Abstract: This essay reflects upon the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, explaining the socio-political context in which the Games were planned. How far has Japan come since 1940? There are issues and problems that were apparent around 1940 that have not been fully resolved. Contemporary Japanese society seems to embrace racial diversity on an unprecedented level, most visibly in sports. This embrace, however, seems to be limited to cases where the racial difference is visible and excludes those of mixed Asian ancestry due to unresolved historical issues.

Most people see the 2020 Tokyo Olympics as the second Olympics in Tokyo, and some are hoping that the economic miracle and social transformation symbolized by the “first” Olympics of 1964 will be repeated. In the nation’s collective mind, the 1964 Games evoke only positive memories: recovery from wartime destruction and the achievement of new levels of modern life, exemplified by the first ever satellite TV broadcasting of the Games. What might not be as well-known is that the 2020 Olympics are indeed the third Olympics that were ever planned in Tokyo. The first were to have taken place in 1940, coinciding with an important national event: kigen nisen roppyakunen, the celebration of the 2600th year since the enthronement of the legendary first emperor, Jinmu. The 1940 Olympics—officially the Games of the XII Olympiad—were cancelled, along with another coinciding event, an international Tokyo Exhibition (Tokyo tenrankai), due to increasingly serious global political and military conflicts at the time, including Japan’s war with China that began in 1937.

With the 2020 Olympics imminent, this essay reflects upon the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, explaining the socio-political context in which the Games were planned. How far has Japan come since 1940? The essay at the end provides an insight on the country’s transformation in the past eighty years. There are issues and problems that were apparent around 1940 that have not been fully solved today.

***

The history of sports in Japan cannot be separated from its modernity. The ideas of exercise and sports were Western imports. It was in the Meiji period, as early as the 1870s, that the Japanese government stressed the importance of physical exercise especially among school children and youth, and exercise was understood as an important part of Japan’s modernization project to “catch up” with the West (Abe, Kiyohara, and Nakajima 1992). Japan first participated in the Olympics in 1912, competing on the international stage. Along with the introduction and development of racial hygiene and eugenics in scientific discourse, the government began initiatives to improve the physical as well as “spiritual” well-being of its citizens, aiming to “better” the Japanese race (Nihon minzoku). Not only men but women too were evaluated through this lens: the Miss Nippon contests administrated by Asahi Newspaper in the early 1930s selected winners based on height and athletic capability (Robertson 2001). This period saw the creation of a number of Japanese-style paintings that show women engaged in athletic activities, such as skiing, which had never previously been a subject matter in pictorial art.

Physical training was meant to promote a sense of collectivism, conformity, and even “national spirit,” not to develop individualistic interests. This tendency became more pronounced around the time of the Manchurian Incident in 1931. A large number of sports events were organized both nationally and locally by state-sanctioned organizations such as the Japan Sports Association (Zen Nippon Taisō Renmei), which was established in 1930 (Sakaue and Takaoka 2009, 409). These events, called taisō taikai (exercise conventions) or taisō sai (exercise festivals), were supported and sponsored by the Ministry of Education, local governments, schools, and mass media. School children, teachers, and factory workers participated in the events, and in 1934 alone, over three million people in 7520 different organizations in thirty-five prefectures were involved. It was understood that exercise (taisō) was best done by large groups of people rather than by individuals, and a number of different styles of exercise to be done collectively were created—kokumin taisō (national exercise), kenkoku taisō, (nation foundation exercise) kōkoku shinmin taisō (imperial citizen exercise), kokutetsu undō (national railroad exercise), sumō taisō (sumo exercise), and Kumamoto ken taisō (Kumamoto prefecture exercise), to name a few. Ultimately, with the escalation of Japan’s military involvement in Asia, some of these exercises began to include “throwing a hand grenade, bayonet drill, running in armor, and running carrying a sandbag” (Abe, Kiyohara, and Nakajima 1992, 17).

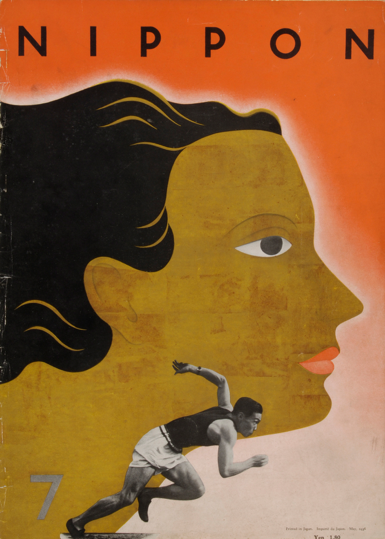

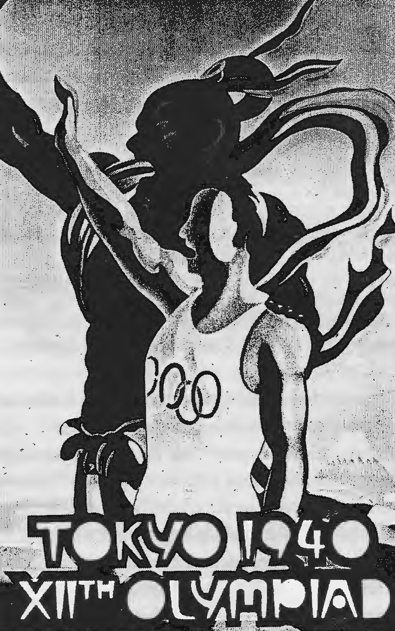

Tokyo was selected as the site for the 1940 Olympics in 1936. By this time, Japan had organized various international athletic events: the third Far Eastern Championship Games (Kyokuto senshuken kyogi taikai) took place in Tokyo in 1917 (Hübner 2016). Graphic designer Takashi Kono’s cover of the magazine NIPPON, published June 1936 in the midst of Japan’s campaign to host the Olympics, is a visually compelling montage of a Japanese man sprinting against the background of a dark-skinned, curly-haired woman facing the same direction (Figure 1). Between 1936 and 1938, the year the IOC decided to award the Games instead to Helsinki in Finland, the country was already preparing for the event. The government planned a building of a stadium that would accommodate a hundred thousand visitors (which later became Meiji Jingu Stadium and was used during the 1964 Olympics), and Wada Sanzo, a Western-style painter, designed an official poster (Figure 2) The poster juxtaposes an athlete raising his right hand with a wrathful Buddhist figure Nio. The artist uses a clearly modernist visual language of abstraction and stylization, reducing both figures to forms and repeating the wavy lines of the bodies’ contours to create strong graphic impact.

|

Figure 1. Takashi Kono, Issue 7 of Nippon magazine, 1936. |

|

Figure 2. Wada Sanzo, Poster for the 1940 games. |

Along with the Olympics, there was another important international event that was planned to take place in Japan that year: The Tokyo Exhibition. It was conceived as a World’s Fair, and for this event as well, the state made significant investment. The Wolfsonian in Florida houses a few postcards that portray building plans designed for the occasion (Figure 3). Monumental buildings in these postcards, like the graphic designs for the Olympics, use a modernist visual language that prefers clean lines, geometric abstraction, and minimal decoration, which make the designed buildings resemble the architecture in other fascist nations of the time: the 1932 Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution in Italy and the Valley of the Fallen in Spain (1940-1959) (Schnapp 1992).

|

Figure 3. Tokyo Exhibition, ca, 1940. Postcard. The Wolfsonian. XC1993.345.5 |

1940 was a particularly important year for Japan. Based on the Shinto myth from the ancient Nihonshoki, it was believed that Emperor Jimmu, a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, established the country in 660 BCE. The government had started planning a national/imperial celebration of the anniversary in 1935, and in November 1940, there were thousands of citizens gathering around the Imperial Palace, and hundreds of events, including theater, performance, exhibitions, and festivals, taking place on a local and national scale (Ruoff 2014). While the Olympics and the World’s Fair did not materialize, the imperial celebration became one of the most important political events involving various aspects of society and culture of this time.

All three events—the Olympics, World’s Fair, and the imperial celebration—were planned in the context of Japan’s colonialism/imperialism and ultra-nationalism (or, as some call it, fascism).

Japan was an imperial nation with colonies in Taiwan and Korea, and had advanced militarily into Manchuria since 1931. The Manchurian Incident spurred a backlash from Western democratic nations, and Japan left the League of Nations in 1933. In fact, the Olympics and World’s Fair were planned by the Japanese government as a part of its international cultural diplomacy in order to ameliorate the relationship with the Western democratic nations, especially Britain and the United States. However, Japan started a war with China in 1937, which strained its relationship with the Western Allies, and in this context, both the Olympics and the World’s Fair became impossible. The Tokyo Olympic Games were cancelled, and the Tokyo Exhibition postponed.

During the war, the Japanese government considered the country a sacred one ruled by a divine emperor, and the national and racial/ethnic identity was at the core of the country’s wartime ideology. Kokutai no hongi, published in 1937 by the Ministry of Education, defined Japanese citizens as organically bound to the imperial family and thus responsible to defend the nation to protect the Emperor. The Japanese were understood to be unique, spiritual, and morally superior to the materialistic, individualistic, and “selfish” Westerners (mostly British and Americans), who were associated with individualism, liberalism, as well as communism. The wartime Japanese state advocated the recreation of pre-modern Japanese customs along with aspects of modern science (such as scientific racism) and technology, and justified violence against both Western democratic nations and its Asian neighbors. By around 1935 those who challenged this line of thinking were being imprisoned.

Local communities were tightly connected, creating a surveillance neighborhood system, which virtually eradicated the space for private lives. Women were encouraged to reproduce, giving birth to future soldiers. They were reduced to their reproductive capacities by the ume yo fuyaseyo (produce more babies and increase the population) policy and the establishment of Mother’s Day in 1931, and mothers were expected to feel honored to sacrifice their husbands and sons to the nation.

There were complex, competing, and contradictory theories about the differences/similarities between Japanese and other Asian people. The colonial subjects in Taiwan and Korea became “Japanese,” although they were never treated equally. The Olympics were not separable from this political reality: it is well known that a Korean publisher edited a photograph of Sohn Kee-chung (1912-2002), a Korean athlete who competed as Japanese and won a gold medal in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, for Korean audiences, removing the Japanese flag from his uniform.

***

The 2020 Tokyo Olympics—the Games of the XXXII Olympiad—will take place in a completely different context. The Games coincide with the celebratory mood of Emperor Naruhito’s enthronement, but unlike in 1940, Japan is now (in theory) a democratic country that guarantees freedom of speech and thought, and the emperor is now understood to be a symbol of the country, not a divine political leader citizens are obligated to die for. The relationship between Emperor and citizens has changed dramatically. Emperor Akihito, who succeeded Emperor Hirohito in 1989 and became Emperor Emeritus in 2019, established a new image of an emperor who serves the citizens, regularly visiting those undergoing hardship, such as victims of natural disasters, and publically expressed remorse for those in Asia and other countries who were affected by Japan’s colonialism, even as right-wing politicians maintained wartime narratives and justifications for the country’s violence.

When Naruhito acceded to the Chrysanthemum Throne in 2019, media attention focused on his wife, Empress Masako. Born Owada Masako, she has an impressive familial, educational, and professional background: her father is a former jurist, diplomat, and law professor, and she has lived in Russia, the United States, and England, and studied at the University of Tokyo and Harvard University, worked as a diplomat, and speaks Japanese, English, Russian, French, and German. She (reluctantly) married the then Crown Prince in 1993, which was nationally celebrated, but famously suffered from emotional distress resulting from the restricted freedom of an imperial family member, a miscarriage that was made public, and intense pressure to produce a male heir: the current law does not allow a woman to succeed to the throne. Ultimately diagnosed with an “adjustment disorder,” Princess Masako had practically disappeared from public life until Naruhito’s enthronement (Rich 2019). Her story represents both how far the country has come—women can pursue higher education and professional careers if they desire—and how patriarchal it remains—women are in the end reduced to the role of reproduction, which uncannily reminds us of women’s role ca. 1940. Despite Prime Minister Abe’s initiative of “womenomics” to create a society where “women can shine,” feminist scholar Ueno Chizuko’s recent speech at the graduation ceremony at the University of Tokyo and the #MeToo/#KuToo movement make it clear that much work needs to be done to improve the fundamentally male-dominated Japanese society for women (Masutani 2019).

Contemporary Japanese society seems to embrace racial diversity on an unprecedented level. There are countless half-Japanese celebrities and models, though this does not by any means suggest they do not encounter discrimination in their daily lives. Racial diversity is most visible in sports. Japanese-Haitian tennis player Naomi Osaka has been hailed nationally (and globally), and Japan’s national teams in track and field, rugby, and basketball also include players of mixed race. This acceptance of racial diversity, however, seems to be limited to cases where the racial difference is visible: those who are half-Korean or half-Chinese, for example, do not necessarily receive same kind of favorable attention. There is still discrimination against Zainichi Koreans (the permanent ethnic Korean residents of Japan), if not against K-Pop stars, and recent disputes between Japanese and Korean governments over compensation for wartime forced labor indicate that Japan has not solved its issues with race/ethnicity that are historically rooted and require critical reflection.

Bibliography

Hübner, Stefan. Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913-1974. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2016.

Ikuo Abe, Yasuharu Kiyohara, and Ken Nakajima, “Fascism, Sport and Society in Japan.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 9.1 (1992): 1-28.

Masutani, Fumio. “Sexist Thinking Is Everywhere, Even at Todai, New Intake Warned.” The Asahi Shimbun. April 13, 2019.

Rich, Motoko. “A Princess in a Cage: The Survival of Japan’s Monarchy Rested on Her Shoulders. No One Ever Let Her Forget It.” The New York Times. April 29, 2019.

Ruoff, Kenneth J. Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014.

Sakaue, Yasuhiro, and Hiroyuki Takaoka, Maboroshi no tōkyō orinpikku to sono jidai: Senjiki no supōtsu, toshi, shintai [The Tokyo Olympics That Was Never Realized and Its Time]: Sports, City, and Body]. Tokyo: Seikyusha, 2009.

Schnapp, Jeffrey. “Epic Demonstrations: Fascist Modernity and the 1932 Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution.” Fascism, Aesthetics, and Culture. Edited by Richard J. Golsan. London: Harnover: UPNE, 1992.