Abstract: The Industrial Heritage Information Center in Tokyo (IHIC) was opened in 2020 as part of the Japanese government’s 2015 agreement with UNESCO to disclose the full history behind each newly listed World Heritage site. However, the Center has been disseminating a one-dimensional narrative that denies that forced labor has ever happened and labels claims to the contrary as “groundless lies.” Testimonies of Korean, Chinese, or Allied POW forced laborers are entirely absent. This article examines the content of the IHIC’s guided tours and their most repeated claims. It also covers the debate surrounding the legitimacy and reliability of oral histories.

Keywords: Japan’s history wars, UNESCO, Tokyo Industrial Heritage Information Center (IHIC), forced labor, Hashima/Gunkanjima

In 2015, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee added “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining” to the World Heritage List. Due to the history of forced labor and wartime mobilization surrounding these sites, the Japanese government agreed to open an information center to disclose the full history behind each site after protests from the government of the Republic of Korea and several civic groups. Consequently, the Industrial Heritage Information Center (IHIC) was opened in 2020, in Tokyo. This paper will introduce the IHIC and, in particular, its two-hour guided tour in Japanese in order to answer the following questions: What does a guided tour in Japanese at the IHIC look like? What narratives are being disseminated and why? Which oral histories are transmitted and which ones are marginalized? Is the government of Japan respecting the pledge made in 2015 to UNESCO to disclose the full history behind each newly listed World Heritage site? The first section starts with a detailed description of my visit to the IHIC and the contents of its guided tour. Next I offer background information on the establishment of the IHIC and the pledge made in 2015 by the Japanese government to UNESCO. The third section goes back to the IHIC guided tour, specifically to the history of Hashima Island and the revisionist narratives being disseminated during the experience. Building on this, the next two sections present in detail the differences between the testimonies of the mostly Japanese people showcased at the IHIC and those of the Koreans and Chinese who were mobilized to work in the Hashima coal mine. The reasons behind these differences and the debates surrounding oral histories are discussed accordingly. Then, to better understand why the IHIC is disseminating such revisionist narratives, I introduce Katō Kōko, the Managing Director of the IHIC` and a central figure in the historical revisionist movement. The last section before the concluding remarks focuses on two booklets distributed in the last room of the IHIC, which unequivocally represent the core claims behind the establishment of the IHIC and the perspective of the Japanese government regarding histories of forced labor and wartime mobilization.

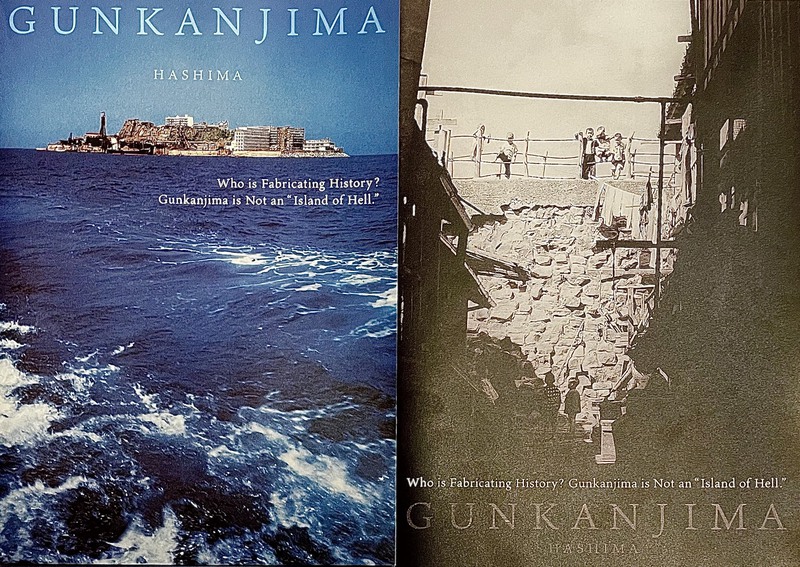

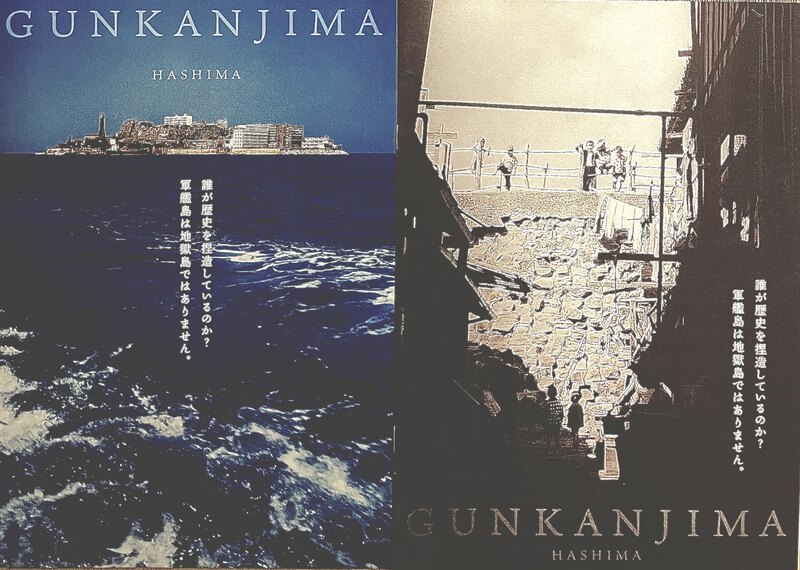

The process and motives behind the inscription of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining have already been thoroughly discussed in a two-part article by Nikolai Johnsen on the IHIC and the “pivotal figure” of Katō Kōko in promoting historical revisionism (Johnsen 2021). The official report by the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission that visited the IHIC in June 2021 is also easily accessible.1 Additionally, David Palmer has discussed Japanese nationalism and historical revisionism by focusing on the history and contemporary discourses surrounding the Hashima and Miike coal mines, both registered as World Heritage sites in 2015 (Palmer 2018, 2021). William Underwood has examined at length the issue of forced labor and reparations for Korean workers who were forcibly mobilized to work in private Japanese companies between 1939 and 1945 (Underwood 2006, 2010). Moreover, he analyzed Japan’s “quest” for World Heritage status and the lack of accountability and truth-telling by both the Japanese government and the corporations involved (Underwood 2015). Sven Saaler also discussed “history as the core of nationalism,” revisionist claims, and recent attempts to erase the knowledge and visibility the history of forced labor in Japan (Saaler 2016, 2022a,b). To summarize, existing works broadly cover the topics of nationalism, historical revisionism, dark tourism, lack of accountability, the controversies surrounding Japan’s World Heritage bid, the Hashima coal mine, and a detailed description of the IHIC. However, to my knowledge, no article or official report has talked about the guided tours conducted in Japanese at the IHIC and described its contents at length. Moreover, when reading the report by the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission, it is evident that they received a tour in English specially tailored for an audience of distinction. By contrast, I had no special treatment as I was simply one person who took part in a group tour with other Japanese people. For this reason, the guides spoke frankly, without mincing their words. Furthermore, the two booklets I received towards the end of the tour, bearing the title Gunkanjima. Hashima. Who is Fabricating History? Gunkanjima is Not an “Island of Hell”, are not mentioned in the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission report, suggesting that these booklets were not provided to the delegation. Considering the rather controversial content of the booklets, this is not particularly surprising. Additionally, this paper analyzes a variety of existing testimonies translated from Japanese and Korean in detail while covering the debates surrounding the use of oral histories. Overall, this paper favors a more deliberate narration style, paying closer attention to individual stories and the intricacies behind them as they connect to the tides of history.

Visiting the Industrial Heritage Information Center

The IHIC (sangyō isan sentā 産業遺産センター) is located in the annex of the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry’s Building No. 2. in Shinjuku, the heart of Tokyo. While it officially opened on March 31, 2020, it was not made accessible to the public until June 15 due to special measures to avoid the spread of COVID-19. The IHIC’s “About Us” page on its official English website introduces the organization as follows:

Industrial Heritage Information Centre, as a comprehensive information hub, is to support the Interpretation Strategy (submitted to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre in November 2017) for the “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding, and Coal Mining”) by closely working together with other associated visitor centers located across 11 cities in 8 prefectures.

The Information Centre is also designated as a “think-tank” that is to focus on the following matters: Documenting industrial history and heritage, both domestic and international; Research and study; Public Relations; Education & Training; Conservation and Utilization; Digital Archives; and, Information dissemination that includes industrial labor and workers’ lives.

Entrance is free of charge, but as of July 2023 prior registration is still required as a COVID-19 prevention measure. Notably, this is only mentioned in the English version of the website, while the Japanese version simply states that registration is needed. The center is open only on weekdays and offers three time slots to visit, with a maximum of 10 persons in any time slot. Upon entering, I was greeted by a young woman in a red jacket (bearing the center’s official logo) who asked me to fill in a registration form with my name, emergency telephone number, and current address. The small group waiting in the first room was immediately greeted by a first guide, an older Japanese man. The tour was meant to last around two hours, with 45 minutes for the first part, 45 minutes for the second part, and 30 minutes for questions and answers. In the first part of the tour, we were taken around Zone 1 and Zone 2, which display various panels about the late Edo period, the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in Japan in 1853, the so-called Opening of Japan, and the process of modernization and industrialization that started in the second half of the nineteenth century. The guide proudly showed us national achievements in three categories: iron and steel production, shipbuilding, and coal mining. We were not allowed to take any pictures, and the guide moved so fast that we barely had any time to read the panels. As I was jotting down as many notes as possible, a phrase from one of the few panels with an English translation caught my eye. It said: “Japan is the first non-Western nation to industrialize through a self-determined strategy.” As the tour guide pointed out, Japanese feel a sense of pride because their country, while undeniably heavily influenced by Western powers, was not colonized like China.2 The guide showed us different types of raw materials that were first used to make iron and steel, explaining the long process of trial and error that refined Japan’s traditional iron and steel-making technology and made it more suitable for industrial and military application. The guide then had us watch a video about the construction of Miike Port in Fukuoka Prefecture, on the Ariake Sea. It was used as a loading port for coal, and the guide explained the intricate work required to create its “hummingbird” shape. He also praised the construction of a new type of mechanized bulk coal loader used as an alternative to human labor.

After the first hour of the tour -which felt quite technical and slightly rushed, but clearly patriotic- we were taken to another room called Zone 3. This zone had a wall full of pictures, some chairs in the middle of the room, and a small library behind it. We were asked to sit down and another senior guide came forward, introducing himself as someone who has lived on Gunkanjima for some years.3 He started by highlighting the fact that the island used to be known only as Hashima. It is located less than 20 km away from Nagasaki Harbor and served as a coal mine until 1974, its operations managed by Mitsubishi. Hashima is now better known as Gunkanjima, which has a literal meaning of “battleship island,” because of its shape. After the mine was closed down in 1974, the island remained inhabited. Since 2009, sightseeing tours have been taking place on the island, but visitors are prohibited from venturing too close to the buildings for fear of collapse. The guide held very fond memories of the place where he lived for around three to four years between elementary and middle school. He showed us a picture of the island, explaining how it’s slightly bigger than Tokyo Dome. A local adage had it that if a kid started running from one point of the island while his dad lit up a cigarette, the kid could complete a full circle around the island before the cigarette was finished. At its peak, the island had the highest population density in Japan. The guide proudly told us that Hashima was the first place where multi-story apartment complexes were built in the country, given the lack of residences to accommodate enough workers to meet demand for coal.

What was shocking about this portion of my visit was not the guide’s fond memories of his childhood, but rather the perspectives he was trying to erase. An individual’s position in a given social hierarchy is determined by the intersections of many different layers, including but not limited to gender, ethnicity, age, physical ability, or socioeconomic status (Crenshaw 1989, Collins 2000). It is not hard to imagine Gunkanjima representing a sort of microcosm with its own hierarchy in place, where some people lived remarkably decent lives while others did not enjoy the same privileges. What is problematic is trying to impose a single point of view over all the others, implying that there can only exist a single truth. As Tessa Morris-Suzuki has eloquently explained, insisting on one “single authoritative historical truth” fails to capture the complex and interconnected nature of reality, and implies that the historian can have full access to an “objective” and “fixed” reality out there. The notion of “historical truthfulness” requires shifting the focus to “the processes by which people in the present try to make sense of the past” and realizing that narratives of the past are actively shaped by those who communicate them, by their personal ideas and interests, by the medium, and by the position we assume in the present (Morris-Suzuki 2005: 38-39). The present is actively shaped by the past and our relation to it, and thus attention must be paid to diverse representations of the past. However, even diverse representations of one event cannot convey “a perfect picture of what happened” since we cannot physically go back in time nor “enter the mental world” of other people (Morris-Suzuki 2005: 265-268). In the fraught history of Hashima Island, we can assume that available testimonies are a truthful reflection of the memories of the individual in question while also acknowledging that two people living there at the same time could have had dramatically different life experiences due to a variety of factors including gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, physical ability, and so on. Each testimony requires contextualization for us to understand how it relates to the past and present; one must also bear in mind that every narrative is inevitably shaped by the person who conveys it. It is problematic to insist that only one version of the story is true or right and other versions are lies: this is exactly what the guide repeated numerous times during the one hour we listened to him at the IHIC.

During the tour, the guide also shared the origins of the IHIC. In 2015, South Korea opposed Japan’s proposal to include Hashima and other sites as World Heritage due to the sites’ history of forced labor and wartime mobilization. UNESCO asked the two countries to find a compromise, which ultimately turned out to be Japan’s acceptance to build an information center to spread awareness about the historical events that took place on Hashima and other sites. In exchange, UNESCO recognized these locations as World Heritage Sites. The Industrial Heritage Information Center was born of this decision, but a group of former residents of the island, including the guide, took issue with its establishment because it “dishonored” the island’s name, history, and inhabitants. This group established The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts (Shinjitsu no rekishi wo tsuikyū suru Gunkanjima tōmin no kai 真実の歴史を追求する軍艦島島民の会) and contacted around seventy former residents to collect their testimonies, which can be listened to in Zone 3. Some excerpts are affixed to the walls alongside their photos; the group also established a YouTube channel under the name The Truth of Gunkanjima – Verification of Korean Conscripted Workers (Gunkanjima no shinjitsu chōsenjin chōyōkō no kenshō 軍艦島の真実 朝鮮人徴用工の検証) to share these same testimonies. To gain a more precise understanding of this story shared by the IHIC guide, I will next examine governmental communications and key developments related to this topic.

A Pledge to Remember the Victims

The World Heritage Committee officially registered the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining on its list during the 39th ordinary session in July 2015. In paragraph 4 of the document of its proceedings (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2015a), the World Heritage Committee recommended several points, including:

(g) Preparing an interpretive strategy for the presentation of the property, which gives particular emphasis to the way each of the sites contributes to Outstanding Universal Value and reflects one or more of the phases of industrialization; and also allows an understanding of the full history of each site.

According to the Summary of Records, on July 5, 2015, after concerns had been raised by the government of the Republic of Korea regarding the history of forced mobilization behind these industrial sites, the delegation of Japan delivered a statement to the Chairperson Her Excellency Professor Maria Böhmer (Germany) and Her Excellency Ruchira Kamboj (India) as follows (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2015b: 220-224):

[…] Especially, in developing the “interpretive strategy,” Japan will sincerely respond to the recommendation that the strategy allows “an understanding of the full history of each site.” More specifically, Japan is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites, and that, during World War II, the Government of Japan also implemented its policy of requisition. Japan is prepared to incorporate appropriate measures into the interpretive strategy to remember the victims such as the establishment of information center.

The Delegation of the Republic of Korea replied:

[…] The Government of the Republic of Korea has decided to join the Committee’s consensus decision on this matter, as it has full confidence in the authority of the Committee and trusts that the Government of Japan will implement in good faith the measures it has announced before this august body today.

[…] Today’s decision marks another important step toward remembering the pain and suffering of the victims, healing the painful wounds of history, and reaffirming that the historical truth of the unfortunate past should also be reflected in an objective manner.

This consensus was met with satisfaction from all parties involved, with the Chairperson stating that recognition of the sites represented an “outstanding victory for diplomacy” (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2015b: 224).

The Industrial Heritage Information Center opened to the public in June 2020 and was supposed to also commemorate the victims of forced labor, as the Japanese delegation pledged in 2015. One year later, in June 2021, a UNESCO/ICOMOS mission visited the IHIC, as the World Heritage Center had reportedly “continued to receive numerous messages expressing strong concerns about the contents of the Industrial Heritage Information Center and the implementation of the Committee’s previous decisions, including from high-level representatives of the Republic of Korea and from various NGOs” (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2021b: 4). Following this visit, the World Heritage Committee expressed “strong regret” that “the State Party has not yet fully implemented the relevant decisions” and made several requests, including (UNESCO World Heritage Committee 2021a):

(b) Measures to allow an understanding of a large number of Koreans and others brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions, and the Japanese government’s requisition policy.

The World Heritage Committee asked the government of Japan to submit an updated report on the implementation of these requests by December 1, 2022. The resulting State of Conservation Report by the Cabinet Secretariat of Japan is a sizable 577-page document, which defends the IHIC and its exhibitions, insisting that the panels already showcase the “full history” of each site. The report notes that the guiding texts will be enhanced and workers’ stories updated “as appropriate,” and that only oral histories that have been verified “to have a degree of credibility” can be included (Cabinet Secretariat of Japan 2022: 5). I visited the Industrial Heritage Information Center in early 2023, shortly after the submission of this document. Had anything changed?

Whose History?

Several of the Japanese sites registered as UNESCO World Heritage in 2015 were theaters of forced mobilization of Korean and Chinese workers or Allied POW camps in World War II. For example, the aforementioned Miike Port proudly showed off in the IHIC as “a masterpiece of civil engineering” was used to load coal extracted in Miike Coal Mine (also listed as one of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution). Managed by Mitsui, this mine not only used Korean and Chinese forced labor, but it was also the location of the largest Allied POW camp (Palmer 2021). No mention of this history appears in the Industrial Heritage Information Center, nor in the webpages dedicated to these sites.4 It is apparent that Japan’s pledge to UNESCO to take appropriate measures to remember the victims and disclose the full history of each site has not been fulfilled. This problem is closely tied to the Japanese government’s emphasis on these sites’ association with the Meiji period and the early phase of Japan’s industrialization, which, in turn, leads to the dismissal of the events that occurred in later years.

In the second part of my visit to the IHIC, I saw large photos on the wall in Zone 3, with select testimonies in the panels on the adjacent wall. The focus of this last room was fully on Hashima Island and the narratives surrounding its coal mine and forced labor. While the Industrial Heritage Information Center is ostensibly supposed to convey information about all the sites listed as World Heritage, I was surprised to see how much attention was being paid exclusively to Hashima. The previous rooms did indeed provide a general overview of the sites while carefully avoiding mentioning the “full history” behind them, as in the case of Miike. Yet the last room was devoted exclusively to Hashima and its history, which probably has to do with the strong ties between the center’s director and The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts, as will be discussed later. In this room, there was a conspicuous absence of testimonies from the Koreans or Chinese about their lives as forced laborers on Hashima, even though this was an integral part of the pledge made by Japan to the World Heritage Committee. Instead, all available testimonies were from Japanese former residents and a single second-generation Korean man, whose story will be addressed in detail. Additionally, the guide kept insisting that Korean people spread lies about forced labor and abuse, without ever mentioning Chinese people’s experiences, even though it is estimated that 204 Chinese were taken as forced laborers to Hashima.5 Of particular note is what the guide described as the “three times rule”: he explained that once the Association managed to find former residents of Hashima Island, they visited them three times. If their testimony remained consistent after three times, it would be considered to be truthful. This was allegedly an important criterion to verify the credibility of the testimonies showcased within the IHIC, as well as on their website and YouTube channel.

The guide’s explanation of why everything claimed by Koreans is a “lie”6 was quite unexpected. He proclaimed that “everyone, Japanese and Korean” lived together in the same apartment complex and shared the same bathtub (ofuro お風呂). At the time, the apartment units did not have private bathrooms or water access. Accordingly, Japanese and Koreans shared the same bathtub as well as the same classrooms in school, so it was not possible for any mistreatment to have happened. Our guide repeated this “shared bathtub” idea quite insistently as if it was a strong enough counterargument to dismiss any claims of mistreatment. Moreover, he insisted on how Japanese and Korean children “shared the same desk” at school and there was no segregation; as such, this disproved allegations of forced labor and abuse.

The shared bathtub narrative is also mentioned in a video recording in Zone 3, an NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) interview of Katō Kōko, the Managing Director of the IHIC and Executive Director of the National Congress of Industrial Heritage. The guide who showed us around is the same person sitting next to her in the NHK video. IHIC shows the full interview as a part of its exhibition because it claims that the program aired by NHK “presented the interview in a distorted way due to malicious editing.” The NHK edited broadcast, which is also shown at the beginning of the video, mentioned the pledge Japan made to UNESCO and how the narrative presented at the center glorifies wartime mobilization instead. In the full interview, Katō Kōko justified the contents exhibited at the center by saying, “I do think that it is narrow-minded to think of labor only as a negative thing.” She avoided mentioning forced labor and said instead that “the people who have worked in the mine as a family, […] taking a bath together, they are all positive to me. I think it is a wonderful life” (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021a). There are plenty of controversial claims in her statements to be unpacked. For now, it suffices to say that it is reductive and overgeneralizing to insist that sharing physical spaces is evidence of harmonious coexistence. Bullying in school, for example, happens quite often even if kids share a desk or a bathroom. In the household, domestic violence can arise among members of the same family, even if they share everything from the kitchen table to the bathtub.

In response to the testimonies of the Korean people who came forward about the abuse they suffered, the guide repeatedly said, “Aren’t they misunderstanding?” (kanchigai shiteimasenka 勘違いしていませんか). He expressed disappointment at UNESCO’s request to open an information center regarding forced labor in Hashima and emphasized how he and, by extension, The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts will never agree to “spread lies.” Complaints about the content of the panels, especially regarding the testimonies and books accumulated in the small library in the last room, have been raised first and foremost by the Republic of Korea’s Embassy in Tokyo. The embassy has criticized the IHIC’s nationalist and propagandistic motives and its neglect of information on the experiences of forced laborers (Yonhap News Agency 2022). For this reason, changes were expected to be implemented after March 2023, but the guide insisted once again that “we will not spread lies,” no matter what changes were on the horizon. At the time of my visit, the only change I noticed were two small television screens beneath the sign “work in progress” in a corner of the last room; one could infer that the existing panels will remain untouched. In any case, as long as the same group of people remains behind the management of the center and its guided tours, substantial change seems quite unlikely.

Memories of Bathtubs and Apples

In the last room of the tour, the guide started pointing to the pictures hanging on the wall, explaining how these former Japanese residents agreed to talk about their own lives and experiences and repeating the claim that no coercion or violence ever took place against Korean people. He barely gave us any time to read what was written on the panels, but the same testimonies are available on the website The Truth of Gunkanjima and their YouTube channel. On the official website, the English name appears as The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. However, The Truth of Gunkanjima – Verification of Korean Conscripted Workers represents a more literal translation of the original Japanese Gunkanjima no shinjitsu chōsenjin chōyōkō no kenshō 軍艦島の真実 朝鮮人徴用工の検証. Some examples of the testimonies available include the following people: Tada Tomohiro was born in 1926 and moved to Hashima at the end of 1945, after joining Mitsubishi Mining (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021e). Mori Yasuhiro was also born in 1926 and worked as a blacksmith on Hashima Island. He started working in the coal mine after the end of the war (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021g). Honma Hiroyasu spent part of his childhood on Hashima Island then moved to Nagasaki. He came back to Hashima in 1948 (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021c). Kobayashi Harue (1928) and Adachi Kiyoko (1933) also spent their childhood on Hashima before being evacuated to another prefecture during the war, returning to the island after its end (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021b). Matsuo Sunao was born in 1928 and spent part of his childhood in Hashima before moving away for high school and returning to the island after the end of the war (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021d). Kobayashi Teruhiko was born in 1935, went to high school in Nagasaki, and came back to work in the safety-related department of Hashima coal mine until it closed in 1974. In his interview with Katō Kōko, he was asked to comment on testimonies by Korean forced laborers, which he refuted even though he was only ten years old when the war ended. He then described at length the bathhouse he used to frequent on Hashima, insisting that Korean and Japanese families used the same bath all together (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021f). It is possible that the center’s claim that “discrimination is not possible if you share a bathtub” might have originated from this testimony.

The timeline of Matsumoto Sakae’s story, as it appears on the website, is not entirely clear (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2020a). He is the honorary president of the Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts (also called the Hashima Islanders’ Association for the Pursuit of True History)7 and one of the key members behind its foundation and expansion. He was born in 1928 and moved to Hashima in 1939. He helped his family’s tofu business until around 1943, then enlisted in the Oita Air Force until the end of the war. The description at the top of the video indicates that he worked as a surveyor in the coal mines during the war, without specifying when and why “mines” is in plural form. The video does not provide answers. Matsumoto Sakae says at the beginning of the video that he has experience working in the Hashima coal mine, but does not specify an era; he claims not to know what happened in other mines, but seems sure they were all the same. He recalls an instance where his father gifted the remaining okara (edible residue after making tofu) to some Korean workers, and in exchange they later received a box of Korean apples after the war ended. If confirmed, this could definitely be an example of kindness being reciprocated, but this one episode doesn’t mean that claims of forced labor and inhumane working conditions can be dismissed. After all, experiences on Hashima reflect the variety of people living there and the circumstances that brought them to the island.

Excerpts of testimonies from Japanese former residents feature on the wall adjacent to large-scale photos of the former residents. The guide spent quite some time on the story and testimony of Suzuki Fumio, a second-generation Korean man born on Hashima in 1933, whose father used to work as an engineer in the coal mine. Both of his parents came from Goseong County in South Gyeongsang Province, South Korea. Suzuki Fumio passed away in 2019. The video of his interview was published on the website The Truth of Gunkanjima on June 12, 2020, and is also available on the YouTube channel, published on June 15, 2020 (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2020b,c). According to this interview, his parents came to Hashima in the early 1930s and he was born there in 1933. He had a happy childhood. He doesn’t recall being discriminated against due to his Korean heritage, and he remembers feeling a sense of pride for the position of authority occupied by his father, who was known as Chief Go.8 After the war started, an accident happened in the mine. His father decided to relocate the family to Nagasaki to avoid the risk of a future accident happening to him. They received permission and left the island when Suzuki Fumio was still a child. In some clips of the same video, his eldest son Kōichi is also briefly shown remembering his father shortly after he passed away. He shared that his father always felt pride about his grandfather’s work and that he felt a sense of responsibility in giving this testimony, since he believed that the controversies surrounding Hashima indirectly impacted his family’s reputation.

It bears noting that the National Mobilization Law (Kokka sōdōin’hō 国家総動員法) was first legislated in March 1938 and took effect in May, less than one year after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, conventionally regarded as the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Beginning in 1939, because of labor shortages due to the conscription of Japanese men for the military effort, the mobilization expanded to colonized Korea as well, under increasing states of coercion (Underwood 2006). A report by a contracted employee of the Home Ministry on July 31, 1944 stated that all sorts of methods were employed, with increasing cases of forced mobilization akin to “kidnapping” or “hostage-taking” (The Center for Historical Truth and Justice, Republic of Korea, and Network for Fact Finding on Wartime Mobilization and Forced Labor, Japan 2017: 25). When Suzuki Fumio’s parents moved to Hashima in the early 1930s, their circumstances were not the same as Koreans who were forcefully mobilized after 1939. It is fortunate that his father managed to rise to a position of authority and that Suzuki Fumio didn’t recall any instances of blatant discrimination during his early childhood. However, this does not indicate that everyone else experienced the same. Moreover, he never set foot in the coal mine, so his memories are necessarily different from those who had direct experience with mining. It would have been interesting to hear the story of Suzuki Fumio’s father and his rise to a leadership role in the coal mine, but now it is impossible to inquire further about firsthand experiences due to the passage of time. In any case, we can assume that Suzuki Fumio’s testimony has been truthful to his own experience as a child who spent some years in Hashima, and that he lived a comparatively more privileged life thanks to his father’s status. However, just like Suzuki Fumio’s words are truthful to his life experience, the words of other Koreans who gave testimonials of different experiences need to be heard and understood, particularly those who had direct experience of working in the coal mine.

The guided tour at the Industrial Heritage Information Center was especially problematic because every testimony displayed on the wall was used as proof that testimonies expressing other points of view are all “lies” being spread to “dishonor Hashima and its inhabitants.” The testimonies of the Japanese former residents reflect their childhood memories, and their recollections sound nostalgic because they didn’t face any form of discrimination based on their ethnicity. Awareness of social injustices is inevitably limited at a young age, particularly if one is part of the majority. Moreover, they did not have personal work experience in the mine during wartime. One point still demands further attention: were victims and survivors of forced labor motivated to speak up to dishonor Hashima and its former inhabitants?

Experiences of Mobilized Workers

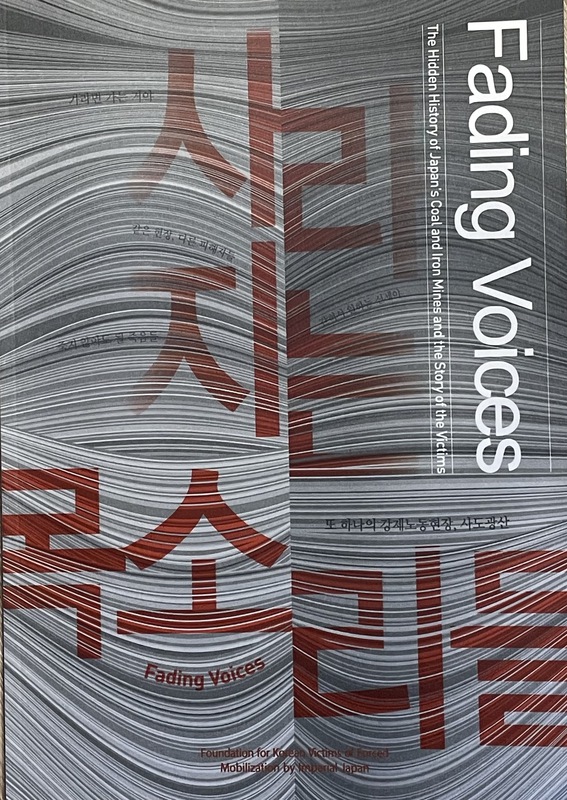

The National Memorial Museum of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Occupation in Busan, Korea offers quite a different narrative of forced labor than the IHIC. Volume 18 of their magazine mentions a report of the Government of Korea confirming more than 800 forced mobilization workplaces in Kyushu and in Yamaguchi Prefecture, where 37,400 laborers were mobilized and around 2,500 died (National Memorial Museum of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Occupation Magazine (FoMo) 2021: 9). Between 500 and 800 Koreans are said to have been mobilized to Hashima, of which 121 never returned (Hankook Ilbo, JoongAng Ilbo 2017).9 According to Japanese researcher Takeuchi Yasuto, approximately 1,000 Korean laborers were taken to Hashima, with 122 recorded deaths. Of these, at least 27 deaths were confirmed to have been related to reprehensible living and working conditions (Johnsen 2021a: 8). According to the booklet Fading Voices, The Hidden History of Japan’s Coal and Iron Mines and the Story of the Victims, 136 Korean and Chinese deaths were recorded between 1925 and 1945 in “The Cremation Permits and Accident Report (Nagasaki).” Based on cremation applications and permits, we know the victims’ names, ages, occupations, and cause of death: 30% of Koreans died from diseases, 14% from injuries, 26.1% from accidents (including injuries and coal mine accidents), 18.5% from collapse deaths (including crushing and suffocation), and 10.9% from other causes (The Center for Historical Truth and Justice 2022).

The booklet Fading Voices, The Hidden History of Japan’s Coal and Iron Mines and the Story of the Victims (사라지는 목소리들 – 석탄과 철에 은폐된 역사 그리고 희생자의 이야기) is available at the Museum of Japanese Colonial History (식민지역사박물관) in Seoul, South Korea. This picture was taken by the author.

Several other voices have been recorded and presented in journal articles, starting from the story of Choi Jang-seop. He was born in 1929 in Iksan, North Jeolla Province, South Korea. In February 1943, he and other four boys were forcefully conscripted by recruiters as “wartime mobilization laborers” (jeonsi dongwon nomuja 전시 동원 노무자). He was taken to Hashima when he was fourteen years old, stripped of his belongings and even of his Japanese name, Yamamoto. From that point forward, he was instead referred to by the number 6105. According to Choi Jang-seop, the Korean forced laborers had to work long shifts, sometimes more than twelve hours, and could only wear their loin cloths. They were considered dirty because their bodies were blackened by the coal. Food was scarce and working conditions unsafe; he was once injured in a cave-in. Escape or rebellion would simply result in his being beaten with a rubber whip, as he personally experienced. In his autobiography, he recalled how “the miners suffered from starvation, were covered in sweat all year around, and had cramps in their legs due to malnutrition. Several people collapsed every day. Labor was hard. Still, we had to live on three lumps of soybean meal a day. I couldn’t stand it no matter how hard I tried” (The Center for Historical Truth and Justice 2022: 15). All the Korean conscripts had to live at the bottom of the apartment buildings where there was poor natural light, and screams of pain could be heard at all times. People would etch phrases on the wall like “I want to see my mother,” “I am hungry,” or “I want to go home” (Hankook Ilbo 2017). As one of the most well-known victims and survivors, Choi Jang-seop has spoken publicly numerous times about his experiences in Hashima. He remembers feeling enraged at the news of Hashima being recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2015, especially knowing that the Japanese government does not honor nor acknowledge the Korean victims among the mine workers who lived on the island (Hankook Ilbo 2017).

Lee In-woo was born in Daegu,10 the eldest of seven siblings: two sons and five daughters. His younger brother was blind in one eye, and their father was a poor farmer. He recalls dreading the constant state of hunger they were in, so he decided to leave for Japan after hearing from recruiters that he could make a lot of money there. He was put on a cargo ship departing from Busan in May 1944 and arrived in Sakhalin to work in the coal mines for a few months. In the winter, he was moved to Hashima without being given a reason. He shared a room with five other people, and they all worked twelve-hour shifts wearing only loin cloths, traveling 1,000 meters underground to work in the coal mine. He remembers being put to work with Chinese people, but because he couldn’t understand the Chinese language, the work was really slow and he was often physically abused by the overseers. Death and injuries were a daily occurrence, and he remembers the smell of bodies being cremated. He said he earned a meager amount that provided him with basic necessities. In July 1945, he was transferred to a place near Hiroshima and trained to carry bombs to use against the Allied Powers. After hearing about Japan’s surrender, he thought it was a miracle that he survived. He was able to go back to Korea, and then to his family on August 27 (JoongAng Ilbo 2017).

As can be seen from the testimonies above, the living and working conditions in Hashima during the last years of the war, as recounted by Choi Jang-seop and Lee In-woo, seem to have been quite different from the memories of second-generation Korean resident Suzuki Fumio. The obvious explanation for this discrepancy is that Choi Jang-seop and Lee In-woo had direct experience of the work in the coal mine, while Suzuki Fumio never set foot there. A second reason lies in their different circumstances: Suzuki Fumio’s family came to Hashima before forced mobilization was enacted, and when the socioeconomic and political situation was completely different compared to the 1940s. In the same testimony reported by Hankook Ilbo, Choi Jang-seop explained why he decided to publicly recount his painful past experiences: “There are people like me who have suffered through bitter pain and remember it to this day. I hope Japan will no more bring pain to others, and regain its conscience.”11 In essence, the core of this whole discourse is not about honoring or dishonoring Hashima and its inhabitants, but about individual and collective pain and how victims and survivors cannot find a sense of closure if institutions in Japan keep denying having committed any wrongdoing.

Forced laborers in the Hashima coal mine were not all Korean. Due to increasing labor shortages, Chinese POWs were also brought to Japan and subjected to the same hard working conditions. For example, Li Qing Yun from Hebei Province joined the Eight Army Route in 1942 but was captured by the Japanese Army in November 1943. He was moved to a concentration camp before being sent to work in the Hashima coal mine, working twelve-hour shifts and living in a cramped room with forty to fifty people. They, too, could only wear loincloths. Li Qing Yun was forced to work even when sick, or otherwise his meager food rations would be reduced. Violence and punishments were a daily occurrence (The Center for Historical Truth and Justice, Republic of Korea, and Network for Fact Finding on Wartime Mobilization and Forced Labor, Japan 2017: 29-30; Nagasaki zainichi Chōsenjin no jinken wo mamoru kai 2016). According to the report titled “Investigative Report on the Situation Concerning the Use of Chinese Laborers” (Kajin rōmusha shūrōjijō chōsa hōkokusho 華人労務者就労事情調査報告書) by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs written in 1946, 38,935 Chinese people were mobilized in 135 sites across the country from April 1943 to June 1945. Of these, 6,830 died. A total of 3,896 were sent to places that are today recognized as World Heritage Sites, including 409 sent to Mitsubishi’s Takashima coal mine (The Center for Historical Truth and Justice, Republic of Korea, and Network for Fact Finding on Wartime Mobilization and Forced Labor, Japan 2017: 28-29; Underwood 2005) and an estimated 204 to the Hashima coal mine (Takeuchi 2018 mentioned in Johnsen 2021a: 20). For some reason, the guide at the IHIC never mentioned Chinese laborers and focused only on Korean survivors’ testimonies, labeling them all as lies. Even the two booklets handed to us, entitled Gunkanjima. Hashima. Who is Fabricating History? Gunkanjima is Not an “Island of Hell,” mainly centered on Koreans and their “baseless rumors.”

Spotlight on the Center’s Director: Who is Katō Kōko?

The guided tour at the Industrial Heritage Information Center ended up taking two full hours, so there was basically no time for questions and answers. Even though there were no other groups, we were not given any extra time. As we were being escorted towards the exit, someone quickly asked what evidence the IHIC has that no mistreatment ever occurred, apart from these select testimonies. The guide became tense and defensive, and said that we should just come back and look at the material on their computer more thoroughly. When it was pointed out that the computer contains the same testimonies, plus some historical documents without much contextualization, a guard came over and asked everyone to leave. We were given several booklets to take home, available in Japanese and in English (all without publication dates), including a general guidebook on the sites of the industrial revolution of the Meiji period and maps that can be connected to a car navigation system, in case we might like to visit these sites in person. The backside of the guidebook indicated that it was written and overseen by Katō Kōko, the Managing Director of the IHIC and Executive Director of the National Congress of Industrial Heritage (NCIH), and published by the World Heritage Council for the “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” and the Secretariat of the World Cultural Heritage Division, Kagoshima Prefectural Government. Additional publications are available to read on the Japanese version of the center’s website, but it is not permitted to reproduce their content.12

Who is Katō Kōko? A two-part article written by Nikolai Johnsen explained in detail how she has been the “pivotal figure” behind the process of registering the 23 Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution to the World Heritage List. Her family has long-lasting ties with the family of former prime minister Abe Shinzō. Her father Katō Mutsuki was the right-hand man of Abe Shinzō’s father, Abe Shintarō (Johnsen 2021a: 9). Abe Shinzō was notorious for his revisionist views on Japan’s modern history and responsible for the increasing censorship of history textbooks, beginning with the revision of the Fundamental Law of Education in 2006. Under immense political pressure and out of fear that their manuscripts might be rejected by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), publishers are self-censoring textbooks by avoiding mention of any potentially controversial topic, including military sexual slavery, forced labor, and war crimes like the Rape of Nanking or the experiments conducted by Unit 731.13 Given the right-wing, LDP-led political environment he promoted, it is no surprise that Abe Shinzō was very supportive of Katō Kōko’s efforts to inscribe Japan’s Meiji Industrial Sites as World Heritage, both of them refusing to acknowledge any claims of forced labor or abuse.

The long process of registering these 23 sites was initiated in 1999 and completed in 2015, which Nikolai Johnsen has thoroughly documented (Johnsen 2021b). Still, it is important to highlight how central Katō Kōko was as UNESCO’s direct contact and as executive director of the NCIH, which is responsible for collecting materials for the exhibitions at the IHIC. The NCIH is a private foundation, not an official research institution, yet it has received conspicuous amounts of government funding. Many of its key members have potential conflicts of interest, given that they are representatives of companies like Mitsubishi or Nippon Steel, which managed or still operate some of the industrial sites that had forced laborers. Against this background, it is not surprising that the IHIC has followed a trajectory of historical revisionism, cherrypicking evidence in order to construct and disseminate a narrative that silences the victims while celebrating the “uniqueness” of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution (Johnsen 2021b: 1-6).

In response to the report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission to the Industrial Heritage Information Center, Katō Kōko wrote on August 4, 2021 on The Truth of Gunkanjima website:

We reject the implication made at the time of listing and subsequently that Korean workers were ‘victims’ because their labor was the result of gross infringements of human rights. This was demonstrably not the case. The interpretation of history ought to be based on primary historical documents and testimonies, not on “politics” or “movements,” and if there are 100 researchers, there will be 100 different interpretations of history. The role of the Information Centre should be to provide accurate primary sources, leaving the interpretation to the individual researcher (The Truth of Gunkanjima 2021h, direct quote).

It is difficult to overlook the irony of Kato proclaiming that history should not be based on politics, in light of her close connections to the LDP and big businesses. Moreover, the IHIC displays a one-dimensional narrative rather than a comprehensive selection of available testimonies and historical documentation from all sides, essentially implying that there is only one possible interpretation of their material.

Katō Kōko has personally written and overseen the production of the official guidebook and maps that do not mention forced labor at all, presenting a sterilized version of the sites’ history. Additionally, she took part in the publication of the booklets prepared by The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts in cooperation with the NCIH, which I present in detail in the next section. Unlike the official guidebook, these booklets are entirely focused on the claim that forced labor and abuse never took place, labeling proofs of the contrary as “lies” that aim to “distort historical facts.” These booklets unequivocally reveal the personal views of those in charge of the IHIC and those who conduct the guided tours. They clearly show that the IHIC has been designed with a specific narrative in mind, one that does not remember the victims by disclosing the “full truth” of each site, as promised to UNESCO.

Who is Fabricating History?

When we were taken to Zone 3, the last room of the tour, with the second guide, we were given two extra booklets14 available in English and Japanese published by The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts in cooperation with the NCIH.15 Both bear the same title Gunkanjima. Hashima. Who is Fabricating History? Gunkanjima is Not an “Island of Hell,” but with different alignments. The only way to easily distinguish them is by the cover: one shows a more recent picture of Hashima Island and its ruins (hereafter Booklet A), while the other shows a black-and-white photograph of daily life in the past (hereafter Booklet B). Neither lists a date of publication, but both reproduce and critique news articles, museum texts, and exhibitions that describe the experiences of forced laborers up to June 2020. Booklet B, in particular, criticizes the numbers reported in news outlets of Koreans and Chinese who passed away due to accidents or work-related conditions in the Hashima coal mine. It concludes with a page titled “A Spirit of Mutual Aid Across Lines of Ethnicity,” which reports two instances wherein a Japanese worker became trapped in a cave-in with other Korean or Chinese workers and managed to escape by cooperating with them. As I read the full report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission that took place in June 2021, I couldn’t find any mention of these booklets. They were not part of the materials photographed and reproduced in Annex 8 of the same document. Because the information in the booklets only goes up to June 2020, it is possible that they might have been published around that time. Apparently they were not been distributed to the mission’s members, perhaps due to their controversial content.

Booklets in English and Japanese distributed at the IHIC, Zone 3, published by The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts in cooperation with the National Congress of Industrial Heritage (no publication date).

It is quite problematic that booklets bearing a title like Gunkanjima. Hashima. Who is Fabricating History? Gunkanjima is Not an “Island of Hell” are being casually distributed in a center that was established in accordance with UNESCO guidelines in order to spread awareness regarding forced laborers and their experiences. The center’s “About Us” page on its official website describes its activities as those of a think tank, with a focus on “information dissemination that includes industrial labor and workers’ lives.” After visiting the center and reading their materials, I concluded that their “information dissemination” follows a precise direction that is closer to propaganda and historical revisionism than a comprehensive analysis of diverse experiences and an earnest attempt to understand the mechanisms behind them. The words of the tour guides also leave no room for misunderstanding their intentions.

The language used in the general guidebook Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution is notably more generic compared to the two booklets. The former provides an overview and brief history of important sites for iron and steel, coal mining, and shipbuilding, and the coal mines on Hashima and Takashima Islands are mentioned on pages 17 and 18. The guidebook offers a brief description of the undersea coal deposits, coal output, and population density of the islands without ever going into detail about working and living conditions. By contrast, the two booklets titled Gunkanjima. Hashima. Who is Fabricating History? Gunkanjima is Not an “Island of Hell” focus exclusively on Hashima and the “inexcusable distortion of facts” (Booklet B: 2) perpetrated by foreign news agencies, museums, civic groups, and so on. Booklet A opens with a statement by The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts, describing how “proud” they felt when Hashima was inscribed on the World Heritage List as one site of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. However,

During the process of inscription, our hearts were broken by the repeated slandering and defamation of Hashima by the Government and civic groups of the Republic of Korea.

[…] As former residents of the island, we feel that our human rights have been violated by the words “abused” and “murdered” by Korean groups to discredit Hashima. We cannot forgive the groups and activists who repeat these baseless rumors (Booklet A: 3).

Katō Kōko and The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts are not alone in trying to disseminate this narrative. An article published in Japan Forward (a news website known for its right-wing stance) described the Industrial Heritage Information Center as follows:

Written testimonies about the lives of people from the Korean Peninsula during World War II are also on display. Some of the exhibits show the reality of Koreans in wartime Japan, working at the Hashima coal mine on the Hashima Island, commonly known as “Gunkanjima” (Battleship Island), in Nagasaki prefecture. (Japan Forward 2020)

At the time of my visit almost three years after this article had appeared, no testimonies about the lives of Korean people were on display. All the testimonies were from Japanese former residents of Hashima, except the second-generation Korean Suzuki Fumio. The article was written by Okuhara Shimpei, who is a writer for the Sankei Shimbun. On July 7, 2020, an opinion piece was published in Sankei Shimbun by Sasaki Rui, the Vice Chairman of the Editorial Board. The article recounted his visit to the Industrial Heritage Information Center on June 25, and he described at length about the testimony of Suzuki Fumio and the words uttered by his eldest son Kōichi, specifically the “groundless lies” (nemo hamo nai uso 根も葉もない嘘) about Korean forced labor that tarnished the reputation of his father and grandfather. The testimony of Suzuki Fumio and his eldest son can be viewed on the computer inside the center, on the website The Truth of Gunkanjima, and on the YouTube channel of the same name. Sasaki then continued with his view that these “groundless lies are claims by the Republic of Korea that are not based in reality.” He mentioned the South Korean Embassy’s visit to the IHIC and their frustration over the erasure of the victims, but nonetheless concluded by stating his agreement with these words from Katō Kōko:

It’s a problem of reception from the visitor’s side. I want visitors to see reality as it is in its multifaceted way (Sankei Shimbun 2020, author’s translation).

Reality is indeed multifaceted, and no individual’s experience is the same as another. Their experience must be contextualized and understood in all of its complexities. But it seems like the historical narrative of the Industrial Heritage Information Center has been crafted for the exact opposite reason—to promote a one-dimensional narrative.

Concluding Remarks

Oral histories are based on one’s own experiences, and it is only natural that no two are alike. Suzuki Fumio’s testimony reflects his memories of his childhood years spent in Hashima, in the same way that the testimonies of Choi Jang-seop and Lee In-woo are reflective of their own life stories. While their narratives differ greatly, this discrepancy can be explained by looking at the circumstances of their lives: Choi Jang-seop was taken to Hashima under the National Mobilization Law in 1943 when he was 14 years old. He arrived in Hashima alone, taken away from his family when the war was already in full swing. Lee In-woo was desperate and lured by promises of recruiters, taken first to Sakhalin and then to Hashima in 1944 or 1945. He quickly realized that the promised wage and the working conditions were nothing like he was told, but he could not escape. By contrast, Suzuki Fumio was born in 1933, and his parents had decided to move to Hashima a couple of years prior. They enjoyed better living conditions and his family obtained permission to leave the island before the war started turning against Japan. Overall, their situation differed greatly from those who were mobilized after 1939.

What is problematic is the attempt by The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts, the National Congress of Industrial Heritage, and the Industrial Heritage Information Center, led by Katō Kōko and her powerful supporters, to refute the testimonies and historical documentation that do not fit their one-dimensional political agenda. After visiting the center, listening to the two-hour-long tour in Japanese, and reading their booklets, I understood clearly that they are trying to disseminate a narrative where no mistreatment or abuse ever happened by relying on the select testimonies of former Japanese residents who spent their childhood on Hashima. Listening to these stories, one can feel how dearly they hold the memories of their families and their lives on the island. This much is understandable. After all, very few people have an easy experience of war; they all have lost something or someone. The intent of this article is not to discredit their stories, but to demonstrate how their testimonies are used to erase the stories of other people who had different experiences.

The “three-time rule” to confirm the credibility of oral testimonies of former Hashima island residents is also incompatible with claims that testimonies of former forced laborers or victims of military sexual slavery should not be trusted.16 Historical revisionists completely refute the words of victims and survivors whose experiences do not fit their political agenda, saying that memories are too vague and unreliable. Documents, too, need to be understood in their historical context, and victims/survivors still often bear the scars from the abuse they endured, but revisionists choose to ignore this.17 Yet when it comes to supporting revisionist claims, oral testimonies, such as those presented in the IHIC or on the website The Truth of Gunkanjima, are placed in the spotlight and offered as reliable sources. This double standard clearly violates the rules of academic historical research and, first and foremost, the victims’ experiences. From the testimonies of former Hashima Island residents, it is evident that some people and their families had been fortunate enough to avoid blatant racial discrimination and abuse, even if they struggled in other ways. They might even have shown acts of kindness towards Korean and Chinese laborers, but this doesn’t automatically erase the pain of other people and their families. Historians in and outside of Japan have accumulated ample evidence of forced labor and abuse. Therefore, to claim that similar testimonies are “groundless lies” is contrary to historical facts established by historians. In order to fulfill the pledge made to UNESCO in front of the representative of the Republic of Korea, the IHIC and the Cabinet Secretariat of Japan should take appropriate measures to disclose the “full history” behind each World Heritage Site and showcase a wide range of available testimonies, including those of Koreans, Chinese, and Allied POW. The IHIC should strive not to push one “truth” over another in a zero-sum game, but to comprehensively portray the multifaceted nature of reality, even if this means tackling some of the darker chapters of Japan’s modern history.

References

Arirang News. 2017. ‘The Dark History of Conscription and Forced Labor Behind Japan’s Hashima Island.’ YouTube, 5 July. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCH6VdyuxGU&list=PL1sIgKU1FHchvm0lgHMN5Rp_D_3m5psN4&index=22&t=205s

Cabinet Secretariat of Japan. 2022. ‘State of Conservation Report by the State Party.’ https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/sangyousekaiisan/seikaiisan_houkoku/pdf/221130/siryou_en02.pdf

Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. ‘U.S. Black Feminism in Transnational Context.’ In Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 227-250. New York: Routledge.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.’ University of Chicago Legal Forum: 139-167.

Dezaki, Miki, director. 2019. Shusenjo: The Main Battleground of the Comfort Women Issue.’ No Man Productions LLC.

Foundation for Supporting Victims of Forced Mobilization by Japan 일제강제동원피해자지원재단. https://www.fomo.or.kr/kor

Industrial Heritage Information Center 産業遺産情報センター. ‘About Us.’ Last accessed July 5, 2023. https://www.ihic.jp/l/en-US/about-us

Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution 明治日本の産業革命遺産. ‘人材育成 [Human Resource Development]’. Last accessed July 6, 2023. http://www.japansmeijiindustrialrevolution.com/conservation/interpretation.html

Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. ‘Miike Coal Mine.’ Last accessed July 5, 2023. http://www.japansmeijiindustrialrevolution.com/en/site/miike/component01.html

Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. ‘Miike Port.’ Last accessed July 5, 2023. http://www.japansmeijiindustrialrevolution.com/en/site/miike/component02.html

Jeong, Hi-jeong 鄭憙靖 정희정. 2022. ‘韓国政府 日本の明治産業遺産巡る約束不履行に「遺憾」 [South Korean Government express “regret” over Japan’s failure to fulfill its promise regarding Meiji Industrial Heritage].’ Yonhap News Agency, 13 December. https://jp.yna.co.kr/view/AJP20221213004100882

Johnsen, Nikolai. 2021a. ‘Katō Kōko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution – Forgetting forced labor to celebrate Japan’s World Heritage Sites – Part 1.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 19 (23): 1-19. https://apjjf.org/2021/23/Johnsen.html

Johnsen, Nikolai. 2021b. ‘Katō Kōko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution – Forgetting forced labor to celebrate Japan’s World Heritage Sites – Part 2.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 19 (24): 1-17. https://apjjf.org/2021/24/Johnsen.html

JoongAng Ilbo 중앙일보. 2017. ‘[단독]”지하 1000m 갱도에서 동료 죽음 지켜봐“…군함도 징용 생존자 이인우 옹 인터뷰 [Exclusive: “Witnessing my fellow workers’ death in a 1000m underground mine”… Interview with Lee In-woo, a survivor of the conscription on Battleship Island].’ 10 August. https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/21834008#home

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. 2005. The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History. London: Verso. Kindle edition.

Nagasaki zainichi Chōsenjin no jinken wo mamoru kai 長崎在日朝鮮人の人権を守る会. 2016. 軍艦島に耳を澄ませば –端島に強制連行された朝鮮人・中国人の記憶 [If You Listen Carefully to Gunkanjima: Records of Korean and Chinese Forced into Labor at Hashima]. Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha.

National Congress of Industrial Heritage 産業遺産国民会議. ‘National Congress of Industrial Heritage 産業遺産国民会議’. New website. Last accessed July 6, 2023. https://www.ncih.jp/ncih

National Congress of Industrial Heritage 産業遺産国民会議. ‘出版物 [Publications].’ Old website. Last accessed July 6, 2023. https://sangyoisankokuminkaigi.jimdo.com/出版物/

National Memorial Museum of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Occupation 국립일제강제동원역사관. 2021. 포모(FoMo) 소식지 [FoMo Magazine] vol. 18. https://www.fomo.or.kr/museum/kor/CMS/Board/Board.do?mCode=MN0094&&mode=view&board_seq=2752&

Nozaki, Yoshiko. 2000. Textbook Controversy and the Production of Public Truth: Japanese Education, Nationalism, and Saburo Ienaga’s Court Challenges. PhD diss. The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Okuhara, Shimpei. 2020. ‘Spotlight on Japan’s Industrial Heritage, Wartime Past at Newly-Opened Information Center.’ Japan Forward, 26 June. https://japan-forward.com/spotlight-on-japans-industrial-heritage-wartime-past-at-newly-opened-information-center/

Palmer, David. 2018. ‘Gunkanjima / Battleship Island, Nagasaki: World Heritage Historical Site or Urban Ruins Tourist Attraction?’ The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, 16 (1): 1-25. https://apjjf.org/2018/01/Palmer.html

Palmer, David. 2021. ‘Japan’s World Heritage Miike Coal Mine – Where prisoners-of-war worked “like slaves”.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 19 (13):1-27. https://apjjf.org/2021/13/Palmer.html

Saaler, Sven. 2016. ‘Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal 14 (20): 1-17. https://apjjf.org/2016/20/Saaler.html

Saaler, Sven. 2022a. ‘Demolition Men: The Unmaking of a Memorial Commemorating Wartime Forced Laborers in Gunma (Japan).’ The Asia-Pacific Journal 20 (16): 1-27 . https://apjjf.org/2022/16/Saaler.html

Saaler, Sven. 2022b. ‘Japan’s Soft Power and the “History Problem”.’ In Remembrance–Responsibility–Reconciliation: Challenges for Education in Germany and Japan, eds. Lothar Winger, Marie Dirnberger, 45-66. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Saika, Hisayo 斉加 尚代. 2022. 教育と愛国 [Education and Patriotism]. Mainichi Broadcasting System.

Sasaki, Rui 佐々木類. 2020 ‘ありのままを見てほしい [I Want You to See Reality As It Is].’ Sankei Shimbun, 7 July. https://www.sankei.com/article/20200707-MXLLH6LS3NJBND6OSHGFPRB25U/

Shin Hye-jeong 신혜정. 2017. ‘ “포로생활보다 더 끔찍” 최장섭 옹의 ‘군함도 3년10개월’ [“More terrible than life in captivity.” Choi Jang-seop’s ‘3 years and 10 months on Battleship Island’].’ Hankook Ilbo 12 August. https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201708120944500841

Takeuchi Yasuto 竹内 康人. 2018. 明治日本の産業革命遺産 強制労働 Q&A [Meiji Japan’s heritage of the industrial revolution Forced labor Q&A]. Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha.

The Association of Hashima Island Residents for the Pursuit of Historical Facts, and the National Consortium of Industrial Heritage (NCIH). Gunkanjima. Hashima. Who is Fabricating History? Gunkanjima is Not an “Island of Hell”. The two booklets were distributed at the Industrial Heritage Information Center 産業遺産情報センター in Tokyo, Japan.

The Center for Historical Truth and Justice, Republic of Korea, and Network for Fact Finding on Wartime Mobilization and Forced Labor, Japan. 2017. Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution and Forced Labor: Korea-Japan NGO Guidebook. This guidebook is available at the Museum of Japanese Colonial History 식민지역사박물관 in Seoul, South Korea.

The Center for Historical Truth and Justice. 2022. 사라지는 목소리들 – 석탄과 철에 은폐된 역사 그리고 희생자의 이야기 [Fading Voices, The Hidden History of Japan’s Coal and Iron Mines and the Story of the Victims]. This booklet can be obtained at the Museum of Japanese Colonial History 식민지역사박물관 in Seoul, South Korea.

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2020a. ‘Mr. Sakae Matsumoto, former resident of Hashima Island.’ 23 September. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Mr-Sakae-Matsumoto-former-resident-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 軍艦島の真実 朝鮮人徴用工の検証. 2020b. ‘端島元島民 鈴木文雄さん [Mr. Fumio Suzuki, former resident of Hashima Island].’ 12 June. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/ja-JP/article/端島元島民–鈴木文雄さん

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 軍艦島の真実 朝鮮人徴用工の検証. 2020c. ‘端島元島民 鈴木文雄さん [Mr. Fumio Suzuki, former resident of Hashima Island].’ YouTube, 15 June. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B3u2lWgtDII&t=780s

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 軍艦島の真実 朝鮮人徴用工の検証. 2021a. ‘(English sub)NHK “Realization!! (Do! Do! Do!) Koko Kato’s full version of the interview with NHK.’ YouTube, 2 April. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKo4r7DvLRA

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021b. ‘Ms. Harue Kobayashi and Ms. Kiyoko Adachi, both former residents of Hashima Island.’ 28 May. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Ms-Harue-Kobayashi-and-Ms-Kiyoko-Adachi-both-former-residents-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021c. ‘Mr. Hiroyasu Honma, a former resident of Hashima Island.’ 25 May. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Mr-Hiroyasu-Honma-a-former-resident-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021d. ‘Mr. Sunao Matsuo, a former resident of Hashima Island.’ 25 May. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Mr-Sunao-Matsuo-a-former-resident-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021e. ‘Mr. Tomohiro Tada, a former resident of Hashima Island.’ 28 May. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Mr-Tomohiro-Tada-a-former-resident-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021f. ‘Mr. Teruhiko Kobayashi, a former resident of Hashima Island.’ 24 May. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Mr-Teruhiko-Kobayashi-a-former-resident-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021g. ‘Mr. Yasuhiro Mori, a former resident of Hashima Island.’ 25 May. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/Mr-Yasuhiro-Mori-a-former-resident-of-Hashima-Island

The Truth of Gunkanjima – Testimonies to Conscripted Korean Workers. 2021h. ‘UNESCO Decision and UNESCO-ICOMOS Expert Report.’ 4 August. https://www.gunkanjima-truth.com/l/en-US/article/UNESCO-Decision-and-UNESCO-ICOMOS-Expert-Report

Underwood, William. 2005. ‘Chinese Forced Labor, the Japanese Government and the Prospects for Redress.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal 3 (7): 1-10. https://apjjf.org/-William-Underwood/1693/article.html

Underwood, William. 2006. ‘Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages (1): Reparations for Korean Forced Labor in Japan.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 4 (9): 1-25. https://apjjf.org/-William-Underwood/2219/article.html

Underwood, William, Kim Hyo Soon, and Kil Yun Hyung. 2010. ‘Remembering and Redressing the Forced Mobilization of Korean Laborers by Imperial Japan 日帝による朝鮮人労働者の強制動員を記憶にとどめ是正する方向.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 8 (7):1-13. https://apjjf.org/-William-Underwood/3303/article.html

Underwood, William. 2015. ‘History in a Box: UNESCO and the Framing of Japan’s Meiji Era 「箱入り」歴史 ユネスコと明治期の位地づけ.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus 13 (26): 1-13. https://apjjf.org/William-Underwood/4332.html

Underwood, William, and Mark Siemons. 2015. ‘Island of Horror: Gunkanjima and Japan’s Quest for UNESCO World Heritage Status.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal 13 (26): 1-5. https://apjjf.org/Mark-Siemons/4333.html

UNESCO/ICOMOS. 2021. ‘Report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS Mission to the Industrial Heritage Information Centre Related to the World Heritage Property ‘Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Ship-building and Coal Mining’ (Japan) (c1484), 7 to 9 June 2021.’ https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/188249

UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 2015a. ‘Decision 39 COM 8B.14 Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining, Japan.’ https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/6364/#_ftnref1

UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 2015b. ‘Thirty-ninth session Bonn, Germany 28 June – 8 July 2015. Summary of Records,WHC.15 /39.COM /INF.19.’ https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2015/whc15-39com-INF.19.pdf

UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 2021a. ‘Decision 44 COM 7B.30, Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining (Japan) (C 1484).’ https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/7748/

UNESCO World Heritage Committee. 2021b. ‘Item 7B of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. Extended forty-fourth session Fuzhou (China) / Online meeting 16-31 July 2021.’ https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2021/whc21-44com-7B.Add2-en.pdf

World Heritage Council for the “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” and the Secretariat of the World Cultural Heritage Division, Kagoshima Prefectural Government. Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. Guidebook distributed at the Industrial Heritage Information Center 産業遺産情報センター in Tokyo, Japan.

Notes

The full report of the mission, published on July 2, 2021, can be downloaded here: https://whc.unesco.org/document/188249. The report includes a map of the three zones of the IHIC, as well as pictures of the exhibitions and materials available inside (Annex 8).

China was indeed subjected to colonial incursions, although the country was largely able to protect its independence and territorial integrity, save for the significant exceptions of foreign concessions in cities like Shanghai, not to mention the establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo in the early 1930s.

The guide’s name tag read as Nakamura Yōichi. He is the same guide mentioned in the article by Japan Forward that will be discussed at the end of this paper, and his photograph also appears on page 52 of the report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission at the IHIC that took place in June 2021. He is referred to as Chief Guide.

Each site listed as World Heritage, part of Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution, has its own webpage dedicated to spreading information about each location. See webpages for Miike Coal Mine (http://www.japansmeijiindustrialrevolution.com/en/site/miike/component01.html) and for Miike Port (http://www.japansmeijiindustrialrevolution.com/en/site/miike/component02.html). This website and its contents are directed by Katō Kōko. Last accessed July 5, 2023.

Takeuchi Yasuto, 明治日本の産業革命遺産 強制労働 Q&A [Meiji Japan’s heritage of the industrial revolution Forced labor Q&A] (Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha, 2018), p.20, mentioned in Johnsen, 2021a.

Claiming that Koreans are “liars” is quite common among historical revisionists. This has been discussed for example in Saaler, 2022b. In the case described by Saaler, Yamamoto Yumiko (the president of the Nadeshiko Action Group and former member of the Zaitokukai, a racist and anti-Korean association) wrote on October 30, 2020, a letter to the mayor of Berlin-Mitte district asking to remove the statue recently erected to commemorate “comfort women.” “Lying is a special skill of Koreans,” she wrote (60). The same claim is heard in the interviews of historical revisionists featured in the movie Shusenjo: The Main Battleground of the Comfort Women Issue (2019), directed by Miki Dezaki.

On the back of the English booklets published by the association, 真実の歴史を追求する軍艦島島民の会 is translated as the former. In the article on Matsumoto Sakae’s testimony, it is translated as the latter.

This figure is referenced in the articles on Hankook Ilbo, JoongAng Ilbo, and in the video famously played on a billboard in Times Square, New York City in July 2017 as an initiative of Seo Kyoung-duk, a professor at Sungshin Women’s University who also appears in this clip (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCH6VdyuxGU&list=PL1sIgKU1FHchvm0lgHMN5Rp_D_3m5psN4&index=21&t=205s) of Arirang News. In the billboard video, the number of victims mentioned is 120. Hankook Ilbo and JoongAng Ilbo cited the Foundation for Supporting Victims of Forced Mobilization by Japan as the data source.

His story is recounted in the article by JoongAng Ilbo and published on August 10, 2017. At the time of his interview Lee In-woo was 92 years old, meaning he was born between 1926 and 1927, since the number 92 follows the Korean age system.

These publications are available here: http://www.japansmeijiindustrialrevolution.com/conservation/interpretation.html. The first publication on this website is an “interpretation manual” for the general guidebook Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.

The increasing censorship in Japanese textbooks is the focus of the documentary 『教育と愛国』 Education and Patriotism, produced by Mainichi Broadcasting System, first aired in 2017 and then made into a movie in 2022. The director Saika Hisayo shines a light on the tight relationship between education and politics in Japan, the increasing scrutiny of textbooks by the ruling LDP, and the self-censorship imposed on writers and publishing companies as a result. This issue had already been discussed in previous works, including Nozaki Yoshiko’s Textbook Controversy and the Production of Public Truth: Japanese Education, Nationalism, and Saburo Ienaga’s Court Challenges, 2000.

These booklets do not appear in the Industrial Heritage Information Center’s website, and are not part of the extra publications available at the link mentioned above. The booklets also don’t appear in the NCIH old website’s publication page, nor in the new website where publications are not listed (as of July 6, 2023).

On the back of the booklets in English, it is written National Consortium of Industrial Heritage (NCIH), but on their website it says National Congress of Industrial Heritage. In Japanese is the same 産業遺産国民会議; the word 会議 is usually translated as “conference, assembly, council, convention, congress…”