Ikeda Hiroshi wrote an important opinion piece for the Tokyo Shimbun newspaper on February 26, 2016. Ikeda is a Kyoto University emeritus professor of German literature who has devoted his career to researching fascism. His numerous books include The Weimar Constitution and Hitler. Ikeda published this Tokyo Shimbun article at a tumultuous time in Japanese society: the government had shortly before pushed through state secrets and national security laws, and overridden the constitution to allow overseas military deployment. In response, mass rallies were staged outside the Diet building. In this climate, Ikeda’s article is an unusual example in the Japanese press of criticism of a reigning government through direct historical comparison with a fascist regime of another country. At the request of the Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Ikeda provided an original, expanded article on this theme. This article is particularly significant now that both houses of the Japanese Diet have two-thirds of their members supporting constitutional revision after the July 10 Upper House election, and Abe talks about starting debate this fall, with priority given to a emergency decree clause. CN

|

|

|

| Ikeda Hiroshi | The Weimar Constitution and Hitler |

Nazism as Fiction |

Midway through last year, Japan’s Abe Shinzo government ignored the opposition and alarm of public opinion to enact a set of laws called “national security-related laws.”

The peace provisions of Japan’s constitution contained in the Preamble and Article 9, stipulating no maintenance of armed forces and renunciation of war, had already been greatly diminished through the enactment of various laws. However, the laws enacted by the Abe government last year directly violate the constitution’s prohibition of the “use of force as means of settling international disputes,” and allows the Self-Defense Forces to use weapons to engage in acts of war overseas in the name of the “right to collective self-defense.” This decision contradicts the policy of Abe’s own party, the LDP, as its past administrations had consistently regarded such reinterpretation of the constitution “unacceptable.” With this decision, Japan now finds itself a country capable of going to war, without amending the constitution; thus breaching it.

This assault on Japan’s constitution by Abe’s LDP/Komeito coalition government is in many respects redolent of the historical precedence of Hitler’s assault on the Weimar Constitution. Of course, drawing parallels between contemporary and historical events must be undertaken with extreme caution: a fearmongering cry like “a wolf is coming!” or simplistically labelling Abe another Hitler distracts public attention from what is really happening and risks misguided responses to it. There are lessons we can nonetheless draw from history, and in fact must. We need to set aside demagoguery, and instead look back on history in a clinical way to learn its lessons and use them for appropriate decisions and actions.

Hitler came into office via a legitimate election during the Weimar Era

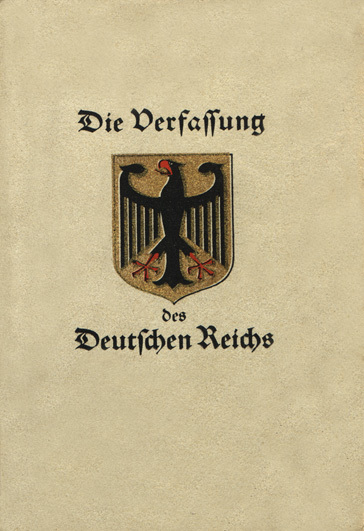

Today, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party he led are remembered only in negative terms, because they are remembered for their perpetration of the world’s most horrific atrocities, which include the suppression of political opponents, the Holocaust against Jews and Roma, massacre of social minorities such as the disabled, those who suffered genetic diseases and those who evaded work, whom Nazis called “not worthy of living,” as well as for their aggressive war and killing of civilians. However, as is well known by now, Hitler and the Nazi Party did not come to power through coup or conspiracy. The party was simply voted number one in an official parliamentary election, and Hitler, as head of the party, was appointed prime minister by the president. In other words, he was chosen by the German constituency. Furthermore, this election was held under the Weimar Constitution, which is viewed even today as one of the most democratic constitutions in history. The Weimar Constitution contained human rights provisions inherited by the current Japanese constitution. It included protections such as freedom of thought and creed, freedom of speech and press, freedom of assembly and association, secrecy of communication, freedom of residence, and freedom from bondage (i.e., prohibition of arrest without a warrant).

We might be perplexed by the fact that Hitler’s dictatorship arose in the context of a constitution containing these kinds of provisions, but a careful examination of the transition from the Weimar Republic to Hitler’s Germany will make understandable why such a historical process was possible. This process in fact raises serious concern over the current Japanese political and social situation.

There were many political parties in the Weimar Republic, and each had its own stable constituency base. Over the fourteen years of the Republic, no single party had a parliamentary majority; not even the Socialdemocratic Party of Germany, which was the strongest party for a long period of time. This is vastly different from the situation in Japan where the LDP and its predecessors have held parliamentary majority for nearly all of the post-war period. The Nazi party started out as a regional political party, and swiftly expanded its support base. Soon it became Germany’s largest party, and seized the reins of power. But it still never held a parliamentary majority. When Hitler came to power on 30 January 1933, it had only one third of total votes and the same ratio of seats. This was why Hitler was only able to secure two Nazi Party members in the 12-person cabinet other than himself. But Hitler dissolved the parliament two days after assuming power, and held a repeat-election on 5 March 1933. Nevertheless, even though Hitler’s control of the police force allowed him to significantly impede the electoral activities of opponents, the Nazi Party still achieved only 44 per cent of the vote, and 288 seats in a 647-seat parliament.

Notable is the fact this repeat-election result is similar to that recorded in the proportional representation district of Japan’s latest Lower House election in December 2014, in which the LDP/Komeito coalition received around 47 per cent of the total vote. National elections in Japan are decided on both single-seat and proportional representation districts. Proportional representation districts accurately reflect the voter party support, but the coalition’s win in many single-seat districts led to its overwhelming victory. In fact, Abe’s coalition government really has less than majority voter support (i.e. 47 per cent).

|

Abe securing prime ministership on 24 December 2014 |

In contrast to the Japanese electoral system in which the single-seat constituency system works overwhelmingly in favour of the ruling party, the German electoral system during the Weimar Era was one that eminently reflected the will of the people. It comprised nationwide proportional representation, where people voted for the party of their choice, and each party gained one seat for every 60,000 votes attained. Voter turnout for national elections was generally very high during the Weimar Era, ranging from around 75 to 90 per cent. The election on 5 March 1933 (effectively the last election held in the Weimar Republic) recorded a voter turnout of 88.7 per cent, and the 44 per cent of the votes that the Nazi Party gained, which gave them 288 representatives in the parliament, was an objective reflection of the will of the people. In other words, while the Nazi Party attracted the greatest number of votes of any party, they still did not attract the majority of cast votes. In spite of this, Hitler was nonetheless able to forge political dictatorship. We should keep this fact in mind when we reflect on the current Abe government

How did a highly democratic constitution produce the Hitler dictatorship?

|

|

| Weimar Constitution booklet | Hitler before Reichstag, 1933 |

A lesson we might learn from the election of both the Hitler and Abe governments is that even minority-elected parties can, once they are in power, implement a political program largely opposed by the population. Hitler’s Nazi Party and Abe’s LDP, for better or for worse, became leading parties in national elections, by gaining the most number of seats. But how did Hitler’s Nazi Party become the leading party? Who supported them?

The Nazi Party came to national prominence as a result of success in the national election of September 1930. In this election, the Nazi Party, which had previously held only 12 seats, suddenly gained 107 seats and became the second leading party in the parliament. This result was a product of the world economic crash that started in October 1929. Up until the crash, Germany had been slowly moving toward post-war reconstruction after the Great War, but the Great Depression brought that to a halt. Unemployment soared and societal instability spread. In this climate, the Nazi Party’s exhortation to “make Germany strong again” through Hitler’s strong, decisive and action-oriented leadership was a vote winner. In 1932, the year prior to the Nazi Party’s election, unemployment in Germany reached 44.4 per cent. In the July election, on the basis of campaign sloganeering to “eliminate unemployment,” the Nazi Party attracted 37.4 per cent of the vote, which made the party the largest in the parliament. The Party received less support in the subsequent election of November that year, dropping to 33.1 per cent of the vote, but still retained majority-party status, and so the president was forced to appoint Hitler, as the head of the Nazi Party, to the prime ministership of Germany on 30 January 1933.

So who voted for the Nazi Party? It was not unemployed voters. Their votes went to the Communist Party. It was actually employed voters who feared unemployment who voted for the Nazi Party. This fact is redolent of the strategy of the Abe government who came to power on the basis of campaigns targeting voters fearful of unemployment and uncertain about the future who responded to the party’s pre-emptive “Three Arrow” and “New Three Arrow” approaches to economic policy-making.

Hitler’s Nazi Party garnered votes through stoking fear among voters over straw-man enemies who were attacked as stealing local jobs and causing mass unemployment. On this basis, a combative and discriminatory mindset towards Jews spread among the population, and the path towards the Holocaust was laid. Jews in actual fact comprised just 0.9 per cent of the German population at the time, so attributing them responsibility for 44-per-cent unemployment rates was nonsensical. This kind of demagoguery is similarly seen in the tactics of the Abe administration in its demonising of Korea and China, which has generated a groundswell of xenophobic feeling towards foreign nationals in Japan. This has bubbled to the surface in the form of public abuse of resident Koreans in Japan. We find ourselves easily moved to hatred the harder our lives become and the more uncertain we become about our immediate future in Japan.

Rather than pointing out these intersections of comparison between the Abe and Hitler regimes, I believe there is more value in critically examining how we came to be led by these leaders. The German people in the Weimar Era, our predecessors in history, followed Hitler and allowed the Weimar Republic to give birth to Hitler’s dictatorship.

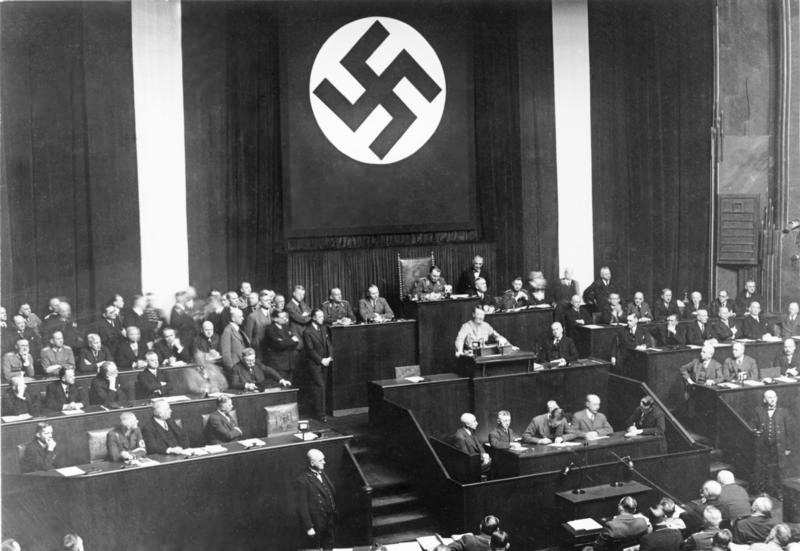

At the same time as rejecting the Weimar Constitution, Hitler was eager to amend it. However, he was unable to secure the two-thirds majority in parliament needed after the March 1933 repeat-election to succeed in this. Accordingly, he pushed through the new parliament a law, so-called “Enabling Act”. This law would deprive the parliament of lawmaking powers and grant them to the government. Not even post-hoc approval from the parliament was required. The prime minister’s assent was all that was required, and this was Hitler. Article 2 of the Enabling Act even allowed the government to enact laws that violated the constitution. With the enactment of the Enabling Act, the Weimar republic was destroyed and dictatorship under Hitler’s Nazi Party became legally the state of affairs.

Why did the parliament allow the Enabling Act to pass? Why did the Nazi Party gain more seats in the March 1933 election to stay as the leading party, even though constitutional overthrow by the Nazi Party was anticipated as its outcome? We need to consider two historical facts in order to answer these questions.

First, one political party played a critical role in the passage of this law. Under the Weimar Constitution, any bill that would require constitutional revision or amendment would require attendance of two-thirds of the parliament and two-thirds of votes among them. The Nazi Party did not have the numbers to make up two-thirds of the parliament even with support from its nearest right-wing supporting parties. This two-thirds majority was achieved, rather, because the Catholic-aligned German Central Party, which was part of the pro-constitution Weimar Coalition, chose to follow Hitler just before the voting on the bill, out of concern for their self-preservation. It broke a parliamentary boycott and voted in support of the Enabling Act. This historical scenario is perhaps reminiscent of conditions in Japan in the current day.

Once Hitler gained complete control over the legislature, he enacted a law banning the convening of any new political parties other than the Nazi Party and banned existing parties. The German Central Party, which sold out its principles and acted to secure its political power by following Hitler, was also dismantled.

|

National Security Law bill forcibly passed in Upper House, 17 September 2015 |

Here is another historical fact that would address the question of why the Nazi Party won the March election in the first place. Even before the enactment of the Enabling Act, Hitler had begun political manoeuvering for constitutional destruction. The Abe government’s forceful enactment of the National Security Laws in September 2015, as many commentators have observed, was an important step towards dismantling the Japanese constitution that was comparable to Hitler’s passing of the Enabling Act. However, for Hitler, the Enabling Act was not the only way to destroy the Weimar Constitution. Nor will it be for the Abe government to destroy the constitution only with the National Security Laws.

The Presidential Emergency Decree and the LDP’s proposed constitutional amendments

While the Weimar constitution is seen as one of the most democratic in the world, it nonetheless contained Article 48, which allowed exceptional powers to be awarded to the president, called “presidential emergency decree.” Article 48 specified, “If public security and order are seriously disturbed or endangered within the German Reich, the President of the Reich may take measures necessary for their restoration, intervening if need be with the assistance of the armed forces.” In order to facilitate this power, the rights enshrined in the constitution could be temporarily suspended, either in whole or in part. Hitler and the Nazi Party, once they were in power, were able to forcefully intervene in the national parliamentary election by exercising this “emergency decree” on two occasions. The first presidential emergency decree that Hitler made President Hindenberg declare banned criticism of the government or the Nazi Party and strikes, and prohibited any associations or publications that opposed these measures. As a result, opposition party election campaigns were curtailed. The burning of the Reichstag that occurred a week before election day became the second pretence for declaration of emergency powers. This time it was declared that anyone plotting or abetting the murder of the president or officials of the government was to be either executed or imprisoned for life, or at least for 15 years. On the contrived basis that the arsonist was a communist, the Communist Party was banned and arrest warrants issued for all of its candidates in the national election. “Plotting” and “abetting” were obviously suspicions very easily manufactured by police and prosecutors. These two instances of emergency decrees cleared a path for the Enabling Act, and they were nothing but political violence that dealt a fatal blow to the Weimar Constitution.

The eagerness of the Abe government to amend the Japanese constitution is a fact not irrelevant to this history of past atrocities by Hitler and the Nazi Party. The constitution amendment drafted by the LDP in 2012 contained Articles 98 and 99 that permit the declaration of a state of emergency and related measures. Article 98 permits the prime minister “to declare a state of emergency, in accordance with law and with the approval of the cabinet, in cases where the country is under attack by external elements, internal order has broken down, large-scale natural disasters have occurred such as earthquakes, or other situations determined by law.” Once a state of emergency has been declared, Article 99 further allows the cabinet to, “in accordance with law, make directives that have the force of law, and the prime minister to make budgetary allocations to support them. Local government bodies can also be directed to carry them out.”

Hitler solicited public support at a time of mass unemployment and failure to achieve post-war reconstruction in Germany. He appealed to an idea of Germany as a proudly historic and cultured nation that had been punished for losing the Great War through the treaty of Versailles. Prime Minister Abe succeeds and reinforces the LDP’s long-standing claim that the Japanese constitution was forced upon the nation by the victors of war, and he makes it clear that he wants to see constitutional revision while in office. He broadcasts the view that emergency decrees are a natural part of any country’s constitution, but the Constitution of Japan shows to the world Japan’s determination to realize “peace without resorting to war” by stipulating unnatural (unusual) clauses. But the fact that Japan’s constitution does not have an emergency decree clause, which existed even in the Weimar Constitution and paved the way to Hitler’s dictatorship, is a reflection of the constitution’s fundamental principle of no maintenance of armed forces and its renunciation of war.

Who comprises the polity and society? — The meaning of Article 12 of Japan’s constitution

As Hitler seized the reins of political power and full lawmaking powers, he in fact resolved the horrendous problem of mass unemployment in just a few years. Hitler enjoyed only minority support from the German population when he took office, but his popularity increased markedly year by year. Even after the innumerable atrocities by the Nazis were revealed after Germany’s defeat, the majority of people in Germany who lived under Hitler’s regime reflected on that time as a golden age of stability and fulfilment. This was in spite of the fact that the period was one in which Germany’s minorities had both their freedoms and their lives stripped away.

German society in the immediate aftermath of war generally believed that the atrocities and the wartime invasions had been perpetrated by Hitler and the Nazi Party, and that the German people were rather victims of this fact. Either the population was kept in the dark, or it was deceived about these realities. This viewpoint is similar to the general one held by Japanese people still today that the Asia-Pacific War was perpetrated by a tripartite group of the military, business conglomerates, and nationalists.

There is some reason for German people to have continued to see the Nazi era as a golden age after the war. Hitler’s administration not only solved the employment problem, but it also created a society that was meaningful for many citizens. The Nazi Party created volunteer programs which were largely responsible for the decline in unemployment. The Nazi Party, inheriting the policies of the Weimar government, put the unemployed to work under the banner of self-directed labour service, and youth were encouraged to join. On this basis, many citizens came to feel that it was their duty to devote their voluntary efforts and their spirit of social contribution to Germany’s emergence from economic depression, and the German society as a whole developed a sense of pride in doing so. The volunteer labour service scheme did not itself reduce unemployment, but rather allowed the construction and primary industries to employ labour at exceptionally low wages (tips only), and to profit accordingly. On the basis of this profit acquired over time, these industries were eventually able to employ full-time workers. This process is essentially similar to the current situation in Japan where nominal unemployment rates have been declining as the companies retain earnings and increase temporary workers in the midst of widening poverty and inequality.

With a spirit of volunteerism permeating German society, the Hitler government in June 1935 legislated the “imperial labour service” (Reichsarbeitsdienst) system to replace voluntary labour service, making citizens between ages 18 and 25 become liable for six months of volunteer labour. The most notable among such construction projects in which workers received an allowance less than one fifteenth of the legal wage was the Autobahn.

Parallel to this, during the winter period when unemployed and impoverished families had the most difficulty surviving, the Hitler government established a “winter rescue scheme” of volunteerism under the sloganeering banner of “all citizens” supporting those in need. Germans independently mobilised to support the scheme through raising funds and donating goods. In addition, there were many other volunteer opportunities established in all aspects of German society for all citizens. This was how German citizens became the authors of major national infrastructure, and actors in their own society. Germany under the Nazis had a mirror outlook to what Abe now wants for Japan: a “one-hundred million all-active society [一億総活躍社会].” The establishment of the “imperial labour service law,” which stipulated labour service duties in replacement of voluntary labour service, came three months after the reinstatement of the draft and so the abandoning of the constraint of Treaty of Versailles.

I have described Hitler’s path because it should not be repeated in contemporary Japan. I do not mean to suggest that 1930s’ Germany is being replayed in Japan today, but, rather, to emphasise the fact that we are the ones responsible for not allowing it to be replayed. The German citizens of the Weimar Republic were unable to give effect to the Weimar Constitution in spite of its acknowledged democratic provisions. These citizens entrusted the politician Hitler with sole responsibility for getting the country out of crisis. When we Japanese citizens try to choose a different path from this, we must first look to our own constitution. Contemporary advocates of Japan’s constitution are wont to argue that the constitution fetters policymakers and people in power, and makes them, rather than the people, liable for their actions. However, Article 12 of Japan’s constitution says that the “freedoms and rights guaranteed to the people by this Constitution shall be maintained by the constant endeavour of the people.” The duty and responsibility to protect and realize our own freedoms and rights do not lie in policymakers and politicians, but in ourselves. Parliamentary democracy is not about entrusting all powers to elected members.

Hitler demanded from the German citizenry full powers through the Enabling Act, and forced it upon the citizenry. The LDP too, in its constitution revision bill, is attempting to mandate full transition of powers to the government on the pretext of “emergency situations.” We must not merely chant the maintenance of Japan’s post-war constitution. Rather, in order to overturn the current situation that is in breach of the constitution and enact the spirit of the constitution in real terms, we must become ourselves actors in our own political system and society. This alone, moreover, is not enough. The German people became actors in this way through volunteer activity, even while they were being used, manipulated and controlled. Their exuberance stopped them from seeing the minorities who were being concurrently bullied and killed. We, in contrast, can turn our minds to these social minority groups and see the things that the current government cannot see in its overwhelming majority power. We must see ourselves as having that kind of social agency. We may be small in numbers, but we have a particular duty to resist the arrogance and violence of the majority. Democratic society can realise its democratic nature only through the efforts of minority groups. The history of the progression of Hitler and the Nazis to become Germany’s ruling party teaches us this lesson now more than ever.