Abstract

The Japanese government’s refusal to recognize the presence of Korean and Chinese forced laborers during World War II at Nagasaki’s Hashima Island coal mine, popularly known as Gunkanjima (“Battleship Island”) continues since the abandoned mine was World Heritage inscribed in 2015. Hashima is one of a number of locations approved under the title “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.” Hashima has become a major tourist draw, but lacks any meaningful historical information at or near the site, while excluding any mention of Korean and Chinese forced laborers. The site also is in serious decay and appears to lack any conservation plan in line with World Heritage “Operational Guidelines.” The South Korean and Japanese governments agreed to acknowledge the presence of Koreans who “were forced to work” at the mine, but the Japanese government has subsequently refused to implement the agreement. Use of Hashima as an “urban ruins tourist attraction” instead raises questions as to whether the Japanese government has complied with requirements for World Heritage listing. This policy of neglect continues the Abe government’s refusal to acknowledge full responsibility for Japan’s injustice toward Korean forced laborers during World War II.

Keywords

Gunkanjima, World Heritage site, coal, Meiji industrialization, Korean and Chinese forced labor

Two years have gone by since the Hashima Island’s abandoned coal mine was inscribed by UNESCO as a World Heritage site. Popularly known as Gunkanjima (“Battleship Island”), the site located 19 kilometres southwest of Nagasaki harbor has been visited by over half a million people since the July 2015 World Heritage approval. The question needs to be raised: does Hashima / “Gunkanjima” World Heritage site accurately reflect the mining island’s history, a place where Japanese workers and their families lived in a Mitsubishi company town, but also where Korean and Chinese forced laborers were used during World War II? Or has this site become not much more than an urban ruins tourist attraction and a profitable operation for local Nagasaki tour boat operators, promoted and overseen by the Japanese national government as part of its “neo-nationalist policy to suppress the forced labor story”?

Nagasaki’s Gunkanjima tourist boom – cashing in on haikyo (ruins) popular culture?

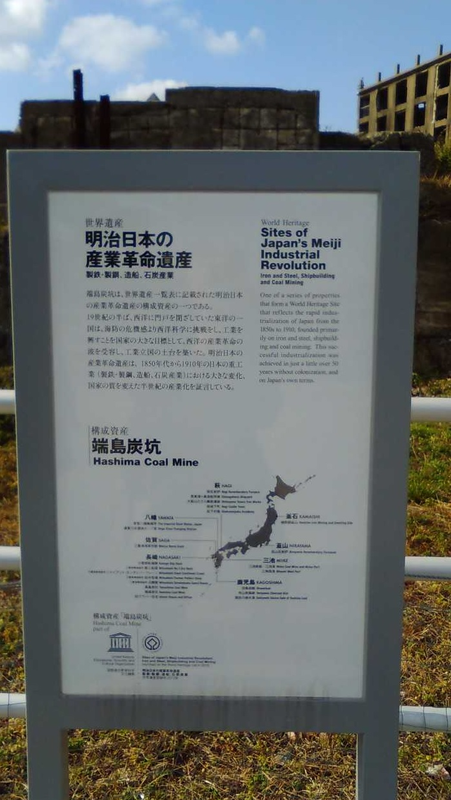

Hashima was one of 11 sites, with 23 components in “8 discrete areas” that constituted Japan’s “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” submission. These are sites where Japan’s modern iron and steel shipbuilding, mechanized coal mining, and modern iron and steel production originated. The sites also include company and government buildings related to these industries. Tourism in Nagasaki has long been a major part of the city’s economy. Hundreds of thousands of tourists visit the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and Peace Park each year, as well as over a million to the Glover House and surrounding buildings and gardens of the former foreign settlement district. The Gunkanjima boat tours now compete with these other attractions, having gone from less than 60,000 annual visitors in 2009 to over 300,000 by 2015.1 (See Table 1: Tourist visits – Nagasaki sites)

Table 1: Tourist visits – Nagasaki sites2

|

Heisei |

Year |

Gunkanjima* |

N. A Bomb Mus. |

Glover House |

Dejima |

|

21 |

2009 |

55,289 / 58,752 |

674,616 |

||

|

22 |

2010 |

84,970 / 87,626 |

658,647 |

||

|

23 |

2011 |

95,939 / 98,984 |

654,503 |

960,204 |

401,614 |

|

24 |

2012 |

103,024 / 105,981 |

644,850 |

963,362 |

410,302 |

|

25 |

2013 |

167,342 / 175,808 |

667,379 |

1,022,935 |

438,634 |

|

26 |

2014 |

191,881 / 212,833 |

671,921 |

1,035,796 |

434,910 |

|

27 |

2015 |

286,936 / 316,325 |

743,745 |

1,221,243 |

446,134 |

|

28 |

2016 |

235,658 / 259,547 ** |

* First figure is for number of tourists who landed on the island; second figure is that number in addition to tourists who toured around the island by boat but did not land on the land. ** 11 months only. If final month of previous year (2015) is added (31,096 – landing only; 34,957 – landing only plus boat tour only) the figures would be: 266,754 / 294,504. Lower figures for 2016 were due to typhoons.

Nagasaki city’s local government has been involved in promoting tourism to Hashima and collecting statistics on the number of visitors. The city has a World Heritage Promotion Office, with one section based in the city government planning office and another section mainly for promoting the existing sites and developing plans for future nominations. Statistics on tourists visiting Hashima have been kept from 2009 to 2017. Between April 2009 – March 2010 and April 2015 – March 2016, just six years, tourist numbers grew by around 500%. Over seven years – from April 2009 to February 2017 1,221,039 tourists visited the island, which totals 1,315,856 when boat tours without landings are added. The increase each year over this time span has been incremental overall, but jumped dramatically by some 100,000 in the year after the World Heritage listing.

The World Heritage listing of Gunkanjima has clearly contributed to the tourist boom for Nagasaki City. Prior to the listing, most tourists to Nagasaki were Japanese, with some Koreans and Chinese, and their destinations were primarily the Glover House and gardens complex. British entrepreneur Thomas Glover brought British and Scottish engineering, shipbuilding, and mining technology to Japan, assisting the Bakumatsu government under the Tokugawa Shogunate initially, then providing weapons to the Satsuma and Choshu clans that rebelled against the regime, and eventually working with Iwasaki Yatarō, the founder of Mitsubishi, in expanding the Nagasaki Shipyard and the Takashima and Hashima cole mines. The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum has had more than half the tourist numbers of Glover House, while tourist attendance has remained relatively stable at over 400,000 at the Dejima island museum, a reconstruction of the Dutch trading post from the Edo Era of the Tokugawa Shogunate and now surrounded by city development. Many Western tourists considered Nagasaki too distant for a one or two week whirlwind visit to Japan, opting for Hiroshima as the site for understanding the atomic bombings rather than Nagasaki. (See Table 2: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum attendance) The standard tour for Westerners has generally included the Tokyo region, Kyoto and Osaka, Himeji Castle, Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Dome and Peace Park, and perhaps Matsuyama on Shikoku or Shirakawa-go in Gifu. That pattern began to change when Gunkanjima became a unique draw for Nagasaki, though the vast majority of tourists are Japanese, along with Chinese and Koreans. One must book a reservation months in advance to get a seat on a ferry to the island, even with four tour boat companies operating twice a day, seven days a week from Nagasaki Harbor.3

Table 2: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum attendance4

|

YEAR |

TOTAL ATTENDANCE |

FOREIGN ATTENDANCE |

|

2011 |

1,213,702 |

96,510 |

|

2012 |

1,280,297 |

154,340 |

|

2013 |

1,383,129 |

200,086 |

|

2014 |

1,314,091 |

234,360 |

|

2015 |

1,495,065 |

338,891 |

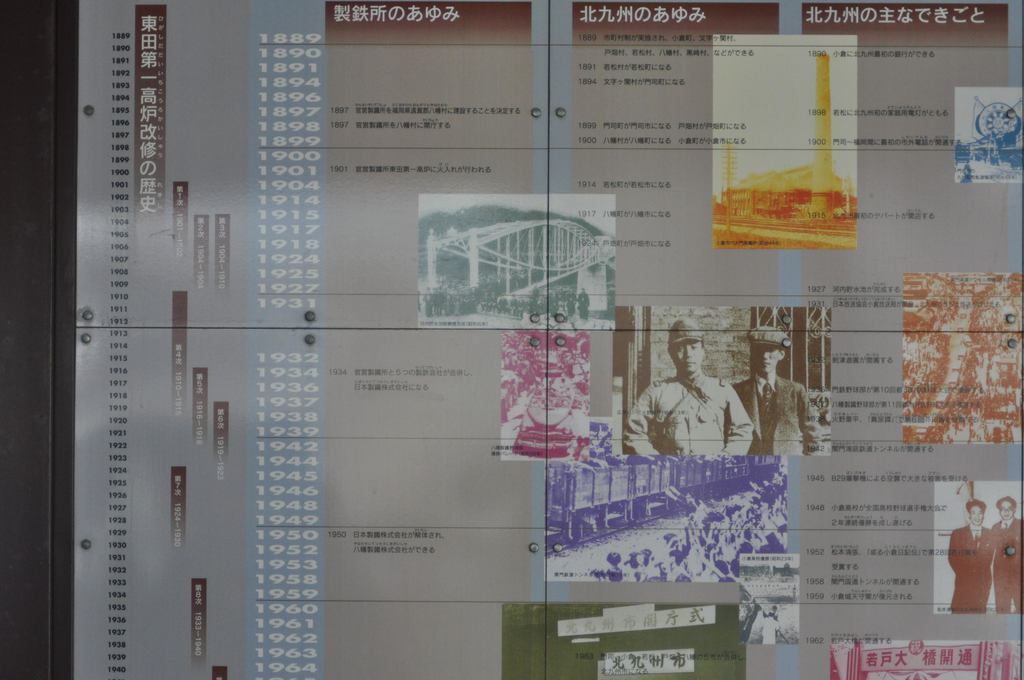

In recent years, tourism to decayed industrial and urban sites has become popular. This type of tourism is different from sites featuring restored factories and workshops that allow visitors to see antiquated technologies in operation or to enter settings where workers labored on machines during the early years of industrialization. The Lowell, Massachusetts mills and reanimated workshops in parts of England are examples of this type of sites.5 One of the “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites that approximates this approach is the original Yawata Steel Works furnace in Kokura (on Kyushu), which has extensive signage, but only in Japanese, describing the history of the works and lifelike figures of workers (who would have been from the Showa Era) by the furnace

|

Yawata Steel Works – outdoor museum figures of workers, with students |

Yawata Steel Works furnace |

Yawata Steel Works – history signage6 |

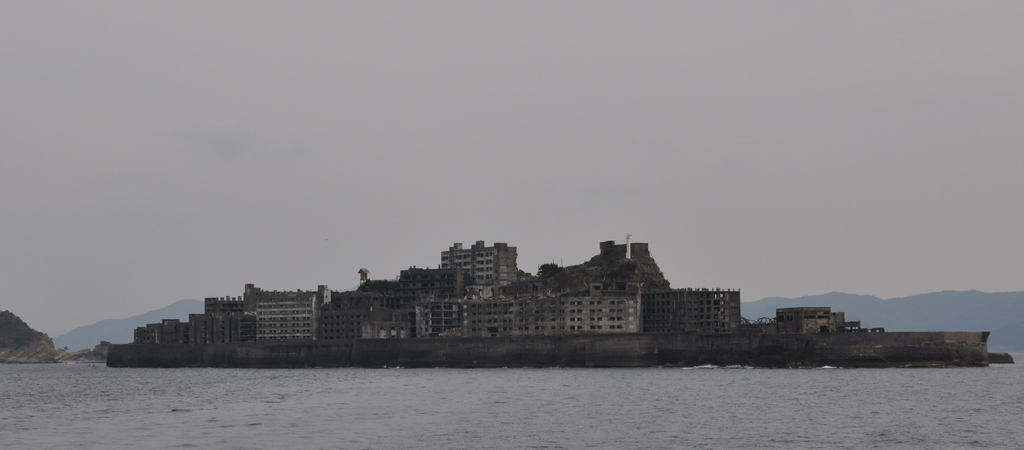

In contrast, abandoned industrial and urban sites in states of extreme decay have increasingly appealed to a public immersed in post-apocalyptic images of destroyed worlds popularized through science fiction movies, computer games, and as backdrops to rock, techno and early hip hop videos.7 Hashima appeals to this post-apocalyptical tourist urge, since nothing on the island has been restored to its original condition and there are no historical signboards describing the history of coal mining, the island “city”, the workers and people who lived there, or the Korean and Chinese forced laborers used as miners during World War II. One can buy a DVD entitled “Hashima” that has contemporary images that convey this sense of decay, an empty city cut off from civilization on an island off Nomozaki Peninsula, south of Nagasaki City. The camera scans through the ruins, overgrown with trees growing out of concrete, roofs collapsed, empty rooms with a few abandoned personal objects of the people who once inhabited this strange place, nothing but ghosts now. The photography is quite stunning in terms of color, light, and the juxtaposition of nature overtaking the ruined island buildings. The musical soundtrack ranges from vocal trance to pleasant techno, creating a mood of mystery and exploration.

What is portrayed is mainly nostalgia, an illusion of a wonderful past of a close-knit community now lost but at least not forgotten. We see photos and film clips of children playing games in the open spaces between the high rise apartments or running up and down the concrete steps; residents attending movies at the island theater; celebrations and matsuri festivals; and women doing chores such as hanging out washing. The DVD does explain the physical layout of the undersea mine and provides details on key buildings, but omits any references to Chinese or Korean miners. There is footage of Japanese miners working in the undersea tunnels and of activities in the city above the seabed, but all footage is in the post-World War II era. No buildings still standing were built during Meiji, but instead were built in Taisho and Showa eras, with specific construction dates listed in the documentary.8 The architectural information in the DVD is accurate and informative in terms of construction details, yet it fails to mention the Korean and Chinese workers’ residences or their central role as laborers. But these details also directly contradict the “Meiji Industrial Revolution” claim in the World Heritage inscription document.

A stark contrast, but one that equally elides the island’s history, to the Japanese Hashima DVD documentary is the American Hollywood James Bond blockbuster 2012 Skyfall, which uses Gunkanjima as a one minute scenic backdrop. Hashima is turned into a remote desolate island with an abandoned fictitious city that Bond and his female contact (who is also his evening bedroom companion approach, having journeyed from Macao by luxury yacht overnight. The island with its dead city turns out to be the secret hideout of villain Raoul Silva (played by Javier Bardem). Bond finally captures Raoul after a furious gun fight and arrival of MI6 helicopters, but that scene was actually shot on a different site, not on Hashima. Nevertheless, the post-apocalyptical imagery matches.9

The most recent action movie based on Hashima as “Gunkanjima” is from South Korea. Instead of the Japanese documentary depicting “empty ruins,” or an American Hollywood blockbuster that provides no contextual reference, in 2017 director Ryoo Seung-wan released The Battleship Island. In this action movie set during World War II, all the Korean forced laborers escape from Gunkanjima. The Korean miners who morph into hundreds of powerful fighters take up arms against the Japanese military controlling them, and free the Korean women forced into sexual slavery on the island, as they shoot their way to freedom and their return to Korea. Ryoo considers the movie a work of fiction based on historical facts, even though no such rebellion ever occurred on Hashima. “I even recreated the scenes from a massive escape, which is fiction, with help from experts on the history of Hashima Island and military specialists.” Ryoo has been criticized for portraying pro-Japanese Korean managers, but his outlook actually is more accurate than portraying all Koreans as anti-Japanese. “”I think in dealing with Japan’s imperial period, it’s basic to say Japan was bad … I thought, at the same time, that the film would see only half of the history if it doesn’t deal with the problem of pro-Japanese Korean managers who harshly treated their Korean colleagues. So I thought Koreans should take a cool-headed approach to ourselves, constantly criticize past historical issues and establish our own position on issues that have not been cleared up.”10 Nevertheless, the film ignores the reality that the majority of miners were Japanese and that hundreds of Chinese also worked underground as slave laborers like the Koreans. In a televised discussion, the actors talk about how they viewed the movie as “entertainment” and how they had to take on the historical physical characteristics of the Koreans who worked on Gunkanjima.

The actual history is that Mitsubishi, not hundreds of Japanese soldiers, had total control over Korean, as well as Chinese and Japanese Hashima miners, while the surrounding ocean made escape impossible and the Koreans’ isolation a certain death sentence if they physically resisted their enslavement. The Korean movie turns the entire story into an action battle between vicious Japanese soldiers and victimized but physically strong united Koreans who defeat their oppressor. The movie trailer declares “We must fight together…for life and freedom.” As the Korean fighters turn into a rebel army, Japanese bombers overhead attack them and destroy the buildings of the island. Do the Koreans get back to Korea? You’ll have to see the movie to find out.11 This is not history, even if a positive aspect to the movie is that it could increase interest in Hashima’s forced labor history.

The movie became a box office hit, with over six million viewers within twelve days of its release. It also won numerous Korean film awards. The negative is that the story is nationalist fiction, war action entertainment that is the flip side of the 2005 Japanese nationalist action movie Yamato (the largest battleship of World War II, built at the Kure Navy Yard and sister ship of the Musashi built at Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki Shipyard). Both ships had huge costs but were not used until the final years of the war, as the Imperial Navy considered they should be reserved for the “final battle” with Allied ships. By that time, US dominance of the air had destroyed much of the Japanese Navy, and both battleships had insufficient fuel to return to port in their final runs. Yamato was sunk on April 7, 1945 by US Naval aircraft off of Kyushu on its one-way voyage to Okinawa, having hardly engaged in battle.12 The difference between the two films is that the victimized Koreans unite and attack the Japanese colonial aggressors on “Battleship Island,” while the victimized Japanese are tragically defeated by the American bombers on their battleship despite their best efforts on behalf of their country.

The fictionalized popularization of Hashima as “Gunkanjima” – “Battleship Island” – that has led to distortions of the mining island’s history has affected not just Koreans and Chinese, but also Japanese miners and mining families that lived there. Sakamoto Dōtoku, who lived on Hashima with his family as a child and was a local leader in the Japanese campaign to have the island inscribed as World Heritage, objected to renaming the place “Battleship Island” when he was interviewed a year before the inscription decision. He would certainly be pleased with Japan’s success in gaining World Heritage status for the island, but one must wonder what he thinks of continued conservation neglect there. His critique, made a year before the World Heritage decision, addressed in part how this popular distortion has hurt him personally by neglecting how Japanese miners and their families actually lived during the 1950s before the site was abandoned.

“Recently, when we speak of haikyo, the name of Gunkanjima is always cited. I don’t know if there’s a haikyo boom or something, if it’s a new trend… But I don’t like that term at all. In the media, they love mentioning Gunkanjima with catchy headlines like “The Queen of Ruins”, “The Abandoned Island”, “The Tombstone”, and so on… It’s so macabre! However, for us who lived on the island and despite its dilapidated condition, … it still is… our home. Where we come from. It’s really sad to juxtapose Hashima with the word haikyo or ruin. We know it’s the reason why the island gets more and more attention but what would people think if we called their hometown a ruin? Besides, since the island is uninhabited ([since 1974]), it has been vandalized many times. Today, the island cries. It suffers and dies out, annihilated little by little by natural causes but also by people – that I can’t forgive – who keep on vandalizing it.”13

Hashima’s “Outstanding Universal Value” and post-Meiji buildings as evidence – for “all humanity” or just Japanese nationalism?

As tourists travel by boat from Nagasaki port out to Hashima, they are shown a video about the island and its official history. The brief documentary moves through early development of the mine and ends by relating stories of everyday work and life of the Japanese miners and their families during the 1960s in a way that Sakamoto would approve. But once on the island the “ruins” of Battleship Island overwhelm visitors, even with the Japanese-language guides who describe of some of the buildings’ history, such as when a structure was built and with what materials, where the residences, school, and movie theater were located, and the various industrial remains used for mining. Prior to landing, the boat circles the island and stops at a distance from which it appears to have the shape of the “battleship.”

|

Gunkanjima view from tourist ferry, appearing as a battleship |

Then the tour proceeds to the opposite side where visitors disembark at a special landing dock. What tourists then encounter along a special concrete walkway hugging the seawall is a World Heritage site in which virtually no restoration work has been done on the still standing Taisho and Showa-era buildings.

Tze M. Loo has described Hashima and other sites where Korean forced laborers worked as “Japan’s dark industrial heritage” that is hidden so that the official version “functions, in effect, as a circuit of state-sanctioned national history and cultural value.”14 Japan’s nationalist policy approach to the management of Gunkanjima neglects the most basic conservation of these buildings and runs counter to the “Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention.” The “Guidelines” requiring periodic reporting include “provid[ing] an assessment as to whether the Outstanding Universal Value of the properties inscribed on the World Heritage List is being maintained over time.” The definition of Outstanding Universal Value “means cultural and/or natural significance which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity.”15 Note the wording here: not solely for national interests (in this case Japanese national interests) but for all humanity. Failure to convey the full history of Gunkanjima by making Korean and Chinese miners vanish from the tourist narrative makes the site appear to be solely Japanese without any other nationalities present, above all eliding a central story of Japanese colonialism and the history of its Korean and Chinese forced laborers.

The company history of Hashima is well known. Mitsubishi bought the Hashima undersea coal mine from the Meiji government in 1890, having earlier purchased the neighboring Takashima undersea coal mine, two kilometers away, in 1881.16 The two adjacent island mines were managed by Mitsubishi as a single company, Takashima Coal Mining Company under the zaibatsu’s mining division. English entrepreneur Thomas Glover assisted Mitsubishi head Iwasaki Yatarō in modernizing the technology used in the mine. Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki Shipyard had an engineering works that built mining technology used at the Hashima and Takashima mines, which were Japan’s first mechanized coal mines. Mitsubishi mining machinery also was sold to the Mitsui zaibatsu for use in its Miike coal mine, one of the largest in Kyushu and one of the last Kyushu-based mines to close in the postwar period when oil replaced coal as Japan’s main fuel.

Nagasaki became a vast military-industrial complex prior to World War II. Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki Shipyard was the largest private shipbuilding facility in East Asia at that time, and the city and surrounding region had over 40 worksites run by Mitsubishi.17 The demand for labor during the war, resulting from Japanese workers being conscripted into the military, led to the government policy of “conscripting” Korean men by force to fill Japanese places in industry, construction, and general labor within Japan. Mitsubishi used 6,350 Koreans in the Nagasaki Shipyard, according to Kim Soong-il, who worked there during the war and recorded what he saw in a secret diary. He claims that 500 Koreans worked at the Hashima mine. At Hashima there also were Chinese workers, many of whom would have been prisoners-of-war captured in northeast China where Communist guerrillas resisted the Japanese occupation.18

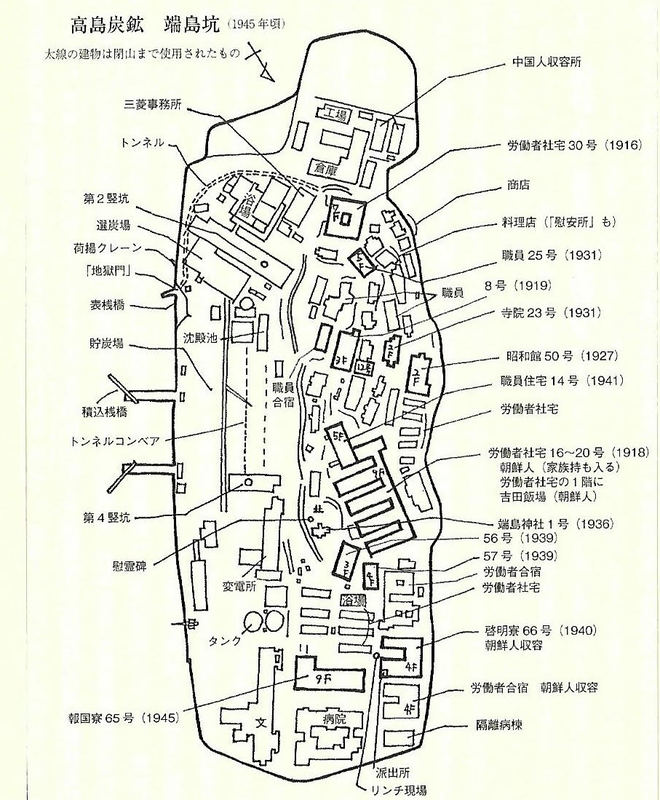

The Chinese workers had their own dormitory on Hashima in a building that was later demolished.

|

Map of World War II Hashima, from Takeuchi, Chyōsa |

Hashima – Chinese dorm location19 |

Visitors are taken to a location at the south end of the island where this empty space reveals buildings behind it, but are not informed that Chinese once lived on this spot. Koreans were housed in a dormitory in Building 66, built in 1940 and still standing, on the west side of the island. But all information states that these were Japanese family residences.

|

Hashima, building where Korean dorm was located / Building 6620 |

The irony is that all the buildings one sees when on Gunkanjima were built after the Meiji Era, and so cannot fit the official description “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.”

|

Map of Hashima with buildings, depicted in tourist pamphlet |

List of Hashima buildings, from tourist pamphlet |

Visitors are shown the location of the mine pit that became the basis for Japan claiming this was a Meiji-era industrial site, but one can hardly see where the pit is due to restrictions of access beyond the designated paths. It is true that Hashima’s coal mine was crucial to the Meiji era industrial revolution, but the remaining physical evidence of this hardly exists today. Furthermore, the innovations in advanced mining technology and reinforced concrete buildings above ground were introduced in the post-Meiji era. If one were to remove all the post-Meiji structures on the island there would be no “tourist draw” as there would be no “abandoned concrete building city” visible.21

Hashima does deserve to have World Heritage status, but only if the context of Korean and Chinese forced labor is recognized and the story of the fate of those workers is told. The description of “Meiji” industrial revolution is inaccurate because the site as it is viewed by visitors has far more structures related to industrialization in the Taisho and Showa eras. The site therefore should be accurately described simply as an important component in “Japan’s industrial revolution” spanning Meiji, Taisho and Showa eras, and it should include a full history of all the coal mining island’s workers as the basis of that industrial revolution. Furthermore, the site desperately needs to have conservation work done to preserve the buildings from further deterioration. The excuse given by the Nagasaki World Heritage Promotion Office has been that signage would disturb the site.

In response to an inquiry by my Japanese colleague, a long time Nagasaki resident, regarding the absence of historical signage, the city office had a “No Trespassing” sign installed at the dock entrance where visitors embark, but the city office also seems to have been instrumental in having a new Hashima historical information sign put up identifying Hashima Coal Mine as one of the “World Heritage Sites of Japan’s Industrial Revolution – Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding, and Coal Mining.” Nevertheless, there is no substantial historical information on Hashima, no map of the island’s building with construction dates, no mention of Mitsubishi ownership, no mention of workers used there (Japanese, along with Korean and Chinese during World War II), and no historical chronology as existed for many previous years at the Yawata Steel Works outdoor museum. The new Hashima World Heritage sign is in Japanese and English, but not in Korean or Chinese.

|

Hashima “No Trespassing” sign at tourist landing entrance22 |

|

The failure of the national government to have a systematic building conservation plan, aside from the seawall repair, indicates extreme neglect of what should be expected for World Heritage listing. The Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Dome, by contrast, is regularly repaired. In Shirakawa-go traditional thatched roofed buildings require constant upkeep and repair. Commonly known as minka, these multi-story rural dwellings and storehouses had thick roofs that could endure heavy mountain snows while keeping in warmth. They required dozens of villagers working together to maintain new thatch installation. With the advent of modern roofing, traditional thatch became far too expensive to re-install, and many minka villages were abandoned as younger people left rural mountain regions for employment in urban areas. To counter this erosion of rural village life and culture, Shirakawa-go was reconstructed and maintained with substantial government financing along with promotion of traditional skills required for installing minka thatch roofing. World Heritage inscription of the large village has contributed to tourism and financial self-sufficiency to a degree. Shirakawa-go could not survive without a carefully planned and financed conservation policy.

In contrast, Hashima is being left to rot, as if conservation of buildings would ruin the image that draws tourists to the site. This failure to conduct conservation to preserve the structures on the site ignores the “Integrity” section of the World Heritage Committee approval document, which notes: “In terms of the integrity of individual sites, though the level of intactness of the components is variable, they demonstrate the necessary attributes to convey Outstanding Universal Value. The archaeological evidence appears to be extensive and merits detail recording research and vigilant protection…A few of the attributes are vulnerable or highly vulnerable in terms of their state of conservation. The Hashima Coal Mine is in a state of deterioration and presents substantial conservation challenges.”23 Two years after the Committee’s document was published there appears to be almost no conservation of the main structures on the island or concern for hundreds of objects inside the structures that are rapidly deteriorating from open exposure to severe weather and the sea, nor is there any clear identification of buildings still standing.

Reporting maintenance and progress of World Heritage status: Has the Japanese government carried out the UNESCO recommendations for Hashima?

An accurate depiction of Hashima’s history would not only benefit the hundreds of thousands of tourists visiting the island, but also could potentially contribute to improving strained relations between Japan and Korea (South and North), by acknowledging both the injustice done to Koreans in the past and the accomplishments of all miners – Japanese, Korean, and Chinese – who were the basis of Japan’s industrialization. Nevertheless, this industrialization led to use of forced labor during the era of the Pacific War, without reparations for surviving workers or the families of deceased workers. In South Korea there are ongoing litigations for reparations and unpaid wages that the Japanese government and companies like Mitsubishi refuse to recognize as legitimate. What tourists see on Hashima is not “Meiji Era Industrialization” – it is Taisho and Showa Era industrialization that was post-Meiji, but which began on an island that Meiji era people would not recognize today.

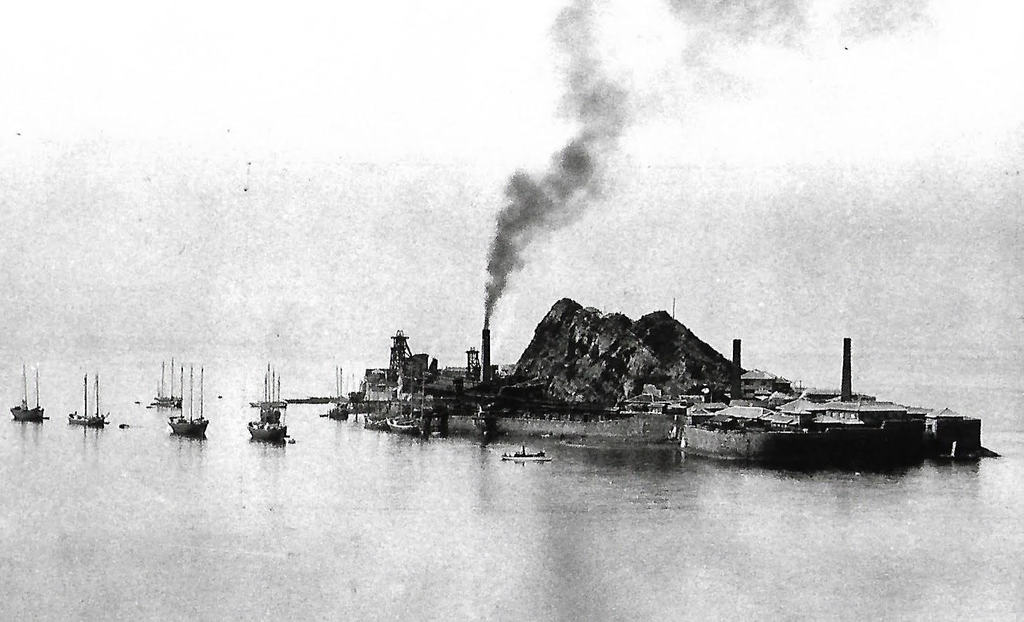

|

Hashima in Meiji – 191024 |

In its 2015 decision, the World Heritage Committee listed eight recommendations “for consideration.” The first six points focused on conservation, maintenance, and management of the sites, while Point 8 dealt in part with the problems of road construction projects at Shuseikan (spinning mill buildings, foundations in Kagoshima prefecture) and Mietsu Naval Dock (remains of wooden dry dock in Saga prefecture), and a new anchorage facility at Miike Port (historic features, port still operational, in Kumamoto prefecture).25 More generally, however, point 8, specifies that this recommendation involves “submitting … proposals for the upgrade or development of visitor facilities to the World Heritage Commission for examination, in accordance with paragraph 172 of the Operational Guidelines,” which can be interpreted as applying to all sites in the inscription, including Hashima.

Point 7 of the recommendations has particular relevance to Hashima, and it is on this point that there is substantial evidence that the Japanese government has failed to comply with the World Heritage Committee’s original recommendations, although wording preceding the recommendation list does qualify with the terminology “give consideration to the following.” This phrasing raises the problem of enforcement of World Heritage inscription “recommendations.” Are these merely voluntary, or can serious failure to follow through with recommendations lead to withdrawal of inscription? Like so many aspects of United Nations policies, enforcement inevitably conflicts with national states’ interests and claims to sovereignty. Historically such UN enforcement problems have been highly political, and World Heritage inscription has been no exception. The text of Point 7 states:

“Preparing an interpretive strategy for the presentation of the property, which gives particular emphasis to the way each of the sites contributes to Outstanding Universal Value and reflects one or more of the phases of industrialization; and also allows an understanding of the full history of each site.”

The Japanese government is required to “submit a report outlining progress with [eight recommendations on the sites’ conservation, management, and presentation of the history] to the World Heritage Centre, by 1 December 2017, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 42nd session in 2018.”26 The report applies to all the “Meiji Industrial Revolution” inscriptions. Hashima is by far the most popular tourist destination of the 11 sites and has received the most international publicity. Over the last two years has the Japanese government fulfilled these recommendations for Hashima?

The “Protection and Management Responsibilities” section of the World Heritage Committee decision recognizes that Japan already had existing laws related to cultural and landscape conservation, which were viewed as advantageous for proper operation and preservation of these sites. Most important are the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties and the “Landscape Act that applies to the privately owned and still operational sites that are protected as Structures of Landscape Importance.” Hashima and Takashima were previously owned by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and used for coal mining, but after Hashima was closed in 1974 the corporation cleared the island of all people, while the Takashima coal mine was closed in 1986 but people continued living on the island. Mitsubishi transferred Hashima to the town of Takashima in 2002. In 2005, Nagasaki city merged Takashima and a number of other municipalities into the city’s jurisdiction, making Hashima part of Nagasaki city. The role of Nagasaki’s city government therefore is crucial in how the current World Heritage site is managed, in conjunction with the national government of Japan.

The Abe government developed a framework for administering the sites that has actually marginalized the role of local government in Nagasaki and in essence excluded local non-government groups, as well as concerned local residents, from participation in decisions. This Japanese national government “framework” is outlined in the World Heritage Committee decision:

“The Japanese Government has established a new partnership-based framework for the conservation and management of the property and its components including the operational sites. This is known as the General Principles and Strategic Framework for the Conservation and Management of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Kyushu-Yamaguchi and Related Areas. Japan’s Cabinet Secretariat has the overall responsibility for the implementation of the framework. Under this strategic framework a wide range of stakeholders, including relevant national and local government agencies and private companies, will develop a close partnership to protect and manage the property. In addition to these mechanisms, the private companies Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd., Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation and Miike Port Logistics Corporation have entered into agreements with the Cabinet Secretariat to protect, conserve and manage their relevant components.”

The “wide range of stakeholders,” beyond national government agencies, local government, and private companies, unfortunately is not specified in this document. Nevertheless, the World Heritage Committee seems to have anticipated potential problems with this vague description and expressed concern that this be addressed:

“Attention should be given to monitoring the effectiveness of the new partnership-based framework, and to putting in place an on-going capacity building programme for staff. There is also a need to ensure that appropriate heritage advice is routinely available for privately owned sites. What is urgently needed is an interpretation strategy to show how each site or component relates to the overall series, particularly in terms of the way they reflect the one or more phases of Japan’s industrialisation and convey their contribution to Outstanding Universal Value.”

Hashima’s “staff” in fact consists exclusively of the private tour guides connected to the private tour boats. There appears to be no “heritage advice” that has been taken seriously by those in charge of the Hashima site. If staffing arrangement exists, it is not evident at the site or in the tours. Does the management oversight in practice depend on the Nagasaki World Heritage Promotion Office or the Abe government’s Cabinet Secretariat? Prime Minister Abe’s public statements refusing to acknowledge that Koreans “were forced to work” (hatarakasareta) at Hashima during World War II has negated the original compromise between Japan and South Korea which paved the way for approval of the Japanese UNESCO site. His statements indicate that the national government controls overall policy on how history is presented, while local government has been relegated to tourist promotion. Prime Minister Abe has rejected, in practice, the original call for an “urgently needed…interpretation strategy [that] reflect[s]…and convey[s]… Outstanding Universal Value” for the Hashima site. At present there appears to be no strategy for Hashima aside from tourism and maintaining the seawall, although a plan for a Tokyo-based World Heritage museum covering all “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites has surfaced in the media.

Japan’s other World Heritage sites: proof of Hashima’s neglect?

The failure of the Japanese government to present Hashima’s history is all too evident when comparing two other major World Heritage Sites in Japan that receive hundreds of thousands of visitors each year: the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Dome (with adjacent Peace Park and Peace Museum complementing the World Heritage listed Dome); and Shirakawa-go in the mountains of Gifu Prefecture where an entire village has been preserved and maintained with traditional houses in the gassho style (these include houses with high, thatched roofs and large timber beams).27 Both sites have extensive historical signage. Both have extensive historical descriptions – in Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean – of objects and structures that define the history of these sites.

At Shirakawa-go, all buildings and locations are clearly identified with this signage.

|

Shirakawa-go, overlooking view from mountain |

Shirakawa-go, restored mill |

Shirakawa-go, inside a restored minka house28 |

One can get a full sense of the history – cultural, social, political and economic – from the descriptions. The buildings (many still occupied, others entirely historical preservations) are superbly maintained and accessible. In the case of the Hiroshima Peace Park there are many memorial sites with clear descriptions, including one devoted to Koreans who died in the atomic bombing. At Shirakawa-go, one can walk through an entire section of the site recreated in its original form, with dwellings, store houses, a mill for grinding grain, and even a tea house. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum is professionally run with detailed descriptions of the city before the bombing, the consequence of the bombing, and how the city rebuilt later. The Museum employs a director who is academically trained, and has a well maintained and staffed archive with hundreds of thousands of “testimony” recordings of hibakusha survivors. Memorial plaques throughout the park provide information on those who perished or survived the atomic bombing, but also their place within Japanese society, including a monument to Korean hibakusha.

The presentation of the full history at both these World Heritage Sites – Hiroshima and Shirakawa-go – is not only evident but has improved over the years. In contrast, the Hashima site has no historical identification on the island. The only “understanding” one gets when taking a private tour boat to the site is the brief documentary video shown in Japanese (with English headphones available) that presents the island’s history as a place where there was a vibrant Japanese community of miners and their families, cheerfully enjoying the densely packed island town while the Japanese miners laboring underground worked hard to earn their living, taking pride in their jobs. If there were ever any labor disputes, one does not learn this from the video, nor do we learn anything about the trade unions that miners might have been affiliated with or what happened to those unions during the fierce anti-union company campaigns of the 1950s. Mitsubishi as owner of the mine is visible but more as a backdrop to the story. Missing is any discussion of World War II and the company’s responsibility toward the thousands workers including Chinese and Korean forced laborers, as well as Japanese labor. World War II and the Nagasaki atomic bombing are not part of the story told to tourists on the boat.

When picking up one’s ticket prior to boarding a boat to the island, pamphlets on Hashima’s history are available, including ones in English, Korean, and Chinese as well as Japanes. These are apparently published by Nagasaki’s Tourist Office, but no other identifier is on the publication. The pamphlet lists entry costs (tourist boat costs are separate and not listed); a chronological history of Gunkanjima; a map of the island and its buildings; a list of buildings with their names and dates constructed; a safety protocol list for visitors; photos of buildings and historical photos of workers; and diagrams and an explanation of undersea mining. No mention is made of early convict labor, or later Korean and Chinese forced labor, which is consistent with the current Abe government national policy position. All buildings listed date from 1916 or later – none within Meiji – but brief historical descriptions describe Meiji era buildings that no longer exist. Some of the main seawalls were constructed during Meiji as the island was expanded through landfill. Coal pits were dug during Meiji, but the location of the pits and details on when they were constructed are not mentioned in the pamphlet, nor can one view the Meiji-era pits on the brief walking tour that is restricted to the south seawall end of the island, away from the main buildings.29 A photo of Hashima taken as late as 1910, two years before the end of the Meiji Era (1912), shows an island completely different than a decade later when high rise apartments gave it the “battleship” image recognized by the public today.30

When I toured the site with a Japanese colleague in March 2017, he approached some Chinese visitors and asked them if they knew that Chinese once worked in the mines there. They were surprised, saying they had no idea. This was at the end of the guided tour done entirely in Japanese, although an audio guide in other languages was available, with commentary far briefer than the live Japanese tour guide talk. The main part of the tour actually looked over an empty concreted area where the Chinese dormitories once stood.

There is a privately run “Gunkanjima Digital Museum” at Nagasaki port across from the Nagasaki International Cruise Ship Terminal. The information at the museum is similar to the pamphlet issued to tour boat visitors to the island, but photos (at least on the website “Gallery”) are all from the 1950s through the closure. The website has no in depth history and appears designed simply to draw tourists to the ruins of the island. All “news” and “staff blogs” are in Japanese, no other languages. There is no mention of convict labor, Koreans, or Japanese on the website. Nor is there mention of forced Korean or Chinese labor. Viewing this site, one would never know that Nagasaki endured World War II or was destroyed by an atomic bomb. There is no reference to the other World Heritage sites in the “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” inscription. But one can get full tour boat information on this website courtesy of the Gunkanjima Concierge Company.31

Nagasaki’s wartime industry and labor history – local involvement versus national policy control

A major problem in terms of implementing a meaningful presentation of the full history of Hashima, as required under the World Heritage category of “Universal Values,” has been the usurpation of local involvement and local government in managing and improving the Hashima site. In 2015 there was a debate in Nagasaki over which local sites would be best to nominate for World Heritage listing. Many in Nagasaki wanted the Christian heritage of Nagasaki and Kumamoto to be World Heritage listed. This inscription would have included the hidden Christian locations on Nagasaki’s coast, islands, and historic sites of the Christian rebellion on the Shimabara Peninsula, all during the violent Tokugawa Shogunate religious prohibition, as well as Christian churches from the Meiji Restoration when Christianity was again made legal and that commemorated the Christian martyrs during the era of persecution.32 The Abe government rejected this approach in 2015 and instead prioritized sites of Japan’s industrial revolution just before and during the Meiji Era for World Heritage nomination. To achieve this shift in nominations, the Abe government changed the executive powers to recommend World Heritage nominations from the Ministry of Culture, which would have had to consider local government recommendations, to the Cabinet under Prime Minister Abe’s direction. A special section under the Ministers’ Secretariats was established, and Abe appointed his childhood friend Kato Koko to head the section. The industrial revolution sites recommendation was based in part on the Abe government’s policy of revitalizing the economies of local communities under the guidance of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. National governments of states are the nominating party for World Heritage candidates, but the issue of consultation should be part of the nomination process. In the case of nominating Christian heritage sites, local interests were overruled for national government priorities.

Nagasaki City stood to benefit from a successful decision on the industrial revolution sites in terms of enhanced tourism, but other sites in more remote regions that were inscribed in the final World Heritage Committee decision, such as the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine site, have failed to attract substantial numbers of tourists. Mitsui’s Miike Coal Mine site in Omuta has particular importance for Japan’s industrial and social history. According to Miyamoto Takashi, “[r]egistration of the coal mine … was expected to boost tourism industry in the region. However, its effect has not been deeply felt by the local population thus far.” Miyamoto views this as a loss of memory of industrialisation, which will also lead to a loss of memory of those who worked there, including convicts used as miners in the first decades when the mine opened. Furthermore, Allied POWs, Koreans, and Chinese worked as forced labor in the Miike Mine in World War II. Certainly this mine represents more than Japan’s “achievement” of industrialization. But the low number of tourists visiting the site led Omuta City to cancel round-trip bus services to the site.33 The core issue, however, should not be tourism but the “Outstanding Universal Value” of sites and how these sites are presented to the public, with historical accuracy and engagement, not just their entertainment attraction. Miyamoto’s critique applies equally to Hashima and to what can only be described as the Japanese national government’s promotion of “loss of memory” there.

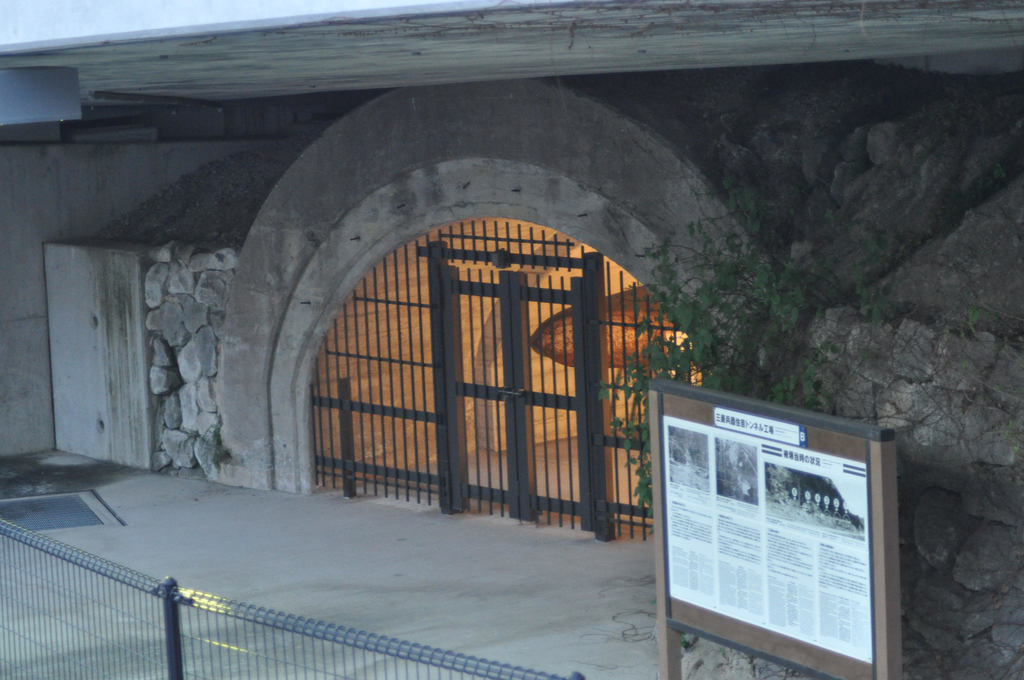

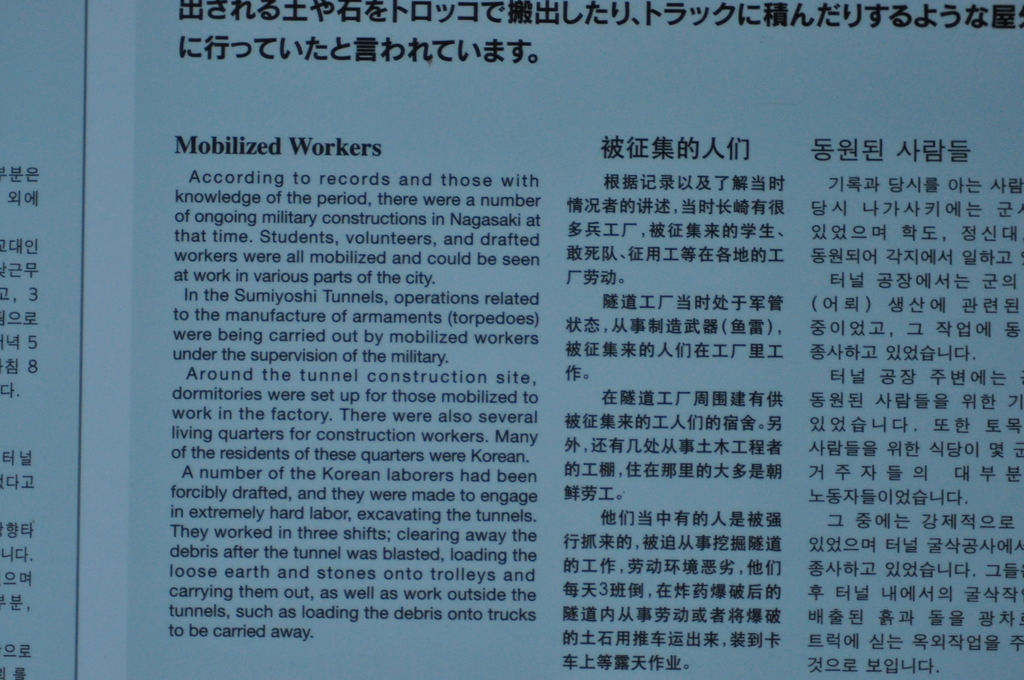

In contrast to Japan’s national government, local governments have made an effort to contextualize industrial history in their region, even if some of the history presented neglects to mention Korean and Chinese forced laborers or Allied POWs who worked in the mines in wartime.34 Nagasaki City has a remarkable site that few tourists visit, one that has far more historical information than one finds at the Hashima site. During World War II, the military had many underground tunnels and factories built throughout Japan as a way to avoid destruction by US bombing raids. Nagasaki City was riddled with these underground facilities, dug out of solid rock by Korean forced laborers. Construction was overseen by the military, while supervised and managed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries that ran the production. Local Japanese and Korean-Japanese activists in Nagasaki helped persuade the local government to restore several of the entrances to an underground facility at Mitsubishi’s Sumiyoshi site, which had been sealed previously to prevent access. The site is within city limits, adjacent to a parking lot, and set among local houses and stores. The entrance and immediate inner area have been fully restored to original condition, and the interior includes displays of torpedoes that were manufactured during the war.

|

Nagasaki City, Sumiyoshi tunnel with torpedo |

Nagasaki City, Sumiyoshi tunnels and parking lot in forefront |

Nagasaki City, Sumiyoshi tunnels historical plaque describing “Korean laborers… forcibly drafted”35 |

The entrances have bars, but these are designed to allow views inside that light up by sensors when approached. Sturdy display plaques in Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean that are outside the tunnel entrances describe the history of the industrial site in detail, including descriptions of workers who were present and photos taken when the site was operational. A major problem with this site, however, is that it is hidden from view and dominated by the parking lot, as well as its distance from the main tourist sites in the Urakami District, such as the Atomic Bomb Museum and Urakami Cathedral. The site could be improved if the city purchased the parking lot and turned it into a park. This site could then be promoted as part of a larger historical tour of wartime Nagasaki that would encompass many sites, particularly Hashima and the Nagasaki Peace Park, Memorial Hall, and Museum.

The Sumiyoshi World War II tunnel restoration, even with its limitations, could serve as a model for presentation of Gunkanjima’s history. The language used on the outdoor plaques explaining the conditions faced by Koreans is similar to that used in the final World Heritage site understanding agreed to by the Korean and Japanese representatives in 2015, but absent from the Hashima site, tourist pamphlet, port ticketing areas, and the privately owned “Gunkanjima Digital Museum.” Here is the Mitsubishi Sumiyoshi tunnel description in English (also displayed in Japanese, Korean, and Chinese, with content the same in each language):

Mobilized Workers … Students, volunteers, and drafted workers were all mobilized and could be seen at work in various parts of the city. In the Sumiyoshi tunnels, operations related to the manufacture of armaments (torpedoes) were being carried out by mobilized workers under the supervision of the military. Around the tunnel construction site, dormitories were set up for those mobilized to work in the factory. There were also several quarters for construction workers. Many of the residents of these quarters were Korean. A number of the Koreans had been forcibly drafted, and they were made to engage in extremely hard labor, excavating the tunnels. They worked in three shifts; clearing away the debris after the tunnel was blasted, loading the loose earth and stones onto trolleys, as well as work outside the tunnels, such as loading the debris onto trucks to be carried away.36

The Sumiyoshi site restoration also contrasts with the deplorable condition of Hashima’s structures, which are rapidly decaying and desperately require conservation work rather than just keeping the buildings as an abstract ruined city of unnamed ghosts. Hashima’s current condition overall runs counter to the spirit of the values and requirements of World Heritage sites. But a model for changing this already exists in Nagasaki. The local government has shown a far more progressive policy in this area than Abe’s national government. The World Heritage Committee needs to raise this issue if Hashima is to exist as more than a rotting, island urban wasteland in future decades.

The 2015 South Korea / Japan compromise on Korean workers at Hashima – What is needed for genuine implementation

The original South Korean objection to Hashima being inscribed as a World Heritage site because of the presence of Korean forced laborers during World War II was resolved through a compromise in July 2015. This compromise was a side agreement, and is not mentioned in the final document issued by the World Heritage Committee. Unfortunately Japan has failed to fulfill its promise to implement the agreement. The wording stated that Koreans “were forced to work” (hatarakasareta) instead of the term “forced labor” (kyōsei renkō) that has been used in South Korean litigations against Japanese corporations for wartime practices, and which also is standard phrasing in all Zainichi histories on Korean workers in Japan during wartime that have been published in Japanese. This compromise appeared to go further than “conscripted labor” (chyōdō rōdō) used by the Japanese government and companies that have been defendants in litigations, and a term that was standard in all Japanese wartime documents related to Korean labor taken to Japan. In 2015, Professor Kimura Kan of Kobe University responded prophetically to this “compromise” by stating that it was just “a play on words,” while the Japanese representative on the World Heritage Committee, Sato Kuni, admitted that some Koreans “were brought against their will and forced to work under severe conditions” at some industrial sites.37 We now know that the previous South Korean government of President Park, long since discredited for corruption, agreed to the “compromise” so that Japan would support South Korea’s own World Heritage nominations that same year.38

Most egregious is the Japanese government’s current policy to go further by apparently claiming that Koreans at Hashima did not work under duress, but had the same conditions as Japanese workers. As of December 2017, it was revealed that the Abe government even had conducted “200 hours of video recordings of around 60 former islanders, including Korean residents in Japan” who claimed that Koreans were treated no differently than Japanese miners.39 To have validity, those interviewed would have to be at least 90 years old to have worked underground with Koreans or as Korean laborers.40 Unless those interviewed were actual miners, working underground, their testimony would be regarded as hearsay in a court of law, as they were not in the mine at the time. Finally, there was a hierarchy of Koreans in all forced labor situations in Japan, with a very few acting as supervisors for Japanese managers while the majority of Koreans had no such privilege. This “testimony” also could easily be challenged by the many accounts of Koreans who did suffer as forced laborers in many locations throughout Japan, particularly in the coal mines.

The Abe government’s failure to address the absence of any proper historical information in Nagasaki on Hashima will be made worse if the plan to have World Heritage sites museum in Tokyo focused on Japan’s industrial revolution is implemented instead of locating the museum in Nagasaki City.41 Overall, these new policies and actions by the Abe government can be viewed as a reaction to the election of Jae-in Moon to the South Korean Presidency. President Moon has made it clear that he supports full recognition and redress for the injustices done to Korean forced laborers and Korean women forced into sexual slavery (“comfort women”) by the Japanese military in World War II. In August 2017 President Moon stated that the postwar treaty that normalized diplomatic ties with Japan and that waived further reparations to South Korea for wartime related issues should not infringe on the rights of individual Koreans who continue to seek unpaid wages and compensation for forced labor during Japan’s colonial rule from 1910 to 1945. He reaffirmed his support for the South Korean Supreme Court’s judgment on the issue, in contrast to President Park, who remained silent on the Court’s decision.42 President Moon has also called for a national commemoration day for former forced laborers and sex slaves, along with memorial statues to remember their history. The Abe government has vehemently opposed these positions.

Many people have yet to also understand that the Korean forced labor and Korean “comfort women” historical controversies are linked, and that link relates to the injustice against Koreans currently hidden from view to those visiting Gunkanjima. In the late 1930s, Mitsubishi and other Japanese companies with coal mines introduced the use of Korean women as sex slaves to “motivate” Korean workers who were brought to Japan to be more “productive.” These Korean women were meant to mainly service Korean workers, as the Korean men had no families present and could not leave the island. The deceptive recruitment of young Korean women for this purpose occurred throughout the mining regions of Japan, including at Mitsubishi’s Hashima and Takashima Island undersea coal mines near Nagasaki city. According to historian Takeuchi Yasuto:

Mitsubishi everywhere encouraged the opening of shops with women in them and also promoted gambling … Around 1907 at Hashima there was a shop with women … [By the 1930s] on Takashima at Ohama and Honmachi there were a number of shops, and in the Honmachi shop there were only Korean women. In June 1937 at Hashima, a Korean woman who was a ‘barmaid’ committed suicide by drinking creosol. Honda Iseimatsu [who] reported it … was the manager of the Honda Shop. The exploited woman who was a young person of 18 had no choice but to kill herself … An article entitled “Special Comfort Women Stations” in “Labor and Management of Koreans at the Coal Mines” [published by] the Coal Mining Control Association [circa 1939], Kyushu Branch advised that it is good to have a limit of ten women for every 1,000 Korean workers … [T]he coal mine labor section [of Sanpō, the government’s fascist labor union] held a meeting of managers and women employees on “Women’s Duty to Prevent Escaping and to Encourage Increased Production.” At Mitsubishi Takashima [Hashima and Takashima island mines], it was apparent that the police and managers collaborated in controlling sexual slavery of the women. By the period of 1939, sexual slavery at Takashima and Hashima seems to have reached a total of 80 women, and in response there appears to have been opposition [to the forced prostitution] from the coal mining workers.43

The May 2017 change in government in South Korea under President Moon led to a renewed effort to gain acknowledgment and compensation for Korean women who were forced into sexual slavery and Korean men used as forced laborers by Japan during World War II. President Moon’s attention to these outstanding historical grievances indicates South Korea’s new democratic trend, which includes responding to popular grievances, as well as advocating transparency in government and honesty inn diplomacy, something lacking in Japan under Prime Minister Abe’s policies regarding World War II history and how it continues to influence international politics in East Asia. President Moon’s renewed focus on the forced labor and sexual slavery issue has taken a new, constructive approach but one that has retained a forthright attitude while not lapsing into angry nationalism. He addressed Prime Minister Abe by stating that “[i]t is necessary for Japanese leaders to take a courageous attitude” in resolving the issues of forced labor and “comfort women.”

It would be advantageous for the Abe government to reverse the current policy of denying the history of abuses Koreans suffered in Japan during World War II in the first instance by acknowledging the well-documented historical facts of life and work at the Mitsubishi Hashima Coal Mine at that time. But the Abe government’s latest move to actively deny the history of Korean mistreatment at Hashima; its failure to properly conduct conservation of structures rapidly deteriorating on the island; and its plans to promote a nationalist history of Hashima in Tokyo while not building a site in Nagasaki City, a location near the majority of “Meiji Industrial Revolution” sites indicates that requirements outlined in the 2015 UNESCO World Heritage Committee decision have not been met. We can only hope that the World Heritage Committee will criticize this failure and recommend a range of corrections required for Hashima to retain World Heritage status.

Related articles

- Byung-Ho Chung, “Coming Home After 70 Years: Repatriation of Korean Forced Laborers from Japan and Reconciliation in East Asia,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 12, no. 1, June 9, 2017

- Tze M. Loo, “Japan’s Dark Industrial Heritage: An Introduction,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 1, no. 1, Jan. 1, 2017

- Miyamoto Takashi, “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 1, no. 31, Jan. 1, 2017.

- Takazane Yasunori, “Should “Gunkanjima Be a World Heritage Site? The forgotten scars of Korean Forced Labor,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 13, issue 28, No. 1, July 13, 2015

- William Underwood and Mark Siemons, “Island of Horror: Gunkanjima and Japan’s Quest for UNESCO World Heritage Status,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 13, Issue 26, No. 3, June 29, 2015

- Seung-ho Lee, “A New Paradigm for Trust Building on the Korean Peninsula: Turning Korea’s DMZ into a UNESCO World Heritage Site,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 8, issue 35, no. 2 Aug 30, 2010

- Nanyan Guo, “Environmental Culture and World Heritage in Pacific Japan: Saving the Ogasawara Islands,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol 7, Issue 17, no. 3, April 12, 2009.

- Miyamoto Takashi, “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 1, no. 31, Jan. 1, 2017.

Notes

長崎市平成28年版長崎市統計年鑑(統計表)-長崎市ホームページ (Nagasaki-shi Heisei 28 nenpan Nagasaki-shi tōkei nenkan (tōkei hyō) – Nagasaki-shi hōmūpeji / Nagasaki City Heisei 28 Year Publication, Nagasaki City Statistical Yearbook (Statistical Tables) – Nagasaki City Homepage), 167 – Atomic Bomb Museum entrants totals; 168 – Glover House and Garden entrants totals; 170 – Dejima entrants totals; 177 – Gunkanjima entrants totals (landings only). See here 端島上陸数(平成21年度―平成28年度) (Hashima jyōrikuzu (Heisei 21 nendo – Heisei 28 nendo) / Hashima Landings Totals – Heisei 21 fiscal year to Heisei 28 fiscal year), Nagasaki City Government Planning Department, World Heritage Promotion Office, March 2017.

A fifth far smaller tour boat operates from Nomozaki Peninsula on the coast, about an hour’s drive south of Nagasaki City.

“General situation of attendance numbers for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum” Accessed Dec. 28, 2017. Between 1955 (the opening of the museum) and 2015, there were 67,331,513 visitors in total. Between 2011 and2015 there was a 39.62% average increase foreigners visiting the museum.

For background on the rise of the international industrial and modern building heritage tourist industry, as well as problems related to accurate historical restoration of disused industrial sites and damaged wartime buildings, see for example, David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Hilary Orange, ed., Reanimating Industrial Spaces: Conducting Memory Work in Post-Industrial Societies (Walnut Creek, CA.: Left Coast Press, 2015); Harriet Deacon, “Intangible Heritage in Conservation Management Planning: The Case of Robben Island,” International Journal of Heritage Studies, (2004) 10:3, pp. 309-319; Olwen Beazley, “Politics and Power: The Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) as World Heritage,” in Sophia and Colin Long, eds., Heritage and Globalization (London: Routledge, 2010), pp. 19-44; and Olwen Barbara Beazley, “Drawing a Line Around a Shadow? Including Associative, Intangible Cultural Heritage Values on the World Heritage List,” Ph.D. thesis, Australian National University, 2006. Beazley writes about the highly politicized issues behind the World Heritage inscription of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial that divided the US and Japanese governments and publics. She addresses the problem of the absence of Koreans in Japanese historical presentations of the atomic bombing, which was only rectified in recent years when the memorial to Korean atomic bomb victims was finally moved into the peace park from its periphery following protests by Japanese and Korean supporters of hibakusha rights and critics of discrimination against Koreans. Note the large number of Korean hibakusha and explain their presence. For an assessment of Hashima as a World Heritage site advantageous to tourism, but an analysis that fails to consider historical controversies and the absence of substantial historical information at the site or at the ticket office area in Nagasaki port, see Atsuko Hashimoto and David J. Telfer, “Transformation of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island): From a Coalmine Island to a Modern Industrial Heritage Tourism Site in Japan,” Journal of Heritage Tourism, (2017) 12:2, pp. 107-124.

Photos by David Palmer, at Yawata Steel Works outdoor museum, Kokura, taken March 2015 five months before the site was World Heritage inscribed. The Yawata site, with historical information and restoration, was in place almost a decade before the World Heritage inscription of the site. This outdoor “historical park” is a result of local government efforts in conjunction with Sumitomo Corporation, which owns the property. Much of the site’s technology dates from Taisho and Showa, though the main blast furnace was built in the Meiji Era (1901).

See, for example, “Post Apocalyptic (industrial metal)” on YouTube. The classic example of this genre in hip hop is “The Message,” by Grandmaster Flash. For post-apocalyptic computer and online gaming stories, see “10 Best Post-Apocalyptic Games Where Human Civilization Collapsed” on YouTube. Accessed 7 Dec., 2017. The range of science fiction movies using this type of imagery is vast. Probably the most well known films are The Matrix series.

For the Gunkanjima scene in Skyfall, see here. The first part of the clip is the view of Hashima from the sea. The second part of the clip is shot at a different location but made to appear like Hashima. Moviegoers have no idea where the locations are unless they do background inquiries about the film. The extent to which this part of Skyfall has influenced tourists coming to Hashima has not been investigated.

Shim Sun-ah and Cho Jae-young “(Yonhap Interview) ‘Battleship Island’ director says disputes would only reveal the film’s true value,” Yonhap News Agency, Aug. 2, 2017. Accessed Jan. 3, 2018.

“The Battleship Island Trailer #2 (2017), Movieclips Indie,” YouTube. For comments by the director and actors that emphasize the movie as both entertainment and history, and how the movie has a major “celebrity” and “action” focus, see “INT[erview] for movie ‘The Battleship Island’: So Jisub, Song Joongki (Entertainment Weekly/2017.06.19),” YouTube. For background on the entire movie, see “The Battleship Island,” Wikipedia. For the Japanese movie Yamato, see the YouTube trailer. All websites accessed 6 Dec., 2017. It is worth considering comparisons of these type of movies with those made of the Battle of Stalingrad, one American – Enemy at the Gates, the other Russian – Stalingrad – both equally “action” oriented with fake romantic scenes in the middle of the war zone, both equally fictionalized history with a grain of truth, and both equally nationalist – the American one making the Soviet Communist Party and Soviet officers into total hacks, the Russian one just the opposite, as heroes.

The 2005 Japanese film Yamato was a box office success in Japan. See “Yamato (film),” Wikipedia. Accessed Jan. 3, 2018. On the construction of the Yamato and its use and final sinking in World War II, see Maema Takanori, Gunkan Yamato tanjō (Birth of Battleship Yamato – volumes 1 & 2) (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1997, 1999).

“Gunkanjima: Memories of Doutoku Sakamoto,” interviewed by Jordy Meow, Offbeat Japan, June 19, 2014. Accessed 22 Nov., 2017. At no point in the interview does Sakamoto criticize the Japanese government, instead directing his criticism at popular portrayals and general neglect.

Tze M. Loo, “Japan’s Dark Industrial Heritage: An Introduction,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 1, no. 1, Jan. 1, 2017 .

“Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention,” WHC.16/01 October 2016.

For background on Mitsubishi’s purchase and development of Hashima, as well as the company’s Nagasaki Shipyard, see David Palmer, “Nagasaki’s Districts: Western Contact with Japan through the History of a City’s Space,” Journal of Urban History, 2016, Vol. 42(3), pp. 477–505.

Takeuchi Yasuto, Senji Chyōsenjin kyōsei rōdō chyōsa shiryō shu (Wartime Korean Forced Labor Investigation Documents Volume: Supplementary Revised Edition (Kobe: Kobe Student Youth Center Publishing Department, 2015).

Kim Soong-il, “Kim Soong-il saiban no genjō,” in Yamada Shōtera and Tanaka Hiroshi (eds), Rinkokukara no kokuhatsu (Tokyo: Shōshisha, 1996), cited in David Palmer, “Foreign Forced Labor at Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki and Hiroshima Shipyards: Big Business, Militarized Government, and the Absence of Shipbuilding Workers’ Rights in World War II,” in Marcel van der Linden and Magaly Rodríguez García, eds, On Coerced Labor: Work and Compulsion after Chattel Slavery (Leiden: Brill, 2016), pp. 177-178. The probability of Chinese forced laborers being POWs from Japanese occupied Northeast China is based on the high percentages of Chinese used in Japanese coal mines from provinces there, as listed in Takashi Hiroshi, Utsumi Aiko, Niimi Takashi, Chronicle of Chinese Forced Laborers: Documents (Chūgokujin kyōsei renkō no kiroku: shiryō) (Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 1990), which reprinted a March 1946 Japan Foreign Ministry Report (with introductory analyses by Takahashi, Utsumi, and Niimi) of 38,935 Chinese taken from China to Japan for forced labor, and included full name, family register name, province of origin (and in some cases county and / or village of origin), age, and if deceased. The Hashima coal mine entry with specific names listed only 17 Chinese, 15 of whom were listed as deceased, with province of origin unknown except one. This obviously was a cover up by the Ministry, as it was the only coal mine in a national list of 155 that did not list a substantial number of Chinese with full details of province of origin. In contrast, Takashima Island coal mine (also owned by Mitsubishi), listed 205 Chinese (most likely a substantial undercount), with full name, province (a majority from Hebei, a center of Communist guerilla resistance to Japanese military occupation by the early 1940s), and a majority not deceased. For the use of Chinese POWs taken to Japan as forced laborers, see Ju Zhifen, “Labor Conscription in North China: 1941-1945,” in Stephen R. MacKinnon, Diana Lary, Ezra F. Vogel, eds., China at War: Regions of China, 1937-1945 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), p. 218.

Perhaps the best critical analysis of the cover up of Hashima’s real history and the problems this poses for World Heritage listing, particularly the failure to acknowledge fully the role of Korean forced laborers there, is Takazane Yasunari, “Should ‘Gunkanjima’ Be a World Heritage Site? – The forgotten scars of Korean forced labor,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 13, issue 28, no. 1, July 13, 2015; and Takazane’s Gunkanjima ni mimi o sumaseba: Hashima ni kyōsei renkōsareta Chōsenjin Chūgokuin no kiroku (If you listen carefully to Gunkanjima: Records of Korean and Chinese forced into labor at Hashima) (Tokyo: 2011). Takazane did not list his name as author of this book, but had it published under the auspices of the “Committee for the Protection of the Rights of Zainichi Koreans in Nagasaki”, which has worked extensively for the rights of Korean atomic bomb survivors. See also, William Underwood “History in a Box: UNESCO and the Framing of Japan’s Meiji Era,” The Asia Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 13, issue 26, no. 2, June 29, 2015. Accessed Dec. 15, 2017.

World Heritage Committee, UNESCO, “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining, Japan,” Decision: 39 COM 8B.14, Accessed Dec. 15, 2017.

Project Committee of Hashima Mine Closure’s 40th Anniversary, Ōki naru Hashima (Great Hashima) (Fukuoka, 2014), p. 2.

Details on these three sites and how the Japanese government planned to address World Heritage Committee recommendations are in “Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining (Japan)

(No. 1484), State of Conservations Reports by States Parties,” UNESCO documents for “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining, Japan,” 2015. Accessed 28 Nov., 2017.

World Heritage Committee, UNESCO, “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining, Japan.”

“UNESCO World Heritage Shirakawa-go: Traditional Houses in the Gassho Style, Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Historic Building,” Shirakawa-go Tourist Association, Ogun, Gifu Prefecture, 2013.

“Hajima (Gunkanjima),” Nagasaki Tourist Information Center (no other identifier on pamphlet), no date. Acquired by author in March 2017.

Gunkanjima Digital Museum, Nagasaki. Gunkanjima Concierge Company, Nagasaki. Accessed Dec. 15, 2017.

See “Candidate for World Heritage” list with descriptions and further details in “Churches and Christian Sites in Nagasaki,” Wikipedia For the initial nomination made in 2007, see “Churches and Christian Sites in Nagasaki,” UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List For the 2018 nomination list of twelve sites, see “Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region,” World Heritage Registration Division, Culture, Tourism & International Affairs Department, Nagasaki City Information on this controversy is based on confidential correspondence with Nagasaki contacts. All websites accessed Dec. 16, 2017.

Miyamoto Takashi, “Convict Labor and Its Commemoration: The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine Experience,” The Asia-Pacific Journal / Japan Focus, vol. 15, issue 1, no. 31, Jan. 1, 2017. Accessed Dec. 13, 2017.

In 2015 I toured the northern coal mining region of Kyushu (Chikuhō) with a Japanese colleague and our Korean-Japanese companion as guide, including the local museum in Tagawa, Fukuoka, and many memorial sites and cemeteries that included names of Korean miners.

David Palmer, “History Wars: Japan’s Industrial Heritage Listings Fuel Controversy over Korean Forced Labour in WW II,” Asian Currents, July 20, 2015.

Reiji Yoshida, “Government downplays forced labor concession in winning UNESCO listing for industrial sites,” The Japan Times, July 6, 2015; “Japan sites get world heritage status after forced labour acknowledgement,” The Guardian, July 6, 2015.

“Japan to publicize testimony denying that Koreans were forced to work ‘under harsh conditions’ at UNESCO-listed ‘Battleship Island,” The Japan Times, Dec. 8, 2017.

No Koreans or Chinese under 18 were taken to Japan as forced laborers during World War II. See ages of Chinese listed in Takashi Hiroshi, Utsumi Aiko, Niimi Takashi, Chronicle of Chinese Forced Laborers. The shortage of Japanese workers in industry led to the use of underage students (gakuto dōin) in factories and shipyards during the war, but no Japanese under 18 were used in coal mines.

“Japan to publicize testimony denying that Koreans were forced to work ‘under harsh conditions’ at UNESCO-listed ‘Battleship Island.”

“South Korea’s Moon speaks out on wartime forced laborers’ right to seek redress from Japanese firms,” Japan Times, Aug. 17, 2017. For South Korean Supreme Court decisions awarding damages to Korean forced laborers and their families, in which Mitsubishi and Sumitomo were defendants, see Palmer, “Foreign Forced Labor at Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki and Hiroshima Shipyards,” pp. 170-174. No litigations of this type have been successful in Japanese courts. Other Korean forced labor litigations involving other worksite locations in Japan continue in South Korean courts as of this writing.

Takeuchi Yasuto, Investigation: Korean Forced Laborers, volume 1 – Coal Mines (Chōsa: Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō rōdō (1) – tankō hen) (Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha, 2013), pp. 265-267.