Abstract: The International Olympic Committee and local Olympic organizers promised that the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics would change the South American city. Almost all the promises were broken despite Brazil spending at least $13 billion to organize the games, with some estimates suggesting $20 billion. The Olympics turned into lucrative real estate deals for several billionaire developers. It did manage to drive the construction of a $3 billion metro-line extension, but estimates say it cost 25% more than it should have. Mostly the Rio games were scarred by scandals and left a city, starkly divided by rich and poor, pretty much as it was with a few cosmetic changes.

International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach lowered the curtain on the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro with these words, spoken at the closing ceremony before a sellout at the 78,000-seat Maracana Stadium.

“These Olympic games are leaving a unique legacy for generations to come. History will talk about a Rio de Janeiro before and a much better Rio de Janeiro after the Olympic Games.”

He stood on a stage with local organizing committee president Carlos Nuzman, who also headed the Brazilian Olympic Committee. Nuzman was a powerful IOC member who landed the games for Rio, and Bach called him a “dear colleague and friend” during the speech as he made another pledge. Nuzman had often repeated the same pitch, comparing Rio to the rebirth that Barcelona is credited with getting from the 1992 Olympics. Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes, who hoped to ride the Olympics to a state governorship and even the national presidency echoed the same theme and was the IOC’s main go-to-guy. As an aside, Paes was badly defeated in 2018 in a run for Rio state governor, soiled by the Olympic fallout.

“We will continue to stay at your side after these Olympic Games,” Bach said. “We arrived in Brazil as guests. Today we depart as your friends. You will have a place in our hearts forever.”

That was Aug. 21, 2016. The next morning at a “thank-you breakfast,” Bach awarded the “Olympic Order in Gold” to both Nuzman and Paes. “My heart is full of gratefulness, my heart is full of thanks,” Bach said, draping them with gold-leaf necklaces adorned with the five Olympic rings.

As far as it’s known, Bach has not returned to Rio de Janeiro since then, and there are good reasons. Rio is not a legacy the IOC talks much about, nor one Bach wants to revisit. Two years before the Rio Olympics opened, IOC vice president John Coates, who had already been on a half-dozen visits to Brazil with a team of IOC inspectors, said the preparations for Rio were “the worst I have ever experienced.” Things of course improved and the Olympics took place. Except during wartime, they always have. Nowadays, that’s because television pays billions for broadcast rights and demands it. There is no doubt the IOC was relieved to get out of town alive before the Paralympic opened three weeks later. Bach did not return for the closing ceremony of the Paralympics, either.

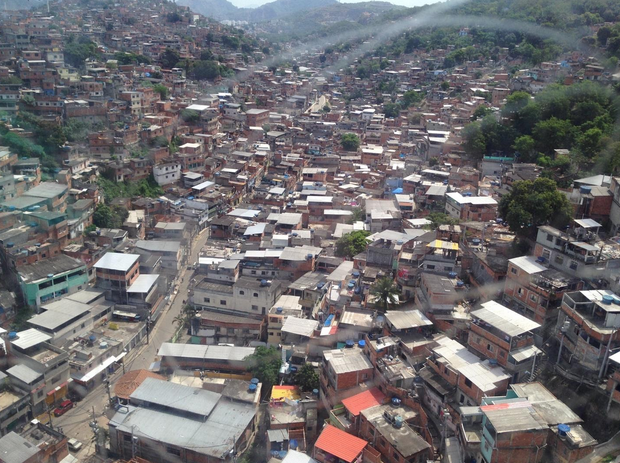

The Rio Olympics were scarred by scandals, land deals to build Olympic projects that displaced thousands of the poor, dangerous levels of viral and bacterial pollution in waterways used for Olympic events, the Zika virus, and many myths – that’s the mild word – about what the Olympics would do for Latin America’s most populous country. As a closing act, the local organizing committee needed a multi-million dollar government bailout in order to run the Paralympics. Save for minor cosmetic changes that included a $3 billion metro line extension that state auditors said cost 25% more than it should have, a city fractured by mountains and searing inequality remained much the same. Many blame graft among politicians and construction companies for the overbilling, which also was reported on several Olympic-related projects. Predictably, construction costs soared as the Olympics approached and deadlines had to be met.

The Olympics took place largely in the south and west of the city, which is largely white and well-off. The rest of Rio is a hodgepodge of dilapidated factories, hillside slums, and some prosperous pockets with the threat of violent crime around any corner. Crime was mostly hidden away during the Olympics but spiked afterward, driven by a grinding recession and stepped-up security that vanished after the games ended.

Exactly one year after the Olympics closed, I interviewed Igor Silverio alongside the new port built for the Olympics, anchored by the gleaming-white “Museum of Tomorrow” by futurist Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. The renovation that was centered on Plaza Maua may have been the best legacy of the games. Igor was there kicking a soccer ball around with his two children. He lived in a nearby favela and said the port area was vastly improved over the same area that in his youth was known for decay and drunkenness.

“For sure it’s better,” he said. But he added he “expected more from the Olympics.”

“From my point of view, the Olympics only benefited the foreigners. Local people themselves didn’t get much. The security situation isn’t good, the hospitals. I think these are investments that didn’t benefit many local people.” He said he skipped attending Olympic events because they were “too expensive” and located far away in the suburbs.

Standing outside a new subway line a year after the Olympics closed, domestic worked Isa Trajano Fernandes said public transportation had improved but was still poor. “When the Olympics were going on it was better, but they let it slide,” she said.

Embarassment and Missed Opportunity

The Rio Olympics were a missed opportunity for Brazil and an embarrassment for the IOC, although they were met with euphoria on Copacabana Beach with 50,000 people cheering when they were awarded in 2009 in Copenhagen. President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was among those celebrating in Denmark, crying as he hugged soccer legend Pele.

“Now we are going to show the world we can be a great country,” Lula said.

Brazil is a fascinating and friendly country, but it did not acquit itself well as it prepared for the Olympics, drawing unwanted attention to its defects rather than the kind of “fawning, soft coverage” it might have expected from an event like the Olympics. I mean, who could be against the Olympics? That’s what local organizers and politicians must have thought as they sought the games.

Less than two months after the games ended, Nuzman was arrested and jailed briefly in a vote-buying scheme. More than three years later his trial in Brazil remains in the hearing phase, creeping through the country’s tainted judicial system. Brazilian and French authorities allege that Nuzman helped direct about $2 million in bribes to African IOC members in order to land votes for Rio in the election in Denmark. The Tokyo Olympics have been embroiled in a similar scandal that forced the resignation in 2019 of Japanese Olympic Committee President Takeda Tsunekazu.

Takeda Tsunekazu, Abe Shinzo and Inose Naoki seal deal for 2020 Olympics

Former Rio de Janeiro state governor Sergio Cabral _ another fervent Olympic booster _ has been jailed and convicted on 12 counts of corruption. He told a Brazilian federal judge that Nuzman, in fact, directed $4 million in bribes. Nuzman has denied any wrongdoing. Court filings say Nuzman had undeclared assets in Switzerland, including 16 gold bars weighting one kilogram each. Prosecutors estimated his net worth had increased 457% in his last 10 years as the head of the Brazilian Olympic Committee.

At the time of his arrest late in 2016, Nuzman’s organizing committee was reported to still owe creditors between $30-40 million, and many of the projects built for the Olympics were linked to a corruption scandal that blanketed the country. Prosecutor Fabiana Schenider said the “Olympic Games were used as a big trampoline for acts of corruption.”

“While Olympic medalists chased their dreams of gold medals, leaders of the Brazilian Olympic Committee stashed their gold in Switzerland,” she added.

Brazil says it spent about $13 billion to organize the Olympics in a mix of public and private money, though some estimates suggest it was $20 billion. Amazingly, these were billed as low-cost Olympics after Beijing spent more than $40 billion in 2008 and Sochi poured out $51 billion for the 2014 Winter Olympics.

Rio’s Olympics left behind a half-dozen empty sports venues without tenants and with taxpayers footing the bill. Rio’s Olympic Park, the center of the action four years ago, was recently closed for safety concerns. A judge ordered it reopened 13 days later. The park is a largely treeless expanse of concrete with little shade and few amenities. It has staged music concerts, e-sports events, and a patchwork of other events. Public schools are also using the park, with mostly failed efforts to get the private sector involved.

Something Rotten in Denmark?

Scandal surfaced almost the minute that Rio was awarded the Olympics in Copenhagen. Chicago was perhaps the favorite, and had the strongest technical bid, but was eliminated in the first round despite the presence of President Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey. The result was a shock and should have immediately raised red flags. Madrid and Tokyo were the other candidates. Reports blamed anti-American sentiment for Chicago’s early exit, and the difficult relationship that existed at the time between the U.S. Olympic Committee and the IOC.

Rio kicked up scandals large and small. Many involved real estate deals and construction contracts. One centered on the construction of an Olympic golf course _ a project driven Rio Mayor Eduardo Paes _ that was carved out of a protected nature reserve in a country where almost no one plays golf. In fact, Rio already had two courses, and one could have been renovated for the Olympics. The project was slowed by environmental lawsuits and the start-and-stop financing of a Brazilian billionaire, who was also a political supporter of the mayor. In a deal with the city, billionaire developer Pasquale Mauro spent a reported $20 million to build the course in exchange for permission to build more than 100 multi-million-dollar apartments on some of Rio’s most desirable real estate. The mayor managed to slip through legislation just before Christmas in 2012, setting in motion the construction.

Olympic Golf course under construction

The course was designed by American golf architect Gil Hanse, a layout with undulating fairways that bumped up against scrubland brimming with wildflowers and nesting owls. The course design won wide praise, though Hanse told me early in the project that he was frustrated with delays and wasn’t getting paid on time by the Mauro family. The course was billed as the first public championship-level course in the country. Known as “Riserva Golf,” condos featured luxury apartment towers resplendent in glass, marble and chrome in the Rio suburb of Barra da Tijuca. Initial prices were listed at between $2.5-7 million. A small group of determined protesters, calling themselves “Golfe Para Quem” (Golf For Whom), were often posted on Avenida America just outside the venue. Some likened building a golf course in Rio to building a bullring in Finland.

Paes brushed if off.

“I think during the Olympic games there’s always going to be a lot of controversy,” Paes said at the course opening in 2015, standing next to Mauro as he called the course “a great environmental legacy.”

Carlos Carvalho, another real estate magnate and a political supporter of the mayor, got the go-ahead to develop the Olympic Village, a complex of 3,600 apartments that was to be sold off after the games. Alberto Murray Neto, a lawyer and a former member of the Brazilian Olympic Committee, told me several times by phone from Sao Paulo that the Rio Olympics “were nothing more than a real estate deal.” Murray was a long-time, outspoken critic of Nuzman, and Murray’s grandfather _ Sylvio de Magalhaes Padilha _ was a former IOC vice president and an IOC member from Brazil for almost 40 years.

An ugly scandal played out when IOC member Patrick Hickey of Ireland was arrested in Brazil on charges of scalping valuable tickets during the Olympics. Hickey was taken into custody at his hotel room around dawn and held in a Rio jail for several weeks. In a video he’s seen being taken away in his bathrobe in the raid on his five-star hotel. He answered the door nearly naked, but that was edited out of a video that went viral. Hickey denied the charges and the case has yet to come to trial in Brazil. Hickey has self-suspended himself as an IOC member, but the IOC Ethics Commission has still not ruled on the case. The Olympic umbrella body ANOC _ Association of National Olympic Committees _ put up about $400,000 in bail money to get Hickey out of Brazil. It has since written off the loan. There were also reports that prosecutors wanted to question Bach about email exchanges he had with Hickey related to Ireland’s ticket allocation. Bach was not implicated in any wrongdoing, but newspapers in Brazil have speculated this also may have given him another reason not to return to Rio and take a chance of facing investigators.

It’s worth noting that the roughly 100 IOC members like Hickey receive per diems of between $450-900 when they are on “Olympic business.” They also get first-class flights, rooms in top hotels, and are treated like diplomats or prime ministers as they move around town during the games, often in chauffeured cars. Bach receives no salary and is listed technically as a “volunteer.” He does receive a yearly “indemnity” of about $250,000 and has his Swiss taxes paid for him _ $121,000 listed in 2018 IOC report _ as well as accommodations in a luxury Swiss hotel. By contrast, organizers used 70,000 unpaid volunteers in Rio, and will use about 80,000 in Tokyo. By not paying this work force, even a minimum wage of $10 per hour, the IOC saves an estimated $100 million, maybe more. Olympic officials acknowledge they would not run the Olympics without the volunteers. Joel Maxcy, the president of the International Association of Sports Economists who teaches at Drexel University, told me “it’s very clearly economic exploitation.” Maxcy described a situation in which volunteers assembled the product but “someone else is collecting nearly all of the money derived from those labor efforts.”

Grading the Sporting Part: Maybe a C+

The sporting part of the Rio Olympics was graded as a relative success. Brazil’s men’s soccer team won the gold medal, the only major championship it lacked, and star Neymar cried as he kissed the ball. American gymnast Simone Biles won four gold medals, and Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt won three more golds. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a cameo appearance at the closing ceremony, showing up as computer game character Super Mario. The sports and the color are always a hit and temporarily distract from the cost of putting on the show, and who is making all the money; not many of the athletes. I recall giving the games a C+ grade in an interview on Canadian television. That seemed about right. It might have been higher, but there were often too many empty seats at the venues. And there were other “glitches,” as organizers often called the problems. During the games, a bullet fired from a nearby slum _ called a favela in Brazil _ ripped through a tent at the equestrian venue. Nobody was injured. The swimming pools used for water polo and diving turned bottle-green when organizers apparently mixed chlorine with hydrogen peroxide. And a camera suspended by cables in the Olympic Park, where thousands were strolling around, fell and injured two.

Despite the problems, most residents of Rio were proud when the games finally happened, defying all odds. There was a general sense of relief that the country had pulled off South America’s first Olympics.

“I think the Olympics and Paralympics were a boost to the self-esteem of Brazil,” Mauricio Santoro, an international relations expert told me. “They happened when everything was going so bad in Brazil. The mere fact they happened without serious problems, without an infrastructure disaster, without a terrorist attack, made Brazil feel better about itself.”

The bar for success was very low.

Both the Olympics and 2014 World Cup were awarded at a time when Brazil was portrayed as a rising power. But the country slipped into a deep recession as the shows were being readied. The Olympics and World Cup can’t be blamed for all of Brazil’s problems, but they did expose the danger of hosting these large events in a country that lacks so many of the basics. And the IOC can be faulted for looking the other way and, in fact, encouraging Brazilian politicians to splurge on white elephant sports venues. And of course, the corruption defiles the IOC, which talks about promoting virtues like fairness, equality, and self-sacrifice. The same was true for FIFA, the world governing of body of soccer. Brazil used 12 new or renovated stadiums for the 2014 World Cup _ FIFA required only eight _ which guaranteed white elephants. Politicians from all over the country wanted a stadium, and the corrupt leadership of the Brazilian Football Confederation was happy to oblige. Three of the most recent presidents _ Ricardo Teixeira, Jose Maria Marin, and Marco Polo Del Nero _ were scoundrels. Teixeira was found guilty of taking bribes and money laundering and resigned for “health reasons.” FIFA banned him from the game for life. Marin was arrested in Switzerland and served time in the United States for wire fraud, money laundering and racketeering. Del Nero was also banned for life from the game by FIFA, accused of bribery and money laundering.

The stadiums were built in some cities that did not even have top teams, or barely any professional teams at all. The city of Cuiaba in the far west of Brazil comes to mind. The capital of the depopulated state of Mato Grosso, Cuiaba was reported at the time to have 29 million head of cattle _ 10 times the human population. There was money for a soccer stadium, but not much for health care. I visited a cinderblock clinic just a short walk from the stadium. It was overflowing with 30 patients sitting inside and outside a sweltering waiting room. “Ordinary people have been forgotten,” Evone Pereira Barbosa, a maid waiting outside, told me. “They invested a lot in the World Cup and forgot the people.”

Despite all the misconduct and impropriety, the World Cup and the Olympics presented an opportunity to write about Brazil’s brutal history of race and slavery, which much of the world knows little about. It was possible to draw readers into what looked like a sports story, and then talk about something else. For instance, Brazil imported about 5 million African slaves, which is 10 times more than the United States. And it abolished slavery in 1888, 25 years after the United States. Slavery is critical to understanding modern Brazil, which is often portrayed incorrectly as a racial democracy. It’s difficult to define who is black in Brazil, though one researcher of color told me it’s “easily understood if you try walking into a top-class restaurant.” Many Brazilians self-identify. Two people of similar skin tones may identify differently. One as black. One as white. In a famous case, two identical twins applied for university admission under an affirmative-action program. Only one was judged by admission officials to be black. In a famous survey done in 1976, people were asked to describe their skin colors and came up with 136 variations _ from brown to cinnamon to wheat and 133 other shades.

Lots of Attention; Much Unwanted

Brazil President Dilma Rousseff was removed from office in an impeachment trial just days after the Olympics closed. A billion-dollar corruption scandal was buffeting the state-directed oil company Petrobras at the time. The corruption probe into Petrobras _ known as Lava Jato in Portuguese, or Car Wash in English _ caught many of the country’s largest companies paying bribes to politicians to get contracts from Petrobras. The construction giant Odebrecht, which had its hands in many of the Olympic projects, was among those getting contracts.

President Dilma Rousseff (in green shirt) before her ouster

Only a handful of world leaders attended the Rio Olympics, compared to about 100 in 2012 in London. And Brazil’s reputation, instead of getting a boost, probably suffered as the Olympics focused unwanted attention on underfunded schools, endemic racism, and understaffed hospitals, and raised questions about the priorities of politicians and the IOC. It also made clear the way politicians can use the Olympics to rally support, allowing them to overlook real priorities and hide behind flag waving and the “fun and games” of the Olympics. In the case of Rio, it meant overlooking basics like providing public sanitation to everyone in a city of 7 million, which is deeply divided by the wealthy in the south and west, and the rest living in hillside shanties or sprawling encampments near garbage dumps.

It seems impossible that a city chosen for a sporting jewel like the Olympics would lack basic sanitation for millions. Rio dumps more than 50% of its untreated waste _ some estimates were as high as 70% _ into the city’s famous Guanabara Bay, which is framed by the Christ the Redeemer statue and Sugar Loaf Mountain.

Glorious Rio viewed from above

The Olympics and the World Cup were supposed to focus attention on the problem and help solve it. In Rio’s Olympic bid, it promised to improve the situation. It didn’t. “It was a wasted opportunity,” Mayor Paes, in a few moments of candor, acknowledged more than once. It was a problem the IOC overlooked, and often defended. A year before the Olympics opened, Nawal El Moutawakel, a gold-medal Moroccan hurdler in 1984 who headed the IOC inspection team for Rio, was asked if she would swim in the bay.

“We will dive in together,” El Moutawakel said, grinning and pointing to other IOC officials she said would take the plunge with her.

Olympic sailing was eventually held in the bay with sailors forced to dodge floating debris that could include dead animal carcasses. As a stopgap, government helicopters using GPS flew overhead on competition days to spot massive flows of detritus carried by the tide. Trash boats below were dispatched to rake in the rubbish, and sailors also got notice about what was out there and how to avoid it. Organizers also built dams to catch garbage as it flowed down from hillside favelas headed for the bay. Of course, the barriers could not catch human waste, and several reports said hospital waste was being dumped into the water.

Sailors talked openly about seeing dead animals floating in the water, maneuvers to dodge water-logged sofas, and joked with black humor about “the science” of untangling plastic bags from rudders and center boards.

“I think no sailor feels comfortable sailing here,” Ivan Bulaja, a former Olympian and an Austrian sailing coach, told me. “I guess you could get seriously ill.”

The open sewer also produced great quotes for reporters looking for descriptive material.

“At low tide it smells like sewage water. It smells like a toilet,” Austrian sailor Nikolas Resch told me. He was fourth in the London Olympics in the 49er class with teammate Nico Della Karth. “You see people going for a swim. I would never, under free will, go into the water here.”

Allan Norregaard won a bronze medal in 2012 for Denmark. He described sailors jumping into the water and coming out with red dots on their bodies.

“I have sailed around the world for 20 years and this is the most polluted place I have ever seen,” he said. “I don’t know what’s in the water, but it’s definitely not healthy.” Other sailors routinely termed it an “open sewer” and Mario Moscatelli, a Brazilian biologist and environmentalist, used more formal language.”

“It’s a latrine,” he said.

Just days before the Olympics opened, Rio’s waterways were as filthy as ever, contaminated with raw sewage teeming with dangerous viruses and bacteria. It was all well documented in a 16-month study by the Associated Press. An open sewer ran by the main press center for the Olympics, and the stench was unmistakable. The same was true for the Athletes Village, which also had an open sewer located just a one-minute walk from an entrance to the village. And all visitors to Rio de Janeiro know the smell of raw sewage that’s constant on a taxi ride from Rio’s international airport Galeao to the center of the city, or to the Copacabana and Ipanema areas in the south.

The first results of the AP study published a year before the Olympics showed viral levels in some Rio waterway at levels up to 1.7 million times “what would be worrisome” in the United States or Europe. It was difficult to document how many athletes got ill, and only a few cases were reported. Teams shied away from talking about it, and athletes tried not to be distracted. It’s clear that rowers, sailors, distance swimmers, and triathletes took precautions, preventatively taking antibiotics, bleaching rowing oars, and wearing plastic suits and gloves in a bid to limit contact with the water.

A biomedical expert quoted by AP had this advice for travelers to Rio. “Don’t put your head under water.”

Rio is a spectacular-looking city in some parts, and it showed up well on television for the Olympic audience. Which is one reason it was chosen. From a distance, Guanabara Bay is majestic as it flows into the Atlantic alongside Sugar Loaf Mountain. Networks like NBC in the United States, which pays about $1 billion for the broadcast rights to each Olympics, loved the backdrops that included Copacabana and Ipanema beaches. By the way, areas of Copacabana and Ipanema also have serious water pollution problems, and Copa is where many TV networks set up studios for their broadcasts. Through the miracle of television, every Olympics look pretty much the same from inside a venue _ say a basketball arena, or a soccer stadium, or the venue for swimming. They are like studio sets and could be located almost anywhere.

“The Olympics have become more sponsor-and television-driven,” David Wallechinsky, president of the International Society of Olympic Historians, told me. “In Rio, it was a mess. Yet on television it looked fine. Let’s face it, 99% of the people who follow the Olympics do so on TV. So whatever you present them on TV is reality, though those of us on the ground see a different reality.”

Wallechinsky, who is one of the foremost authorities on the Olympics, called the failure to clean Guanabara Bay a scandal. He said Rio’s godsend was its friendly people and the fact that sensational sporting performances and nationalism usually overshadow other problems, at least during the 17 days of the games and for a few weeks after.

“I don’t think the International Olympic Committee is going to go to a developing city any longer,” he said. “They don’t want that anymore. They want cites that are ready.”

That’s why Tokyo was chosen, billing itself in Buenos Aires as “A Safe Pair of Hands” when it was picked in 2013.

Paralympics Almost Don’t Happen

The Paralympics with over 4,000 athletes opened three weeks after the Olympics closed. It took its own beating. Organizers began slashing budgets everywhere in the months before the Olympics. In fact, they literally ran out of money to run the Paralympic Games. Sidney Levy, the CEO of the organizing committee, told Paralympic organizers just a few weeks before that there was no money left to run the Paralympics. It shocked everybody.

“This is the worst situation that we’ve even found ourselves in at the Paralympic movement,” Philip Carven, the president of the International Paralympic Committee, told me. “We were aware of difficulties, but we weren’t aware it was a critical as this.”

At the time the Rio city government promised about $46 million in a bailout and the national government said it would guarantee another $30 million.

Bach got caught up in the mess and, at the press conference the day before the Olympics closed, flatly denied there was any public money being used to patch up the local, privately funded operating budget. This was not accurate, but fooled many reporters from out of town who didn’t take time to check the facts.

“There is no public money in the organization of these Olympic Games,” Bach said the day before the Olympics closed. “The budget of the organizing committee is privately financed. There is no public funding for this.”

A federal agency for Olympic legacy in 2017 put the cost of the Rio Olympics at about $13.2 billion. Most of that was public money except for a $2.8 billion privately funded operating budget. And it needed public money at the end, too.

A Brazilian named Mario Andrada had the job for several years of handling the media, trying to explain Rio’s problems. He was always available and kept a sense of humor most of the time. He gave me a lead once on the fact that 450,000 condoms would be distributed at the Olympics. That story, of course, got good play _ and not just in the tabloids. That’s 40-45 condoms per athlete over 17 days. The condom distribution machines at the Olympic Village read: “Celebrate with a Condom” in English and several other languages.

Mario also came up with the best quote during the Olympics. He tried to explain the green water in the diving and water polo pool, talking about the chemical imbalance in the water. A native speaker of Portuguese with strong English, he still got his words twisted.

“Chemistry isn’t an exact science,” he said, speaking to hundreds of reporters from around the world. In fact, it is an exact science. What he meant to say was: “Chemistry is an exact science, and we got it wrong.”

Andrada usually talked freely, which I appreciated. But he also acknowledged another reality.

“I usually say too much because I can’t always get the right word in English. The press loves me.”

We did, and we loved his quotes.

—-

I reported from Rio de Janeiro for 4 and half years for the news agency Associated Press. What’s compiled here is almost entirely from my own reporting with help from AP colleagues; a compilation of hundreds of stories assembled as Brazil was organizing the World Cup and Olympics. Associated Press gave me the privilege of reporting from Brazil, which became a full-immersion course in the country. I am grateful for being able to use sports as a window into wider themes. Brazilians were almost always gracious, forgiving of my atrocious Portuguese, and open to explaining their continent-size country.