Doing Violence to Buraku History: J. Mark Ramseyer’s Dangerous Inventions

BY: Timothy Amos, Maren Ehlers, Anne McKnight, David Ambaras, and Ian Neary

Introduction

We are researchers with strong concerns about J. Mark Ramseyer’s (hereafter JMR) article “On the Invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcastes in Japan.”1 We are active in various disciplines and have published work on aspects of Buraku history and literature, as well as the history of slums, deviance, and marginality. The article comprises one part of a larger body of writing by JMR in recent years that has been critiqued and refuted for its misrepresentations of sources, which have in turn created larger historiographic misunderstandings that reproduce discrimination against Burakumin.2 At the same time we raise these questions, in Japan, scholars and representatives of the Buraku community have openly rejected the author’s writings on Burakumin, including this 2019 article. They have specifically questioned his research methods; his use (and abuse) of evidence; his characterizations of people, problems, and processes; and the validity and truthfulness of his various claims about (1) the status of pre-modern Buraku occupations and social mobility, (2) the origins and nature of the Suiheisha, the first nationwide Buraku social movement, and (3) the character and impact of government Dōwa subsidies on Buraku communities since the 1960s.3

Burakumin are usually understood as Japan’s largest social minority group, the descendants of premodern outcaste communities (named kawata / eta / chōri, hinin, et cetera) engaged in various occupations but particularly leatherwork. They have generally been treated as “outcaste” communities, because there is strong evidence of a particular form of institutional and societal discrimination that can be demonstrated to have worked to exclude or marginalize them. While scholarship is certainly not uniform in relation to how to understand the origins of these communities, the nature of their treatment in early modern Japan, and the reasons for the continuing existence of Burakumin in the modern era, no reasonable reading of this body of work would lend itself to supporting JMR’s assertions. While JMR does engage with some of the available literature, he only appropriates some scholarly arguments in order ultimately to distort them.

JMR misleads on the nature of Buraku history, misrepresents core problems such as the nature of Buraku discrimination, and offers exaggerated and at times blatant mischaracterizations that affect the historiography that emerges from his claims. In key instances, JMR does not actually cite persuasive secondary scholarship, let alone primary sources, but has simply presented assertions as empirical reality. From a fact-checking point of view, it is clear that this paper should never have been published simply based on the amount of basic errors it contains.4 Because these instances tend to cluster around particular contentions, we have divided them into three sections. Each section is problematic on its own; but linked, they combine to distort the realities of Buraku history and paint a picture of a violent social movement otherwise disconnected from social reality, and responsible for a bad reputation that is actually conferred by this article itself. In this statement, we outline evidence of substantial misrepresentation, misreading, miscontextualization, and distortion of sources pertaining to the three core arguments.

These three arguments are: first, that Burakumin were historically simply poor peasants (the “poor peasant” thesis); second, that in the early twentieth century, “fringe-left Burakumin” and “self-described Bolsheviks lauched [sic] a buraku ‘liberation’ organization” (1) by “redefin[ing] the buraku as a leather workers’ guild” (5) and creating a “fictive identity” (1) based on a “fictive past” (63) (the “modern self-construction” argument); and third, that Burakumin “pioneered a shakedown strategy that coupled violent accusations of bias with demands for massive amounts of money” (1), becoming an organization geared to extorting Japanese society with the backing of the state in the postwar period (the “state-enabled dysfunctional interest group” argument). These individual arguments, when presented together, put forward a central thesis that strongly insinuates that Burakumin are parasitical if not indeed heavily comprised of criminals.

All three arguments are diametrically opposed to what might be legitimately concluded from a survey of existing historiographical literature. Despite considerable interpretative diversity, scholarship since at least the 1980s has acknowledged three things: that the category of status (mibun) is foundational to the creation of distinctive “outcaste” groups in premodern Japan; that important historical continuities between such groups and modern Buraku communities exist; and that both institutional and societal discrimination against such communities continued throughout the course of the twentieth century. Where JMR engages with this scholarship, it is to manipulate it, along with historical sources, in order to present a polemical and offensive conclusion.

The problems in JMR’s article thus go far beyond his poor academic practice (although this in itself should be ample grounds for retraction). His misrepresentations add up to a political statement about Burakumin that can only be called derogatory. It is derogatory because JMR places the blame for what has been called “Buraku discrimination” squarely at the feet of the communities themselves. Burakumin, in this paper, largely become a product of their own making, their coherent sense of minority belonging purportedly rooted in a fake history, and their strategies allegedly informed by a Marxist toolkit for identity politics that the author sees as having spread among disenfranchised communities at the time of the movement’s formation. Burakumin, according to the author, framed their experiences in a way that permitted them to maximize their own interests and profit, all the while blaming the rest of society for the very legitimate concerns it had raised about them. They built organizations dedicated to “liberation” that basically functioned like the Japanese mafia, that is when Burakumin were not allegedly supplying community residents to the actual mafia.

This blame-the-victim approach reveals connections to a broader racist agenda, through which JMR uses Japanese studies as a means to vent opinions about race in the United States without incurring the blowback that would come from a more direct statement. In a 2019 paper, for example, he invokes a hoary American reactionary trope to argue that “the worst enemies of an underclass are often its own elites,” but declares that he has chosen to “illustrate this logic” with examples from Japan (the Burakumin, resident Koreans, and Okinawans); and that he “avoid[s] the well-known ethnic disputes in the U.S. and elsewhere deliberately but reluctantly — for the simple reason that the hyper-polarization within the academy has made candid discussion of ethnic politics extraordinarily hard.”5

More recently, JMR has nodded approvingly in the direction of the notorious 1965 Moynihan report that blamed Black hardships on the “pathology” of the Black family, and notes that Moynihan “found himself attacked mercilessly” for having written of “high illegitimacy rates,” the absence of fathers, and the consequent failure of children to “internalize basic social norms” due to the lack of “a stable framework that includes both biological parents.”6 Yet JMR appears to have been nursing this view for some time. In a 2011 review of a book on Japanese law, he speculates, gratuitously, that “Abortion is common in the United States as well, but often in the urban ghetto” and that women there choose to terminate pregnancies largely because “I suspect many [fathers] have simply disappeared.”7 Similarly, JMR has blamed Koreans in Japan for incurring the animosity and violence directed against them because of their own antisocial behavior and criminality. One article in which he has made such claims has in fact been pulled from publication pending “significant” revisions, with the volume editors calling the initial decision to publish such content “a very regrettable mistake.”8 The stakes of these substitutions, speculations, and spurious allegations could not be clearer: JMR is smuggling American-style racist arguments into Japanese studies, thus providing rhetorical tools and scholarly legitimation to those in Japan who would apply them to their own campaigns against minority groups and minority activists, including the Burakumin.

How such a patently false and offensive polemic secured 95 pages of space in an academic journal is beyond our comprehension. But now that the author’s arguments about Burakumin are circulating in the public sphere, and even being used for troubling purposes by people with antagonistic motivations in Japan and elsewhere, it is necessary to both expose the fundamental and extensive flaws in JMR’s work and to present concrete information that can serve to promote genuine understandings of Burakumin and their history for a scholarly and a wider public.

The article’s publisher, De Gruyter, maintains a section on “reporting standards” whose principles are based on the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). De Gruyter’s Reporting Standards document sets out a clear standard that this article violates: “Authors reporting results of original research should present an accurate account of the work performed as well as an objective discussion of its significance. Underlying data should be represented accurately in the manuscript. A paper should contain sufficient detail and references to permit others to replicate the work. Fraudulent or knowingly inaccurate statements constitute unethical behavior and are unacceptable.”9 Our desire is to see both the article retracted and for current and future generations of students who encounter his work and/or its arguments to have sufficient resources to understand why the content of the article should be dismissed. The remainder of this article sets out the misrepresentations, distortions, and decontextualizations that pertain to the three main arguments. We are releasing this article in two venues and formats: (1) as an article in The Asia-Pacific Journal, and (2) as a live document on the Concerned Scholars website, where we will provide further examples of JMR’s misrepresentations, distortions, misuse of evidence, and basic errors in the “Invention of Identity Politics” article. The live document will thus be housed alongside and complement Amy Stanley et al., “‘Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War’: The Case for Retraction on Grounds of Academic Misconduct,” which addresses JMR’s recent article on the history of the comfort women.10

1. The “Poor Peasant” Thesis

One of JMR’s core contentions in his paper is that the overwhelming majority of early modern Burakumin ancestors–defined by the author as “kawata”–were “poor peasants” rather than leatherworkers, meaning that they cannot have experienced discrimination because of their involvement in that profession. According to the author, if the Burakumin’s early modern ancestors were being discriminated against at all, it was because they were poor.11

JMR’s position clearly flies in the face of existing scholarship and fails to accurately represent the history of early modern outcaste groups in Japan. While there have been and will continue to be debates about the historical origins of Burakumin in Japan and the nature of discrimination against early modern outcaste groups, the context for the debate over the last half century has almost always been the extent to which the early modern Japanese state targeted groups referred to as kawata / eta / chōri, hinin, et cetera for special kinds of discrimination. Scholars have queried the historical origins of particular communities and worked intently over the course of the twentieth century to understand the precise reasons for their emergence. Given the tremendous social diversity across the Japanese archipelago during the early modern period, scholars have been judicious about their hypotheses and interpretative progress has been made through debate and the close examination of available evidence. Recent scholarship, moreover, tackles the logic of the social and political system itself, in an attempt to better understand what parts of early modern experience were common to all “status” groups and what parts were unique to some. Arguments that focus on the political origins of the discrimination in early modern Japan have tended to predominate for obvious reasons. These arguments, while not uncontested, are also supported by the historical record, and have enabled Buraku communities to receive redress from the state to counter the structural discrimination that has shaped their lives and experiences.

Despite the sometimes substantial interpretative disagreements, there is in fact an abundance of historical evidence and reliable scholarship that can permit us to comfortably conclude that kawata / eta / chōri communities were distinctive communities engaged in leather procurement and production, agriculture, as well as a number of official duties and other activities. They were subjected to institutional as well as societal discrimination rooted in official status distinctions and at least to some extent in “pollution” ideology. There is, conversely, no real evidence to suggest that kawata / eta / chōri were basically “poor peasants” who could avoid adverse treatment through wealth creation and social mobility. The argument put forward by JMR can only be substantiated by misreading or distorting available evidence.

Status (mibun) and rule by status defined the very nature of early modern Japanese society. People belonged to specific status groups, which enabled them to be recognized within early modern society.12 Kawata / eta / chōri were organized in a large variety of locally grounded status groups that in many parts of Japan combined to form larger regional clusters (but never one unified status group covering the entire country). It was through the status groups that kawata / eta / chōri shouldered a variety of rights and duties. Historian Yokoyama Yuriko summarizes this in relation to kawata as follows: “[K]awata status entailed groups of kawata specializing in leatherwork, monopolizing hide collection areas (territories) for the purpose of leather hide procurement, and assuming collective responsibility for various duties including the official supply of leather to the authorities and/or engaging in execution duties.”13 In other words, status significantly defined the nature of the early modern political and social system, and heavily determined both the relationships within and between particular groups in society and their relationships to authorities. In such a system, occupational duties such as leatherwork were defining features of a particular status (in this case kawata / eta / chōri) and of its relationship with authorities, regardless of whether there were instances in which individual villagers did not engage in that particular activity.

“Eta” in Edo shokunin utaawase, Ishihara Masaakira,

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It is clear, moreover, that status, and by extension outcaste status including kawata / eta / chōri groups, was shaped by particular policies. Serious scholars have long paid attention to the emergence of systems of registration and official duties when they attempt to comprehend the extent to which the life experiences of early modern subjects were structurally determined. A focus on these systems is important because the outcaste / Buraku problem is not simply a problem of descent (whether by blood or adoption) and occupation, but also one of geographical anchoring through systems of legal registration that functioned in complex ways.14 As Asao Naohiro has pointed out, cadastral records and population registers functioned alongside a broad array of other records including temple registers to determine kawata communities in the early Tokugawa period.15

Circulation of skins and hides in early modern Japan was substantial and there is ample evidence that skins and hides were being almost exclusively sourced from kawata / eta / chōri communities. In 1842, the Osaka City Magistrate, Abe Shōzō, claimed that 100,000 skins from central Japan and the provinces further west annually entered Watanabe village, a prominent kawata community, and that despite the famines in recent years, Watanabe was still processing 70,000 skins annually, some of them imported from the Korean peninsula.16 And while the exact numbers are difficult to determine in eastern Japan, the number of hides being processed in Asakusa (the headquarters of the eta chief Danzaemon) was 12,200 in 1874, and it is clear that these items were still being sourced through traditional chōri networks in the early Meiji period.17 Such a large scale leather trade was predicated upon the existence of kawata / eta / chōri communities from which these skins could be sourced.18 Furthermore, even if one were to try to make an ill-judged case that kawata / eta / chōri in early modern Japan should be called farmers, the leading early modern outcaste centers in Osaka, Edo and other major castle towns were clearly not agricultural, but heavily involved in trade and manufacturing, particularly with regard to skin and its products. These urban outcaste communities not only sourced large numbers of hides from rural outcaste communities, but also exercised control over outcaste villages in the surrounding countryside under the framework of status-based rule.

Kawata / eta / chōri engagement in leatherwork and other duties such as penal execution could and did become an important source of discrimination against them. JMR rejects the importance of “pollution” (generally referred to as kegare), that is, the notion that kawata / eta / chōri were considered impure because they skinned the hides of cows and horses and executed criminals and therefore had many encounters with death, blood, disease, as well as other potentially linked sources of defilement.19 (The term eta itself means “greatly polluted.”) While there is a more recent body of scholarship that deemphasizes ritual pollution in relation to kawata / eta / chōri communities, JMR neither cites this scholarship nor reveals to the reader that it is a perspective emerging out of historical debates about how best to understand the early modern status system. Nor does he acknowledge that pollution ideology is by no means the only or even dominant way of explaining the early modern treatment of outcastes. Although it is possible to deemphasize the importance of pollution ideology, the link between kawata / eta / chōri communities and pollution cannot simply be dismissed as something that was made up in a later period, or imagined by later scholars duped into a certain mode of thinking about Burakumin. Of course, no scholar in the field would carelessly assert that it was uniform across time and space. But manifestations of such discrimination are too numerous to mention.20 Minegishi Kentarō, for example, a scholar with whom JMR is clearly familiar, has discussed phenomena such as marital avoidance and insistence on the use of separate eating vessels in his work, demonstrating that “customary discrimination” (shūzokuteki sabetsu) was widely practiced in premodern Japan.21 Numerous domains and territories issued orders that forced kawata / eta / chōri to dress differently, to maintain separate registers, and to refrain from entering certain spaces such as peasant houses.22 One of the more pernicious practices was the issuance of discriminatory posthumous names (sabetsu kaimyō); scholars have identified grave markers for members of these communities that contain words such as “beast” (chiku).23 This dehumanizing rhetoric of pollution clearly exceeded the condescension towards inferiors one might expect from a hierarchically organized society, and it extended to the very top of the kawata hierarchy. Around the time of the Meiji Restoration, the leader of the Tokyo Asakusa kawata / eta / chōri community, Dan Naiki (the last Danzaemon), referred to “several hundred years of continual abuse.” Dan Naiki lamented how “even though we are no different from other human beings born under heaven, the fact that human associations are [still] not possible is a truly deplorable fact.”24 Even when taking into account the possible rhetorical posture he may have been taking at the time of such utterances, it is clear that Dan Naiki was himself the subject of vulgar discriminatory talk by members of the late Edo literati. The author Shibata Shūzō, for example, commented to a friend in a private communication that it was “polluting to even hear” (jitsu ni kiku mo kitanarashiki koto) that a salon-like literary circle had sprung up around Danzaemon.25

Danzaemon family gravestones bearing the surname Yano at Asakusa’s Honryūji Temple

Source: Timothy D. Amos

Plainly the lives of kawata / eta / chōri could be and were valued differently to other members of the population during the early modern period and they were treated differently because of this evaluation. Perhaps the most blatant form this could take was to value the life of members of the kawata / eta / chōri communities differently than others, including the lives of peasants. Examples can be found across many regions. In Kōzuke province, for example, a clash occurred in 1839 that started with a chōri (kawata / eta) and a peasant drinking together and the latter reportedly insulting the former: “Even if I killed seven eta, I would only need to offer up one white dog for execution in return.”26 What began as a discriminatory utterance rapidly escalated into a dispute between the respective chōri and peasant villages that needed to be mediated by the local bannerman’s representative. In the Tenpō era (1831-1845), “eta hunt/s” (etagari) took place that targeted kawata for “exposure” when they attempted to pass as members of non-outcaste society.27 While it is impossible to pinpoint the underlying motivations of the perpetrators of violence and discrimination in each and every case, the idea that kawata / eta / chōri were “dirty” or “polluted” certainly underpinned justifications and rationales for particular actions on the part of other members of society. To completely deny such discrimination against kawata communities is to fail to comprehend the nature of their historical experiences.

JMR does not deny the experience of discrimination, but explains it as a consequence of the kawatas’ poverty. Poverty was widespread in Tokugawa Japan and indeed resulted in certain kinds of discrimination. Nor can there be any doubt that many kawata were poor and poverty could factor into the treatment they received from others. However, this does not negate the simultaneous presence of another kind of discrimination specifically directed against kawata and the members of other outcaste communities. Landless tenants, slum dwellers, and day laborers may have been treated with condescension and barred from marrying their social betters, but unlike kawata, they were allowed to live in the same neighborhoods and villages, and were subjected to the same household registers and laws. They did not need to fear being compared to animals, and their bloodline did not mark them for social exclusion. In fact, lower-class commoners were often particularly eager to insist that discriminatory rules and segregation against kawata and other outcastes were strictly enforced.28 Conversely, rich kawata did not evade discrimination against outcastes on account of their wealth, as seen above, for example, in Danzaemon’s case. As JMR himself notes (34; 36-37), wealth could even intensify the blowback against kawata, both from the authorities and from commoner neighbors fearing for their status and resources.

It is also patently not the case, as JMR claims, that government regulations targeting eta and hinin were only issued in the second half of the Tokugawa period. One early reference to “eta” in Tokugawa shogunate legislation occurred in 1657, in a nine-article charter which introduced a number of governance issues and mentioned eta and hinin in relation to their potential criminality.29 A Tokugawa order issued in 1721 attempted to force eta to wrap their silver taxes in paper first with an inscription “eta payment” before submitting them to the authorities.30 Such sources undercut JMR’s point that government regulations and sumptuary edicts were issued only in the second half of the Tokugawa period and in response to kawata economic successes.

Social mobility in relation to early modern kawata / eta / chōri is clearly an important question. There is some evidence for kawata leaving their communities and blending in with commoners, especially in large cities, but JMR greatly exaggerates it by taking other scholars’ work out of context, misrepresenting their arguments, and making unfounded assertions. For a detailed check of these points and supporting references, we refer the reader to Toriyama Hiroshi’s analysis in “Problems with the References to Historical Documents in J. M. Ramseyer” in this journal. JMR does not perform any primary source analysis himself to back up his claims about the early modern period. Instead, he draws mostly on certain Japanese scholars publishing in the last three or four decades, whom he credits with “an increasingly sophisticated and intellectually independent corpus of work.” He thus seeks to set these historians apart from “mid-century scholars,” who were “overwhelmingly Marxist, and often mechanically so” (5) as well as from practitioners of “modern-buraku studies,” “who produce entirely predictable work of at-best dubious veracity” (6). However, JMR cannot claim to affiliate himself with these scholars, because he greatly distorts their arguments. The references discussed by Toriyama are only the most egregious among a large number of faulty citations.

The conclusion about the “poor peasant” thesis of Burakumin can only really arise if JMR ignores or twists existing literature. What the “poor peasant” thesis ultimately attempts to do is to undercut Burakumin claims to a long history of oppression at the hands of mainstream Japanese society. It is, in short, a declaration of war on a minority, by asserting that both the identity they assume and the discrimination they purport to have experienced is fake. This political assault on Burakumin takes place despite the fact that even the Japanese government in 1969 recognized the historical roots of Buraku discrimination when they passed the first of a series of Special Measures Laws to address the problem: “The Dōwa [Buraku] problem is an extremely serious and grave social problem whereby some groups of Japanese nationals are economically, socially, and culturally placed in a low social position through discrimination that originated in the social status structure formed during the historical developmental process of Japanese society; and have their fundamental human rights violated even in contemporary society, in particular, failing to have their civil rights and freedom fully protected, which are guaranteed to all people as the principles of modern society.”31

2. The “Modern Self-construction” Argument

JMR widely asserts throughout his article that Burakumin in the 1920s created themselves as a group of historical outcaste descendants for completely self-serving purposes.32 The term “fictive” recurs multiple times in the article (“fictive identity,” “fictive origin,” “fictive past”), and works to discredit legitimate historical work as well as the many writings, in a large variety of sources and across centuries, that have testified to grievances suffered by Burakumin and their ancestors. Although the charge against fiction is the major indictment in this article, no source is listed to locate where this alleged “fiction” is perpetrated, though the date of 1922 repeatedly cited by JMR is most commonly associated with the Suiheisha Declaration, issued by the newly-formed organization that advocated for Burakumin rights on a nationwide basis. That document is a short statement that declares the intent to pursue “dignity” on behalf of Burakumin because of past discrimination; the Declaration uses Christological metaphors (thorn of crowns) as well as language that links the suffering of Burakumin to discrimination we discussed earlier that derived from ideas about ritual pollution.33 Placed in its historical context, this is a commonplace statement of ethnic and/or national self-determination or universal rights issued by movements that arose after World War I, including the March 1, 1919 Declaration of Independence by Koreans under Japanese colonial rule.

JMR’s argument about an allegedly “fictive” movement fails to account for two things: first, that Burakumin had a host of grievances that were acknowledged throughout society and even among state actors; and second, that scholarship has, as we documented in the previous section, affirmed the real connections between early modern outcaste groups and Buraku communities in the modern era, with legal, political, and social recognition of these connections still ongoing. If a specter of fiction is haunting Buraku history, evidence suggests it is one of JMR’s own conjuring. JMR ignores historical continuities between communities, including in relation to the kinds of discrimination they faced and collective efforts to combat that, and offers no convincing explanation about the grounds for why such connections should be dismissed in favor of a modern self-construction argument. The article further sidesteps important definitional issues pertaining to who Burakumin are and mishandles core survey data that is used to reveal information about them. The argument presented also reveals little comprehension of the complex forms modern discrimination takes or the substantial efforts by a range of actors to eliminate it prior to the 1922 establishment of the Suiheisha.

Beyond fallaciously positing the Suiheisha as the original catalyst of discontent, JMR proffers descriptions of the Suiheisha and its activities that are inaccurate and skewed. They offer a caricature whose political function is to directly delegitimize the modern Buraku liberation movement.

Scholarship that attempts to take seriously the ideational dimensions of Buraku history (i.e. work that takes seriously the contexts in which people represent themselves and their history as an important factor in historical representation) has become increasingly important in recent years.34 Undoubtedly, not all attempts to explain the emergence of “modern Buraku communities” are entirely convincing. Certain modern communities (or people) over time became uncritically identified with early modern outcaste communities despite only tenuous linkages. However, the claims made in this article by JMR enter into the realm of a perverse kind of philosophical idealism, where Burakumin regardless of historical context and social circumstances are somehow able to construct themselves and their past in an exact manner of their own choosing for personal gain. Such a position flies in the face of existing scholarship and misrepresents the history of Buraku activism in modern Japan. Even materials JMR cites to discredit Burakumin as violent contextualize Burakumin actions in highly sympathetic terms of “deep suffering and strong solidarity,” functions of discrimination.35 JMR’s failure to take into account the material constraints that Burakumin lived under, as well as the kinds of options available to them as they wrestled with institutional and social discrimination, lead to a colossal distortion of their history and experience.

To begin with the most elementary of problems, there is the basic issue of labeling — the various nomenclatures which described Burakumin and their ancestors. While the semantic and symbolic contents of these labels shifted over time, they still retained their discriminatory character. JMR’s comments on this issue are thin and difficult to take seriously (38).36 Early modern outcaste communities were under no illusion about the nature of the labels applied to them. Dan Naiki, for example, in the above quoted communication, referred to the label “eta” (which, as noted above, means “greatly polluted”) as “two despicable Chinese ideographs” (niji no shūmei). In another communication written to his subjects he referred to the “outlawing of the label eta” (eta no meimoku on-nozoki) and the “expurgation of their past bad name” (jūrai no shūmei issō).37 When these labels were outlawed in 1871, moreover, others, such as shinheimin (“new commoner”), came to supersede them, while the older labels were slow to die, creating simultaneous referential systems for discrimination. The bearer of the label “new commoner” was obviously singled out as a non-standard, improper kind of commoner.

The non-standard nature of the label “new commoner” is important because it was used frequently in household registration (koseki) documents. The 1871 Household Registration Law required every household to register its members with local government authorities in the same geographical locality. The use of terms such as shinheimin in these documents legally marked particular communities in relation to their former outcaste origins in ways that continued to affect the households long into the postwar period. It is common knowledge among historians of Buraku history that the 1872 household registers are particularly problematic documents for Burakumin as they can be used to demonstrate beyond much doubt the connections between particular individuals and outcaste ancestry. Perusal of these records was restricted by the Japanese government from the late 1960s in order to protect members of Buraku communities from being discriminated against by unscrupulous background checks.38 The public access of these documents is still actively monitored and they are removed from circulation by Japanese government ministries today.39 In an article so ostensibly concerned with extra-legal violence and published in a journal of legal studies, it is unexpected and concerning that these points pertinent to legal frameworks remain unmentioned. Clearly to do so would result in the need to acknowledge the existence of communities with premodern histories that suffered as a result of modern forms of social and institutional discrimination.

The denial of continuity between premodern and modern discrimination, however, goes beyond labeling and registration issues. Particular groups of people identified as shinheimin became the subject of popular calls for emigration to help colonize Japan’s northern border during the Meiji period. Such discussions were hardly new to that era, as discussions about the emigration of outcaste groups to Ezo had emerged in the second half of the Tokugawa period. In the Meiji period, the central government issued directives to prefectural governments to further affirm the desirability of such policies and prefectural government officials even “acted on occasion to facilitate buraku emigration.”40 As Noah McCormack noted, Meiji period emigration proposals were based on beliefs that former outcastes had numerous faults which for the purposes of nation-building were best overcome outside of Japan proper.41 JMR’s sidestepping of the movement to relocate its “former outcastes” to other places, both at the levels of public discussion and actual policy, distorts modern Buraku history. Neglecting to warn readers about the discrimination that confronted shinheimin in the Meiji period, as well as the serious power imbalance that existed between them and government and other elites in Meiji society, seriously misrepresents Buraku historical experience.

JMR’s predilection for explaining Buraku discrimination simply as an effect of poverty distorts his ability to account for modern discrimination against people who came to identify as Burakumin. As historian Suzuki Ryō has pointed out, there is a complex story behind the ways in which early modern status systems were transformed in the modern era. On the one hand, such systems were reshaped through the pervasive forces of capitalism, but at the same time they also remained a product of local ways of instituting modern systems of land ownership, education, and other forms of participation and belonging as Japan attempted to join the community of modern nations.42 Some individuals and communities chose to try to adapt to mainstream commoner societal expectations, but this had limited impact on resolving discrimination at the local level. Some former outcaste communities attempted to move out of the traditional occupations and industries that previously sustained them, and work towards social mobility through capital accumulation and educational advancement. Such efforts were often spearheaded by wealthier members of the community.43

Former outcaste communities eventually came to be targeted by the government for local improvements to “harmonize” (yūwa) their position within mainstream Japanese society. Social conciliation was widely perceived to be an effective strategy for combating the problems that came to be associated with Buraku (and of course with non-Buraku slums) such as poverty, low matriculation rates, criminality, and disease. Government officials, industrial stalwarts, and religious and community leaders pushed the hardest for such harmonization in the early twentieth century, but members of Buraku communities also contributed to these efforts both individually and at an organizational level.44 Over time, however, the earnestness for self-reform within many Buraku communities was overrun by skepticism. Younger community members were increasingly unsure of the reliability of a story that framed the reasons for their continued discrimination in internal terms. This growing self-realization is what led to the Suiheisha movement discussed further below. It was essentially an indigenous rights struggle in Japan by a social minority. But it was also, as Suzuki points out, a form of regional democratic struggle that can be divided up into numerous phases and that pointed to massive dissatisfaction with local arrangements that locked Buraku modern communities into deleterious relationships with neighboring communities and the government.45

While there was occasionally intriguing overlap between shinheimin districts (increasingly labelled “Special Buraku” districts) and newly formed slum areas in urban settings, it is obvious that JMR conflates them and has not done the work to be able to tell the difference.46 Among several examples, most egregiously, he refers to Osaka’s Nago slum as a Buraku area when it was in fact an urban slum, thus misinterpreting the key primary sources on which he bases his assertions (48).47 And while some late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century commentators such as Kagawa Toyohiko did proffer the mistaken claim that Japan’s modern slums were the outgrowth of Burakumin communities, JMR merely carries forward their assumptions without conducting the critical source analysis incumbent on any responsible historical scholar.48 This conflation of poor districts and areas historically linked to premodern outcaste groups clearly derives from the author’s deterministic understanding of the relationship between poverty and Buraku discrimination. While the poverty of certain Buraku areas did feed popular prejudice against them, “Buraku discrimination” (that is, discrimination directed at presumed descendants of early modern outcastes) was still alive and well in prewar Japan, and even supported at an institutional level by the state. A good example of this is the 1933 Takamatsu court case where a Burakumin who married a woman without “revealing his background” was successfully sentenced for abduction. This case clearly signified to the Suiheisha and members of Buraku communities that official government institutions in the hands of discriminators could not be relied upon by members of Buraku communities to secure justice against discriminatory attitudes and actions.49

JMR further ignores the ways in which even before the founding of the Suiheisha, members of Buraku communities attempted both individually and collectively to combat unique forms of discrimination that targeted them. Groups such as the Yamato dōshikai (Yamato Brotherhood Society) worked to bring about national and social cohesion. Actions were also taken at the national level to unify local movements and encourage social harmonization, most notably with the formation of the Teikoku kōdōkai (Imperial Way Society) in 1914, an organization formed to allay the possible negative ramifications for Japan if leftwing thought permeated deeply through these communities.50 Such movements and various frustrations with them inspired other community residents to self-mobilize. “Special Buraku people,” in the emerging language of the day, certainly began to unite around a shared history of oppression and became increasingly conscious of radical ideas effective in popular mobilization and the international labor movement. But this growing awareness is an act that needs to be understood with such historical background as context. It was not an act of self-creation for selfish gain as JMR asserts, but rather an important stage of self-realization based on enhanced recognition of the gross failures of prewar Japan’s political institutions’ ability to protect Buraku communities.

Probably the most egregious parts of the “modern self-construction” argument pertain to JMR’s descriptions of the activities of the Suiheisha (National Leveller’s Association). The organization was formed in 1922 with branches quickly springing up around the archipelago. The organization aimed to “organize a new group movement” through which emancipation would be realized through the promotion of “respect for human dignity.”51 Yet JMR sets about demonizing people central to the movement. Suiheisha leaders are portrayed as violent underworld figures who extorted others for financial gain. Tactics such as denunciation (kyūdan) meant to decry discrimination are begrimed as thinly veiled attempts to shake down others for financial gain. Official government reports of events are ascribed an immutable truth value, while the writings of Suiheisha individuals are either represented as dubious or filtered through the author’s predetermined theoretical framework as perpetrators of violent identity politics. For a detailed critique of JMR’s problematic portrayal of the Suiheisha, we refer the reader to the analyses by Asaji Takeshi and Hirooka Kiyonobu as well as Fujino Yutaka. Here we focus simply on the crooked representation of kyūdan in the author’s work.

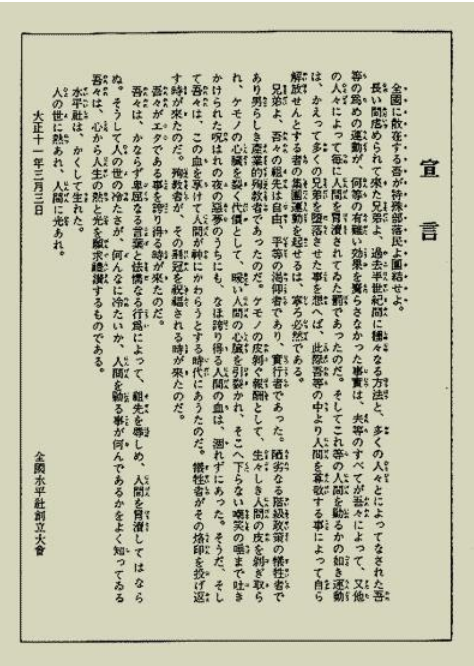

Suiheisha Declaration (1922)

Source: Wikipedia Commons

JMR does not give the reader any sense of the level, scale, or context of the Suiheisha’s denunciation campaigns. He does not mention that the total number of such campaigns conducted between 1922 and 1925 alone could well have numbered as high as 3,000.52 Nor does he explain the social consequences of engaging in such activism. Instead, he portrays kyūdan incidents as a kind of one-sided violent protest rooted in grudges or trivialities that were ultimately about personal gain. For example, JMR offers the following composite image of what he considers a typical denunciation:

In the typical case, one child would call another “eta.” The burakumin child would complain to his parents. The parents would obtain an apology from the other child’s parents. They and others from the buraku would then demand an additional apology from the teacher for not teaching the children properly. They would demand an apology from the school principal for not supervising the teachers properly. They would attack the police for not stopping the taunts. Finally, they would turn to the local government for not administering the schools appropriately–and settle for subsidies to the local buraku (Aoki, 1998:143). (70-71)

This composite picture fails on numerous points, including (crucially) the fact that the cited reference does not actually mention any demand for an apology targeting the teacher or principal or an attack on the police. It is nothing but a phantasy image conjured up by JMR.53

JMR then gives another, early example of a kyūdan. Only a few months after the Suiheisha was established, seven members of the Nara branch of the Suiheisha were sentenced for public disturbance after protesting a local high school principal’s condonement of discrimination. JMR references the incident as follows:

In May of 1922, the Suiheisha would hold the first of its Nara denunciations (kyudan) in the village of Taisho (Naimu sho 1922:62). In 1889, neighboring villages had rejected mergers with Taisho, and to the BLL “the reason was extremely simple.” They had refused because Taisho was a buraku. Never mind that in one of the other buraku villages that would merge, a substantial number of households were delinquent in their taxes (Naramoto, 1955:66–67). Forty years later, the perceived insult remained raw. As the official BLL publishing house would write in 2009 (Asaji et al., 2009:43; see also Amagasaki, 1988:229), “it was because the burakumin were nakedly excluded” through these mergers in 1889 that they “rose up in a movement to improve the buraku.” (42)

Kimura Kyōtarō, a well-known Suiheisha activist, was involved in the 1922 Taishō village protest mentioned by JMR. Later in life, Kimura recorded his version of what transpired during the protest, in the form of a published letter to his son who had just turned 20 years of age. After mentioning to his son that he had spent his twentieth birthday in prison, he went on to explain the reason why:

The higher elementary school in Taishō village was opened in April of 1920 and on May 15 of 1922 students who were commuting to the school from Kobayashi buraku, while doing their rostered school cleaning duties, were discriminated against by a student by the name of Urisaka Shigeru from Narabara district. At the time, I was the head of Kobayashi Youth Group, as well as Nara district committee member for the Suiheisha established at Kyoto Okazaki Public Hall on March 3. Without delay, I, along with Nakashima Tōsaku and Nishiguchi Montarō (a former Nara prefectural politician), protested at the school which had determined the facts of the case from the perpetrator of the discrimination, but the principal Matsushima Noburu simply avoided responsibility by saying that “it had been properly investigated. That evening, a general assembly meeting of Kobayashi ward was convened and after consultation the following three articles were decided: (1) abolition of discriminatory treatment; (2) resignation of the responsible teacher; and (3) removal of Urisaka Shigeru. The next day (the 16th), about three hundred people, with the banner of the Youth Group at the front, sounded trumpets and proceeded in a demonstration march to Taishō School, where we handed our protest letter to the principal. However, waiting in the principal’s office was village official Tsuchiya Yoshio, who was also a committee member for academic affairs and mayor of Narabara where Urisaka Shigeru was from. He abused us by saying “did you come here to threaten us?”, whereupon he was pushed out of the room and set upon by several demonstrators. Principal Matsushima and Chief Guidance Officer Murai, who tried to intervene, were also struck and had their clothes torn. We stopped the violence, sounding trumpets to reassemble, and departed the school. Thereafter, we received a report that Narabara sounded the district bell, assembled ward residents, and intended to descend upon Kobayashi. We gathered in the temple grounds, evacuated women and children, and made bamboo spears just in case. We started a bonfire on the outskirts of the village at a strategic location and waited and watched the whole night, but not one resident from Narabara showed their face.54

Kimura recounts that ultimately several hundred police were mobilized. Eventually representatives from Kobayashi (including Kimura) went to the police station to make statements, but were themselves charged with rioting. Kimura, from the evening of May 19, was jailed for 70 days.

This letter shows that anyone reading JMR’s caricature of kyūdan, and especially his comments about the Taishō village case, would come away with a completely lopsided view. Buraku discrimination could certainly occur between individuals, but it also took place between entire communities with long histories, vastly different resources, and uneven institutional access and power. Buraku communities became connected across regions through the Suiheisha movement, as well as a range of other local organizations such as youth groups, to better protect themselves from local abuses. Far from reaping vast rewards, moreover, such activism came at a significant cost, including loss of freedom and income. While Kimura’s account must be treated with the same degree of caution as any other primary source, it should be read alongside the government records JMR purports to use, as well as the writings of later historians based on their research. Failing to utilize such sources when narrating the nature of core historical events is to distort people and their actions, and in the case of JMR’s article, impugn their motivations. It is, in short, to defame and slight Burakumin and their struggles for equal treatment.

Indeed it is strange that while impugning the motivations of Burakumin in their efforts to create an effective organization, the article does not engage in a concrete discussion of money, including government funding. Even prior to the establishment of the Suiheisha, the Japanese national government had in 1920 already established a budget for “local improvements”–a clear acknowledgement of a need to enhance the standard of living of people in Buraku communities. The local improvements budget that year stood at 50,000 yen and was intended to identify problems within Buraku communities and to work to their overall “improvement” (tokushu buraku kaizen).55 The 1921 budget was almost three times as high (145,860 yen), and national expenditures for that purpose thereafter continued to rise, reaching a high of 2,370,000 yen in 1933, a figure that came to about 0.6% of the total annual national budget for that year.56 Such spending certainly reflected official apprehension about Buraku activism and what it might spell for national cohesion and social stability if left unchecked. But at the same time, it was needed and used to target problems in Buraku communities and build community centers (rinpokan) and other communal facilities.57

The claim that Burakumin are basically a product of their own making, creating a fake history from a Marxist toolkit for identity politics, is a political argument that distorts Buraku history in an attempt to absolve Japanese society of responsibility for its treatment of a historical minority. Building on the “poor peasant thesis,” JMR claims that Burakumin were not historical outcastes, and even the ones that were did not experience discrimination in the way people say they did. Burakumin, according to the author, created a fictional identity for economic and political advantage, and in fact invited the brutal observations and treatment they received. The author does not concern himself with the socioeconomic realities of Burakumin communities, or the legal and political frameworks that continued to determine their existence and treatment in the modern period. He simply manipulates data and the writings of other scholars to lay the blame for what has been called “Buraku discrimination” at the feet of the communities themselves. The author’s self-construction argument aims to promote the idea that Burakumin added to the dysfunctionality of Japanese society and that there is no legitimate basis for their existence as an organized group. A troubling elitist politics drives this narrative and interpretation while masquerading as an objective accounting of the past.

3. The “State-Enabled Dysfunctional Interest Group” Argument

Throughout, JMR casts aspersions on Burakumin character and motivations.58 The author sees Burakumin as people with strong links to criminality and criminal organizations and claims that extortion is a common motivation of members of their communities, if not the primary function of Buraku organizations. Linked to this argument is the evaluation of postwar government subsidies for Buraku areas as a wasteful scam for Burakumin to pilfer money (3; 4; 30). This distaste for government subsidies may be seen as deriving from JMR’s adherence to the Chicago School of economics (from which the field of Law and Economics derived). But when placed in the context of Burakumin history, this argument willfully ignores the fact that modern Buraku history is also the history of a liberation movement attempting to make material along with other advances in order to combat problems specific to the histories of those communities. As noted above, JMR mischaracterizes the nature of Buraku demands in the prewar period and fails to explain the context in which violence and conflict on occasion underpinned the actions of individual actors. The overall picture the author paints is built upon assertions and not rooted in any kind of legitimate scholarly investigation. This too may be considered symptomatic of the Chicago School approach, in which, as two astute critics have noted, “The data is simply dragooned into the argument to provide support for a preconceived result.”59

While perhaps not as explicit in this paper as in some of his other works, JMR’s argument about incentives or disincentives to antisocial behavior is also driven by game theory assumptions. However, he uses this theory as an excuse to completely rewrite Buraku history, bending historical realities out of shape and decontextualizing cherry-picked events. For the author, both prewar and postwar Japanese society are dysfunctional, and two central features of that dysfunctionality are the very existence of Burakumin as a discrete category of existence as well as strong state support for or acquiescence to Buraku activism which is understood as “predatory” (41). He thus presents Burakumin as dysfunctional baggage in an ill-conceived and unscholarly revisionist agenda.

By deploying game theory, the author converts the Buraku liberation movement from a struggle for equity and justice to a program of calculated extortion. Dismissing the movement as “identity politics,” he calls Suiheisha and subsequent Burakumin leaders “criminal entrepreneurs” (3). While no serious scholar of Buraku history would deny the importance of what is today called identity politics in the formation and development of the modern Buraku liberation movement, to deliberately avoid acknowledging that modern Buraku history is at heart a liberation movement that attempts to make various material advances in order to combat particular kinds of problems specific to the histories of those communities is to grossly misrepresent Buraku experience and a vast historical record.

An understanding of Buraku activism as a liberation movement is crucial for interpreting the nature of the violence and conflict that occasionally accompanied the actions of participants in this movement. Asaji Takeshi and Hirooka Kiyonobu, in their critique of JMR’s article in this issue, remind us of the importance of the topic: “[W]hen popular movements for social change confront an oppressive authority they will inevitably embrace the illegal sphere. This is a latent historical problem.”60 To simply point out that Asada Zennosuke carried a pistol, or to rehash discussions of accusations about leading Suiheisha activists like Matsumoto Jiichirō’s criminal acts (70) as supposed evidence of the criminality of Burakumin, is to build an argument based on guilt by association and faulty generalization. Buraku liberation activists, moreover, have had a range of views as to what constitutes an appropriate strategy for impelling necessary change. Views that question Japanese society’s capacity for meaningful change are legitimate and must be carefully examined rather than dismissed out of hand. (Here, one could easily draw an analogy to discussions of the Black Panther Party in the United States, with which we suspect the author is at least superficially familiar.)

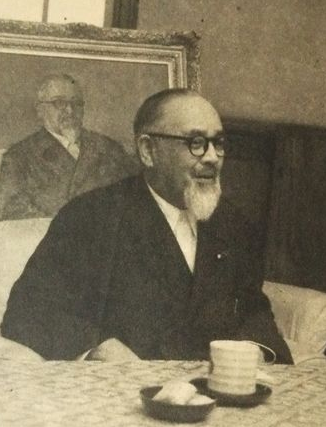

Matsumoto, Jiichirō

朝日新聞社

Source: Wikimedia Commons

For the postwar period, the author ratchets up his polemic surrounding the criminality and criminal associations of Burakumin. Readers are not informed of the (in many ways) remarkable unity of the postwar Buraku movement until the 1960s, nor do they learn how the movement was split in two different directions–on the political left and right–over the nature of how best to achieve liberation from discrimination. Missing from the author’s story are the efforts over many decades that achieved major improvements to the lives of Burakumin, including increased employment (60.6% of Buraku residents were engaged in some form of employment in 1993 against a national average of 63.9 per cent compared to 55.8% in 1967), increases in mixed residency in Buraku areas (58.7% of Dōwa area residents were non-Burakumin in 1993, up from 33.2% in 1967), increases in high school matriculation rates (Buraku high school matriculation rates were up from 30 per cent in 1963 to 91.2 cent in 1992), and so on.61 Each of these improvements was underpinned by arduous work at the local level by committed activists and other concerned parties and was helped by government funding. To fail to acknowledge these points, and to represent the Dōwa measures as a kind of state-enabled extortion by a semi-criminal organization, is to thoroughly misrepresent the postwar history of Buraku liberation.

JMR’s claims about Buraku youth entering into criminal organizations as a career path do not hold water. He argues that government measures aimed at the elimination of the Buraku problem “increased the incentives for buraku men with the lowest opportunity costs to crime to drop out of school and invest in criminal skills” (3), but as Akuzawa Mariko and Saitō Naoko demonstrate in their article in this issue, this assertion is not supported by the publicly available data. Among other things, the data suggest that the proportion of elderly residents in Buraku districts increased during the period when the “Special Measures Laws” were in effect (that is, 1969-2002), while conversely the total number of youth decreased markedly in these districts during the same period.62

Throughout, in fact, the author demonstrates what might be called a cavalier approach to statistics that renders unclear who exactly fits within the category of the “Buraku subject” and what one can reasonably conclude about them based on survey data. JMR writes of having consulted 14 “national surveys” (1) and makes claims about the size of the Buraku population in the modern period based on these surveys spanning 1868 to 1993 (11). However, an honest appraisal of the statistics used by JMR would surely conclude that they do not capture the same problem over time, something alluded to in the source materials the author uses to list his data. Despite this, JMR simply lists the number and runs with his argument on population numbers.63 Based on these statistics, and the intersection of these same statistics with other statistical clusters that speak to issues of crime, marriage, family composition, and the like, the author then makes a number of bold, one might even say outrageous, claims about the empirical realities and nature of the “Buraku” problem in modern Japan. At the same time, however, he also attempts to explain how the composition of these communities changed through outmigration or through a public recasting of problematic areas as Buraku communities, so that the actual meaning of the term Buraku cannot really be considered constant or pointing to the same kind of community, people, or problem. Perhaps aware of the pitfalls of this approach, JMR prefers simply to evade them while insisting on his a priori definitional claim: “Readers should take the [survey] numbers with caution. No one offers a precise definition of the ‘burakumin’ – or anything close. Nor could they. As the discussion below elaborates, the term has always been a loose identifier for what simply amounts to a dysfunctional under-class” (13). Moreover, as critics of his work in law and economics have observed, “Ramseyer also employs a statistical strategy that might be called the ‘mego’ approach to statistics, namely ‘my eyes glaze over’ when I attempt to work my way through the volume of statistical tests presented within one paper. The sheer volume of data and statistical tests cause any but the most determined reader to relinquish concerted attempts to examine the empirical work closely. This approach extends generally to all of Ramseyer’s work.”64

At a broader level, however, the overall picture the author paints of the Buraku Liberation League as a state-enabled semi-criminal organization is completely driven by the author’s theoretical concerns and predetermined conclusions and is not rooted in any kind of legitimate scholarly investigation. Certainly our understanding of the Buraku problem in postwar Japan could benefit from more analysis of the exact pathways of the roughly 100 billion US dollars (in today’s evaluation) provided through a series of Special Measures Laws between 1969 and 2002. Indeed the idea that such a mass outpouring of money would attract criminals to Buraku liberation organizations as well as designated Buraku areas is logical and anecdotally true in some cases. Yet the author produces no reasonable evidence to demonstrate that such corruption was systemic, or that it was anything more than the actions of a few people receiving a disproportionate amount of press coverage. What we find in the article are simply assertions based on cherry-picked examples and it is clear that the author has not engaged in any kind of research based on specific areas, communities, or cases that would enable him to properly establish his argument.

In sum, while the primary and secondary sources in both Japanese and English point overwhelmingly to a story of modern Buraku liberation that involves struggle and material progress, JMR’s article, seemingly driven by the utopic image of a “normal” Japanese society where markets are left to their own devices and the state stays out of the lives of its citizens, paints Japan’s largest minority as an artificial creation, both a form and a driver of dysfunction, and essentially criminal in nature. If there is a social failure in Japan in relation to Burakumin, the author tries to conclude, it is that people took their claims and actions seriously and permitted them to engage in predation of state finances. An article with such an argument would probably be rejected outright for review if it was dealing with India’s Dalits or another racial or ethnic minority group closer to home. To interpret Buraku history as criminal and parasitical is to both victimize the victim and demonize those who voiced legitimate claims about a particular form of injustice. It is an argument built on empirically unstable foundations and constitutes a clear retrogression in terms of understanding Burakumin and their history.

Conclusions

The technical problems with JMR’s article are clear: the author has failed to pay due attention to context, carefully scrutinize available sources, carefully weigh causal factors, and reasonably engage with existing scholarly interpretations. His commitment to a particular theoretical framework (the Chicago School and game theory) prevents him from performing the due diligence of empirical work. At the same time, he does not even discuss the theory, demonstrate its utility, discuss its applicability to the real world, or indeed acknowledge any possibility that it may require amendment or modification in light of new evidence. The lack of theoretical framing of the author’s argument is academically irresponsible in light of what is at stake for the people he writes about. The author’s muffling, silencing, and distortion of the voices of Burakumin speaks volumes about his approach to scholarship, his understanding of history, and his views on human rights. We, as scholars, cannot and should not permit the vulnerabilities of Burakumin to be glossed over and their experiences erased at the stroke of the ideologue’s pen.

It is sobering to consider that much more could be said about the academic and ethical failures of this particular article. It is also significant that some of the data used by JMR is currently subject to a court case. The Buraku Liberation League, along with several hundred plaintiffs, filed two court injunctions in 2016 in relation to online and hardcopy publication of the 1936 Zenkoku Buraku Chōsa data. JMR acknowledges obtaining and utilizing this data in a co-authored article published in 2018 (221).65 Ultimately, however, the three linked arguments of this article should be understood as a function of the author’s politics. The author’s vitriolic attack against one of Japan’s most historically exposed communities seems to be tied discursively to attacks on minorities in the United States and elsewhere. In many ways, Japan is simply a proxy battleground for these campaigns, an offshore site at a presumably safe enough distance from home to test objectionable ideas, and an opportune field where the author can have free reign for expression because of generalized cultural illiteracy about Asia and monolingualism across significant parts of the Anglophone academy and the presumption of authority that his institutional affiliation provides. Burakumin in this article have become collateral damage, their historical struggles flattened out by the author’s theoretical flights of fancy, and their image and reputation tarnished by a value orientation that is elitist, but one that also shares common ground with groups on the political right preoccupied with social and racial purity.

Notes

J. Mark Ramseyer, “On the Invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcastes in Japan,” Review of Law & Economics 16:2 (2019): 1-95.

See, for example, the four responses to JMR’s work on comfort women at Alexis Dudden, ed., “Supplement to Special Issue: Academic Integrity at Stake: The Ramseyer Article – Four Letters (Table of Contents)” in The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 19, Issue 5, Number 2, March 1, 2021. Also Jeannie Suk Gersen, “Seeking the True Story of the Comfort Women: How a Harvard professor’s dubious scholarship reignited a history of mistrust between South Korea and Japan,” New Yorker, February 25, 2021.

See the responses contained in this special issue, and Buraku Kaihō Dōmei Chuō Honbu, “Māku Ramuzaiyā ronbun ni taisuru chūo honbu kenkai,” Kaihō shinbun, April 5, 2021.; also The International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism Statement: “Problem of Ramseyer’s Article on Buraku: from the Perspective of Human Rights and Non-Discrimination,” March 8, 2021 ; and Kadooka Nobuhiko, “Hinkon naru seishin: Haabaado Dai kyōju no chingakusetsu” (parts 1-12, May-December 2020), along with a summary (February 22, 2021) and “A review of Professor Mark Ramseyer’s papers on the Buraku Issues” (March 2, 2021), all at Gojū no tenarai (blog).

J. Mark Ramseyer, “A Monitoring Theory of the Underclass: With Examples from Outcastes, Koreans, and Okinawans in Japan,” (January 24, 2019), 2.

J. Mark. Ramseyer, “Social Capital and the Problem of Opportunistic Leadership: The Example of Koreans in Japan,” European Journal of Law and Economics (2021).. For a brief discussion of the Moynihan report, see Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016), 40-41.

J. Mark Ramseyer, review of Lovesick Japan: Sex, Marriage, Romance, Law, by Mark D. West, Monumenta Nipponica 66, no. 2 (2011): 383. Accessed April 15, 2021.

Song Sang-ho. “(LEAD) Harvard Professor Ramseyer to Revise Paper on 1923 Massacre of Koreans in Japan: Cambridge Handbook Editor.” Yonhap News Agency, February 20, 2021. For another example of this anti-Korean writing, see Ramseyer, “Social Capital and the Problem of Opportunistic Leadership.”

De Gruyter Statement on Publication Ethics, (accessed April 12, 2021). Also see the COPE guidelines.

Amy Stanley, Hannah Shepherd, Sayaka Chatani, David Ambaras, and Chelsea Szendi Schieder, “‘Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War’: The Case for Retraction on Grounds of Academic Misconduct,” February 18, 2021.

JMR writes: “In fact, most burakumin are descended not from leather-workers, but from poor farmers with distinctively dysfunctional norms” (1). And again, “Instead, most burakumin trace their ancestry [to] a loose collection of unusually self-destructive poor farmers” (2). Further, “Most burakumin instead trace their ancestry to poor farmers” (38). Arising out of his claim that the majority of early modern Burakumin were poor peasants are several other additional claims: (1) discrimination of Tokugawa ancestors and modern burakumin has nothing to do with premodern ideas about ritual impurity or occupation-linked status; (2) very few kawata dealt with dead animals or worked with leather or as executioners; (3) there was a lot of social mobility between kawata and commoner settlements in the Tokugawa period, motivated by economic push and pull factors; and (4) government regulations and sumptuary edicts were issued only in the second half of the Tokugawa period and in response to kawata economic successes; therefore, discrimination against kawata cannot have been a big deal (if it existed at all, it was motivated not by contempt but by fears of kawata upward mobility).

For a concise summary of the early modern Japanese status system, see the introduction to Maren Ehlers, Give and Take: Poverty and the Status Order in Early Modern Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2018), and David Howell, Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). For pioneering work on the issue of status marginality (mibunteki shūen), see publications by Tsukada Takashi and other members of the Status Marginality Research Group such as Shirīzu kinsei no mibunteki shūen. 6 vols. (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2000).

Suzuki Ryō, for example, building on the early work of Tsukada Takashi, Hatanaka Toshiyuki and others, argued that when the early modern outcaste system was legally eliminated in 1871, new policies pertaining to land and household registration led to a continuation of many former outcaste communities’ subservient relationships to neighboring commoner communities. Suzuki Ryō, Kindai Nihon Buraku mondai kenkyū josetsu (Hyōgo: Hyōgo Buraku Mondai Kenkyūjo, 1985), 7-33.

Asao Naohiro, “Bakuhansei to Kinai no ‘kawata’ nōmin: Kawachi no kuni Saraikemura o chūshin ni,” in Asao Naohiro chosakushū, vol. 7 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2004), 4–12.

Anan Shigeyuki, “Osaka Watanabe mura kawa shōnin no kōeki nettowāku: Kyūshū wo chūshin ni,” in Kokka no shūen: tokken, nettowāku, kyōsei no hikaku shakaishi, ed. Tamura Airi, Kawana Takashi, and Uchida Hidemi (Tokyo: Tōsui Shobō, 2015), 149.

Tokyo-fu shiryōkan no nijūni. Tokyo-fu, 1872–1875. Tokyo Metropolitan Archives, E-chishirui-085 [35]; Nakao Kenji, Edo shakai to Danzaemon (Osaka: Kaihō Shuppansha, 1992), 168; John Porter, “Cattle Plague, Livestock Disposal, and the Dismantling of the Early Modern Status Order,” in Revisiting Japan’s Restoration: New Approaches to the Study of the Meiji Transformation. ed. Timothy Amos and Akiko Ishii (London: Routledge, Forthcoming).

A survey of compilations of source materials for kawata / eta / chōri villages for both eastern and western Japan turns up ample evidence that skins or secondary products linked to leatherwork or the labor and skills required to undertake the work were being sourced from these communities. In eastern Japan, see, for example, Saitama-ken Dōwa Kyōiku Kenkyū Kyōgikai, ed., Suzuki-ke monjo, 5 vols. (Urawa: Saitama-ken Dōwa Kyōiku Kenkyū Kyōgikai, 1977-78). For western Japan, see, for example, Harima no kuni Kawata-mura Monjo Kenkyūkai, ed. Harima no kuni kawata-mura monjo (Kyoto: Buraku Mondai Kenkyūjo, 1969).

A helpful discussion of pollution as an “elastic idiom” in early modern Japan can be found in Herman Ooms, Tokugawa Village Practice: Class, Status, Power, Law (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 272-278. Ooms emphasizes that the idea of pollution could be played up or down in the context of social and political struggles.

See Ooms, ibid.; also Timothy D. Amos, Caste in Early Modern Japan: Danzaemon and the Edo Outcaste Order (London: Routledge, 2020), 71-86. Obviously we need to be careful about what we mean by the term “discrimination,” and distinguish between the changing meanings of how “discrimination” is defined across history. See, for example, Timothy D. Amos, Embodying Difference: The Making of Burakumin in Modern Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2011), 76-82; 97-100.

Minegishi Kentarō, “Kegare kannen to Buraku sabetsu (jō): sono fukabunsei to kegare kannen no itchi,” Buraku mondai kenkyū 161 (2002): 75-96; Minegishi Kentarō, “Kegare kannen to Buraku sabetsu (ge): sono fukabunsei to kegare kannen no itchi,” Buraku mondai kenkyū 162 (2002): 97-119.

The following 21-volume series includes many examples of such policies and practices. Harada Tomohiko, ed., Hennen sabetsushi shiryō shūsei (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1983-1995).

Nakao Shunpaku, Shūkyō to Buraku sabetsu: Sendara no kōsatsu (Tokyo: Kashiwa Shobō, 1982), 288; Harada Tomohiko, Sabetsu to Buraku: shūkyō to Buraku sabetsu wo megutte (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1984), 12-13.

“Dannaiki mibun hikiage ikken,” in Nihon shomin seikatsu shiryō shūsei, ed. Harada Tomohiko and Kobayashi Hiroshi, vol. 14 (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1971), 477.

Okuma Tetsuo, “Gunma,” in Higashi Nihon Burakushi: Kantō-hen, ed. Higashi Nihon Buraku Kaihō Kenkyūjo, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Gendai Shokan, 2017), 246-247.

Hatanaka Toshiyuki, “‘Etagari’ ni tsuite: yōgo toshite no saikentō,” Ritsumeikan keizaigaku 57, no. 1 (2008): 60.

See, for example, Joseph D. Hankins, Working Skin: Making Leather, Making a Multicultural Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Christopher Bondy, Voice, Silence, and Self: Negotiations of Buraku Identity in Contemporary Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015).

Mitani Hideji, Hi no kusari: Wajima Tametarō-den (Tokyo: Sōdo Bunka, 1985), 81. The claim in question is “burakumin averaged 30 to 40% of the rioters” and is cited as Mitani 82 in Ramseyer (84). However, the sentence develops thoughts and contexts from the previous page, and the term JMR translates as rioters, kenkyo-sha, actually means those rounded up by the police. The author’s first name is misspelled as Hideshi in JMR’s bibliography, which also lacks the subtitle. It should be noted that no sources for this estimate of 30-40% are listed. The full sentence explains why so many Burakumin participated in the so-called Rice Riots. It asserts that in places with many Buraku like Kyoto, Ōsaka, Hyōgo and Nara, upwards of 30%, and as much as 40% [of those rounded up] were Burakumin, and that moreover, of the thirty-five women who were rounded up, thirty-four were women from Buraku (82), a propensity linked a page earlier to actual suffering. The prize-winning portrait of Wajima combines “historico-social” (430) background from Mitani with the oral histories he had long heard from Wajima. About his method, Mitani writes: “the shifts in thinking and so on of the people who appear had to be filled out (補完する) based on the laws of human psychology” (430). In short, even apart from whether the narrator is correct about the percentage, this is a highly interpretive work; moreover, it is not clear whether it is the reminiscing subject Wajima or the creative narrator Mitani who put forth the figure of “upwards of 30%, and as much as 40%,” and which, if any, police report this may have come from. This figure cannot be extracted as a fact, in order to bolster a sequence of related claims, without even knowing the bare minimum of who made this claim and how they arrived at this judgment. For a discussion of Burakumin involvement in the Rice Riots, government responses, and efforts to depict the Burakumin as especially vengeful and violent, see Jeffrey Paul Bayliss, On the Margins of Empire: Buraku and Korean Identity in Prewar and Wartime Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2013), 134-40. On p. 136, Bayliss writes: “The police responded as well by cracking down on disturbances in buraku areas with much greater severity than they applied elsewhere; as a result, roughly 10 percent of those arrested for involvement in the riots were burakumin, at a time when the minority comprised barely 2 percent of the total population of Japan.”

See Toriyama Hiroshi, “Problems with the References to Historical Documents in J. M. Ramseyer, “On the Invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku outcastes in Japan” in this journal.

“Dannaiki mibun hikiage ikken,” 477; Saitama-ken Dōwa Kyōiku Kenkyū Kyōgikai, ed., Suzuki-ke monjo, vol. 1 (Urawa: Saitama-Ken Dōwa Kyōiku Kenkyū Kyōgikai, 1977), 64.

Ian Neary, “Burakumin in Contemporary Japan,” in Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity, ed. Michael Weiner (New York, Routledge: 2009), 73-74; David Chapman, “Managing ‘Strangers’ and ‘Undecidables’: Population Registration in Meiji Japan,” in Japan’s Household Registration System and Citizenship: Koseki Identification and Documentation, eds. David Chapman and Karl Jakob Krogess (London: Routledge, 2014), 98.

“Etsuran kinshi no jinshin koseki? Netto ni sabetsuteki hyōgen, Hōmukyoku ga

shuppinsha kara kaishū,” Chūnichi shinbun, April 4, 2021.

Noah McCormack, “Buraku Immigration in the Meiji Era – Other Ways to Become

‘Japanese’,” East Asian History, no. 23 (June 2002): 98.

Ibid., 107. See also Jun Uchida, “From Island Nation to Oceanic Empire: A Vision of Japanese Expansion from the Periphery,” The Journal of Japanese Studies 42, no. 1 (2016): 57–90. Uchida discusses an 1886 proposal to encourage emigration of Burakumin to the Philippines, where they could act as agents of Japanese imperial expansion.