Abstract

This paper focuses on civic activities to conserve underground sites that reveal the dark heritage of wartime forced labor in Japan. At times collaborating and at other times competing with others, various local groups seek to bring these shameful heritages to the center of the Japanese memory-scape. In doing so, these movements challenge Japan’s homogenizing national war memories and carve out a democratic public sphere to renegotiate understanding of the war heritage.

Keywords: dark heritage, heritage of resentment, heritage of shame, heritage preservation, forced labor, resident Korean

Introduction

Resentment, writes Jean Améry, a victim and survivor of Nazi persecution, is an absurd sense for it “desires two impossible things: regression into the past and nullification of what happened.”1 Yet, the absurd sense of resentment can play a moral function in that it defies “natural” time-sense. Améry continues:

Natural consciousness of time actually is rooted in the physiological process of wound-healing and became part of the social conception of reality. But precisely for this reason it is not only extramoral, but also antimoral in character. Man has the right and the privilege to declare himself to be in disagreement with every natural occurrence, including the biological healing that time brings about. What happened, happened. This sentence is just as true as it is hostile to morals and intellect. The moral power to resist contains the protest, the revolt against reality, which is rational only as long as it is moral.2

Although Améry’s point about resentful memories of the past was based on the European Jewish experience of Nazi crimes, the “retrospective grudge” could be shared by Koreans who experienced wartime injustice under Imperial Japan. Marginalized in postwar reconstruction and development, Koreans in Japan, some of whom are the decendents of colonial and wartime migrant laborers, have encapsulated their resentments in memories of the darkness of underground tunnels and shelters built at the end of World War II.

When total war finally reached the Japanese home islands in the form of massive air strikes in spring 1945, the nation had already begun to build countless underground barracks, trenches, bunkers, shelters, and tunnels to house military headquarters, national institutions and facilities, industrial plants, ammunition, equipment, and machines, as well as to protect the imperial family. Known as “underground warehouses” (chika sōko), The Imperial Army ordered the construction of “underground warehouses” (chika sōko) in Matsushiro (Nagano Prefecture), Asakawa (Tokyo), Rakuten (Aichi Prefecture), Takatsuki (Osaka), and Yamae (Fukuoka Prefecture), to name a few places. The Imperial Navy set out to build underground tunnels in Hiyoshi (Kanazawa Prefecture) about a week after the fall of Saipan in July 1944. When the wartime Diet passed the “Urgent Dispersal of Plants Act” in February 1945 in an attempt to continuously produce munitions in the face of US air raids, the result was an “underground factory boom.”3 A reported 100 underground aircraft plants alone were built throughout the Japanese archipelago from late 1944 to the end of the war.4 The scale of these underground projects was so extensive that the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS), established by the Secretary of War in 1944, conducted a “special study” of underground manufacturing projects. According to a USSBS report, “Because the dispersal of aircraft and engine manufacturing plants to underground locations proved to be far more extensive than had been suspected, a special study of underground plants was undertaken by the Aircraft Division.”5

Although the exact number of laborers mobilized for the construction of underground facilities is unknown and the nature of their labor is still fiercely debated, numerous records, documents, testimonies, and stories make clear that the substantial portion of mobilized laborers were Koreans deported from the peninsula under increasing coercion and were subjected to harsh conditions.6 It is believed that some 700,000 Koreans were recruited or dispatched to Japan between 1939 and 1945. Many of them perished without a trace, while some made their way home after Japan’s defeat, and others remained in Japan after the war and became resident Koreans in Japan (zainichi).7

This paper examines the operational forces and the social conditions in which the physical legacy of forced labor is transformed into dark heritage in contemporary Japan. The term dark heritage is used to convey two metaphorical meanings. On the one hand, the term refers to the “heritage of shame” (fu no bunkazai), containing the memories of modern Japan’s imperial wars of aggression and accompanying wartime atrocities, from which few Japanese draw pride and most prefer to leave in oblivion.8 On the other hand, it refers to the “heritage of resentment” from which the victims of Japanese wartime labor regiment confront painful past as well as pursue present justice. In the meantime, the dark heritage also conveys a literal meaning since these underground sites were literally dark. For this purpose, I will first introduce the Japanese grassroots movement to conserve war-related sites as the heritage of shame by centering on the activities of the Japanese Network to Protect War-Related Sites. Second, I will examine the civic activities to conserve the heritage of resentments initiated by ethnic Koreans in Japan and responded to by conscientious Japanese citizens. In so doing, I bring into focus shameful and the resentful memories that challenge the tendentious war memories of victimhood in Japanese society.9 In the meantime, I also probe the tension between the shameful and the resentful heritage to argue that the places designed to facilitate plural remembrance is pivotal in envisaging historical reconciliation and negotiating historical injustices both at subnational and international levels.

Conserving the Heritage of Shame: The Matsushiro Case*

The Japanese Network to Protect War-Related Sites (hereafter, the Network) was formed in 1997. Articulated in numerous publications of the Network and by the involved activists and scholars, war-related sites refer to “the heritage of shame” and include “the built structures and materials that were produced to execute Japan’s aggressive wars.” The Network limits war-related sites to the buildings, structures, and materials that were produced “from the Meiji period when the modern military system was created to the early Shōwa period when the Asia-Pacific War was concluded.” These built structures and sites are directly related to “the aggressive wars of Japan in terms of perpetration, suffering, collaboration, or resistance.” Since most of the wars Japan waged in modern times were fought abroad, these war-related sites exist both in and outside of Japan. As an example of work outside of Japan, in order to investigate the existence and condition of war-related sites in China, the Network has carried out collaborative investigation with Chinese scholars and activists since 1993.10

The Network strives to differentiate its position from that of other efforts to make war-related sites memorials to the war dead by glorifying their sacrifice for the state. The glorification of war dead and war, the Network claims, is often carried out at the expense of remembering civilian sufferings and losses caused by the Japanese state, let alone the suffering caused to other Asian people. For example, Kikuchi Minoru, a working committee member of the Network, pointed out in his report at the most recent symposium in 2013 that “most cases of excavating skeletal remains from underground sites in Okinawa have been carried out for the sake of memorialization and hardly for the purpose of returning those remains to the family members of the deceased.” It is necessary to redefine the purpose of retrieving human remains while simultaneously “investigating the historical reasons for the existence of underground sites, and the conditions of remains at the time of excavation.” For this purpose, he calls for continuous interdisciplinary collaboration among historians, archeologists, anthropologists, and other specialists of conservation.11

In fact the Network is an association of various civil and scholarly organizations including the National Association of Cultural Property Preservation, the Association of History Educators, the Research Association of Archaeology of War-Related Sites, the Okinawa Peace Network, and the Matsushiro Underground Imperial General Headquarters Complex Preservation Association, among others. In addition to these participating members, a related guidebook for nationwide war-related sites lists 45 local organizations involved in similar conservation movements.12

Since the practices of excavation and conservation of war-related sites are methodologically tied to the field of archeology, some professionals in the field were active in the Network from its inception. Actually the need for the “archeology of war-related sites” was pointed out by a scholar named Tōma Shiichi in 1984. Based in Okinawa, the site of the only battleground on Japanese soil during WWII, Tōma was deeply troubled by the social practices of collecting human remains without any reflection on the Battle of Okinawa itself in which more civilians than soldiers perished. In an article entitled “An Invitation to the Archeology of War-Related Sites,” Tōma called for archeological research and investigation of both natural and artificial caves scattered on the island to “re-experience” the Battle of Okinawa.13 This archaeology of war-related sites became an official sub-discipline of the Japanese Archaeological Association at the Association’s Okinawa symposium in 1997.14

The Network’s first national symposium took place in Matsushiro, Nagano Prefecture in 1997. Matsushiro is both symbolically and practically an important site in the making of the dark heritage in general and of the Network in particular. Matsushiro developed as a castle town of the Sanada clan and is known for its scenery; it is sometimes referred to as “little Kyoto of the Shinshū region.” The place, however, also contains evidence of a not-so-well-known dark history, having hosted a gigantic complex of underground shelters and tunnels under the three mountains of Maizuru, Zōzan, and Minakami. These underground facilities were constructed during the last ten months of WWII. They were designed to relocate the Imperial General Headquarters as well as the imperial family and other state organs from Tokyo, including ministries and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK), in preparation for the impending “Final Battle” expected to take place on Japan’s main islands. The total length of the three main tunnels for underground shelters was about ten kilometers. The Nishimatsu Construction Company and the Kajima Construction Company carried out the construction using primarily Korean laborers. An estimated 6,000 to 8,000 Koreans were mobilized for the construction; among them, by some estimates as many as 1,000 are estimated to have died from malnutrition, accident, and execution.15

Sensitive to this history, local citizens began conservation movements through three organizations. The first is the Matsushiro Underground Imperial General Headquarters Complex Preservation Association (hereafter Matsushiro Preservation Association) organized in 1986. The civil organization was partly inspired by a group of local high school students who petitioned the local government to conserve the underground shelter by making it a cultural property. Investigation of ethnic discrimination toward Koreans had earlier been undertaken by local students, scholars and writers. For example, students of Shinshū University, inspired by Pak Kyong-sik’s The Record of Koreans Forcefully Taken (Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō no kiroku) (1965), organized a Korean Cultural Study Group to investigate the forced Korean labor used to build the underground complex. Meanwhile, Wada Noboru, a children’s book writer from Nagano, published a nonfiction book entitled The Fortress of Sadness based on research on Korean forced laborers.16 Awakened by these activities, concerned citizens organized the Matsushiro Preservation Association to lead the movement for conserving and opening the underground complex to the general public. From the beginning, many activists in this organization were middle-school and high-school teachers.17 For example, the first president of the Matsushiro Preservation Association, Aoki Takaju, was a high-school social studies teacher who later became a professor at the College of Nagano Prefecture.18

The second organization is the Matsushiro Imperial General Headquarters Memorial Stone Protection Association (hereafter Memorial Stone Protection Association), formed in 1995 around the movement to erect a memorial stone for Korean victims of the construction of the underground complex.19 The activists involved in the movement were particularly inspired by an animated film called The Cross of the Kim Brothers. The animation was based on a nonfiction work of Wada Noboru published under the same title in 1983. While promoting the nationwide showing of the film, the concerned activists researched the identity, number, and conditions of forced Korean laborers and began a movement to erect a memorial to remember them in 1991. By 1995, the movement successfully raised two million yen and erected the memorial near the entrance of an underground shelter under Mt. Zōzan.

A central figure of the movement to remember Korean victims is Harayama Shigeo. By the 1990s, Harayama was deeply involved with the local movement to conserve the underground complex. Also working as a teacher, Harayama once headed the Nagano Prefecture Teacher’s Union Executive Committee and was the vice-president of the Matsushiro Preservation Association. During the war, as a “patriotic youth (gunkoku shōnen),” Harayama volunteered for the navy at age 16 in 1944 and now identifies himself as a “perpetrator (kagaisha).” To him, the movement to remember Korean victims was a way to “repent (tsumi horoboshi).”20 While fund-raising for the memorial stone, Harayama investigated and published the number of Korean forced laborers who were both mobilized and died, their identities, and their harsh work conditions. Assisted by the Nagano branches of Korean Japanese associations, he was able to track down and interview Korean survivors of forced labor or members of the bereaved families, living both in Japan and Korea.21 Despite his extensive efforts, the names of only three Korean laborers and one Japanese who died at the site are known to this day.

The third group of Nagano local citizens is derived from the movement to build Another History Museum, Matsushiro. The incident that triggered the movement occurred in 1991 when the public learned that an old building near the underground complex that was used as a “comfort women station” during wartime was to be destroyed.22 To stop this, an Executive Committee to Preserve the Matsushiro Korean “Comfort Women Station” was formed and began raising funds to preserve the building. The Executive Committee managed to secure land near the entrance of the Zōzan underground shelter in 1995 and changed its name to Another History Museum in 1996.

It was also around this time that the international society at last came became aware of Japan’s wartime crimes against women and the existence of “military comfort women.” Several aging “comfort women,” starting with Kim Hak Soon, came forward in 1991 to tell their horrible experiences, spurring transnational movements to compensate these aging victims and to press the Japanese government for official acknowledgement, apology and reparations for its wartime atrocities.

Another History Museum was profoundly influenced by this transnational development and is committed to revealing, remembering, and transferring “history from the viewpoint of the ruled and victimized” by conserving not only the underground complex but also the “comfort women station” in Nagano.23 In 1998, the group opened a small history museum on the secured land. The museum is designed “to easily learn and to collect information” about the history of the Matsushiro underground complex and the issues of war and gender. The museum exhibits tools and photographs to document the harsh conditions of forced labor. It is also intended “to be used for meetings between Japan and South Korea, Japan and North Korea, and local and national people.”24

The members of Another History Museum are inspired not only by the “comfort women” but also by a woman of local origin named Yamane Masako.25 Born in 1939, Yamane Masako was a daughter of a Korean man who worked on the underground complex and a Japanese woman. The family survived the war, and all but Masako were sent to North Korea in 1960. Yamane decided to stay in Japan at the last minute. She moved to Tokyo and tried to wipe out all evidence of her past, including her ethnic origin. It was her encounter with Wada Noboru’s work, The Cross of the Kim Brothers, that led Yamane to become a devoted activist, digging out and publicizing the stories of Korean forced laborers and “comfort women” in Matsushiro to the end of her life in 1993.26

All three civic groups working to conserve the Matsushiro underground complex belong to the progressive camp in Japanese society in that they all share the belief that the heritage of shame must be conserved and that the legacy of suffering needs to be remembered. To achieve this goal, all three groups are committed to the education, research, and publication of the history of the underground complex. For example, the Matsushiro Preservation Association makes great efforts to train volunteers to guide visitors to the area. Thanks to these active local civic movements, the underground complex has gained not only national but also international attention, with more than 100,000 people visiting every year during the last decade.27 To accommodate the growing number of visitors, the Matsushiro Preservation Association holds regular “classes to train guides for Matsushiro.” The vice-president of the Matsushiro Preservation Association, Ato Mitsumasa, proudly pointed out that the percentage of guides provided by the Matsushiro Preservation Association to the total number of visitors increased from 14.7% in 2001 to 24.7% in 2010.28 Members of Another History Museum also emphasised holding regular meetings to study and research local history. The number of visitors to Another History Museum reached 8,000 per year for the last three years.29

All the activists, regardless of their associations, firmly believe in the power of material places and things to transfer past experiences to new generations because places and things can recreate “the past as it happened” in the here and now. The assumption is that “history told by things (mono ga kataru rekishi)” is truthful and objective; by implication, material objects are particularly suitable for telling and revealing the history of the ruled and victimized.30 It is also believed that “learning by experience (taikensuru),” such as actually going into the underground complex or lifting a tool used by forced laborers, leads the visitor “to think with one’s own head (jibun no atamade kangaeru).”31 In other words, unless one learns by experience the past cannot be clearly known (“pinto konai”).32 Putting its trust in the power of physical place, the Matsushiro Preservation Association is especially active in pressing the local government to designate the underground complex as a historic site. The activists are particularly concerned that the underground complex is administered by the sightseeing section of the Nagano city government and, therefore, about the possibility of its being utilized as a mere tool to promote tourism.33

The physical inheritance of the Matsushiro underground complex has provided a material ground on which local people encounter the shameful past of discriminating against the different other; and through this they can transfer shared knowledge of the past that included the memories of suffering.34 As shown in the existence of three layers of the Matsushiro conservation movement, there is subtle difference in the tenor of activities, especially, in Another History Museum. Marked by the resentful voice of Korean victims and their descendants, the presence of permanent resident Koreans, often referred to as zainichi, was discernable. Calling Matsushiro “almost like Japan’s Auschwitz,” Yamane Masako, the central figure in Another History Museum, criticized the signboard erected in front of the entrance of Zōzan tunnels by Nagano City that made no mention of Korean laborers.35 She said, “I do this work, because I am trying to discover why those Koreans were brought to Matsushiro by force and what happened to them.”36 It was this commitment to bringing the resentful memories to light that some zainichi and like-minded Japanese are singlehandedly working to conserve underground sites with a goal of uncovering the reality of wartime forced labor in Japan.

Making the Heritage of Resentment: The Kansai case

Wartime forced labor has been the focus of the National Conference on Koreans and Chinese Forced Laborers (Chōsenjin/Chūgokujin kyōsei renkō, kyōsei rōdō wo kangaeru zenkoku kōryū shūkai, hereafter the Conference on Forced Laborers) long before the Japanese Network called for conservation of war-related sites. The first meeting of the Conference on Forced Laborers took place in Nagoya on August 25, 1990, followed by field trips to two underground munitions plants in the nearby areas. A reported 250 people gathered from 31 different organizations from all over Japan.37 Takeuchi Yasuto, an activist from Shizuoka, recalled that “the first conference was a heated one with the participation of the first generation zainichi.”38 Since the first meeting, the Conference on Forced Laborers held annual meetings in different places and made field trips to remains throughout the underground empire.

The shared resentment toward past injustice among resident Koreans and Japanese citizens was expressed in the opening announcement of the first Conference on Forced Laborers:

For forty-five years since the end of the war and since the liberation for Koreans, the Japanese government and we Japanese have continuously covered up and forgotten the history of aggression. In particular the fact of forced migration and labor has hardly been examined so far. Over a million Koreans and Chinese forced laborers were subjected to the harshest labor and many perished. These things happened not far from where we live. Perhaps that is why the fact has been covered up or distorted. Unless we bring the fact to light and fix it, Japanese co-existence with Koreans and Chinese and the internationalization of Japan is impossible.39

It was clear from the first meeting of the Conference on Forced Laborers that participants expressed interest in the conditions and conservation needs of underground facilities in different local areas. There were reports regarding the underground tunnels in Takatsuki and Hachiōji, the underground munitions plant in Seto and Kurashiki, and the underground headquarters in Matsushiro. The participants made field trips to two underground munitions plants, one in Kukuri and the other in Mizunari, in Gifu Prefecture which by the end of the war hosted 13 dispersed underground munitions plants.40

The Kukuri plant is located in the hills 32 kilometers northeast of Nagoya. The plant was designed to produce the Mitsubishi No. 4 Engine Works. According to the USSBS report, “[A]n elaborate network of 38 tunnels totaling 23,000 feet in length was excavated in a ridge of sedimentary rock. The tunnels measured 16 feet wide and 11.5 feet high… This plant was to manufacture engines but no actual production was achieved.”41 Construction of the plant started in late December, 1944, and about 2,000 workers were mobilized. Reportedly 90% of the workers were Koreans.42

Kim Bong-soo, a second generation zainichi recalled that the Kukuri underground plant was “a gigantic tunnel that could rival the Matsushiro Imperial General Headquarters.” Kim called for the conservation of the underground site of Kukuri:

A half century has passed since the end of the Pacific-War. In other words, a half of century has passed since the demobilization. The word “demobilization,” for the remaining few first generation Korean permanent residents (zainichi Chōsenjin), still conveys lively and vivid memories…..

The Japanese authorities are quibbling about the remaining few documents and are not confronting the reparation requests emanating from various places in Asia. Despite treaties and agreements, the Japanese government is not confronting the suffering Japan inflicted and the harmed lives of Asian people.

In this situation, we photographed the reality of past Japanese aggression that is materialized in the everyday scenery around us.43

In this way, the participants in the Conference on Forced Laborers sought to retrieve wartime memories of forced labor and attach them to places so as to re-frame the national narratives that underestimated the duration, extent, significance, and legacy of forced labor in wartime and postwar Japan. In the ensuing annual meetings, the Conference on Forced Laborers continued to investigate the histories and conditions of various underground facilities, to exchange information on conservation strategies and activities, and to discuss the significance and implications of conservation for remembering suffering caused. In all these meetings, one individual made repeated appearances.

From the first meeting, Pak Kyong-sik regularly participated in annual meetings of the Conference on Forced Laborers. Pak, who published a seminal work on the Korean forced labor in Japanese in 1965, made the closing speech at the first Conference on Forced Laborers stating: “As for Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese, the problem of forced migration and forced labor must be understood in relation with the problem of Japan’s colonial rule over Korea and its aggressive war against Asia.”44 In his view, the problems of colonial rule and forced migration were intertwined with the “perception of history,” i.e., the questions of how to think about modern Japanese history, modern Korean history, and modern Asian history. Japanese perceptions of history until now have been seriously distorted, Pak pointed out. By correcting this distortion, he continued, “one can eradicate the narrow Japanese perspective of themselves, the perspective of a homogeneous nation, so as to achieve true international relations;” the “ultimate goal must be changing Japanese society with our movement.”45

Born in 1922, Pak migrated to Japan at the age of six. Growing up in Japan, he taught at Chosun middle and high schools and later Chosun University in Tokyo.46 After the war, he pioneered investigation into Korean forced labor and published a book entitled The Record of Koreans Forcefully Taken in May 1965, a month ahead of the signing of the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea.47 The treaty was supposed to “normalize” relations between the two. Yet, the agreement was accompanied by a Japanese economic assistance package of $800 million in grants and loans to the Park Chung Hee government in the name of “congratulating” Korea on its independence, while sidestepping colonial and wartime issues, including the unpaid wages of forced labor.48 Pointing out that the new and equal relationship between Japan and Korea could not be established unless colonial and war responsibilities were addressed, Pak further observed that the lack of critical self-reflection by the Japanese about their violent colonization and imperialist rule of the Korean people was the root of the ongoing problem of Korean minorities in Japan. He criticized the fact that “even progressive Japanese, who call for international solidarity, fail to pay sincere attention to Korean [problems].”49

Pak began his research on Korean forced labor after first investigating Chinese forced labor issues. While researching Chinese forced labor, he noted a lack of evidence, information, and interest in Korean forced labor issues in Japanese society. His book The Record of Koreans Forcefully Taken was his way of dealing with the issue. The book struck a responsive chord among concerned Japanese citizens and led to the formation of the Korean Forced Labor Truth Investigation Committee in 1972, which carried out investigations in Okinawa, Kyushu, Tohoku, and Hokkaido and published a report in 1975. Based on some fact findings and continued investigation activities, scholars and activists on forced labor problems held the first meeting of the Conference on Forced Laborers in 1990.50

As already pointed out by a Japanese participant, the Conference on Forced Labor was marked by the presence of resident Koreans, the largest ethnic minority in Japan. Yet, the commitments and activities of concerned Japanese citizens were no less present. Many of the Japanese who responded to the calls of ethnic Koreans were moved by the work of Pak. Hida Yūichi, the director of the Kobe Student Youth Center and a central member of the Conference of Forced Labor from its formation, recalled the tremendous impact of the book on him, which led to the forging of a lasting personal as well as professional relationship with Pak.51 Sakamoto Yūichi, an economic historian and activist, recalled being in tears when he first read the book as a high-school student.52 Sakamoto has also been an active member of Takatsuki “Tachisō” War-Related Site Conservation Association (Takatsuki “Tachisō” senseki hozon no kai, hereafter Tachisō Conservation Association).

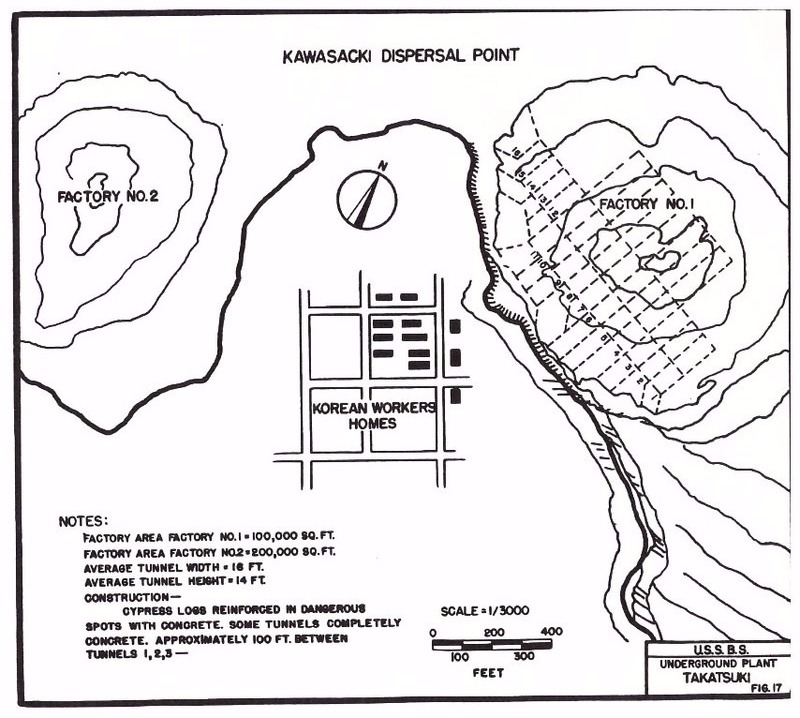

“Tachisō” is the abbreviated name for the “Takatsuki Underground Warehouse (Takatsuki chika sōko).” Located midway between Osaka and Kyoto, the Takatsuki underground facility was one of the warehouses originally intended for the use of the Imperial Army. Its construction began in November 1944. When the Kawasaki Airplane plant in Akashi (Hyogo Prefecture) was hit by the US bombers in January 1945, the usage of the Tachisō tunnels was changed in February to the dispersal plant for the Kawasaki’s Akashi plant to produce the engine for air fighters.53 The total size of the underground facility is still unclear, but the complex contained about 30 or more tunnels spread on about 9,000 square meters under forested hills. According to the USSBS report, “[A] force of 3,500 Koreans living in the valley was engaged in the construction of this plant.”54 The exact number of Koreans is still being debated, and their identities are largely unknown. The nature of the recruitment methods is also still debated.55 Suffice it to say the degree of coercion increased, and working and living conditions of Korean laborers were harsh. Located in the area named Nariai, “the Korean Workers Home” in the map, was often referred to as hamba in Japanese, a temporary barrack for construction workers.

|

Map 1: Tachisō Underground Warehouse by the USSBS in 1947 |

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Underground Production of Japanese Aircraft, p.58

|

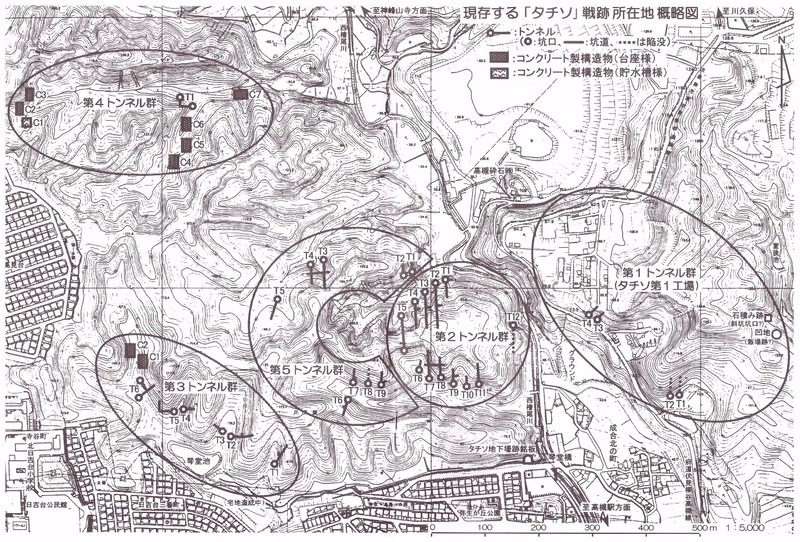

Map 2: Tachisō Underground Warehouse in 2007 |

Takatsuki “Tachiso” senseki hozon no kai, ’Tachiso’ annai panfuretto, pp.8-9

According to Tsukasaki Masayuki, a local historian and a member of the Tachisō Conservation Association, working conditions of Korean laborers were brutal and exploitative, diets were inadequate and poor, and medical care was virtually nonexistent.56 This assessment was based on internal reports by the Takatsuki Police Chief submitted to the Osaka Police Director or the Special Higher Police (Tokubetsu kōtō keisatsu, often shortened to Tokkō), a police force specializing in investigation and control of political and ideological groups and activities. The reports, which were discovered by Tsukasaki in the archive of the National Institute for Defense Studies, involved 83 cases with 474 pages, written between April 27 and July 1, 1945.57 One report, marked stamped “June 2, 1945”, was on Korean laborers. According to the report, the Korean laborers worked in “two-shifts of 11 hours each” (for “outside work”; in case of “inside work,” “four-shifts”). As of June 1945, two Koreans had died and 151 had been injured. At the time, a virulent contagious skin disease, caused by a mite (kaisen), occurred in the area, but no medical care was provided.58

Some Korean survivors stayed in the same hamba-site in Nariai after the war. One of the direct triggers for Nariai Koreans to raise their voices was the lawsuit brought by Japanese landowners of the hamba-site against 47 Korean households, accusing the Koreans of being “illegal occupiers” in June 1964.59 The Ministry of Army “leased” the Nariai area from the Japanese landowners for the Tachisō construction in late 1944. After the defeat, however, the leaseholder disappeared when the new constitution disbanded the military and the postwar state did not assume legal responsibility of the prewar state. As a result, the legal dispute over land usage was left between Japanese owners and zainichi Koreans. Some Nariai Koreans reached out to Japanese citizens by recalling that the underground tunnels were the historical reason for their presence in the area and the material basis for their call for fair treatment.

Some local concerned Japanese responded to these calls. They organized the Takatsuki Citizens Group to Conserve War Records (Sensō no kiroku wo nokosu Takatsuki shimin no kai, hereafter Takatsuki Citizens Group) in 1982.60 Activities of the Takatsuki Citizens Group included: 1) collecting written and oral materials regarding the Tachisō; 2) investigating the history and conditions of the remains of Tachisō; and 3) making field trips to nearby underground facilities in the Kansai region to compare them with the Tachisō.61 These activities are, in the words of Sakamoto Yūichi, “essentially the peace movement in a general sense.” Yet, the main feature lies in the promotion of peace via undeniable facts embedded in the physical record of wartime experiences. There were two types of histories they intended to “dig out.” One was “the local history that bulged out from war records;” the other was “the history that included the record of inflicting suffering (kagai) on other ethnic people.”62 In this way, some Japanese responded to the Nariai zainichi’s call by attaching the local history to the remains of underground site.

Sakamoto, who participated in the group from its inception, pointed out problems as well as achievements in their activities. Membership was limited to school teachers who had been involved in peace education and few Nariai residents participated in the local activities. Within the group, there was no consensus regarding the notion of “inflicting suffering.” Internal conflict, Sakamoto continued, was in part caused by the “existence of the view that zainichi Korean education was a branch of “liberation education,” i.e., the view that “Japanese = perpetrator = discriminator.” Takatsuki’s radical education perspective, however, was problematic in terms of 1) neglecting the suffering brought to Koreans by colonization and the Asia-Pacific War; 2) excluding the history of Korean resistance against colonization and aggression; and 3) ignoring the history of joint effort by Korean resistance and Japanese antiwar activists.63

Perhaps the essence of discord among members in dealing with Nariai and underground sites is the tension between “shameful” and “resentful” memories. Disturbed by the history of aggressive war, some Japanese preferred that shameful memories be kept silent. Resentful of sufferings experienced, some zainichi Koreans were determined to recall the underground tunnels. The materiality of underground tunnels, however, made some Japanese envisage “a vibrant ‘agonistic’ public sphere of contestation,” to borrow Chantal Mouffe’s words.64 The experience of Yakumoji Sayoko is a case in point. Yakumoji, a stenographer and an active member of the Tachisō Conservation Association, became interested in the grassroots movement around the time when the history textbook controversy occurred in 1982. As the mother of a school-age child, she was interested in problems of Japanese history education and established contacts with the zainichi Koreans. Being in the Kansai region, she was sensitive about issues regarding discrimination against minorities especially zainichi and burakumin. When she “discovered” the Tachisō, she was profoundly surprised (bikkurishita) to learn of the evidence of Japanese wartime aggression so close to her everyday life. The locality of dark underground sites provided the physical ground on which the empathy toward sufferings of others became possible.65 For Yakumoji, the existence of the physical site played a pivotal role in resolving the tension between shameful and resentful memories at the personal level and in becoming politically active at the societal level. Seen from this angle, the conservation movement became a potent political channel for dissenting voices of ethnic Koreans in Japan and their call for redrawing “the we/they distinction in a way which is compatible with the recognition of the pluralism.”66 Sensitized by the materiality of underground sites, sympathetic Japanese citizens responded to the call in the form of grassroots conservation movements.

The conservation movement flourished in the mid-1990s and gained nationwide attention and support for their cause. The Tachisō Conservation Association was successful in publicizing the very existence of the Tachisō. Tsukasaki recollected that he guided as many as many as 70 groups a year from all over Japan in the mid-1990s.67 Another major achievement of the association was the erection of a stone-marker near the Tachisō site in 1996. With the inscription “3,500 Koreans were forcibly mobilized,” the stone-plate explained the history of the underground tunnels (Photo 1). However, he lamented, the conservation movement subsequently lost momentum. Reasons he listed are: 1) a failure to educate and mobilize younger activists in the region; 2) the general weakening of labor and progressive movements in Japanese society; and 3) the disintegration of zainichi Korean organizations.68 Moreover, the tunnels themselves were crumbling and disappearing one by one with the passage of time. Many tunnel entrances were already obliterated by cave-ins. To continue its battle against both social and natural oblivion, the Tachisō Conservation Association is preparing to publish a photo record of the remains of wartime underground facilities.

|

Photo 1: The Stone Plate of the Tachisō (Taken by the author on April 15, 2015) |

Photo 2: One of the Remaining Few Tunnel Entrances of the Tachisō (Taken by the author on April 15, 2015) |

Conclusion

The physical remains of the underground empire and the materiality of war-related sites proved crucial in reconfiguring war memories for many in Japanese society. To appropriate Jean Améry’s words, the remains of underground sites are the signposts of passages to regressing on into the past and defying what happened. Determined to preserve the wartime memories of forced labor, zainichi Koreans turned to the physical remains of underground tunnels. They challenged Japan’s mainstream war memories that rendered the Japanese, not the Koreans, the victims of the wartime government and demonstrated the existence of ongoing discrimination against ethnic minorities in Japan. The dissenting voices of zainichi Koreans played a critical role in conserving the memories of Korean suffering in the Kansai region. Sensitized by the local remains of underground sites and conscious of the deeply entrenched discrimination toward minorities, Japanese citizens responded to the zainichi call to bring wartime underground facilities to light and organized grassroots groups in their own localities. Yet, as seen in the Matsushiro and Tachisō cases, subtle discord and tension remains between shameful and resentful heritage making. Although it remains to be seen how conservation movements will continue their struggle against “the immensity and monstrosity of the natural time-sense,”69 the shameful and resentful memories must be externalized in the form of dark heritage so that a space for new forms of power relations and social solidarity can be created.

Notes

Jean Améry, “Resentments,” in At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), p.68

Jūbishi Shunbu and Kikuchi Minoru eds., Siraberu sensō iseki no jiten (Tokyo: Kashiwa shobō, 2002), pp.63-4.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, The Japanese Aircraft Industry (May 1947), pp.38-9, (Accessed 06 October 2013)

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Underground Production of Japanese Aircraft, Report No. XX (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1947), p. 1, (Accessed 15 March 2015)

On the issues of forced labor in wartime Japan, see, Pak Kyong-sik, Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō no kiroku (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1979); Yamada Shōji, Koshō Tadashi, Higuchi Yūichi, Chōsenjin senshi rōdō dōin (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2005); and Tonomura Masaru, Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō (Tokyo: Iwanami shinso, 2012). In English, see, Edward W. Wagner, The Korean Minority in Japan 1904-1950 (New York: Institute of Pacific Relations, 1951); Michael Weiner, “The Mobilization of Koreans during the Second World War,” Stephen S. Large ed., Shōwa Japan: Political, Economic, and Social History of Japan, 1929-1989, Vol. 2, 1941-1952 (London: Routledge, 1998) ; and Paul H. Kratoska, “Labor Mobilization in Japan and the Japanese Empire” in Paul H. Kratoska ed., Asian Labor in the Wartime Japanese Empire: Unknown Histories (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2005).

On the history of Koreans in Japan, see Sonia Ryang, “Introduction: Resident Koreans in Japan,” Sonia Ryang ed., Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin (London: Routledge, 2000), pp.1-12.

For a discussion of the “heritage of shame” see, my “Conserving the Heritage of Shame: War Remembrance and War-Related Sites in Contemporary Japan” (2012) and “Relics of Empire Underground: The Making of Dark Heritage in Contemporary Japan” (2016).

Discussions of mainstream war memories of victimhood include Yoshida Yutaka, Nihonjin no Sensōkan: Sengoshi no naka no henyō (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2005); James J. Orr, Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2001); Franziska Seraphim, War Memory and Social Politics in Japan, 1945-2005 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006); Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter, “Introduction: Re-envisioning Asia, Past and Present,” in Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter eds., Ruptured Histories: War, Memory, and the Post-Cold War in Asia (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007); Philip Seaton, Japan’s Contested War Memories: The ‘Memory Rift’ in Historical Consciousness of World War II (London: Routledge, 2009); Ran Zwigenberg, Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

*This discussion is based on my previous publications, “Conserving the Heritage of Shame: War Remembrance and War-Related Sites in Contemporary Japan” (2012) and “Relics of Empire Underground: The Making of Dark Heritage in Contemporary Japan” (2016)

Obinata Etsuo. “Sensōiseki hozon no igi to kadai,” Sensō sekinin kenkyū, No. 19 (March 1998); Jūbishi Shunbu. “Kichō hōkoku: Sensōiskei hozon undō no tōdatsuden to kadai,” Zenkoku simpojium hōkokushū (Nagano: Sensōiseki hozon zenkoku nettowa^ku, 2001); Sensō iseki hozon zenkoku netto wāku ed., Nihon no sensō iseki. The Network’s position did not go unnoticed and the Japanese scholars of military history had suggested the term “military heritage (gunji isan)” to refer to “the heritage bequeathed by the people engaged in military forces, military preparations, and wars.” For the discussion of “military heritage,” see “Roundtable Meeting on ‘Modern Military Heritage and Historic Sites,” Gunji shigaku, Vol. 48, No. 4 (March 2013), p.22.

Kikuchi Minoru, “Kichō hōkoku: Sensōiskei hozon no genjō to kadai,” Dai 17 kai sensōiseki hozon zenkoku simpojium, Okayama ken Kurashiki daikai (Nagano: Sensōiseki hozon zenkoku nettowāku, 2013), pp.7-8.

Tōma Shiichi, “Senseki kōkogaku no susume,” Nandō kōkogaku dayori, No. 30 (1984). Reprinted in Han-gaku kōkogaku genkyūsha no kai, Sensō to heiw to kōkogaku (1988), pp.79-80.

Jūbishi Shunbu and Kikuchi Minoru eds., Siraberu sensō iseki no jiten (Tokyo, 2002), pp.183-85; Aoki Takajū, Matsushiro Daihonei: Rekishino shōgen (Tokyo: Shin Nihon Shuppansha, 2008); Harayama Shigeo. Shin Tesaguri Matsushiro Daihonei: Keikaku kara shabetsu no konkyo made (Nagano: Nagano krooni, 2009).

Many of them were also members of the Japan Teachers Union. Since its establishment in 1947, the Japan Teachers Union has taken a critical stance against the conservative Ministry of Education on issues involved in education in general and history textbooks in particular.

The current secretary-general of the Matsushiro Preservation Association, Kitahara Takako, was one of his students and was also a teacher. The office of the Matsushiro Preservation Association, Kibō no Ie, is the former house of Professor Aoki. Interview with Kitahara Takako on January 26, 2011.

Harayama Shigeo, Shin Tesaguri Matsushiro Daihonei: Keikaku kara shabetsu no konkyo made (Nagano: Nagano koronī, 2009), pp.233-35.

Harayama, op. cit., pp. 236. As a result of his research, Harayama edited a book of oral testimonies of both Korean and Japanese people involved in the construction of underground shelters. See, Matsushiro daihonei rodōshōgenshu henshū iinkai hen, Ganin no katari: Matsushiro daihonei kōji no rodō shōgen (Nagano: Kyōdo shuppankai, 2001). Harayama also collaborated with Koreans and published a Korean translation of Wada’s The Cross of the Kim Brothers in 2001. He revealed the multilayered structure of forced labor in which Koreans were ‘drafted’ through various routes. See the research report by Harayama Shigeo Matsushiro daihonei kōji no rodō: Sono zenbō to honjitsu wo tomoni kiwameru tameni (Nagano: Kinreisha, 2006).

The “comfort women station” was deconstructed, but the materials were secured by the Another History Museum. It is a goal of the organization to reconstruct the station in the future. Based on an interview with a member of the Another History Museum, who requested anonymity, on January 25, 2011.

“Mōhitotsu no rekishikan, Matsushiro” kensetsu shikkō iinkai, Matsushiro wo aruku: Shōgen to gaido – Matsushiro daihonei to ‘ianfu’ no ie (Chiba: Kensetsu shikkō iinkai Chiba jimukyoku, 2004, Kaisei dai 2 han), pp.40-2.

About Yamane, see Higaki Takashi, “Mokusatsu no chikagō”; Yamane Masako ed., Matsushiro daihonei wo kangaeru I/II (Tokyo: Shinkansha, 1991); and Yamane Masako, “The Emperor’s Retreat,” Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook eds., Japan at War: An Oral History (London: Phoenix Press, 2000), pp. 432-337.

Data provided by the Matsushiro Preservation Association. This was indeed a dramatic increase, compared to the number of visitors per year in the mid-1980s, around 1,500. See, Higaki op. cit., p. 58.

Based on the data provided by the Matsushiro Preservation Association and the interview with Ato Mitsumasa in January 26, 2011.

Kuro, “Henshū kōki: ‘Shiryō saisei’ ni mukete,” Mōhitotsu no rekishikan, Matsushiro nyūsu, Vol. 57 (March 14, 2010). It is also pointed out that “the role of a historic site is to be in charge of truthful understanding of history.” See, Suzuki Jun, “Kindai iseki no tayōsei,” in Suzuki Jun ed. Shiseki de yomu Nihon no rekishi, Vol. 10: Kindai no shiseki (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2010), p. 247.

Interview with Ms. Miyamoto, a staff at the Another History Museum, Matsushiro, on January 25, 2011.

Interview with Shimamura Shinji, a member of the Matsushiro Preservation Association and the Network, on January 26, 2011.

It has been reported that the city is acknowledging the site only “as a facility for sightseeing” but not as a historic site. The logic is as follows: “the underground shelter was not used for the Imperial General Headquarters. The place has never been used for the purpose and ended as a mere plan.” Higaki, “Mokusatsu no chikagō,” p. 45. On the ongoing tension between the city and the activists on how to use the site, see Ibid., pp.58-9.

As of August 2016, the Matsushiro Preservation Association is still struggling to make the underground complex a cultural property recognized by the local government.

Asahi shimbun, 26 August 1990. For more detail, see Zenkoku kōryū shūkai jikkō iinkai ed., Dai ichi kai Chōsenjin/Chūgokujin kyōsei renkō, kyōsei rōdō wo kangaeru zenkoku kōryū shūkai hōkokushū (Nagoya, 1990), p. 61.

Takeuchi Yasuto, “Shizuoka-hyun esō jungae deon han’in kangje nodong jinsan kyumyung undong,”Kim Kwang-yul trans. and ed. Ilbon simin yoksa bansung undong: Pyonghwa-jokin Han-Il kwangae-rul uhan jeun (Seoul: Sunin, 2013), p.188

Pittamu no kai (Motohashi Masao), “Kaikai no aisatsu,” Zenkoku kōryū shūkai jikkō iinkai ed., Dai ichi kai, pp.4-5. The name Pittamu no kai is a combination of Korean and Japanese. “Pittamu” is Korean, literally meaning “blood and sweat,” written either in Korean or katakana.

Zenkoku kōryū shūkai jikkō iinkai ed., Dai ichi kai, p. 45. The other was in Mizunami where the Kawasaki Aircraft Co. dispersed to produce parts. Construction of the underground plant started in November 1944 and continued to the end of the war. Katō Takeshi (?), a former high school teacher who investigated the tunnels, explained that 330 Chinese POW’s were forced to work. The participants also visited the top of the hill, where the monument that pledged no more war against China was erected. See, Ibid., p.48.

Shōgensuru fūkei kankō iinkai ed., Shashinshū Shōgensuru fūkei: Nagoya hatsu/Chōsenjin Chūkokujin kyōsei renkō no kiroku (Nagoya: Fūbaisha, 1991), pp. 18-25.

The university was established by Chongryun with the support of North Korea in 1957. The main medium of instruction is Korean.

Takeuchi Yasuto, “Pak Kyong-sik, Chōsenjin kyōsei renkō no kiroku,” Nihonshi kenkyū, No. 615 (November 2013), p. 68.

There were also diverging interpretations on the legality of old, unequal treaties including the annexation documents of 1910 and who had sovereignty over the islands of Tokdo (Takeshima) contested between Japan and Korea. For a recent work on the normalization process in English, see, Jung-Hoon Lee, “Normalization of Relations with Japan: Toward a New Partnership,” Byung-Kook Kim and Ezra F. Vogel eds., The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011). The Park regime utilized the Japanese grants and loan to build the political and economic basis for South Korea’s catch-up development, and to provide compensation to 8,552 victims, 300,000 won each, from July 1, 1975 June 30, 1976. The compensation process was carried out hurriedly and used less than 10 percent of the grant monies. See Shin Un-yong, “Hanil kwagosa munje u hyonhwang kwa gu haekyol mosek,” Kukhwe dosokwanbo (August 2008); Soon-Won Park, “The politics of Remembrance: The Case of Korean Forced Laborers in the Second World War,” Gi-Wook Shin at al eds. Rethinking Historical Injustice and Reconciliation in Northeast Asia (London: Routledge, 2007); William Underwood, “Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages (1): Reparations for Korean Forced Labor in Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 4, Issue 9 (September 2006), p. 3.

Based on an interview on February 8, 2015. The Conference on Forced Labor changed its name to the Network for Forced Labor Mobilization in 2005 and Hida became the co-representative of the network.

On the underground facility, see, Takatsuki “Tachiso” senseki hozon no kai, ’Tachiso’ annai panfuretto (2007); United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Underground Production of Japanese Aircraft, p.57. Also, Sakamoto Yūichi, “’Hondō kessen’ to “Tashiso chika sōko’: Maboroshi no ‘Tachisō sakusen’ ko,” Senō to heiwa, Vol. 4 (1995), pp.19-41.

For detailed discussion on the methods and nature of Korean labor, see, Sakamoto Yūichi,“‘Takatsuki chika sōko’ kōji to rōdōryoku dōin: Senshiki kensetsugyō ni okeru Chōsenjin rōdōsha no seikaku wo megutte,” Historia, No. 152 (1996), pp.133-159.

“Takatsuki kensetsu ni okeru Chōsenjin rōmu – dōsei ni kansuru ken,” by Takatsuki keisatsu shochō to Osakafu keisatsu kyokuchō, June 2, 1945. I thank Mr. Tsukasaki Masayuki for kindly sharing this document.

“Nariai no sengo,” in Muguke no kai, Konnanshite ikitekitanya: Nariai ni okeru zainichi Chōsenjin no seikatsushi (Osaka, 1980/03/31), p. 46. The publication was the result of eight years of investigation by second and third generation Nariai Koreans. They formed a “zainichi Korean circle” named Mukuge (the rose-of-sharon) in 1972. One of their first activities was to collect and print testimonies of the first generation’s wartime experiences.

The Takatsuki Citizens Group is the predecessor to the Tachisō Conservation Association. The group started with about 30 people. At one point their number reached around 80. About 60 members resided in Osaka and more than half of total members were teachers in elementary, middle, and high schools and universities.

Sakamoto Yūichi, “Kusa no ne no sensō wo horu: Sensō kiroku wo nokosu Takatsuki shimin no kai no katsudō, Rekishi kagaku, No. 91 (January 1983), pp. 24-28.

Chantal Mouffe, On the Political (London: Routledge, 2005), p. 3 and passim. One of Mouffe’s central arguments is that “the task of democracy is to transform antagonism into agonism.” Agonism refers to a “we/they relation where the conflicting parties, although acknowledging that there is no rational solution to their conflict, nevertheless recognize the legitimacy of their opponents,” whereas antagonism views the opponents as “enemies who do not share any common ground.” (p.20)