treated during the production; see Decampo, 2016: 239-241. For more on the film, see Baskett, 2008: 100-102; and High, 2003: 451-456.

- The bells are in a sense the counterpart to the drums the Infant Island natives use to warn away intruders—another nonverbal sonic message.