Introduction

To many, the 2015 Japan-South Korea agreement to finally settle the Korean “comfort women” issue came as a surprise. For over two decades Japan’s wartime military sexual slavery remained the single most contentious issue dividing Japan and South Korea, severely affecting the bilateral relations and even becoming a concern for the US, which saw the tension between two of its allies in the Asia Pacific as troublesome. The 2015 comfort women agreement has promised that, with Japan’s one billion yen funding to assist the survivors together with a sincere apology, the “comfort women” issue will be “finally and irrevocably” resolved. While some media hailed this as a landmark resolution and an opening of a new, more positive era for Japan-Korea relations, it has also provoked a deep sense of dissatisfaction and anger among “comfort women” advocacy groups, feminists and the former Korean “comfort women” themselves. It seems clear that the state-state “agreement” (made without any consultation with the survivors) will not restore “dignity and honour” to the victims. After all, one of the origins of current antagonisms surrounding the “comfort women” issue is another state-state deal, the 1965 Japan-ROK Basic Relations Treaty, which failed to address the “comfort women” and closed the door on individual redress claims. The recent agreement is not the end of the “comfort women” issue – especially for the survivors.

|

|

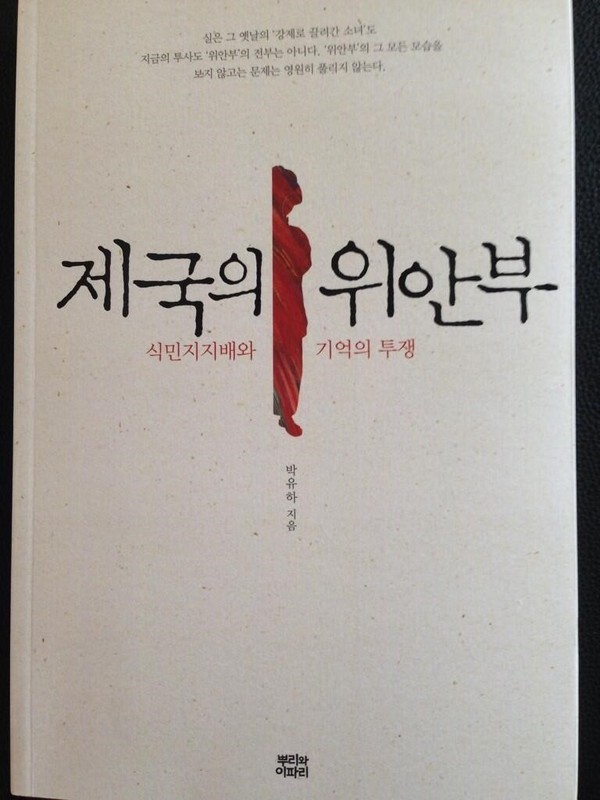

| Park Yuha and the Korean edition of her book | |

The two pieces below, translated from Japanese, address a controversy surrounding Park Yuha’s book, Comfort Women of the Empire (2013). Park is an academic at Sejong University with a PhD from Waseda University, Tokyo, and has written on Japanese literature, colonial literature and Japan-Korea relations (Her 2008 publication with Asia-Pacific Journal, “Victims of Japanese Imperial Discourse: Korean Literature under Colonial Rule” is available here). In 2014, following the publication of Comfort Women of the Empire, Park was sued for defamation against nine former Korean “comfort women”. In January 2016, after the first trial, a South Korean court ordered her to pay compensation to the nine former “comfort women” for the emotional distress that the book inflicted on them. Revision of the passages that were deemed defamatory was ordered. This was followed by another court order in February that her salary would be partially seized until she pays the required compensation.

The controversy focused on the book’s interpretation of the Korean “comfort women” system. It states, for example, that there is no evidence of a government policy of forcible recruitment, that the majority of the Korean “comfort women” were not teenage girls but in their 20s and 30, and that there were cases of romance between Korean “comfort women” and Japanese soldiers. Critics found descriptions of some of the relationships between “comfort women” and Japanese soldiers as “comrade-like” particularly problematic. Because of such a view, Park Yuha has been vilified in South Korea as an apologist for the Japanese colonial state, while some Korean academics have expressed support for her on the grounds that academic freedom is threatened.

In Japan (the Japanese edition was published in 2014), her book has generally been received positively and sympathetically and has also won two awards. The overall tone of Japanese mass media and reviewers has been that Comfort Women of the Empire is a courageous work that challenges the dominant narrative in Korea on the “comfort women” as pure victims by offering a more nuanced and complex understanding. In this view, Park’s indictment is an infringement on the freedom of scholarship. For example, see a statement issued by 57 Japanese and US scholars in support of Park and Maeda Akira, “The South Korean Controversy Over the Comfort Women, Justice and Academic Freedom,” translated and introduced by Caroline Norma. The two translated Japanese texts below challenge the understanding of Park as a victim-hero.

|

|

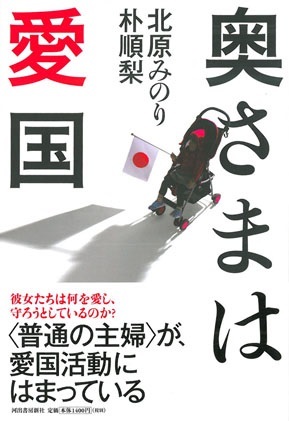

| Kitahara Minori and her book | |

The first piece is a Facebook post by Kitahara Minori, a feminist writer, activist and co-author of Okusama wa aikoku (patriotic housewives). This is a report of an event held in January 2016 with a visiting Korean former “comfort women”. It includes the text of a speech by Ms Ahn, the manager of the House of Nanum (a group home where several former Korean “comfort women” – halmonis – live. The nine plaintiffs in the lawsuits against Park Yu-ha are all residents). Ms Ahn was directly involved in the lawsuits over Park Yuha’s book, and here she explains in some detail the sequence of events that led to the charges and court decision. Professor Park has since responded to this Facebook post by Kitahara and rebutted Ms. Ahn.

The second piece is by Kim Puja, a Professor at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Kim warns that Japanese “liberal” intellectuals have been blinded to the “new” revisionism of Park Yuha, and explains why she sees Comfort Women of the Empire as a problematic work. She refutes Park’s argument that the young girls were a minority and the exception among Korean “comfort women”, emphasizing that Park erases the structural relationship between colonisers and colonised by (almost) equating Japanese and Korean “comfort women”. Kim insists that we need to keep our eyes on the “system” based on gender and racial discrimination and not be distracted by occasional personal relationships. Referring to the comment by Hata Ikuhiko (a major figure in historical revisionism in Japan) that Park has a similar view to his own, Kim warns Japanese “liberal” intellectuals who ‘lionise’ Park that their stance is contradictory.

The Korean court cases over Comfort Women of the Empire are ongoing, and the two texts provided here in translation are part of the long-standing debate over the continuing “comfort women” issue. One thing is clear in this complex discourse: Despite the Japan-Korea agreement the intensely politicised “comfort women” issue is not going to be “finally and irrevocaby resolved” any time soon.

Kitahara Minori’s Facebook post, 26 January, 2016

A brief report of “2016 Welcoming Halmonis from the House of Nanum: What We Want to Communicate Now” held at the House of Representatives Hall.

89 year old Kang Il-chul halmoni and 90 year old Yi Ok-seon halmoni came. First, Ahn Shin-kwon, the manager of the House of Nanum talked about how she learned of the “agreement” at the end of last year while watching television with halmonis. During her talk, Kang Il-chul halmoni, who was seated in the front row, cried out “we didn’t know” in a loud voice that rang out through the room large enough to hold 300 people. Her anger is not yet healed. It is unbearable to see that these people are still made to suffer this much.

After that, two halmonis spoke. Yi Ok-seon halmoni said, “The comfort station was an execution site to kill people as if they were pigs or cows”. She talked about how the women there were made to deal with 40 to 50 men per day and were hit if they resisted. Some of them died as a result. Yi Ok-seon halmoni showed us her scar that still remains on her head – “this wound was inflicted because I resisted”. In a loud, clear voice that would not have needed a microphone she expressed her anger. “I am a human being. Although I am a human being I was taken by Japan. (But Japan) has not resolved this issue. Why do I need to come to a place like this? I am really angry.”

The “Japan-Korea agreement” made at the end of last year was welcomed by major media as if it marked the beginning of a new relationship between the two countries. It was as though the ‘comfort women’ issue had been a burden for the Japan-Korea relationship and there was now a sense of relief that we are finally liberated from this burden. This optimism, I felt, revealed the insensitivity of Japanese society towards victims of sexual violence. But behind such reporting there are women who cried out with anger and frustration; and Korean civil society is beginning to push for the ‘retraction of the agreement’ – Japanese society needs to face these facts. Indeed, now is the time for Korean and Japanese citizens to connect with each other in opposition to Abe and Park Geun-hye.

Lastly, Ms. Ahn explained the sequence of events involved in suing Professor Park Yuha, author of Comfort Women of the Empire. Since her explanation aides understanding of the circumstances of the legal challenge to the book Comfort Women of the Empire, I have transcribed the content (translated by Yang Ching-ja) below. It is a little long but I’d appreciate if you would read it.

[transcribed text]

Around December 2013 I received a phone call from Professor Yu-ha. She said that we should raise a voice in opposition to the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan; so I said I am working with the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan to restore the human rights of the victims; why do you say such a thing to me? Professor Park next said, “there is something I would like to tell you urgently so please come to Sejong University.” Professor Park works there and it was inconvenient for me so I asked her to come to the House of Nanum. And one day with no prior contact or seeking permission, she came. She was not alone but was accompanied by NHK staff. I asked why she brought NHK along, and she said that they wanted to film a scene of Professor Park meeting the halmonis. I said if that was the case she should have contacted us in advance. The NHK journalist said, “we would like to film a scene in which Professor Park is doing some volunteer activities at the House of Nanum.” I said ‘how can you film such as scene, when Professor Park has never done volunteer activity?” and I did not let them film on that day.

Because of these events I read Comfort Women of Empire, twice. I think it was published in Korea in July 2013. At that time I had thought there was no need read this book. Its title was Comfort Women of Empire and not Victims of the Empire; so I thought this is a book that insults the halmonis and therefore was not going to read it. But (because of the above incident) in order to protest I had to read Professor Park Yuha’s book; so I read it twice.

When I read the book, I saw that Professor Park cited from the six-volume testimonies (by over 100 former comfort women); but I felt her book was totally different from the impression I got from the compiled testimonies I had read. But since my reading was from the perspective of a regular supporter of halmonis, I thought it would be better to have it read it by a third party; so I gave the book to Associate Professor Park Sun-ah, who teaches at a law school and asked her to read it. Seven students of the Law School then analysed the book and extracted over 100 highly problematic elements.

Then we read this book to halmonis. Halmonis cannot read books on their own, so we read the book for them many, many times. Once the book was read to them, halmonis said: “Why does the book say we were prostitutes, even though we were victims?” “What does it mean that we provided mental and physical comfort to the Japanese military?” “We cannot understand why the book says that we were comrades, wives and collaborators of the Japanese military. This is a violation of human rights.”

Since the halmonis were so angry I thought I should not leave things there. Although some of the halmonis have families, there are not many people who can help with legal procedures, and lawsuits cost money, too; so it was decided to start a lawsuit with the help of the House of Nanum. Hanyang University Law School, where the aforementioned Park Sun-ah teaches, was to bear the cost of lawsuit.

At first we thought we would just apply for a provisional disposition to ban the publication. This is because in Korea, too, the freedom of expression in relation to publishing is strictly protected; so we were only going to seek a provisional disposition to ban the publication. Even if we wanted to sue for defamation, usually defamation does not lead to a criminal charge in Korea. But even after this, Professor Park lied about her relationship with the halmonis. As I listened to her lies I decided this is no good and that unless we take all possible legal steps we cannot stop Professor Park.

So we started three lawsuits simultaneously: first, a provisional injunction to ban the publication and a restraining order to stop her from contacting halmonis; second, a civil lawsuit for defaming halmonis, with a demand for compensation; and third, a criminal complaint for defamation. We started all of them on the 17th June 2014.

There have been four court hearings on the provisional injunction to ban the publication. Halmonis as plaintiffs were present at all four occasions, but Professor Park did not turn up even once, thus ignoring the victims. By the way, the court has not banned the sales of the book. However the course did rule that 34 sections in the book would harm the honour of halmonis and ordered that unless these were removed, the book could not be sold or publicised. Professor Park omitted the 34 sections in a way that made it obvious which sections were ordered to be removed, and published a new edition of the book. She even published a Japanese version while the court cases were still ongoing. The halmonis reacted with anger. They said that Japanese publication would have been possible after the court cases and that the publication during the ongoing lawsuits amounts to a disregard of the law.

In a criminal trial there is a procedure called simultaneous examination, where the defendant and the plaintiff question each other facing one on one. There were two occasions of this. Yu Hui-nam halmoni from the House of Nanum took the trouble to participate, but Professor Park declined. With a criminal case it usually takes about a month to decide whether chargea will be filed, but with this case the prosecutors took one and half months, before finally announcing on the 18th of November that she would be indicted without arrest – for the crime of circulating false facts.

In Japan, there are many people who think that Professor Park is a victim whose freedom of expression has been suppressed and that the prosecutor used state power to prosecute her. But it is not the case that the prosecutor acted independently; they investigated in response to the halmonis who lodged a criminal complaint, and this resulted in her indictment without arrest. So it is Professor Park Yu-ha herself who is being protected by the law.

(Recently) a ruling was made in the civil case in favor of the plaintiffs. The court ordered her to pay 10 million won [US$8,262] to each plaintiff – though we demanded 30 million won. This ruling contained a word that is not part of legal terminology. The judge said: ‘having seen all evidence, what Professor Park has written is a shock.’ The word ‘shock’ is not a usual legal term, and I think with this word the judge expressed the appalling extent of this violation of human rights.

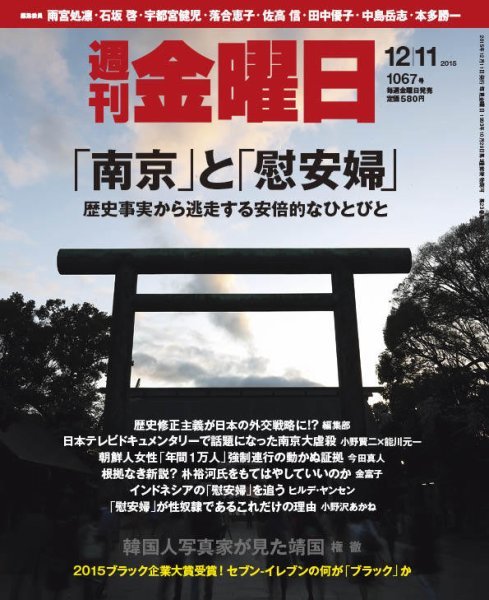

Kim Puja, “New Theory without a Basis? Should We be Lionising Park Yuha?”

From Shukan Kinyobi 2015.12.11 (no. 1067)

|

|

| Kim Puja and the issue of Shukan Kinyobi featuring her article | |

A Move towards Historical Revisionism in a New Guise

|

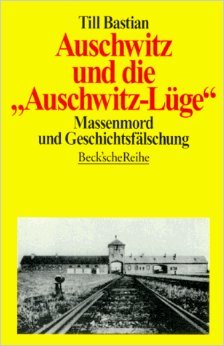

There is a book by Till Bastian, called Auschwitz and the Auschwitz-Lies. It succinctly summarises the fact of Nazi massacres as well as attempts to falsify history to sanitise and deny the massacres. In Europe, those who falsify history in this way are called “revisionists”; at the centre of their argument is an attempt to minimise the number of victims to erode the credibility of ‘mass massacre’. Sometimes they even create ‘evidence.’

Revisionist History as a Diplomatic Strategy

In Japan, too, “revisionists” have extended their influence since the late 1990s. Japanese revisionism is characterised by the denial of the “Nanjing Massacre” and the “comfort women” and has been led by the government and politicians. In October 2015, China nominated and UNESCO accepted the “Documents of Nanjing Massacre” into UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register. In response, the Japanese government threatened to re-consider Japanese funding for UNESCO. On this occasion, too, the number of victims became an issue; and attempts were made to discredit the claims of “massacre”.

What about the case of “comfort women” denial? Asahi Shimbun‘s special coverage of the “comfort women” issue that was published in August 2014 prompted Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s statement in the Diet in October of the same year that “the unfounded slander that the whole Japanese nation made them into sex slaves is going around the world today”. In September of the same year, the LDP’s Committee on International Communication adopted a resolution: “the fact of ‘forced coercion’ and sexual abuse of the comfort women has been denied”; “In all diplomatic settings, starting with the United Nations, and in international communication at both official and citizens’ levels, we will continue to assert our legitimate claim as a nation.” Revisionism has become the government’s and LDP’s diplomatic strategy.

The move towards historical revisionism is not limited to the government. A recent trend is revisionism “in a new guise”. One example is the book Comfort Women of the Empire (published in Korea in 2013 and in Japan 2014), authored by Park Yuha, a Korean scholar of Japanese literature. This book did not attract much attention in Korea at first, but it attracted sudden, widespread attention in June 2015, when nine victimised women from the House of Nanum sued Park for defamation (civil and criminal) because of the book’s description [of the “comfort women”] as being in a “comrade-like relationship” with Japanese soldiers, that is, suggesting that they were “collaborators”.

On the other hand, if we turn our eyes to Japan we see that a “liberal” newspaper Asahi Shimbun, other media and some Japanese (male) intellectuals are “lionising” Park’s discourse (for a detailed criticism of the book, see blog by Meiji Gakuin University Associate Professor Chong Yong-hwan).

So what is new and not so new about Park’s book?

Young Girls were “Minority and Exceptions”?

First, let’s look at Professor Park’s argument that Korean girls who were made into “comfort women” were a “minority and exceptions”. This is a new argument.

In her book Professor Park 1) uses the testimony of a victimised woman taken from a compilation of testimonies edited by The Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by the Japan and Chongsindae Research Association (Military Comfort women Who were Forcibly Taken Vol. 5; hereafter ‘Force 5′; in Korean) and introduces a statement that “I was the youngest. Everyone else was older than 20”; and 2) regarding the the 20 Korean “comfort women” who were captured in Myitkyina, Burma, and interrogated by the US Office of War Information, write that their “average age was 25”. Her book thus emphasises that young girls who became Korean “comfort women” were “a minority and exceptions” and furthermore insists that what made them into “comfort women” was “the will of private brokers, rather than military will”.

Regarding the first point, however, if we actually look at volume 5 of the compiled testimonies, Force 5, the age of those who testified at the time of the drafting was all “under 20”.

Also, with the second case of the 20 Korean “comfort women” in Myitkyina, when they were captured their age was “23 on average”. At the time of their drafting two years prior to the capture, their age was “21 on average”, with 12 out of the 20 women being minors (international law considers a 20 years old a minor), which makes them majority.

Therefore Professor Park’s new argument that “young girls were minority and exceptions” is fabricated “evidence”, and lacks foundation (See Fight for Justice Booklet 3 Chosenjin Ianhu to shokuminshihai sekinin, Ochanomizu Shobō).

Background: Colonial Rule and Discrimination

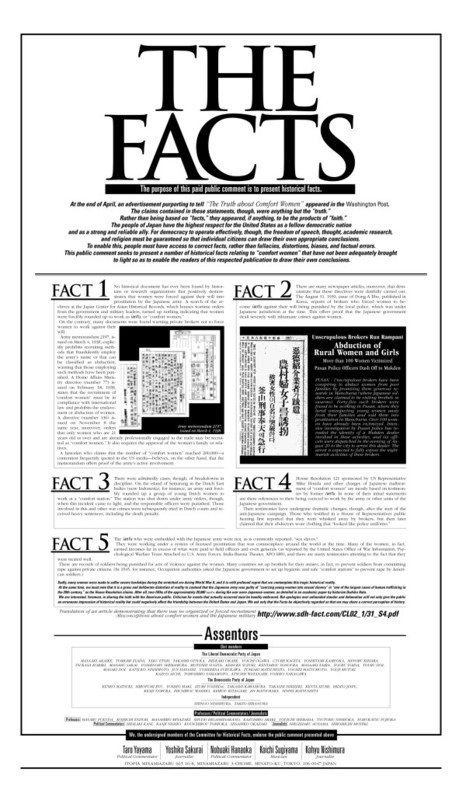

Next, the ‘denial of sexual slavery’. Not only Professor Park but others such as Professor Hata Ikuhiko, “THE FACTS” (Washington Post opinion ad) and Prime Minister Abe have also put forward such a view.

|

What characterises Professor Park is her points such as that Korean “comfort women” were not minors, that they played some patriotic role or that there existed some romantic relationships with soldiers; in this way she emphasises the relationship between Japanese soldiers and Korean “comfort women” in comfort stations as a “comrade-like relationship as fellow Japanese”.

Why? It seems that this was done in order to create a new image of Korean “comfort women” as the “comfort women of the Empire”, who share the same characteristics as the Japanese “comfort women” and therefore almost identical to the Japanese “comfort women”. In this way the relationship between the ruler and the ruled thus disappears; but the premise here is an understanding that Japanese ‘comfort women’ who had previously been licenced prostitutes were not sex slaves.

Exposed here is a lack of understanding of the Japanese “comfort women”. The Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery held in 2000 and recently published Nihonjin Ianfu (Japanese comfort women) edited by VAWW RAC [Violence Against Women in War Research Action Centre] have clarified that Japanese “comfort women” were sex slaves both under the licenced prostitution system and in the comfort stations. Emotional exchanges or romance are irrelevant. The central issue is not occasional personal relationships but the system itself.

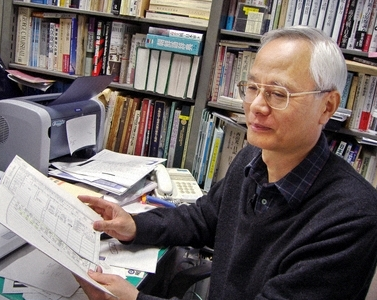

There were policy-related reasons for the large number of young girls among Korean “comfort women”. First of all, as Professor Yoshimi Yoshiaki has revealed in his book Jūgun Ianhu (Military comfort women; 1995 Iwanami Shoten), the Japanese government’s drafting of the ‘comfort women’ was based on racial discrimination. Drafting of Japanese women were limited to “female prostitutes who are at least 21 years old and have no venereal disease” (Memorandum issued by the Director of the Police Bureau of the Home Ministry, 23 February, 1938); From the colonies, those who were ‘underage, non-prostitutes and with no venereal disease” were drafted. Secondly, colonies were used as a loophole, exempt from international laws such as TheInternational Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children. Thirdly, in order to counter venereal disease among soldiers of the Japanese military, unmarried virgins from colonies became target (for example, see a memorandum by the military physician, Dr. Aso Tetsuo).

|

|

| Yoshimi Yoshiaki and his book | |

That is, the drafting was affected not by the will of “private brokers” that Dr Park talks about but by “the will of the military and government”. Of course, the largest reason for targeting underage Korean women was Japanese colonisation of Korea and racial/sexual discrimination.

Professor Hata’s Endorsement

Interestingly, Professor Hata Ikuhiko (a major figure in Japanese historical revisionism) evaluates Professor Park highly. Professor Hata, who locates the “comfort women” system as a “war-front version of the licenced prostitution”, writes of Professor Park as follows (“Ianfu: Jijitsu o misueru tame ni (The comfort women: in order to face the facts squarely)”, Shūkan Bunshun 2015 May 7.14; I’d like to thank Associate Professor Chong Yong-hwan for pointing out this article to me):

“Professor Park Yuha of Sejong University in Korea presents a similar understanding to mine [Mr Hata’s]. However, since she rejected the forcible drafting and sex slave view and pointed out that ‘it is hypocritical to ignore the existence of comfort women for the Korean military and US military in Korea’, she has been sued by a comfort women advocacy group for being ‘pro-Japan'”.

|

|

| Hata Ikuhiko and the issue of Shukan Bunshun with his article | |

Mr Hata understands that Professor Park has “rejected the forcible drafting and sex slave view” and endorsed this as a ‘similar understanding” to his own. (Incidentally, Professor Park was sued by nine victimised women living at the House of Nanum; also, the aforementioned Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery supports the victims of the “comfort women” system of Korean military and US military in Korea. So there are some misunderstandings here).

Professor Park’s understanding of the “comfort women”, though seemingly new, is therefore ultimately revisionist. Her denial of military involvement and use of force in recruitment and at the comfort stations will ultimately damage the Kono Statement. But needless to say, the most problematic of all is the Japanese “liberals” who, despite their distance from Professor Hata’s understanding of the “comfort women” and their support of the Kono Statement, lionise Professor Park who has a “similar understanding” to that of Professor Hata.

Recommended citation, Kitahara Minori and Kim Puja, Introduction and translation by Rumi Sakamoto,”The Flawed Japan-ROK Attempt to Resolve the Controversy Over Wartime Sexual Slavery and the Case of Park Yuha”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 5, No. 2, March 1, 2016.

Related articles

- Maeda Akira, translation and introduction by Caroline Norma, The South Korean Controversy Over the Comfort Women, Justice and Academic Freedom: The Case of Park Yuha

- Norma Field, Tomomi Yamaguchi, The Impact of “Comfort Woman” Revisionism on the Academy, the Press, and the Individual: Symposium on the U.S. Tour of Uemura Takashi

- Mark Auslander and Chong Eun Ahn, Responding to the “Comfort Woman” Denial at Central Washington University

- Emi Koyama, The U.S. as “Major Battleground” for “Comfort Woman” Issue

- Gavan McCormack,Striving for Normalization: Japan-Korea Civic Cooperation and the Attempt to Resolve the “Comfort Women” Problem

- Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “You Don’t Want to Know about the Girls?”: The “Comfort Women,” the Japanese Military and Allied Forces in the Asia-Pacific War

- Nishino Rumiko and Nogawa Motokazu. The Japanese State’s New Assault on the Victims of Wartime Sexual Slavery

- Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Reexamining the “Comfort Women” Issue