Abstract: This article is the second in a two part-series. Part 1 introduced Katō Kōko as the pivotal figure behind the World Heritage inscription process and the controversial historical narratives of “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.” Using Hashima Island as an example, part 1 criticised Katō’s omission of the history of Korean and other forced labor, and discussed the significance of Katō’s historical revisionism in the Industrial Heritage Information Centre in Tokyo. Part 2 explores Katō’s leading roles in several heritage related bodies in Japan. This allowed her to present historical evidence selectively and to interpret it to support her celebratory narrative of the Japanese industrial revolution while denying the relevant history of foreign forced labor. Her official roles were critical in creating platforms for neo-nationalism that legitimate radical historical revisionism. Katō’s cooperation with UNESCO is demonstrably dishonest and she should be removed from her heritage related roles in order for Japan to honour its commitment at the time of World Heritage inscription to acknowledge the history of Koreans and others who were forced to work at these sites during wartime.

Keywords: Japan World Heritage, Korean forced labor, Meiji industrialization, Tokyo Industrial Heritage Information Centre, Hashima/ Gunkanjima, Kato Koko, 加藤康子

Katō Kōko takes control of Japan’s Industrial Revolution World Heritage planning with Abe’s blessing

Japan’s World Heritage ambitions for its historical industrial sites took a major step forward at the beginning of December 2012 when Prime Minister Abe Shinzō began his second term. Within three days he appointed Katō Kōko to take charge of Japan’s industrial heritage (“Sangyō isan yaru kara”).1 Over the ensuing decade Katō’s influence and power over Japan’s World Heritage planning increased dramatically. In 2013 Katō established the National Congress of Industrial Heritage (NCIH) and became its Executive Director. The NCIH is a General Incorporated Foundation (ippan zaidan hōjin) officially created for the purpose of preserving industrial heritage and promoting related education (kyōiku keimō katsudō).2

Katō and the NCIH backed by Prime Minister Abe were unstoppable. Not even the Japanese Agency of Cultural Affairs, which traditionally had the final say in Japan’s World Heritage nominations, could halt the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution: Iron and Steel, Shipbuilding and Coal Mining (hereafter the Meiji Industrial Sites, or the Sites). The Agency’s 2013 nomination meeting selected “Churches and Christian Sites in Nagasaki” instead, with the support of local Nagasaki prefecture governments, because the Meiji Industrial Sites were connected to history “textbook problems.”3 A few days later the Japanese Cabinet held an “expert committee” meeting that decided to overturn the Agency’s decision in favor of the Meiji Industrial Sites proposal.4 Countries are allowed to make two World Heritage nominations the same year, but one of them must be a “natural property.” This requirement meant that it was impossible to nominate both the Nagasaki churches and Meiji Industrial Sites at the same time.

The committee meeting held by the Japanese Cabinet had no historians despite the stated concerns of the Agency of Cultural Affairs, but included The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) founder Sir Neil Cossons with two other Western heritage experts and nine Japanese academics in fields related to science, engineering, architecture, and economics.5 According to Stuart B. Smith of TICCIH, Prime Minister Abe personally decided in this meeting that the Meiji Industrial Sites should be nominated instead of the sites selected by the Agency of Cultural Affairs.6 Following Abe’s decision, Katō personally compiled the 2000 page nomination document in English for submission to UNESCO.7

In the final six months leading up to the Meiji Industrial Sites’ World Heritage inscription in July 2015, Katō and the NCIH criss-crossed the globe on lobbying tours to visit the World Heritage Committee member countries. Nominated sites cannot be inscribed if a country committee member objects, and South Korea had already started its own lobbying tours to inform member countries of the wartime history related to the Meiji Industrial Sites. In 2015, the 21 World Heritage Committee Member countries were Japan, South Korea, Algeria, Colombia, Croatia, Finland, Germany, India, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Senegal, Serbia, Turkey, Qatar, and Vietnam.8 Katō and the NCIH travelled to all these countries except South Korea, Kazakhstan, and Portugal, for official explanatory meetings on the Meiji Industrial Sites. 9

Regardless of complaints from Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Katō continued to present World Heritage Committee member countries with one-sided statistical data on the wartime history of Hashima, arguing that Korean criticism was “unfair.”10 Katō stated that Korean “propaganda” instigated a “tough battle” when she referred to South Korea’s own visits to Committee member countries. In retrospect she regrets having “allowed Korea to use [Japan’s] industrial heritage for political purposes.”11 According to Katō, the truth of Koreans officially conscripted for work in Japan “should be explained to Korea and other related countries, because other countries do not know the history of Japan.”12

During the remainder of Prime Minister Abe’s second term, which ended in September 2020, Katō assumed several new leading roles in government bodies. These include Vice Chairman of the National Committee of Conservation and Management for the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution (June 2014) and Chairperson of its Interpretation Working Group (September 2014). Days before the Meiji Industrial Sites were officially inscribed as World Heritage in July 2015, Katō Kōko was made Special Advisor to the Cabinet,13 specifically in charge of industrial heritage inscription and tourism promotion.14 By obtaining key roles in relevant cooperating public and official bodies with the strong support of Prime Minister Abe and several local politicians, Katō could virtually make Japan’s industrial World Heritage planning and presentation her personal domain.15

Katō’s unprecedented control over the organization and narrative construction of the Meiji Industrial Sites after the successful World Heritage inscription was set down in official documents. As documented in the Sites’ Interpretation Strategy, the Cabinet Secretariat of Japan, working with local authorities, was tasked with the following:16

1) “Establishment of the ‘Industrial Heritage Information Centre’, Tokyo.”

2) “Consistent OUV rollout across all component parts.”

3) “Updates of the full history of each site.”

Between July 2015 and July 2019 Katō served as Special Advisor in the Cabinet Secretariat, with responsibility for Japan’s industrial heritage, making her responsible for these tasks. At the same time, Katō served as Executive Director for the NCIH which had these tasks:

1) “Information gathering related to workers, including Korean workers.”

2) “Consideration of certification programme for the interpretation of ‘Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution’.”

3) “Human resource training programmes and training manual.”

As of late 2021, Katō was still the Executive Director of the NCIH and also the managing director of the Industrial Heritage Information Centre (IHIC) since it opened in Tokyo in June 2020. With Katō in charge of planning the Centre, collecting and interpreting data for its exhibitions, and controlling training manuals and historical presentations at all relevant sites, she was free to select and revise historical narratives, denying any memories and other evidence of forced labor that might threaten the image of important stakeholders.

Annex of the Statistics Bureau and entrance to the IHIC.

From UNESCO/ICOMOS July 2021 report, pp. 38.

The National Congress of Industrial Heritage

Investigating the National Congress of Industrial Heritage (NCIH) suggests that monetary gain and forced labor denial may have been just as important as the officially stated purposes designed by Katō and other NICH board members. Katō registered the NCIH’s address at exactly the same Tokyo office as three private companies in which she and her core family members had leading roles. The Vacance Corporation, where Katō’s daughter is CEO, was established in 2015 and was registered at the NCIH’s first address. When the NCIH changed its office address in 2020, The Vacance Corporation followed by sharing the exact same office address as the NCIH within the same building again.17 The previous address of the NCIH was within a short walking distance from Katō’s Transpacific Education Network mentioned in the Panama Papers. The ability to move the NCIH office together with these private companies affiliated with Katō and her family reveals her hidden influence over the NCIH and raises important questions regarding Katō’s personal agenda.

The NCIH has received enormous amounts of money from the Japanese government, many times higher than what heritage related research institutes have received in Japan in the past.18 The NCIH is not even an official research institution, classifying itself as a private foundation. From 2016 to September 2021, the NCIH has been paid at least 1.35 billion yen including consumption tax (equivalent to over $12.2 million (US)) by the Japanese government for data collection, research, and IHIC operational costs. The NCIH’s asset size for fiscal year of 2020 was more than 720 million yen with a net worth of over 131 million yen.19 Even with such capital strength, Katō claims to be unable to find any relevant evidence of forced labor or even discrimination at the Sites during wartime.

Katō and the NCIH’s data collection focused on locating primary evidence “necessary to rebut the charges leveled by South Korea.”20 Before even starting the data collection, Katō decided, based on her own interpretation, that all Koreans who worked at the Meiji Industrial Sites during wartime did so without experiencing force or discrimination. She believed in the need to deny allegations that many workers had been “killed” (“korosareta”) at these sites (“chigau to iwanakya dame nan desu”).21 In her use of the term “killed” she uses the comparison with Nazi Germany in saying mass executions didn’t happen, as these worksites were not death camps. But she ignores the fact that these were war industry sites forcing foreign laborers to work in deadly conditions, a policy not unlike Nazi Germany’s. Katō had little reason to anticipate protest against this biased interpretation within the NCIH, because for many of its members presenting evidence of the deaths of forced laborers would conflict with the interests of companies and company groups to which they have been linked.

Comparing Table 1 and Table 2 below indicates potential conflicts of interest among members. Acknowledging victims could lead to defamation and significant lawsuits for company groups like Mitsubishi and Nippon Steel. On the other hand, successfully producing and presenting celebratory stories of these companies’ contributions to Japan’s “miraculous” modernization could greatly boost their public relations image. The NCIH’s registration documents specify that the foundation has “conducted promotion and public relations activities related to industrial heritage”22 which include sites still in operation by company groups represented by key NCIH members. These companies have benefited not only from positive public relations, but also from tax reductions. When the NCIH was founded in 2013, the Japanese government started implementing a new law reducing property tax and city planning tax by two thirds for companies operating industrial sites inscribed as World Heritage.23

Table 1 – World Heritage inscribed Meiji Industrial Sites in Kyushu where Koreans and others were forced to work

|

Site Component |

Location |

Owner |

|

Hashima Coal Mine |

Hashima Island, Nagasaki |

City of Nagasaki (Mitsubishi Materials Corporation until 2001) |

|

Takashima Coal Mine |

Takashima Island, Nagasaki |

|

|

Mitsubishi No.3 Dry Dock* |

Nagasaki Shipyard |

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries |

|

Mitsubishi Giant Cantilever Crane* |

||

|

Mitsubishi Former Pattern Shop |

||

|

Miike Coal Mine and Miike Port |

Ōmuta and Arao |

Nippon Coke and Engineering |

|

The Imperial Steel Works* |

Kita-Kyushu (Yahata) |

Nippon Steel Corporation |

*Sites still in operation

Table 2 – NCIH members with potential conflicts of interests

|

Role within the NCIH |

Name |

Previous roles in conflict with revealing forced labor history |

|

Chairman |

Kojima Yorihiko |

Started Mitsubishi Corporation career in 1965, becoming company President (2004–2010), Chairman (2010–2016), Advisor to the Board of Directors (2016–2020); Board of Directors for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (2010–2016) |

|

Honorary Chairman |

Imai Takashi* |

Military student at the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy during wartime. Started Nippon Steel Corporation career in 1952, and became company President (1993–98), Chairman (1998–2003), and Honorary Chief Board Advisor (2003–n.d.) |

|

Director (1 of 16) |

Ījima Shirō |

Head of Nagasaki Shipyard as the Director of Ship and Marine headquarter of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (n.d.–2010), Direct assistant to company President (2010–n.d.) |

|

Director (1 of 16) |

Yagi Jūjirō |

Started Nippon Steel Corporation career in 1965, serving as company Vice President and Director of Engineering (2003–2005) |

|

Councilor on Board of Trustees |

Marukawa Hiroyuki |

Former Nippon Steel Corporation employee. Head of Nippon Steels’ public relations center in 2008 |

|

Advisor |

Hayashida Hiroshi |

Advisor to Nippon Steel Engineering (subsidiary of Nippon Steel Corporation) in 2015 |

*Imai initially opposed inscribing Nippon Steel’s Imperial Steelworks in Yahata (Kyushu) as World Heritage, making the questionable claim that he was concerned that outsiders would need access to factory areas that would complicate steel production,24 but he changed his mind because he had been close to the late Katō Mutsuki and “felt like [Mutsuki] wanted him to take care of his daughter [Kōko].”25

The background of NCIH members and their responsibilities within the NCIH has not been transparent.26 For example, Chairman of the NCIH, Kojima Yorihiko who was also Chairman of the Mitsubishi Corporation when the NCIH was founded, has never been mentioned as NCIH Chairman on any of the organization’s official webpages and his name is also absent from official registration forms.27 In fact, his title as NCIH Chairman seems not to have been used publicly since a November 2017 news update on Katō’s website for Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.28 The NCIH is paid large amounts of taxpayers’ money, and it should be seen as a problem that the general public cannot even confirm who the current Chairman is. There are no historians in the NCIH, and many members are strong supporters and close friends of Abe Shinzō.29

Tokyo’s Information Centre: nationalist celebration and historical denial

Katō Kōko has been Managing Director of the IHIC since it opened in June 2020. She resigned her position as Special Advisor to the Cabinet in July 2019 so that she could continue work related to the industrial heritage sites and Korea’s “allegations of discrimination” as a “private citizen.”30 The IHIC homepage describes the Centre as the main place for promoting the interpretative strategy of the Meiji Industrial Sites for visitors. The IHIC also claims to be a research institute that collects data, interprets it, manages public relations, and disseminates information.31 The Centre was required to also fulfill Japan’s 2015 commitment to take appropriate measures for remembering the victims forced to work under hard conditions at some of the Sites, but instead it actively denies that forced labor or discrimination occurred there.32

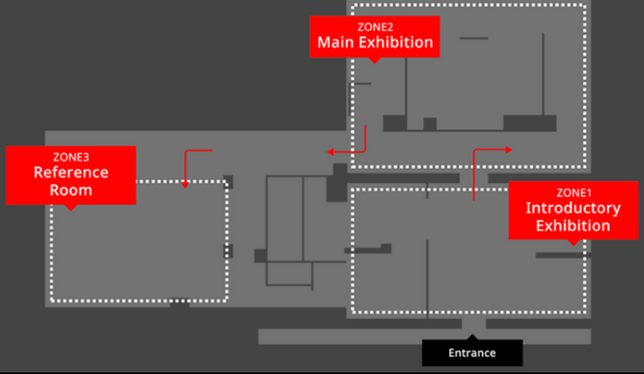

Floor plan of the IHIC with its three Zones (Gamble 2021, p. 5).

From UNESCO/ICOMOS July 2021 report, pp. 38.

Exhibition explanations are in Japanese and English, while Korean and Chinese explanations are available through a smartphone application developed by the NCIH. The Centre is divided into three zones with printed and digital information panels. The first zone introduces the Meiji Industrial Sites, the second zone explains the official history of Japan’s industrial revolution from the 1850’s to 1910, while the third zone is the “archive” section with a focus on wartime Hashima.33 The first and second zones do not include any references to Koreans or others forced to work against their will.34

Zone 1. One of two immersive multi-displays (Liquid Galaxy)

showing information on each of the 23 component sites.

From UNESCO/ICOMOS July 2021 report, pp. 43.

Both the IHIC exhibitions and visitor guides who explain the exhibits create the impression that no Koreans or Chinese were forced to work at the Meiji Industrial Sites. IHIC exhibitions are based on Katō’s primary sources, none of which were collected from outside Japan. Katō’s sources include video interviews with former Hashima residents as well as diaries, memos, and letters related to Korean workers. These materials had been “scattered throughout Japan among government agencies, private companies, individual records and collections, and so on”.35 The IHIC people who are guides for visitors, some of whom are former residents of Hashima Island, have been personally trained by Katō.36 These individuals inform visitors that forced labor did not occur at the Meiji Industrial Sites and that Koreans have lied about Hashima’s history.37 Even the ICOMOS/UNESCO mission that examined the IHIC narratives in June 2021 were told by a IHIC guide that everyone interviewed about Hashima has stated that no one was ever forced to work there, and that Koreans and Japanese were “one family sharing one island.”38

Zone 2. Table with integrated computer screens that provides information

on industrial heritage sites worldwide.

From UNESCO/ICOMOS July 2021 report, pp. 49.

The archive in zone 3 includes four edited video testimonies from the 70 testimonies collected by Katō from former residents of Hashima.39 These edited videos, as well as others, can be found on the NCIH website The Truth of Gunkanjima.40 One of the four interviewees is Suzuki Fumio, the ethnic Korean born on Hashima in 1933 who escaped as a child with his Korean family during wartime. The other three interviewees are Japanese: Matsumoto Sakae (born 1928), Inoue Hideshi (born 1929), and Tsubouchi Mitsuoki (born 1932). They knew Korean children of Korean laborers who came to Hashima before the wartime forced mobilization. All four interviewees state they have no memory of discrimination against Koreans on Hashima, which is not surprising considering they were children who had limited or no understanding of institutional racism and who would have had no interaction with wartime forced laborers.

Zone 3. Video screens, wall panels, Liquid Galaxy, book shelf, and reading area (left) and Selected photographs of testimonies (right).

From UNESCO/ICOMOS July 2021 report, pp. 52-53.

There is no description of any type of “victims” in the IHIC, and Chinese and Allied POW’s forced to work at the Sites are forgotten.41 The ICOMOS/UNESCO mission questioned Katō several times as to why the Centre does not attempt to “remember” the “victims” despite this being an important condition for approving the sites. Katō informed the mission that “the overriding aim of the IHIC was to present and celebrate the OUV of the World Heritage property in the context of industrial heritage” (emphasis added).42 The mission report describes how Katō’s responses were self-contradictory:

“[O]n the one hand, […Katō stated that] the IHIC was not set up to be a gateway to the World Heritage property but was established in response to the World Heritage Committee decision [that Japan must acknowledge those forced to work at the Sites], and on the other that the IHIC was not the place to deal with the prisoners of war who worked [there…D]isplay space within the research centre is limited and […] the content of the displays is based on [NCIH] research.”43

In other words, Katō does not see the IHIC as a place for remembrance of victims, but as a place for celebration of Japanese history and achievements. One of the first rooms visitors see in Zone 1 is the so-called “celebration room” with a “timeline leading to the inscription of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.”44 While neglecting to provide space for inclusion of the history of victims who worked at the Meiji Industrial Sites, the main narrative of the IHIC is a celebration of the technological advances of Meiji Japan, which also fails to document the countless Japanese low-skilled laborers, including Japanese convicts, treated as sub-humans by their Meiji Era managers.45 Ryoko Nakano, the only other scholar who has written about Katō Kōko in English, points out that Katō is attempting to “globalize a glorious historical narrative of Meiji Japan” that leaves no room for alternative views.46 In the words of far-right political writer and memory activist Sakurai Yoshiko, who wrote about the IHIC for the Weekly Shincho:

“[At the IHIC,] Katō has traced the footsteps of our great leaders of the Meiji Era, putting together a meticulous chronicle of their sweat, tears, joy, and insight—an evocative tale that never fails to deeply touch one’s heart.”47

‘Celebration room’ showing timeline leading to

the inscription of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.

From UNESCO/ICOMOS July 2021 report, pp. 42.

Promoting neo-nationalism as Director of the Industrial Heritage Information Centre

Katō’s friends and supporters include a large number of neo-nationalists with varying degrees of power and influence. By officially inviting them to her centre, she helps legitimize their extreme revisionism and racist views. The NCIH’s official Twitter account frequently posts pictures of Katō in the IHIC together with right-wing revisionists and war crime denialists, such as Motoya Toshio,48 Yamaoka Tetsuhide,49 Kent Gilbert,50 and the Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact.51 In addition, Katō openly gives lectures at well-known far-right institutions such as Sakurai Yoshiko’s52 Japan Institute for National Fundamentals53 and Motoya Toshio’s54 Shoheijuku academy.55

Katō Kōko allows far-right online influencers to interview her at the IHIC, including Katō Kiyotaka,56 WWUK TV,57 and Kent Gilbert.58 Discrediting Korean testimonies is a central focus of these interviews, and the large majority of viewer comments are xenophobic in nature, revealing a one-sided audience. Katō welcomes these neo-nationalist perspectives. For example, Kent Gilbert, a Japan-based American influencer who gains attention in Japan by promoting Japanese far-right rhetoric, suggested to Katō that Koreans should be grateful for Japanese colonialism, and that obligatory Japanese school trips should include the IHIC and the Yūshūkan war museum in the Yasukuni shrine complex to boost national pride.59 Untroubled that her IHIC was praised together with the highly controversial war museum at Yasukuni shrine, Katō nodded enthusiastically and commented that she liked his idea (“Ī desu ne”).

Katō also helps legitimize neo-nationalist platforms and media that the general public does not follow by appearing on far right media outlets as Director of the IHIC and being identified a previous Special Advisor to the Prime Minister. One example of her use of this type of media outlet is the far-right DHC TV news and debate program Toranomon nyūsu, described by Japanese Excite News as a “nest of the neo-nationalist cyber community.”60 When the IHIC was first discussed on Toranomon nyūsu on 1 June 2020, panel members laughed condescendingly at Korean testimonies of discrimination. A video-clip was shown of Katō antagonizing a Korean journalist by presenting pictures of Hashima witness Ku Yŏnch’ŏl, insisting his witness testimony is fabricated.61 Following this, Katō Kōko made several guest appearances as a panel member herself on Toranomon nyūsu, discussing the IHIC and dismissing forced labor history.62 Katō also guest starred on the same network’s news-centered variety talk show “Nyūsu Joshi”63 in February 2021. The narrator introduced Japan’s industrial revolution as a miracle protecting Japan from Western imperialism and claimed that modern Japanese industries can again be superior to Korean and American competition because of Japanese DNA passed on from Meiji industrialists.64

Attacking the “Straw man”

Katō Kōko’s untrustworthy way of relating to UNESCO and international stakeholders can be demonstrated with one of her proposals, noted in the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission report:

“Establish a platform for dialogue (either online or in person at the IHIC) between the Hashima Island community whose memories were recorded and are being or will be exhibited at the IHIC, with the Korean survivor of Hashima Island Yeon Cheol Koo, to consider alternative views in an open and scientific way.”65

Yeon Cheol Koo, or Ku Yŏnch’ŏl, is the Hashima witness mentioned above whose memories Katō called a fabrication on DHC TV in 2020.

According to the first chapter of Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s biography, his father found employment as a miner on Hashima several years before his family joined him on the island in 1939, living in a family apartment when Ku Yŏnch’ŏl was eight years old.66 While Ku Yŏnch’ŏl recalls witnessing abusive and discriminatory treatment of Korean and Chinese forced laborers who arrived on Hashima during wartime, he is unsure if his father experienced discrimination and abuse. Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s father never talked about his own experiences in the coal mine. Similar to ethnic Korean Suzuki Fumio, neither Ku Yŏnch’ŏl nor his father were forcibly mobilized during wartime.67 Several Korean Hashima survivors of forced labor, such as Ch’oe Changsŏp,68 Kim Hyŏngsŏk,69 and Yi Inu,70 have given testimonies of their own personal experiences to Korean media in recent years. There were seven known Korean Hashima survivors of forced labor still alive when the Meiji Industrial Sites were World Heritage inscribed.71 Why would Katō only focus on the name of one specific Hashima survivor who was a child—not a forced laborer—as an example of an alternate view of Korean wartime labor and then compare this recollection with a group of Japanese who also were only children during the wartime forced mobilization of Koreans?

Only the first two of the eleven chapters of Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s biography detail his memories from Hashima. The rest of the book describes how Ku Yŏnch’ŏl joined the communist Workers Party of Korea in 1950 and fought American soldiers as a guerrilla in South Korea before serving 20 years of a life sentence in prison.72 This is an important factor to Katō’s proposal because it distorts the portrayal of Ku Yŏnch’ŏl as a hostile and unreliable witness in Japan and South Korea, making it appear that Ku Yŏnch’ŏl is just a communist propagandist. Furthermore, details in Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s childhood memories of Hashima described in his biography such as parts of the island’s surrounding geography are factually inaccurate, making him an easier target for accusations of fabricating memories.

The former Hashima residents working with Katō who deny forced labor and all forms of discrimination against Koreans on Hashima participated in a video message produced by Katō that specifically accused Ku Yŏnch’ŏl of fabricating his memories as part of a communist plot. In the video, published online with English subtitles in 2019 entitled Who is Yeon Cheol Koo?,73 Japanese former Hashima residents laugh at seemingly inaccurate details in his biography. Matsumoto Sakae attacks Ku Yŏnch’ŏl for promoting “rubbish,”74 and it is suggested that he is a pawn in a communist agenda. The video shows footage from a “Hashima Island community” meeting attended by Katō Kōko, in which Suzuki Fumio states that they would listen sincerely to testimonies based on actual experiences, but that they “cannot respect Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s story” because they are not even sure if he ever lived on Hashima.

Katō does not mention any former forced laborers by name, but frequently names and talks about Ku Yŏnch’ŏl, turning him into a “straw man” she considers as a representation of other dubious Korean witnesses who fabricate memories as part of a political agenda. Another example from 2019 is a five-page article Katō wrote about Ku Yŏnch’ŏl in the Japanese tabloid Daily Shincho entitled “Tondemo Kankoku-jin ni Gunkanjima no moto-jūmin ga gekido, Nippon e no zōo wo aoru kōtōmukeina gendō to wa’’ (“Crazy Korean infuriates former [Hashima] residents: His preposterous conduct that stirs up anti-Japanese hatred”).75 In the article, she questions the view that Korean conscripted laborers were actually forced to live in harsh conditions and stated that “nonsensical” (detarame na) testimonies are being spread about Hashima. Katō derisively claims that while Ku Yŏnch’ŏl described Korean forced laborers as slaves, Japanese people who lived on Hashima during the war fondly remember studying, playing, and toiling at work together with their “friends from Korea.” She again suggests that Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s testimony is part of a communist conspiracy, declaring that she cannot leave Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s “allegations” alone because she believes they are “not only inaccurate, but also possibly hiding a political agenda.”

By trying to connect North Korean and “communist” agendas to Ku Yŏnch’ŏl’s memories of Hashima, and by frequently bringing up Ku Yŏnch’ŏl alone when implying Korean testimonies are generally “nonsensical,” Katō is using xenophobia to sell the notion that Koreans with memories of forced labor and discrimination on Hashima can’t be trusted. Katō’s disingenuous proposal for dialogue proves that she has worked against the spirit of the 2015 UNESCO compromise and its values of inclusion of the views of all interested parties. Katō’s actions have endangered both international relations and public trust in UNESCO, while disrespecting the dignity of victims who were forced laborers and the descendants of those victims.

Propaganda pictures by colonial authorities from 1940

showing the selection process of Koreans to be sent to Japan for forced labour.

From Seisan sarenai Shōwa – Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō no kiroku

by Hayashi Eidai (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1990) pp. 45.

Recent Developments

The World Heritage Committee of UNESCO has given Katō and Japan a new deadline of 1 December 2022 to significantly improve historical narratives of Koreans and others forced to work at the Meiji Industrial Sites. Progress appears unlikely if Katō Kōko remains in charge of these sites and how they are presented to the public. As late as August 2021, Katō posted on her website The Truth of Gunkanjima in her response to the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission report, stating that “[w]e reject the implication made at the time of listing and subsequently that Korean workers were ‘victims’ because their labor was the result of gross infringements of human rights.”76 That same month, Katō produced and uploaded the video The Residents of Hashima Island voice how much they are angry towards the 44th UNESCO Decision.77 In this video, the Chief Guide of the IHIC, Nakamura Yōichi,78 angrily states that forced labor and discrimination did not occur on Hashima, and that UNESCO must be dissolved if they continue to act as “pro-Korean.” Furthermore, Katō published an article in the right-wing political magazine Seiron that month with the rabid title “Kankoku to han-Nichi Nihonjin ni sennō sareta Yunesuko” (“UNESCO has been brainwashed by Korea and anti-Japanese Japanese people”).79

Katō Kōko’s long authority and control over Japan’s Industrial Heritage project was possible because of her extensive Japanese political and international World Heritage stakeholder networks. Katō has abused this power to construct and present historical narratives that celebrate Japan while denying the memory of Korean and other forced laborers. Her foundation that conducted research for the Meiji Industrial Sites, the NCIH, has former and present business executives connected to companies that owned, or currently own, these sites, indicating potential conflicts of interest. Hashima coal mine’s World Heritage status in particular increases tourism to the island, while relevant history is withheld from visitors. This commercial approach encourages mainstream tourists to experience the atmospheric ruins of “Battleship Island” while failing to present the full history of Hashima. Katō’s stated intention to improve historical narratives is demonstrably false.

For the sake of improving Japan-Korean relations and to give a sense of restorative justice to Korean victims of Japanese colonialism, including younger generations suffering from collective trauma, Katō Kōko should be relieved of all her roles and responsibilities relating to the Meiji Industrial Sites. If not, UNESCO will have no choice but to acknowledge that Japan has failed to honor its promise at the time of the Sites’ inscription and remove the World Heritage status from the relevant industrial sites.

Korean forced laborers driven away in colonial police trucks

while family members watch.

From Seisan sarenai Shōwa – Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō no kiroku

by Hayashi Eidai (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1990) pp. 51.

Acknowledgements

Due to global travel disruptions, visits to the IHIC and elsewhere in Japan have been impossible while doing research for this article. Descriptions and pictures of the IHIC are taken from sources cited in the article, such as the extensive July 2021 UNESCO/ICOMOS mission report. I would like to express my thanks to David Palmer for his invaluable support including advice on the presentation of arguments, suggestions for additional sources and photographs, and extensive copy-editing; Mark Selden for encouragement to write the article and for final copy-edits; Kobayashi Hisatomo of the Network for Research on Forced Labor Mobilization for advice and for sharing some of his own sources confirming the position of key members of the NCIH; Takeuchi Yasuto for his contribution of the photo in part 1 evidencing local explanatory displays based on Katō’s historical interpretations; Owen Miller and Griseldis Kirsch for their continuous support, and supervision of my doctoral thesis in progress which led me to many sources crucial to the creation of this article.

Notes

Cabinet Secretariat, Kadō shisan wo fukumu sangyō isan ni kansuru yūshikisha kaigi iin meibo [Expert Committee on the Industrial Heritage including Operational Properties member list], 2012; Cabinet Secretariat, Dai-ikkai kadō shisan wo fukumu sangyō isan ni kansuru yūshikisha kaigi [The third meeting of the Expert Committee on the Industrial Heritage including Operational Properties], 2 September 2013.

Stuart B. Smith, “World Heritage Sites of Japan’s Meiji industrial revolution,” TICCIH Bulletin Number 62, 4th quarter 2013, pp. 9-10.

Sankei News, “‘Mono-dzukuri kokka tsukutta Nihonjin no doryoku tsutaetai’ Sangyō isan kokumin kaigi semmu riji Katō Kōko-san” [“‘I want to convey the efforts of the Japanese people who made the country an industrial nation’ Katō Kōko, Managing Director of the National Congress of Industrial Heritage”], Sankei News, 3 July 2015.

Interview with Shimomura Mitsuko by Katō Kōko and Takashima Takeo for Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution website. 10 July 2018; WHCSJMIR, “The way to World Heritage.”

Interview with Shimomura Mitsuko; Daily Shincho and Yahoo News Japan, Talk between Katō Kōko and Satō Masaru .

Daily Shincho, “Paku Kune daitōryō ni ‘90 pāsento no manzoku’ wo ataeta ‘sekai isan’ nippon no shittai” [“Japan’s World Heritage mismanagement which gave President Park Geun-hye approval rate of 90 percent”], 16 July 2015.

At this time, Katō Kōko’s brother-in-law Katō Katsunobu was serving as Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary. See for example Nihon Keizai Shimbun, “Naikaku kanbō san’yo ni Katō-shi ninmei sangyō isan tōroku ni muke [Katō appointed as Special Advisor to the Cabinet – Towards Industrial heritage inscription”, 2 July 2015.

No official job description available, but Katō’s responsibilities as Special Advisor are described for example in Junior Chamber International – Sasebo/ Sasebo shōnen kaigisho, “Kyōshi purofīru [Lecturer profiles]”, in Nextage Sasebo promotional poster, pp.2.

Kobayashi Hisatomo of the Network for Research on Forced Labor Mobilization has investigated Katō Kōko’s privatization of Japan’s industrial heritage production. Details in reference documents from the Network for Research on Forced Labor Mobilization Online Symposium 18 September 2021. Pp. 43-56.

Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution, Interpretation Strategy appendix g)-1, 2017, pp. 83/451.

Kobayashi, “reference documents 18 Sep. 2021,” pp.48-49. New address of the NCIH, shared with three of the Katō family’s companies (the Vacance Corporation, Mutsukado K.K., and Wakō sangyō K.K.) is Japan Fuji Corp. Room 201, 5-28-1 Nakano-ku, Nakano, Tokyo. The address of the Vacance Corporation has not been updated on its official website since the move (as of October 2021), still displaying its old address also previously shared with the NCIH: International Place 5F, 11-16 Yotsuya Sanei-chō, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo.

H.M. Kang, “Abe Administration Signs Massive Contract with Agency Accused of Distorting History,” the Korea Bizwire, 24 June 2020.

NCIH Certificate of full registry records (heisa tōhon) 15 December 2020, shared with author by Kobayashi Hisatomo of the Network for Research on Forced Labor Mobilization.

Cabinet Secretariat, Heisei 28-nendo chihō zeisei kaisei (zei futan keigen sochitō) yōbō jikō [Requests for 2016 local tax reforms (reduction measures for tax burdens)], 2016.

The Yahata Steel outdoor museum was already in place and could easily be visited in 2015, the date of inscription. Nippon Steel supported this local museum and funded it previously, and it was distant from the actual steel production plants. The inscription simply allowed an existing museum to gain World Heritage status. Imai most likely feared more publicity for litigations against Nippon Steel by former forced laborers then underway in Seoul, rather than any potential problems with steel production. See Imai Takashi, “Imai Takashi meiyo kaichō go-aisatsu” [“Greetings from Honorary Chairman Imai Takashi”]. National Congress of Industrial Heritage website. 11 June 2013.

President (magazine), “Ningen kaikō – Imai Takashi x Katō Kōko -‘Hamaguri no kai’ no go-en” [“Human encounter – Imai Takashi x Katō Kōko – destined meeting of ‘Hamaguri no kai’”], 2 February 2015, as cited in “Katō Kōko”, Wikipedia, accessed 4 October 2021.

The NCIH has registered neither Chairman Kojima nor Honorary Chairman Imai in official registration forms which copies are obtainable from Japanese authorities. Confirmed through e-mail correspondence with Kobayashi Hisatomo, 25-29 September 2021.

World Heritage Council for the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution, “Meiji Nippon no sangyō kakumei isan” sekai isan rūto suishin kyōgikai sōkai ga kaisai saremashita” [“‘Meiji Japan’s Industrial Revolutionary Heritage’ World Heritage Route Promotion Council General Assembly was held”], 9 November 2017.

Ōta Narumi, “Gunkanjima moto tōmin ‘chōyōkō sabetsu, kīta koto nai’- Shisetsu de shōkai” [“‘Never heard of discrimination against conscripted workers’ – statement by former Battleship Island resident introduced in the center”], Asahi Shimbun Digital, 14 June 2020.

NCIH Twitter post, “Gaido-san ga Katō Kōko kara kenshū wo ukeraremashita” [“The guides were trained by Kōko Katō”], 9 October 2020.

DHC TV program, “Shinsō fukairi! Toranomon nyūsu” [“Enter deep truth! Toranomon news”], episode aired 1 July 2020. Previously available on YouTube. See also Yano Hideki, “‘Sangyō isan jōhō sentā’ wo kengaku shite” [“Visiting the Industrial Heritage Information Centre”], Kyōsei dōin mondai kaiketsu to kako seisan no tame no kyōdō kōdō website, 4 April 2020.

As of June 2021. See Clément, Herrmann & Phillips, “Report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission,” pp. 56; Yano, “the Industrial Heritage Information Centre.”

See for example Palmer, “Japan’s World Heritage Miike Coal Mine” for more on how official narratives ignores the experience of workers and focus on the acquisition of new industrial machines to glorify the Meiji Era industrialization. Palmer’s investigation of allied POW’s as wartime forced laborers in the Miike Coal Mine is also highly relevant to this discussion.

Ryoko Nakano, “Mobilizing Meiji Nostalgia and Intentional Forgetting in Japan’s World Heritage Promotion,” International Journal of Asian Studies 18 (1), 16 September 2020, pp. 27.

Sakurai Yoshiko, “Japan’s new Prime Minister expected to follow Abe’s historical perspective,” translated from “Renaissance Japan” column no. 918 in the 24 September 2020 issue of The Weekly Shincho.

NCIH Twitter post, “APA gurūpu daihyō no Motoya Toshio-sama ni sentā ni okoshi itadakimashita!” [“APA Group representative Motoya Toshio came to our centre!”], 6 October 2020.

NCIH Twitter post, “Yamaoka Tetsuhide-sensei go-ikkō sama ni sangyō isan jōhō sentā wo saihō itadakimashita” [“Yamaoka Tetsuhide and affiliates visited the Industrial Heritage Information Centre again”], 13 November 2020; NCIH Twitter post, “Yamaoka Tetsuhide-sensei ni go-raikan itadakimashita!” [“Yamaoka Tetsuhide visited our centre!”], 20 October 2020.

NCIH Twitter post, “Hachigatsu mikka ni Kento Girubāto-sama ni okoshi itadakimashita!” [“Kent Gilbert visited on 3 August!”], 7 October 2020.

NCIH Twitter post, “Honjitsu wa Shijitsu wo sekai ni hasshin suru kai no mina-sama ga go-raikan saremashita!” [“Today, the members of the Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact visited our centre”], 25 January 2021.

Both Sakurai Yoshiko and Kent Gilbert features extensively, denying the history of Japanese military sexual slavery in Miki Dezaki’s highly relevant documentary movie Shusenjo: The Main Battleground Of Comfort Women Issue, 2018. See trailer on YouTube.

Motoya Toshio is the head of APA Hotels, one of Japan’s largest hotel chains. Motoya authors neo-nationalistic books under the pen-name Seiji Fuji in which he denies the Nanking Massacre and Japanese wartime sexual slavery. For example, Theoretical Modern History II – The real History of Japan – Japan Pride IV – A proposal for revival (2016). His books, some in both Japanese and English, are sold in APA hotel receptions and placed in every guestroom in every APA hotel. See for example BBC News Japan, 19 January 2017.

Shoheijuku website, “Sangyō isan kokumin kaigi senmu riji Katō Kōko-sama [Kōko Katō, Managing Director, National Congress of Industrial Heritage],” Dai 113-kai Shoheijuku getsureikai repōto, 25 November 2020.

Bunkajin TV, “‘Gunkanjima, shin no rekishi,’ Sangyō isan jōhō sentāchō Katō Kōko-shi x Katō Kiyotaka no SP taidan kanzenban” [“‘Battleship Island, the real history,’ Industrial Heritage Information Centre Director Katō Kōko and Katō Kiyotaka’s talk special – full edition”], YouTube video, 2020 (accessed 14 March 2021, but has since been made private).

Kent Channel, “Kento Girubāto osusume! ‘Sangyō isan jōhō sentā’ ni tsuite Gunkanjima moto tōmin no shōgen” [“Kent Gilbert recommends! About the ‘Industrial Heritage Information Centre’ – Testimonies of former residents of Battleship Island”], YouTube video, 20 August 2020.

DHC TV program, “Shinsō fukairi! Toranomon nyūsu [Enter deep truth! Toranomon news],” aired 17 November 2020, previously viewable on YouTube (accessed 24 March 2021); DHC TV program, “Shinsō fukairi! Toranomon nyūsu [Enter deep truth! Toranomon news],” aired 1 September 2020. Viewable on YouTube (accessed 4 October 2021).

“Nyūsu Joshi” was produced by DHC TV and was until March 2018 broadcasted on Japanese TV station Tokyo MX. Tokyo MX stopped broadcasting the show after they faced lawsuits and were warned by the Broadcasting Ethics & Program Improvement Organization of Japan over hate-speech related human rights infringements in an episode broadcasted in 2017. It discussed protests against US military bases on Okinawa. “Nyūsu Joshi” referred to protestors as “terrorists” and suggested protests were actually led by a small Zainichi Korean organization against hate speech whose leader was named on the show. DHC TV continued to broadcast the now highly controversial “Nyūsu Joshi” on their own platforms, resulting in a new lawsuit against them. DHC TV decided in January 2021 to stop production of the show and published the last episode in March 2021. Katō Kōko appeared on the show in February 2021 amidst the ongoing anti-Korean hate speech controversy. A Tokyo court ruled in September 2021 that DHC TV must pay compensation and publicly apologize for defamation of the Zainichi organization leader. CEO of DHC TV is refusing to apologize, and the broadcaster continues to be criticized for disseminating hate speech against Koreans. See Mizuno Yasushi, “The stain left on broadcasting history by ‘Nyūsu Joshi’” [“‘Nyūsu joshi’ ga hōsō-shi ni nokoreta oten”], President Online, 30 September 2021.

DHC TV program, “‘Nyūsu joshi’ #305 (Meiji Nippon no sangyō kakumei isan kara manabubeki koto. Hinshi no masumedia ni kiku tokkōyaku)” [“‘News women’ nr. 305 (What can be learned from Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. Special medicine effective for the weak mass media)”], 16 February 2021.

An Chaesŏng, Shinbulsan: Ppalch’isan Ku Yŏnch’ŏl saengaesa [Shinbulsan: The life story of freedom fighter Ku Yŏnch’ŏl] (Sanjini 2011).

Chang Chaewan, “‘Nuumyŏn kŭnyang songjang… Saramin’ga shiptŏranikke’” [“‘Just a corpse if lying down… Not like living humans’”]. Oh My News, 31 January 2011.

Channel A News 2017, “‘Nanŭn kunhamdo 4416pŏniŏtta’ saengsaeng chŭngŏn” [“‘I was no. 4416 on Battleship Island’- vivid testimony”], 16 July 2017.

Yi Hyosŏk, “‘Kunhamdoesŏ sogoshipko chumŏkpap mŏkŭmyŏ noyŏk…Choguk wŏnmanghaetta’” [“On Battleship Island I wore underwear and ate rice balls while working… I resented the homeland’”]. Yonhap News, 27 July 2017.

Yun Yongmin, “Kŭllojŏngsindae simin moim, 3~7il il kangjejingyong chiyŏk tapsa” [“Women’s labor force citizen meeting, forced conscription survey in Japan from 3rd to 7th”], News 1, 1 June 2015.

NCIH and Hashima Islanders for Historical Truth, Video Message “Who is Yeon Cheol Koo?,” 18 May 2019.

“detarame na otoko” – translated as Ku Yŏnch’ŏl himself being “rubbish” in the video’s official English subtitles. Directly translatable as “nonsensical man.”

Katō Kōko, “Tondemo Kankokujin ni Gunkanjima no moto jūmin ga gekido, Nippon e no zōo wo aoru kōtōmukeina gendō to wa” [“Former residents of Battleship Island are raging against crazy Korean – These are his preposterous actions that stirs hate against Japan”]. Daily Shincho, 25 February 2019.

Katō Kōko, UNESCO Decision and UNESCO-ICOMOS Expert Report, statement on website Truth of Gunkanjima, 4 August 2021.

NCIH and Hashima Islanders for Historical Truth, The Residents of Hashima Island voice how much they are angry towards the 44th UNESCO Decision, video posted 19 August 2021.

Nakamura’s role as Chief Guide of the IHIC can be confirmed in Clément, Herrmann & Phillips, “Report on the UNESCO/ICOMOS mission,” pp. 52.

The contents of the article have been posted online with English translations by Japanese blogger Nishitatsu1234 on his blog, 16 August 2021.