The Japanese version of this article follows the English translation.日本語版が英語版の後に掲載されています。

In March 2020, we wrote this paper in response to discussion paper No.964, “On The Invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcaste in Japan”, June 20, 2018, written by J. Mark Ramseyer (JMR), which was released on the website of Harvard’s John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics, and Business.

We understand that after that a new version was published in the Review of Law and Economics, Volume 16 Issue 2, 2020, with the same title, However, we regard these two as essentially similar, so we are releasing this report critical of the former version.

Introduction

There is a wide range of problematic issues in this work by JMR. In particular, the method can only be described as using strained interpretations of references to previous research and erroneous use of proper nouns. However we will focus here on key points of his historical research, especially modern history and the Suiheisha (水平社).

Problems with Ramseyer’s assertions about modern Buraku history

Overall, concerning the period from the Meiji restoration up to the formation of the Suiheisha, JMR argues the case for the impoverishment of Buraku communities and tries to demonstrate their alleged criminal tendencies (25-30). He says almost nothing about the so-called Buraku Improvement Movement or the improvement projects. But historically, contrary to the view of Buraku people as criminals, the Buraku Improvement Movement started from inside Buraku communities, and its historical experiences prepared for the founding of Suiheisha.

JMR produces thirteen tables using data from a variety of different sources including, for example, “Statistics about Buraku” published in the collection series of historical materials, Nihon Shomin Seikatsu Shiryō Shūsei (日本庶民生活史料集成, Data on the Lives of Japan’s Common People, which he translates as Collection of Materials Regarding the Japanese Poor, vol.25, named Buraku 2, and other reports produced by the pre-war Naimushō (内務省, Home Ministry). However his comments and interpretations of them are outrageous. To take one example: Table 9 includes statistics on rates of illegitimacy, divorce and infant mortality (67). First he does not consider the possibility that these statistics represent the response to discrimination and that there are surely problems in equating rates of illegitimacy with levels of criminality (29). Other researchers who have concerned themselves with the reproduction of these historical sources including, for example, Akisada Yoshikazu (秋定嘉和) who wrote the introduction for this collection of historical materials, have drawn attention to the discriminatory nature of the material. The way he pays no attention to this and relies on the statistics alone is an affront to the history of research in this field and suggests that there are problems with his approach which precede his statistical processing.

The analysis of the crime statistics suffers from the same problems. In spite of the need to question the approach taken in the gathering of police statistics at the time, which linked Burakumin to crime, there are serious problems with his uncritical use of the data from which he deduces “statistically significant relationships”. Relying on the views of the police, he argues “burakumin were leading the riots” (27) . This was an example of media manipulation by the government. After the 1918 Komesōdō (米騒動, Rice Riots), the police arrested many Buraku people. It is well known as a typical case of how the dominant power divided people using discrimination.

Incidentally in the course of his analysis he notes that Suiheisha groups often formed in relatively well-off Buraku communities. He considers this ‘curious’ but this is only because his hypothesis depends on the mistaken premise that the Suiheisha movement was created on the basis of a Burakumin identity that was fabricated by ‘Bolsheviks’.

Problems with his account of the Suiheisha

His assertions about the fabrication of ‘identity politics’

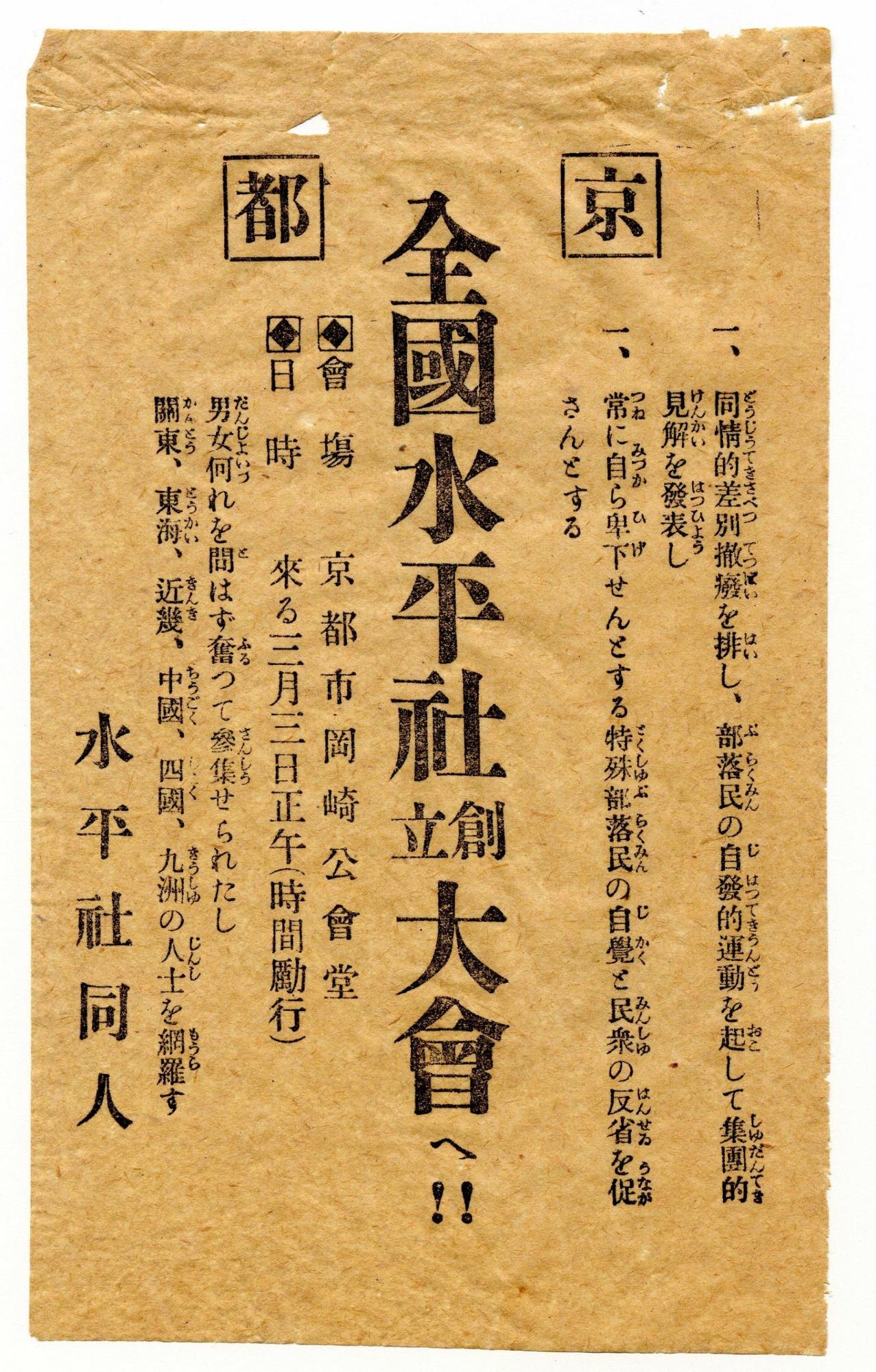

He argues that the National Suiheisha was a product of identity politics based on “a new and largely fictitious group identity” (30). Here he is possibly pointing to the “appeal to Tokushu Burakumin” which is contained in the Declaration of the Suiheisha adopted by the Founding conference in 1922. However, he does not demonstrate the basis for his conclusions and the evaluation itself is unreasonable.

The young men from Buraku communities who were central to founding the Suiheisha had a variety of personal histories, and were united through their shared experience of discrimination. Many had embraced the new thinking and literature that arrived in Japan during the 1910s and not only communist thought. They brought these ideas together in the Declaration of the Founding Conference of March 1922. Incidentally, it is strange that JMR does not refer to the essay “On the Liberation of the Special Buraku” by Sano Manabu (佐野学) a member of the Japan Communist Party (JCP, founded July 1922) which is well known to have had a profound influence on Saikō Mankichi (西光万吉) and others in the founding group. Anyway, the idea that the National Suiheisha was based on an ideology that communists injected from outside the Buraku communities not only runs counter to the historical evidence but denies agency to the vast body from the Buraku community who gathered at the founding of the Suiheisha demanding liberation from discrimination. This cannot be overlooked.

Unreasonable evaluation of the activities of the Suiheisha

JMR claims that kyūdan (糺弾) activity ranged from simple acts of violence but shaded into overt extortion (34). Kyūdan refers to the protest activities by Suiheisha members against instances of discrimination and at times incidents of kyūdan provoked state repression. It has to be admitted that there were aspects of kyūdan strategy which were immature and unskilled but the way the police regarded incidents of kyūdan as criminal activity should be regarded as an aspect of police repression linked to the “maintenance of public order”. More than anything we should note that denunciation of discrimination was regarded as legitimate by many including for example Count Arima Yoriyasu (有馬頼寧), president of the Dōaikai (同愛会), the moderate organisation formed alongside the Suiheisha that for a time was willing to work with it. This is something that JMR ignores.

JMR does not mention that within the National Suiheisha there were serious debates about strategy. It is true that not a few Suiheisha activists were linked to and were even members of the JCP, whose existence at the time was illegal. But if, as JMR claims, the Bolsheviks lost influence after the first few years, how are we to explain the rivalry between the anarchist and Bolshevik factions within the Suiheisha or the “dissolution debate” of the early 1930s?

Matsumoto Jiichirō (松本治一郎) played an iconic role within the Suiheisha in its middle and later periods. JMR regards him as the representative of a group of entrepreneurs who formed an “apolitical, opportunistic criminal cohort which highjacked the Suiheisha in pursuit of personal profit” (33). There are several problems with this interpretation. Matsumoto Jiichirō was considered a social democrat within the Suiheisha and also was a politician who was elected to the Diet in 1936 and affiliated with the Social Masses Party. The allegation that he was a criminal is made in the context of the Tokugawa Iesato Assassination Attempt Incident (1924) and the Fukuoka Regiment Bombing Incident (1926-7). However the accepted explanation of both of these incidents is that they were attempts by the authorities to suppress the National Suiheisha and were examples of media manipulation. (Incidentally we might remember that when popular movements for social change confront an oppressive authority they will inevitably be accused of acting illegally. This is a latent historical problem.)

Problems of relying on official data

JMR’s hostility towards the Suiheisha reflects the views of the authorities of that time. In particular he places great reliance on reports by Hasegawa Nei (長谷川寧) (Hasegawa, Nei. Suiheiundō narabi ni kore ni kansuru hanzai no kenkyū [A Study of the Leveler Movement and Associated Crimes, 水平運動並に之に関する犯罪の研究]. Shihō kenkyū, 5(4). (司法研究報告書輯, 第5輯4, 司法省調査課) 1927 (31-35 ff.). Hasegawa, a public prosecutor, viewed the Suiheisha as a criminal group and JMR simply adopts this view.

Apart from this he relies on such sources as the Kyoto prefecture police, such as Kyōtofu keisatsu bu (京都府警察部), Suiheisha Jōsei Ippan [Some Thoughts on the Circumstances of the Suiheisha, 水平社情勢一班] 1924 (35). These archived official resources were uncovered thanks to the efforts of many scholars over the years but at the same time the discovery of new material about the Suiheisha movement has proceeded apace. JMR’s approach, which uncritically uses only official sources, is not the kind of historical research that can be evaluated highly.

In addition although he uses such materials as the unpublished survey report Zenkoku Buraku Chōsa [全国部落調査, national survey of Buraku] compiled by the Chūō Yūwa Jigyō Kyōkai (中央融和事業協会, Central Association for Yūwa Projects) (53-72, table 1-13), it seems to be employed without understanding the nature of the Yūwa projects or the historical facts related to the institution, Chūō Yūwa Jigyō Kyōkai. Further, we do not understand the basis for his assertion that the Suiheisha used violent kyūdan activity to “extort” economic benefits from local governments. The historical facts are that Yūwa Projects were part of a national policy to adopt conciliatory measures towards the Burakumin community so as to undercut the influence of the Suiheisha movement. It was in this context that the government provided a budget for the Yūwa Projects controlled through the Chūō Yūwa Jigyō Kyōkai. We find it strange that he does not mention this institution.

Conclusion

JMR employs a negative approach to the studies of Buraku history, criticising it as having proceeded on the basis of a Marxist historical perspective (31-32). However, if he is going to question established interpretations and evaluations of events whose nature has been clarified in recent research he must demonstrate specifically, case by case, how existing interpretations of historical data are mistaken. He does not do this. He does not use bibliographic sources honestly. He repudiates the history of previous research on the Buraku issue on the basis of his preconceptions. In addition he sticks tenaciously to an aggressive account which shows contempt for Buraku people and historical evaluations of the Buraku liberation movement. Concerning social problems and social movements connected to human rights, he intentionally emphasises partial examples and then applies them to explain the whole. This is not only academically dishonest but suggests dubious intentions. We are afraid that his approach will create openings for the application of the methods of historical revisionism to distort the history of the Buraku problem.

March 13, 2021.

M.Ramseyer の近代部落史および水平社理解の問題点

以下に示したわれわれの見解は、Harvard John M. Olin Center for Law, Economics, and Businessウェブサイトにおいて”On The Invention of Identity Politics: The Buraku Outcaste in Japan”, Draft of June 20, 2018として公開されているディスカッションペーパーNo.964にたいする批判を準備するために2020年3月に作成されたものである。その後、同題の論文がReview of Law and Economics誌Volume 16 Issue 2(2020年)に掲載されていることを知ったが、骨子において変わりはないものと考え、旧稿への批判をそのまま公開することとした。(2021年3月13日追記)

2020 年 3 月 3 日 朝治武、廣岡浄進

はじめに

M. Ramseyer(以下、JMR)のディスカッションペーパーについては、先行研究の文脈を無視した引用参照や固有名詞の誤記など問題点が多岐にわたる。しかしながら、近現代史および水平運動史にかかわる歴史研究として看過できない点に絞って記す。

近代部落史にかかわる記述の主な問題点

明治維新から全国水平社創立までの期間を一括して、筆者は、25 頁から 30 頁にかけて、部落の貧困化と犯罪傾向を論証しようとする。いわゆる部落改善運動や改善事業への言及はほとんどない。だが、部落を犯罪と結びつける同時代の視線に対抗して、自主的な部落改善運動が進められ、その歴史的な経験 が水平社創立につながる。

同氏は史料集『日本庶民生活史料集成』第25巻(部落2)所収の「部落に関する諸統計」や、戦前の内務省の統計書などから、それぞれ性格の異なる様々な統計を利用して13の表を作成している(53-72 頁)。それらは、史料批判も解釈も論外である。例えば、表9Aは婚外子(illegitimacy)、離婚、死産の比率をあげているが(67頁)、これが差別の結果として出てくる数字である可能性を検討していないのみならず、これを犯罪と同列視している論者の認識が問われるところである(29頁)。同書でその史料解題を執筆した秋定嘉和氏をはじめとして、これらの史料の復刻に関わった研究者たちはおしなべて史料の差別性への留意を促している。にもかかわらず、無批判にこれらの統計書に信頼を置く研究手法は、研究史への冒瀆であり、統計処理以前の問題を示唆する。

犯罪統計の検討も同断であり、そもそも部落民を犯罪と結びつける同時代の警察統計の視線が問われなければならないところであるにもかかわらず、批判的検討をしないまま「統計的に有意な関連」を推測する同氏の見識にこそ大きな問題があると言わざるをえない。警察資料を無批判に信用する同氏は米騒動 は部落民が主導したと主張するが(27頁)、政府による報道操作の好例であり、米騒動において部落民を集中的に検挙した刑事弾圧は、差別を利用した民衆の分断支配の典型例としてひろく知られている。

ちなみに同氏は統計分析から、水平社が比較的に富裕な部落で組織されていると論じて、それを奇妙であると評価しているが、これは、そもそもの同氏の仮説、つまり水平社がボルシェビキに捏造されたアイデンティティによって立ち上げられた運動であるという前提が間違っているのである。

水平社にかかわる記述の主な問題点

(1)アイデンティティ・ポリティクスのでっち上げだとする主張をめぐって

同氏は、全国水平社がアイデンティティ・ポリティクスの産物であり、「新たな、そして大部分架空の、集団的人格」(30 頁)を創出したと主張する。おそらくこれは創立大会宣言における「特殊部落民」という呼びかけを指しているのであろう。しかし、その評価の根拠は示されていないのみならず、評価そのものが不当である。

また、水平社の創立には、様々な生い立ちをもった部落青年が中心になったが、その被差別の経験の共有によって団結した。共産主義思想のみならず、第一次大戦後の戦間期情況における新思想や文学などを積極的にとりこみつつ、自分たちの言葉にして創立大会宣言にまとめている。ちなみに佐野学の論考「特殊部落民解放論」が西光万吉らに強い刺戟を与えたこと、佐野が水平社創立後の1922年7月に第一次共産党が結成されると党員になっていることはよく知られているが、不思議なことに同氏はこの論考には言及していない。いずれにせよ、共産主義者が外部から注入したイデオロギーによって全国水平社が捏造されたというような評価は、明らかに歴史の事実に反しているのみならず、差別からの解放を願って水平社創立に結集した多くの部落民の主体性を否定することでもあり、この点からも看過できない。

(2)全国水平社の活動に関わる評価の不当さ

同氏は、水平社の糺弾について、最初から「暴力」を伴っており、それのみならず単純な「経済的ゆすり」あるいは「強要」の影がさしていたと述べる(34頁)。糾弾とは、現実の部落差別にたいして水平社が提起した抗議行動である。糺弾は、ときとして、国家権力による弾圧をうけた。実際の糺弾には手法が未熟であったものもあるが、糺弾に関わるいくつかの刑事事件は、治安維持の弾圧としての側面が同時に検討されるべきである。なによりも、糺弾が当時の社会において正当性を認められていたからこそ、たとえば同愛会という、水平社と併存しつつ穏健な路線を取った融和団体を主宰した有馬頼寧が率先して肯定的に応答したという情況があることを、同氏は無視している。

全国水平社が、その内部で路線をめぐって深刻な論争を展開していたことにも同氏は言及しない。水平社の少なからぬ活動家が当時非合法であった日本共産党に加入したり関わりを持ったことは事実であるが、同氏の言うようにボルシェビキが影響力を失ったのなら、いったい、アナ・ボル対立や1930年代前半の水平社解消論を、どのように説明するのであろうか。

さらに、全国水平社の中期から後半期を象徴する松本治一郎を、水平社を私的な利益追求のために乗っ取った非政治的な(apolitical)日和見主義者(opportunists)の犯罪集団(criminal cohort)である起業家(entrepreneurs)の代表格だとする評価は(33頁)、二重三重に問題を抱えている。松本は全水では社民派として評価され、社会大衆党に所属して1936年からは衆議院議員を務めていた政治家でもある。松本が犯罪者だとする文脈で、徳川家達暗殺未遂事件(1924年)や福岡連隊爆破未遂事件(1926-27年)などを持ち出されているが、これらは全国水平社への権力弾圧であったという評価が定説であり、この点は印象操作に思われる。(ちなみに、社会変革のための民衆の運動が、圧倒的な権力に対峙するときに非合法の領域を抱えこむことがあるという歴史への理解に関わる問題が、ここには潜んでいるようにも思われる。)

(3)官憲資料に依拠する方法の問題

水平社を敵視しているように読める同氏の記述は、同時代の統治の視点をなぞっている。とりわけ長谷川寧「水平運動並に之に関する犯罪の研究」(『司法研究』司法省調査課第5輯、1927年12月)を高く評価しているが(31-35頁ほか)、長谷川が検事として、基本的に水平運動を犯罪視する立場で執筆していることについての史料批判が、同氏の論には見られない。

この外にも主として依拠しているのは、たとえば京都府警察部『水平運動の情勢』(1924年)などの官憲史料である(35頁)。これらの官憲史料は、たしかに多年の関係者の努力によって発掘されてきたものであるが、水平運動史料の発掘も進んでいる研究状況において、官憲史料を無批判に引き写す同氏の態度は、歴史研究として評価できる水準にはない。

なお、非公刊の中央融和事業協会編『全国部落調査』をはじめとする調査資料について(pp.53-72, table1-13)、融和事業の性格や中央融和事業協会の設置に関わる事実関係を押さえずに利用しているようである。水平社が糺弾を通じて地方行政から経済的利益を得たという同氏の主張の根拠もわからないが、歴史事実として、融和運動の政策目的は部落民を懐柔する国家政策であり、水平社運動の影響力を減退させることであった。そのために政府は融和運動に予算を組み、中央融和事業協会を通じて指導した。だから史料批判の観点からもJMR(ラムザイヤー)がこの機関に言及しないことは奇妙である。

総じて

同氏は、部落史研究について、全体としてマルクス主義的歴史観に基づく立場から進められてきたと批判することで、否定的にとらえているようである(31-32頁)。しかし、先行研究によって明らかにされている事実、それらに関わって定着してきた解釈や評価を覆すのであれば、個別具体的に、どのような歴史事実について誤った解釈がされてきたのかを論証すべきであろう。ところが同氏は先入観から研究史を否定して誠実に参照せず、ひいては部落民や部落解放運動の歴史的評価をおとしめる攻撃的な記述に執着している。人権に関わる社会問題と社会運動をめぐって部分的な事例をことさらに強調して全体の解釈にあてはめる同氏の姿勢は、学問的に不誠実なだけでなく、その意図を疑うものであり、歴史修正主義の方法が部落問題に関わって採用されていると危惧せざるをえない。