Abstract: In 1936, after the Berlin Olympics concluded, Tokyo won the right to host the 1940 Olympics. The sequence of events that led to the 1940 games’ forfeiture can be said to have begun on July 7, 1937, when Japanese and Chinese troops clashed at the Marco Polo Bridge southwest of Beijing. The IOC’s initial reaction was to transfer the 1940 games to Helsinki; but with Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, the ‘missing Olympics’ were cancelled for good.

Saturday, September 21, 1940 — the day the Twelfth Olympiad was scheduled to have begun — the weather in Tokyo was sunny with a brisk breeze, and a high temperature of 23.2 degrees Celsius. History records that on that day, the British government officially approved use of the London Underground as an air-raid shelter. The following day, September 22, the RAF bombed Berlin and columns of the Japanese 5th Infantry Division crossed the border from China’s Guangxi Province into French Indochina.

In July 1936, with Germany’s backing, the International Olympic Committee picked Tokyo over Helsinki to host the 1940 games, by a vote of 36 to 27.

Two years later, due to heavy international criticism of its military incursions in China, Japan unilaterally withdrew from hosting the 1940 games, which, like the 1944 games, were never held. Japanese referred to them today as “Maboroshi no Orinpikku” — “The Olympics that never were.”

The first modern-day Olympic games were held in Athens in 1896. Twelve years later, Japan sent its first contingent to Stockholm, and took its first two gold medals in Amsterdam in 1928.

Tentative moves toward promotion of Tokyo as host began as early as 1929, when Swedish industrialist Sigfrid Edström, an organizer of the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, visited Japan and discussed Tokyo’s prospects with Yamamoto Tadaoki, chairman of the Inter-University Athletic Union of Japan. A year later Yamamoto, who traveled to Germany as head of Japan’s contingent to the International Student Games, was urged by Tokyo’s mayor-to-be Nagata Hidejiro to put out feelers about an Olympiad in Japan’s capital.

Hosting the games, Nagata felt, would serve as a way of feting Tokyo’s recovery from the earthquake and fire that had devastated the city in September 1923. (Hashimoto 2014) If held in 1940, the games would overlap with plans for commemorating the 2,600th anniversary of the ascension of Jimmu, legendary first emperor of the Yamato Dynasty. In addition, plans were also hatched for the city to host a 1940 world exposition. It would be a gala year.

Japan’s representatives to the IOC, educator Kishi Seiichi and Judo founder Kano Jigoro, were respected individuals passionately involved in amateur sports who worked tirelessly to promote Tokyo at the grass-roots level. (Neither lived to 1940, the former passing away in 1933 and the latter in 1938.)

Another influential figure, Count Soejima Michimasa, represented Japan at the general meeting of the International Olympic Committee in May 1934, where he proposed Tokyo’s hosting of the event.

Tokyo initially expected its selection to be a shoo-in, but by 1935 no fewer than nine countries had declared their candidacy, with Rome and Helsinki considered viable contenders. In 1935 Count Soejima, accompanied by diplomat Sugimura Yotaro, personally met with Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini to persuade Il Duce to withdraw Rome as a candidate city. (Uemae 1976)

Although Japan’s incursion into Manchuria from September 1931 had come under heavy international criticism, the IOC’s president, Belgian count Henri de Baillet-Latour was predisposed to treat politics and sports as separate issues, and in July 1936, with Germany’s backing, Tokyo won out over Helsinki to host the next games. (Hashimoto 2014)

At Berlin, Japan finished 8th overall with 6 gold medals, including both men’s and women’s breast-stroke events and the Marathon, 4 silvers and 8 bronze.

At the closing ceremonies of the 11th Olympiad in Berlin — memorialized in Leni Riefenstahl’s film “Olympia” — IOC President Latour announced to the crowd, “It has been decided that the next Olympics, in 1940, will be held in Tokyo.”

Model poses with strings of pearls arrayed in the Olympic logo.

After a brief hesitation for the news to sink in, the members of the Japanese contingent began shouting “Banzai!” with both arms raised. Athletes from other countries who were expecting to compete in Japan besieged members of Japan’s team, asking for their home addresses so they could look them up four years later.

The news was quickly dispatched to Japan and by late the same evening, people carrying paper lanterns marched in celebration to the Nijubashi bridge outside the palace and to the Meiji Shrine.

Activities and Venues

Planners moved forward with a schedule of events. It was decided the 1940 opening ceremony was to be held at 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, September 21, and the closing ceremony at 2:00 p.m. on Sunday, October 6. A total of 20 events were planned, including track and field; shooting; swimming; field hockey; water polo; fencing; gymnastics; weightlifting; basketball, wrestling, cycling, boxing, modern pentathlon, equestrian, yachting and baseball.

In addition to the Meiji Jingu stadium and sports complex in Shibuya, two existing facilities still in use date back to the planning stages of the 1940 Olympics. They are Baji Koen (Equestrian Park) in Setagaya Ward, and the Boating Course on the north bank of the Arakawa River in Toda City, Saitama.

While many mistakenly assume that the Equestrian Park, a part of the Yoga district of Tamagawa Village, was intended from the beginning as a venue for the 1940 games, it was actually established to celebrate the birth on December 23, 1933, of crown prince Akihito, who in 1989 became the Heisei emperor. Prior to then, no civilian equestrian facility had existed in Japan.

Fifty thousand “tsubo” (approx. 3.3 square meters) of mostly wooded land was procured, at the price of 6 yen per tsubo. The park was officially named in 1936, the year an additional 15,000 tsubo were added for dormitories, housing and garages. Much of the manual labor was provided in the form of “kinro hoshi” (labor service) by student “volunteers” from neighboring Tokyo Agricultural University. (Japan Racing Association)

The original Kokugikan sumo auditorium in Ryogoku, completed in 1909 on the same site as the present-day arena, would have been the venue for Greco-Roman wrestling, weightlifting and boxing.

Development of the golf course at Komazawa in Setagaya Ward, which was to be used jointly for Olympic events and observing the 2,600th anniversary of Jimmu’s ascension, never got past the blueprint stage. The land was eventually utilized for the 1964 games, and still functions as a public park and for holding various sporting events.

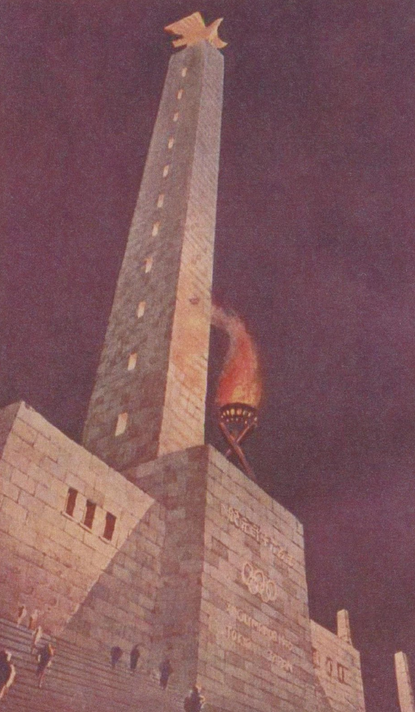

Artist’s conception of a tower, planned for Komazawa Olympic Park but never built.

A more modest structure remains there from the 1964 games.

The Marathon, scheduled for September 29 — the final day of the track and field events — would probably have followed a route from the north exit of Komazawa stadium to the ring road (now Kan-nana Dori) at Daitabashi, crossing Koshukaido (National Highway 20) and making the turn-around in the vicinity of Inokashira park.

Not surprisingly, many Japanese saw the hosting of the games as a once-in-a-lifetime business opportunity. By September 1936, a small publisher was selling a 60-page pamphlet for merchants and concessionaires titled “300 million yen will be spent! What to do to turn a profit?” (Yoza 1936)

Based on estimates of ¥150 million in expenditures at Los Angeles in 1932 and nearly ¥200 million by Berlin in 1936, the writer predicted the “Olympic economy” in 1940 could expect an economic windfall of over ¥300 million.

“While Tokyo is inferior to the other two cities in terms of its geographic location,” Yoza writes, “it will be supported by ‘excitement over Asia’ and thanks to advantageous foreign exchange rates for visitors, the total number of visitors should exceed both Los Angeles and Berlin.” (Yoza 1936)

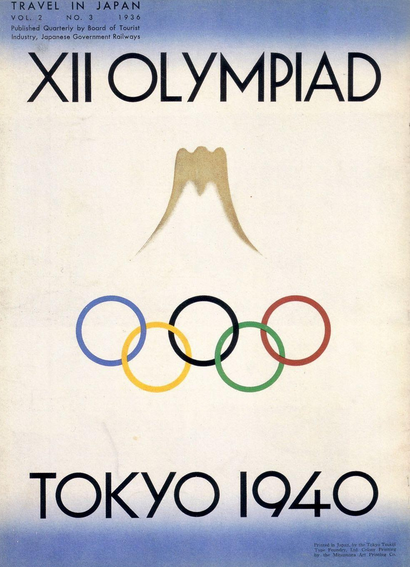

Cover of English-language magazine published by the Japanese Government Railways.

Infrastructural projects would include construction of a new city hall, refurbishing of Tokyo’s central rail station, expansion of the subways, hotels, theaters, etc., as well as “development of radio, television and airlines.”

The biggest customers of all would be Japanese themselves, who, “excited by the festival atmosphere” would account for expenditures estimated at ¥50 per person, realizing a total of ¥50 million.

English-speaking tour guides could expect to earn ¥15 per day or ¥450 per month, and demand could be expected to soar at toy stores, goldfish shops, sign makers, film development laboratories, laundries and manufacturers of flags and banners.

Road to Ruin

The sequence of events that led to the 1940 games’ forfeiture can be said to have begun on July 7, 1937, when Japanese and Chinese troops clashed at the Marco Polo Bridge southwest of Beijing. The scope of the war quickly widened. By August a large part of Shanghai’s Zhabei district was devastated as the two sides engaged in a ferocious three-month long battle, similar to what was to occur years later at Stalingrad.

The U.S. and other democracies soon raised the issue of a boycott. The New York Times, in an editorial dated June 20, 1938, voiced strong opposition to U.S. participation. The tone clearly reflected a sense of remorse for the U.S. having, against better judgment, sent a team to Berlin two years earlier. “When our athletes went to Germany in 1936,” it asserted, “they lent themselves…however, unwittingly, to Nazi propaganda.”

“Peace and good-will will not be promoted by the Tokyo meetings,” it continued, “even though, as one Japanese spokesman put it, ‘the struggle in China has no bearing on the situation; the conflict is being carried on far away.'”

Moreover,

“When Governments appropriate money for the Olympiads, as Germany did in 1936 and Japan is doing in preparation for 1940, and when the same Governments at the same time deliberately and arrogantly offend against our common humanity, sport does not ‘transcend all political and racial considerations.’

If [our athletes] go to Japan in 1940 they will seem to be bestowing approval on a Government which has lost the right to command it.

It is hypocrisy, or worse, for us to make any gesture that conceals a natural horror and revulsion. We have the opportunity, by refusing to take part in the twelfth Olympiad, if it is held in Tokyo, of expressing a moral judgment which hurts none except those whose consciences are, or ought to be, sensitive.”

In July 1938, the Japanese government made the anguished decision to forego both the Tokyo and Sapporo Winter Olympics, which had received final approval at the 37th IOC Session in Cairo four months earlier. In a terse dispatch from the vice minister of health and welfare dated July 15, then-Tokyo Mayor Kobashi Ichita was informed, “While it had been desirable for the 12th Olympiad to be held…current circumstances require full physical and mental effort be devoted to achieving [national, i.e., military] objectives…and thus the games are to be halted.” (Hashimoto 2014)

Aside from the loss of face, the drain on the Tokyo and national finances caused by the games’ cancellation was considerable. An article titled “How much was wasted by cancellation of the Olympics?” that appeared in the September 1, 1938 issue of Hanashi magazine, produced a rough calculation. These included the sending of delegations to Los Angeles and Berlin, ¥1.5 million; promotional outlays by Tokyo City, ¥3.5 million (Helsinki actually outspent Tokyo in a losing cause, spending the equivalent of between ¥4 to ¥5 million.) Setting up of a temporary office in on the 4th floor of the newly constructed South Manchurian Railway Building in Toranomon, budgeted at over ¥3 million in 1937 and ¥4.5 million in 1938, of which only four months were utilized, so perhaps ¥130,000. Another ¥1 million was estimated to have gone into advertising and public relations activities. (suggested conversion rate for Japanese yen figures cited above is approximately US $17.70 to one Japanese Yen)

Private businesses also suffered financially. Tokyo in 1938 had only 1,955 hotel and ryokan rooms deemed suitable for foreign visitors. Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel had issued additional shares of stock to fund a new 8-story wing, to be erected adjacent to its 280-room Frank Lloyd Wright edifice that opened in 1923—and the new wing would have boosted its total rooms to 500. Designers were already concerned that with steel and concrete being diverted to the war effort, its construction would have been next to impossible, and the project was terminated. (Imperial Hotel 1990)

The IOC’s initial reaction was to transfer the 1940 games to Helsinki; but with Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, the 1940 games were cancelled for good.

As events were to transpire, Japan was to host a smaller event in the summer of 1940. The East Asian Games consisted of 17 events spread between June 6-9 in Tokyo and in June 13-16 in Nara and Hyogo prefectures. About 700 athletes representing some seven countries and regions participated: Japan, the Philippines, China, Manchukuo, Mongolia, Thailand and Hawaii. (The Hawaiian contingent was made up of ethnic Japanese). (East Asian Games 1940)

Two months before the cancellation of the Helsinki games, Japan had fielded what was, up to that time, its strongest swimming squad ever. Of its nine members, four appear to have been killed in battle. An article in the Tokyo Shimbun (Dec. 9, 2019) cited former track and field Olympian and Hiroshima City University professor emerita Sone Mikiko, as having determined that at least 28 (but possibly more) Japanese Olympic athletes lost their lives in World War II and its immediate aftermath. The only female, diver Igawa (nee Ohsawa) Masayo, worked in Manchuria as a typist for the Army and died of illness in 1946. The numbers of those Sone traced, broken down according to the games in which they took part, are as follows: Antwerp (1), Paris (1), Amsterdam (1), Los Angeles (3), Lake Placid (Winter games) (1) and Berlin (21).

References

Hashimoto, Kazuo, Maboroshi no 1940 Tokyo Orinpikku, Kodansha, 2014

Japan Racing Association. Transcribed from archival materials by author.

Imperial Hotel (1990) 帝国ホテル百年史 : 1890-1990 (Imperial Hotel 100th anniversary 1890-1990) Tokyo: Imperial Hotel, Ltd.

Wikipedia, “1940 East Asian Games.”

Tokyo Shimbun (2019) series titled Orinpian no ihin (articles the Olympians left behind), December.

Uemae Junichiro,1976. Tokyo Orinpikku Showa 15 nen, Shukan Bunshun, July 22

Yoza, Masato, 1936. Sanokuen no Kane ga Ochiru! Nani wo shite ichimoke suru ka? Tokyo: Dokusho Shimbun-sha.