Abstract

The Miike Coal Mine, extending across Omuta and Arao in Kyushu, was an engine for economic growth in Japan until the nation’s defeat in World War II. In 1873, the Meiji government introduced convict labor in the mine. This arrangement continued after the government handed the mine over to a private company, the Mitsui Coal Mine. It was not until 1931, in the wake of the International Labor Organization’s 1930 Forced Labor Convention, that convict labor was terminated. The history of convicts in the mine was not widely known for decades until a local group started restoring memories of it in the 1960s. This paper examines the social and discursive environment in which the recovered history of convict labor evolved.

Keywords: Mitsui Miike Coal Mine, convict labor, commemoration, World Heritage

Introduction

|

Figure 1: Entrance of the Miyanohara tunnel, the Miike Coal Mine. [March 1, 2016] |

The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine, one of several UNESCO registered Meiji Industrial Revolution Sites since 2015 [Fig. 1]. While the central role of the coal industry in Japan’s industrialisation was stressed through the world heritage registration process, the close relationship between pre-war industrialisation and development of the modern penal system, and the use of prison labor, has been less acknowledged. In Miike, use of convict laborers from the nearby Miike shūjikan (central correctional institution) was indispensable for the operation of the coal mine during the early Meiji period.

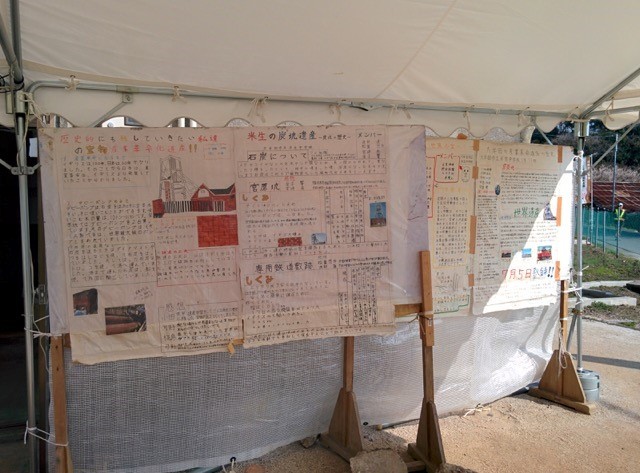

Although the connection between industrialisation and the penal institution was not emphasised during the UNESCO registration discussion, it is widely acknowledged in the local community. At the Miyanohara tunnel entrance, one of the UNESCO registered sites, the official displays show the prisoners at work there. Interestingly, the posters made by junior high school students mention the use of prison labor in the mine [Fig. 2]. There have long been local efforts to preserve the history of prisoner labor in the mines.

|

Figure 2: Posters at the remains of the Miyanohara tunnel made by junior high school students from Omuta that touch upon convict labour in the coal mine. [March 1, 2016] |

The Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation (Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai) is a local group that has attempted to preserve the memory of prisoners’ experience. Beginning in the 1960s with the goal of preserving the convict laborers’ graves, for nearly half a century the Society has been collecting and preserving prisoner experiences. This paper examine the politico-discursive environment in which the society advanced its campaign. Part 1 briefly outlines the introduction of a “modern” penal system and convict labour in Japan. Part 2 delineates the history of convict labour in the Miike coal mine. Part 3 describes the activities of the Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation. Part 4 examines the practice of active members of the Society. The concluding part assesses the historical and contemporary implications of the Society’s activities on the social life of the coal mining town.

1. Emergence of Industrial Prisons in Japan

The idea of confinement as punishment, rather than infliction of pain on prisoners’ bodies, rapidly caught the attention of theorists and practitioners of punishment in the West and its colonies during the late 18th century. However, there was almost no uniform model or blueprint for prisons. Theorists in legal studies offered different interpretations on how to justify punishment such as retribution, rehabilitation, deterrence and incapacitation. Those who designed prison architecture proposed various types of prisons. Jeremy Bentham’s famous panopticon was only one among many proposals made in the first half of the 19th century. A number of experiments were made locally in the West and the colonies. Prisons became experimental sites in which new technologies of control and punishment were tested. In short, prisons became laboratories of social engineering during the 19th century. It was not uncommon for citizens to visit prisons to study these new technologies.

The mid-19th century saw a rapid change in the environment of information transmission. The development of printing, the steam engine, and the telegraph enhanced information circulation. Information on new technologies of governance including those of police, medicine and punishment were exchanged across national boundaries through international conferences, printed texts, and telegraph messages. Circulation of information on prisons through international information networks also began at this time. One of the important sites where such exchanges took place was the International Penitentiary Congress that was held almost every decade since the middle of the century. Thus, local projects for prison development came into contact with those occurring internationally. Thinkers and practitioners of punishment exchanged information on penal practices. Through this robust exchange of information, there emerged a vast archive of penology. Japanese penal practitioners during the Meiji Restoration era started to obtain access to this archive.

The Tokugawa Shogunate and early Meiji government concluded a series of “unequal” treaties with Western powers between 1858 and 1869. The treaties were considered to be “unequal” because they introduced extraterritoriality and denied tariff autonomy to Japan. Revision of these treaties became one of the most important national policies of the Meiji government. For penal practitioners, extraterritoriality was a paramount concern. People from the countries with which Japan concluded “unequal” treaties were exempted from the jurisdiction of Japanese law and subject to the laws of their consular courts. The rationale for this system was the assumption that penal practice in Japan was not adequately “modernised”, that is, it did not adhere to European norms. The Meiji government set out to modernise its penal practices so that offenders could be treated in a “civilised” way. In this discursive game, humanitarian discourse on penology became a political resource in pre- and post-WWII Japan.

At the same time, until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, prisoners were expected to provide cheap and productive labor in many regions across the world. Transportation was a mean to mobilise the labor force. A modern transportation system was introduced in Japan during the 1880s. After the Meiji Restoration, prison administration was placed under the Ministry of Justice (Shihōshō), and later transferred to the Home Ministry (Naimushō), which was established in 1873. The initial purposes of transporting long-term prisoners were to maintain internal security after the Seinan War (1877) and to solve the issue of lack of space in existing prisons. Okubo Toshimichi (1830-1878), then the Home Minister, proposed sending convicts to frontier islands of Hokkaido in 1877.2 Two correctional institutions (shūjikan) were opened in Tokyo and Miyagi in 1879. The Penal Code of 1880 introduced rukei (transportation) and tokei (transportation with labour). Transportation of prisoners to Hokkaido started in 1881 with the establishment of Kabato prison, and penal facilities at Sorachi (1882), Kushiro (1885), Abashiri (1891) and Tokachi (1895) followed. In Kyushu, Miike shūjikan was inaugurated in 1883.3 In Hokkaido, prisoners in Kabato and Abashiri prisons engaged in reclamation and agricultural work. Prisoners who were sent to Sorachi and Kushiro prisons were employed in coal and sulphur mines. In Kyushu, the Miike Coal Mine continuously exploited prisoners as cheap labor during its first 50 years of operation.

2. Convict Labour in Miike Coal Mine and Humanitarian Discourse

Use of convict labor in Miike started before the establishment of Miike prison. In 1873, the Miike coal mine was placed under the central government and the Mizuma prefectural government took care of it in its first few months of operation.4 The prefectural government sent 50 prisoners to the mine to transport coal. In the same year, the central government established the Miike Coal Mine Branch Office and the mine was placed under it. Subsequently, Fukuoka prefecture sent 50 convicts there in 1875, and Kumamoto prefecture sent 50 convicts in 1876. Although the Miike Coal Mine Branch Office urged other prefectures in Kyushu to cooperate, other prefectural governments did not send their convicts at the time. After the Seinan War in 1877, Fukuoka and Kumamoto prefectures withdrew their convicts from Miike, but Fukuoka prefecture soon resent them, and Nagasaki, Kumamoto and Saga prefectures subsequently sent prisoners. In 1883, the Home Ministry of the central government inaugurated Miike prison to which life and long-term prisoners were transported. In 1889, the Miike Coal Mine was handed over to Mitsui, one of the largest zaibatsu business conglomerates in pre-WWII Japan. In the following years, Omuta city flourished as its company town.

The Mitsui Miike Coal Mine continued using prisoners as miners. However, there were voices critical of this arrangement. Within the Home Ministry, Ogawa Shigejiro (1864-1925) argued that the prisoner transportation system was harmful to the security and economy of the neighbourhood close to the prisons. According to Ogawa, the import of prisoners for labor adversely affected the region, interrupted the inflow of respectable people, and aided certain private companies without authorization of the national parliament. Ogawa wrote that it impacted negatively on the purpose of punishment.5 A number of prison chaplains and medical officers also criticised the harsh conditions in which prisoners worked.

In 1889, the very year the company started running the mine, Fukuoka prefecture withdrew its prisoners from Miike. According to the resolution of the Fukuoka prefectural assembly, the major reasons for the withdrawal were the deterioration of health conditions and increasing costs associated with the maintenance of prisoners. Dan Takuma (1858-1932), the general manager of the Mitsui Miike Coal Mine, testified that humanitarian discourse within the Home Ministry was a great obstacle to the pursuit of the company’s business. He wrote “human rights discourse got us in trouble.”6 According to him, the reason Mitsui bought the mine was that the company could expect low-cost labor of convicts.7 The company eventually gained access to convict labor, but had to engage in prolonged negotiations with the Home Ministry.

Although convict labor played a crucial role in infrastructure development in remote areas in early Meiji, it gradually diminished at the turn of the century when cheap labor markets evolved. When Mitsui Miike Coal Mine started its operation in 1889, prisoners were used as miners in Hokkaido, Okinawa, Miyagi, Niigata and Fukushima prefectures. By 1902, however, all the prisons apart from Miike prison had stopped using convict labor in mines. Also in Miike, the Mitsui Coal Mine had to make a decision on the continuous use of prisoners. A contract on the lease of convicts was concluded between the company and the Miike shūjikan in 1898, the first such official contract.8 In 1900, prison administration was transferred from the Home Ministry to the Ministry of Justice.9 Both of the ministries were reluctant to continue exploiting Japanese convict labor in the mine. Although the practice was not terminated at once, the company started seeking labor from the local population and prisoners from Taiwan.10

In Miyanohara tunnel, convicts were physically separated from “respectable” labor by iron bars. According to some testimonies, however, certain communication was secretly maintained among them.11 Although the testimonies reveal moments of “everyday resistance” from the convicts, i.e., escape, insurgency, keeping prohibited articles, brewing doburoku or unrefined sake from secretly kept rice balls, and forming “marital relationships,”12 many stress the harsh conditions under which convicts were forced to work.

However, there was little public criticism of the company for the “inhuman” treatment of convicts in the coal mine in the early 20th century. Kikuchi Tsuneki (1862-?), a medical officer of Miike prison, submitted a written statement in 1900 calling for abolition of prison labor in the mines.13 In his statement, Kikuchi criticised the cruel working conditions of the prisoners, providing statistical evidence of the high mortality rate among convicts working at the Miike mine.14 His statement might have had a certain impact since it was submitted when the company was negotiating with the Home Ministry over the continuation of convict labor in the mine. However, Kikuchi’s argument was dismissed.15 Kikuchi resigned from the prison following the resolution to maintain convict labor in the mine. His criticism had long been forgotten, but it was “rediscovered” in the 1960s as discussed below.

The number of convicts in the mine decreased throughout the Taisho period, 1912-26. Mitsui discovered a new source of cheap labor from Yoron in the Amami Islands.16 Employment of convict labor in the coal mine at Miike was terminated in 1931 following the International Labor Organization’s 1930 Convention on Forced Labor. Miike prison was dissolved and all the prisoners were transferred to Kumamoto.17

Until the turn of the century, for practitioners of penology, there were trade-offs between industrial development and other goals including welfare of the society at large and humanitarian treatment of prisoners. Humanitarian arrangements were important in view of the problem of revision of so-called unequal treaties. Humanitarian discourse provided a common raison d’etre for chaplains and medical officers in the prisons. Images of suffering prisoners were important resources for their efforts to reform prisons . In pre- and post-WWII Japan, technologies and institutions of total war and emergence of the welfare state made possible direct control of individuals in society. In post-war Miike, a new discursive environment emerged including new representations of prisoners.

3. Excavation of Restless Spirits of Prisoners

In the post-WWII period, under the democritisation policies of GHQ and the Allied Occupation, the Miike Labor Union was formed in 1946. In the late 1940s, young union members were strongly influenced by Sakisaka Itsuro (1897-1985) and leftist thought. Sakisaka was a leading Marxian economist from Kyushu University known for translating Marx’s Capital into Japanese. He was born in Omuta city,18 and became active in teaching Marxist thought to workers at Miike in his lectures called Sakisaka kyōshitsu (classroom).19 The young union members who had been exposed to leftist thought played a central role in the Miike Mine Strike in the 1950s.

In post-war Japan, as the major source of energy shifted from coal to oil, the company tried to reduce the size of the labor force because of financial trouble resulting from the national restructuring of the coal industry. The Miike union resisted the restructuring policy leading to the Miike Mine Strike of 1953. The strike lasted for more than 3 months and eventually Miike withdrew the proposal for mass layoffs. In the following years, business conditions further deteriorated. The Mitsui Coal Mine announced a mass layoff again sending dismissal notices to 1,278 workers in December 1959. On January 25th in the next year, the company locked out workers and the union went on strike. The prolonged strike worsened laborers’ financial situation and the union eventually collapsed. Hostility between the original union (now the First Union) and a new Second Union that adopted a cooperative attitude to the company intensified. This changed the political geography of the Miike area completely. The strike ended in August 1960 and the mine resumed operations in December.20

Another traumatic event followed the union movement’s “defeat” three years later. An explosition in Mikawa tunnel killed 458 people and carbon monoxide poisoning severely injured many of the survivors. 839 workers were officially recognized as victims of the poisoning and litigation continued for decades. Suffering bodies of the victims became a part of Miike’s political imagery.21

|

Figure 3: Monument constructed in 2013 commemorating forced Chinese laborers. [March 1, 2016] |

In addition to these traumatic events, the presence of laborers from minority communities made the local political situation more sensitive. After the closure of the Miike prison, more labourers from outside Kyushu, including those from Korea and Yoron in Kagoshima were brought to Miike. Chinese were also imported and forced to work in the mine during the war, as were Allied POWs. Many died in the mines [Fig. 3].22

Although the miners and the company had conflicting interests, there was a common practice that was almost indispensable in their social life in Omuta and Arao, the commemoration of the deceased. A culture of mourning had emerged in Miike before the war. A number of Buddhist temples were built in Omuta and Arao. Monuments to disasters were constructed and memorial services were practiced in the region. A number of stone monuments and tombstones have remained in Omuta. Acts of commemoration became central to cultural politics of Miike from the 1960s onwards [Fig. 4].

Deceased prisoners were rediscovered in this context.23 In Ichinoura graveyard in Omuta city, there were neglected graves [Fig. 5]. The graves are much smaller than most in the cemetery. They are only inscribed with numbers rather than family names as is common in modern Japanese graves. They were locally believed to be prisoners’ graves, partly because of the proximity to the Miike prison. Inhabitants of the area took care of them, but their condition has been deteriorating. In 1965, the inhabitants petitioned Saruwatari Iwao, then a member of the Omuta city council, for repair of the graves. A few volunteers conducted research and eventually held the first urabon’e service24 for deceased prisoners on August 10, 1969. Some 30 members formed Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai (Omuta Society for Preservation of Prisoners’ Cemetery). Society, emphasizing the need to appease the deceased prisoners’ souls, started an annual urabon’e service with the cooperation of the Omuta Buddhist Association, an inter-temple association of Buddhist monks.25

|

Figure 4: Monument commemorating the victims of the 1963 explosion. [April 2, 2016] |

Although the number of members of the association has remained under 50, core members were associated with the Miike Labor Union and the Socialist Party. Urakawa Mamoru, one of the founders of the society, served as secretary of the union until 1953 and then became a member of the Fukuoka prefectural assembly. Another founder, Kosaki Fumihito, was also a secretary of the union.26 The first president of the Society was Motoyoshi Keiji, an economist from Fukuoka University.

Interestingly, some doubted if the graves were actually those of prisoners. In the Kosaki Collection held in the Omuta City Library, there is a document containing letters from Sato Yukio, then a division chief of the Fukuoka Regional Correction Headquarters, to Motoyoshi sent between 1971 and 1972.27 Attached to Sato’s letter dated August 24, 1971 were copied materials for investigation of Ichinoura cemetery. The report concludes that the graves were not likely to be those of deceased prisoners. It speculates that they were probably neglected graves when the cemetery was moved from the previous location in Matsubara to the current site in 1912. Others also criticised the Society for propagating a false belief.28

|

Figure 5: Tombstones at Ichinoura cemetery, Omuta. [April 2, 2016] |

Nevertheless, the Omuta Society for Preservation of Prisoners’ Cemetery continued to claim that the graves were those of prisoners. In 1971, Asahi Gurafu published a special feature article with a few colour photographs.29 Local newspapers have periodically published reports on the “prisoners’ cemetery” in Ichinoura and the yearly urabon’e service.30 In his last publication in 2005, Urakawa expressed ambivalence concerning the authenticity of the graves, but emphasised that “the cemetery was known as the prisoners’ cemetery, and local citizens took special care of it. I dearly wish that they will be preserved in the future.”31 For him, the most important point was to remember the hardship prisoners experienced in the mine.

The society subsequently discovered monuments commemorating deceased prisoners in other parts of Omuta city. On the premises of an individual in Ryugoze, there was a grave marking prisoners’ group burial. The inscription on the read “Tomb of deceased prisoners in Miike kangoku from Fukuoka prefecture” [Fig. 6]. It was moved to the premises of a nearby Buddhist temple Junshō-ji.32

In Katsudachi, there is a monumental stone with an inscription “Gedatsu-tō”. In Miike, use of the term “gedatsu” (moksha or nirvana, i.e., liberation from rebirth, in Hindu / Buddhist philosophy) in the inscription has been considered important. Next to the monument was a well with a concrete cover. Urakawa believed that deceased prisoners’ bodies were thrown into the well without cremation.33 In 1995, the Society repaired the monument and put a statue of Jizō (Kshitigarbha in sanskrit) to appease the restless spirits of prisoners.

|

Figure 6: “Gassō no Hi,” tombstone for prisoners’ group burial, at Junshō-ji, Ryugoze, Omuta. [July 15, 2016] |

The following year, in December 1996, shortly before the closure of the Miike Coal Mine, the bones of more than 70 people were excavated. They were believed to be those of deceased prisoners as the place had been an “abandoned cemetery of Miike prison.”34 The Omuta Society for Preservation of Prisoners’ Cemetery led by Urakawa engaged in the excavation and held a Buddhist memorial service inviting Tani Osamu, then the temple master of Junshō-ji. According to Urakawa, the deceased bodies did not lack body parts and some of the skulls had healthy teeth.35 Urakawa and his society cremated the deceased bodies and built a new monumental stone with an inscription “Gassō no Hi” (monument of group burial) next to the “Gedatsu tō” and the Jizō statue on the hill of Katsudachi [Fig. 7].36 In 1996, the Society also constructed a memorial stone for Kikuchi Tsuneki next to them.37

The society’s act of constructing and preserving monumental stones resonated with the contemporary culture of construction of cenotaphs for workers who passed away in the mine. For the society members, both pre-war prisoners and contemporary workers in Miike were fellow-victims in the process of the modernisation of the Japanese state and accumulation of capital.

|

Figure 7: Monuments at Katsudachi constructed by the Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation. [April 2, 2016] |

4. Recovering the History of Prisoners

Beginning with research on Ichinoura cemetery, active members of the Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation continued studying the history of prisons and prisoners in Miike. It was the period when Omuta City compiled its history in four volumes.38 Its second volume published in 1966 covers the history of convict labor in the Miike coal mine. As Ohara notes, most of the descriptions of convict labor in the volume are quotes from a three-volume manuscript titled Miike Keimusho Enkaku (History of Miike Prison).39 Since the manuscripts were not open to the public then, the newly compiled history of Omuta City offered valuable information to the society members. For example, the second volume included the statement of Kikuchi Tsuneki, which had long been forgotten in public memory.40

From the 1960s, the Society started recovering prisoners’ experiences. Most active was Kosaki Fumihito, who worked for the Miike Labour Union for 33 years as an editor of official union journals. He entered the mine after the war, and became a secretary of the labour union of Mitsui Chemicals in 1949. He was the editor of Sankaro until he retired in August 1966. In October of that year, he was asked to help the Miike Labour Union for “two to three months” as a non-regular staff. The union engaged in negotiations over the termination of medication for patients suffering from carbon monoxide intoxication caused by the 1963 Mikawa tunnel explosion. Thereafter, Kosaki edited the union’s official journal Miike until he became 70 in 1981.41 When he retired from the editorship, he told a newspaper reporter, “I have to rediscover the history of labour movements in Omuta including that of convict labour.”42 By then, recovery of convict labour history had become an important part of his lifework.

Although Kosaki worked for the union, he did not have access to internal company records. As Ohara shows, most of the official records of Miike prison, including its annual reports, statistical records and rulebooks, have been lost.43 Mitsui Coal Mine started compiling its 50-year history in 1944, but in the end it was not published, and the manuscripts became internal records of the company.44 Without access to the archives, Kosaki collected fragmentary records including articles published on journals, including Dainippon Kangoku Kyokai Zasshi / Kangoku Kyokai Zasshi (Bulletin of the Penitentiary Society of the Empire of Japan), and oral history told by former jail staff and local inhabitants. When collecting records, his connection with the union and the Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation was helpful. Urakawa, as a member of the Fukuoka prefectural assembly, collected materials using his socialist party network. Thus, Urakawa and Kosaki created a private collection of historical resources, which provided a base for studies of the history of convict labor in this area. Kosaki enthusiastically wrote articles for newspapers45 and journals.46 In his 1988 lecture,47 he emphasised that convict labor was “indispensable in primary accumulation of capital in this country.”48 He detailed the cruel working conditions of the convicts drawing on episodes from a book written by a former prisoner who served his term in Miike.49

Urakawa developed another means of conveying his message to wider audiences. He did not write many articles in newspapers or journals but self-published a number of pamphlets on the occasions of annual urabon’e service. In the pamphlets, he reproduced historical sources and other materials. For example, his 1995 pamphlet featured the statement of Kikuchi Tsuneki and criticised the cruelty of the state and capital.50 He had a unique editing style not necessarily following academic conventions. In most of his editing, he did not provide bibliographic information. When he quotes texts, he changes typeface freely in order to emphasise some parts. He remixes the original text with other texts, including his own comments, photographs, newspaper and journal articles that are not always closely related to the text. His mashup editing style culminated in his last pamphlet in which he even quoted the calligraphy of the Zen poet Aida Mitsuo (1924-1991).51 Rather than revealing his name as the author or editor of the pamphlets, Urakawa listed the Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation as the creator. In later writings, he displayed a clearly critical attitude toward the unchecked capitalism and regarded the deaths of prisoners as human sacrifice.

Conclusion

In the Meiji period, prisons were expected to serve industrial sites. Prisoners were regarded as laborers who could be required to work under harsh conditions. This scheme was intertwined with the idea of “reform” of criminals and humanitarian goals. The trade-off between productivity and humanitarianism defined the discursive framework in which theorists and practitioners of penology produced massive numbers of texts on prison management.

In the post-war period, most of the industrial sites built by the Meiji government no longer played a central role in the national economy. Manufacturing in prisons was no longer a significant source of profit. Convict labor continues to this day, but it is considered a means of moral education for the convicts, rather than an engine of economic growth. At the same time, prisons have become remote places in the imagined geography of Japanese people. The season of politics of the 1960s and ’70s is over. Today prisons are places only for “criminals” and inmates’ lives are invisible from society.

Now representations of prisoners as politico-cultural resources can be used in different ways. For socialist activists like Urakawa and Kosaki, the silent prisoners of past times, with no contemporary counterpart in the region (there has been no prison in Miike since 1931), could be represented as “pure” victims. Through its representation of the prisoners, the Omuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation could criticize the state and capitalism without touching upon contemporary local politics among workers during and after the 1960s.

The “archives” Urakawa and Kosaki developed through their activities on behalf of prisoners’ cemetery preservation have been donated to the Omuta City Library.52 Ohara Toshihide, who played an important role in the donation process as a librarian and bibliographer, compiled a bibliography. The fragmented history collected by Urakawa and Kosaki has entered the archival network of the 21st century and it will provide intellectual resources for future historians. However, the fragments remain as fragments, as most of the official documents of Miike prison have not yet become available. The Mitsui Coal Mine once compiled its 50-years history with a view to publication, but the manuscripts have been kept within the company following Japan’s defeat in the world war.53 It is likely that the company was and remains sensitive about the effects that the 50-years history could have in post-war Miike and beyond. If the manuscripts had been made public, they could provide valuable sources for Urakawa and Kosaki, for whom writing and editing the history of convict labour and mourning for the deceased convicts were political acts to appeal to workers’ consciousness as victims. The absence of the historical official records and the fragmented nature of Urakawa and Kosaki collections itself are reflections of the post-war political history of Omuta.

|

Figure 8: Commemoration service for deceased prisoners held on July 15, 2016. [July 15, 2016] |

At this time, it appears that Urakawa, Kosaki and their society somehow succeeded in a cultural war of position by donating their collections to the city library. The existence of the collections is institutionally secure. Their society’s annual commemoration service and other activities continue to remind local inhabitants of the experiences of convict victims. As we have seen, the society has imagined Ichinoura cemetery as a symbol of the restless spirits of convicts even though there were doubtful views. Later in Katsudachi, they finally discovered physical bodies of deceased prisoners. The annual commemoration service, now held at Katsudachi and Ryugoze, is carried on by their successors even after the founders of the Society passed away [Fig. 8].

|

Figure 9: Omuta City removed bus timetable boards after round-trip bus service for visitors to the UNESCO-registered Meiji Industrial Revolution sites was terminated on March 1, 2016. [March 1, 2016] |

At the same time, it seems that the meaning of the commemoration has been changing in the social life of Omuta. The Mitsui Coal Mine was dissolved in 1997 and the population of Omuta city has decreased by half. Indeed, the “success” of the Society coincided with the de-industrialisation of the town. Registration of the coal mine as one UNESCO’s Meiji Industrial Sites was expected to boost tourism industry in the region. However, its effect has not been dee[;u felt by the local population thus far [Fig. 9]. If memory of industrialisation starts to lose appreciation as valuable cultural capital, there may be little chance for memories of the dark side of industrialisation to be appreciated. In the years ahead, we will witness how the “recovered” memories of convict labour will adapt to the new discursive environment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my grateful thanks to Irie Yujiro, Ito Masahiro and Ito Miku for introducing me to the community of Omuta. I am especially grateful to Ohara Toshihide, Yamada Motoki and Kajihara Shinsuke for sharing their knowledge with me. I wish to thank Yoshinaga Shinji of Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozonkai for sharing invaluable documents and inviting me to the Society’s annual urabon’e service. I owe a debt to Pan Mengfei for reading my manuscript and giving me suggestions and inspiration.

Notes

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013) / ERC Grant Agreement 312542 and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant Number 15H06192.

Rutokei wo Okoshi Hokkaidō ni Hakken no Gi Jōchin. Naimushō Ukagai 5, Kōbunroku 1877, No. 24 (February). National Archives of Japan.

Clare Anderson, Carrie M. Crockett, Christian G. De Vito, Takashi Miyamoto, Kellie Moss, Katherine Roscoe, Minako Sakata. 2015. Locating Penal Transportation: Punishment, Space, and Place c. 1750 to 1900. In Karen M. Morin and Dominique Moran eds. Historical Geographies of Prisons: Unlocking the Usable Carceral Past. New York: Routledge, pp. 152-153.

Mizuma prefecture was established in 1871 covering the Chikugo region. The prefecture was dissolved in 1876. Part of it was transferred to Nagasaki prefecture and the remaining was transferred to Fukuoka prefecture.

Tokyo Asahi Shinbun (newspaper) dated March 3, 1897 (quoted in Dainippon Kangoku Kkyōkai Zasshi No. 106 (10-3), March 20, 1897, p. 60.

Ko Dan Danshaku Denki Hensan Iinkai. 1938. Danshaku Dan Takuma Den 1. Tokyo: Ko Dan Danshaku Denki Hensan Iinkai, p. 239.

Shūto Saitan Shieki ni Kansuru Keiyaku Teiketsu. Miike Keimusho Enkaku, sono 2. Mitsui Bunko: Kōzan 831-57, pp. 303-306.

Ono Yoshihide. Kangoku (Keimusho) Un’ei 120 nen no Rekishi. Tokyo: Kyōsei Kyōkai, p. 129. Subsequently, in 1903, all the shūjikans and prefectural prisons were designated as kangoku.

The latter attempt was not successful. Shūto tai Ryōmin Kōfu Shieki ni Hōshin Tenkan. Miike Keimusho Enkaku, sono 2. Mitsui Bunko: Kōzan 831-57, pp. 234-240. See also Tanaka Naoki. 1976. Miike Tankō ni Okeru Shūjin Rōdō no Yakuwari. Enerugī-shi Kenkyū Nōto. 6: 152–173.

Kosaki Fumihito (recorded). n.d. Oral Testimonies on Convict Labor 1 & 2. Rare Collections, Ōmuta City Library.

Ibid. See also, Kosaki Fumihito. 1990. Shūjin Rōdō to Ningen (manuscript of Lecture at Tenchi Seikyō).

Mitsui Coal Mine dismissed Kikuchi’s statement arguing that his opinion was based on misinformation. Subsequently, Kikuchi resigned from his position as prison medical officer.

Abe Tadakichi, Secretary of Miike Coal Mine, to Dan Takuma, Director of Miike Coal Mine. May 5, 1902. Miike Keimusho Enkaku. Mitsui Bunko: Kōzan 831-57.

Tanaka Tomoko. 2009. Changes in Labor Policy in the Pre-War Miike Coal Mine and the Resistance of the Workers. The Bukkyo University Graduate School Review. 37: 37-53. [in Japanese

On the termination of lease of convicts in Miike, see Miyanohara Kō to Shūto Shieki Keiyaku Kaijo no Keika. Miike Keimusho Enkaku, sono 3. Mitsui Bunko: Kōzan 831-57, pp. 563-597.

By the later 19th century, the Miike coal mine extended across Omuta, Fukuoka prefecture, and Arao, Kumamoto prefecture.

He recorded his experience at Miike in his book. Sakisaka Itsuro. 1961. Miike Nikki: Tatakai no Riron to Sōkatsu. Tokyo: Shiseidō.

On Miike Mine Strike in the 1950s, see Hirai Yoichi. 2000. Miike Sougi: Sengo Rōdō Undō no Bunsuirei. Tokyo: Mineruva Shobō; Tanaka Tomoko. 2010. Sengo no Miike Tankō ni Okeru Rōmu Kanri to Rōdōsha no Teikō ni kansuru Kenkyū: Miike Tankō ga Naihō shita Mondai ni Chakumoku shite. The Bukkyo University Graduate School Review. 38: 55-71.

On the explosion, see Mori Kota and Harada Masazumi. 1999. Miike Tankō: 1963 nen Tanjin Bakuhatsu wo Ou. Tokyo: Nihon Hōsō-shuppan Kyōkai; Tanaka Tomoko. 2012. Miike Tankō Tanjin Bakuhatsu Jiko ni Miru Saigai Fukushi no Shiza. Bukkyō Daigaku.

William Underwood. 2015. History in a Box: UNESCO and the Framing of Japan’s Meiji Era. The Asia-Pacific Journal. Vol. 13, Issue 26, No. 1 (June 29, 2015).

Commemoration of prisoners who lost their lives in the mine was performed in the Meiji period as well. However, the commemoration discontinued following the closure of the Miike prison. Sugai Masami. 1895. Miike Shūjikan Zaikan-nin Shibōsha Tsuichō Kai. In Shūjin Bochi ni Kansuru Shiryō: Satō Yukio shi Shokan sonota: Ōmuta Ichinoura Bochi Chōsa Shiryō. Kosaki Fumihito Collection. Ōmuta City Library.

Urabon’e is a Buddhist / Taoist festival held on the 15th night of the seventh month of Chinese lunar calendar.

Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai. 2005. Chinkon: Rekishi Tanbō – Fu no Isan. Ōmuta: Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai, pp. 95-96.

Ohara Toshihide. 2015. Shiryō Shōkai: Ōmuta Shiritsu Toshokan ga Shōzō suru Miike Tankō Kankei Shiryō to sono Mokuroku ni tsuite. Enerugī-shi Kenkyū. 30: 99-100.

Urakawa was aware of the criticisms made by Takeda and Shigematsu in 1972. Takeda Takehisa. 1972. Miike Kangoku wo Saguru 5. Keisei. 83-12: 26-27; Shigematsu Kazuyoshi. 1972 (2001). Miike Shūjikan Shō-shi. Privately Printed (reprinted by Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai), p. 27. Copies of the articles are included in Urakawa Collection, the Ōmuta City Library.

For example, Rōjin-kai ga Seisō Houshi: Ichinoura-machi no Shūjin Bochi wo, 6 August 1981, Ariake.

Motoyoshi Keiji. 1971. Chōji: Hōyō, Ryūgoze Bochi, Gassō no Hi, Isetsu. Quoted in Urakawa, op. cit., p. 45.

Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai. 1997. Miike Shūjikan: Shūjin Ikotsu Shōgeki no Hakkutsu, Ikitemo Jigoku Shindemo Jigoku, Shibotsu Shūjin no Matsuro wa Amari nimo Mijime. Ōmuta: Privately Printed Pamphlet.

Urakawa recorded the excavation process with photographs. The photographs are kept in Urakawa Collection, Ōmuta City Library. Permission letters from the Ōmuta City to cremate the bones are included in the collection as well.

Ohara Toshihide. 2016. Shiryō Shokai: Miike Tankō no Shūjin Rōdō. Liberation. 163: 81-101. Miike Keimusho Enkaku was kept by the Mitsui Coal Mine, and was later deposited to the Mitsui Bunko in Tokyo. After the dissolution of the Miike Coal Mine, the deposited records including Miike Keimusho Enkaku were endowed to the Mitsui Bunko.

Ōmuta-shi Shi Henshū Iinkai. 1966. Ōmuta-shi Shi (chu). Ōmuta: Ōmuta City, pp. 599-608. Quoted in Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozonai (ed.), 1995, Miike Tanzan no Shūto Shieki wo Haishi seyo: Kangoku-i Kikuchi Tsuneki no Otakebi, Ōmuta: Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai, p. 15. Also quoted in Ishikawa Tamotsu, 1997, Miike Shūjikan Monogatari: Miike Tankō Hatten no Kiso, Ōmuta: Ishikawa Tamotsu (privately printed), p. 39. The letter is frequently referred to in writings of those who are associated with the Ōmuta Association for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation.

Na mo Nai Hikage no Shiorebana, Kyōsei Rōdō ni Hateta Shūjin, Miike Tankō. December 25, 1981. Mainichi Shimbun (Chikugo edition).

Rōso Kikanshi Tsukutte 33-nen Miike Rōso no Kosaki-san Yūtai. December 25, 1981. Yomiuri Shimbun (Chikugo edition).

Some of them have been discovered thanks to the efforts of Kosaka, Urakawa, Ohara and others who were associated with the Ōmuta Society for Prisoners’ Cemetery Preservation. See Ohara, 2016, op. cit.

Hand copied draft 50 years history is now kept in Mitsui Bunko and Ōmuta City Library. Mitsui Kōzan Gojū-nen Shi Kō. 1944. Mitsui Bunko. The copy kept in Ōmuta City Library is likely to be a hand copy of the one kept in Mitsui Bunko. Ohara, 2016, op. cit., p. 97.

For example, He published serial articles on convict labor on Ariake Shimpo in 1976. Kosaki Fumihito. 1976. Miike Tankō Shūjin Rōdō no Hanashi 1-14. Ariake Shimpo. He wrote similar serial articles from time to time mainly on Ariake Shimpo. For example, Kosaki Fumihito. 1982. Shūjin Rōdō Iseki wo Tazuneru 1-11. Ariake Shimpo; 1987. Kangoku-i Kikuchi Ishi no Koto 1-5. Ariake Shimpo.

One of his early articles on convict labour was co-authored with Motoyoshi. Motoyoshi Keiji and Kosaki Fumihito. 1978. Miike Tankō no Shūjin Rōdō: Chitei ni Umoreta Hitotsu no Rekishi. Fukuoka Daigaku Kenkyūjo Hō. 39: 79-156. Later, he kept writing for journals related to convict labor as well as the CO poisoning issue. Kosaki Fumihito. 1982. Shūjin Rōdō no Rekishi: Miike Tankō wo Chūshin ni 1-5. Rōdō Keizai Junpō. 36-1226: 30-33, 36-1227: 32-34, 1229: 26-28, 1230: 22-27, 1232: 23-24; Kosaki Fumihito. 1983. Shūjin Rōdō no Jittai to Kon’nichi teki Igi 1-4. Gekkan Sōhyo. 305: 58-64, 306: 77-83, 307: 86-94, 308: 88-94.

Manuscript of the lecture and other related memoranda and papers are kept in the Kosaki Colletion of the Ōmuta City Library. Kosaki Fumihito. 1988-07-16. Miike Tankō Shūjin Rōdō wo Oitsuzukete. 13th Study Camp for Students of National Universities in Kyushu (Ōita).

The Kosaki collection was donated to the library in 1997 and the Urakawa collection was donated around 2005. Ohara, 2015, op. cit., p. 100; Ōmuta Shūjin Bochi Hozon Kai, 2005, op. cit., p. 109.