|

Introduction

Recently, the influential American political pundit, Bill O’Reilly, demonstrated that no nationality or ethnicity holds a monopoly on retrograde views of slavery, on what it means as a human being not to have possession of one’s own life. In response to first lady Michelle Obama’s evocative observation that her African-American daughters were growing up in a house built by slaves — a house, moreover, they loved — O’Reilly tried to negate this moment’s deep significance by quipping that the slaves who built the White House were “well fed and had decent lodgings.”

In light of O’Reilly‘s remark, Mrs. Obama’s call that “when they go low, we go high” remains broadly applicable.

Noticeably, writer/producer Yang Ching Ja has taken the first lady’s dignified approach in a critique of Park Yuha’s work on the issue of Japanese military sexual slavery during World War 2. Lucidly translated from Japanese into English by Miho Matsugu, Yang makes clear how best to “do” this history: recognize its victims and build from there; premise their memories through the lens of traumatic experience; and contextualize such evidence in a larger context of related memory and documentary materials, such as soldiers’ testimony, government orders, maps, photos, and so on.

This is truly important. Collectively, we are at a point in studying the issue of Japan’s wartime system of state-sponsored militarized sexual slavery that as researchers and observers of East Asia’s past and present we can know the basic contours of this history’s cruel euphemism, “the comfort women.” Still urgent nonetheless — and what Yang powerfully accomplishes — is to focus on the centrality of the people deprived of their humanity, trapped within this system.

At no moment has this been more pressing. The substance of the so-called December 28, 2015 comfort woman agreement is being put to the test. The end of the year announcement —amounting to a joint press conference more than a binding statement since no one signed anything —committed both countries to acknowledge the truth of the victims’ claims and to move forward beyond their open wrangling over this history through establishment of a fund that would be used to alleviate the pain of the 40 surviving Korean women. Much to the outrage of many involved — not least the victims of this history — the foreign ministers of both countries have argued that with this declaration, “the issue is resolved finally and irreversibly.” Watanabe Mina, secretary general of the Tokyo-based Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace, suggests a more inclusive way to understand the moment’s possibilities: although it will not restore the victims’ honor, “nonetheless (we) need to capitalize on the agreement (to make it work for the victims) because we have worked thus far.”

|

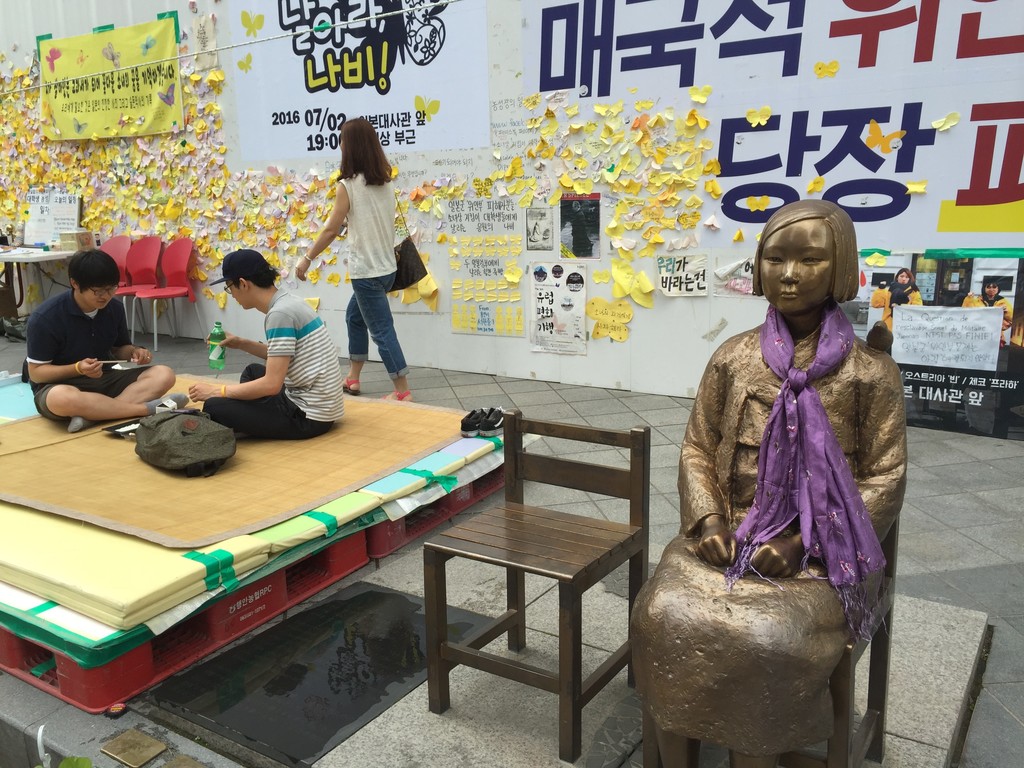

A “comfort woman” statue outside of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. Japan demands the removal of the statue, while there have been major protests against its removal by supporters of the “comfort women” in South Korea. Photo by Alexis Dudden. |

All things considered, matters boil down again to the actions of the perpetrator state: Will Tokyo supply the roughly 10 million dollars it has promised, or will it continue to find reasons to renege? For the past 25 years, private and quasi-governmental groups in Japan have contributed money to the surviving women’s well-being, yet the Japanese government continues to maintain that the matter of legal reparations is unrelated and long settled. Now, it wants to make clear that any money it contributes forgoes the matter of state responsibility.

Several United Nations committees are concerned. These groups hold that the history of Japanese state-sponsored militarized sexual slavery constitutes a crime against humanity as spelled out in Security Council Res. 1820. Vitally, the international body does not accuse Japan today of committing these crimes; instead it is signaling that all humanity can learn to move forward by addressing the truth of the past.

Yang Ching Ja’s ruminations on Park Yuha’s story-telling underscore that we begin to do this through empathizing with the horror endured by those enslaved in systems from which there was no escape. We do not explain away the past to make it more palatable to us today. AD

|

Panelists at the panel discussion, “Can Perpetrators Talk about ‘Reconciliation’?” at Seventy Years After the War: East Asia Forum on August 14, 2015. From the left, Watanabe Mina (Women’s Active Museum of War and Peace), Yang Ching Ja, Ukai Satoshi (Hitotsubashi University) and Uta Gerlant (The Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future). Photo provided by Yang Ching Ja. |

Park Yuha’s Teikoku no ianfu: Shokuminchi shihai to kioku no tatakai or Comfort Women of the Empire: The battle over colonial rule and memory (Tokyo: Asahi shimbun shuppan, 2014) deserves critique from multiple and comprehensive perspectives. Here, I would like to focus on one thing: her failure to fully recognize the victims.

|

Park Yuha’s Comfort Women of the Empire: The battle over colonial rule and memory |

I am deeply concerned about the way this book has been revered by “liberal” intellectuals and media ever since its publication in Japan in 2014. One positive review hailed it as “listening to the voices of different and various individual women” who were forced to become “comfort women,” and asserted it to be a “lonely” job to “fairly” face one’s own country (South Korea)’s nationalism (Takahashi Gen’ichiro, “Rondan jihyo: kodoku na hon, kiokuno shujinko ni narutameni” [Op-Ed: A Lonely book: to become the main character in her memories], Asahi shimbun, November 27, 2014).

Here is a passage in the book that I believe corresponds with the assertion that it reflects the voices of a wide variety of comfort women:

“To conceal any memories that don’t show the comfort woman as victim is to ignore the comfort woman’s whole personality. It is also to deprive her of the right to be ‘master’ of her own memories as a comfort woman. If we allow them only the memories that others expect them to have, we are in some sense, forcing them into subordination” (143).

I can completely agree with her way of thinking here. I believe, however, that this is how all of us who have supported the victims have interacted with them — myself included.

That is why I cannot agree when Ms. Park Yuha writes elsewhere in her book, “their voices were ignored by their supporters” and “[the supporters] have been highly selective about which memories to include publicly” (101).

Park argues that unlike victims of other aspects of Japan’s occupations, Korean comfort women as “the comfort women of the Japanese empire” had a “comradely” relationship with Japanese soldiers (83-84). To support her argument she uses numerous quotes not only from novels but also from Korean Comfort Women Who Were Forcefully Drafted by the Japanese Army,2 a collection of testimonies by former Korean comfort women edited and published by the Korean Council, which is the focus of her criticism, and the Research Association on the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery.

The Korean Council has tried to listen sincerely to the testimony of the victims and present it as truthfully as possible, an effort that has culminated in a six-volume publication. The extent of that effort is why Ms. Park was able to find passages recounting some women’s romantic feelings for Japanese soldiers or an occasional recollection of a happy time. The blurb on the cover of Park’s book says that the author “carefully selected testimony by former comfort women,” but the truth is that Comfort Women of the Empire is a book in which the author “carefully selected” only those parts of the collection that fit her own argument. If I may borrow the author’s words about The Korean Council, she is “selecting” from the victims’ testimonies. This is, in my view, what is “abusive” about her approach.

It’s not just the way she picks and chooses from the testimony, but the way she reads the bits she focuses on. Ms. Park seems to read the testimony as if she were critically reviewing a literary work. But her approach reveals her lack of imagination and poor comprehension of the contents.

Does the Testimony in the Animated Herstory Erase Her “Spontaneity”?

Let me give an example. Consider the 3D animation entitled Herstory,3 which is both about and narrated by a former Korean comfort woman, Chung Seo-Woon.4 Ms. Park asserts that the animation deliberately erases the voice of Ms. Chung when she says she “voluntarily” or jibunkara went to become a comfort woman (151), but this is wrong.

The original animation has her saying “That is why I said I would go and I did.” The full quote is included in the Korean subtitle too. The Japanese subtitle simplifies it as “I ended up saying I would go,” but it retains Ms. Chung’s voice and does not erase it.

On top of that, Ms. Chung explains in Herstory that she went “voluntarily” because she was told that her father, who was arrested when he refused to donate his brass dishes to the Japanese military, would be released if she went to work for a factory, and she believed it. It is beyond my understanding how anyone could interpret this chain of events as “voluntary.”

Moreover, the very idea that the degree of harm depends on whether the victim went voluntarily or was forced has acted as a silent pressure against victims speaking the truth. The true nature of the “comfort women” problem is the serious violation of human rights by a state that uses women’s sexuality as a tool in war. Even if a woman decided by herself, or even if she went knowing she would be forced to become a “comfort woman,” the state cannot be acquitted of responsibility for what it did to her. That is the reality that we who have engaged in what we call the Movement to Resolve the Issue of Japan’s Military Comfort Women have found through our activism over the past quarter century.

An Appalling Interpretation of Testimony over Opium

The South Korean court ordered the author to eliminate the following passage from Park’s descriptions of the animation in Comfort Women of The Empire5:

“Certainly opium must have been an instrument to forget the pain she had everyday. But according to their testimonies, the women were using opium provided directly by their ‘owners’ and brokers. When they used opium with soldiers, I have to say that it was rather for the purpose of pleasure.”6

I was appalled when I read the Korean version of Comfort Women of the Empire for the first time. No wonder, I thought, that the grandmothers at the House of Sharing7 filed a lawsuit after discovering passages like this in the book. The Japanese version also says “While opium lessened the physical pain, it was sometimes used to enhance their sexual pleasure” (151).

Ms. Park relies on two different passages from the collection of testimonies as the basis for her interpretation. Only one seems to ground her descriptions:

“Soldiers secretly injected me. They said that it would feel very good to have sex after you inject opium, and they injected both the women and themselves” (The Korean Council and the Research Association on the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery 1999, 134)

This is clearly testimony about the soldiers’ perspective when they injected opium into the “comfort” woman. To read this as evidence that “comfort” women used opium in order to enjoy sex with soldiers must come from the author’s fantastic desire to see the comfort stations as idyllic. That she has not heard directly from the victims cannot be an excuse. For those of us who have listened to their testimonies and seen their deeply troubled faces as they told us their stories, it is an appalling interpretation.

Recently I had the chance to interview a woman who is still not able to put words to her experience. The comfort station she was sent to had three rooms and three other “comfort” women. There were three women assigned to the station during weekdays, but four during the weekends. I asked, “even though there were only three rooms?” “That’s why everyone could see what was going on,” she said, her face twisting with pain. Because she was the youngest, she was assigned to the shared room where there was no divider and another woman was also forced to deal with soldiers. Imagining this scene made me speechless.

The only time when she broke into a smile was when she talked about mochitsuki, the New Year’s rice-cake-pounding event. The rice cake was so delicious — it was out of this world, she said. I could not help but thinking about the hellish days hidden behind her smile as she talked about the only pleasurable memory in her life as a “comfort woman” that lasted several years. She would never be able to edit her memory so that only the fun part, the rice cakes, remained.

|

Yang Ching Ja. Photo provided by author. |

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Ms. Song Sin-do’s Testimony

Let me give the example of Song Sin-do whom I have been supporting.8 Whenever I asked her about the first time she was raped by a soldier, Ms. Song always dodged the question and never talked to me about it. While she avoided talking about her first three of seven years as a “comfort” woman in China, Ms. Song proudly talked about how she protected her body during her last four years. We kept analyzing the meaning of her words and actions in the process of our support for her court battle. Yet, many things remained beyond our understanding, despite our efforts. It was in this struggle to understand her that I first came across Judith L. Herman’s Trauma and Recovery: the Aftermath of Violence – from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (1992. New York: Basic Books).9

|

Trailer of Ore no kokoro wa maketenai (My heart is never defeated), a documentary film featuring Song Sin-do. |

Herman suggested that, according to current diagnostic criteria, it was impossible to treat the prolonged trauma experienced by victims who had long been confined and we should establish a new diagnosis called “complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” (119). When I read this, I felt that I finally understood some of the behavior exhibited by Ms. Song.

As she was telling me stories like one about a woman who drank cresol solution and killed herself, and another who committed double suicide with a soldier, Ms. Song said, “I could deal with anything but dying.” I think she killed her feeling of hating her life as a comfort woman in order to survive the comfort station. That’s why she cannot recall her first three years, especially the first rape which she has never talked about. By sealing the memory of her first three years, she was able to survive the comfort station. It shows that in the beginning when she was deceived and taken to the station Ms. Song desperately hated being forced to be a “comfort woman” like the other women who killed themselves. Nevertheless, Ms. Song chose to live. The feelings and memories that she had to smother in order to survive must have influenced her personality thereafter.

Herman says that a victim who is confined for a long time can learn about and recognize the outside world only through her captor:

“As the victim is isolated, she becomes increasingly dependent on the perpetrator, not only for survival and basic bodily needs but also for information and even for emotional sustenance. The more frightened she is, the more she is tempted to cling to the one relationship that is permitted: the relationship with the perpetrator. In the absence of any other human connection, she will try to find the humanity in her captor. Inevitably, in the absence of any other point of view, the victim will come to see the world through the eyes of the perpetrator” (81).

Reading this book, I felt that I finally understood the story of Ms. Song, who had clung to life while on the battlefield by suppressing her feelings. A Japanese soldier invited her to come to Japan with him, but then abandoned her as soon as they arrived. It was at that point that she tried to throw herself from a train to end her life.

The harm experienced by people like Ms. Song, who struggled to survive the “comfort station,” is extremely complex. To understand their experience, we need to have humility. By that I mean that those who have had only ordinary experiences can’t really understand, however much we use our imagination. I cannot find such humility in Ms. Park.

First Admit We Cannot Understand the Victims

I wrote on this topic in Ore no kokoro wa maketenai (My heart is never defeated).10 What I wrote then is still true today:

“I learned that the darkness experienced by women whose humanity has been victimized by the state is unintelligible to those of us who have only had ordinary experiences. Our movement started with ‘knowing’ what is ‘impossible to know.’ While recognizing the depth of a darkness that is ‘impossible to know,’ I promised myself that I would always make an effort to try to know, to respect Ms. Song’s will, and never allow myself or others to take advantage of her for the sake of the movement” (62-63).

|

Zainichi no ianfusaiban o sasaerukai ed. Ore no kokoro wa maketenai: Zainichi chosenjin “ianfu” So Shinto no tatakai [My heart is never defeated: zainichi Korean “comfort woman” Song Sin-do’s struggle |

Must Victims Compromise For There To Be “Reconciliation”?

It seems that there is a growing view in Japan, particularly among those who want to resolve the “comfort women” issue, that the movement led by The Korean Council and others “suppresses the memory” of victims and that this makes it even more difficult to resolve the issue. Ms. Park’s book seems to provide authoritative backing for the idea that reconciliation is only possible when the victims also compromise. I have shown, however, that we cannot solve the issue with this way of thinking.

This article is an expanded and revised version of my report on, and conversations with, participants in a panel discussion: “Can Perpetrators Talk about ‘Reconciliation’?” at Seventy Years After the War: East Asia Forum held at Japan Education Center in Tokyo on August 14, 2015. The original essay is “Higaisha no koe ni mimi o katamuketeiruka?: Park Yuha Teikoku no ianfu hihan.” Q&A Chōsenjin “ianfu” to shokuminchi shihai: anata no gimon ni kotaemasu.

Related Articles

Kitahara Minori and Kim Puja, The Flawed Japan-ROK Attempt to Resolve the Controversy Over Wartime Sexual Slavery and the Case of Park Yuha

Maeda Akira, The South Korean Controversy Over the Comfort Women, Justice and Academic Freedom: The Case of Park Yuha

Gavan McCormack, Striving for “Normalization” – Korea-Japan Civic Cooperation and the Attempt to Resolve the “Comfort Women” problem「正常化」を求めて 韓日市民協力と「慰安婦」問題解決への模索

Katharine McGregor, Transnational and Japanese Activism on Behalf of Indonesian and Dutch Victims of Enforced Military Prostitution During World War II

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, You Don’t Want to Know About the Girls? The “Comfort Women”, the Japanese Military and Allied Forces in the Asia-Pacific War

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Addressing Japan’s “Comfort Women” Issue From an Academic Standpoint 日本の「慰安婦」問題に学術的観点から対処するとは

Jonson N. Porteux, Reactive Nationalism and its Effect on South Korea’s Public Policy and Foreign Affairs

Jordan Sand, A Year of Memory Politics in East Asia: Looking Back on the “Open Letter in Support of Historians in Japan”

Wada Haruki, The Comfort Women, the Asian Women’s Fund and the Digital Museum

Notes

The original essay is “Higaisha no koe ni mimi o katamuketeiruka?: Park Yuha Teikoku no ianfu hihan.” Q and A Nihongun “ianfu” to shokuminchi shihai: anata no gimon ni kotaemasu, edited by Nihongun “ianfu” mondai web site seisaku iinkai. 2015. Tokyo: Ochanomizu shobo. 56-61.

Comfort Women of the Empire uses five of six volumes of testimonies collected and edited by The Korean Council and the Research Association on the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery. Hangukjeongsindaemunjedaechaekhyeobuihoe and Jeongsindaeyeonguhoe. 1993. Jeungeonjip 1 gangjero kkeullyeogan joseonin gunwianbudeul [Testimony collection 1: Korean military comfort women who were forcibly drafted]. Seoul: Hanul; Hangukjeongsindaemunjedaechaekhyeobuihoe and Jeongsindaeyeonguhoe. 1997. Jeungeonjip gangjero kkeullyeogan joseonin gunwianbudeul 2 [Testimony collection 2: Korean military comfort women who were forcibly drafted]. Seoul: Hanul; Hangukjeongsindaemunjedaechaekhyeobuihoe and Jeongsindaeyeonguhoe. 1999. Jeungeonjip gangjero kkeullyeogan joseonin gunwianbudeul 3 [Testimony collection 3: Korean military comfort women who were forcibly drafted]. Seoul: Hanul; Hangukjeongsindaemunjedaechaekhyeobuihoe. 2001. Gieogeuro dasi sseuneun yeoksa [A history rewritten through memory]. Seoul: Pulbit Publications; Hangukjeongsindaemunjedaechaekhyeobuihoe 2000nyeon ilbongun seongnoye jeonbeom yeoseonggukjebeopjeong hangugwiwonhoe. Hangukjeongsindaeyeonguso [A history rewritten through memory]. 2001. Gangjero kkeullyeogan joseonin gunwianbudeul 5 [Testimony collection 5: Korean military comfort women who were forcibly drafted]. Seoul: Hanul; Hangukjeongsindaemunjedaechaekhyeobuihoe buseol jeonjaenggwayeoseongingwonsenteo yeongutim. 2004. Ilbongun’wianbu’ jeungeonjip 6 yeoksareul mandeuneun iyagi [Testimonies 6: Japanese military “comfort women” A story that writes a history]. Seoul: Yeoseonggwa ingwo.

The first volume has been translated into Japanese (Shogen: kyosei renko sareta chosenjin gunianfu tachi. 1993. Tokyo: Akashi shoten). A partial translation of the collection in English is The Korean Council and the Research Association on the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery.1995. True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women: Testimonies, edited by Keith Howard and translated by Young Joo Lee. London: Cassell.

Herstory (2011) is an animated film directed by Kim Jung-gi about Ms. Chung Seo-Woon (1924-2004), who was coerced into becoming a “comfort” woman in Indonesia. The film uses the voice from her interview. In Japan, the film was translated by The Korean Council, published as Nihongun “ianfu” higaisha shojo no monogatari DVD tsuki ehon [A Japanese military “comfort” woman—a story of a girl victim; picture book with DVD], (Tokyo: Nihon kikanshi shuppansentaa, 2014).

Park mentions Herstory as an example of a literary and visual work that has propagated the image of Korean comfort women as constructed by The Korean Council. She begins her second chapter, “Struggle over memories: Korean stories” (147-161), by stating, “The image of comfort women that has been promulgated by The Korean Council has been reproduced through novels, manga, theater and songs in Korea. Now it is these severe and cruel ‘memories of comfort women’ that have been reproduced over two decades that dominate our collective memory in Korea” (147).

In June, 2014, nine former “comfort women” who live in the House of Sharing filed a petition charging Park Yuha’s Comfort Women of the Empire with defamation and calling for an injunction against publication. In February, the Seoul Eastern District Court upheld the charge of defamation and banned the book from publication unless thirty-four sections were removed.

Park Yuha. 2013. Jegugui wianbu – sigminjijibaewa gieogui tujaeng [Comfort women of the empire]. Seoul: Ppuriwaipari.

Established in 1992 by Buddhist and other support groups in Korea, The House of Sharing is a group home for former Japanese military “comfort” women. In 1998, it opened The Museum of Sexual Slavery by Japanese Military on its premises. The museum exhibits paintings and other artwork by halmonis or grandmothers that tell their history and memories.

In 1938 when she was sixteen years old, Ms. Song was tricked and taken to Wuhan, China, where she was forced to become a “comfort woman.” After Japan was defeated, a Japanese soldier took her to Japan. In 1993, she filed suit for “apology and compensation” against the Japanese government.

Herman, Judith L. 1996. Shinteki gaisho to kaifuku, translated by Nakai Hisao. Tokyo: Misuzu shobo.

Zainichi no ianfusaiban o sasaerukai ed. Ore no kokoro wa maketenai: Zainichi chosenji “ianfu” So Shinto no tatakai [My heart is never defeated: zainichi Korean “comfort woman” Song Sin-do’s struggle], Tokyo: Kinohanasha, 2007. The documentary with the same title was made in 2007 and directed by Ahn Hae-ryong.