Introduction

Four decades of rapid economic growth in China has come at a huge price to the environment, from smog-ridden skies to contaminated rivers, toxic soils and “cancer villages”. These increasingly intolerable costs have emerged as a major source of social unrest in recent years. Premier Li Keqiang acknowledged this in his opening address to the National People’s Congress (NPC) on 5 March 2015: “China’s growing pollution problems are a blight on people’s quality of life and a trouble that weighs on their hearts”.

|

A still from the documentary Under the Dome with Chai Jing in the foreground. Photo: cq.house.qq.com |

Six days before Li’s opening address, on 28 February, the former investigative journalist Chai Jing柴静released her documentary Under the Dome穹顶之下on the Chinese Internet. Under the Dome vividly conveyed the nature of this “blight” and clearly struck a chord: its mainland Chinese audience exceeded 200 million people. Yet within two weeks of its release, it was no longer possible to download the film in China, and official directives prohibited the Chinese media from any further reporting on the film. It is still available on YouTube but, of course, this is also blocked in China.

Clearly, the detailed, inconvenient truths laid bare in Under the Dome were too much for the Chinese leadership to handle. And it wasn’t hard to see why. The film implicated party-state officials at every level in its highly critical assessment of the “growth at all costs” industrialisation strategy of the last four decades. Its overarching message was loud and clear: that the central government was primarily to blame for blatantly failing to enforce its own environmental laws and regulations and call polluters to account. Whether either Premier Li or President Xi Jinping had seen the documentary, they seem to have gotten the message. Xi declared in his own address at the NPC meeting on 6 March that, “We are going to punish, with an iron hand, any violators who destroy the ecology or the environment, with no exceptions”.

The Plan: Green from the Top Down

Fortunately, this is not Xi Jinping’s government’s only strategy for addressing China’s environmental crisis. The central government has produced an abundance of plans to tackle China’s environmental problems during the period covered by its 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-15), and ramped up its efforts following Premier Li’s declaration of a ‘war on pollution’ in 2014. In November 2014, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) 国家发展和改革委员会 released the National Plan for Responding to Climate Change (2014) 国家应对气候变化规划. This plan outlines strategies including strengthening laws and regulations on climate change and limiting large-scale industrialisation and urbanisation. It also proposes defining “ecological red lines” (a baseline level of ecological health that must be maintained) for key areas including the headwaters of the Yangtze and Yellow rivers. Other strategies include limiting total coal consumption, and proactively promoting cleaner energies. The language of strengthening, limiting, defining, controlling and promoting is indicative of the central government’s intention to drive China’s climate change agenda from the top down.

In February 2015, the NDRC published its roadmap for a nationwide emissions trading scheme (ETS). This will build on the seven pilot programs that have been implemented since 2013 in Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Shenzhen and Tianjin as well as Guangdong and Hubei provinces. Together they comprise the second largest ETS in the world after that of the European Union. The national scheme, to be launched in 2017, will create the world’s largest carbon market, and by a big margin.

In his March 2015 report to the NPC, Premier Li committed the government to a wide range of specific energy conservation and emission reduction measures as well as environmental improvement plans and projects. These support China’s official quest for “green, low-carbon and recycled development” 绿色低碳循环发展, the catch-phrase for its environmentally-friendly growth strategy. They include an action plan for preventing and controlling air pollution, upgrading coal-burning power plants to achieve “ultra-low” emissions similar to those produced by gas, promoting clean-energy vehicles, and improving fuel quality to meets the new National V standard by which the sulphur content in fuel must be less than ten parts per million. There are also ambitious plans to develop renewable energies including wind power, photovoltaic power, biomass energy and hydropower, as well as safe nuclear power. Li also announced that the energy conservation and environmental protection industry would become a “new pillar of the economy” 经济新支柱 and that “green consumption” 绿色消费would become the path to stimulating the domestic consumer economy.

The following month, the Chinese government committed to establishing a “green financial system” 绿色金融体系. A report produced by experts from the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), the China Banking Regulatory Commission, the Ministry of Finance, other Chinese banks, the Chinese Academy of Social Science, universities, think tanks and more laid out the blueprints for this system. In his foreword to the report, Pan Gongsheng潘功胜Deputy Governor of the PBoC refers to the “opportunity” he had to watch Under the Dome, an interesting choice of words. In a key passage, he reinforces the message that in China, change must come from the top down: “For policymakers, these worsening environmental problems require the further enhancement of top-level design and the improvement of market mechanisms and policy support systems, so as to provide the conditions necessary for various stakeholders to participate in environmental management and protection”.

China also introduced countless plans to tackle climate change on a global level in 2015 in the period leading up to COP21 – the Conference of Parties meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – in Paris in December. In June, China submitted its “Enhanced actions and measures on climate change” to the UNFCCC Secretariat. These provided the basis for the country’s “intended nationally determined contributions” (INDC) to the negotiations. They set out the target of reaching peak CO2 emissions around 2030. By that time carbon intensity (CO2 emissions per unit of GDP) would be reduced by sixty to sixty-five percent from 2005 levels and the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption increased to around twenty percent from the current level of 11.2 percent.

The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) – the first one produced under the leadership of Xi Jinping – will solidify these plans and more when it is formally adopted in March 2016. The draft proposal, released in November 2015, names the environment one of five key points of the economy. It stresses green and sustainable development and the Party’s intention to promote a low-carbon energy system. It is possible that a cap on coal use or a ban on new coal-fired power plants will become part of China’s long-term development strategy. Given its global economic clout, a greener China could become a catalyst for worldwide change.

The Reality: smog from the bottom up

As Under the Dome made abundantly clear, rules, regulations and plans have so far failed to green China. The documentary exposed both industry and local governments’ notoriously low compliance with central government regulations, pointing to problems at every level. These include coordinating action among ministries with conflicting interests; the blind pursuit of rapid economic growth by provincial governments; the vested interests of powerful, corrupt and monopolistic state-owned energy and power companies; and the self interests of tens of millions of new car owners, many of whom run their vehicles on low-standard fuel that fails to reach national standards. As Chai succinctly sums it up: “no regulations, no authority, no law enforcement – the conundrum of environmental protection right there”.

One of many damning examples Chai Jing uses to illustrate her point begins with a visit to a truck tolling station, where trucks are checked to see if they are complying with emission standards. Many of the truck drivers fail the test. In one case witnessed by Chai, the official in charge does not impose the requisite on-the-spot fine because he notes that the truck is carrying food that is part of the city’s supply system – and local regulations stipulate that such transport cannot be disrupted.

Chai Jing then reveals a thriving industry for “fake cars”, vehicles manufactured without the required emission controls devices in the first place, and which produce emissions that are 500 times the national standard. In theory, the Atmospheric Pollution Prevention Act 大气污染防治法 of 2002 could be used to shut down the manufacture of such cars, but Chai discovers that no government department has been charged with enforcing the act. She records an official at the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) saying, “As far as we know, it’s not us”. One from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology tells her, “It’s definitely not us”. A third from the General Administration of Quality Supervision and Inspection insists, “It should be all three of us”. Finally, she calls an official at the National People’s Congress who tells her: “The issue of the execution of this law is indeed unclear”. He acknowledges that they’d made it that way on purpose because so many government departments opposed the act. The result puts manufacturers in a corner. As one of the factory owners explains: “If we build real trucks and others build fake trucks, we would be bankrupt tomorrow”. An MEP official admits, “Not enforcing the law forces people to cheat”.

|

According to Under the Dome, Beijing’s daily PM2.5 level is five times that of China’s average. Photo: fotomen.cn |

Chai then turns to the issue of why Chinese fuel standards are set so low compared to those elsewhere. She asks why fuel required to reach the then-highest National Standard 4 was still in such low supply, accounting for just three percent of all available fuels. Yue Xin 岳欣, a Director at the Chinese Research Academy of Social Sciences informs her that representatives of China’s oil industry dominate the standards committee. Neither the MEP nor the National Development and Reform Commissions (NDRC) have the power to enforce higher standards. Baffled, Chai Jing questions Cao Xianghong 曹湘洪, Head of the National Fuel Standards Committee and former Chief Engineer at the state-owned China Petrochemical Corporation (Sinopec). Cao defends the role of the oil industry in setting fuel standards because, he tells her, he doesn’t believe that people from the MEP understand the oil refining business

As if that unblushing insult to the state ministry tasked with China’s environmental protection weren’t enough, Cao then addresses the question of whether Sinopec, the second largest company on the Fortune Global list in 2014 and described by Fortune as the “king of China’s state-owned hierarchy”, should have to take greater responsibility for its impact on the environment. As he puts it: “Sinopec is huge, like a person, very big, but it’s all fat and no muscle”, clearly implying a lack of capacity and willingness to tackle China’s pollution problems.

Chai Jing then addresses the issue of corruption in the energy industry’s relations with the party-state. Citing the views of an official convicted for corruption, she describes the links forged in recent years between people in the National Energy Administration, Sinopec, electricity distribution firms and the coal and mining industries. The film raises serious questions about Sinopec’s involvement in setting the standards for fuel that it both produces and sells in a highly concentrated, state-dominated market.

Other stories told in Under the Dome illustrate the connection between industrial emissions and the “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable” development model of the past. The film also highlights the urgent need for China to rebalance its economy away from energy-intensive production, as well as to price energy according to market principles, eliminate subsidies for ‘dirty’ industries, and tackle powerful SOEs (like Sinopec) whose vested interests are at odds with the central government’s green growth agenda. While the plans for action announced in 2015 are encouraging, clearly far more remains to be done.

A Case of Consumption

Within days of the release of Under the Dome, the newly appointed Minister for Environmental Protection, Chen Jining, praised its “important role in promoting public awareness of environmental health issues”. He saw it as encouraging individuals to play their part in improving China’s air quality. In fact, very little of the film focuses on the responsibility of individual citizens, until the concluding ten minutes when Chai Jing notes that “Even the most powerful government in the world can’t control pollution by itself”. Turning her attention to the choices made by “ordinary people, like you and me”, she urges her viewers to take public transport, walk, ride bikes, and avoid burning low-quality coal, as well as to report polluters and boycott the goods of listed polluting manufacturers. According to Chai Jing, with collective action, and “a little thought and care, the smog will start to clear”.

If only it were that simple. China’s plan to rebalance the economy towards domestic consumption is coupled with its National New-Type Urbanisation Plan (2014-2020) 国家新型城镇化规划, which aims to raise the urban proportion of the population from fifty-three percent in 2013 to sixty percent in 2020. If successful, this will create a middle class the size of which the world has never seen before. The global environmental consequences of hundreds of millions of new urban consumers will be unavoidable and immense – whether their rising demand is satisfied by China’s domestic production or elsewhere.

The number of cars in China has increased by around one hundred million in the last decade. In cities including Beijing and Hangzhou, car emissions are now the primary source of PM2.5. The Development Research Centre of the State Council predicts that there will be 400 million private vehicles in China in fifteen years time. Car owners don’t only consume energy directly in the form of petroleum at the pumps. The production of cars requires energy as an input, and other inputs that use energy as an input (most obviously steel), and so on down the chain.

Individuals consume energy directly in the form of coal, natural gas, petroleum and electricity and indirectly through the many goods and services that require energy. Indirect energy consumption – and associated emissions – is likely to grow substantially in China in the years ahead.

Meng Xin and I calculated the direct and indirect energy use and subsequent emissions per capita of 33,000 urban Chinese households. The figure below illustrates the results, plotted across income percentiles (ranging from the poorest to the richest one percent of the sample population). As seen, total energy consumption, and therefore emissions, increases as income rises. This may be an obvious point: richer people have more to spend, so they tend to consume more of just about everything. But people can only consume so much energy directly, no matter how rich they are. More importantly, we show that indirect emissions rise even more when income increases. At higher levels of income, indirect emissions are an even greater problem than direct emissions.

On the other hand, consumer choices can change, and production technologies and environmental policies can make the production of all goods and services greener over time. Given its population size, and its global emissions ranking, no country has a greater incentive than China to turn this potential into reality. Yet it needs to make serious efforts to address fundamental issues like the legal ambiguity, bureaucratic buck-passing and corporate bullying described above. Otherwise it is highly unlikely that a program of promoting a “green, low-carbon, healthy and civilised way of life and consumption patterns” together with the kind of personal activism advocated by Chai Jing will be enough to tackle the country’s complex environmental crisis.

|

Figure 1. Household per capita emissions by income percentile |

Under which dome?

Chai Jing borrowed the name Under the Dome from a US television series about a small town upon which a dome descended out of nowhere, cutting it off from the rest of the world, providing no way out. Yet this is not a perfect metaphor for China’s reality. In an increasingly integrated global economy – in which China is both the largest exporter and one of the largest overseas investors, we are all effectively living under the same dome.

The Chinese government played a critical role at the COP21 meeting that, as the official agreement states, marked “a change in direction, towards a new world”. The Paris agreement confirms the target of keeping the rise in global temperature below 2°C, and ideally 1.5°C, with 186 countries publishing action plans for achieving targeted reductions in green house gas emissions. The agreement asks all countries to review these plans every five years beginning in 2020, not to lower their targets where possible, to reach peak emissions “as soon as possible” and to “achieve carbon neutrality in the second half of the century”.

|

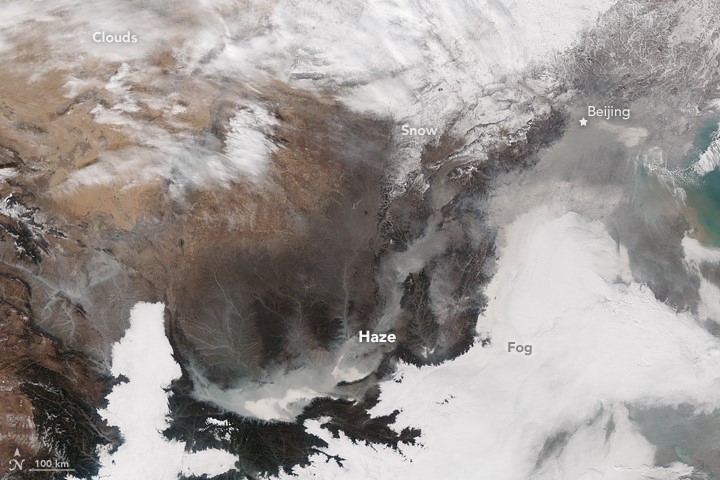

November 2015: As world leaders converged on Paris for the World Climate Change Conference 2015, residents of Beijing and other cities in eastern China faced the most severe air pollution the nation saw that year. Photo: earthobservatory.nasa.gov |

The impetus for finding a global solution to what is clearly a global problem gathered momentum in Paris. Yet the challenges of implementation remain huge, for at least two reasons.

First, in all of its policy documents, China stresses its status as a developing country and the principles of “equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”. These principles were a dominant theme at the 20th BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) Ministerial Meeting on Climate Change in June 2015. The ministers collectively called on developed countries to take the lead in emission reductions and provide financial support to developing countries for green technology and capacity building, as well as mitigating against and adapting to climate change. COP21 confirmed that developed countries remain committed to raising US$100 billion per year by 2020 from public and private sources to address the needs of developing countries. Yet developed countries have collectively failed to provide this funding since 2010 when the commitment was first made – falling short, according to World Bank estimates, by about US$70 billion per year.

Second is what is known among economists as the “pollution haven hypothesis”. This suggests that foreign investors will be drawn to countries where environmental regulations are weak and production costs relatively low. As China tightens up on its own environmental regulations, its ‘dirty’ industries are likely to try and relocate offshore. There’s no reason to think that the Chinese multinationals will be any better than Western ones at resisting the option of looking for ‘pollution havens’. These are most likely to be found in other developing countries, where the urge for stronger environmental regulation often loses out to the pressing need for economic growth.

This hypothesis will be tested as China rolls out its Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路, abbreviated in English as OBOR. OBOR aims to enhance China’s connection and cooperation with other parts of Asia, Europe and Africa through increased regional trade as well as cultural exchange. It requires the construction of an infrastructure network, including new ports, railways, roads and so on throughout the region, as well as improvements to existing infrastructure. This will by its very nature be energy intensive, just as China’s internal infrastructure expansion has been in the past. While official policy documents stress that the initiative will “promote green and low-carbon infrastructure”, it will take concerted bilateral and multilateral efforts to turn these ambitions into reality.

The problem of “pollution havens” extends beyond developing countries. In 2014, then Australian prime minister Tony Abbott publicly stated that coal is “good for humanity”, and the “foundation of prosperity for now and the foreseeable future”. This was the opposite view to that of the United Nation’s top climate official, Christiana Figueres, who warned that most of the world’s coal must be left in the ground if we are to prevent catastrophic global warming. Abbott’s pronouncement, and his climate change policies generally, received much criticism both within Australia and overseas, including from China. Yet even Abbott’s successor as Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, who once supported the introduction of an ETS, now appears to shares his predecessor’s aversion to “green tape” (environmental-based regulations). The Turnbull government has given conditional approval to the Chinese state-owned company Shenhua Watermark to open a highly controversial coalmine in the fertile Liverpool Plains area of New South Wales. Shenhua, which is the world’s largest coal supplier, plans to invest A$1.2 billion in the mine, from which it intends to extract ten million tonnes of coal per year for thirty years. Unless there is an unexpected change in policy direction, Australia could soon find itself home to some of China’s dirtier industries.

On 8 December, as 2015 was drawing to a close, the Beijing authorities issued the first “red alert” for air pollution since the introduction of an emergency response system in late 2013. A red alert – declared if Air Quality Index readings of PM2.5 exceed 200 milligrams per cubic metre or more for at least three days in a row – places temporary restrictions on the city’s cars, factories and construction sites and shuts down schools. Critics accused the city’s environment bureau of taking too long to issue the alert, given that in the week preceding it PM2.5 levels had been close to 1000, 40 times the World Health Organisation’s guideline for “maximum health exposure” of 25. But its ultimate decision signalled that it was capable of choosing the environment over the economy, at least in desperate circumstances.

The rhetoric of the highest levels of government, including its threat of “iron-handed punishment” for environmental lawbreakers, signals a sincere interest in tackling China’s environmental problems. Yet without a more systemic program of environmental management within China, similarly strong commitments by all the nations of the world and substantial personal efforts on the part of the world’s 7.3 billion individuals (especially the billion or so richest ones) it is hard to imagine how we will ever escape from “under the dome”.

|

December 2015: Chinese authorities issue their first ever ‘red alert’ for Beijing as acrid smog enveloped the capital. Photo: bj.jjj.qq.com |

Postscript: 28 October 2016.

While there was plenty to feel negative about in 2015, and particularly following the damning evidence presented in Under the Dome, 2016 has delivered many positive environmental outcomes for China, and the world as well. In early September, China announced its ratification of the Paris climate change agreement, which needed to be ratified by 55 countries, representing 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions, for it to come into effect. This goal was reached on 3 October 2016, with China’s decision clearly encouraging a large number of countries to follow suit – as of 5 October 2016, 81 countries had ratified the convention. On 4 November 2016, thirty days after the country target was reached, the Paris Agreement entered into force. While the naysayers will criticise the Agreement for its lack of binding targets, this is surely a step in the right direction for global environmental change.

Domestically, the release of the 13th Five-Year Plan in March 2016, as noted above, strengthened China’s commitment to developing a low-carbon green economy, and there is ample evidence to suggest that this commitment is real. A Greenpeace article in May 2016 declared that “China’s 13th Five-Year Plan is quite possibly the most important document in the world in setting the pace of acting on climate change”, noting that “2020 energy targets that would have seemed quite meaningful or even ambitious a few years ago have now become redundant”. Of the many figures they provide to support this claim, the share of coal in the total energy mix is expected to fall below 63% in 2016, a one percentage point annual drop since 2010, and only one percentage point above the target of 62% for 2020.

The greatest signal for hope lies in China’s advances in renewable energy, or in what John Mathews described in a recent Asia-Pacific Journal article as “China’s continuing renewable energy revolution”. Building on his previous work with Hao Tan, in which they argued that China has “overwhelming economic and energy security reasons for opting in favour of renewables, in addition to the obvious environmental benefits”, Mathews shows that through 2015, China’s electric power system was still “greening faster than it is becoming black”, in terms of electric power generation, new generating capacity and investment. If current trends continue, he argues that China “would be the world’s undisputed renewables superpower – and one that is well on the way to becoming the world’s first country to become a terawatt renewables powerhouse – by the early 2020s”. The numbers he provides to back up this claim are truly impressive. If – and it’s a large if – China can export these trends to its OBOR partners and beyond, the international benefits could be tremendous.

China’s reform and development experience in the past four decades has been far from perfect. Many people remain highly critical of the government’s “growth at all costs” approach during that time and will continue to argue that recent developments are too little too late. However, it could be argued that the Chinese government’s commitments on paper, combined with mounting evidence that positive change is happening on the ground, demonstrate a capacity to drive the greening of the economy to an extent that green supporters in advanced democratic countries (and I have Australia primarily in mind) can only dream about. It may be a long shot, but as of October 2016 I’d still place my money on the Chinese government to play a positive role in “lifting the dome” in the decade ahead, both domestically and internationally as well. Given an increasingly environmentally aware public, whose demand for greener living will only increase with time, the preservation of Party power is at stake: and that’s the best incentive of all.

|

Will Beijing escape from underneath its “smog dome”? Photo: Ernie/Flickr |

An earlier version of this article was published in the China Story Yearbook 2015, an annual publication produced by the Australian Centre on China in the World at The Australian National University in Canberra. The 2015 volume is titled Pollution, expressed with the Chinese character 染 ran, and explored the broader ramifications of ‘pollution’ (in its various guises) in the People’s Republic for culture, society, law and social activism, as well as the Internet, language, thought and the economy. My chapter, named after the phenomenally successful documentary Under the Dome, explores the multi-layered environmental challenges facing the world’s largest population under the control of the most powerful one-party state, presenting many reasons for despair but also a glimmer of hope.

Related articles

• John A. Mathews, China’s Continuing Renewable Energy Revolution – latest trends in electric power generation

• Nathan Nankivell, China’s Pollution and the Threat to Domestic and Regional Stability

• Yokemoto Masafumi, Hayashi Kiminori and Oshima Ken’ichi, Overcoming American Military Base Pollution in Asia: Japan, Okinawa, Philippines