Introduction

“Harvest” is a story about the aftermath of a criticality accident that occurred at the Tokaimura nuclear fuel processing plant in Ibaraki Prefecture on September 30, 1999. Hayashi first learned about the accident from watching the TV news in a hotel room in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the night before she was to visit the Trinity site where the first atomic bomb was tested. After returning from New Mexico, Hayashi visited Tokaimura where she met an old farmer who had refused to evacuate. “Harvest,” which grew out of that meeting, seems eerily prescient today, six years after the Fukushima disaster, for in it, we find the same cloud of misinformation concerning the dangers of radiation, which threatens the survival of a rural community and its way of life.

|

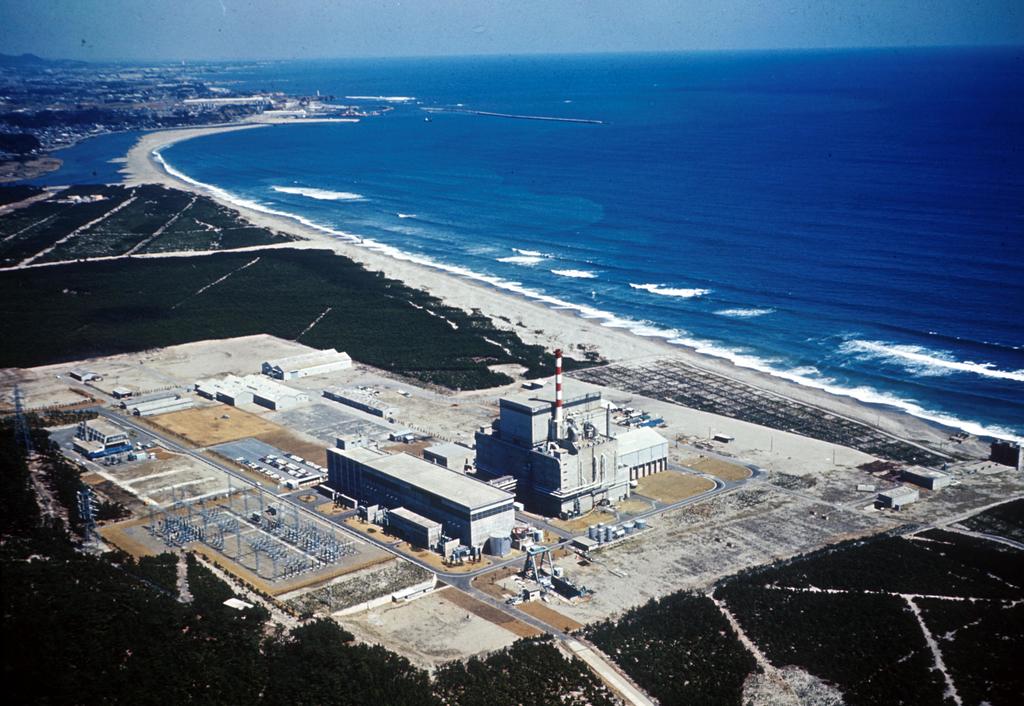

Tōkai Nuclear Power Plant |

Another parallel that might be drawn between “Harvest” and Fukushima—which is not explained in detail in the story itself—is the utter lack of concern for public safety on the part of the company that runs the nuclear power plant. If the Tokaimura accident can indeed be called an “accident,” like the Fukushima disaster, it was an accident waiting to happen. In its wake, the Japanese public was shocked to learn that the manual issued to workers at the plant was not the official government one, but rather a “back manual” (uramanyuaru) prepared by the company (JCO, a subsidiary of the Sumitomo Metal Mining Company) that placed speed and efficiency above safety. For example, whereas the government manual required that enriched uranium fuel be mixed in a dissolving tank, the uramanyuaru instructed workers to use stainless steel buckets instead, and to then pour the mixed fuel directly into the precipitation tank, rather than into a buffer tank designed to prevent the onset of criticality. On that September morning three workers poured seven buckets full—a total of 35 lbs. of enriched uranium, or seven times the amount permitted by the government manual—into the precipitation tank. After the seventh bucket, they saw a blue flash. The mixture had gone critical. The three men apparently didn’t realize what was happening, and the plant management was totally unprepared to deal with the situation.1 Two of the three workers were to die within a year of the accident. Near the end of “Harvest,” Yamada mentions one of them, a “man from the next village over” who “could die at any time.” This is presumably Ōuchi Hisashi, who died at the age of 35 on December 21, 1999. The high concrete wall around the plant that casts a shadow on two rows of Yamada’s potato plants also hides the greed, carelessness, and mismanagement that is putting all of the villagers’ lives at risk.

Like many of the Fukushima residents, Yamada loves working the land his ancestors have farmed for hundreds of years. He is not, however, a stereotypical “simple” farmer. He keeps himself informed by reading “a newspaper most of the villagers shied away from, saying it was for the ‘elite’” (probably the Asahi or Mainichi, Japan’s major left-leaning daily newspapers). He is also a war veteran. In light of this background, his first reaction to the plant’s siren—fear of a “nuclear explosion”—is intriguing. Although not sure what the siren means, he seems to instinctively sense a connection between the mysterious goings-on behind the wall that surrounds the plant and the atom bomb. This connection between the A-bomb and nuclear energy was a major concern to Hayashi late in her life, as can be seen in her last essay, To Rui, Once Again, which was recently published in translation in The Asia-Pacific Journal.

|

Hayashi Kyoko |

All of Japan’s nuclear power plants are located in rural areas, far from the urban centers that consume most of the power they generate. “Harvest” depicts the damage the plants cause to the social fabric of rural communities by creating divisions between the “big spenders” who profit from compensation payments for their land and those who, like Yamada, stick to farming. Although residents of Tokaimura were not forced to immediately abandon their land as in Fukushima, the specter of contamination makes Yamada’s future as a farmer uncertain. Near the end of “Harvest,” when asked by a reporter about the performance of government officials who ate potatoes from Tokaimura on TV to show they were safe, he bitterly replies, “…those bigwigs don’t know nothing.” These words could have been the response of any Fukushima farmer to government reassurances that “low levels of radiation” posed “no immediate threat to human health.”

A Mainichi newspaper poll taken days after the Tokaimura accident found that 70 per cent of the respondents were opposed to nuclear power.2 In addition, Yoshii Hidekatsu, then a Diet member for the Communist Party, began in 2006 (during Abe Shinzō’s first term as Prime Minister) to warn of the dangers that a massive earthquake and tsunami would pose to Japanese nuclear power plants. Unfortunately, neither his repeated warnings nor the wave of popular opposition after the Tokaimura accident was sufficient to prevent the far greater Fukushima disaster 12 years later. Abe Shinzō is now Prime Minister once again, and nuclear power plants are being restarted, one after another. In To Rui, Once Again, Hayashi calls for the publication of the names of those responsible for restarting nuclear power plants so that they can be held responsible for future criticality accidents, with no statute of limitations. Now, with the Doomsday Clock closer to midnight than it has been since the 1980s,3 her voice needs to be heard more than ever before. Margaret Mitsutani

Harvest

The sun was out, shining cheerfully. As always, the man sat in his wicker chair in the pool of sunlight outside the barn. Tearing a cigarette in half, he stuck one end into his old-fashioned kiseru4 pipe. He slowly inhaled and blew out the smoke. He was taking a short break after cleaning the spade and hoe he’d be using that day, a job that left him slightly sweaty. This was his favorite time in the morning; his dog, who knew his habits, lay sprawled at his feet. The man was seventy-eight years old. The villagers called him Old Yamada, but the neck above the collar of his camel hair shirt shone ruddy in the sunlight, and the right arm above the hand that held the kiseru, though not very long, bulged with hard muscle.

The man owned this house. His family had lived here for generations, tilling the fields, living on the land.

The dog at his feet stood up and started to bark. His master looked over at the road out front. A young man with a camera slung over his shoulder was coming this way. As the property was not fenced in, they could see everyone who went by from the yard.

A high concrete wall ran for about two hundred meters on the far side of the road. The young man had just turned the corner along the wall, coming into view from their side.

“Been a while since we’ve had a stranger,” said the man to his dog. Nodding, furiously wagging his tail, the dog howled louder than before. The man with the camera stepped into the field. “This is my land,” the old man murmured, then asked, “You a reporter?” The young man had picked up one of the sweet potatoes scattered on the well-ploughed earth, white with frost, and was pressing it with his fingers. He was apparently testing to see if it was rotten. Watching him intently, the old man called out, “Yeah, I’m going to order some potato sprouts come January.”

It had been two months since the mysterious accident behind the concrete wall. Just after it had happened, the man had pressed his nose against a crack in the wall and peeked inside. Metal pipes, twisting and turning like silver intestines connected the buildings; two or three men dressed in baggy white coveralls had been walking among the pipes. He had been staring directly at the site of the accident.

The potato in the young man’s hand was one Old Yamada hadn’t been able to sell due to fears about the effects of the accident. Remembering what had happened that day darkened his mood.

On the morning of the accident, the man’s son, dressed for work, had marched into the yard, calling out “Good morning” to his father. His left hand slightly raised, Yamada had returned the greeting. As he was facing the morning sun, the round neck of his T-shirt had gleamed white. A closer look revealed the dirt ground into the front and sleeves of his cotton work clothes. The clear autumn sun seemed to purify even the muddy stains.

“I’ll be off now,” said the son. His father grunted in reply, then added, “You could at least wear your Yamada happi to work, you know.” The son, now over fifty, was the boss on a construction site. His father wanted him to look like one. He hated to see his boy dressed in a purple T-shirt and green knickers pulled down below his belly button like the young kids wore.

For a time, the father had helped his son out on the construction site. That was when he had had the matching Yamada happi coats made, but he’d barely worn his ten times. He had quit after about six months on the job. “Gotta work with my feet on the ground,” was his reason. Besides, his hard, knotty hands, inherited from forebears who had worked the land for three hundred years, were not made to handle tools smaller than a hoe. Yet when it came to making ridges for planting, his were the finest in the village, the long mounds of red earth as straight and even as the teeth of a comb. He loved farming; at this moment he was gazing fondly at the dewy leaves in the potato field, now changing to red and gold, just about ready for the harvest.

The son started the engine of his light truck, parked in a corner of the yard. “I’ll be back when I get things set up. Guess we’ll be digging,” he said, pointing to the field.

It was the last day of September. In October, the frost would come. If they weren’t dug up before the ground got cold, the potatoes would go bad.

The day before, the father had pulled up a vine to see how they were coming along. He’d brought up a clump of five or six fat, purple sweet potatoes. After carefully wiping off the dirt with the palm of his hand, he had bit into one. Sticky, white juice filled his mouth, even sweeter than he’d expected. They’d be ready to harvest within a week. This year’s crop might fetch the highest price ever.

Watching his son’s truck race off, spewing black smoke, the father sat down in his wicker chair. Sticking a cigarette in his kiseru, he lit it with a match. The chair had been left out in sun and rain for so long it was bleached white, and there was a hole in the middle of the seat where the straw had rotted away. A piece of board had been laid across there.

Hearing the chair creak, the dog, whose fur was the color of withered grass, came out of his house. The dog’s name was Yamada Shiro. The name was painted in red over the entrance to the doghouse. Shiro, who was left to run free, approached the man with love in his droopy eyes to give his morning greeting. He then sank his belly to the earth, warm in the morning sun, and lay down. Shiro was a Shiba with a few other breeds mixed in. He, too, was no longer young. Both dog and man figured they would probably die around the same time. The son had never married; his mother had long ago died of a brain hemorrhage. Since then, the two men had lived together with the dog Yamada Shiro. The Shiro at the old man’s feet was number five. The five dogs had been of various colors—one black, another a reddish-brown mongrel—but as the first was white, as long as the doghouse was standing the Yamada dogs would all be called Shiro (white). So far, none had complained about it.

Let’s go, the father had said, pulling out the bicycle that was leaning against the barn wall. A jaunt down to the seashore was part of their daily routine. Shiro quickly got up and ran toward the gate. Though the whole front yard was open to the road, Shiro always passed between the stone gateposts. They couldn’t see behind the concrete wall, but it was said to be a factory where “nuclear energy” was being processed. That was the explanation they’d received before it was built: it was to be a “nuclear energy processing plant.” Some villagers had moaned, “What a god-awful thing to have to live with.” Thanks to the plant and a number of modern buildings that had cropped up along the seashore, the village population of less than ten thousand had increased more than threefold. Some were pleased with the new prosperity this change had brought. There were rumors about villagers who’d turned into big spenders with the money they’d gotten for their land. As there had been no need to buy Yamada’s land or pay him compensation, he knew nothing more about the plant than what he’d been told. Still, due to the concrete wall, one patch of his potato field was now in shadow. It was only a row or two—not enough to affect his income. Yet gazing out over his field covered with leaves, all of them playing in the morning light, had given him as much pleasure as his morning smoke. Warmed by the sun, the potatoes grew fat underground; he could almost hear them chuckling with joy.

Besides, the potatoes grown in this field got sweeter every year. As long as the drainage was good, they would grow even in poor soil, but Old Yamada wanted his to be the best. During and after the war when food was scarce, mass-production had been forced on these easy-to-grow vegetables. The ones Yamada had been given to eat when he’d come back from the war were watery, big as pumpkins, and full of tough fibers. To give his crop the earth’s nutrients, the old man had first charred plants and spread the ashes over his field, which did not drain well, then buried leaf mold to make the soil especially well-suited to sweet potatoes. Now there were confectioners specializing in cakes filled with sweet potato paste who would buy up his entire crop.

Out on the road, the old man threw a glance at the rows still in shadow, then set off along the concrete wall. Shiro ran a little ahead of him. Pedaling slowly, he could reach the shore in twenty minutes. Where the road along their field ended, Yamada and Shiro turned left at the corner of the wall. They were now on the main road traversed by buses and dump trucks. Keeping along the wall, they made three sharp right turns, which brought them to the plant’s main gate.

The employees who had come to work were just going through the iron-barred gate. A guard stood at the entrance. There were villagers he knew who had quit farming among the employees. Giving them a brief nod, the old man picked up speed as he rode past the gate. The village’s transformation had warped the relationship between those who had given up farming, and those who stuck to the land. Yamada changed his route, entering the widest street in the village. The white wall roofed with black tiles with the clear blue sky behind it seemed to go on forever. Until the plant had appeared, along with a power station and research center by the shore, this entire area had been potato and vegetable fields, in every direction. There were shrines here and there, surrounded by clumps of trees, with sea and sky spread out before them. Along the dirt path down to the beach dandelions had bloomed in spring, and through the thick rubber tires of his bike he used to feel the jolt of the hard nutmeg-yew roots throughout his body.

Every time he rode his bike down the newly paved road, the old man found himself singing a snippet from a song about Urashima Taro5 to himself: “White smoke drifted up from the box, and suddenly Taro was an old, old, man.”

Shiro, who had been running along ahead, stopped and lifted his leg to pee on another wall, also pure white. “Hold it ‘til we get to the beach!” the father called out. A bitch who had once been Shiro’s sweetheart lived here. But their relationship, too, had cooled since the appearance of this new wall. Not that he cared if it got a yellow stain. Yet the wall and the money that had built this mansion fit for a millionaire were both compensation for the land he had sweated and toiled to protect. To soil it would stain the memory of the village ancestors, the old man thought. Besides, someone might be watching. That would make for rumors that Old Yamada had it in for them, having his dog pee there on purpose. At first he’d been relieved to hear his field wasn’t on the list of plots to be bought up. Still, seeing that chilly corner in shadow every morning, he’d grown more and more disgruntled. “Might’ve been just as well if they had bought out my field,” he’d grumbled to other farmers. With successive retellings, this complaint had taken on more than a touch of greed, and rumors of Old Yamada’s desire for compensation money had spread through the village.

“Things get all tangled up,” he sighed to himself, then to Shiro, who was now peeing against the white wall, “Even you’re not free anymore.”

When he’d returned, Old Yamada sat down in his wicker chair again and smoked the remaining half of his cigarette. “Time to get started?” asked the son who was already back, emerging from the barn with a hoe over his shoulder. His father took off his watch and placed it on the chair. It was just past 10:30. That’s when it happened. Shiro, who’d been lying down, stood up, his ears pricked and, after one bark to alert his master, started growling deep in his throat. There was no one on the road. Thinking the dog might have heard far off footsteps, the old man looked over that way. No one. “What’re you on about?” asked the son, tapping Shiro on the nose. The dog’s howls grew more high-pitched. He had his front paws planted firmly in the earth, ready to attack. The howling continued. What he was howling at was not so clear. Gathering up the potato vines that had spilled out onto the path, father and son looked up. If there was something wrong, it should show in the sun and sky. Yet overhead was the same clear blue Old Yamada and Shiro had seen on the way to the shore.

“That’s a siren, isn’t it?” asked the son, listening carefully. The two men looked over at the concrete wall. The siren seemed to be coming from inside. The pine branches that rose higher than the wall seemed to scratch against each other as they swayed. Pulling the vines together to make it easy to dig up the potatoes, the son said, “It’s a siren all right.” “An alarm?” his father asked. They looked toward the power plant on the shore. Both sky and sea were silent.

“Shiro, what’s going on?” the father asked. “There’s some commotion beyond the wall,” the son replied, sure of himself now. Another siren sounded from the main road. An ambulance? The two exchanged glances. A patrol car followed behind, its siren blaring.

“I’ll go see,” said the son, stepping over the mounds of earth out onto the road. “Don’t,” the father said, more sharply than usual, “what if it’s a nuclear explosion?”

“An explosion? You think they’re making bombs at the plant?” laughed the son. Though he’d said “nuclear explosion,” the father himself wasn’t sure what that meant. According to rumors he’d heard, an accident at the plant would mean big trouble. The two men went inside and turned on the television. It was now past noon. “Says on the radio we should get out,” said the son. They heard a voice through a loudspeaker out on the road. Stay inside, it said. As the pitch of Shiro’s howls rose higher, they heard a car stop in the front yard.

Men got out calling, “Is there anyone here? All residents in this area should prepare to evacuate.”

“Was there an accident?” asked the son, who had gone out to look. “I don’t know, but you’re to wait inside for further instructions,” replied a man wearing glasses.

“Was it a nuclear explosion?” called the father from inside. “Did you hear anything like that?” another man asked.

“Nope,” answered the old man, shaking his head, “but Shiro must have—he’s been howling like a maniac.”

“Everyone living within three-hundred fifty meters is being advised to evacuate,” said the man with the glasses. “Three-hundred fifty meters, you say? Then it must be the plant—that’s right next door, y’know. Stay in all day? When I’ve got potatoes to dig?” the father said. “You’ll just have to sit tight today, and listen to the warnings on your shortwave radio,” said the man in the glasses.

After the men had left, Yamada brought Shiro into the earthen entranceway. His son shut the door.

“Always said this village didn’t need that plant. I was against it from the first. It’s nice and dry today—harvest weather,” the old man grumbled on his way out the door. “Better stay inside, nuclear means radiation—that’s the only thing it could be, if there’s been an accident. You can’t see it, but if there’s been an explosion, that means we’re run through with radiation, Dad—like an X-ray, only much stronger,” said the son.

“That’s why we gotta dig, can’t just leave the potatoes to rot.”

“We’re not leaving them to rot, they might be safer in the ground, you know. We’re just waiting ‘til we know how bad the accident is.” Might be something to that, thought his father. Once they were out of the ground, potatoes have to be left in the sun until the earth stuck to their skins dries out. If there was radiation floating through the air around here, they’d be safer underground. But a farmer has to move when the weather’s right; it’s not so easy to “wait and see.”

The old man stood in the hall, looking out at the potato field. A wind had come up. The leaves were waving in the wind, showing their undersides. Deep red veins stood out, almost brazen with life. The ripe potatoes underground would be about the same color, waiting to come out into the light. Thinking of how they must feel, the old man could hardly breathe. He went back to the television.

New information was being broadcast; pictures of the accident happening right outside their house flashed on the screen. They were right beside it, yet had to rely on the TV—a strange feeling. What’s more, every reporter on every station was saying exactly the same thing. Which left no room for wild rumors. Nor did it give them any basis for comparison, which might have helped them judge what was really going on.

“It appears a criticality accident may have occurred,” the announcer said. Two or three employees had received high doses of radiation. The face of the guard he’d greeted that morning flashed into the old man’s mind. “He was at work then,” the son said, naming a childhood friend.

The announcer, along with an expert, started explaining what a “criticality accident” was. No matter how many times he listened, the old man didn’t understand.

“I don’t really get it either, Dad, but on TV they’re saying that a ‘criticality accident’ is when ‘uranium fuel under certain conditions gathers in one place, causing nuclear fission to occur, creating a situation in which there is a continuing nuclear reaction; in other words, a chain reaction that causes radiation and extreme heat to be released,’ ” the son explained, parroting the announcer word for word.

“Did those guys get burned bad?” asked the father. “Must have, since they said ‘extreme heat’,” answered the son.

The scene changed to elementary school children returning home in single file along the now deserted road through the village. The children, all wearing yellow caps, waved and made faces for the camera as they walked through the sunlight. How much had been explained to them? Everything looked as calm as it had been the day before. Looking at the police who were guiding the children along, the old man said, “They’re not from around here.”

“Folks are coming in from all over—things must be pretty bad,” said the son.

The elementary school was to the west of their house.

“The school’s down wind, ain’t it,” the father said.

As the sun was setting, another car stopped in front of the darkened yard. Two men got out. “Please get in the car,” said the one wearing a smart jacket. They were to be taken to the community center, the designated location for evacuees, or to a clinic where they could receive a preliminary health check. “I believe you are aware that residents within three-hundred fifty meters have been advised to evacuate; there appear to be high levels of radiation in this area, so we would like you to be checked just in case.”

“Have they got that criticality accident fixed yet?” asked Yamada, standing on his front stoop. “We are to take you a safe place and see that you receive a health check; that’s our job, and we have not been told anything else. About a hundred people from this village have already been evacuated,” said the man in the jacket. “We will also be taking samples from your yard—soil and rocks—in a few days, so I hope you will cooperate,” said the other man.

“Is that your field?” he asked. In the dark, the mounds looked like waves. “We will also need to take some dirt, vines, and potato samples to examine,” he went on. “I’m worried about our field, so go right ahead,” the son replied. This must be the investigation for contamination they were talking about on the news. If the earth in this area and the vegetables grown in it were contaminated with radiation, would they have to get rid of the potatoes they harvested? This was what worried his father.

It was unthinkable. He’d cared for this crop for five months now; ever since he planted the shoots last May he’d been looking forward to the harvest. “If we don’t get them out of the ground in the next two or three days they’ll go sour,” he said. “The examination should be over soon; you will just have to wait for the result,” said the man in the jacket, adding, “Please get in the car now, and bring enough clothing for two or three days.”

“I’m not going,” the father announced, sliding the lattice door shut. “Once his mind’s made up there’s no changing it,” said the son. “Well, we can’t force him,” said the other man.

After his son had left carrying his clothes in a paper bag, the father planted himself in front of the TV. “It’s radiation, Dad. You can’t see it,” the son had said in a vain attempt to convince him to come along for a health check, but the old man had stubbornly repeated, “I’m not going.”

The dark room, lighted only by the TV screen, brightened now and then with the headlights of a passing car. Normally there was no traffic on this road at night. Peeking out the window, he saw five or six broadcast vans lined up along the concrete wall. He switched the channel to the station whose name was painted across one of the vans. “On the spot report,” it said in a corner of the screen. That van parked outside must be recording the scene he was watching now. As his son had said, in addition to the radiation from the plant, they were now surrounded by a network of radio waves.

The father stood in front of the television and waved his arms. Perhaps this would disrupt the air and the radio waves flying through it, making static on the screen. If he could break up the picture, he’d feel he was really here, right on the scene. These news broadcasts that flew over his head were hard to take, when he and his neighbors were the principal actors in this drama.

The broadcast vans lit up the road outside so that it looked like the night of the village festival. Groups of reporters had pitched little vinyl tents. Covering the accident was going to be a long-term project. The father clicked his tongue. As long as he’d been in this village, he’d never seen a night as busy as this one.

No matter what, tomorrow I dig, he muttered.

His son did not come back the following day. In addition to the check for surface contamination, he had requested a blood test. Old Yamada could work the field by himself. He got ready and went out into the yard. Emerging into the chill air, he gasped in surprise. Last night there had been two or three vinyl tents; this morning they filled the road like umbrellas on a rainy day. There were more vans, too—the whole country had focused its attention on this tiny village. He sighed in amazement.

During the war, he had been taken prisoner on a southern island. He hadn’t seen a single Westerner since then, but this morning there were several, moving in and out of the vinyl tents. So it wasn’t only Japan. The whole world was watching this village. After hesitating a moment, he sat down in his wicker chair, facing the reporters. A few looked back. Pretending not to notice, he put half a cigarette in his kiseru and lit it. What to do in the midst of all these goings on. . . Of course he intended to harvest potatoes. Still planning to, he was taking his morning smoke before starting work. But people from the press were milling around his field. He wanted to show them a farmer’s spirit, but this bristling, eerie atmosphere gave him pause. Besides, he didn’t know how badly the earth and the potatoes had been contaminated in one night. He was becoming more and more worried about whether he’d even be able to plant potato sprouts in this field next year. The day had come when the village fishermen had all given up and hauled their boats out of the sea; would such a day come to this field?

Three or four men stood in front of the old man where he sat smoking, staring into space. “Who’re you?” he asked sharply. “We have come to ask your cooperation,” said a white-haired man politely. For their investigation, they needed to collect some earth and a few stones, they said. “I heard,” Yamada answered. “When the investigation is finished, we’ll take responsibility for returning everything, so … I see there’s water in that jug by the doghouse. We’d like to borrow that if we may—is it rainwater?” asked the white-haired man. “And the potato field…?” asked the other man. “Go ahead,” replied Yamada. “We’re also taking a sample of salt from each household—the salt you use for cooking, so if you wouldn’t mind . . .” added the white-haired man. Yamada got up and got the salt shaker from the kitchen. “You gonna take the whole thing?” he asked as he handed it over. “I believe that will give us a more accurate result,” said the other man.

Taking the salt shaker, two or three potatoes Yamada dug up for them, and samples of earth from various parts of the field, the two men left.

Back at the house, the phone was ringing.

The pool of sunlight outside the barn was growing warmer. The young man holding the sweet potato, pressing it with his thumbs, gazed at the man in the camel hair shirt sitting in the wicker chair. Their eyes met, although they were too far away to see each other clearly. The tall, lean, man who might have been a reporter acknowledged the older man with a slight nod. During the month since the accident, scores of people had come one after the other, asking the same questions. The bevy of tents had disappeared a month before; Yamada had had his fill of questions. Fiddling with the unlit kiseru, he closed his eyes. As the light hit his eyelids, the color of blood rose in his mind. Through the red, he watched the young man draw closer.

“Good morning,” he said as he walked into the yard, holding out a calling card embossed with the name of his newspaper.

“I read your paper.” Yamada spoke at last. He was proud of subscribing to a newspaper most of the village shied away from, saying it was for the “elite.”

“Guess you want to hear about that morning. Well, I was sitting right here,” he began, slapping the arm of his chair.

“Did you notice anything unusual, a loud noise, for instance, or a strange odor? Did you see smoke rising?”

“White smoke drifting up from the box, like Urashima Taro you mean? Nope, nothing like that,” Yamada replied. As usual, there was no emotion in his voice. “But Shiro howled,” he added. Behind his eyelids, Shiro’s fur was a deep red.

“Is that the dog that was barking just now?”

“That’s right. He ran away from you, into the house. He doesn’t like people much since then.”

“Yamada Shiro howled, did he? Do you think he heard something, or felt some vibration you didn’t catch?”

“Must have. But asking about it now won’t get you a news story, will it? A whole crowd came from the TV stations, and there was lots of stuff in your paper, too. Past noon that day they swooped down on us like a hoard of locusts—that road you came down had so many vans and tents on it you couldn’t get near it. At night it was brighter around here than Tokyo nights I’ve seen on TV.”

“Oh?” replied the reporter, turning around to look at the road.

“They sure were quick, those Peace something-or-other folks; a bunch of foreigners came the morning after, Peace something they called themselves, pitched a tent over there, but the Village Headman, he was really something, said that very afternoon he was so worried about us, he took it on himself to tell everybody to evacuate. My son was away three days, getting a health check.”

“And what about you?” the reporter asked, to which Yamada retorted, “Tell a farmer to leave his field for three days? Must be crazy.”

“But I think you should be checked, too.”

“What good would that do? Are they going to guarantee our future? They say they’ll pay everyone 30,000 yen6, but how long can you live on that?

“Guess it was the morning after my son left, got a call from the Public Health Office—how was I feeling, they wanted to know, was I dizzy, or nauseous, asked a lot of questions like that.”

“And what did you answer?”

“Told ‘em I was just fine,” answered Yamada with a yawn.

Two or three days after the accident, it was announced that no radiation had been detected in the village well water, the earth or vegetables grown in it, domestic animals, milk, etc. The collected samples had been examined by category, and the result of the analysis had shown “no artificial radioactive nuclides.” From about thirty samples of topsoil, however, “artificial radioactive nuclides” had been detected. There were assurances that the amount was “much lower” than the radiation human beings would be exposed to from the natural world.

Though he was relieved to hear this report, Yamada had no idea where—from whose fields—those thirty samples of topsoil had been taken. He didn’t want to know, either.

“What did they take to examine?” the young reporter asked, bringing his face up close to Yamada’s. Pushing him away, the old man listed the things that the white-haired official had taken with him, suddenly remembering, “I’ve got to get that water jug back, and the salt from the kitchen—they took some of everyone’s, at least from the houses around here, near the plant.”

“Salt? That’s the first I’ve heard of salt being examined. But after all, it’s something everyone uses—maybe they wanted to measure the average radioactivity level of sodium chloride. Gold—yes, the glittery kind—is often collected, because it’s apparently one of the most sensitive substances to radiation.”

Yamada hooted with laughter. “Gold? The only gold we’ve got is the chain my son wears around his neck, and the gold caps on my molars; if they’d asked I would’ve opened my mouth and let them test away.”

“You’ve got lots of potatoes lying around. They look good, but they’ve gone soft inside. Weren’t you able to sell them?”

“Naw, I dug them up before the accident,” Yamada lied. It broke his heart to remember that harvest day.

It was about a week after the accident when Yamada finally harvested the potatoes. He dug them up with his son, who’d come back from his health check. He didn’t know whether his own field had been affected by “artificial radioactive nuclides,” but either way, he couldn’t leave potatoes ready to be harvested in the ground. Even if he had to throw them away in the end, they’d spent months in the dark earth, waiting to come out, and he had to do right by them. “I can eat them, anyway,” he’d said to his son. “You do as you see fit, Dad, they’re your potatoes,” his son had replied gently.

A mere coincidence—bad timing—Yamada and his potatoes having been caught up in this disaster just as they were nearing the end, yet it was also a great misfortune. He’d stored about half the unlucky potatoes in a hole he’d dug beneath the house. In time they would return to the earth.

“Some government officials ate potatoes from around here on TV, to show they were safe. Didn’t their performance do you any good?”

“Our potatoes are the best, those bigwigs don’t know nothing. A man from the next village over’s in a bad way, could die any time, they say, poor guy,” Yamada said.

Shiro started barking. Starting at the sound, Yamada shook his head to clear the mist away. The shadow cast by the wall receded to the road, letting light pour over the upturned earth. The young reporter was walking through the light. Gazing at the lean, retreating figure, Yamada tilted his head, wondering if it was all a dream.

“Someone laughed out loud just now, didn’t they Shiro?” Yamada asked the dog. “Next year let’s plant some of them sweet purple sprouts from down south.”

It might be his last potato crop. “Why not give it one more try?” he said, gazing across his field where the frost had melted, and white steam rose from the earth.

Related articles

- Hayashi Kyoko, translated and with an introduction by Margaret Mitsutani and an afterword by Eiko Otake, To Rui Once Again

- Hayashi Kyoko, translated by Kyoko Selden, Masks of Whatchamacallit: a Nagasaki Tale

- Kyoko Selden, Atomic Bomb Poems

- Yuki Tanaka, Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro – Confronting Images of Atomic Bomb Survivors

Notes

According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock, which had stayed set at three minutes before midnight for the last two years, has now moved up to two minutes, 30 seconds. See here.

A kiseru is a long, slender wooden pipe with a metal mouthpiece at one end and a small metal bowl for tobacco at the other.

Urashima Tarō is the protagonist of a Japanese folk tale, a fisherman who is taken to Ryūgūjō (the Dragon Palace) by a grateful turtle whose life he saved. After spending what he thinks is three days there, he returns to his village to discover that 300 years have passed.