Abstract: Paper City (2021), directed by Adrian Francis, is a documentary film that highlights the 70th anniversary of the firebombing of Tokyo on March 10, 1945. The film presents three elderly survivors’ oral accounts of the firebombing and observes their work as memory activists in a long campaign to compel the Japanese government to publicly memorialize the event in a way commensurate with its enormous devastation. Reflecting on issues of memory and forgetting, Francis intends the film as a way of passing survivors’ experiences to audiences, who can help to transfer memory to others and to generations beyond.

Keywords: Tokyo firebombing; air raids Japan; war memory Japan; war documentary; memory activists

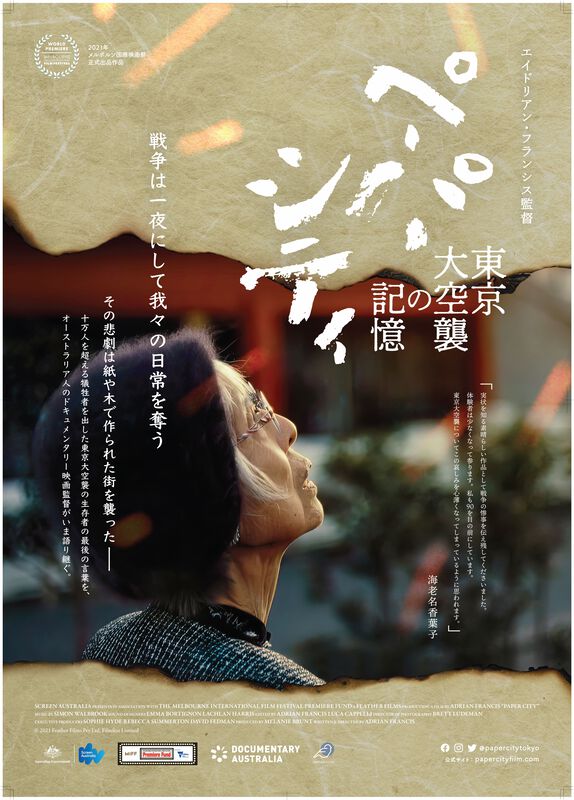

Film poster for Paper City. Image provided by Adrian Francis.

Paper City (2021) is a reflective, powerful, groundbreaking documentary film that highlights the 70th anniversary of the firebombing of Tokyo on March 10, 1945, the deadliest air raid with conventional weapons in history.

The film was made against the background of more than seven decades of willful forgetting by the United States and Japan of the devastating firestorm in which more than 100,000 civilians were killed in one night. In both countries, historical amnesia of the attack since the war has been rooted in a similar desire to avoid culpability.

Forgetting has enabled the U.S. to evade accountability for the firebombing as well as air raids on 66 other cities across Japan in the last five months of the war. Suppressing the memory of those attacks has also helped Japan shun its own responsibility for the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians—before Hiroshima and Nagasaki—when defeat and surrender were clearly inevitable.

Paper City presents oral accounts of three elderly survivors of the firebombing: Minoru Tsukiyama, Michiko Kiyooka and Hiroshi Hoshino, with their personal memories of trauma and loss interspersed throughout the film. It also devotes considerable attention to the ongoing work of the unassuming, dedicated memory activists culminating in the pivotal 70th anniversary of the firebombing in 2015.

In their mid-eighties or early nineties at the time of filming, the central concern of the survivors was that awareness of the catastrophe and its significance may be lost for future generations if the Japanese government continues to resist honoring the victims and inscribing the event in public memory, as it has done since the early postwar years. The efforts of these three individuals, along with others, are epitomized in the film’s epigraph from Milan Kundera, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

People gather outside the Tokyo Memorial Hall before a memorial service on the 78th anniversary of the Tokyo firebombing on March 10, 2023. Photo provided by the author.

The film’s three main subjects were involved with various citizens’ groups as part of a movement that began in the late 1960s to compel the Japanese government to publicly memorialize the firebombing in a way commensurate with its enormous devastation. Paper City refers briefly to some of the initiatives and achievements during these years, as intermittent progress was made mostly in the 1970s and early 1990s, followed by major setbacks. The director wisely does not delve into the complexities and vicissitudes of their struggle, but it may be helpful to mention a few key developments that led to the circumstances of the 70th anniversary.

The high point of progress in their struggle came in the early to mid 1990s, when the Tokyo government approved tentative plans for a peace museum that was to feature discussion of the context of the firebombing, including issues such as Japan’s aggression and its bombing of civilians in Chinese cities in the late 1930s. However, a right-wing revisionist backlash against considerations of war responsibility succeeded in nullifying plans for the museum in 1999.

The modest public monument in Yokoamicho Park for the victims of the Tokyo firebombing on the 78th anniversary on March 10, 2023. Photo provided by the author.

The Tokyo government then co-opted the interests of the activists by building a small memorial in 2001 in Yokoamicho Park, a place dedicated primarily to honoring the victims of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. The activists, however, ironically felt compelled to oppose the memorial’s construction, finding it insufficient because it was not built with an accompanying museum and it echoed the “Japan as victim” narrative rather than providing context about the war. The effects of these critical reversals were mitigated somewhat by the construction in 2002 of a small, privately funded research center and museum, the Center of the Tokyo Air Raids and War Damage, which often hosts meetings and events related to the firebombing.

Another significant disappointment was the outcome of the first large-scale lawsuit against the government by more than one hundred firebombing survivors including Kiyooka and Hoshino, in which the plaintiffs demanded an apology and compensation from the government based on its responsibility for the firebombing. In 2009, the Tokyo District Court ruled against the plaintiffs.

Instead of trying to explain the history of the citizens’ campaign, Paper City creates interest and tension by emphasizing the present as the three protagonists organize and speak publicly in their fight to effect legislative change around the inflection point of the 70th anniversary, which they sense may be the last opportunity for their voices to be heard. Deeply disappointed but not defeated or cynical, they hope for meaningful change but seem to know that the chances of the government changing its position on memorializing the firebombing dead are low. The government’s apparent strategy of intransigence and delay seems to rely primarily on simply waiting for the survivors to pass away. The film links this stonewalling with the government’s controversial passing of historic security bills in 2015 that weakened Article 9 of the Constitution, outlawing the use of force as an instrument of foreign policy, suggesting that escalating Japan’s militarization precluded reflections on war responsibility.

In a scene at a public meeting late in the film, a woman named Kazuko Kusano bluntly and memorably describes the inadequacy and disregard evident in the public remembering of those killed in the attack: “In Tokyo we don’t have a grave or a museum, and the ashes of the dead are stored in urns against a wall, at the rear of the earthquake memorial. We want this to be recognized.”

With the passing of Tsukiyama, Kiyooka and Hoshino since the completion of filming in 2016, Paper City preserves and passes down the experiences and aspirations of a few survivors, making a significant contribution to public memory. Director Adrian Francis explains on the documentary’s website how he came to understand the need for their voices to be shared:

So why don’t we remember the Tokyo fire bombings? What happened to the survivors? Are they reluctant to talk? Would they rather forget? As I began to meet survivors, I saw that nothing could be further from the truth. For them, remembering is not passive—it is an action, a verb. They are deeply compelled to speak about what happened; their problem is few want to listen. I decided I wanted to tell the story of the firebombing from their point of view.

Michael F. Lynch

Cinema, The Pacific War, and the Tokyo Firebombing

Michael F. Lynch (ML): Growing up in Australia, then living in Japan, have you seen any films that left a strong impression on you about the Asia Pacific War?

Adrian Francis (AF): I haven’t really watched so many films about the Asia Pacific War. I was lucky to attend a Tokyo screening of Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain held by Donald Richie in Tokyo. He hosted a series of postwar Japanese films that he was somehow connected to (sometimes he was on set or had a relationship with the director). Fires on the Plain is an extremely bleak account of a Japanese soldier in the dying days of Imperial Japanese Army’s campaign in the Philippines. This is a war film that seems utterly without hope or redemption of any kind, brutal in its depiction of depravity.

ML: Can you recall watching any films referring to the 1945 firebombing of Tokyo?

AF: The firebombing of Tokyo is something that I have never really seen depicted directly on film. I remember seeing the aftermath in some Japanese films—the destroyed city, the city rebuilding, people still living in poverty—but I can’t pinpoint exactly where. Although I haven’t seen the whole film, I did see an excerpt from a film called War and Youth at a small private museum, the Center of the Tokyo Air Raids and War Damage. This shows an extended reenactment of the March 10 attack.

ML: What are your impressions of any Japanese films, older or more recent ones, that you have watched dealing with the war? Do you recall any of them referring to or mentioning the firebombing; or being critical of the United States, or the Japanese wartime government or emperor?

AF: In general, I’m not drawn to films about the war. I did however see Koji Wakamatsu’s Caterpillar, which is a fiercely anti-nationalist and anti-war film. And obviously Grave of the Fireflies, which is perhaps one of the most widely known Japanese films about the war both inside and outside Japan. I think most of the films I’ve seen are about the aftermath of war rather than depictions of the fighting itself. Or they allude to the firebombing or the war, which either happens off screen or is represented indirectly, such as in the Godzilla movies.

ML: How and when did you become interested in the Tokyo firebombing?

AF: I was never very aware of the firebombing until I saw The Fog of War, Errol Morris’s portrait of former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. It is really just one sequence in the movie, but it is quite a shocking introduction to how much destruction and death the firebombing brought upon the city. 100,000 people killed; a quarter of the city destroyed. And that this shocking war crime was just the beginning of a five-month bombing campaign across Japan, which targeted 66 cities and the civilians in them—before the two atomic bombs.

Like many Australians of my generation, I grew up with stories of the cruelty suffered by Allied civilians and POWs at the hands of the Japanese military. But apart from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I was taught nothing about how Japanese civilians experienced the war.

After watching The Fog of War, I began to ask Japanese friends about the attack. Many people I spoke to didn’t know much, other than the fact that Tokyo had been bombed. Most weren’t aware of the size or significance of the destruction. Or that since the mid-60s, survivors across Japan have been campaigning for government recognition in various forms (memorials, reparations, museums, an apology) both as a means of justice, and as a way to fight historical amnesia about the Tokyo firebombing and other air raids.

I began to wonder about the survivors. Were they still alive? Did they want to talk? Would they prefer to forget?

ML: Before making Paper City, what kind of research did you undertake to learn more about the attack and its context?

AF: After talking to people around me, I turned to the web. My Japanese reading ability is not particularly high, so most of my initial research was in English. There is significantly more online about the firebombing than there was a decade ago. Japan Air Raids, a bilingual online archive, was a very helpful start. One thing that was foundational in shaping the film’s direction was finding two papers by Cary Karakas, a professor at City University of New York. “Place, Public Memory, and the Tokyo Air Raids” and “Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Compensation for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids” were my introduction to survivors’ years of “memory activism” and to local resources in Tokyo, namely the Bereaved Families Association, a survivor activist group, and a private museum, the Center of the Tokyo Air Raids and War Damage.

From the very beginning, the film I wanted to make seemed as much about remembering (or forgetting) the firebombing as about the bombing itself. I started to read some books that covered the Tokyo bombing (and other historical bombings) through this lens of memory, such as The Destruction of Memory by Robert Bevan and Among the Dead Cities by A.C. Grayling.

A monument for victims of the Tokyo firebombing near Kototoi Bridge, where many people died. Photo provided by the author.

Planning and Making Paper City

ML: When you were planning, shooting, and editing the film, how did you envision your audience?

AF: We thought that the film might tend to appeal to older people, although we definitely wanted university and high school students to be able to watch the film, too. Of course, it has a natural audience in Japan and the U.S., and to those interested in history, war, and justice and human rights issues.

ML: What do you want people to take away from the film?

AF: We would like to reach as broad an audience as we can—both inside Japan and abroad. One of the central themes of Paper City is the ways that we record and pass on memory. This continues with audience members themselves, who in viewing the film become “witnesses” to the stories of survivors—and can become part of the chain of transferring memory to the people around them, and to generations beyond.

I realize that there is a desire in Japan to talk about these things, but it can often be difficult to start the discussion. I would be very happy if this film could help to start a dialogue across generations and within families about the legacy of the air raids and the war—as discussion continues on revising Japan’s “Peace” Constitution—and about what kind of future Japan wants for itself. Perhaps the film could even be one small part of building pressure on the governments of Japan and Tokyo to act in meeting the demands of survivors.

I’d also hope Paper City gives people pause to think about how bombing campaigns are used in warfare still today, and that the trauma of aerial strikes can mark survivors for life. We see it continue again and again—in Vietnam, Korea, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Palestine, and Ukraine.

And perhaps for viewers to reflect on the film’s central themes of memory and forgetting, specifically what we choose to keep and discard about the past, and why. Even after 78 years, there are many on the Allied side in World War Two who simply want to believe that war crimes against Japanese or German civilians committed are justifiable because of terrible German and Japanese atrocities elsewhere.

ML: How and why did you decide to focus on the three survivors, Minoru Tsukiyama, Michiko Kiyooka, and Hiroshi Hoshino, who were in their mid 80s to early 90s at the time, for the main structure of the film?

AF: Following the stories of three survivors allows us to broaden the scope of the film in a way that one person’s story perhaps wouldn’t. It allows us to get a better sense of the scale of the attacks, as our three protagonists represent three of many neighborhoods that were devastated—Asakusa, Oshiage, and Morishita. On top of that, the three survivors show us different types of memory activism, from political campaigns and collecting signatures, to erecting memorials and recording the names of the dead.

ML: Did you consider other approaches to tell the story?

AF: We didn’t really consider other approaches. Some people suggested we should tell the story in a more “balanced” way by interviewing U.S. pilots or officials. But from the beginning I wanted to tell the story in the words and from the point of view of civilians who were on the ground that night.

ML: What were the major challenges you encountered in making Paper City?

AF: One of the biggest issues for me was working within the limits of my modest Japanese language ability, particularly while we were shooting. I’m not so used to speaking to elderly people, and the language of wartime can sometimes be difficult even for younger Japanese to understand. Looking back at our footage, there were times when I didn’t fully grasp what was being said to me at the time and I missed opportunities to follow up with a question.

The other challenge was conveying our intentions to the three survivors featured in the film, who were all in their 80s and 90s when we shot. While they were used to short interviews with news media for the anniversary of the firebombing, it was harder for them to understand our more observational approach, coming back again and again to shoot over a year and a half. I’m sure they got a little frustrated with me at times, but they were always gracious and open.

The editing was immensely challenging. We had assembled around 45 hours of footage. First, we knew we had a responsibility to the three survivors, to convey their testimonies and their emotional journeys. We also had to make clear to the audience the history and complexity of the survivors’ post-war campaign for recognition. And we were making a film about memory in which the action happens in the present day. It took a lot of work to balance these elements in a way that would be cohesive and compelling for an audience.

ML: Was it difficult for you to gain the confidence of the three survivors featured in the film, or to convey your vision of the film to them?

AF: It wasn’t difficult at all to gain the trust of the survivors. Before meeting them, I had wondered if they might have some trepidation about talking to me—a filmmaker from an Allied country—but nothing could have been further from the truth.

The thing that struck me was that these people were so compelled to memorialize the attacks and talk about their losses—their families and friends, their homes, their livelihoods. Their problem is that few people have been willing to listen. So they were very open to sharing their stories with me.

ML: In the Academy Award-winning documentary The Fog of War, Robert McNamara quotes General Curtis LeMay, his superior at the time and the architect of the Tokyo bombing, as saying, “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” McNamara adds, “And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals.” Did any of the people you interviewed or encountered for the film express anger or bitterness about the attack as an atrocity by the United States?

AF: I didn’t encounter much direct anger at the U.S. from the survivors I talked to. Mr. Hoshino did express how angry he was at what U.S. forces had done to Tokyo and its civilian population, but he was equally furious with the way civilians were treated as second-class citizens under years of militaristic rule. My impression is that people’s initial anger towards the U.S. has gradually transferred into anger towards their own government.

Most survivors seem to be under no illusions about how Japanese imperialism led their country into war in the first place, and ultimately put them on the front lines. It is a very sore point for them that after losing their homes, loved ones, and way of life in the firebombing, their own government all but abandoned them after the war. In contrast to former soldiers and their families, who have been treated generously by the state, civilians have received nothing.

I see it as a kind of double erasure. First, at the hands of the U.S. bombers, which literally wiped their homes and loved ones from the map; and then in the post-war willingness of both the U.S. and Japanese governments to forget.

ML: In what way(s) do you find it significant that the film was shot around the time of the 70th anniversary of the firebombing?

AF: The largest part of shooting occurred over a year and a bit from the 70th to 71st anniversaries of the Tokyo firebombing, in 2015 and 2016. This was a very significant moment in the postwar activism of survivors, who viewed this as a last big push to get the Japanese government to act on their demands. They seemed to have some momentum on their side, with a new multiparty parliamentary caucus behind their cause, as well as good support in the media. There was optimism in the air.

One of the three main survivors in Paper City, Hiroshi Hoshino, who was then president of the Bereaved Families Association, told me he thought it might be a turning point in their struggle. He also realized though, that with the advanced age of survivors, he and many others would not be around to continue the fight once the 80th anniversary came around.

Activism vs. Intransigence

ML: Is it accurate to say that the film tries to balance the desire not to appear political itself, with faithfully presenting the activist nature of the decades of work by Mr. Tsukiyama, Ms. Kiyooka, and Mr. Hoshino?

AF: I think so. I never set out to make a political film per se. I started with a question, not an answer. I wanted the film to have a quiet beauty and dignity too, to be a fitting tribute to the memory of civilian victims. However, after beginning to shoot with survivors, it became clear that their activism was central to their stories and lives—had defined them for decades. Leaving this out would have been an egregious (and ideological) omission on our part.

ML: Could you briefly explain the argument of the lawyer for the citizens’ group, Taketoshi Nakayama, about why the government bears responsibility for the Tokyo firebombing and also for hundreds of thousands of other civilian deaths in the latter stages of the war?

AF: By the middle of 1944, the Japanese military and political establishment knew that there was no path to victory in the war. There were some inside the establishment who advocated preparing a pathway to surrender. As we know, the surrender came much later, in August 1945, after five months of devastating bombings against 66 urban centers across the country, before the final atomic blows to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Between the March 10 Tokyo firebombing and August 15, the Japanese leadership went to bed each night knowing that the U.S. would bomb cities and kill civilians that night. And yet the war continued. If a Japanese surrender had come earlier, the bombings of Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and countless other cities would never have occurred, and hundreds of thousands of lives would have been spared.

Not only this, but civilians were under government instruction not to flee bombing raids, but to stay and fight the ensuing fires that ripped through neighborhoods and buildings made of wood and paper. This was their duty as Imperial subjects. From the point of view of many who survived, the Japanese government bears a direct moral responsibility for putting their lives at risk.

The Passing Generation and the Future

ML: Near the end of the film, we learn that Ms. Kiyooka and Mr. Hoshino passed away before the film was completed. Mr. Tsukiyama, who was alive at that time, died in 2021. Do you see any evidence that younger Japanese will join this cause of recognizing and honoring the firebombing victims?

AF: This is really hard to say. There are elderly survivors who continue to campaign on the issue. Sachiko Kawai, who holds a solo rally in front of the Diet building each week, is but one. The Bereaved Families Association and the National Air Raid Victim Liaison Committee continue to work on persuading lawmakers to take action on the issue—especially on granting some kind of relief to those that were worst affected. There are also numerous scholars, historians, writers, lawyers, and lawmakers who are doing invaluable work to bring the horrors of the firebombing to light—particularly in Japan and the U.S. There is certainly more awareness in the English-speaking world about the bombings than when I began research on the film. Perhaps one of the most prominent examples is Malcolm Gladwell’s book Bomber Mafia. I would hope that Paper City can be a small part of continuing this conversation.

Reception

ML: Paper City won the Best Melbourne Documentary at the 2022 Melbourne Documentary Film Festival and the Audience Award at the 2022 Tokyo Documentary Film Festival. It has been screened at several film festivals in countries including Romania, Australia, the United States, and Germany (at “Nippon Connection,” the world’s largest Japanese film festival). Would you share your thoughts about its international reception at screenings and on social media?

AF: The only physical screenings I’ve had a chance to attend outside of Japan were at Nippon Connection in Germany. Audiences there were very receptive to the film. I always sit in the back row, and people were very still, and of course, this is the kind of film that elicits quiet sobs from the audience.

In the German Q&A sessions and from people reaching out to me on social media after screenings in Australia and the U.S., it seems that for many of them Paper City was their introduction to the firebombing. Like me, it seems that they were also not taught about it in school. For U.S. audiences in particular, I’d like to think that watching the film gives them pause to think about the ethics of bombing civilians. Too often it seems like people are happy to repeat that the bombings of Japanese and German cities were a necessary evil.

ML: Some films, for example Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken (2014), that deal with Japan and the Asia Pacific War, have been shrilly denounced by right-wing nationalists in Japan as racist and anti-Japanese. Now that Paper City has been screened for a few weeks in Tokyo and will be shown in several other Japanese cities in the next few months, are you aware of any negative attention or protests against the film?

AF: As far as I’m aware, there hasn’t been any negative publicity around the film. I cannot see why there would be if people have a chance to watch it. The film lays bare the postwar treatment of air raid survivors by the Japanese and metropolitan governments, but I think it would be hard to characterize it as anti-Japanese. Rather I think it’s pro-civilian. You could only argue it’s anti-Japanese if you equate the nation with the government, as opposed to viewing a country as its people.

ML: What are your impressions of the audiences’ responses in Japan thus far, on the 78th anniversary of the incendiary attacks throughout Japan in 1945?

AF: Paper City had its Japan premiere in competition at the Tokyo Documentary Film Festival in December (2022), where we were lucky enough to pick up the Audience Award. Personally, this was very exciting. It’s a Tokyo story, made here, and this is where our biggest and most important audience is. Now that it’s released here, we have received a warm reaction from many media outlets, which is essential for the success of a small independent film like this. Of course, many older people have come to see the film who have some personal connection to the firebombing—either as survivors themselves, or the children, grandchildren, nieces, or nephews of survivors. I’ve been encouraged to see some younger people and non-Japanese people too (which is why we decided to screen the film with English subtitles).

The Q&A sessions and the direct feedback from audiences have been wonderful. It runs the gamut. For bombing survivors, there seems to be some validation in seeing their emotional lives and struggles on the big screen. In contrast, many younger people have told me that Paper City is really their first introduction to many basic facts of the firebombing—including how many people died, the extent of damage, and the historical significance of March 10. A lot of these younger people are embarrassed that they didn’t know even the most basic facts. The film focuses on Tokyo, but it does mention the other 66 cities that were firebombed, and I’m very encouraged that Paper City has been invited to screen in some of these cities too, because each of these cities has its own story of death and destruction, memory and forgetting. (Some cities—such as Osaka and Yokohama—are also releasing the film to coincide with the anniversary of their own air raids.)

ML: Finally, do you have some aspiration about how the film might influence audiences and social attitudes?

AF: I would love if the film could somehow encourage discussion across generations, including within families, about the legacy of the firebombing in particular, and WWII more generally. And if the film could encourage people to reflect critically on their own education—on what they were taught, what was omitted, and perhaps why this was the case. If this could contribute to the pressure on the government to take some kind of action (to compensate or memorialize victims), then that would be the most wonderful outcome of all.

Paper City is currently screening at selected cinemas in Japan. For more information, please visit https://papercityfilm.com/.