Abstract: This article offers a critical assessment of J. Mark Ramseyer’s analysis of the wartime Japanese military “comfort women” system, “Contracting for sex in the Pacific War,” Closely examining the Japanese sources that Ramseyer cites, it finds the article flawed in distorting the evidence and in confusing the prewar system of prostitution and the wartime system.

Kusama Yasoo, Jokyū to baishōfu (Tokyo: Hanjinsha, 1930)

is one of the main sources Ramseyer used for his article.

1. Introduction

1-1. Problems with the Ramseyer Article

In his article “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War,” J. Mark Ramseyer lays out an interpretation of Japanese military “comfort women” that is contrary to the facts.1 Ramseyer’s argument is that the Korean women who became “comfort women” were their own agents on the contracts: they negotiated with the owners of the “comfort stations,” became “comfort women” by mutual consent, and earned a large amount of money. Although he concedes that among Korean “comfort women,” there were some who were deceived into working at the comfort stations, he argues that the brokers were Koreans and the comfort stations who employed and managed the women were privately owned and were only used, and not controlled, by the Japanese military.

There has already been a large amount of international criticism of Ramseyer’s argument about Japanese military “comfort women,” showing his inappropriate manipulation of historical documents.2 In this article, however, I want to show that the argument about Japanese military “comfort women” that I described above is not the only problem with the Ramseyer article. In it, Ramseyer deploys his claims not only about the issue of “comfort women” but also about Japan’s prewar prostitution system. They are both deeply related to historical revisionism on the issue of “comfort women.” The following is what I find problematic in Ramseyer’s assertions.

The first problem is Ramseyer’s insistence that under the prewar Japanese prostitution system, licensed prostitutes (shōgi) exercised agency when they entered into what he says was a mutually agreed-upon contract. “The women forced recruiters” to put their money behind promises in the contract, he wrote, by making them pay “each prostitute a large fraction of her earnings upfront,” and cap “the number of years she would have to work.”3

“[I]n cities like Tokyo, they could easily leave their brothels,” he writes.4 “[I]n practice, the prostitutes repaid their loans in about three years and quit”5 and “[S]he would have repaid her initial loan of 1,200 yen in about 3 years.”6 As these examples illustrate, Ramseyer claims not only that the licensed prostitutes were able to quit any time they wanted but also that their terms of work were short, their incomes were high, and they were able to easily pay back the loans they had received when they started working.

The second problem is Ramseyer’s claim that the contracts used between “comfort women” and the owners of comfort stations were the same as those used for karayuki-san, Japanese women who were sold into prostitution in Southeast Asia and other areas.7 As he writes, “the comfort stations hired their prostitutes on contracts that resembled those used by the Japanese licensed brothels on some dimensions.”8 In this way, Ramseyer terms “comfort women” as ”prostitutes,” and equates their contracts to those under which licensed brothels employed licensed prostitutes. In other words, his logic is that since “comfort women” were almost the same as licensed prostitutes, they must be working under the same conditions, including being able to exercise their agency in entering into contracts, to quit easily, and to pay back their loans since their incomes were high.

Let me explain how these claims are contrary to the facts and how Ramseyer justifies such false claims.

First, the contracts between licensed prostitutes and brothel owners were not based on an even relationship. The contracts were de facto human trafficking given the strong power relationship between women who could do nothing but become prostitutes, and the brothel owners. Such a power relationship also existed between licensed prostitutes and their parents because they were sold by their parents. Because the status of women in the family system in modern Japan was low,9 it was believed to be unavoidable for parents to sell their daughters when their ie or “household” faced a crisis. There are numerous personal notes written by former licensed prostitutes and geisha, as well as interviews with them. It is clear from these that their parents sold them to the owners of brothels and geisha houses.10 As I will explain later, licensed prostitutes’ incomes were so small that they were hardly able to pay back their debts and it was extremely difficult to quit at will.

Secondly, the licensed prostitution system in prewar Japan was not the same as the wartime “comfort women” system. The licensed prostitution system in modern Japan and its colonies and the “comfort women” system do have a commonality in that both were systems of sexual slavery. Yet, the “comfort women” system was different from the licensed prostitution system mostly because it was the Japanese military that established the comfort stations and recruited “comfort women.“ They were different also because, while many of the Japanese “comfort women” were licensed prostitutes, geisha and shakufu (barmaids) who were forced into the work, other women in Japan’s colonies and occupied areas who were forced to become “comfort women” had nothing to do with prostitution and were recruited without contracts by the Japanese military or by contractors instructed by the military, using violence, deceit and human trafficking. These facts have been proven not only by personal testimony but also with scholarship based on a huge amount of historical records including official documents.11

Thirdly, when he explains his own claims, Ramseyer did what a scholar ought not to do, which is to arbitrarily pick the parts in the materials and historical documents that are convenient for his own claims and to ignore those that are inconvenient. With abundant historical resources, scholarship has revealed the two points I raised above, that is, that (1) licensed prostitution contracts were human trafficking contracts, and (2) while both licensed prostitution and the Japanese military “comfort women” system were forms of sexual slavery, they were different in that the Japanese military “comfort women” system was a product of the military. Because it was difficult to disprove (1) and (2), Ramseyer tried to justify his argument with an unworthy act of selective scholarship.

1-2. The Purpose of this Article

Therefore this article aims to verify the sections in the Ramseyer article that discuss prewar Japanese licensed prostitutes and brothels by checking the documents and historical records on which he relies. I show how Ramseyer builds his argument by deliberately using only those parts of the documents and historical materials that are convenient for his argument while ignoring those that are inconvenient — an improper manipulation as a scholar — and prove that his article does not meet academic standards. Because the licensed prostitute contract in prewar Japan is the starting point for his discussion, it is meaningful to examine and criticize his view of it in order to show how his article on the problem of Japanese military “comfort women” falls short.

In the next section, I briefly explain findings from previous studies of licensed prostitutes’ contracts in Japan, and use them to examine Ramseyer’s argument regarding licensed prostitutes.

2. What are the Licensed Prostitutes’ Contracts?

2-1. Human Trafficking

While his revisionist claims about “comfort women” have been discussed in detail by scholars like Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Ramseyer’s claims about contracts for licensed prostitution have received less scrutiny. Under the licensed prostitution system in modern Japan, women 18 years or older would apply to the police for a license. To become a prostitute, both the woman and her parents or guardians needed to sign and seal the contract. The actual party to the contract was often the parents or guardians, not the woman herself. The contract set a term of service (the period of indenture) and she borrowed an advance called zenshakkin from the owner of the brothel. The money equivalent for the term zenshakkin had been called minoshiro or minoshirokin meaning “human collateral” or “ransom money” in premodern Japan, but was subsequently changed to zenshakkin (advance) in order to hide the fact of human trafficking.12 Women who became licensed prostitutes had virtually no freedom to quit and were forced to sell sex until they completed their term of service or paid back their advance.13

Moreover, prostitutes had to have permission from the police in order to leave the licensed brothel district (Article Seven, Item Two, Regulations for Licensed Prostitutes, which was rescinded in 1933).14 Brothel owners would obstruct women from exiting prostitution. When women brought their closing applications to the police, the police officers would sometimes try to convince them not to quit or would call the brothel owners.

Meanwhile, the owners took, as their own share, all or most of agedaikin (the fee for sexual services paid by customers). Therefore, the licensed prostitutes’ shares were extremely small and they had to keep repaying the advances from their small income. As a result, it was difficult to pay back the advances. While there were differences in repayment systems in different regions, in Yoshiwara, for instance, a prostitute’s share was 0.5 yen of the 2 yen fee, a quarter of the total. A certain percentage of that 0.5 yen would go to her monthly payment on the advance, the fukin (a kind of tax), and other obligations. The remainder was the allowance that a prostitute used to pay for clothes, make-up, hair styling and so on. The money that was left was so little that in many cases the women had to borrow more money, delaying their repayment and adding to their debts.15 Therefore, many people at that time shared an understanding that the licensed prostitute contract was de facto human trafficking.

2-2. Why did Human Trafficking Persist?

In principle, many of the contracts in prewar Japan mentioned above were found to be legally invalid. In 1872, the government issued the “Edict for the Liberation of Geisha and Prostitutes” (Grand Council Proclamation, No. 295) followed by the Ministry of Justice Law No. 22, which released geisha and licensed prostitutes from their contracts of indenture and invalidated all contracts for monetary loans. As a result, only prostitutes of their own “free will” were supposed to be licensed. And yet, as we have seen, many women who signed these contracts were pressured by their families and had little idea what they were signing.

In addition, in 1896, the Supreme Court issued a ruling invalidating “contracts to work for a set term” saying they imposed illegal physical restraint. In 1900, the Supreme Court also invalidated contracts that required prostitutes to work at brothels in order to repay their advances.16 The Regulations on Licensed Prostitutes (shōgi torishimari kisoku) established in 1900 stipulated that licensed prostitutes could exit prostitution at will at any time (free exit or jiyū haigyō).

Despite these rulings and laws, human trafficking persisted because the courts in Japan differentiated between “contracts for prostitution” and “contracts governing advances,” and regarded only the former as invalid. Since the brothels made women borrow the advances in order to force them to sell their sex and deprive them of their freedom, a contract that forced a woman to work in prostitution and one which covered the advance were nothing but a single contract for human trafficking. Nevertheless the courts saw them as two different contracts.17 And the courts decided that prostitutes must repay the advances even after they quit because the contract for the advances were valid even if the one for prostitution was not. As a result, it became almost impossible for licensed prostitutes to quit and the practice of human trafficking continued.

Kawashima Takeyoshi a prominent scholar of sociology of law in postwar Japan, analyzed prostitute and geisha contracts and stated “the relationship between geisha and prostitutes who were owned and their owners was that between humans who were bought and humans who bought them, in other words, slaves and slave owners,”18 and the courts’ precedents “ended up giving a certain legal protection for human trafficking.”19

2-3. The Violation of International Conventions and Domestic Laws

In fact, licensed prostitution contracts violated at least the following international laws that existed before the war: the International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children (1921), the International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women of the Full Age (1933, which Japan did not ratify), and the Slavery Convention (1926, which Japan did not ratify). Fuse Tatsuji, a lawyer in prewar Japan, said in 1926 that the custom under Japan’s licensed prostitution system might have violated at least the following domestic laws: Article 90 of the Civil Code (Legally binding agreements whose aims were contrary to the public order and morals were deemed void), Article 628 of the Code (When there is an unavoidable reason, either party can cancel a contract immediately even if both parties have agreed on a term of employment), and Article 708 of the Code (The party who loans money for an illegal reason cannot demand repayment).20

Even mainstream politicians, major newspapers, and the general public shared abolitionists’ views that the licensed prostitute contract was human trafficking and the licensed prostitution system was slavery.21 The League of Nations’ Commission of Enquiry into Traffic in Women and Children in the East who visited Japan in 1931 also criticized Japan’s licensed prostitution system.22 In fact, in the mid-1930s the Home Ministry’s Police Affairs Bureau itself equated the licensed prostitution system to slavery and considered its abolition.23 While revisionists typically offer the argument that the prostitution contract was legal and acceptable at the time, and contemporary scholars are applying anachronistic moral standards to the past, it is quite clear that the licensed prostitution contract was considered both morally and legally dubious at the time, both inside and outside of Japan.

3. Fact-Checking the Ramseyer Article

Let us move to fact check Ramseyer’s article, “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War.” In the section on licensed prostitutes, Ramseyer first describes the main points of the contract and then uses data to discuss the age of the prostitutes, the numbers of years of continuous work, their incomes, and the details of repayment on their advances.

3-1. Licensed Prostitutes’ Contracts

While he shows no actual contract in his article, Ramseyer explains the terms of the licensed prostitute’s contract as follows on page 2 of his article:

- The brothel paid the woman (or her parents) a given amount upfront, and in exchange she agreed to work for the shorter of (i) the time it took her to pay off the loan or (ii) the stated contractual term

- The mean upfront amount in the mid-1920s ranged from about 1000 to 1200 yen. The brothel did not charge interest.

- The most common (70-80 percent of the contracts) term was six years.

- Under the typical contract, the brothel took the first 2/3 to 3/4 of the revenue a prostitute generated. It applied 60 percent of the remainder toward the loan repayment, and let the prostitute keep the rest.

Ramseyer’s claims about the contract are based on the following works as cited in his footnote 2 on page 2: Fukumi Takao’s Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū,24 Kusama Yasoo’s Jokyū to baishōfu,25 Ōkubo Hasetsu’s Kagai fūzoku shi,26 Ito Hidekichi’s Kōtōka no kanojo no seikatsu,27 and Gei shōgi shakufu shōkaigyō ni kansuru chōsa.28 Let us look at the contents of the contracts published in these works.

Jokyū to baishōfu introduces three licensed prostitution contracts signed in 1911, 1914, and 1923. The contracts included in the book are the ones in 1914 and 1923 and are the same as those in the survey by Chūō shokugyō shōkai jimukyoku (The Central Office of Employment) since Kusama, the author of the book, also conducted the survey. Both Kōtōka no kanojo no seikatsu and Kagai fūzoku shi have a contract. First, let us look at the 1924 contract included in Joykū to baishōfu29 as well as Geishōgi shakufu shōkaigyō ni kansuru chōsa. The underlines are mine.

The contract

I hereby enter into the following contract for engaging in the work of prostitution at your establishment.

Article 1: I will stay at your establishment and engage in prostitution under your direction and supervision for a period of six years beginning on the date of registration in the licensed prostitute directory.

Article 2: I borrowed 2,400 yen from you.

Article 3: The cash advance mentioned in the previous article must be returned using the income I earn from the prostitute business.

(Provisions) The fee per night is two yen. 1.2 yen shall be your income and the remaining 0.8 yen is mine. 0.5 yen of this 0.8 yen will go to the repayment of my loan and 0.3 yen shall be my allowance.

Article 4: If I temporarily borrow money beyond the advance mentioned in Article 2,

or you pay for my expenses, I must pay back the money I owe you following the previous article’s provisions.

Article 5: You will pay for all expenses such as daily meals and necessary items for the room rented for my work, and I will pay for kimono for each of the four seasons and other necessary items for myself.

Article 6: I will pay for my own medical expenses if I receive treatment at any hospital other than Yoshiwara Hospital.

Article 7: I will provide all of my possessions as collateral for my advance and will not have control over them.

Article 8: If you sell your brothel to someone else or need to transfer me to another, I will follow your direction without objection from myself or my joint guarantors.

Article 9: If I escape, my joint guarantors will immediately search for me and make me go back to work, and I accept that my term of service will be extended for the number of days that I was gone.

Article 10: If I die, my joint guarantors will take my body and proceed to prepare for a funeral.

(Provisions) If the duties mentioned in the previous articles are not completed, you will take appropriate measures and my joint guarantors will pay the cost.

Article 11: If I violate this contract, I will be responsible for reimbursing you for any damage I cause.

Article 12: I agree that the Tokyo district court has jurisdiction over any lawsuits concerning this contract.

July 20, 1923

Father: Kuroda Hachibei

Mother: Kuroda Saki

Prostitute: Kuroda Take

Brothel: Andō Kinjirō

(all are pseudonyms)

We can see that there are many other agreed items besides the term of indenture, the amount of the advance, the distribution of income and the method of repayment that Ramseyer points out. All of them, where I have underlined above, deprive the licensed prostitute of her freedom. For example, (1) the licensed prostitute does not own most of her possessions since they are collateral for her advance (Article 7); (2) neither the prostitute nor her parents can oppose the owner’s will when someone else purchases the brothel she works at or if she moves to another brothel (Article 8). In addition, it is clear that the joint-guarantors were responsible if the prostitute escaped or did not fulfill her duties. (3) Her parents who are joint guarantors are bound to bring her back if she escapes, and the period of her flight will be added onto her term (Article 9).

The licensed prostitutes’ contracts included in the books that Ramseyer refers to in his article, such as Kōtōka no kanojo no seikatsu and Kagai fūzoku shi, include similar articles to the one shown above. Moreover, in the former, there are contracts which include articles like “the term of service will be extended when the prostitute fails to pay back her advance by the end of the term”; “The prostitute pays the entertainment tax if her customer does not”; “Her joint guarantors pay for the rest of her unpaid advance when the prostitute dies”; “Her joint guarantors repay the advance when the prostitute escapes.30 The contract included in Kagai fūzoku shi has an article that says “the owner of the brothel will confiscate all of her possessions if the prostitute is not able to repay the advance by the end of the term.”31

Nevertheless, Ramseyer completely ignores these articles that deprive licensed prostitutes of their freedom. He does not mention them at all in his article. Isn’t this because they are inconvenient for his argument that women made contracts with their owners on an equal footing and they can feel free to quit their jobs? Ramseyer writes that the licensed prostitutes “understood too that they could shirk or disappear” and “[I]n cities like Tokyo, they could easily leave their brothels.”32 The contracts provide no evidence of this; in fact, these terms omitted in Ramseyer’s analysis strongly suggest the opposite. It shows that it was hard for licensed prostitutes to exit the brothels.

Indeed, there must have been a wide range of contracts and the conditions for the licensed prostitutes might have improved in subsequent years, perhaps influenced by the movement for the abolition of licensed prostitution or by strikes conducted by the prostitutes themselves. Yet Ramseyer relies on the materials mentioned above. If the purpose of his article is to discuss the terms specified in the contracts, it is inconceivable that he would ignore parts of them just because they are inconvenient.

Meanwhile, Ramseyer writes that if women shirked or escaped, “the brothel would then sue their parents to recover the cash advance (a prostitute’s father typically signed the contract as guarantor). That this only happened occasionally suggests (obviously does not prove) that most prostitutes probably chose the job themselves.”33 What is Ramseyer suggesting here, and does it accord with what we know about this contracts and their context? Ramseyer seems to be implying that the fact that women infrequently escaped – even though the burden would fall on their parents, rather than on them as individuals, if they did – means that women were content to labor in brothels. But how do we know this? Ramseyer frequently cites Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū, which proposes the opposite argument: “Her parents or her closest relatives become her guarantors and, if the prostitute fails to pay back exactly the amount of the contract, they are collectively responsible and the collection of the debt is immediately legally enforceable. Therefore even if a licensed prostitute wanted to quit, it is difficult for her to do so unless she finished paying back her advance if she does not want to cause trouble for others.”34 In a later section, it continues, “Most licensed prostitutes try to pay what their parents ask no matter what pain they have to go through or embarrassment they have to endure. Every brothel owner unanimously praises these women saying ‘No one must be more thoughtful of her parents than licensed prostitutes’.”35 Anyone who studies modern Japanese history knows that family morality was imprinted onto the daughters. Because the contracts took advantage of this, the licensed prostitutes thought they could not distress their parents, who were their joint guarantors, and this emotional bond meant that they were not able to escape. Ramseyer entirely disregards this explanation, which is proposed in the very sources he cites.

In addition, Jokyū to baishōfu and Kagai fūzokushi, both sources on which Ramseyer relies heavily, say that complex circumstances went into making contracts so as to hide the reality of the licensed prostitute contract. This was because, as mentioned above, a contract forcing a licensed prostitute to work involuntarily was invalidated by the courts. As a result, an increasing number of brothel owners did not stipulate in official contracts (kōsei shōsho) that they were making women engage in prostitution but instead privately made a licensed prostitution contract.

As Jokyū to baishōfu explains, because a notarized contract could be legally enforced, it could come into play in a conflict between the prostitute or her parents and the owner. If a dispute arose over repayment of an advance, a court would likely rule a contract invalid if the owner provided a notarized contract that mentioned the woman was made to be a prostitute involuntarily since, as explained above, any contract forcing a woman into prostitution against her will was invalid. Because of this, brothel owners became more artful. Even when they used a notarized contract, the book says, they would take care to mention nothing about licensed prostitution, but rather made it merely a financial contract, consigning all wording related to a woman’s role and work conditions as a prostitute to a private contract.36

The licensed prostitution contract of 1923 shown above was in fact a private contract. Separate from this contract, Kusama says that the parties also signed a notarized contract, shown below.37

The financing contract (original)

I describe the contents of statements from each party as follows.

Article 1: On July 20, 1923, Andō Kinjirō lent 2,400 yen to Kuroda Hachibei and Kuroda Saki, and the latter parties jointly borrowed the money based on this contract (the names are pseudonyms).

One: The principal must be returned by August 20, 1923.

Two: Interest is 10% per year and Kuroda must pay this on top of the principal.38

Three: Even after the end of the term, Kuroda must compensate for any damage until the repayment is complete, following the interest rate agreed in the contract.

Article 2: Debtors agreed that this contract can be legally enforced immediately upon failure to repay the advance in the contract.

This contract entered into at the government office on July 20, 1923. I read it aloud to each party and they all agreed. Therefore with me they signed and sealed here as follows.

This notarized contract mentions only the repayment date, the rate of interest, and the legal enforceability in case of failure to pay. It does not say anything about making the woman serve as a prostitute against her will. It works for the brothel owner since there is no worry that a court could rule the contract invalid if something happens. Also, because it is notarized, it can be enforced without a court’s intervention. Yet, Kusama writes, “a question comes to my mind when I look at this notarized contract very carefully. It is the date of payment in item one of Article 1. The loan of 2400 yen to Kuroda was dated July 20, 1923; the repayment date was the following month, on August 20. They were given only 30 days. How could they repay a debt of 2,400 yen in one month, a sum they borrowed by selling their daughter because they were so poor? Needless to say, that’s impossible.” If this was the case, why did the contract provide such a short term for repayment? Kusama argues that brothel owners set a short term for repayment because prostitutes were legally entitled to quit their jobs at any time. “If [the date of payment] is set for a short term, say one month after signing the contract, brothel owners can legally seize the parents’ property immediately upon a prostitute’s quitting. They then postpone collecting the loan if the prostitute continues to work. The sharp sword of this obligation, and its potential execution as soon as a month after starting work, is always dangling over her head.” At the same time, as we saw previously, the women were forced to explicitly promise to carry out the duties of being a prostitute by signing a private contract. These were clever methods that brothel owners created as prewar courts regarded the prostitute contract as separate from the contract for the advance, and saw the latter as valid. In order to discuss the licensed prostitute contract, we have to consider not only the contract itself but also these circumstances.39

I also have to comment on Ramseyer’s descriptions of the amount of the advance, the term of service, and the interest. It seems that he described the average amount of the advances as between 1,000 and 1,200 yen in the mid-1920s40 because the most common amount was between 1,000 and 1,200 yen in Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū.41 However, that data is for licensed prostitutes in Tokyo and we should remember that the advances varied in different areas. The length of the term of service also depended on the area they worked.42

At the same time, Ramseyer’s claim that “brothels did not charge interest”43 is false, even in Tokyo. In Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū, upon which he relies heavily, author Fukumi writes “Although as a general rule brothels do not require interest be paid on the advance, there are places requiring 7.2% per year or 6% per year depending on the designated zone. Even in zones where no interest was charged, when a prostitute quits or changes owner, there are cases where they are charged 10% or 12 % per year.”44

3-2. On the Age of Licensed Prostitutes

Next, Ramseyer writes “If brothels manipulated charges or otherwise cheated on their term to keep prostitutes locked in debt, the number of licensed prostitutes would have stayed reasonably constant at least up to age 30.”45 To be clear, even if the brothel kept the term of service agreed to under the contract, making women work as prostitutes repay the debt itself was legally invalid.46

Citing Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū,47 Ramseyer writes:

“In 1925, there were 737 licensed Tokyo prostitutes aged 21, and 632 aged 22. There were only 515 aged 24, however, 423 age 25, and 254 age 27.”48

But the actual numbers cited in the book is the following:

|

Under 21—1,104 |

21 years old—737 |

22 years old—632 |

23 years old—631 |

|

24 years old—515 |

25 years old—423 |

26 years old—330 |

27 years old—254 |

|

28-29 years old—306 |

30-34 years old—185 |

35-39 years old—29 |

older than 40—6 |

In other words, Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū that Ramseyer refers to shows the numbers of licensed prostitutes who were not only older than 28 years old but also older than 40. The census found 526 licensed prostitutes who were older than 28, accounting for more than 10 percent of the total. But for readers of Ramseyer’s article it reads as if there were no licensed prostitutes older than 28. Meanwhile, Fukumi, the author of the book and an inspector in the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, wrote: “We have to recognize that those licensed prostitutes who were older than 30 years old numbered 220, which is significant when compared with the total of 5,152. We can imagine that numerous painful facts must exist behind these numbers.”49 Ramseyer ignored these inconvenient facts—the numbers of licensed prostitutes recorded in the material on which he himself relies—to justify his argument that women were not restrained by the brothels for a long time.

Another important point as far as numbers of licensed prostitutes is that there were 1,104 licensed prostitutes who were under 21 years old; it is clear that this age group was larger than any other. But Ramseyer omits this number. The Japanese licensed prostitution system allowed minors as young as 18 to become prostitutes, which means that their parents were de facto the contracting parties. The fact that a large number of licensed prostitutes were under 21 years old is indeed inconvenient for his view that the women negotiated and signed their contracts as their own agents.

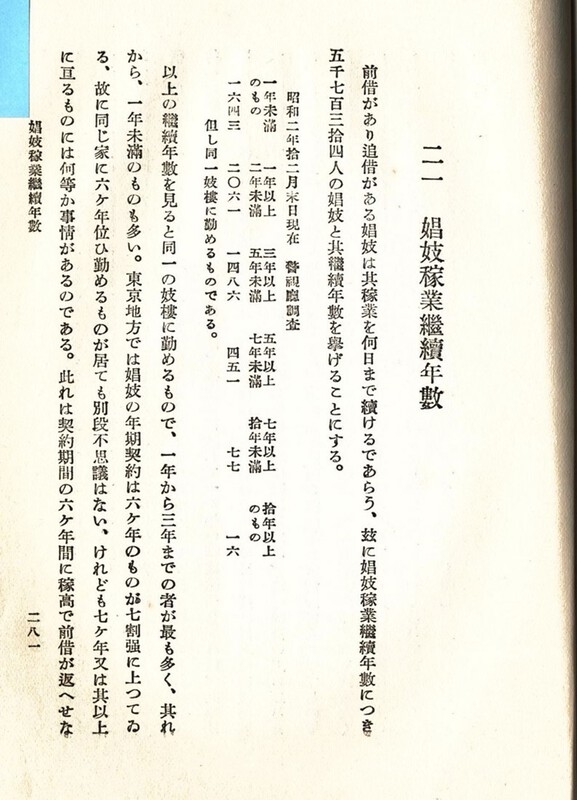

3-3. Prostitutes’ Years of Service

Moreover, Ramseyer states: “if brothels were keeping prostitutes locked in debt slavery, the number of years in the industry should have stayed constant beyond six. Yet of 42,400 licensed prostitutes surveyed, 38 percent were in their second or third year, 25 percent were in their fourth or fifth, and only 7 percent were in their sixth or seventh.”50 In other words, he insists that licensed prostitutes must have been able to quit after a short period of work.

But Ramseyer disregards an important description in the material he relies on. His citations include Ito Hidekichi’s Kōtōka no kanojo no seikatsu and Kusama Yasoo’s Jokyū to baishōfu. The latter reports the number of years of service for licensed prostitutes in Tokyo based on with a survey by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police as of the end of December in 1927.51

Survey by Tokyo Metropolitan Police as of December 31, 1927

*Provided that these are years worked at the current brothel.

|

Less than 1 year |

More than 1 year less than 2 years |

More than 3 years less than 5 years |

More than 5 years less than 7 years |

More than 7 years less than 10 years |

More than 10 years |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The number of licensed prostitutes |

1643 |

2061 |

1486 |

451 |

77 |

16 |

The number of years of service for licensed prostitutes in Tokyo as of December 31, 1927,

from a survey by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, as published in Kusama Yasoo Jokyū to baishōfu, 281.

Indeed, the number of licensed prostitutes who worked fewer than five years is large. Yet, what is important is the proviso which says “these are years worked at the current brothel.” Ramseyer does not mention this note at all in his article. In other words, in Jokyū to baishōfu, Kusama explains that these numbers do not reflect how many years the licensed prostitutes worked in total, but rather how many they worked at their current brothel. The data does not count years of service at any different brothel the women were subsequently relocated (sold) to. So while the chart shows that a majority worked fewer than two years at their current brothel, it is likely, given what we know about working conditions, that they were then transferred (sold) to another where they continued to work. In light of this, the chart tells us little about how easy it was for licensed prostitutes to quit.

3-4. Details of Exiting Prostitution

As noted above, Ramseyer says that licensed prostitutes were able to exit prostitution easily, but says nothing about the details of how women left. Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyū, another source that he relies heavily on, describes in its section on indenture:

“Opportunities for leaving prostitution receded because around the time their indenture was to end some prostitutes would be switched to a new brothel and become subject to a new contract.” 52

Kusama’s Jokyū to baishōfu, which Ramseyer relies on as seen above, includes a survey on the circumstances of prostitutes in one of Tokyo’s licensed quarters who exited the brothel.53 Below is a chart showing the research on the reasons for discontinuing service in Tokyo’s Suzaki Licensed Quarters in 1925 and 1926 (“Geishōgi shakufu shōkaigyō ni kansuru chōsa” also includes the 1925 survey).

|

1925 |

1926 |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Repaid the advance with earnings |

38 |

96 |

134 |

|

Relocated to another brothel |

113 |

50 |

163 |

|

Redeemed by a client |

28 |

22 |

50 |

|

Redeemed by parents |

21 |

34 |

55 |

|

Unpaid advance redeemed by the owner after finishing the term |

96 |

91 |

187 |

|

Unable to repay the advance |

24 |

72 |

96 |

|

Total |

320 |

365 |

685 |

While there was some variation by year, those who “relocated to another brothel” comprise the second biggest group (23.7%). As Kusama explains, these women did not exit prostitution but moved to or were bought by a different brothel where they continued to work as prostitutes. According to “Geishōgi shakufu shōkaigyō ni kansuru chōsa,” licensed prostitutes experienced impatience and distress and decided to move to other brothels for reasons including (1) not being able to earn enough money, (2) debts accrued because fathers, brothers or lovers asked for money, and (3) disadvantageous contracts that prevented them from paying down their debts.54

When a prostitute relocated of her own volition, her debt became subject to interest, which was retroactively charged back to the date she began working. In Osaka, a prostitute moving to another brothel was required to pay not only interest but also a penalty. Therefore, every time licensed prostitutes or geisha relocated, they accumulated more debt, making an exit from the business even more remote.55

At the same time, from the chart and Kusama’s explanation, we can see it was not easy for licensed prostitutes to quit when they wanted to and to repay their debts. Less than 20% of the women on the survey were able to repay their debts from their earnings.

Kusama also writes that the biggest group across the two years were those who were released by their owners “leniently” or onkeitekini even though they were not able to repay their advances within the contracted terms. In other words, absent the “leniency” of brothel owners, many licensed prostitutes would not have been able to quit. It was up to the owners not the women. Kusama also says, although it was “a custom of the licensed quarters” to “roll up the contract and free [the women] when the term of the contract ended regardless of whether their advance had been repaid,” those prostitutes who had not been able to pay back the debt when they finished the term had to give back their kimono and everything else they had purchased while they worked to help pay their remaining debt and “were free with nothing.”56

Kusama writes that there must have been quite a few prostitutes “who could earn more than 10,000 yen over six years,” more than the typical advance. “Despite that,” Kusama continues, “it is a pity that they still could not repay their debts by the end of their term of service, and were only freed from their cages through the leniency of the brothel owners.”57 In terms of “redeemed by parents,” Kusama explains that debt in this category was likely actually at least in part paid by clients.

These descriptions included in the materials on which Ramseyer relied go against in the argument that licensed prostitutes could easily exit the industry. He did not include them.

3-5. Licensed prostitutes were able to finish paying back their debts within three years?

Ramseyer says that a licensed prostitute’s yearly income averaged 655 yen in 1925, and considers that high. If the women allocated 60% (393 yen) of that amount to repay their debts, he claims, they would be able to repay a debt of 1,200 yen in about in three years. Although there is room to question whether his estimate of a licensed prostitute’s annual income or the amount of the advance are accurate, I am more interested in a different question.

Surely, there must have been some prostitutes who were lucky enough to pay back their debts in three years. Even if, however, they could quit working as a prostitute by paying back the debt in three years, the central fact is that the contracts were invalid and violated various international and domestic laws because they required them to work until the debts were repaid, as pointed out above.

Moreover, even if we estimate the yearly income for a licensed prostitute as he does, anyone can see that his reasoning that they must have been able to pay back their debts in about three years isn’t well-backed by the data. We cannot say anything unless we learn how much their expenses were. If there was more spending than income, as some reports make clear, their debts would pile up and they would not be able to repay.

What is certain is that many of the women faced extraordinary difficulty in repaying the debts; for many, the amount of debt rose as expenses outpaced earnings. And there is no way that Ramseyer could have missed this fact, which was emphasized in the materials that he deeply relied on for his argument. Yet he almost completely ignores this.

For example, “Geishōgi shakufu shōkaigyō ni kansuru chōsa” includes some cases in which their debts increased and decreased.58 Jokyū to baishōfu does as well. Let us look at one example from the latter.

In June 1917, a licensed prostitute began working at a brothel in Yoshiwara, receiving 650 yen as an advance and an additional 139.93 yen for chōkashikin or chōgashikin (money lent by the owner to pay for clothes and her futon, along with the fee for the recruiter59), which makes 789.93 yen in total.60 At this brothel, gyoku or gyokudai (the fee for sex with a client) is one yen. The brothel owner’s share is 0.7 yen while the prostitute’s is 0.3 yen. The total fees paid by her clients were 708 gyoku in her first five months. Of her 212.4 yen share, she assigned 141.60 yen to the repayment of her advance. This means that her repayment was going smoothly, but this did not last. Since she became a licensed prostitute at the start of the summer, she had prepared only summer kimono for work. In October she borrowed 234.3 yen to purchase winter kimono. That increased her debt to 883.43 yen, about 93 yen more than her original advance, Kusama notes. He says, “The brothel owner would encourage the girls to decorate themselves beautifully if they were popular and sell a lot of gyoku.”61

Fukumi also says that the debts kept piling up because many licensed prostitutes were not able to cover necessary expenses with their allowances. Expenses included: (1) miscellaneous items like cosmetics (2) kimono for work; (3) money for their parents; (4) sick days, and so on. He particularly emphasized the importance of (2). Licensed prostitutes had to change their kimono depending on the season, but few could cover that expense with their own money. The formalities of buying a kimono also merit attention, Fukumi says. “Prostitutes who did not have enough money to purchase a new kimono on their own often enlisted the help of the brothel owners. This opened them to malpractice like owners charging a 20 percent or 50 percent surcharge or forcing prostitutes to buy what they don’t want.”62

The descriptions above that emphasize how difficult it was for licensed prostitutes to repay their debts are certainly inconvenient for Ramseyer’s argument that they were able to repay their debts about for three years. That is why, here again, Ramseyer ignored the inconvenient facts in the materials on which he relies.

4. Conclusion

I’d like to conclude by making the following two points.

First of all, after checking the descriptions of licensed prostitutes in Ramseyer’s “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War” using the materials he relies on, I find that the article does not meet the standards of an academic article. On the content of the licensed prostitute contract, which is the basis of his essay, Ramseyer ignores evidence in the historical materials he supposedly relies on which reveals the deprivation of the licensed prostitutes’ freedom. He also constructs his claim in other parts of his article by ignoring numbers in the documents that are inconvenient to his argument, neglecting provisions and making an estimate which easily breaks down under scrutiny. We cannot say that an article like this, regardless of its theme, meets the requirements of an academic article.

Secondly, Ramseyer connects “licensed prostitutes” to “comfort women” by saying that both made contracts based on mutual agreement, their own interests, and consent. I’d like to point out that in reality the licensed prostitutes and the military “comfort” women were related in a very different way from what Ramseyer suggests. In the licensed prostitution system in prewar Japan, owners of brothels were able to trade licensed prostitutes, geisha, and barmaids under state authorization. It was this framework that enabled the Japanese military to use traders and recruit women widely when the war started. Japanese women who were licensed prostitutes, geisha or barmaids were sometimes forced to become “comfort women.”63 There were also many cases in which women with no connection to licensed prostitution were gathered through pretense or human trafficking under the direction of the Japanese Army.

Thus, the relationship between the “comfort women” problem and the licensed prostitution system sheds light on the terrible discrimination in modern Japanese society against women. The logic that “comfort women” were “licensed prostitutes” and “that’s why they were not victims” is not acceptable. Far from it. I have to say that this logic truly expresses an extremely low level of consciousness of human rights as well as a catastrophic indifference to scholarly standards.

Notes

Ramseyer, J. Mark. 2021, “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War,” International Review of Law and Economics, vol. 65, 1-8.

See Andrew Gordon and Carter Eckert, 2021, “Statement,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 19, issue 5, no. 14, 1-4.; Amy Stanley, Hannah Shepherd, Sayaka Chatani, David Ambaras and Chelsea Szendi Schieder, 2021, “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War”’: The Case for Retraction on Grounds of Academic Misconduct,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 19, issue 5, no. 13, 1-28; “Letter by Concerned Economists Regarding ‘Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War’ in the International Review of Law and Economics” (February 23, 2021) with more than 3300 signatures. Yoshimi Yoshiaki, a pioneer in the study of Japanese military “comfort women” problem, also posted a working paper titled “Response to ‘Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War’ by J. Mark Ramseyer” (working paper) on February 23, 2022 in SSRN.

For instance, Shirota Suzuko, Maria no sanka, (Tokyo: Kanita shuppanbu,2008); Mori Mitsuko, “Kōmyō ni megumu hi” (1926) in Tanigawa Kenichi (ed) Kindai minshū no kiroku 3 shōfu, (Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu ōraisha, 1971) and Harukomanikki (1927) (Tokyo: Yumani shobō 2004); Masuda Sayo, Geisha: kutō no hanshōgai, (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1995); Takeuchi Chieko, Shōwa yūjo kō, (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1989), Onioi, (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1990) and Hōzuki no mi wa akaiyo, (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1991); Miyashita Tadako, Omoigawa: Sanya ni ikita onnatachi, (Tokyo: Akashi shoten, 2010); Kawada Fumiko, Kōgun iansho no onnatachi, (Tokyo: Chikuma shobō, 1993) and others.

Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Jūgun ianfu, (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1995), Jūgun ianfu shiryōshū, (Tokyo: Otsuki shoten, 1992) and many others.

Kawashima Takeyoshi, “Jinshin baibai no hōritsu kankei (1),” Hōgaku Kyōkai Zasshi, vol. 68, no.7, 1951, 706 and 711.

Chūō shokugyō shōkai jimukyoku, “Geishōgi shakufu shōkaigyō ni kansuru chōsa” (1926), 35-51 and 127-132.

Kōhōgakkai (ed), Keikan jitsumu hikkei (Tokyo: Tokyo shuppansha, 52) says that prostitutes are not allowed to leave their designated brothel districts without permission.

Maki Hidemasa, Jinshin baibai, (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1971), 217; KawashimaTakeyoshi, “Jinshin baibai no hōritsu kankei (1),” 709-710; Wakao Noriko. 2011, “Jinshin baibai: sei doerisei o kangaeru” in Fukuto Sanae and Mitsunari Miho (eds) Jendāshi sōsho, vol. 1, kenryoku to shintai (Tokyo: Akashi shoten, 2011) 243.

Fuse Tatsuji, Kōshōjihai no senjutsu to hōritsu (Tokyo: Kōseikaku shoten, 1926), 32-33 and 40; Onozawa, Akane. 2015, “Seidorei sei o megutte” in Kikan sensō sekinin kenkyū, vol. 84, 8.

Naimushō keihokyoku, Kōshōseido Taisaku (1935) in Suzuki Yuko (ed), 1998 Nihon Josei undō shiryō shūsei vol. 9 jinken, haishō Ⅱ (Tokyo: Fuji shuppan). 248.

Ito Hidekichi, Kōtōka no kanojo no seikatsu, (Tokyo: Jitsugyō no nihonsha, 1931 [reprinted by Tokyo: Fuji shuppan, 1982]).

Although the payment date is set one month after the loan date (item 1, Article 1), the contract stipulates that the interest is 10% per year in item 2. We can understand from Kusama’s explanation the reason for this seemingly contradictory content, which is that it was recognized from the beginning that she would not be able to repay the debt in a month and would continue to repay it over many years.

The restriction of the terms of service for prostitutes started because “Commonly, once a woman sank into prostitution, it is hard to wash her hands of the business.” Yet, there were prefectures that did not limit the terms of service. Those prefectures included Hokkaido, Iwate, Akita, Saitama, Niigata, Toyama, Shizuoka, Mie, Saga, Kagoshima, and Okinawa. Prefectures that allowed brothels to extend terms when prostitutes borrowed more money over the course of their terms included Aomori, Miyagi, Yamagata, Chiba, Tokyo, Ishikawa, Nagano, Yamanashi, Gifu, Osaka, Totoro, Kagawa, Tokushima, Kochi, Fukuoka, Nagasaki and Miyazaki (Naimushō keihokyoku, “Kōshō to shishō,”1931 [Baibaishun mondai shiryō shūsei: senzen hen, vol. 20, Tokyo: Fuji shuppan, 2003], 76).

“Sensō to josei eno bōryoku” risāchi akushon sentā (Violence Against Women in War Research Action Center), Nishino Rumoiko, and Onozawa Akane (eds), Nihonjin “ianfu,” (Tokyo: Gendai shokan, 2015); Onozawa, Akane. “Geigi, shōgi, shakufu kara mita senjitaisei: nihonjin ‘ianfu’ mondai towa nanika,” Rekishigaku kenkyūkai, Nihonshi kenkyūkai (eds), “Ianfu” mondai o/kara kangaeru (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2014); Onozawa, Akane, “The Comfort Women and State Prostitution,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 16, Issue 10, no. 1, Article ID 5143, May 15, 2018.