Abstract

In April 2015, Peace Osaka, a publicly-funded museum famous for its hard-hitting exhibits about Japan’s wars of the 1930s and 1940s, reopened after a “renewal”. In the new exhibits, discussion of Japanese aggression and atrocities has been completely removed and the stance of the museum has changed from progressive to conservative. Based on a photographic record of the pre- and post-“renewal” exhibits, this essay discusses in what ways and why Peace Osaka has changed under three headings: physical conversion, mission conversion and ideological conversion. The process of conversion started with nationalist campaigns to revise and undermine the exhibits during the 1990s and was ultimately realized under conservative local governments in the 2010s. The conversion is not simply a sign of the recent “shift to the right” in Japanese politics under the administration of Abe Shinzō. Instead, it reveals a longer-term issue of nationalist assaults on the narratives in local peace museums and the vulnerabilities of progressive official narratives.

Introduction

On 30 April 2015, the Osaka International Peace Center (Peace Osaka)1 reopened after its “renewal” (rinyūaru). After opening in 1991, Peace Osaka became known as one of Japan’s most forthright museums, certainly the most forthright publicly-funded museum, examining Japanese wartime aggression and atrocities. However, in 2011, the Ishin no Kai (Japan Restoration Party) led by Hashimoto Tōru took control of both the prefectural and municipal assemblies in Osaka. Hashimoto’s conservative credentials regarding war history became world news in 2013 and 2014 when his controversial comments about the “comfort women” precipitated a storm of international protest.2 But well before then, Hashimoto and the Japan Restoration Party had launched a budgetary and administrative assault on Peace Osaka and another progressive museum in the city, Osaka Human Rights Museum (Liberty Osaka).3 Under direct threat of closure from Hashimoto and his party if its exhibits continued to be “inappropriate”, Peace Osaka embarked on the first major overhaul of its exhibits since opening a quarter of a century earlier. The museum closed on 1 September 2014, its old exhibits were discarded, and the museum reopened with new exhibits on 30 April 2015.

|

Figure 1: Peace Osaka (May 2013) |

“Renewal” seems an inappropriate term to describe the transformation. On the outside it is the same museum: the name, the logo and the building remain (Figure 1). But on the inside – in terms of its layout, target audience and core message – the “renewed” Peace Osaka has changed fundamentally from the old Peace Osaka. The old exhibits were progressive. They depicted Japanese wartime aggression and forced visitors to reconcile this history with the museum’s other main narrative: the air raids that destroyed Osaka in 1945. The new exhibits, by contrast, largely elide Japan’s war with China and Asia and center on the devastation of the Osaka air raids. They are conservative in the sense of avoiding any categorization of Japan’s wars as “aggressive” though recognizing the existence of some “aggressive acts” (namely atrocities). Japanese nationalists – defined as those who present an affirmative narrative of Japan’s wars and deny by omission Japanese war crimes (most notably the Nanjing atrocity of 1937) – led the attack on Peace Osaka’s old exhibits and their influence and rhetoric are also evident in the new exhibits on occasions.5 The ideological change goes beyond removing graphic exhibits of Japanese atrocities. The entire lexicon of the museum has been aligned with archetypal conservative rhetoric. This ideological “conversion” is far more significant than any cosmetic “renewal” in the appearance of the museum.

A Museum Under Attack

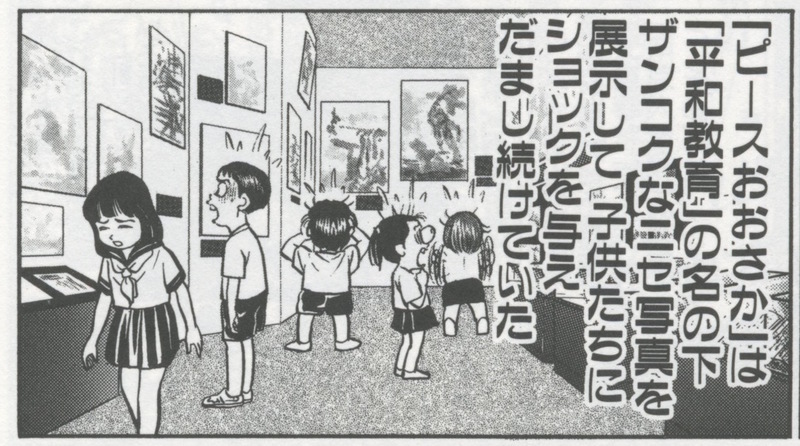

When it first opened, Peace Osaka’s progressive stance earned it many plaudits from international observers and it has received much coverage in the international literature on Japanese war memories.6 Domestically, the exhibits proved to be divisive, gaining plaudits from progressives but drawing criticisms from conservatives and nationalists. In 1996 Japanese nationalist activists began targeting Peace Osaka’s exhibits. In 1997, the Group to Correct the Biased Exhibits of War-Related Material was established and demanded changes to the exhibits. Peace Osaka removed one photo and changed the captions of two others where nationalist assertions of inaccuracy could not be refuted. There was a further set of revisions to the exhibits in 1998.7 Around the same time, nationalist manga artist Kobayashi Yoshinori joined the assault on the museum in his best-selling manga Sensōron (On War). “In the name of ‘peace education’,” he wrote, “Peace Osaka exhibits brutal, fabricated photos, and has shocked and tricked schoolchildren” (Figure 2). He accused the museum of “brainwashing” children and cited comments in visitors’ books from shocked youngsters as evidence of its pernicious influence.8

|

Figure 2: Kobayashi depicts children being shocked by the exhibits at Peace Osaka |

Kobayashi’s manga identifies one of the reasons nationalists took such issue with Peace Osaka: the museum has a key role as a site of school visits. The old Peace Osaka had over 1.7 million visitors from 1991 to its “renewal,”9 of whom school children (most of them on official school trips) comprised about 60 per cent.10 Nationalist attacks on Peace Osaka, therefore, overlapped with the broader movement in the 1990s spearheaded by the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashii Rekishi wo Tsukurukai) to correct “masochistic” history education.

In addition to demands to change the exhibits, a key nationalist tactic was to undermine the progressive credentials of Peace Osaka by requesting the use of Peace Osaka’s facilities for events promoting nationalist versions of history. As a publicly-funded museum, Peace Osaka could not turn down requests by local taxpayers to use their facilities on ideological grounds. In 1999 there was a public screening of the film Pride, Unmei no Toki, about the Tokyo Trials. This movie portrayed wartime leader and convicted Class A war criminal Tōjō Hideki in a sympathetic light and depicted the Tokyo Trials as kangaroo justice. A much more damaging event was on 23 January 2000 when a symposium titled “The Biggest Lie of the Twentieth Century: A Comprehensive Examination of the Nanjing Massacre” was held at the museum.11 The museum stated that it did not endorse the content of the symposium but it could not refuse to let the group behind the event use the museum’s facilities. The Peace Osaka Civic Network organized a protest against the symposium attended by 150 people and followed it up with a counter-symposium of their own.12 But the damage to Peace Osaka’s credibility was done. The museum was finding it increasingly difficult to ward off criticisms and attempts to undermine it. Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka have argued that the museum failed to mount an effective response, preferring instead to avoid controversy and to take a “defensive posture”.13

Ultimately, Peace Osaka’s Achilles Heel was its reliance on public funding from Osaka Prefecture and Osaka City. When politicians with conservative views on war history took power in both local governments, the museum became extremely vulnerable. This happened in two stages. First, Hashimoto Tōru was elected governor of Osaka Prefecture in 2008. He became mayor of Osaka City in 2011. He was succeeded as governor by his ally in the Japan Restoration Party, Matsui Ichirō, a former member of the LDP who is close personally and politically to Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide. From this point onwards, the simultaneous threats to cut funding from both the prefecture and city gained momentum. With revenues from entrance fees of only a few million yen per year (children under 15 enter for free so paying visitors only numbered a few tens of thousands, and adults only pay 250 yen), the museum was financially unsustainable without taxpayers’ money. Peace Osaka had three options: 1) surrender to the demands for a change in stance, 2) close down, and 3) refuse to change its stance and continue operations as a private organization.

The third option was taken by Liberty Osaka, a museum focusing on human rights issues that had also been targeted by the Japan Restoration Party. In 2008, Hashimoto had criticized this museum for being “negative”, saying that it “did not give children dreams and hopes”. Not even attempting to conceal that a change of stance was a prerequisite for continued funding, in 2012 Hashimoto commented: “We gave them a chance (to change the exhibits), but they did not take it. We will resolve the issue this year”.14 Liberty Osaka lost all public funding in 2013 and started its new life as a private museum. Osaka City launched proceedings against Liberty Osaka in February 2015 to evict them from the building and take back the city-owned land when Liberty Osaka refused to (read also “could not”) pay the rent.15

Faced with the Japan Restoration Party’s determination to remove progressive narratives from public museums in Osaka, Peace Osaka took the first option of surrender. In 2013, a network of civic groups in the Kansai region called the Network to Consider the Peace Osaka Crisis (Pīsu Ōsaka no Kiki wo Kangaeru Renrakukai) was formed and they campaigned against the proposed renewal. They cited the fact that some of the victims of the Osaka air raids were Chinese forced laborers, so even the story of the air raids was intertwined with Japan’s aggression on the continent.16 However, their campaigns, which included holding meetings and online petitions, were in vain. Plans for the renewal were drawn up in 2012 and on 1 April 2013 the entire staff was replaced.17 Bids for the new exhibits were solicited and the museum closed its doors in September 2014 for the refurbishment.

When the renewal plans were announced, I took the precaution of compiling a complete photographic record of the old exhibits on a visit in May 2013. I revisited Peace Osaka in May 2015 to see how the exhibits had changed (for news reports on Japanese television that discuss the changes in the exhibit, see the two YouTube videos in the Appendix at the end of the essay). In the next three sections, I compare Peace Osaka pre- and post-“renewal” under three headings: physical conversion, the new look and layout of the exhibits; mission conversion, the new target audience at which the museum directs its message; and ideological conversion, Peace Osaka’s new stance on war history.

Physical Conversion

From the outside, Peace Osaka looks just the same. On the inside, there is little architectural change and the route that visitors take through the building has remained the same. However, the themes covered in each space within the museum have been reorganized. The pre- and post-“renewal” layouts can be compared by looking at the pamphlets (Download file of the old pamphlet, Download file of the new pamphlet). A summary is in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of the New and Old Exhibits at Peace Osaka

|

Floor |

1991-2014 Exhibits |

2015- Exhibits |

||

|

Room |

Contents |

Room |

Contents |

|

|

2 |

Exhibition Room A |

Osaka Air Raid and the Daily Life of the People |

Zone A |

In 1945, Osaka was Engulfed in Fire |

|

Zone B |

When the World was Embroiled in War |

|||

|

Zone C |

The Lives of Children During the War |

|||

|

1 |

Exhibition Room B |

15-Year War |

Zone D |

Osaka Reduced to Ashes, with Many Casualties |

|

Special Exhibition Room |

Special Exhibition Room |

|||

|

3 |

Exhibition Room C |

Aspiration for Peace |

Zone E |

Osaka Regains Its Vigor |

|

Zone F |

Ensuring a Peaceful Future |

|||

|

Video Area |

Video Area |

|||

|

Library |

Library |

|||

The key changes are as follows:

Air raid exhibits

The main air raid exhibits moved from the second to the first floor. In the new exhibits, Zone A “In 1945, Osaka Was Engulfed in Fire” only acts as a brief prologue. The air raids are now more “central” to the new exhibits and are one of two parts of the museum that were genuinely “renewed” (the other being the exhibits about life during the war in Osaka, discussed below). The story of the air raids hardly changed, although the presentation did change. Some items have been retained, such as the paintings by survivors or models of bomb casings. Overall the new exhibits use more up-to-date technology, such as greater use of audio-visual displays. There is a small testimony room in Zone D in which testimony plays on a television screen, whereas in the old exhibits the testimony was in books or on panels. On the wall of Zone D there is a model of the Ebisubashi area, which becomes the screen onto which a film about the raids is superimposed using projection mapping. There is also a new exhibit: a reconstruction of an air raid shelter that visitors can sit in.

The air raid exhibits could be “renewed” without basic change because, as a story of Japanese victimhood, the air raid narrative did not need to be “converted”. Air raids on Japan barely feature in the heated debates over Japanese war responsibility because responsibility issues relating to the bombing of Japanese cities rest primarily with the United States Air Force.18 For conservatives and nationalists seeking to downplay or expunge Japanese war guilt and counter “masochistic” versions of history, including instances of war crimes committed against Japanese is beneficial. Incendiary bombing targeting civilians was against all laws of war at the time and may be called an Allied war crime. Progressives and nationalists in Japan may have different motivations for focusing on the history of air raids (“the inherent atrocity of war” vs “examples of enemy criminality”), but as long as air raid narratives remain largely decontextualized from broader discussions about Japanese war responsibility, people of all ideological persuasions can discuss the raids using the common language of the suffering of Japan’s civilian population.

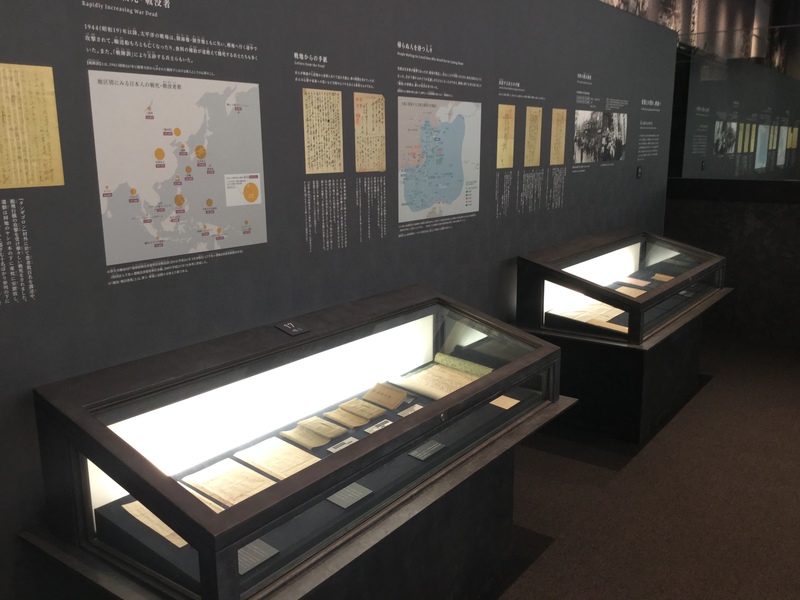

Historical Context

Zone B, “When the World Was Embroiled in War”, is where the greatest physical, mission and ideological conversions took place. The broader context of the war is explained in a video, a chronology (Figure 3), and wall exhibits about developing military technology. These replaced the exhibits in old Exhibition Room B, “15-Year War”, which contained many graphic images of war violence (Figure 4). The removal of Peace Osaka’s hard-hitting displays about Japanese aggression in Asia are the key to the museum’s ideological conversion, which is discussed fully in the second half of this essay.

|

|

| Figure 3: Zone B (new exhibits) | Figure 4: Exhibition Room B (old exhibits) |

Life During the War in Osaka

Zone C, “The Lives of Children During the War”, is in the same physical space formerly occupied by the second half of old Exhibition Room A “… the Daily Life of the People”. Like the section on air raids, this section was more “renewed” than “converted”. At the far end of the room (see Figures 5 and 6) there is a reconstruction of a house, which shows typical living conditions in Osaka before the raids. In the new exhibits a new type of display was introduced: touchscreen panels embedded into the top of a school desk (Figure 6). The new layout of this room resembling a classroom reflects the museum’s stated post-renewal mission (discussed in the next section), namely making children its main target audience.

|

|

| Figure 5: Exhibition Room A “… the Daily Life of the People” (old exhibits) | Figure 6: Zone C “The Lives of Children During the War” (new exhibits) |

Lessons from the Postwar Era

The exhibits on the third floor now have two main themes rather than one. In the old exhibits, Exhibition Room C “Aspiration for Peace” focused on nuclear issues and international diplomacy. Around the room were pictures of many of the key events of postwar world history and clocks around the walls alluded to the countdown to nuclear holocaust (see Figure 8 below). The new exhibits contain two sections. Zone E “Osaka Regains its Vigor” charts Osaka’s recovery in the postwar. Zone F “Ensuring a Peaceful Future”, eschews the grand stage of international politics and presents a more localized story of Japan’s contribution to the international community (such as ODA contributions) and the contributions that children can make to world peace via efforts such as environmental protection. This reflects Peace Osaka’s new mission to “place Osaka at the center”.

Others

The other facilities in Peace Osaka, such as its video viewing room, library, rest areas, special exhibition space and gardens underwent no significant changes.

Mission Conversion

The reorientation of the museum’s message to something deemed more appropriate for children on school visits was a key rationale for the “renewal”. The renewal plans called for the following: “‘Ōsaka chūshin’ ni ‘kodomo mesen’ de ‘heiwa wo jibun jishin no kadai to shite kangaerareru tenji’ ni rinyūaru” (A renewal which places Osaka at the center, uses a child’s perspective, and has exhibits that enable visitors to think of peace as a personal issue for them).19 The plans highlighted various ways in which the exhibits could be more child-friendly, divided into “hard” (physical) and “soft” (content). Proposed physical aspects of the renewal included placing panels at appropriate heights for children and having more exhibits that could be touched or experienced (such as a reconstruction of an air raid shelter). Proposed content aspects included using “concrete, concise expressions” that children could understand, providing educational materials, converting old language into modern Japanese, stimulating children to ask “what” and “why” questions, and staging events to encourage conversation and interaction among schoolchild visitors and their guides.20

These proposals reflected a reasonable goal to reorient the exhibits toward the museum’s main audience. Indeed, there was much scope to criticize the old exhibits regarding their suitability for school visits. I will return to the two main criticisms (the use of violent imagery and the difficulty level of the content) shortly, but first it is important to consider briefly the politics of criticizing the old Peace Osaka exhibits.

The criticisms of Peace Osaka by nationalists such as Kobayashi Yoshinori have already been mentioned (Figure 2), but there is also the issue of criticisms by progressives of the original exhibits. Referring to the old exhibits in Exhibition Room B “15-Year War”, Akiko Takenaka wrote:

Viewed in its entirety, the material exhibited here does not present a coherent narrative of the fifteen wartime years. Items associated with the war in China occupy a significant area in the room, but they do not clarify the reason the Japanese military was in China in the first place. Without a historical context, the impression given is that members of the Japanese military haphazardly committed atrocious acts in China, and in retaliation, Osaka residents were harmed. But since evaluation of this room has become so politicized, few who take the side of Peace Osaka on its understanding of the war have ventured to criticize the methodology.21

With Peace Osaka under concerted attack from nationalists, progressives feared fatally undermining the museum by adding their own criticisms to the debate. Peace Osaka’s significance as a rare example of a progressive publicly-funded museum made the museum worth defending in spite of its flaws. Few progressives writing in Japanese, therefore, ventured substantial criticisms.

However, the old Peace Osaka exhibits were open to criticism on grounds unrelated to historical consciousness. In addition to Takenaka’s criticisms regarding narrative coherence, two more criticisms of the old Peace Osaka exhibits can be made regarding its suitability for its primary audience (children on school trips).

|

Figure 7: Holocaust Exhibits (old exhibits, Exhibition Room B) |

The first criticism was the graphic nature of the old exhibits. There were many close-up photographs of dead bodies, and others depicted severely emaciated forced laborers in Asia or victims of the Nazi Holocaust in Europe (Figure 7). These were the images that Kobayashi Yoshinori took such exception to (see Figure 2), although his concern had more to do with the museum “brainwashing” children into hating Japan rather than the potential psychological damage caused through exposure to graphic images of war violence at a young age.22 Nevertheless, there is a legitimate debate to be had over the appropriateness of such explicit images of war violence in a museum that has children’s education as a primary function. The old Peace Osaka was clearly “R-rated”, so its conversion to something “PG-rated” addresses a genuine educational and ethical concern about exposing children to explicit imagery as part of their education.

The debate over the appropriate age to show graphic images of war violence to children is complex. There is a place and role for brutally explicit war exhibitions, and displaying images shocking enough to make even most adults recoil can be an effective strategy for conveying the message of peace. But such exhibitions should be places – either the museum as a whole or a clearly-marked section within a museum – into which consenting adults (and perhaps older teenagers, too) go of their own volition in the knowledge of what they will see.23 They are not places to which children should be taken without their own and explicit parental consent. This was an issue on which Kobayashi Yoshinori certainly had a point, whatever one thinks of his nationalist agenda.

|

Figure 8: Exhibition Room C “Aspiration for Peace” (old exhibits) |

The second set of grounds on which to criticize the old exhibits at Peace Osaka in the context of their role as a site of children’s education was the difficulty level of the old Exhibition Room C exhibits. “Difficulty level” refers to the amount of prior historical knowledge that was required to make sense of the exhibits. Figure 8 shows some of the panels in old Exhibition Room C “Aspiration for Peace”. There are many images of key events relating to war and peace from around the world in the postwar era. One of the photos visible is the famous image of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO leader Yasser Arafat shaking hands as President Clinton looks on. This photo is from 1993 and appreciating its significance requires considerable knowledge of Middle East affairs. Captions were provided, but many were quite long and placed high up on the wall beyond the eye line of children, a problem mentioned in the renewal plans. It all suggests an adult target audience rather than an elementary or junior high school one. Furthermore, mirroring the criticisms of Akiko Takenaka above relating to the incoherent nature of the “15-Year War” exhibitions, these exhibits too could be criticized for being just a montage of seemingly unrelated images having something to do with “peace”.

The conversion of Peace Osaka from adult-orientated exhibits to child-orientated exhibits, its “mission conversion”, therefore, was justifiable on various grounds. Mission conversion did not necessarily equate to ideological conversion. Mission conversion could have been approached as largely a matter of public accountability and as a reflection of a need to justify the use of limited public resources to sustain a museum that had little potential to sustain itself through entrance fees from the general public.

However, the renewal plans listed “three points for attention” (ryūiten) where mission conversion could and would overlap with ideological conversion.24

First, as a place where elementary, junior high and senior high school children would receive peace education, the exhibits should be broadly in accordance with the Fundamental Law of Education and New Educational Guidelines. In other words, the exhibits would be aligned with official national standards. On the one hand, this would promote consistency between the lessons children received by reading their government-approved school textbooks and by going on school trips to Peace Osaka. On the other hand, since the Fundamental Law of Education was revised in 2006 to include a clause on patriotism (aikokushin)25, this could also be interpreted as a sign that the new exhibits would be promoting “love of country” and not a “masochistic”, self-critical view.

Second, there would be sufficient checks into the sources of the information and effort to ensure the exhibits were “more appropriate” (yori tekisetsu). This is a veiled reference to the issues of “mislabeling” and “fake atrocity photographs” for which nationalists had long criticized the museum (resulting in some changes in 1997-1998 as described above). While removing any items of dubious historical accuracy cannot be criticized on historiographical grounds, this effectively gave a veto to nationalists on the contents of the new exhibits. A classic nationalist tactic for blocking or removing discussion of Japanese aggression from official accounts (whether government-screened textbooks, official histories or public museums) has been for nationalist historians to contest vigorously the reliability of evidence of atrocities (particularly photos, testimony and non-Japanese documents). Contested history then has to be removed from or referred to vaguely in official accounts on the grounds that “the facts cannot be determined by historians”. To incorporate disputed history in an official narrative would be “biased” and unacceptable. The result is that only what can be agreed upon across the ideological spectrum can be included as “fact”.26 Within this environment, all nationalists have to do is to protest vigorously the existence of massacres after the fall of Nanjing in 1937, for example, and the inclusion of clear statements saying the Nanjing Massacre occurred can be watered down, or even struck from the official account altogether, the latter being the case in the new museum exhibits.

The third point was that while the exhibits would “accurately convey the horrors of war”, “sensitive children” (kanjusei yutakana kodomo) would not be exposed to “excessive burdens” (kadaina futan). This was code that graphic images (particularly photographs) of war violence would be removed. As already argued, this case can be made on educational and child welfare grounds regardless of one’s ideological interpretation of Asia-Pacific War history. It is worth noting, however, that the museum visited by most schoolchildren, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, has graphic photos of dead bodies and arguments of child welfare have not been made with any significant force regarding those exhibits. Nevertheless, the decision to make the museum child-friendly meant that not only the photographs of Hiroshima and Holocaust victims would go, but also the photographs of atrocities committed by Japanese. The only graphic images of war violence in the renewed Peace Osaka are paintings by survivors of the Osaka air raids on the wall by the ramp connecting Zones C and D.

In summary, while the decision to convert Peace Osaka’s mission to the education of school children was justifiable given the high proportion of school children among the museum’s visitors, the new mission statement also proved to be an effective pretext for dismantling the exhibits of aggression that nationalists had long opposed. Placing “Osaka at the center” removed the need to give any details about the war’s effects on people elsewhere in Japan, let alone in Asia or beyond, and a “child’s perspective” made explicit imagery of war violence inappropriate, particularly any violence perpetrated by Japan which might contravene the Fundamental Law of Education’s stipulation to promote patriotism. The alibi had been created for the museum’s ideological conversion and with it the watering down of the powerful peace message.

Ideological Conversion

Lexicon and Exhibit Content

Terminology is an important signifier within Japanese war discourses. For example, terms such as Jūgōnen sensō (Fifteen-Year War, 1931-45) and Nankin (dai)gyakusatsu (Nanking (great) massacre) are preferred by progressive historians, while conservative or nationalist historians prefer Shina jihen (China Incident, 1937- ), Daitō sensō (Great East Asia War, 1941- ) and Nankin jiken (Nanking incident).27 Comparison of these signifiers in the pre- and post-“renewal” exhibits reveals an unambiguous shift in lexicon from progressive to conservative. In the old exhibits, the name of Exhibition Room B was “15-Year War”. This term has disappeared entirely from the new exhibits. So has the term “shinryaku”, aggression. In the chronology in Zone B of the new exhibits, there are references to the China Incident and Nanjing Incident, namely the conservative lexicon. The only use of the word “massacre” (gyakusatsu) that I could find in the new exhibits was in reference to the Rwandan genocide of 1994, which was mentioned in Zone F.

The change in usage of these signifiers is a subtle indication of a shift in stance. The more obvious indication is the change in the content of the exhibits relating to Japanese aggression. The old Peace Osaka’s acknowledgement of Japanese aggression and wartime atrocities was clear in Exhibition Room B “15-Year War”: the exhibits included panels about “comfort women” and forced labor (Figure 9), a Malaysian school textbook opened at a page which had a picture of Japanese soldiers impaling a baby on a bayonet (Figure 10), and various photos of the victims of Japanese atrocities (Figure 11). Not only was all this was removed, but also the new exhibits contain no explicit acknowledgements of any Japanese atrocities or responsibility.

Peace Osaka’s New “Grand Narrative”

In the new exhibits, historical context is given in a video in Zone B and the chronology in Zone C. Analysis of the video reveals Peace Osaka’s new ideology.28 I will focus on three particular themes: nineteenth century imperialism, Nanjing, and the Pacific War.

1) Nineteenth century imperialism – The video begins with the period just before the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and starts by asking the question, “Why did Japan wage war with the U.S.?” The following quotation is from the very beginning of the video:

To protect its independence from the major western powers that had undertaken the colonization of Asia, Japan adopted the policy of increasing wealth and military power after the Meiji Restoration. In the process of establishing national sovereignty and delimitation of its territory, Japan determined the territory of Korea as land it should protect against Russia, which was seeking to expand southward. Japan advanced into Korea, a territory over which the Qing dynasty asserted colonial power, and both struggled for power in the Sino-Japanese War that began in 1894. Japan won the war and acquired the Liaodong Peninsula and Taiwan along with a large amount of reparations. [italics added].29

The explosive outward thrust of Japanese imperialism from the Meiji era forward is cast as essentially defensive and as a response against western imperialism. Situating Japanese imperialism within the broader context of other nations’ imperialist behavior is important and in fundamental ways Japan was simply following the international norms of the era of imperialism. However, such arguments easily slip into justification via relativizing: “Japan only did what others did, so it’s OK”. Furthermore, to start the narrative in 1894-95 with the Sino-Japanese War (as many English-language accounts of Japanese imperialism do), ignores earlier examples of homegrown imperialism in the Ryukyu Kingdom (Okinawa) and Ezo (Hokkaido), which have been highlighted by both Japanese and international scholars.30 The video even slips into nationalistic self-justification when the “advance into” Korea is depicted as a benevolent act to “protect” it from Russia, which portrays Japanese imperialism as a force for good in contrast to Russian imperialism as a force for evil (although later on in the video “growing resistance” to Japanese rule is acknowledged).

2) Nanjing – The way in which a Japanese person or organization describes events prior to and after the fall of Nanjing in December 1937 is one of the quickest litmus tests of their historical consciousness. This is what the Peace Osaka video says (in its English subtitles):

In 1937, amid increasing hostilities between China and the Japanese Army as it attempted to take control of Northern China, the Chinese Army and the Japanese Army engaged in a battle at Lugouqiao (Marco Polo Bridge) in the suburbs of Beijing. Many Japanese soldiers and residents fell victim in Tongzhou and elsewhere. The war spread to Shanghai, initiating the full-scale undeclared Sino-Japanese War. Many residents were victimized by the Japanese Army in the Nanjing incident and the bombing of Chongqing.

This is a key section illustrative of Peace Osaka’s shift to conservatism. In the old exhibits, a panel “Invading the Asian Continent” had given more detail about Japan’s actions in China leading up to the Manchurian Incident (rather than alluding vaguely to “increasing hostilities”). A video below that panel stated that Japanese soldiers “occupied Nanjing on December 13, 1937 and massacred, it is said, tens or hundreds of thousands of Chinese people”. At this point on the screen pictures flashed of corpses in the streets of Nanjing. The narration about Nanjing in the new video, by contrast, uses the term “Nanjing incident” and takes place against the backdrop of a map indicating the locations of the Marco Polo Bridge, Tongzhou, Shanghai, Nanjing and Chongqing. While acknowledging “many” deaths in Nanjing and Chongqing, there are no death tolls given and no overt indications of an atrocity through the use of a term like “massacre”.

Another important signifier is the mention of Tongzhou in the new video. On 29 July 1937, just a few weeks after the Marco Polo Bridge incident, Japanese-trained Chinese troops of the East Hebei Army mutinied against their Japanese commanders and slaughtered around 260 Japanese including civilians. Inclusion of this incident in histories of the China War is de rigueur for Japanese nationalists because it is the key example of an atrocity committed by Chinese soldiers against Japanese civilians.31 In Peace Osaka’s video, Tongzhou is mentioned before Nanjing (chronologically correct but suggestive – “the Chinese did it first”) and the implied equivalence in scale is deeply misleading. In short, this mention of Tongzhou in the video indicates the influence of histories written by Nanjing Massacre deniers.

3) The Pacific War – The sections of the video about the Pacific War confirm the conclusion of a conservative narrative:

On December 8, 1941, the Japanese Army landed on the British Malay Peninsula in search of oil in the Dutch East Indies. At the same time it launched a surprise attack on the U.S. Navy base in Hawaii, thus starting the Pacific War. Through these events, the whole world became engulfed in war. Japan stated that the purpose of the war was self-defense and construction of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere as it occupied most of Southeast Asia in half a year. However, because food and resources were diverted and local residents were forced to cooperate with the war effort, armed anti-Japanese movements emerged. … Mobilization of [Japanese] university students began in 1943. Men not serving in the military were recruited and junior high school students and young women were also mobilized for labor. People in Korea and China were mobilized as well and forced to work under severe conditions [all italics added].

These sections provide no hint of an interpretation of Japan’s wars as “aggressive”. Instead, the wartime explanation that the war was in “self-defense” is cited. The many atrocities committed in the Pacific theater are ignored, and the harsh treatment of people in occupied territories is described using the oxymoronic and euphemistic term “forced to cooperate with”. There is an implied equivalence in labor mobilization for Japanese, Koreans and Chinese through the common use of the word “mobilization”, dōin. The (taboo for nationalists) term “forced labor”, kyōsei rōdō, is not used (the Japanese narration says hatarakesareta, “made to work”).

Regarding air raids – and bearing in mind that preserving memories of the raids is central to Peace Osaka’s new mission – the video explains:

From November 1944 onward, U.S. forces began full-scale air raids on Japanese military facilities and factories, and later, with the intention of breaking the fighting spirit of Japanese citizens and ending the war early, launched indiscriminate attacks. Tokyo, Osaka and other major cities were reduced to ashes and many residents lost their lives. Iwo Jima was occupied by U.S. forces in March 1945, followed by the main island of Okinawa in June, and many Japanese soldiers and civilians died cruel deaths. In July, the Potsdam Declaration demanding the unconditional surrender of Japan was announced by the United States, the United Kingdom and China, but Japan did not accept it in the hope of intervention by the Soviet Union. In order to end the war without delay and to avoid an invasion into Japan’s mainland that would inevitably cause substantial casualties on own side [sic], and to gain the upper hand over the Soviet Union after the war, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6 and on Nagasaki on August 9. In the meantime, based on a secret agreement made with the United States and the United Kingdom at the Yalta Conference in February, the Soviet Union violated the neutrality pact with Japan and joined the war against Japan. After August 9, the Soviet Union invaded Manchuria, Korea, South Sakhalin and Chishima. On August 14, Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration and on August 15, the Emperor informed the nation of its defeat [all italics added].

In contrast to the earlier sections in which very little emotive language was used, in this final section emotive terminology increases. The air raids are “indiscriminate attacks” (the Japanese raids on Chongqing were not described as such), Japanese soldiers and civilians die “cruel deaths” (rather than “becoming victims”), and we get the first use of the word “invasion” (as opposed to “advanced into”) when the Soviet Union “violates” the neutrality pact (whereas Pearl Harbor is a “surprise attack”). The final section of the video subtly leads the viewer toward an interpretation of the war juxtaposing Japanese suffering and Allied culpability.

I have discussed this 13-minute video at length because it is the key to understanding the historical consciousness of the new Peace Osaka. From start to finish, it presents a grand narrative that eschews any direct admission of Japanese responsibility for aggression and the few Japanese wartime atrocities that are mentioned (Nanjing, Chongqing, forced labor) are discussed vaguely or euphemistically. Consequently, Japanese war responsibility is implied to be equivalent to or even lesser than Allied war responsibility, which leads the visitor to the ultimate conclusion that Japan was victimized by the war. This rendition of history is conservative, and the influence of nationalist historians is evident on occasions, particularly in the references to the Tongzhou Incident.

Narratives of Victimhood and Stoicism

|

Figure 12: Zone C (new exhibits) |

The discussion of the video has clarified Peace Osaka’s new stance on what Japan did to others, but the museum’s real focus is on the people of Osaka and their experiences. Around the world, the combination of a justification for fighting (in Peace Osaka’s explanations “self-defense”, or in the case of the Allied nations “defeating fascism”) and the sacrifice, suffering, and stoicism of the populace in fighting for that cause is the foundation upon which a proud war narrative can be built.

In accordance with the renewal plans, the new exhibits place Osaka at the center. There are brief references to Osaka’s contribution to the war effort at the entrance to Zone C, where panels discuss “Asia’s largest artillery arsenal” in Osaka and the city’s role as the headquarters of the Imperial Army Fourth Division. But the exhibits in Zone C focus on Japanese suffering, with Osaka’s suffering portrayed as representative of the nation as a whole. There is a panel that gives the “Rapidly Increasing War Dead”. Japanese casualty figures are indicated on a map of Asia, but no indications of casualties suffered by other nationalities are given (Figure 12). There are sentimental displays of letters back to families in a section titled “People Waiting for Loved Ones Who Would Not be Coming Home”. And the reconstructed house in Zone C has a soundtrack which recreates a scene in a house just before the air raid. It starts with a little girl saying she is hungry. The mother admonishes the girl to do her best like her elder sister, who has been evacuated, her elder brother, who has been mobilized for war work, and her father, who was killed at the front. The little girl says she has done her best at school, and the mother says she has practiced bucket relays. This scenario about an “ordinary Osaka family” epitomizes how Japan as a whole was victimized by the war through the experience of a single family.

|

Figure 13: Zone E (new exhibits) |

The final zone not yet discussed in detail, Zone E (Figure 13), recounts Osaka’s reconstruction. It tells a story of resilience in the face of adversity. The introductory panel asks visitors to “consider how [Osaka residents] overcame various hardships and prevailed in challenging times”. Another panel titled “Human Suffering” says, “War brought much damage and suffering. Among those who suffered, there were disabled veterans, soldiers wounded in battle, wives who lost their husbands, children who lost their relatives in air raids and other people who bore deep pain and suffering” [author’s translation]. This section reflects the mission of the museum to focus on Osaka and provides a message of hope for people to take away from their visit in the form of Osaka’s brave response to suffering. Yet, once again, the focus is only on the sufferings of the people of Osaka and their stoicism and not on the responsibility of the military and the state.

Japanese Media Responses

The ideological conversion of Peace Osaka was celebrated as a victory by nationalist critics of the former exhibits. When the renewal plans were announced, Japan’s most nationalistic newspaper, Sankei Shinbun, crowed: “Removal of the ‘Nanjing Massacre’, Plans to renovate Peace Osaka, Masochistic exhibits to be normalized at last”.32 On the day that Peace Osaka reopened, 30 April 2015, an article describing the removal of exhibits about the “so-called ‘Nanjing Massacre’” and the “comfort women” ended with instructions on how to get to the museum on public transport.33 This endorsement was a marked change from previous disparaging comments about a “masochistic” museum beset with problems of “mislabeled and unreliable exhibits” that was visited only by “children and foreigners”. The Yomiuri Shinbun, typically described as conservative and close to the political establishment, avoided any explicit endorsement or criticism of the new exhibits, but in citing the position of Hashimoto Tōru and giving a comment from the daughter of an air raid victim, the Yomiuri gave voice to those endorsing the renewal without mentioning opposition to it.34 The Mainichi Shinbun noted in the sub-headline of its report on 30 April how “criticism of ‘masochism’ was pivotal” in the renewal and ended its report with a statement from the Network to Consider the Peace Osaka Crisis condemning the changes.35 The Asahi Shinbun, frequently a target of nationalists for its progressive stance on war history, had a full page article the morning after the opening ceremony lamenting how local museums with exhibits about Japanese aggression are finding it increasingly difficult to resist rightwing pressure. The Saitama Peace Museum had removed its mention of the “Nanjing Massacre” in 2013 under political pressure, it noted, while analysis by Harada Keiichi of Bukkyo University described how pressure from “netto uyoku” (rightist netizens) forced many exhibits into self-censorship.36

Press reaction, therefore, was mixed across the political spectrum of Japan’s contested war memories. Television news (see the YouTube videos in the appendix) also presented this mixture of reactions, but mainly used their visual format to contrast the appearance of the old and new exhibits.

Amid this mixed reaction, one of the key instigators of the change, Osaka governor Matsui Ichirō, expressed satisfaction: “This looks better now. I believe exhibits should not represent the view of one side when there are diverse perceptions (on the war).”37 Governor Matsui’s comments made it sound as if Peace Osaka had shed all ideological baggage and was now a balanced, neutral exhibit. But the protestors outside the building as he took part in the opening ceremony and toured the new exhibits with schoolchildren indicated this was not simply the correction of “unbalanced” exhibits: it was a political battle fought and won by conservatives.

Conclusions

The conversion of Peace Osaka from a progressive to conservative museum is a significant event in the recent battles over public history in Japan. It was a major victory for nationalist campaigners, who saw a reviled peace-oriented exhibit about Japanese aggression discarded and replaced by conservative exhibits. In the process, the museum has become an anachronism: a modern, high-tech justification of wartime ideology. The museum’s official name, Osaka International Peace Center, is now thoroughly inappropriate. There is little that is “international” (apart from panels in English) about a museum which presents a conservative narrative of Japan’s wars as a prelude to an introspective narrative of local suffering in air raids. There is little “peaceful” about the way in which the museum was bullied into changing its stance, and its potential for enhancing peace in Asia has been fundamentally undermined by its new ideology.

Peace Osaka is only one of over two hundred museums in Japan that depict the Asia-Pacific War (ranging from dedicated “peace” or “war” museums through to war-related exhibits in local/national history museums).38 It is not the only publicly-funded museum tackling issues of Japanese aggression and imperialism: the Kawasaki Peace Museum39 discusses Japanese aggression, while the Hokkaido Museum40 and Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum41 in Japan’s colonial peripheries address Japanese colonization of Ainu lands and the sufferings of Okinawans at the hands of the Japanese military, respectively. Private museums, such as the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace42, Kyoto Museum for World Peace43 and the Oka Masaharu Peace Memorial Museum44 in Nagasaki match the old Peace Osaka exhibits for their frankness in addressing Japanese war responsibility issues. The conversion of Peace Osaka, therefore, does not mean the end of exhibits in Japan depicting Japanese aggression, but as the Asahi Shinbun article on 1 May 2015 noted, they are now under considerable rightwing pressure.

The significance of the Peace Osaka case, therefore, goes well beyond the conversion of one museum. Peace Osaka (like many other municipal museums) opened at the beginning of the 1990s. This period seemed to offer a genuine opportunity for a more progressive official narrative in Japan that would facilitate a reconciliation process between Japan and its Asian neighbors. In addition to the opening of Peace Osaka in 1991, there were the eruption of the “comfort women” issue in 1992 and subsequent Kōno statement (“comfort women” apology) in 1993, the first statement about Asian suffering by a Japanese prime minister (Hosokawa Morihiro) at the Ceremony to Commemorate the War Dead on 15 August 1993, and the landmark Murayama statement of 1995. However, these progressive gains had been largely overturned by the seventieth anniversary of Japan’s surrender in 2015. The nationalist backlash started with campaigns against “masochistic” textbooks by the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (established in 1996), the same time that attacks on Peace Osaka began in earnest. While upholding the Murayama statement, Prime Minister Koizumi Junichirō caused anger across Asia with his annual visits to Yasukuni Shrine. There was another brief progressive interlude during the period of Democratic Party of Japan rule, 2009-2012 (primarily under prime ministers Hatoyama and Kan, 2009-11), but since the LDP regained power in 2012, Japan has shifted markedly to the right again. In 2013 Prime Minister Abe removed references to Asian suffering from his prime ministerial address on 15 August, thereby ending the protocol of the previous two decades.45 Repeated discussion in government circles of potential reviews of the Kōno statement and Murayama statement have clarified to the world that the heart of the current government is not in these statements, even if the government retains them as the official positions on paper. Japan continues its inexorable march toward possessing a proactive military capable of exercising collective self-defense. It is within this broad context that the conversion of Peace Osaka has taken place.

This macro picture raises the question of whether progressive official narratives on the war are sustainable in Japan. Peace Osaka’s experiences offer various insights into this question. In one sense, the conversion of Peace Osaka was simply the result of a change in local governments. Peace Osaka was set up when politicians backed a progressive stance, a key prerequisite for any progressive, publicly-funded museum. When prefectural and municipal governments opposing Peace Osaka’s progressive stance took power, they demanded a change and threatened to remove funding. Theoretically, a reversion to more progressive governments at the prefectural and municipal levels in Osaka could convert Peace Osaka back to progressivism again. This seems unlikely in the immediate future. But in any case, a perennial problem for progressive official narratives is their vulnerability to what is called bōgai in Japanese, or obstruction/interference. Repeated nationalist protests against the progressive exhibits at Peace Osaka and tactics that undermined the credibility of the museum (such as screening the film Pride and holding a Nanking massacre denial conference in Peace Osaka) demonstrate that nationalists have various weapons to employ against progressive official narratives. The tactics of bōgai are also used to attack the Asahi Newspaper and other organizations with progressive views.

However, war conservatism in Japan also has an Achilles heel. In the postwar period, war conservatism has been the default government position, but whenever progressives have achieved positions of power they have left an indelible mark on the official narrative. The 1995 Murayama statement became the basis for all subsequent prime ministerial statements and apologies. Peace Osaka’s former exhibits, despite some flaws as noted in this essay, set a new standard for progressive, official museum exhibits. The old Peace Osaka exhibits have disappeared, and what happens to the Murayama statement will become known in August 2015, but both are benchmarks against which the future official positions of national and local governments in Japan can and will be judged. In this respect, for both domestic and international observers of Japanese war memories, the conversion of Peace Osaka will remain an important case for years to come.

Peace Osaka may be only one museum, but it was internationally-known, publicly-funded and located in Japan’s third city (by population). In the coming years we will learn whether Peace Osaka has become a symbolic example of the “shift to the right” in Japan around the seventieth anniversary of the war end or whether it has simply slipped into relative obscurity as one of the dozens of local exhibits focusing on air raids. Analysis of visitation rates, visitor responses, and how schools use the new Peace Osaka for peace education visits, therefore, will be an important focus of research in the coming years. But, ultimately, the broader significance of Peace Osaka’s conversion is in demonstrating why progressive official narratives in Japan remain acutely vulnerable to the campaigns of nationalists. Its conversion reveals much about why the sort of national official narrative in Japan that would enable a genuine reconciliation process at the national level between Japan and its neighbors, particularly South Korea and China, remains elusive 70 years after the end of the Asia-Pacific War.

Appendix

Two YouTube videos showing how television news reported the opening of the new Peace Osaka are here and here (Japanese only):

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Mark Selden, Akiko Takenaka and Eric Johnston for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Author bio:

Philip Seaton is a professor in the International Student Center, Hokkaido University, where he is convenor of the Modern Japanese Studies Program. He is the author of Japan’s Contested War Memories: the “memory rifts” in historical consciousness of World War II (Routledge, 2007), Voices from the Shifting Russo-Japanese Border: Karafuto/Sakhalin (co-edited with Svetlana Paichadze, Routledge 2015) and Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido (Routledge, 2015). He also researches heritage tourism and has recently edited a special edition of Japan Forum (with Hugo Dobson), on Japanese Popular Culture and Contents Tourism. He is an Asia-Pacific Journal contributing editor and his website is www.philipseaton.net.

Recommended citation: Philip Seaton, “The Nationalist Assault on Japan’s Local Peace Museums: The Conversion of Peace Osaka”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 30, No. 3, July 27, 2015.

Notes

2 Reiji Yoshida (2013) “Hashimoto looks to deflect sex slave blame”, The Japan Times, 28 May 2013; AFP-Jiji/Kyodo (2014) “Hashimoto says WWII Allies set up ‘comfort stations’ after soldiers committed D-Day rapes”, The Japan Times, 16 June 2014.

3 URL: http://www.liberty.or.jp/index.php

4 The Asahi Shimbun (2015) “Peace museum, caving in to threats of closure, scraps wartime ‘aggression’ exhibits”, 1 May 2015.

5 For a more detailed explanation of my definitions of progressive, conservative and nationalist, see Philip Seaton (2007) Japan’s Contested War Memories: the “memory rifts” in historical consciousness of World War II, London: Routledge, pp. 20-28.

6 See for example Ian Buruma (1995) Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan, London: Vintage Edition, pp. 229-32; Roger B. Jeans (2005) “Victims or Victimizers? Museums, Textbooks, and the War Debate in Contemporary Japan”, The Journal of Military History, Vol. 69(1), pp.172-7. I described some of the disputes over Peace Osaka’s stance in Philip A. Seaton, Japan’s Contested War Memories, pp. 174-6, 220-1. The controversies surrounding Peace Osaka’s exhibits have been covered in greater detail by Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka (2007) and Akiko Takenaka (2014). Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka (2007) “Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus; Akiko Takenaka (2014) “Reactionary Nationalism and Museum Controversies: The Case of ‘Peace Osaka’”. The Public Historian, 36(2), pp. 75-98.

7 Takenaka, “Reactionary Nationalism and Museum Controversies”, p. 81-2.

8 Yoshinori Kobayashi (1998) Sensōron, Tokyo: Gentōsha, pp. 156-157.

9 Peace Osaka (2013) “Pīsu Ōsaka tenji rinyūaru kōsō”, p. 1.

10 Takenaka, “Reactionary Nationalism and Museum Controversies”, p. 85.

11 Takenaka, “Reactionary Nationalism and Museum Controversies”, p. 83

12 Asahi Shinbun (2000) “Ōsaka no heiwa hakubutsukan de Nankin daigyakusatsu kenshō kōenkai, kaijo mae, 150-nin kōgi”, 24 January 2000; Asahi Shinbun (2000) “Shimin dantai ga kōgi kaigō, Pīsu Ōsaka de Nankin daigyakusatsu hitei shūkai”, 9 April 2000.

13 Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka, “Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States”.

14 Asahi Shinbun, “Ribati Osaka, Osaka-shi no hojokin haishi kettei”, 3 June 2012.

15 For various Liberty Osaka documents related to the land issue, see http://www.liberty.or.jp/cp_pf/municipally owned land.html

16 Bunya Yoshito (2013) “Pīsu Ōsaka no kiki to shimin undō”, Shimin no Iken No. 139, 1 August 2013, p. 21.

17 Takenaka, “Reactionary Nationalism and Museum Controversies”, p. 85.

18 Narratives of victimhood can feature in war responsibility debates, either regarding the Japanese military’s responsibility for provoking the bombing by attacking the United States, or surrounding the military’s responsibility for failing to protect Japanese civilians from bombing by the Allies. A particularly well-known example in this latter context is the debate over whether the A-bombs could have been prevented if the Japanese military had accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration earlier.

19 Peace Osaka, “Pīsu Ōsaka tenji rinyūaru kōsō”, p. 3.

20 Peace Osaka, “Pīsu Ōsaka tenji rinyūaru kōsō”, p. 6

21 Takenaka, “Reactionary Nationalism and Museum Controversies”, pp. 88-89

22 A similar issue of nationalist opposition to graphic images of war violence being used as cover for an objection to a progressive narrative can be seen in the nationalist campaigns to remove the manga Barefoot Gen from school libraries. See Matthew Penney (2012) “Neo-nationalists Target Barefoot Gen”, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

23 This is the policy adopted by museums such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which recommends its exhibits as appropriate only for those aged 11 and older, and provides guidance on suitable exhibits for children under 8. See United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Plan Your Visit”.

24 Peace Osaka, “Pīsu Ōsaka tenji rinyūaru kōsō”, p. 6

25 See Nikkan Gendai (2006, trans. Nobuko Adachi) “Becoming an Ugly and Dangerous Nation! The Deterioration of Japan’s Fundamental Law of Education”, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

26 The latest development within textbook screening is for the Ministry of Education to insist that textbooks must state the government’s position alongside any alternative positions expressed by the authors of textbooks. This has effectively forced textbooks to converge around the government’s view on issues such as war history and territorial disputes. See Tawara Yoshifumi (2015) “The Abe Government and the 2014 Screening of Junior High School Textbooks”, Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

27 “Fifteen-Year War” emphasizes the connections between Japan’s wars starting with the 1931 Manchurian Incident and ending with defeat in 1945. The “China Incident” is preferred by nationalists because war was not officially declared between Japan and China and “incident” contains no overtones of aggression; and Great East Asia War is preferred as the Japanese name for the war used during the war (in other words, it is not a term forced on the defeated Japanese by the victors, such as Taiheiyō sensō, the Pacific War). Nanjing (great) massacre clarifies that a serious atrocity occurred. Nationalists, meanwhile, say iwayuru “Nankin gyakusatsu”, so-called “Nanjing massacre”, to indicate they disagree there was a massacre, and “Nanjing incident” contains no overtones of atrocity.

28 There are two versions of the video: a longer one aimed at adults and a shorter one aimed at children. I will refer to the longer one because it provides Peace Osaka’s new “grand narrative” starting in the late nineteenth century and ending in 1945 with the Osaka air raids and Japan’s defeat.

29 The wording is from the English subtitles of the video.

30 This includes the work of Brett L. Walker, Michele Mason, Richard Siddle, David L. Howell, Koike Kikō, Inoue Katsuo, Oda Hiroshi and others. For a full literature review of these texts and discussion of homegrown Japanese imperialism, see Philip Seaton (2015) Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido, London: Routledge, Chapter 2.

31 See for example Watanabe Shōichi (1995) Kakute Shōwa shi wa yomikaeru: jinshu sabetsu no sekai wo tatakitsubushita Nippon, Tokyo: Crest Sensho, p.275. The reference to the Tongzhou Mutiny in Watanabe’s book was picked up by Kobayashi Yoshinori in Sensōron (p. 135-136). A more recent indication for the importance of the Tongzhou mutiny to nationalists is a news item (posted 9 April 2015) on the website of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Tsukurukai) announcing that its school textbook had passed the Ministry of Education’s screening, Tsukurukai proclaimed, “The birth of the only history textbook which does not write about the fabricated ‘Nanjing Incident’ but does write about the actual ‘Tongzhou Incident’”. The Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (2015) “Kyokō no ‘Nankin jiken’ wo kakazu, jitsuzai no ‘Tsūshū jiken’ wo kaita yuiitsu no rekishi kyōkasho ga tanjō! Jiyūsha no ‘Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho’ ga Monkashō no kentei ni gōkaku”, 9 April 2015.

32 Sankei Shinbun (2013) “‘Nankin daigyakusatsu’ tekkyo e, Pīsu Ōsaka kaisō an, jigyaku tenji yōyaku seijōka e”, 18 September 2013.

33 Sankei Shinbun (2015) “‘Nankin daigyakusatsu’ shashin haiki, ianfu tenji mo tekkyo, henkō tenji / jigyaku shikan to hihan uke, Pīsu Ōsaka kaisō ōpun”, 30 April 2015.

34 Yomiuri Shinbun (2015) “Ōsaka kūshū no tenji chūshin ni. Pīsu Ōsaka, kaisō ōpun”, 30 April 2015.

35 Mainichi Shinbun (2015) “Pīsu Ōsaka: saikai, kūshū to fukkō, jiku ni ‘jigyakuteki’ hihan”, 30 April 2015.

36 Asahi Shinbun (2015) “(Sengo 70 nen) Kieru ‘shinryaku’, chijimu kagai tenji, Pīsu Ōsaka, shisetsu sonzoku e zentekkyo”, 1 May 2015.

37 The Asahi Shimbun (2015) “Peace museum, caving in to threats of closure, scraps wartime ‘aggression’ exhibits”, 1 May 2015.

38 Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka, “Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States”.

45 Abe Shinzō, “Address by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the Eighty-Sixth Memorial Ceremony for the War Dead”, 15 August 2013.