Abstract: My daughter was born in March during COVID-19. Because of the pandemic, my baby cannot meet her grandparents who live overseas, as Japan has implemented an entry ban for most foreign nationals. It should have been a special time for my family, but now there is no way of knowing when we will be able to see each other again. As a foreigner in Japan and a new mom, it is a very challenging time. All I can do is wait for the Japanese government to lift the travel bans and hope that the COVID crisis will end soon so that I can be with my family again and introduce my daughter to them.

I am a Taiwanese living in Tokyo with my American partner and daughter. My daughter was born in Tokyo this year on March 4th, during the pandemic. She is the first grandchild of both my partner’s and my parents. Months before the due date, both of our families had begun to plan to come from overseas to see the baby girl. Unfortunately, their trips have been postponed because of COVID-19. As the pandemic spreads all over the world, many countries have imposed travel bans that prevent our families from coming to Japan, and if we went to visit ourselves and left Japan, we as foreigners would not be able to come back. The pandemic has not only brought us anxiety concerning our health, especially for our newborn, but also disappointment that we are unable to be with our families in this special time.

I remember back when I invited my sister and cousin to my apartment for Chinese New Year dinner in January, I did not think that the virus was such a big deal. In fact, when my cousin showed up to my apartment wearing a mask, I asked him if he was sick and he told me that he was trying to protect himself from the virus. I kind of made fun of him and thought it was unnecessary, because at the time there was only one confirmed case in Japan and Japanese media claimed that the virus was just like other flu. However, since I saw my cousin take it seriously, I started following more information mainly from Taiwanese media rather than Japanese, as the Taiwanese government seemed to be employing more caution than the Japanese government.

In fact, Taiwanese media had begun focusing on the coronavirus following the government establishment of the Central Epidemic Command Center on January 20th. It is worth noting that there were no cases in Taiwan yet when the Command Center was established. As of January 20th, only four countries had confirmed cases – China, Japan, Korea, and Thailand. The virus was not even officially named yet, but the Taiwanese government took swift action because it had learned its lesson from the SARS outbreak in 2003. I was about nine years old back then, and I can remember we had our temperature taken at school everyday. My mother bought a whole bunch of N95 masks and made me wear the mask every day. Although I was just a young child, I could tell the situation was serious. Now in 2020, as the coronavirus spreads, Taiwan does not want to repeat history.

As early as January, the Central Epidemic Commander Center in Taiwan announced that people from Hubei province in China would not be granted entry to Taiwan, and soon after, in the beginning of February, the ban expanded to all Chinese citizens. I watched from social media that many of my Taiwanese friends cancelled their travel plans and avoided going to the airport, since it would be a high risk place for infection. Meanwhile, in Japan, no one that I knew seemed to be bothered by this new type of virus. Masks did sell out in many stores in Tokyo starting in early February, but when I spoke to one of my Japanese friends about it, he said that from what he could see it was not the Japanese who were buying masks, but Chinese tourists who were stocking up as much as they could before they returning to China. On the streets of Tokyo, the majority of people did not start wearing masks until the state of emergency was announced in April.

|

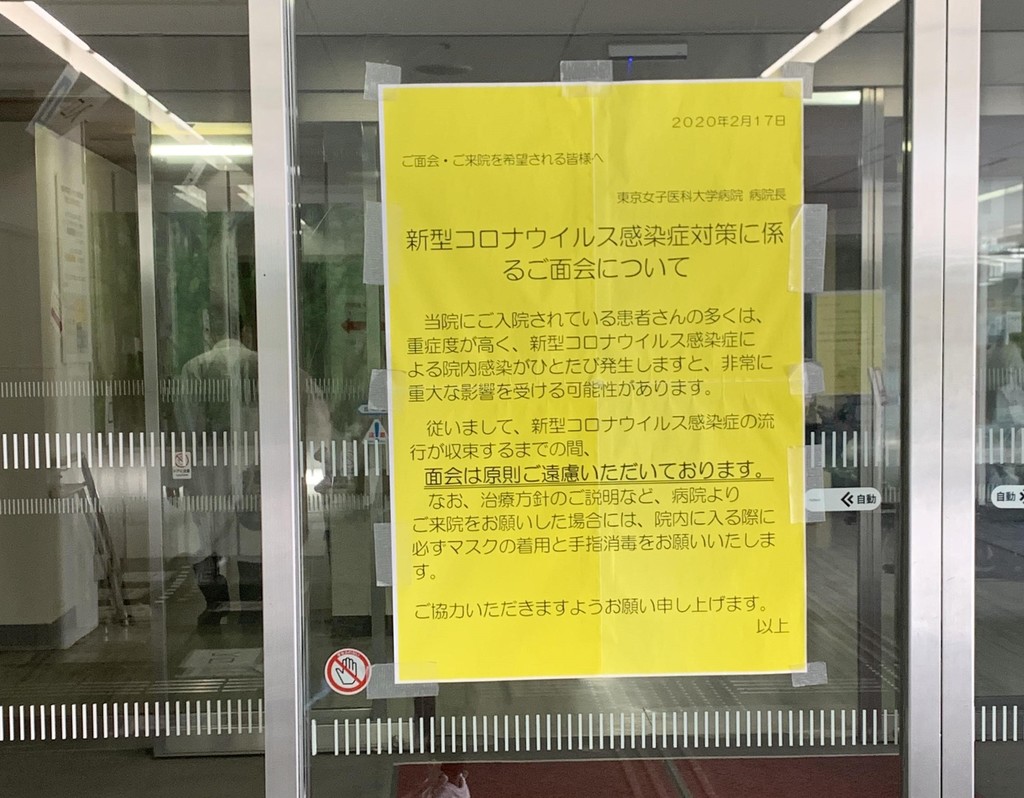

Although the Japanese government was slow at responding to COVID-19, my hospital has prohibited visitors to patients from February 17th. |

Before mid-March, life was still quite normal in Tokyo other than masks and toilet paper being sold out everywhere. In the final weeks of my pregnancy, I was still out everyday, going to restaurants, the gym, and the hospital for checkups. Things only started to change a couple of weeks before I was scheduled to give birth. My hospital asked all visitors to wear a mask and I was told in my last prenatal checkup at the end of February that visitors would not be allowed during my stay due to the coronavirus. They could only make an exception for my partner to be there during labor. This is when I started to feel my life become affected by the pandemic, and I gained the sense that I needed to be more cautious not only for myself, but also for my baby.

|

The booklet I received at the hospital after my baby was born. New moms have to bring the booklet to the classes with them at the hospital. |

Regarding the policy prohibiting visitors at the hospital: at first I did not think it would be a big deal, but it turned out to be quite difficult for my partner and me. In Japan, women stay at the hospital about one week after birth. So, it was not just for a couple of days that the baby’s dad could not see her after she was born. It was difficult for me, because in that one week I was still recovering and, at the same time, had to learn how to take care of the baby. It was more like a new mom bootcamp and not exactly designed for those who want to rest after birth since there were classes to take and we were encouraged to have our babies stay in our room with us. I was exhausted every day, so when my baby and I were finally discharged from the hospital, I was overcome with relief.

My baby girl and I were discharged on March 10th, about one week after she was born. I told my mother and mother-in-law that we would be quite busy in March, since we had to apply for a visa for the baby to stay in Japan as well as apply for her US citizenship (the process ended up taking longer than usual due to COVID-19). We decided that it would be better if the grandparents could come visit in April or May. At the time, my mother-in-law was planning to come to Japan from the US in April, while my mom booked her flights from Taipei to Tokyo in May. Although my mom went ahead and booked the flights, she was worried that she would have to cancel. We watched on the news as the number of confirmed coronavirus cases in Japan continued increasing in March. In response, the Taiwanese government asked everyone who traveled from Japan to Taiwan to quarantine for 14 days. Around the same time, the coronavirus began spreading rapidly in the US and my mother-in-law was worried that she would not be able to come.

Since the pandemic seemed to be under control in Taiwan, as there were far fewer confirmed cases than in Japan or the US, I began to consider taking the baby to visit my family. Non-Taiwanese citizens were banned from entering Taiwan starting March 19th, but I could apply for a special permit for my partner and daughter who are American citizens. My daughter also is eligible for Taiwanese citizenship. Just when I thought this could work, and my family could finally meet my daughter, the Japanese government placed a ban on all foreigner entry to Japan, including long-term visa holders, from the beginning of April. This meant that if we were to leave, we would not be able to return for an indefinite amount of time. Just like many others, my family and I ended up having to change a lot of our plans due to the pandemic. We are still not sure when we will be able to see each other, as the situation continues to be unpredictable and no one knows at what point we can really say that the crisis has ended.

|

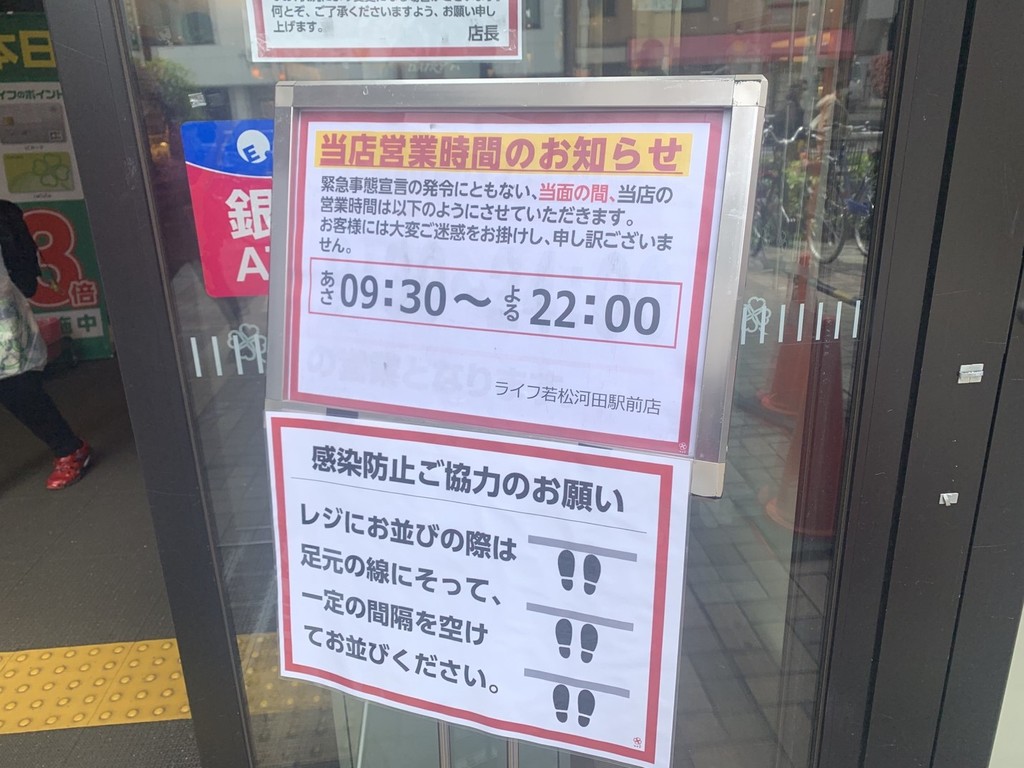

Since the state of emergency was announced, my local supermarket has shorted the hours and asked customers to keep social distance. |

Once the Olympic Games were officially postponed, the Japanese government began to take more actions in response to the pandemic. Since Prime Minister Abe declared a state of emergency in the beginning of April, my family and I have remained at home as much as possible to protect both ourselves and those around us. Having a newborn at this time makes staying home even more necessary, as I would not want to go out and bring the virus back home and get my baby girl sick. While I would like to also avoid taking my baby out in the public entirely, there are times I have no choice, for example, when I took her to her citizenship interview at the US embassy, or when we attend our regular checkups at the hospital for routine vaccinations. As a first-time mom, I was already nervous about taking care of a little human and the pandemic has only worsened my anxiety.

In late May, the state of emergency was lifted in Japan. However, the confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Tokyo have continued increasing even now in July. While the situation seems to be under control in Taiwan, I hesitate to travel because the Japanese government has not yet allowed reentry for Taiwanese and US citizens. Flying with a newborn at this time also seems too risky. It is now four months after my daughter was born and she still has not met her grandparents. The immigration authority in Japan claims that foreign residents with long-term visas can be allowed entry on humanitarian grounds, but we do not meet the criteria. As a new mom and a foreigner in Japan, it is indeed a very challenging time. There is not much I can do other than wait for the government to lift the travel bans and hope that the crisis will end soon so that my family can reunite and I can at last introduce our new addition to everyone.