Abstract: For almost two decades, Gunma Prefecture has been the site of an intense political struggle over the public representation of the history of wartime forced labor in Japan’s public sphere. Following an initiative by a private group, and with the unanimous consent of the prefectural assembly, a memorial dedicated to Korean wartime laborers was set up in a prefectural park in the city of Takasaki in 2004. However, in 2014, the prefecture announced it would not extend permission to maintain the memorial—a decision confirmed by Japan’s Supreme Court in June 2022. The debates in Gunma are illustrative of the rise of historical revisionism in twenty-first century Japan and the revisionist campaign to erase the term “forced labor” from Japan’s public sphere. The decision taken by Gunma Prefecture in 2014 to ban the memorial was a milestone, not only in this campaign, but also because it triggered massive media interest and encouraged other prefectural administrations to launch similar campaigns of censorship in public spaces.

Keywords: Japan, Historical Memory, Politics of Memory, Historical Revisionism, Wartime Forced Labor

On 15 June 2022, Japan’s Supreme Court dismissed the complaint of a citizen group over Gunma Prefecture’s decision to deny extension of approval for a monument dedicated to Korean wartime forced laborers.1 The monument, known as “Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship” (Kioku, hansei, soshite yūkō, see fig. 1), had been erected in 2004 in the prefectural park Gunma no Mori (Takasaki City) on the initiative of a group known as the Association to Build a Consolation Memorial for the Korean Victims of Forced Mobilization (Chōsenjin—Kankokujin kyōsei renkō giseisha tsuitōhi o tateru kai, 朝鮮人・韓国人強制連行犠牲者追悼碑を建てる会). In the 2010s, a right-wing anti-Korean group initiated a campaign to demolish the memorial which they claimed was based on “false history” and had a negative influence on Japan’s international reputation. In 2014, the prefectural assembly, which had approved the building of the monument in 2001, unanimously denied an extension of permission for it to remain in place. This decision sparked a nationwide controversy, fueled by inflammatory coverage in conservative media such as Sankei Shinbun, which in 2014 launched a column titled “History Wars” (rekishisen). A Gunma citizen group, which was formed to maintain the monument, challenged the prefecture’s decision and, in 2018, successfully sued Gunma Prefecture in Maebashi District Court, which ruled the prefecture’s decision “illegal.” However, the Tokyo High Court overturned this decision in 2021. The Supreme Court then confirmed the latter’s ruling, allowing Gunma Prefecture to take steps to demolish the monument.

Fig. 1: The monument known as Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship (Kioku, hansei, soshite yūkō), in the prefectural park “Gunma no Mori”, Takasaki, Gunma Prefecture. Photo by the author.

The controversy over the Gunma monument reflects the growing influence of historical revisionism in Japan—a political movement seeking to whitewash Japan’s wartime record and discredit voices that contain any hint of criticism of Japan’s wartime conduct. While this movement stands outside the profession of academic history in Japan, it wields considerable influence in politics, media, and among the commentariat.2 Emerging in the 1990s, but remaining a marginal force until the 2000s, the rise of conservative politician Abe Shinzō (1954–2022) of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) gave the revisionist movement a boost, as I have shown elsewhere.3 Abe’s appointment as prime minister for a second term in 2012 emboldened historical revisionists, resulting in a backlash against critical approaches to Japan’s wartime and colonial past.

On the question of Korean forced labor, revisionists argue that not all Korean workers were brought “forcibly” to Japan, that most were given contracts and were well paid, and that they were not treated particularly badly. Although the individual circumstances that brought Korean workers to Japan are diverse,4 revisionists allege that this recruitment activity was not only legal but that it was also profitable—for the workers. Labor mobilization in wartime Japan, they argue, was therefore very different from “forced labor” in Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union and thus the terms “forced labor”5 (kyōsei rōdō) and “forced relocation” (kyōsei renkō) should be avoided when referring to wartime Japan. While almost every history textbook used in Japanese schools in the 1990s, when historical revisionism was still a marginal phenomenon, contained information on “forced labor,” the campaigns waged by historical revisionists and pressure from the government subsequently forced most publishers to eliminate any mention of it from their textbooks.

This thorny issue gained international significance when in 2018 South Korea’s Supreme Court ordered two Japanese companies, both beneficiaries of Korean forced labor during the war, to pay compensation to individuals who had been subjected to labor conscription (chōyōkō) or their descendants. When the companies rejected the verdict, Korea threatened to confiscate their assets in Korea, which, in turn, caused a sharp reaction by the Japanese government, sparking a major diplomatic and trade row between Seoul and Tokyo. The issue is yet to be resolved.

Beyond specific issues like forced labor, historical revisionists also flatly deny that Japan was an aggressor in the Asia-Pacific during World War II (or the Asia-Pacific War, 1931–45).6 They have campaigned against memorials to the victims of coerced prostitution during the war, the so-called comfort women, an issue related to that of forced labor.7 The campaign against the monument in Gunma, is part of this broader development and is one manifestation of the phenomenon of “closing spaces” in Japan’s public domain for reflective and self-critical representations of Japan’s wartime past. This trend does not bode well for reconciliation in the East Asian region and may derail Japan’s ambitions to play a more active role in the international community.

Labor Mobilization in Wartime Japan

During the Asia-Pacific War, Japan recruited millions of additional workers through various mechanisms of labor mobilization.8 To achieve its ultimate objective of victory in the war, the government reallocated laborers, moving them from one sector of the economy to others where they were required, and from one region to another. This policy of mobilization and reallocation affected the whole Empire, including the colonial territories. In the last stages of the war, an increasing number of women were mobilized as well. Most of those recruited laborers were assigned work in their home region. Due to the increasing number of Japanese men being drafted for military service, however, workers from colonial territories were recruited in growing numbers to be sent to Japan, where they were allocated to mines or construction sites, compensating for the growing labor shortage. While some were recruited in accordance with the legal framework in place at the time, others were duped into signing contracts, and, towards the end of the war, many were conscripted into what was effectively forced labor.

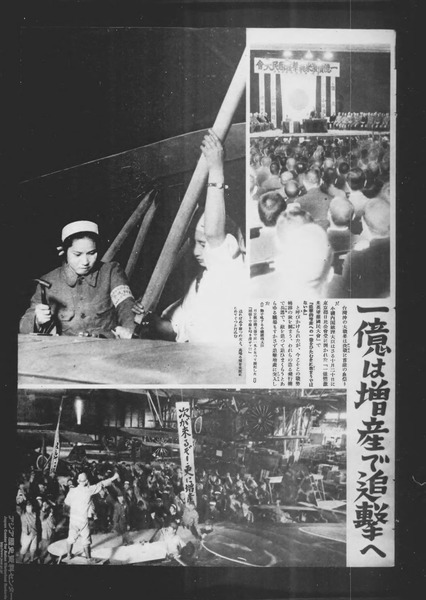

The 1938 Total Mobilization Law (Kokka Sōdōin Hō), enacted following the outbreak of total war in China in 1937, provided state authorities with legal instruments to control the labor market more closely than before. The law was also adopted by the colonial authorities in Korea, Japan’s most populous colony, and in other parts of the Greater Japanese Empire and was extended to territories occupied during the war.9 The message that every “subject of the Emperor” (shinmin), irrespective of ethnicity and gender, had to fulfil his or her duty was disseminated on a massive scale through state-controlled propaganda outlets (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Wartime propaganda encouraging labor mobilization. Source: Shashin Shūhō 341 (1 November 1944).

Until the late 1930s, restrictions were imposed on migration from the Korean peninsula to Japan, although settling anywhere in the Empire was a constitutional right. The Government-General of Korea (Chōsen Sōtokufu) sought to stem the loss of qualified sectors of the peninsula’s workforce,10 while the authorities in Japan feared that mass migration might endanger social cohesion and stability. In Japan, Koreans were viewed with suspicion and met with expressions of ethnic superiority from their hosts. Even representatives of industry were not convinced of the merits of labor migration from Korea. As late as in 1940 the Oriental Economic News (Tōyō Keizai Shinpō) warned that Koreans coming to Japan as laborers were unlikely to be “a healthy element in Japanese society” after peace was restored.11 The option of recruiting labor in Korea and other parts of the Empire was thus characterized by a high degree of ambiguity, whatever angle it was viewed from. However, whenever the war situation escalated and increasing numbers of young Japanese were drafted for military service, additional workers were urgently needed to compensate for the national labor shortage.12

In 1939 the Korean Government-General enacted the Labor Conscription Ordinance (Chōyō-rei), opening more avenues for relocating Korean labor to the Japanese islands. From that year, private companies could recruit (boshū) laborers for allocation to war-related industries. The system was seen as offering Koreans better employment opportunities, given the economic gap between Japan and the Korean peninsula. In fact, the economic gulf was so vast that Koreans were readily lured into applying for what seemed to be attractive jobs, while knowing little about what to expect. Under the boshū system, most of those recruited were assigned to work on the peninsula, but some were relocated to the Japanese islands and other colonial territories, such as Southern Sakhalin and the South Sea Islands. The relocation of workers was organized according to the Labor Mobilization Plan (Rōmu Dōin Keikaku) adopted every year by the Cabinet and aimed at determining the demand for labor in the various parts of the economy. The 1939 Plan mandated the relocation of 85,000 Korean workers to Japan,13 making it all too clear that these policies were designed to serve the state’s objectives rather than being driven by a desire to offer disadvantaged groups new economic opportunities. The fact that only 38,700 Koreans were recruited through the new system in its first year of operation, however, revealed a lack of enthusiasm on both sides. For many Koreans, the paperwork involved was too complicated, resulting in large numbers bypassing the official route and moving to Japan under their own steam—an option which was perfectly lawful, given that Koreans were legally “Japanese subjects.”14

Thus, the boshū system soon reached its limits—although in 1942 the annual target of recruiting 120,000 workers in Korea for relocation to Japan was almost achieved.15 After the outbreak of war with the United States and Great Britain in December 1941 and further escalation of the war throughout 1942, in early 1943 the Cabinet adopted a further form of labor mobilization known as recruitment through government mediation (kan assen).16 The kan element stands for officialdom, clearly signifying an increase in state involvement. While even specialized journals such as Korean Labor (Chōsen rōmu) warned that there was no surplus labor on the peninsula,17 under the kan assen system state authorities recruited increasing numbers of Korean workers for transfer to Japan. Companies designated as essential to the war effort could request a labor allocation which the government would pass on to the colonial authorities in Korea. Despite the reluctance of the Government-General of Korea, which had its own needs, the colonial authorities were bound to fulfill these requests. Thus, relocation of Korean workers to the Japanese islands increased under this system. To what degree relocation was forced is difficult to determine for each individual case.18 There is, however, no doubt that many Koreans found themselves in a situation where they were unable to quit their assignment, even when they faced an unexpectedly harsh working environment. For these reasons, “forced relocation” (kyōsei renkō) has become a standard term to describe labor policies under the Japanese Empire in the first half of the 1940s. The widespread usage of the term rōmusha in Japanese wartime documents also underscores the “forced” nature of the labor practices discussed here, given that the “mu” in rōmusha means duty or obligation.

In 1944, the war situation had become so desperate that military conscription was introduced in Korea (voluntary military service had been practiced since 1938). Young men who were not conscripted for military service were routinely conscripted as laborers (chōyō). While there was no fundamental difference in recruitment methods between kan assen and chōyō, numbers further increased under the latter system.19 According to official Japanese statistics, between 1942 and 1945 close to four million Koreans were mobilized through “recruitment,” “official mediation” and “conscription” within Korea, while a further million were sent to Japan as well as to other colonial territories (these numbers exclude military conscripts and recruitment that was kept off the books or remained largely in the hands of private recruiters, including the so-called comfort women).20 Similar recruitment campaigns were conducted in Taiwan and the Japanese-occupied parts of China, though the numbers in Korea were far higher than in these territories. It is these conscripted laborers who are today often characterized as “forced laborers” or “slave labor,” although not all of them were put in chains and given a forced passage to Japan. Nevertheless, Korean and Japanese historians, analyzing the testimonies of survivors, corporate archives and official sources, have established beyond reasonable doubt that Koreans “were brought as laborers [to Japan] with force and against their will.”21 Historian Tonomura Masaru cites, for example, a report on a case of recruitment in Korea, when the authorities had trouble finding sufficient laborers and had to resort to “forced” recruitment. Struggling to gather 64 men and missing the target of one hundred laborers, more than half of the recruits escaped on the way from the recruitment center to the port from where they were to be shipped to Japan.22

Recruitment methods aside, working conditions for these newly mobilized laborers were poor, to say the least. Many Koreans were sent to coal mines and construction sites and found themselves in highly dangerous environments.23 Laborers routinely had to endure maltreatment by foremen and suffered from malnutrition. Koreans were particularly affected by the latter, but also experienced racial discrimination by co-workers and foremen.24 Notwithstanding the high-sounding wartime rhetoric of Pan-Asianism promoting the “Unity of Japan and Korea” (naisen ittai), there is no indication, as historian Tonomura Masaru argues, that those Koreans mobilized and brought to Japan were treated as “compatriots” (dōwan) or that their contribution to the war effort was genuinely appreciated. They were viewed with suspicion, considered troublemakers, and subjected to a high degree of surveillance. They were kept away as much as possible from the Japanese population and considered temporary Gastarbeiter who would be returned to Korea as soon as the war was over.25

Although Korean workers were paid, their wages were usually lower than those of their Japanese counterparts, and their salaries were often withheld. Quitting one’s job was not an option.26 In the last two years of the war, contracts were compulsorily extended.27 More and more workers tried to flee their assigned workplace, starkly illustrating the coercive character of the labor mobilization system. Almost 35% of those working in the mining sector made at least one attempt to escape their workplace, and group escapes were frequently documented in the last two years of the war.28 Unexpectedly harsh working conditions was the most common reason for worker flight as well as labor disputes.29 As we know from multiple ministerial reports, the government was well aware of the conditions under which conscript laborers were working—as well as the repercussions of their absence on their local communities and the families they had left behind.30 Though reliable numbers are not available, historian R. J. Rummel estimates that 60,000 Koreans died as a direct result of their recruitment as wartime laborers.31

Attitudes to Wartime Labor Mobilization in Postwar Japan

In 1945, when the war ended, there were more than two million Koreans in the Japanese islands. This figure includes families who had relocated to Japan before the war (ca. 800,000 Koreans had migrated to the Japanese islands before 1938) as permanent residents, as well as laborers relocated to Japan under the wartime mobilization system. While about half this number were repatriated in the years following the war, close to one million remained in Japan (or returned to Japan after being repatriated to Korea).32 Following the enactment of a new constitution in Japan in 1947 and the declaration of independence of Korea (North and South), Koreans living in Japan were deprived of their Japanese nationality and became aliens in the land in which many of them had been born.33 Even today, the status of many ethnic Koreans settled in Japan, many third or fourth generation, remains problematic and racial discrimination continues to affect their lives.

Wartime labor mobilization and the question of compensation did not become an issue for the Japanese government until 1965, the year in which Tokyo and Seoul established diplomatic relations after signing the Treaty on Basic Relations.34 The two governments also signed the Agreement Between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation, which stipulated that “the High Contracting Parties confirm that the problems concerning property, rights, and interests of the two High Contracting Parties and their peoples (including juridical persons) and the claims between the High Contracting Parties and between their peoples … have been settled completely and finally.”35 Promising Korea economic aid, the agreement ruled out the possibility of compensation or reparations for wartime injuries, both collective and individual.

The Japanese government continues to insist that all claims relating to the treatment of Korean laborers in wartime Japan were settled under the 1965 Agreement. When in 2018 Korea’s Supreme Court ordered two Japanese companies—Nippon Steel Corp. and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd.—to pay “consolation money” to wartime laborers, Japanese foreign minister Kōnō Tarō criticized the court’s decisions as violating Article II of the 1965 Agreement and inflicting “unjustifiable damages and costs on the said Japanese company.” He argued that, “Above all, the decisions completely overthrow the legal foundation of the friendly and cooperative relationship that Japan and the Republic of Korea have developed since the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1965.”36 In addition, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) issued a “fact sheet” asserting that the Korean Supreme Court’s decisions “pose a serious challenge to the post-war international order.”37 Given that in 1959 the Japanese government estimated that the number of conscripted laborers from Korea and still residing in Japan amounted to no more than 245 (sic),38 it seems highly questionable that the issue of conscript labor can be considered to have been resolved under the 1965 Agreement, because that the numbers involved were clearly much higher. But even in Korea, the issue was—and remains—disputed. In 2021, the Seoul Central District Court dismissed claims brought by 85 victims of forced labor, seemingly confirming the Japanese position while doing nothing to resolve the continuing bilateral controversy.39

However, not all Japanese companies have flatly rejected claims for compensation for wartime forced labor. In the 1990s, Nippon Steel and other companies paid “consolation money” to former conscript laborers from Korea.40 In the 2000s, several companies paid reparations to Chinese laborers.41 Although China had waived claims for reparations when the Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC) established diplomatic relations with Japan in 1972, in 2000, following a celebrated settlement, Japanese construction company Kajima paid compensation relating to wartime workers in its Hanaoka mines.42 In 2009, Nishimatsu Construction Corp. agreed to pay compensation to victims of forced labor after a decade-long legal dispute. In the settlement, Nishimatsu agreed to set up a trust fund of 250 million yen, out of which 360 Chinese, who were taken to Hiroshima Prefecture in 1944 to work on the construction site for a hydroelectric power plant, or their descendants, would receive “consolation money.” The fund was also used to set up a memorial and hold “consolation” services.43 This monument was unveiled in 2010 and has since become a site to commemorate forced laborers brought to Japan during the war.44 Revealingly, even companies from the Mitsubishi group have paid compensation to Chinese laborers and even set up memorials. For example, in 2021 Mitsubishi Materials (formerly Mitsubishi Mining) built a memorial in Nagasaki containing the names of 845 wartime laborers. Prior to that, the company had paid compensation to victims of labor mobilization campaigns and had also built memorials at the sites of former mines in Akita, Fukuoka, and Miyagi Prefectures.45

With regard to Korea, however, both the Japanese government and the corporate sector have taken a tough stance on the issue since the 2000s. This has to do with the fact that Korea is a minor economic partner compared with China, but also with legal interpretations. The Korean Supreme Court’s 2018 judgment was based on the assumption that Japan’s “colonial rule of the Korean peninsula was illegal,”46 an interpretation that Japan’s political establishment has strongly rejected since the start of bilateral negotiations in the early 1950s.47 Although some Japanese lawyers, such as Totsuka Etsurō, argue that the legal status of the 1905 and 1910 treaties, through which Japan turned Korea into a part of its Empire, was highly doubtful,48 the debate continues to dog the bilateral relationship. If anything, in recent years the positions of the two governments have become increasingly polarized, a situation reflected in a wide range of disputes over historical matters relating to the question of wartime labor.

One pertinent example are the discussions surrounding a number of sites in Japan pegged for UNESCO World Heritage and UNESCO Memory of the World status.49 Japan boasts 23 UNESCO World Heritage sites, more than any Asian country apart from China, India and Iran.50 During Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s second term as prime minister (2012–20), a number of sites were promoted that embodied ambiguous historical legacies. Like many other nations, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Japan adopted and internalized ethno-political concepts of racial hierarchies and imperialist domination. Today, the universal validity—or acceptability—of such notions has been called into question, to say the least. In many non-Western—and even some Western—countries, these nineteenth-century beliefs are now identified as promoting global inequality, imperialist—or neo-imperialist—exploitation, and discriminatory treatment of ethnic minorities. Attempts to revive these values face considerable resistance and trigger intense counter-reactions around the globe, including Japan. It was against this backdrop that the Abe government’s attempts to promote Japan-centric views of the country’s past in its international relations faced intense scrutiny and opposition—extending to projects submitted as candidates for UNESCO World Heritage and UNESCO Memory of the World status.

In 2016, UNESCO agreed to add the “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” to the list of World Heritage sites.51 The choice of “industrial sites” was a move that mirrored global developments. All over the world, local and national governments have rushed to extend heritage protection to historical sites associated with modern industrial development.52 Until the 1970s, “heritage preservation” had been focused on ancient and medieval sites. The idea that the remnants of early industrialization—sites dating to the nineteenth or even twentieth century—were also worthy of legal protection only emerged in the 1980s. In the 1990s, nineteenth-century industrial works were recognized as historical sites for the first time by local and national governments. UNESCO soon embraced this trend. In 1994, for example, it added Völklingen Ironworks in Germany, a nineteenth-century site, to the World Heritage list. Two years later, the first modern Japanese site was added to the UNESCO list—the famous A-Bomb Dome in Hiroshima, built in the 1910s but representing the tragic history of World War II.

The 23 sites listed by the Japanese government in 2016 as the “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” included coal mines, furnaces, ironworks, and shipyards. They seemed to match the new global trend for preserving the history of nineteenth-century industrialization and formed a much-needed addition to the Tomioka Silk Mill—a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2014, representing the early growth of Japan’s textile industry. However, other agendas were at work. The use of the term “Meiji” in the title, referring to the reign of Emperor Meiji from 1868 to 1912 (as well as being the posthumous name given to the reign of Emperor Mutsuhito), exhibited a strong ethnocentrism, given that outside Japan most people would not understand the significance of the term.

This nativist element aside, the list included sites that were hardly related to the historical industrialization of Japan. Take, for example, “Hagi Castle Town.” Hagi played a major historical role as the home of political activists who overthrew the shogunate in what is known as the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Nobody, however, even in Japan, would identify the city as a significant industrial area—or a city having any particular significance after 1868. The inclusion of the term “castle town” in the official designation indicates that the historical value of Hagi lies in the period before the Meiji era, when castles were important signifiers of feudal power.53 Yet, as a castle town, Hagi is no match for a number of other Japanese cities, some having castles which are listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites and whose “universal value” is widely recognized; the most prominent example is Himeji Castle in Hyōgo Prefecture. While the UNESCO requirement for “outstanding universal value” is listed—almost conspicuously—as the top item on the official homepage of the Sites,54 the particular merits of Hagi Castle Town remain unclear and are nowhere explained in the documentation. Critics suggested that the inclusion of Hagi in the list was a result of pressure from Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, who hailed from Yamaguchi Prefecture, where Hagi is located.

Likewise, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the Academy under the Pine Trees (Shōka sonjuku), a private school also located in Hagi, was included in the list for parochial interests rather than “outstanding universal value.” Notwithstanding the fact that this academy closed before the start of the Meiji period, thus lacking a direct connection to the “Meiji Industrial Revolution,” it was the site where one of Abe’s personal heroes, the nineteenth-century samurai-scholar Yoshida Shōin, lectured the members of the anti-shogunate movement, opening the way for the Meiji Restoration. While the historical significance of Yoshida and his school in this respect is undisputed,55 he and the movement he helped instigate have no links to the industrial revolution of the Meiji period and are thus irrelevant to the overarching global theme of nineteenth-century global industrialization. Little wonder that the official website “Meiji Industrial Revolution” fails to note any connection.56

Fig. 3: Screenshot from the website “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. Iron & Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining Inscribed on the World Heritage List.”

Another issue with the Sites is the question of authenticity. Authenticity is a widely—if not universally—accepted value in the context of heritage preservation and also a requirement of UNESCO. Oddly, among the 23 sites of the 2016 package discussed here, only a handful feature structures built before 1912, the end of the Meiji period, which gives the heritage package its name. On the small island of Gunkanjima (Battleship Island) near Nagasaki, which is home to the Hashima Coal Mine, none of the existing structures dates from before 1912. In contrast to its “flexible” approach to the evaluation of the historical importance of this site, Japan has rejected concerns that the documentation it has provided lacks any reference to conscripted or forced labor, arguing that no forced laborers were working in the mines before 1912. However, for the Meiji period, the question of whether forced labor was recruited for the Hashima mine boils down to one’s interpretation of the term. But even at this time, contracted laborers were forbidden from leaving the island. More importantly, there is no doubt that forced laborers, both Japanese and Korean, were used there during the 1940s. The Japanese government, however, has consistently rejected criticism from Korea about the UNESCO nomination, arguing that the significance of the sites lies in their status as witnesses to Meiji-era industrialization—and no more.57 Following Korean objections, however, UNESCO made the acceptance of Japan’s application conditional on the acknowledgement of forced labor in the mine; grudgingly, Tokyo agreed to add signage about this at the relevant sites. The narrative that visitors to the site are exposed to, however, strikes a rather nostalgic tone, as David Palmer explains. Even though Gunkanjima was infamous for its poor working conditions, the island’s industrial history has been thoroughly romanticized: “an illusion of a wonderful past of a close-knit community now lost but at least not forgotten.”58

The reality that working conditions in Japan’s mines were harsh—even in the Meiji period, which the UNESCO world heritage website celebrates so candidly—cannot be doubted. Japan’s industrial conglomerates (zaibatsu), including Mitsui and Mitsubishi, were infamous for the maltreatment of workers. From the turn of the century onwards, during the late Meiji period, miners frequently went on strike, protested working conditions, and sought to escape from their contractual obligations and slave-like labor conditions. During the war, not only Korean conscript labor, but also Australian and Chinese prisoners-of-war were sent to work in Japan’s mines, including those run by Mitsui and Mitsubishi.59 Labor disputes remained frequent until the postwar period, culminating in the famous Miike Coal Mine Strike of 1959–60.60

The Japanese government added insult to injury when it opened the “Industrial Heritage Information Center” in Tokyo in 2020 where the information panels fail to mention forced labor and avoid references to the harsh working conditions in mines. In a highly provocative move, the Center presents “testimonies from second-generation Korean-Japanese residents claiming there was no discriminatory treatment of Korean workers.”61 This approach generated negative coverage in the international press and led to an official protest from South Korea, alleging a violation of Japanese promises made to UNESCO. Seoul requested UNESCO to withdraw World Heritage status from the sites listed by Japan to commemorate its industrial revolution. In response, in 2021 UNESCO adopted a resolution stating that “Japan has failed to provide a sufficient explanation regarding the Korean victims of wartime forced labor” in its documentation at the Tokyo Information Center.62 The issue remains a thorny one in Japanese–Korean relations.63 Furthermore, again in 2022, the dispute was replicated when Japan submitted a recommendation to nominate the Sado Gold Mines for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2023. Here, once again, although forced laborers from Korea were exploited in the mines during the war, the Japanese government has passed over these dark chapters of its industrial history in both its application to UNESCO and its documentation of the site.64 As a result, South Korea has called for withdrawal of the nomination.65

Gunma’s Demolition Men

During the Asia-Pacific War, thousands of conscript and forced laborers were brought from Korea to Gunma to work in mines, on construction sites, and in factories. Estimates range from 6,000 to 9,000 or possibly more, plus a few thousand laborers from China.66 The workers were assigned, for example, to the construction of underground factories for the Nakajima Aircraft Company, a major supplier of warplanes for both the Japanese Imperial Navy and the Army.67 After several Nakajima plants in Gunma had been destroyed by US air raids in February 1945, laborers were assigned to build underground factories. This work was completed in July and the plants fitted out, but production was halted by Japan’s defeat in the war.68

Workers from Korea and China were also recruited for railway construction, including the Agatsuma Line, for the building of airfields, and for the construction of the Iwamoto Hydroelectric Power Plant, which began in 1944 and would not be completed until 1949. The corporate history of the company that built the power plant, Hazama-gumi, published in 1989, notes:

Forcibly relocated (kyōsei renkō) Koreans and Chinese were mobilized for the construction work. The Koreans were recruited in Korea by the company’s Labor Division (rōmuka). The number of Koreans mobilized amounted to around 1,000. The Chinese were POWs (furyo) captured in China and numbered 612, though six died on their way to Japan due to illness. … Because of the harsh nature of the work (kasan na sagyō), laborers continued to die. Forty-three Chinese died. Unable to cope with the poor conditions, increasing numbers of Koreans and Chinese escaped.69

The company history summarizes: “It is clear that without the conscription of Korean labor from the Korean peninsula and from within Japan, there would have been no progress with construction work in the final stage of the war.”70

A discussion of Koreans working in Japanese mines is also found in the official history of the village of Kuni, published in 1973. According to this account, at least 300 Korean conscript laborers (chōyōkō) were brought to work in the mines of this remote part of the prefecture. Conditions in this area must have been harsh, and the text states that 60 of these workers, mostly older men, were “unable to perform.”71

The presence of forced laborers from Korea as well as from China in Gunma thus was well established by the 1990s. Company histories, local (village) histories, and prefectural sources made available following a request by civil society groups in 1991 confirmed that wartime labor recruitment was historical fact beyond doubt.72

In 1998, an NGO was established to set up a memorial dedicated to the Korean laborers who had died in Gunma during the war—the Association to Build a Consolation Memorial for the Korean Victims of Forced Mobilization (Chōsenjin—Kankokujin kyōsei renkō giseisha tsuitōhi o tateru kai, hereafter Tateru-kai). The group considered it an urgent task to erect such a memorial to counter the collective amnesia affecting the memory of forced labor in Japan. In building the memorial, the group wanted to achieve the following objectives: to commemorate the victims of wartime labor mobilization; to memorialize this chapter of Japan’s national past and pass it on to the next generation; and to foster reconciliation with Japan’s neighbors.

In 2001, the group received approval from Gunma Prefecture to set up a memorial in the prefectural park Gunma no Mori in Takasaki City, with the decision to be reviewed after ten years. Approval came with certain conditions, including a request to avoid the term “forced relocation” (kyōsei renkō), which the prefecture demanded following consultations with the national government and, in particular, MOFA. Based on available sources, the prefecture argued, “it is not at all clear when [these] Koreans came to Japan, how many came to Japan” and where to “draw the line between forced labor” and “voluntary” labor migration.73 After a fierce dispute with the prefecture, the Tateru-kai eventually accepted this condition. The terms “forced labor” and “forced relocation” are thus not included in the inscription on the memorial. The monument, which was entirely financed by donations,74 was named “Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship” (Kioku, hansei, soshite yūkō), mirroring the objectives of the organization, but somewhat obscuring the original intention of those who proposed its construction. The Tateru-kai even had to rename itself the Association to Build a Consolation Memorial for the Korean Victims of Labor Mobilization (Rōmu dōin Chōsenjin giseisha tsuitōhi o tateru kai) to avoid the term “forced relocation.” After the memorial was completed, the group underwent a second change of name, becoming the Association to Protect the Memorial of “Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship” (“Kioku, hansei, soshite yūkō” no tsuitōhi o mamoru kai, hereafter, Mamoru-kai).

Metal plaques on the back of the rather unspectacular monument (fig. 1) carry the following inscription in both Japanese and Korean:

For part of the twentieth century, our country ruled Korea as a colony. In the last war [World War II / Asia-Pacific War], many Koreans were mobilized [to work] in mines, military factories, and other sites throughout the country in response to the government’s labor mobilization plans. Here in Gunma, too, due to accidents and overwork, precious lives were lost in no small numbers.

Now that we have reached the twenty-first century, we declare our firm resolve to inscribe the historical facts of the great harm and suffering caused by our country to Koreans deeply in our collective memory, to reflect in our hearts, and not to repeat these mistakes.

Not forgetting the past and looking towards the future, we want to deepen and renew mutual understanding and friendship through the building of this memorial for the consolation of the Korean victims of labor mobilization. We hope that the feelings inscribed on this monument will be passed on to the next generation, further encouraging the growth of peace and friendship in Asia.

24 April 2004

Association to Build the Memorial “Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship”75

The site was chosen because the 26-hectare park was the location of a wartime munitions factory, the Second Tokyo Army Factory (Tōkyō Daini Rikugun Zōheisho), one of the many industrial sites in the prefecture where Korean laborers were placed during the war. Remains of the factory can be found right behind the memorial, although they are almost inaccessible—behind multiple fences, bamboo groves and lots of spider nets (see Figure 4).76

Fig. 4: Remains of the Second Tokyo Army Factory in the park Gunma no Mori. Photo by the author.

The erection of this monument was firmly in line with international developments. Forced labor had become a concern of various states by the 1990s. In 2000, the German Bundestag had passed the “Law on the Creation of a Foundation ‘Remembrance, Responsibility and Future.’” The similarity of the name of the foundation to the Gunma memorial is no coincidence, as debates regarding Germany’s attempts “to come to terms with its past” are frequently covered by Japanese mass media. The German foundation’s main responsibility was to provide for “individual humanitarian payments to be made to former forced labourers and other victims of National Socialism.” It mainly targeted former forced laborers from Eastern Europe, who, due to the Cold War, had been cut off from potential compensation by West Germany until the 1990s. But even after these payments had been completed, it remained active. Today, the foundation aims to keep “the memory of National Socialist persecution alive, to accept responsibility in the here and now, and to actively shape it for the future and for subsequent generations.”77 In 2021, it published an Agenda for the Future, detailing its forthcoming activities.78 In addition to this foundation, in 2006 the Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center was established in Berlin-Schöneweide, on the former grounds of an “almost completely preserved forced labor camp.”79 The Center, which is supported by the German Foreign Office, hosts exhibitions and serves as an educational site for schools and other groups and individual visitors. Because large numbers of forced laborers died in Germany during the war, many cities have erected memorials to commemorate them or maintain cemeteries where they are buried. Westhausen Cemetery, in a suburb of Frankfurt am Main, for example, is the site of an Italian cemetery with more than 4,000 graves. Many of those buried here were POWs or forced laborers who died in the last years of the war, when Italy had joined the fight against Nazi Germany.80

Fig.5: Italian War Cemetery in Westhausen Cemetery, Frankfurt am Main. Photo by the author.

Notwithstanding these developments in Germany—and elsewhere—historical revisionists in Gunma were not slow to oppose the idea of a monument dedicated to Korean laborers. Some voiced doubts about the historicity of the issue, while others claimed that even if Korean laborers had been brought to Gunma, they were probably well-paid and not treated particularly badly. Even though the final monument does not use the terms “forced labor” and “forced relocation”, this compromise did not dissuade revisionists from characterizing it as an expression of “false history” (kyogi) erected by “anti-Japanese” (han-nichi) elements—a common slur used by the right to discredit anyone voicing critical views of Japan and the nation’s history.81

Unable to prevent the erection of the monument, historical revisionists began a vociferous campaign for its removal in the late 2000s. Advancing a right-wing and anti-Korean agenda, the Gunma branch of the Do Better Japan! National Activities Committee (Ganbare Nippon! Zenkoku kōdō iinkai, hereafter “the Committee”) pressured the prefectural government not to extend its permission for the monument beyond the ten-year trial period.82 The Committee’s objections focused on the ceremonies held at the monument, arguing that they constituted a violation of one of the conditions set out by the prefecture—namely, that the memorial shall not be “used for political purposes.” In their “greetings,” some of those involved in these ceremonies, the critics claimed, had demanded that the Japanese government “establish diplomatic relations with North Korea” and that Korean schools in Japan should be eligible for state support.83 Since 2012, protests have been organized at the monument, criticizing its inscriptions as “anti-Japanese” and “fake” (detarame) and calling for its demolition. Playing on anti-Korean sentiments, the protestors claimed that some of the Koreans had come to Japan voluntarily and were only interested in financial gain. Dusting off the stereotype of “the criminal foreigner,” they further claimed that some foreign laborers who had escaped their work sites were later arrested by the police. While the historical record does not allow for a detailed reconstruction of individual cases, there were police arrests of fleeing Korean laborers. In some cases, the reason for the arrest was the charge of lese-majesty (fukei), a “crime” that Japanese officials could easily pin on a Korean fugitive.

In September 2013, the opponents of the memorial submitted a complaint to Gunma Prefecture, attempting to prevent the extension of permission for the monument and demanding its removal.84 The complaint stated that the prefecture’s approval would be a violation of the Local Autonomy Act (Chihō jichi-hō), on the grounds that “the inscriptions on the memorial are, in their entirety, falsehoods (kyogi), and thus are a flagrant violation of public welfare” as well as “a gross violation (shingai) of the sense of honor (meiyo kanjō) held by the citizens of the prefecture.” The complaint also referred to the discussion about the legality of Japanese rule in Korea mentioned above, claiming that “the Japanese annexation of Korea was concluded legally and was recognized by the League of Nations,” and adding that while Korea was “the poorest country in the world at the time of annexation,” Japanese support and investment brought “35 years of remarkable economic development” and resulted in “a massive improvement in Koreans’ livelihoods.” Wartime Korean laborers, the complainants argued, mostly came to Japan under their own steam, and the few instances of recruitments followed legal procedure. (Here, the complainants referred to the 1959 report by the Japanese government, cited above, claiming that among Korean residents of Japan at the time, only 245 Korean laborers had been conscripted and relocated to Japan.) Thus, they argued, it was unreasonable to make the citizens of Gunma apologize for and reflect on a past that never happened. The complaint also touched on administrative issues, claiming that it was illegal to waive the fees that are normally levied for private use of a public park, as had happened in the case of the memorial.85 Lastly, exposing a strongly xenophobic and anti-Korean attitude, the complainants claimed that, in principle, the law bans foreigners from the permanent use of public space without special permission from the Governor and that the Immigration Law bans foreigners from engaging in political activity, thus rendering the monument illegal.86 This claim was based on the (erroneous) assumption that the building of the monument had been initiated and organized by “Koreans.”

In December 2013, the prefectural administration published a detailed response in the Gunma Prefecture Bulletin (Gunma kenpō).87 It rebuts all the claims made by the memorial’s opponents, meticulously citing the relevant laws and administrative rules. The report emphasizes that, apart from their role as recreational spaces, parks are also sites of education (kyōyō), judging the monument as falling into this category. While there might be different views of the educational content presented, the presence of the memorial does not prejudice the use of the park as a recreational area. Using somewhat circular logic, the prefecture countered the claim that the inscription of the memorial presents “falsehoods” by drily stating: “The administration’s investigation took into consideration the contents of the memorial and eventually gave its approval. Thus, the contents of the memorial are not in conflict with the conditions for approval.”88 Regarding the claim that fees should not have been waived in this case, the administration explained that the decision was taken in accordance with the park’s function as a “public site” serving “the public interest.” The prefecture added that, had they been applied, the fees liable would have amounted to the—miniscule—sum of 5,740 Yen per year.89 Lastly, regarding the claim that the monument was illegal because it had been planned and erected by “foreigners,” the prefectural administration simply replied that the applicant (shinseisha) was Japanese. Though some Japanese of Korean descent might have been involved in the planning, they held Japanese nationality and thus their “ethnicity” (not an official category in Japanese law) was legally irrelevant.

Notwithstanding the administration’s rejection of the claims made by the opponents of the memorial, by early 2014 the issue had become highly politicized and attracted national attention (see next section). The pressure on local politicians—many of whom, in contrast to the early 2000s, had links with the ultranationalist group Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference)90—mounted by the day. In May 2014, right-wing members of the LDP submitted a petition to the Prefectural Assembly, demanding that permission for the monument be revoked. The Assembly, which had voted unanimously in support of the memorial in 2001, now voted to deny an extension of its approval.

Following this vote, the prefecture did an about-face. While the administrative section in charge of parks had concluded that no formal rules had been violated, the governor’s office ordered a further investigation. As a result, the prefecture overturned its earlier rejection of the case made by right-wing objectors and demanded that the Mamoru-kai demolish the memorial. Its logic largely followed the argument presented by the right-wing Do Better Japan! National Activities Committee. The main argument was that the ceremonies held at the monument were in violation of the conditions set out by the administration. Although the prefecture had never once raised an objection about the use of the memorial site or the ceremonies held there during the preceding ten years, in 2014 it argued that political statements had indeed been made during these ceremonies and that these were in violation of the conditions stipulated. More than ten years after it had been held, the prefecture even claimed that the inauguration ceremony (jomakushiki) in April 2004 had been “a political event” (seijiteki gyōji), on the grounds that some of the speeches had criticized postwar Japan’s lack of remorse for forced labor and wartime aggression as a reason for Japan’s isolation in East Asia.91 Being made in a “recreational park,” these statements—as well as the resulting protests by the right, which protested using noisy loudspeaker trucks in the 2010s—infringed on the rights of citizens seeking to use the park for recreational purposes.92 The prefecture’s line of argument implied that if objectors target a structure with sufficiently violent or noisy protests, as the right-wing protestors in Gunma did, it will be closed or removed from the public sphere, on the grounds that such disturbances impair its public function—in this case as a recreational space.

The prefecture’s decision is problematic in many ways.93 Most importantly, it immensely complicates the use of public spaces for representations of historical memory, even though spaces such as parks are the most common location for monuments and memorials. The great majority of Japanese statues of historical figures, for example, are located in public parks.94 The prefecture’s logic suggests that if a sufficient number of noisy or violent protests are held opposing a given statue, it must be taken down.

In November 2014, the Mamoru-kai, which had taken on the task of maintaining and administering the monument, took Gunma Prefecture to court. It won the first lawsuit when in 2018 Maebashi District Court ruled the prefecture’s decision “illegal” and an overstepping of its authority (sairyōken o itsudatsu).95 The court also asserted that citizens had not been prevented from using the park as a recreational site, because—as the evidence showed—until 2011, not a single complaint had been recorded.96 Given that the prefecture had never voiced any doubt that the inscription, or any part of it, had been “fake history,” the judge concluded, the onus would have been on the prefecture to inform protestors and their organizations that it considered the memorial inscription to be accurate rather than simply giving in to—clearly unfounded—protests. He also admonished the prefecture for failing to investigate violent incidents instigated by the opponents of the memorial, including fistfights with park employees and the police, instead focusing on how the peaceful ceremonies held at the memorial could have disturbed public order in the park.97

However, this ruling was overturned by the Tokyo High Court on 26 August 2021. In its ruling, the Tokyo High Court closely followed the train of logic employed by Gunma Prefecture. The Supreme Court, which had considered restrictions on the use of public parks problematic regarding freedom of expression in previous cases, in 2022 confirmed the ruling of the Tokyo High Court and chose not to accept (juri) the Mamoru-kai’s request for a further round of hearings.98

The supporters of the monument announced they would not comply with an order to demolish the monument, leaving its fate open for the time being.99 After the first lawsuit, the prefectural government requested the Mamoru-kai to either move the monument to a different location or purchase the part of the park in which it is located, thus converting it into private property.100 Although Gunma Governor Yamamoto Ichita welcomed the Supreme Court ruling, it seems unlikely that the prefecture is going to order the monument to be pulled down anytime soon. This kind of “cleansing” of Japan’s public spaces of critical and reflective approaches to the country’s wartime past would be seized on by the media and spark international outcry, undermining Japan’s international reputation.

Spillover Effects

The Supreme Court decision shows that critical interpretations of Japan’s wartime history, which are commonplace in academic circles, face an uphill battle in the public sphere. Beyond the debates in Gunma discussed here, there has been a spillover affecting other Japanese prefectures and cities, as well as national politics. This has occurred partly as a result of the support that historical revisionism has received from the government of Abe Shinzō, one of the central figures in the revisionist movement and prime minister of Japan from 2012 to 2020, exacerbated by the resulting media attention.101 While Abe’s focus was the “comfort women” issue (forced prostitution in wartime Japan and its dependencies), this has always been linked to the controversy over “forced labor” in the domestic debates about Japan’s wartime record. Both topics hardly rated a mention in parliamentary discussions before 1990. The following decade, however, brought frequent controversies, often focusing on terminology.102 Reacting to government apologies over the comfort women and other wartime injustices, conservative politicians insisted that “forced labor” and “forced relocation” were misleading terms that should be avoided. After a period of silence on the issue, the debate re-emerged in 2006/2007—during Abe’s first term as prime minister. Following another period of relative silence, the issue resurfaced in 2012, after Abe had assumed office for a second time. In 2014, the year in which the controversy in Gunma reached its peak, discussions of the comfort women and forced labor in the Diet also soared to record levels, according to the minutes of the National Diet. Apart from Abe’s LDP, the Japan Restoration Party also has frequently addressed these issues. As recently as 2021, Diet Member Baba Nobuyuki demanded a clarification of the term “forced labor” from the government, arguing that it is inappropriate to subsume all Koreans coming to Japan before and during the war under this label.103 Unsurprisingly, the government replied that neither wartime labor recruitment (boshū) nor conscription (chōyō) fall under what international treaties define as “forced labor.”104

The same line of argument was followed by a number of media outlets. In what would become an infamous “Editor’s Note,” in 2018 the country’s leading English-language newspaper, the Japan Times, declared that “the term ‘forced labor’ has been used to refer to laborers who were recruited before and during World War II to work for Japanese companies. However, because the conditions they worked under or how these workers were recruited varied, we will henceforth refer to them as ‘wartime laborers’.”105 In 2020, the paper confirmed that “after rigorous internal discussion, The Japan Times editorial leadership unanimously agreed to … maintain our description of ‘wartime labor’,” explaining that the various categories of boshū, kan assen, and chōyō cannot be summarized under the term “forced labor.”106

Right-wing media has played an even more active role in the campaign to erase critical approaches to Japan’s wartime past from public representation. Feeling empowered by the return of Abe as prime minister in 2012, conservative media launched an intensive campaign against the Gunma memorial—soon to be followed by other targets. At the height of discussions in Gunma, in 2014, the rightwing daily Sankei Shinbun launched a special column titled “History Wars” (rekishisen), bringing the Gunma affair and related controversies to national attention.107 Until then, the term rekishisen had been rarely used in Japanese coverage of historical issues. The Sankei may have adopted it from similar discussions taking place in Britain, when historians such as Richard Evans had criticized Education Minister Michael Gove (2010–14) for fighting a “history war. ”108 The coverage by Sankei, but also by ultra-rightwing internet channel Sakura TV, not only heaped additional pressure on the politicians charged with deciding the fate of the Gunma monument, but also resulted in similar attacks against monuments referring to forced labor in other parts of Japan, including Nagano, Fukuoka, Nara, and Osaka prefectures. All of these attacks occurred in 2014, the year in which the debates in Gunma were reaching a climax.

In Nagano, the prefectural government ordered references to Korean “forced labor” to be erased from information boards at the Matsushiro Underground Imperial Headquarters, constructed in the final months of the war as a refuge for the Emperor, should the Allies invade the Japanese mainland. It is estimated that up to 10,000 Koreans were assigned to work on this giant bunker, of whom at least 1,000 died during construction.109

In the city of Iizuka, Fukuoka Prefecture, a local group began campaigning for the removal of a “consolation” memorial dedicated to Koreans who died in this region of Japan during the war. According to the activists, the memorial, located in Iizuka Cemetery, was being used “politically.”110 The memorial stands next to an ossuary containing the remains of Koreans who died here during the war, leaving no doubt as to the reality of conscript labor, at least in this region of Japan. Objections focused on the inscription next to the memorial, which refers to “forced labor” and Japan’s war responsibility—statements the opponents of the memorial consider “political.” As in Gunma, the memorial was intended to foster reconciliation with Japan’s neighbors. To make this objective crystal clear, the city had named the part of the cemetery where the memorial was built “International Exchange Square” (Kokusai Kōryū Hiroba). The opponents of the memorial, however, were supported by some city councilors, who challenged the city’s stance on the issue at council meetings.111 The issue is yet to be resolved.

By contrast, in Tenri City, Nara Prefecture, in 2014 the city decided to remove a plaque referring to the use of “forced laborers” during the wartime construction of Yanagimoto Airfield. The 80cm x 1m steel plaque had been installed in 1995, at the height of Japan’s reconciliation efforts, when denialism regarding war crimes was on the decline in the political sphere and when the prime minister, Murayama Tomiichi, had issued an apology for Japan’s wartime conduct which received broad approval throughout East and Southeast Asia.112 In addition to forced labor, the Tenri marker also mentioned comfort women—always a very sensitive issue and one that historical revisionists are particularly concerned to erase from public memory.

Lastly, in Suita City, Osaka Prefecture, again in 2014, Mayor Kimoto Yasuhira decided that information displays in the city referring to “forced labor” should be revised or removed, given that the term was “misleading.” In a letter to prefectural governor Matsui Ichirō, he sought permission to do so, which the governor was pleased to grant. A member of the neoliberal-nationalist Restoration Party, Matsui is a strong supporter of historical revisionism, as was his predecessor as governor, Hashimoto Tōru, the politician who pressured the museum “Peace Osaka” to redesign its exhibitions to better reflect his own nationalist approach and remove displays critical of the wartime Japanese government.113

As in the case of Osaka, politicians took the lead in promoting historical revisionism across various municipalities and prefectures. Perhaps second only to prime minister Abe Shinzō in political prominence, the Governor of Tokyo Prefecture, Koike Yuriko (in office since 2016), has been active in supporting the movement. Until 2017, the governors of Tokyo had routinely sent a letter of condolence to the annual ceremony commemorating the massacre of more than 6,000 Koreans living in the greater Tokyo region following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Even Governor Ishihara Shintarō, a fervent nationalist, followed this practice during his long term in office (1999 to 2012). In 2017, however, Koike announced that she was “unwilling to privilege one victim group over another.” She also expressed doubts over the number of Koreans killed in the pogrom—a typical revisionist tactic—as if a slightly lower death toll would render the slaughter less heinous.114

These developments have also spilled over to affect the world of art, where the question of how to express historical issues has become increasingly contested. While artworks dealing with the “comfort women” issue stand at the center of these debates,115 works addressing the historical reality of forced labor have also sparked controversy. For example, when in 2017 the Gunma Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, located in the same park as the monument discussed above, planned to display an installation titled “Gunma Prefecture Consolation Memorial to Korean Mobilized Laborers” (Gunma-ken Chōsenjin Kyōsei Renkō Tsuitōhi) by Shirakawa Yoshio, it was attacked by local conservative groups. Although the installation was a “re-enactment in cloth” of the monument in the park, the museum had to remove the piece before the exhibition opened.116 Disinclined to get involved in the ongoing lawsuit about the original monument, and attract the ire of ultranationalists, the museum got cold feet. One of the official reasons given for cancelling the installation was that the piece “lacked neutrality.” The artist, Shirakawa Yoshio, commented that although he agreed with the museum that opinions on a particular piece of art can be varied and divisive, the decision to remove his creative work from the exhibit was not only a violation of the artist’s freedom of expression, guaranteed in the Japanese Constitution, but also a one-sided decision that totally disregards those in favor of its inclusion. The museum’s refusal to exhibit a particular piece because it (allegedly) “lacks neutrality” is itself an entirely one-sided judgment lacking neutrality. “Who,” Shirakawa asks, “decides which pieces of art are neutral?”117

The proponents of historical revisionism are becoming increasingly aggressive in their tactics, bullying local administrations into denying permission for monuments commemorating victims of war and colonial violence and intimidating museums into omitting controversial items or revising exhibitions. While this strategy has been particularly effective where historical revisionists have assumed positions of power—for example, in Osaka during Hashimoto Tōru’s term as mayor from 2011 to 2015—it has also affected the environment surrounding the mounting of history exhibitions throughout Japan. Even institutions that helped lay the foundations of post-war Japanese pacifism—such as the museums dedicated to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki or the memorials and museums commemorating the Battle of Okinawa in 1945—have come under attack and have been forced to adjust their narratives so as to be less “critical” of Japan’s wartime conduct.

Furthermore, in contrast to global trends (prior to the Covid-19 pandemic), the number of visitors to historical museums in Japan has been declining. While, for example, the Holocaust Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau in Oświęcim, Poland, had record numbers of visitors in 2019 (2.3 million), those visiting Japanese history museums—with the exception of the famous institutions commemorating the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki—have fallen steadily over the last few decades despite the pre-pandemic massive surge in tourism from overseas.118 This trend will certainly have long-term consequences for how Japan’s shared past with Asia is commemorated and remembered in Japan.

Concluding Remarks

Governments and civic groups all over the world have installed a growing number of memorials reminding citizens of the dark chapters in the nation’s past, often focusing on the victimization of (ethnic or political) minorities and oppressed colonial populations. In recent years, intense debates have emerged in Spain about its civil war in the 1930s, in Italy about the country’s colonial past, and in the United States and elsewhere over the history of slavery—not to mention the comfort women issue which has become a global issue in recent decades.119 On the other hand, memorials and statues built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and dedicated to historical figures implicated in the history of slavery and racial discrimination have been subjected to increasing scrutiny in recent years. Some American cities have removed such statues.120 The Black Lives Matter movement has invigorated the global movement which aims to challenge uncritical, nineteenth-century styles of representation of racism and colonialism in the public sphere. Few countries remained unaffected. Most recently, the king of Belgium issued an apology for his country’s colonial exploitation of Congo, an issue long avoided by both the royal family and the national government.121

These developments, however, have also prompted the rise—or resurgence—of historical revisionism across the globe. Revisionists regularly criticize historians for “exaggerating” the dark chapters of the nation’s past. They form links with politicians who feel uneasy about a perceived decline in national pride, leading to changes in history curricula in schools and public representations of history. Seeking to protect monuments that represent nineteenth century cultural and political values of colonialism, slavery, and patriarchy, these revisionists present “alternative facts,” seek to discredit the findings of academic research, and attack those promoting alternative monuments that take the victims’ perspective and call out perpetrators in the public sphere. When it comes to history education, as British historian Richard Evans has repeatedly reminded us, politicians frequently accuse historians of “trashing our past” and demand that pupils should study national history “in a connected narrative based on the rote-learning of names and dates, particularly those of kings and queens and battles and wars.”122

Gunma’s demolition men—and they are almost exclusively men—and the politicians in the prefectural assembly who support them, as well as the prefectural administrators who were so ready to do a volte-face, clearly fall into this category of historical revisionists. While no academic historian is involved in the campaign against the memorial in Takasaki City, its opponents receive strong support from politicians at both the local and national level, enabling the issue to gain national prominence and spilling over into other prefectures. On several occasions, Abe Shinzō adopted the talking points of those arguing that labor mobilization during the war did not exactly constitute forced labor. With reference to the comfort women, he publicly stated, as early as 2007, that in most cases recruitment was “not forcible in the narrow sense of the word,” begging the question of what might constitute a “narrow” definition of the term and what exactly might fall under “forcible” in the broader sense.123 During his second term as prime minister (2012–20), Abe initiated an investigation into the forced recruitment of comfort women, also highlighting the issue of forced labor in general. His aggressive attitude toward these issues emboldened historical revisionists across the country. Media coverage by right-wing outlets such as Sankei Shinbun, Sakura TV, the journals Hanada and WiLL (to which both Abe and his wife Akie frequently contributed articles),124 further accelerated the trend towards revision—or demolition—of critical representations of the nation’s wartime history in Japan’s public sphere.

Since Abe resigned in 2020, successive cabinets have voiced their concern that Japan needs to become a more responsible actor in international relations. Given that politicians and local administrations across the nation have endorsed moves to reject responsibility for Japan’s wartime past, this looks set to be a highly controversial objective, with some serious built-in contradictions. Nevertheless, Japan has announced its intention to strengthen cooperation not only with the US, but also with European nations, several of which have declared a renewed interest in the “Indo-Pacific Region,” a concept corresponding to Japan’s notion of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.” It is conspicuous how little attention is given to Korea and China in the framing of these geopolitical visions—both major actors in the region. Although more detrimental to Japanese–Korean relations than to the Sino-Japanese relationship at this point, Japan’s lack of progress in coming to terms with its wartime past explains why Tokyo does not consider closer relations with its two closest neighbors a realistic agenda. The demolition of memorials dedicated to the victims of the war in East Asia is hardly a step in the right direction.

Notes

“Chōsenjin Tsuitōhi. Saikōsai, Jōkoku Juri Sezu Gyakuten Haiso ga Kakunin,” Mainichi Shinbun, 18 June 2022.

See Sven Saaler, “Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 14, Issue 20, No.7 (15 October 2016) (Article ID 4966); Sven Saaler, “Heisei Historiography. Academic History and Public Commemoration in Japan, 1990–2020,” in Japan in the Heisei Era (1989–2019) Multidisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Noriko Murai, Jeff Kingston, and Tina Burrett (London and New York: Routledge, 2022).

See Sven Saaler, “Bad War or Good War? History and Politics in Post-war Japan,” in Critical Issues in Contemporary Japan, ed. Jeff Kingston (London and New York: Routledge, 2014); Sven Saaler, “Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan,” in Asian Nationalisms Reconsidered, ed. Jeff Kingston (London and New York: Routledge).

Hatano Sumio, ‘Chōyōkō’ Mondai to wa Nani ka: Chōsenjin Rōmudōin no Jittai to Nikkan Tairitsu (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 2020), 66.

Hiromichi Moteki, “The US, not Japan, was the Aggressor,” Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact; Toshio Tamogami, “Was Japan an Aggressor Nation?”; for an analysis of these developments see Saaler, “Nationalism and History.”

Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has joined this campaign—despite the fact that the whitewashing of Japan’s role in the war does nothing to improve the nation’s international reputation. See Sven Saaler, “Japan’s Soft Power and the ‘History Problem’,” in Remembrance—Responsibility—Reconciliation, ed. Lothar Wigger and Marie Dirnberger (Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer / J.B. Metzler, 2022).

In the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia), for example, between four and ten million people were recruited during the war as rōmusha—conscript labor during the Japanese occupation (1942-1945) – a term still used in Indonesia today. Mass conscription in the archipelago resulted in millions of deaths—Indonesia ranks among the East Asian nations having the highest death tolls during the war. This figure includes workers who died due to harsh labor conditions, disease, and starvation—caused by the Japanese re-allocation of the labor force from food cultivation to activities such as mining, and forced rice deliveries to feed the occupying forces. See Paul H. Kratoska, Asian Labor in the Wartime Japanese Empire: Unknown Histories (New York: Routledge, 2005); Shigeru Sato, War, Nationalism and Peasants: Java Under the Japanese Occupation. New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1996.

Tonomura, Chōsenjin, ch. 1; Hatano, ‘Chōyōkō’, 50. The original plan can be accessed in the online archive JACAR under the reference number A03023603200: Naikaku Shoki Kanchō, ed., Shōwa Jūyon-nendo Rōmu Dōin Jishi Keikaku Kōryō Ni-kan Suru-ken, 1939.

On the forced recruitment of comfort women and related questions of definition, see Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’: It’s Time for the Truth (in the Ordinary, Everyday Sense of the Word),” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 5, Issue 3 (1 March 2007) (Article ID 2373).

Unno Fukuju, “Chōsen no Rōmu Dōin,” in Kindai Nihon to Shokuminchi. Bōchō Suru Teikoku no Jin-ryū 5, ed. Ōe Shinobu et al. (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1993), 117-122; Tonomura, Chōsenjin, 209-211; Tonomura estimates that at least 700,000 Koreans were recruited for relocation to Japan through government-approved avenues of labor recruitment.

Rudolph J. Rummel, “Statistics of Japanese Democide. Estimates, Calculations, and Sources,” in Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900 (Charlottesville, Virginia: Center for National Security Law, School of Law, University of Virginia, 1997), available online.

On the dynamics of repatriation, see Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Guarding the Borders of Japan: Occupation, Korean War and Frontier Controls,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 9, Issue 8, No. 3 (21 February 2011) (Article ID 3490); and Jonathan Bull and Steven Ivings, “Investigating the Ukishima-maru Incident in Occupied Japan: Survivor Testimonies and Related Documents,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 19, Issue 19, No. 2 (1 October 2021) (Article ID 5638).

“No. 8471. Japan and Republic of Korea. Treaty on Basic Relations. Signed at Tokyo, on 22 June 1965,” registered 15 December 1966, United Nations Treaty Series Vol. 583 (New York: United Nations, 1968): 33-49.

“Agreement Between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation,” Wikisource, last modified March 23, 2022.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Failure of the Republic of Korea to Comply with Obligations Regarding Arbitration under the Agreement on the Settlement of Problem Concerning Property and Claims and on Economic Co-operation Between Japan and the Republic of Korea (Statement by Foreign Minister Taro Kono),” press release (19 July 2019).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “What Are the Facts Regarding Former Civilian Workers From the Korean Peninsula?,” fact sheet (19 November 2020). The Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued its own fact sheet, “FACTS REGARDING THE ISSUE OF FORCED LABOR.”

Hyonhee Shin, “South Korea Court Dismisses Forced Labor Case Against Japanese Firms,” Reuters, 7 June 2021.

Timothy Webster, “The Price of Settlement: World War II Reparations in China, Japan and Korea” New York University Journal of International Law and Politics (JILP), Vol. 51, No. 301, 2019.

See William Underwood, “Chinese Forced Labor, the Japanese Government and the Prospects for Redress,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 3, Issue 7 (6 July 2005) (Article ID 1693).

“Nishimatsu Lawsuit (Re World War II Forced Labour),” Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, 1 January 1998.

“Monument for Chinese Forced Laborers Unveiled in Hiroshima,” Deccan Herald, updated 3 May 2018; Takafumi Hatayama, “Relatives of Chinese Forced Laborers Visit Hiroshima to Attend Memorial Service,” The Chugoku Shimbun, 23 October 2013.

Ho-chul Sung, “Mitsubishi Built Memorial for Chinese Forced Labor Victims,” The Chosunilbo, 6 July 2022.

Totsuka Etsurō, “Japan’s Colonization of Korea in Light of International Law,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 9, Issue 9, No. 1 (28 February 2011) (Article ID 3493).

On UNESCO World Heritage politics, see Christoph Brumann, The Best We Share: Nation, Culture and World-Making in the UNESCO World Heritage Arena (New York: Berghahn Books, 2021).

“Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. Iron & Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining Inscribed on the World Heritage List,” Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.

See David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

On the significance of castles in post-1868 Japan, see Oleg Benesch and Ran Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Some commentators have noted that Yoshida should also be remembered as a pioneer of the ideology of foreign expansion; see Yasunori Takazane, “Should ‘Gunkanjima’ Be a World Heritage Site? – The Forgotten Scars of Korean Forced Labor,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 13, Issue 28, No. 1 (13 July 2015) (Article ID 4340).

David Palmer, “Gunkanjima / Battleship Island, Nagasaki: World Heritage Historical Site or Urban Ruins Tourist Attraction?,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 16, Issue 1, no. 4 (1 January 2018) (Article ID 5102).

David Palmer, “Japan’s World Heritage Miike Coal Mine – Where Prisoners-of-War Worked ‘Like Slaves’,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 19, Issue 13, No. 1 (1 July 2021) (Article ID 5605).

Nick Kapur, Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

“Japan Explanation of Korean Wartime Forced Labor Insufficient: UNESCO,” Kyodo News, 22 July 2021.

For details, see Nikolai Johnsen, “Katō Kōko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution – Forgetting Forced Labor to Celebrate Japan’s World Heritage Sites, Part 1”, The Asia Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 19, Issue 23, No. 1 (1 December 2021) (Article ID 5652); Nikolai Johnsen, “Katō Kōko’s Meiji Industrial Revolution – Forgetting Forced Labor to Celebrate Japan’s World Heritage Sites, Part 2,” The Asia Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 19, Issue 24, No. 5 (15 December 2021) (Article ID 5663).

See Nikolai Johnsen, “The Sado Gold Mine and Japan’s ‘History War’ Versus the Memory of Korean Forced Laborers,” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus, Vol. 20, Issue 5, No. 1 (1 March 2022) (Article ID 5686); Justin McCurry, “Japan and South Korea in Row Over Mines That Used Forced Labour,” The Guardian, 19 February 2020.