Part One: Growing Up in Wartime Tokyo

I was born in October 1936, and my first clear recollections are those of the Nishi-Ōkubo neighborhood of Tokyo around 1939. Akira and I lived with our grandparents in their big house set in by a granite gate.1 I knew that my parents were in Paris but never missed them. Diagonally across from our house to the left were the homes of Yoshinobu-chan, Chika-chan, and Mitchan. A street stretched perpendicular to our house. On the right was the Kibōsha (a nice-looking building used by Korean rights activists) and then the home of Yatchan. Yatchan’s older brother Sato-chan went to middle school. Yatchan’s younger brother Yotchan was not yet school age. On the left, across the street from Yatchan’s house, was the home of Sakudō Naoko-chan. She had a little brother nicknamed Kō-bō. Later, the Maebashis moved into the large house next to ours. They had three children: a fourth grader who might have been named Hidehiko, a girl my age called Reiko-chan, and a younger brother who was probably named Kunihiko. One day, my brother and I were in a second-floor room with a large desk. Hidehiko gave us a dictation test. Among other things, we had to write the characters for “bu-un chōkyū o inoru” (I pray for your good martial luck).

|

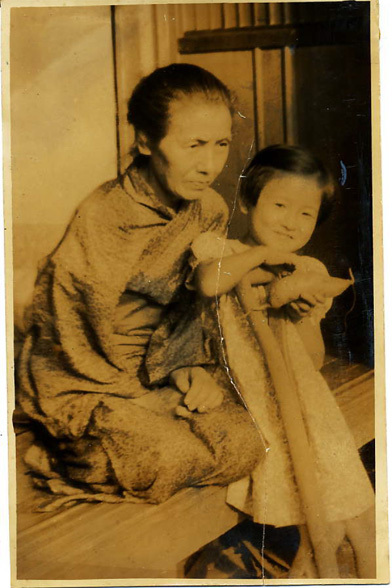

Kyoko and her grandmother Tsukamoto Man, 1940s. Photograph from the family’s personal collection. |

One day, our grandparents took us, I think, to Tokyo Station, to meet our parents. It was July 1941. A few nights before, Grandmother had said to me, “You’ll sleep in the same room [with me] when your mother is home. Is that okay?” I didn’t think much about it. When my parents appeared, I took an instant liking to them. I intuitively knew my father was a good person. He just smiled without saying a word. He looked wonderfully warm and genuine. My mother smiled gently. Grandmother prodded, “Why don’t you say okaerinasai (welcome home)?” I hid behind her kimono sleeve. My mother said, “It’s okay, isn’t it? (iiwayo, nee)?” It was a sweet thing for her to say.

The next thing I remember is my mother standing in a room with a wooden floor next to the parlor, letting Akira and me take turns jumping at her from a low window sill. Years later when I mentioned this to her, she said, “Of course, I was trying my best to win your hearts.” Her efforts were unnecessary because we quickly discovered where we belonged. When my brother ran into the house crying, having been barked at by a dog, Grandmother rushed to meet him. Heedless, he ran straight to his mother.

Grandmother had been rather strict, so it is no wonder we found comfort in Mother. But Mother proved to be stricter once she knew she had won her children’s hearts. She liked good manners, decent language, and honesty. Once after breakfast I found a little bowl of kinako (roasted soy flour) left on the small table (chabudai). Nobody was there. Mother was upstairs, probably airing out the futon. I looked around, made sure it was safe, and took a spoonful of kinako. It tasted so good that it was difficult to stop. I measured the time it would take to enjoy another spoonful. Nobody appeared. So I assumed it would be fine to spend that same amount of time eating another spoonful. I repeated this a few times until Mother came down from upstairs. She looked at me and asked, “Are you eating kinako?” Because she looked at me kindly, I made the big mistake of answering “No.”

Mother then reprimanded, “If you were enjoying kinako, fine, just say so. Why must you lie?” She caught hold of me and carried me to the veranda, saying she would not have a liar in the house. She was throwing me out to the yard, when Grandmother appeared.

“Naoko-san, you don’t really have to do that,” Grandmother admonished and tried to release me from Mother’s grip. This seemed to enrage Mother further, “I don’t want such a child; I must throw her out.” This was one of the very few times I cried. It was also the only time that I helped myself to food left on the table.

Mother did look seriously angry then, but later as I looked back on that day, I realized that she might merely have been carried away. Probably, she was fighting to establish rules for her children, who appeared to her to have been somewhat spoiled by their grandmother.

Apparently, I had not learned from that lesson. The summer I was five, I ran into our young milkman on the street, and he gave me a little ball of candy called kawaridama. As you tossed the kawaridama on your tongue, it melted and gradually revealed different colors. I was not sure if I should accept the candy, but he was such a familiar face and we affectionately called him “gyūnyūya no oniichan” (milk delivery big brother), so I trusted that it would be okay to do so. My mistake was that I didn’t bring the candy home to show Mother first. As I was coming home with the candy in my mouth, Mother happened to be walking toward me. I quickly wiped my mouth with the skirt of my dress. She stopped me and asked, “Are you eating candy?”

“No,” I replied, I think for no other reason than that her question seemed to warrant that answer. What would have happened if I had said “Yes”? But she didn’t like my answer.

“Then your teeth are bleeding,” Mother said, grabbing my arm. “Let’s go to the dentist.”

Not that Mother was always strict. When I was ill in my sixth calendar year (maybe almost five by the Western count), she gave me her blood. I was running a high fever, and I remember going to the hospital with her. I was dressed in kimono, as I always was when I was unwell. Kimono was believed to be warmer than Western clothing. After the blood transfusion at the doctor’s office, I felt stiff and heavy. I had, of course, intended to walk home, but Mother carried me on her back. I felt shy, overprotected, and uncomfortable by this sudden baby-like treatment. When we arrived home, she told Grandmother that she was surprised I didn’t cry when I got the big needle in my thigh. In those days children were rather stoic, so the needle didn’t surprise me, but I was truly surprised by the special, sweet treatment afterwards. This was perhaps the only time I was ever carried on Mother’s back. She even put me to bed that day. Apparently, I was still running a high fever.

It was a bad idea for Mother to carry me home on her back just after having given blood. She had had a heart condition following my birth and was also ailing from beriberi and the heart weakness that resulted from this disease. The doctor had warned that she might not survive, but she had chosen to give birth to me. Her heroic walk with me on her back that day probably contributed to her poor health, which plagued her for the rest of her life. Due to rheumatism, she was partially paralyzed for long periods, mostly in winter, and notably between 1944 and 1946. She was never free of heart problems thereafter.

I saw Mother’s sweet face on a few other occasions. Once when I was a first grader at Nishi-Ōkubo Elementary School, my nose bled, and I lost consciousness. When I opened my eyes in the infirmary, I saw Mother smiling at me. My teacher Kanazawa-sensei had phoned home, but without my knowing, and I was really surprised to see Mother. It was nothing serious, and I was allowed to return to class and dance with the rest of the students. We were performing for the neighborhood that afternoon.

The school was just a short block away. I used to see its flag from the second story of our house. It was my duty to fold the bedding in the sunny second-story room in the morning, and, since the windows were wide open, I could always see the flag in the schoolyard. I think my brother folded his own futon, so what was left for me to fold was my father’s bedding and my own. I used to enjoy doing this in the broad morning sun.

My brother’s first homeroom teacher was Maeda-sensei, a sober-looking, slightly older man. Then in the third grade, Akira had Nagashima-sensei, a young, navy-type man who turned his class into a harmonica ensemble. Once, when Nagashima-sensei saw me with my brother and his playmates on the schoolyard after school hours, he lifted me up in his arms. I turned crimson. A first grader, I thought, was too big to be treated like a little child.

In my preschool days, I often played with Akira and his friends: Mitchan, who was one year ahead of me in school, Chika-chan, and Yoshinobu. Mitchan would come running along the long corridor in our house; I was impressed by how his hair would fluff and then settle down neatly like before. Chika-chan’s older brother, Yoshinobu, came home after the war having lost one arm. He was not very healthy and wore a scarf around his neck, and Grandmother used to say that was why he never grew strong.

Just once, we went to a festival together; perhaps it was along the Ōme Kaidō road. Chika-chan and Yoshinobu bought me a braided string ornament, perhaps for 10 sen (about the same amount as the cheapest streetcar fare). I was afraid of accepting it because my brother and I had not yet been allowed to buy things on the street. I looked at Akira. He seemed to think it was all right. His friends said, “Don’t worry. It’s okay” (iiyo, daijōbu dayo).

Chika-chan and Yoshinobu’s house was to the left of ours. Sato-chan, Yatchan, and Yotchan lived directly to the right of us. Sato-chan was a middle-school student, who carried his school bag across his shoulder. Yatchan was a rascal, perhaps in fifth grade. Yotchan was a crybaby. Once when I was four, Yatchan talked Chika-san and Yoshinobu into hiding my crayons. Yatchan told me that they would scatter my crayons from the rooftops unless I agreed to take off my bloomers. I refused. They repeated that they would throw them off the roof. Since I cared for my crayons more than anything else, I agreed to lower my bloomers. Awed, they demanded nothing more and revealed that my crayons had been stored in the oshiire (closet) all along. I reported the incident to Mother, who told Maeda-sensei. He called me into the parlor after he finished tutoring Akira and asked what had happened. A few days later, as I was walking on the street, Yatchan walked by with his bike. With a strange smile, he asked me if I had told Maeda-sensei. I ran away. As Maeda-sensei had promised, nobody ever bothered me again.

I had thought that Mother wished to provide special learning opportunities for me by inviting Maeda-sensei over for weekly tutoring, but I later learned from her that he had insisted on coming. Being an elementary school teacher, it was never easy to make ends meet if one had a family, and he did. Just before I started elementary school, I was called into the parlor after Akira’s lesson. Maeda-sensei was going to prepare me for a school interview. I always respected him as much as I was scared of him. One of his mock-interview questions was, “What countries is Japan fighting against?” I had no idea. I said, “France, America, China.” I was going to add “Italy, Germany,” but I wasn’t sure, so I didn’t (!)

After this rehearsal, which was also apparently initiated by Maeda-sensei rather than by Mother, I did very well at the examination. For the test, I needed to perform several tasks. Behind one desk a few teachers sat smiling at me. I was told to draw a picture of the Japanese flag. Provided with a few crayons, I began with great pleasure. I felt dismayed when told to stop after just drawing the bamboo flagpole and an outline of the flag. I was going to make a nice red sun against the white background of the flag fluttering in the wind!

Father was home sometimes. I remember a night when he ate dinner late, upstairs next to my bed. He sat in a relaxed manner. Mother served him. There was a small, low table between them. They both smiled. He said, “Have a sip,” offering his soup to me. Although I wasn’t certain if it would be okay, I went to sit near them and had a sip of the clear soup. It tasted good.

Some time later, we had a rare family supper with Father. He was returning to China—either Shanghai or Nanjing. We sat around the dinner table downstairs. He smiled a lot, eating with enjoyment, and then said to me, “Promise me one thing. Learn to eat without chewing with your front teeth.” Mother must have asked him to say this, wishing to correct my habit of pouting as I chewed.

On April 1, 1944, we moved to Narimune in Suginami ward.2 Mother took us to Suginami Daini Elementary School that afternoon. A teacher appeared and said, “Let me put your daughter in class two of the second grade” (Nikumi ni oire itashimashō). This was Hara-sensei. After the school assembly, she took me to her class and wrote my name in hiragana on the blackboard as “Irihe-san.” Of course the hiragana written irihe would most often be pronounced irie and it was of small consequence, though the “e” in iriye was “e,” not “he,” even in the old spelling system. I told her, “It’s Irie, not Irihe.” I shouldn’t have. But Hara-sensei took it with good humor and changed the spelling on the blackboard.

Mother had accompanied me to school the first day, but the second day I was on my own. Coming out of the school, I made a wrong left turn into a narrow dirt path, bumpy with tree roots. I started to look for clues as to my whereabouts. A few children from my class asked me where I was trying to go. One of them, Wada Kazuomi, said, “You just turn left at Nikonikoya-san.” I didn’t know Nikonikoya and was genuinely puzzled, but he kindly accompanied me part of the way. Nikonikoya was the name of a tiny vegetable shop at the corner of Itsukaichi Kaidō road and the street that crossed it. All I needed to do was to turn left at Nikonikoya, walk a short block until it merged with the narrow path that I should have taken, and continue to the right for another few minutes.

Nikonikoya was owned by a slow-moving grandfather. Several years later, when I attended the winter session of Jōsai “preparatory” school, I stopped there a few mornings on my way to get a jam sandwich. I enjoyed watching him slowly slice bread and spread jam.

Wada-kun, the boy who had shown me the way home, wrote with his left hand because his right arm was paralyzed. He did not take part in the student group relocation (gakudō sokai) when our class was later evacuated to the mountains because, as Mother explained to me, his mother thought he would have a hard time. I had hoped he would be going along with the rest of us. Instead, I felt the presence of some adult reason that I could not challenge. His mother was a really nice person. She was round-faced, soft spoken, and always in kimono.

I became friends with Kō-chan, Toyo, Ikuyo, and many others at my new school. After school, Kō-chan and two other friends often invited me to play with them on the harappa (field). We divided into two teams and played what one might call kunitori (dominion) with the princess playing a big role. I simply followed their instructions because I didn’t know what I was supposed to do, but it was interesting running across the field and hiding behind tall grass until the enemy had passed. I was surprised when a boy named Yoshi broke into tears because he lost in “janken” (rock-paper-scissors, a game used to make decisions) and didn’t get to play the princess. Kō-chan sympathized and gave him the right to begin as the princess.

Kō-chan was small and lean but he was a real tyrant. In the fall of 1944, school children were sent out to jinja (shrines) and the woods to collect acorns. Food was growing scarce, and acorns would help. Kō-chan, Toyo, and I were going to a shrine to collect big and small acorns. After crossing Ōkawa, then Ogawa (old name for the Sumida River), when we were very close to home, Kō-chan eyed Toyo and said, “Oi, yaru ka” (Hey, let’s do it). They each gave me a slap on my cheek. I had absolutely no idea what this meant. Kō-chan’s slap was pungent. Toyo’s was hesitant.

That night I had a bad dream. I dreamt that because of the air raid alarms Mother and I were spending the night in the very small shelter dug in the east corner of our yard. My father was in China. Akira was in Shinshū. My grandparents were still in Nishi-Ōkubo. So Mother and I were by ourselves in Narimune. When I awoke in the middle of the night, I saw Mother looking over at me with a smile. She asked what was the matter, so I reluctantly explained what had happened on the way home from acorn gathering. It seems she reported the case to the teacher, Hara-sensei, who comforted me, saying, “Don’t worry. It will never happen again.” It never did.

I went to visit Yoshi a number of times. There was a slope to the west of our Narimune lot that led down to his house. When Mother had to be away, she would leave me lunch on the engawa (veranda). After enjoying it, I would wash and hang my blouse, then practice calligraphy. But on one or two occasions she left a note saying that I was to go to Yoshi’s. I went down the little slope and joined Yoshi and his younger sister for lunch. They had a baby sister, too. By mid-1944, there were only three, or at most four, morning classes at school each week because of the frequent air raids. So I often had lunch at home.

In August 1944, air raids began to strike big cities. By February 1945 we had only two or three morning classes at school and we were sent home whenever the air-raid alarm went off. On February 17, Mother and I hid in the small dugout in the yard as American airplanes approached. When those planes were in the sky—Japan’s air defenses by this time were silenced—we had to stay in the shelter all day and into the night. Mother and our neighbors went in and out of shelters with their young children and cooked between air-raid warnings.

Our shelter was a simply dug hole where there used to be a little strawberry patch. It was just big enough to seat three people. I was not scared by the place but never liked being there because it was damp and slugs crawled about. On December 3, for example, we heard bombing noises that shook the ground. I felt uneasy when Mother handed me a toy whistle and told me to blow it if the shelter collapsed and I was being buried alive. I was also agitated when she said, “If incendiary bombs come through the roof at night, don’t rush to the shelter but cover the fires with quilts and step on them; you are old enough to do this.”

Mother was often out, visiting my grandparents or working for the neighborhood association in a neighborhood without men. I was home alone on these occasions and tried imagining putting fires out by myself. I was trained to sleep with a winter jacket and a backpack near my pillow so I could get ready in the dark immediately when a plane was heard. In those days, we lived in a pitch-dark city; we were not allowed to put on lights at night for fear that enemy airplanes would spot us. If we needed to see, we covered the lamp with a thick, dark cloth so no light would leak outside.

Adults may know how to respond to an abnormal situation, but a child can only accept it as perfectly normal and lasting. I recall the faces of my younger friends at home, faces of acceptance and abandonment. As I later recalled with shock, neither the two-year-old across the street nor the four-year-old next door ever smiled in those days. Their mothers rushed them to shelters without explanation each time the air-raid alarm went off. Young children at this time typically had no expression. I never thought of this as abnormal.

|

Evacuation of schoolchildren in Japan, August 1944. Wikicommons |

Part Two: Evacuation to the Countryside

In August 1944, Akira, then a fourth grader, left for Osamura Sanada, Chiisagata-gun, Nagano Prefecture. That was when systematic gakudō sokai (school children’s evacuation) began. We had gakudō sokai moved from Nishi-Ōkubo to Narimune when evacuation from the heart of the city was encouraged. Now children in the third grade and higher were sent away, even from Narimune, an area of many rice paddies and bamboo groves. The Second Suginami Elementary School sent children to three different areas.

On February 19, 1945, Mother sent me for a haircut, had me rest on the couch for the rest of the afternoon, and gave me a special supper of rice with a slice of fish, a feast the likes of which I had not seen in months. At dusk, I joined the other children in the schoolyard. Each of us carried a backpack filled with textbooks and clothes. Schoolmaster Yoshizumi-sensei led a file of fifty children on a fifteen-minute walk to the railroad station. From there, we rode the train to a big terminal, where we caught a night train to a station named Ueda in Nagano Prefecture. At dawn, we switched to a local train for a one-hour ride.

Schoolmaster Yoshizumi-sensei then walked us through the mulberry bushes. We arrived at Sanada village in the Kōrigata area of Nagano Prefecture on February 19, 1945. When we got off the local train, we did not see any green. It was not yet spring in Tokyo, and, of course, Nagano was even more wintry. I remember crossing a small bridge over a running stream and walking through dry mulberry bushes. In Sanada village, mulberries were cropped short and kept like bushes for the silkworm industry

The dormitory, a converted inn, was very close to the railroad station. In the dorm, over two hundred children lived with four teachers from the Tokyo school and ten locally hired room mothers, ages sixteen to twenty-two. Each room mother cared for a dozen boys and a dozen girls.

As we arrived at the dorm, we could see older children looking out of the windows, waving to us and making us feel welcome. We were temporarily divided into rooms, and I was sent to an upstairs room where Akira lived with eleven other boys. At night there was a roll call. We sat on the tatami in two lines, and the head boy said, “Bangō!” (Count off). We replied “One,” “Two,” “Three,” etc., like soldiers do in the army. I wanted to say “Thirteen!” but I was skipped. The boys wore yukata and obi (cotton kimono with sashes) at night as in peaceful times. I remember seeing Maruyama-kun still in his yukata in the morning as we were putting the futon away in the closet. He soon left to go elsewhere with his family. That sort of thing was called enko sokai (evacuating to join country relatives). As the train that carried him left the station, we waved goodbye from the dorm windows.

Two sisters, Kawashima Toshiko-chan and Reiko-chan, were among the children in Room 13 downstairs. They had lived across the street from us in Narimune. Toshiko-chan insisted that I join them in their room, so the following day I moved there, although I wanted to stay with Akira a little longer. Toshiko-chan was a fifth grader, and Reiko-chan a third grader. It was a small, sunny room, and I felt very comfortable.

Later, there was a shuffling of rooms, and the Kawashima sisters and I were assigned to Room 17, a bigger room with more children. Another second grader was there—the child I had sat with on the train ride to the village. At night, when everyone was asleep, she sat up straight and wept. Twice, I awoke to see her being comforted by the room mother. This continued three days, and then she left. Apparently, her mother was contacted and came to pick her up. We learned that they were moving somewhere, enko sokai style. She was the only child I saw cry.

After we awoke in the morning, we folded and put away our bedding. We went to the small river, which I think was named Kannagawa (the river of the godless month, or October), right near the dorm, to wash our faces and brush our teeth. Then there was a morning assembly in the yard, during which we performed tentsuki taisō (reach-the-heaven calisthenics). The dorm song we sang in the early days of our stay had a line that went: “By the time tentsuki taisō is over, a heap of warm rice will be waiting.” I remember hearing, back in Tokyo, about village women who brought food to evacuated school children on special occasions like the harvest and the New Year. This caused adults to say, “So after all, the country is better for children, food-wise.” By the time my friends and I arrived, however, food was scarce even in the countryside.

|

Children sheltered at Kouseiji Temple, Nagano Prefecture, during the war. Kouseiji Temple Official Website. |

When the gong rang, we went to the dining room with our chopsticks and cups. The cup was for drinking tea, rinsing and gargling in the morning, and carrying one rice ball (without nori seaweed wrapped around it) for lunch when going out for the day’s labor service. Once, when Shinozaki Tsutomu (Akira’s friend and our neighbor) and others ran along the corridor, they were scolded: “Running doesn’t mean you get food faster. Walk properly.”

In the dining hall, children sat in fixed places around rows of simply-built bench-like tables. We joined hands and recited a poem to thank the gods of heaven and earth for the good food. The poem was in tanka form of 5/7/5/7/7 syllables: “When you pick up chopsticks, taste the grace of heavenly and earthly gods, as well as the favors of parents, teachers, and older students” (Hashi toraba ame-tsuchi kami no on-megumi, fubo ya shikei no on o ajiwae). This was followed by a sokai song written by the empress. First, we chanted the poem in a traditional way, somewhat like reading the cards of Hyakunin isshu (a matching game with cards bearing a total of 100 waka poems), then older students sang it to a melody: “You are the ones to shoulder the next era; grow up strongly and correctly by moving to the countryside” (Sugi no yo o seou beki mi zo takumashiku tadashiku nobiyo sato ni utsurite).

Then we all said, “Itadakimasu” (let’s eat), and picked up our chopsticks. Somewhere along the way, I developed the habit of watching people eat, while eating very slowly from my own bowl. It was satisfying to do so. For example, the puffy cheeks of the second son of the Okuda family (who in Tokyo lived close to Ōme Kaidō road) became puffier when he ate. When I saw people had finished half their bowls, then I began eating as fast as I liked. This gave me the joy of eating quickly without having to see others still enjoying their meals after I finished. After an older student criticized me, I had to stop doing this. Sometimes there was a small side dish, for example of one fuki no tō (rhubarb shoot) or three pieces of fuki (rhubarb stalk boiled with soy sauce). We had rice mixed with barley or soybeans at first. This was quite healthy by today’s standard, but many children including myself had become too weak to digest soybeans.

Once, Tokyo mothers got together to send us some butter. Butter was extremely precious in those days, and I had not seen any for a long time. A small square of butter was served on rice on a few occasions. One day, a sixth grader warned children who had diarrhea not to eat butter, so I ate my rice plain. Back in the room she said, “Now I know you have diarrhea.” It was true. She also said other things that were not true. Once the owner of the inn, Mr. Takatō, treated each of us to three thin pieces of preserved squid. The head teacher gave a speech about how kind the owner was and told us to be grateful.

The young room mothers mended our socks and boiled our shirts when lice and gnats infested us. The teachers, three of them also young, treated us with pincers and mercurochrome when our skin diseases spread, and they organized fly-catching contests when the number of flies increased. Many children suffered from malnutrition and diarrhea. A fifth grader was scolded in front of everyone at a morning assembly for having soiled the bathroom. He died some time afterward. The teacher who scolded the boy was known to be patriotic and tough. The other young teachers were gentle. Once when we were helping a farm woman in the field, a third grader who was tired of fieldwork complained, “I hate war. I hope we lose quickly.” A twenty-year-old teacher who was with us gently replied, “Perhaps you shouldn’t say that aloud.”

Mugi (barley) needs to be stepped on when it sprouts in early spring. Called mugifumi this was one of the first tasks for us younger children. We went to a farmer’s mugi field, where green sprouts were just appearing. I was afraid of stepping on them but learned that it made them stronger. At the edge of a section of the large mugi field, we stood in a line, hand in hand, standing on a row of young mugi shoots. We moved forward together, keeping our right feet in front and left feet in back, taking small, rhythmic steps. After we finished the first rows, we saw that the green shoots were standing erect again. Ōtsuka-sensei said we had walked too lightly; we needed to step more firmly to press the tips of the mugi shoots to the soil. With this in mind, we moved on to another section of the field. We never did much better, but, eventually, we at least learned to step down on the mugi tips, not the roots.

We also weeded and removed pebbles from the field, gathered fallen leaves in the forest (for making compost), carried firewood, and cleared rocks from an area of a mountain after dynamite was set. We did the last task by making a long line down the mountain and relaying rock by rock by hand. My friend Hiroko stood next to me, and, as I handed rocks to her hour after hour, I suddenly felt a human sensation: all I touched was the rock that I put in her hands, but I felt the warmth and resiliency of human flesh—with its tenderness, toughness, and thickness—under the rock’s weight. This was so uncomfortable that I became sulky. When I saw her face and realized she was hurt by my bad mood, I forced a smile. That night, after lights out back at the dorm, I heard Hiroko say to an older student in their room across the hall how good it was that, while relaying rocks, I had been distant in the morning but smiled to her in the afternoon. I feared this might be a sort of political demonstration (everyone knew that we could hear each other, even across the hallway, because the rooms were only divided by paper screens); but I felt bad that I had not been nice to her.

It is difficult to explain even to myself why I suddenly felt uncomfortable while handing rocks to her. Certainly the distaste had nothing to do with Hiroko. When I moved from Nishi-Ōkubo Elementary School to Suginami Daini Elementary School in April the year before, I instantly admired her. She was graceful, quiet, and bright without showing off. “Sakura” (cherry) was the word that occurred to me when I first saw her with her very thin bangs. We soon became good friends and remained so, long after the war despite this incident.

Children went to the river and washed their faces and hands every morning and had a bath in the late afternoon before supper. It became less frequent, however. I think by April children were infested by two kinds of lice: one that nests in the folds of clothes and another that nests in human hair.

The first variety was taken care of early by boiling children’s clothes in big pots. One day when our laundry returned to Room 17, where I was at that time, a fifth grader noticed that they were discolored. “Yours wasn’t this color, either,” she said to me pointing at my now grayish flannel shirt that I had inherited from my brother, who had inherited it from my mother. I had no particular feeling about it and was rather shocked by the accusing tone of the older student. Some time later, our room mother came in and formally apologized in an icy tone. Another room mother had told her what she had overheard, “I am sorry, but I did what I thought was good for you.” The room was hushed. One or two older students, especially the one who had included my blouse in her list, offered one or two lame excuses, but the tension only mounted. We were all seated on the tatami floor, our knees formally folded under us, and our room mother seated before us in the same way.

All the dormitory room mothers dressed in kimono, except for the nurse, who was responsible for a very small room with five or so students, in addition to simple medical duties. She wore a white Western gown. Whenever we went out for a whole day of kinrō hōshi (work service), our room mothers sat together to make onigiri. The nurse made sankaku-onigiri (triangular onigiri), although the others made round ones. We gave them the cups we used in the morning to rinse after brushing, and they put one onigiri in each. The onigiri was plain rice without nori but had one umeboshi (sour pickled plum) inside.

Later, I was shocked to recall that all these room mothers were very young. The oldest one, Naitō-san, was in her twenty-fourth year (which means she was twenty-two or twenty-three by the Western count). Utsumi-san, my room mother, was in her twenty-second year.

In the early days, sometimes we went to the village school in the afternoon after village children had gone home. Ishikawa Masumi-sensei, then about twenty-three, once got upset in math class because few of us remembered the times tables. He excused me from class because I could recite them. I didn’t know what I was supposed to be doing while outside the classroom and had a terrible time loitering in the wooden corridor that opened to the sunny schoolyard. I instinctively knew I was not allowed to go into the yard, but then there was nothing inside except the getabako (built-in shoe shelves) near the exit. I felt I should look interested and engaged, as the time passed very slowly until the end of that class.

Later, we had classes at the dorm, but rather infrequently. In one class, Ishikawa-sensei taught us the song of fireflies: “The fireflies’ lodging is the willow tree by the river” (Hotaru no yado wa kawabata yanagi). He also taught us a song that included the line, “Sing away. Singing is your work” (Chichi chichi chitchi chi, chichi chichi chitchi chi, naku no wa omae no shigoto ja naika). I remember these two songs because they struck me as somewhat unusual since they had nothing to do with war ethics.

Actually, we had many songs that had nothing to do with war. We often assembled to have a kodomokai (children’s gathering), at which groups of children presented songs, dances, and skits, made up and rehearsed by children on their own or coached by room mothers. One dance I remember particularly well was performed by four older children from my room. They danced with janome (brown oiled paper umbrellas with a swirling black design with a large white circle (or “snake eye”) toward the top), in the absence of real parasols, to a song that went: “A pictured parasol turning round and round. Please pass it” (Ehigasa kurukuru tōryan’se). It was so beautiful that I thought it unfair when the head teacher Takeichi-sensei commented that it was good but too lonely.

There was Kondō-kun—from the big house of Kondō Heihachirō near our house back home—who always had something fun to perform. The first time I heard him sing, I had a high fever, but the nurse kindly carried me to the hall. He was singing a song about the fairy-tale hero Issun-bōshi (One-Inch-Tall Samurai): “In the castle of Heidelberg, there lived a boy as tiny as a thumb named Perukyo” (Haideruberugu no oshiro no naka ni issunbōshi no Perukyo ga sunde ita, . . . issunbōshi no Perukyo wa kō itta: ah haideru haideru rō, ah haideru haideru rō, ah haideru haideru haideru rō, ah haideru haideru rō). Although the songs he sang were humorous, he always looked very serious, sitting small with his knees and hands together on the tatami floor. He also sang the Shinshū folk song “Kisobushi”: “What’s the thing about Mt. Nakanori in Kiso? It’s cold there even in summer” (Kiso no Nakanori-san, Kiso no Nakanori-san wa nanjara hoi, natsu demo samui, yoi yoi yoi, yoi yoi yoi no yoi yoi yoi).

I learned many other songs. The following two were my favorites:

| Land of Sleep | Nen’ne no osato |

| Clovers in the land of sleep | Nen’ne no osato no gengesō |

| Here and there calves are grazing | pochi pochi koushi mo asonderu |

| Clovers in the land of sleep, of sleep | nen’ne no nen’ne no gengesō |

| Someone is calling from afar | dareka ga tōku de yonde iru |

| Fall Festival | Akimatsuri |

| Drawn by pipes and drums | Fue ya taiko ni sasowarete |

| I’ve come to the village festival | mura no matsuri ni kite mireba |

| At dusk, more and more I miss town | higure wa iyaiya sato koishi |

| When winds blow, all I hear is the sound of leaves | kaze fukya konoha no oto bakari |

The second song was written by the poet Kitahara Hakushū. The melody was probably composed by Yamada Kōsaku.

There were others, including “Seagull Sailors” (Kamome no suihei-san), “The Seven Seas” (Nanatsu no kuni), and “Festival in the Woods” (Mori no matsuri). The latter two songs were colonialist, meant to excite children about Asia and the South Pacific. My friend Mori Masayo-chan and others danced the “Festival in the Woods,” which went: “Tonight is festival night on Barao Island; together with the islanders, we dance with joy” (Kon’ya wa omatsuri Barao-tō, dojin-san ga sorotte omoshiroku, a hōi hōi no donjara hoi). “Omoshiroku” probably means both “amusingly to spectators” and “having fun themselves”; I’m afraid that either way it’s insulting.

The songs that Ishikawa-sensei taught us, which I described earlier, were neither like the brave, pathetic war songs that we were taught in Tokyo nor like the folk songs and children’s songs that were sung in the dorm in Nagano. The children’s songs I learned there were nostalgic, evocative, and minor-keyed, whereas these in major keys were light, modern, and colloquial. I really didn’t know what to think of them. Now that I think back, it occurs to me that Ishikawa-sensei might have deliberately introduced them because we looked so serious and devoid of humor. He, too, displayed no sense of humor. He was quiet, surrounded by a kind of pathos. He was Akira’s homeroom teacher back in Tokyo. In Nagano, he occasionally taught us third graders.

Our main teacher was Murai-sensei whom everyone loved. She was quiet, modest, and gentle—maybe even shy. She was dark-complexioned and oval-faced, with kind-looking dark eyes. Then there was Ōtsuka-sensei, who was more outgoing. Teachers often used megaphones to summon students to the teachers’ room. I remember Ōtsuka-sensei calling me from the corridor at a railing that opened into the yard. I saw her stand with a megaphone and felt exalted when she called me in her non-standard accent: “Iriye Kyōko-san, Iriye Kyōko-san, come to the teachers’ room.” She pronounced my name with a pitch accent on the first and last syllables: “I-riye Kyo-oko-san.” When I went there, she told me to go on an errand to the cottage where the Maruno family was staying.

Mr. Maruno, a Japanese literature teacher at Meiji University (if not then, at least later), seems to have been one of my grandfather Tsukamoto Tetsuzō’s protégés—colleagues at one point. We shared a home in Narimune before moving to the countryside. He was a Kyūshū danji (a stern male chauvinist from Kyūshū) whom everyone feared. He awoke at five or so in the morning and jogged to Hakusan jinja (the small, discarded nearby shrine). I joined Mr. Maruno and his boys just once. He was reticent but scary. One morning, while I was brushing my teeth, he came to the senmenjo sink that our two families shared. My mother was shocked and told me to use the sink only after he had used it, but Mr. Maruno was really nice and shared the water with me. My mother told me that in Kyūshū men were revered; the head of a household was so important no one could take a bath before him.

Just once I saw Mr. Maruno in action. At the end of the first semester of 1944 (I think), when I came home, I saw Yutaka, the younger of the two sons, then a sixth grader, seated straight in formal posture, head down, across the small table from his father in the six-mat room. My mother told me Yutaka got a ryō-ge (a B minus) in math and was being scolded. (Yutaka was a good student. He read out loud the passage about the famous archer Nasu no Yoichi in the original language from the Tale of the Heike so eloquently3 that I heard him from our side of the house and instantly learned the story.) From that day on, Yutaka had to sit before his father every day to review math. This didn’t last long because the semester ended on July 25, and on August 4 or so, most students in the upper elementary school grades were sent to the countryside. Yutaka went to Osamura Sanada in Nagano to the same dorm as Akira.

The Maruno family lived in the Narimune house for a few years. There were two boys in the family, Hiroshi-chan and Yutaka-chan. By the time he graduated from primary school in March 1945, Yutaka-chan had become so fond of the relaxed rural life that he insisted that the family move there. So, leaving Mr. Maruno in Tokyo, Mrs. Maruno and Hiroshi, then a student of Toyotama Chūgakkō junior high school, joined Yutaka in our village. They lived in a cottage by the farmhouse of our room mother Utsumi-san’s parents.

When there was something to be delivered to the Marunos while they were staying at the Utsumis, I was called to the teachers’ room. This was a great privilege because I could drop whatever I was doing and go out into the wide countryside, although it probably happened just two or three times. Once Mrs. Maruno took me to the main house to introduce me to Utsumi-sensei’s mother. Mrs. Utsumi, who wore a dark monpe suit and a white tenugui towel wrapped on her head, handed me a Shinshū style onigiri with a little miso on the outside. I took it from her with a thank you, and then with difficulty tried to split it. “Let’s share it” (Hanbun zutsu shimashou), I said to Mrs. Maruno, who smiled and told me to enjoy it by myself. I felt bad, but I did as I was told. It was so good. I don’t remember what I brought to Mrs. Maruno. Maybe a package of tea or nori from a Tokyo neighbor.

One day, Ōtsuka-sensei and Ishikawa-sensei took the third and fourth graders out for work. In the morning, we packed straw bags with fallen leaves in the woods, and then we walked some more and had lunch. After lunch, Ishikawa-sensei and Ōtsuka-sensei said that we would climb the mountain, but those who didn’t wish to could return to the dorm. Half the children left. The rest of us walked in double file, as always, along a narrow mountain trail. I was thrilled to be climbing and didn’t understand when children dropped out one by one, fourth graders first and then third graders. Pretty soon only five of us were walking with the two teachers. The group was Yano Hiroko-chan, Ogawa Toshiko-chan, another third grader, myself, and fourth grader Harada Ritchan. No longer in double file, we walked a long distance along a somewhat wider, mostly level, trail that cut through a shady forest. There was much snow off the trail and on the tall trees. We went off the trail to play tricks on each other, putting snow in each other’s collars. The teachers warned that there might be bears around there. Perhaps they wished to entertain us or perhaps they didn’t want us to wander into the dark woods. After some more climbing, the view suddenly opened up as the tall trees ended. We saw bright green grass and leaves in the sun and a panoramic view down on the left from where we stood. We walked more along the narrow trail on the side of the mountain and then came to a wide, snow-covered field.

Ishikawa-sensei said, “Wait here for a bit. We will see if we’re on the right path” (Kimitachi wa kokode matte inasai, Michiga tadashiika dōka mite kurukara). So we sat on the snow and waited. I retraced the track about fifty meters and went off the trail by myself for oshikko (to pee), and when I started back again, I saw the teachers in the distance. Ōtsuka-sensei shouted, “Everyone, let’s go” (Minna irrasshai), and, seeing me further back, added “Kyoko, too, hurry up” (Kyōko-chan mo hayaku irrasshai). When I joined the rest, Ishikawa-sensei said, “The path was all right. Just ahead is the summit. So let’s go see the view.” There was a two-arrowed wooden landmark on the wide summit, which read more or less “Nagano this way, Gunma that way.” Ishikawa-sensei said, “Those of you here have come to the border of Nagano and Gunma prefectures” (Koko ni iru kimitachi wa Nagano to Gunma no kunizakai made kitanoda yo). We gazed at the gentle slope down to the Gunma side. I was reluctant to leave this place.

It was dark by the time we approached the dorm. We heard voices calling us. At first I didn’t know what this meant, but, when we were met by Kawashima Toshiko-chan and other older students, we learned that they had been looking for us.

I so fully enjoyed the excursion through the dark forest that led to a bright open view and snowy plain at the summit that I didn’t understand why we had caused such worry or received such a warm welcome. But it was against the dorm practice for a group to split up or be late for meals. Apparently, the two teachers were held responsible for leaving the rest of the children unwilling to make the trip alone, and for disappearing briefly by themselves near the summit. I excitedly wrote home about the climb; others probably did the same. Letters home and letters from home were censored. Maybe the dorm master who read accounts of the trip liked the two teachers’ behavior even less; or parents were upset. Nothing happened then, but after the war they were dismissed from school. Murai-sensei later returned and taught until she got married in 1946.

If anyone knew how wrong it was to return late to the dorm, it was Ishikawa-sensei. One evening after supper a certain Satoko-chan took two younger children out for a walk and did not return for the roll call and lights out. We had just gone to bed when we heard Ishikawa-sensei scolding Satoko-chan in the corridor near our room. He was saying things like “responsibility” and “taking little children.” We were hushed, wide-eyed in the dark. Then we heard a slap, Satoko apologized, “Gomen nasai” repeatedly through her tears, but there were several more slaps.

Ishikawa-sensei looked reticent and distant with a gentle manner. This frightened us all the more. Satoko-chan, a Korean, was a kind girl whom smaller children liked a lot. She had short okappa (bobbed hair) and dark, shiny eyes under double eyelids. When I lived in Room 17, she lived next door in Room 16. Once she opened the center sliding door just slightly, and in a low, sing-song voice, whispered through the crack, “You say Satoko, Satoko making fun of me; how can we be different, we eat the same rice (Satoko Satoko to baka ni suru, onaji kome kutte doko chigau). This was a parody based on a couplet that condemned discrimination, and, although meant to be a joke, it was too sad to be funny. I wrote it here with some reluctance, fighting a suspicion that occurred to me for the first time that her being Korean might have made it easier for Ishikawa-sensei to slap her. This was the only time I saw a teacher slap a girl. Actually, slapping did not happen as often as might have been expected at a wartime dormitory.

It’s interesting to recall that some older students were more militaristic than the teachers. In the dorm, most boys lived on the second floor and one small mezzanine, but one of the dark back rooms on the first floor was also occupied by boys. There were at least three back rooms. One was Room 9 where I stayed, another was for the room mothers, and Room 10, the darkest room where no light penetrated, was for boys. Apparently, the room representative, then an occupant of Room 6, volunteered to move during a room reshuffling in April at the beginning of the new school year. He said, “We’ve lived in the sunniest room until now, so we should move into the darkest room.” He exercised his leadership with the same rigor and righteousness. I saw him scolding a few younger boys from the same room because someone had toppled over a flower vase and nobody had picked it up. One of the boys was Shinozaki Tsutomu-kun, a fifth grader and my brother’s classmate. Standing straight with all seriousness and without blinking when slapped on the face, he said, “I sincerely apologize” (Mōshiwake arimasen!). I thought this reflected the army manner. In the army, it was said to be wise to make no excuse but instead apologize quickly and properly. Saying “sumimasen” (sorry) was not good enough because the angry officer might say, “Do you think you can get away with sorry” (Sumimasen de sumu to omou no ka!).

Shinozaki-kun was from a house close to ours, and he and Akira often played together in Narimune. At the dorm, the three of us shared candy on the rare occasions when Akira received a package from home. We stood side by side facing the back of the dorm, just a little way up the hill in back, and enjoyed the secret taste of something like umeboshiame (pickled plum candy). Nobody looked as generous and dependable as Akira holding a small can on the mountain.

It’s not that Akira and I couldn’t see each other. I was free to go upstairs to see him anytime. But it didn’t occur to me to go to him, especially after the first few weeks. One of the rare times I did was when I carved chopsticks out of a joint of bamboo with a kogatana knife. I went to show them to him. Screen doors between rooms were usually closed, but those facing the hallway were open. So when I went to Akira’s room, I would lightly knock. I showed the chopsticks without entering the room. Akira looked at them, smiled faintly as if mildly embarrassed, and Shinozaki-kun or another of Akira’s friends approached to see what I had made. Then he quickly fixed the clumsily carved chopsticks with a kogatana and sandpaper and gave them back to me. Some children were very good at making things. A pair of chopsticks that a sixth grader made for a room mother had beautifully carved decorations at the top. They also made takeuma (stilts) and walked on them in the front yard.

But I was talking about Akira. He never deigned to come to my room, but somehow he must have had a way of communicating with me when necessary. Once or twice it may have been Shinozaki-kun who told me I was to see my brother. Maybe he said, “Your brother wants to see you” (Iriye-kun ga yonde iru yo); or maybe Akira saw me on the way out after breakfast and said, “Let’s meet at the back hill” (Urayama e ikō). Once or twice, Akira said, “Let’s go to the Marunos’” (Maruno-sanchi ni ikō). When I was running to their house, I heard clapping of geta (wooden sandals) on my right, perhaps on the next street running parallel to the one I was on, and I knew it was Akira. I thought of taking a left to join him on a small side alley that cut across, connecting the two streets, but I kept going as before because I wasn’t sure it was Akira. “I heard you, I knew it was you” (Kikoeta yo, sōdarō to omotta), he said when we found each other before the house.

My father returned from China in May 1945. As soon as rail service was partially restored, my parents came to see us.4 It was late July. I had been sent on an errand from the dormitory to the Maruno family’s cottage. No one was there, and, growing tired of waiting, I laid down on the floor. My parents stopped by there on their way to the dorm. When I saw the smiles on my parents’ faces as they arrived at the entrance, I experienced a strange sensation. I sat up but did not walk over to greet them. As they later told me, my blank stare made them think that I was ill. I was ill, but that was not the reason why I did not smile back; I was then not used to smiles. When I returned to the door and began to tell friends that I was happy to see my parents, a sixth grader snapped at me: how could I be happy when everyone was mourning for the Okinawans. She had just learned about Okinawa’s final suicide battle at the dorm assembly for older students.5

My parents wanted to take us back to Tokyo with them the following day. The head master of the dorm yelled at them that it would mean killing their children. “It’s better for the family to die together in Tokyo,” my father said. They prevailed. After a train trip to the nearest city to get a doctor’s diagnosis, my brother and I were released from the dorm.

The countryside had been peaceful and safe from air raids. We were reminded of the war only when we went to the station to see a soldier off. Soon after I became a third grader (April 1945), I had learned about Germany’s surrender from a teacher, but thought of it as a remote event. I was not aware of the hardships my mother and her relatives in Tokyo were experiencing, partly because letters were censored by teachers who thought that pessimistic news would dampen our morale. To children my age, war was a fact that was taken for granted. I never expected the war to end or that I would rejoin my parents. I never thought I was living in an abnormal situation. Even if there were little study, little hygiene, little food, and much physical work, children took such things for granted.

Part Three: Return to Tokyo in the Aftermath of War

Getting off the train in Tokyo, I saw an empty field. During the ten-minute walk southward along what had been a shop-lined main street running parallel to the railway, the only thing I saw was a burnt bank safe. But after crossing the highway, I began to spot familiar sights. Our house was still there. When my brother and I reached the entrance, Grandmother looked at us, speechless and pale. She thought we were ghosts. She had seen many corpses and ghosts following the March and April air raids; besides, we were ghost-thin from undernourishment. In fact, she, too, was ghost-like, and she, my mother, and I took turns staying in bed during the next few years.

When we sat for supper together that day, I was shocked to see slices of beautiful tomato from the yard and cornmeal rolls, an unbelievable feast after the starvation diet in the countryside. Although every meal was cornmeal rolls or sweet potatoes for a while, they were so good compared with the dorm food that each time I overate and lay on the floor in pain until I got used to the idea that there was food at home.

It is difficult to talk about my childhood without referring to what other children and students were going through when I was in the peaceful countryside or at home comfortably for the last two weeks of the war. My cousin in the first grade, and her family lived in a small town near the city of Hiroshima. Right after the bombing, her father, an amateur photographer, went to the city with his camera. Because my cousin was missing, her mother walked all over town and toward the city. Both of her parents became quite ill later from exposure to radiation. With diarrhea, vomiting, and lost hair, they were each bed-ridden for an extended period of time. Following the explosion, all communications were cut off in Hiroshima, and we could send neither a telegram nor a postcard. When transportation was restored, my uncle visited us before he had any signs of radiation illness. He told us what he had seen. Among others, he saw a girl about thirteen or fourteen, heavily burned, her face swollen like a balloon; she took two or three slow steps toward him, her arms raised, and then collapsed.

I was a third grader when the war ended. At noon on August 15, 1945 my grandfather and father were at work. My grandmother, mother, brother, and I crossed the street to a neighbor’s house to listen to what we were told would be an “important radio broadcast.” It was the emperor’s address to the nation regarding the surrender. When we returned home after the one-minute announcement, my mother sat us down and told us what it meant.

“Japan lost the war,” she said. “The American Occupation will start soon, but you need not worry.” She was, in fact, rather concerned about the Occupation because, when she was in Paris in June 1940, she had witnessed what happened when the Germans entered.

Before breakfast the following morning, she sent my brother and me to my father’s study. He told us that Japan’s defeat was due to a lack of learning and to ignorance of the international situation and that the next generation needed to study hard with a broader vista. Later when my mother asked him what could be expected of the Occupation army, he said, “Americans are gentlemen; there is nothing to worry about.”

The defeat was also explained to children at school. At our public elementary school surrounded by rice fields, the schoolmaster withdrew, accepting responsibility for having cooperated with the war effort, and the vice-master, who seemed to me to have been more nationalistic, became the new schoolmaster. He spoke to the children gathered in the schoolyard, “Japan made mistakes. Every one of us was at fault—we adults as well as you children. We are all responsible for these errors. There is no need to look guilty, however, when the Occupation force lands. We should instead try our best to reconstruct our country and rejoin the nations of the world, this time as a peaceful country.”

I felt uncomfortable about children being held responsible for the war, but the new catchphrase—“peace and reconstruction”—sounded more attractive than the old one to which we had become accustomed—“determination unto death.” The new schoolmaster added that one error in the past was educating children in such a way that they grew to adulthood too quickly: children in the past were taught to fight for the country and to die for the cause. But now, children didn’t have to die; they would be allowed to be children. I found this insulting. Until just days before, we had been expected to behave like responsible adults. Now we had to be baby-like, as if we could change overnight. Something else was gravely wrong about what he had said: encouraging children to be babies kept us from thinking about what had gone wrong. Anyway, children had been trained as little adults during the war.

My third-year class blackened portions of our kokugo (Japanese) and shūshin (ethics) textbooks with brush and ink. I was a little sad that I had to blacken the story of Tajimamori. Following an “imperial” order, Tajimamori went to China to look for an orange tree (tachibana). After many years, he brought back a branch, but by then the emperor had died. Tajimamori visited the tomb and cried. Apparently, the story had been banned because of the phrase “although he was Korean.” I didn’t know it then. I simple-mindedly thought that it was bad because it was a story related to an “emperor.” Things related to emperors were suppressed then. Actually, this legend belongs to a time when the word “emperor” (tennō) was not yet in use.

We used brush and ink to blacken textbook pages that had references to Shinto myths, the Imperial Household, the Imperial Army, and the colonies. We were already familiar with the stories in the wartime textbooks for every grade, but the symbolic message was clear to us: our teachers had been teaching the wrong things. We continued to remember these stories, especially those about battles and tragic heroes and heroines from the olden days. In the new textbooks given to us starting in 1947, there were instead dull stories about ordinary postwar children and adults. If there were any heroes at all in our new fifth-grade Japanese language textbook that came out in 1947, they were industrious heroes like the founder of the Mikimoto pearl company and the inventor of the weaving machine, or Lincoln, Washington, and Columbus. I now find the blackening of the textbooks much more poignantly symbolic than I did then: it is as if the authorities believed that the act could wipe out the wrong ideas and wrongdoings of the past. Blackening pages neither changed children’s mentalities nor obliterated the past; this was not a meaningful substitute for taking responsibility.

In March 1946, the school gakugeikai (arts festival) was held as usual. I participated in the play as the nighthawk (yodaka) in Miyazawa Kenji’s story “The Night Hawk Star” (Yodaka no hoshi). Akira was in the chorus for the fifth graders’ production of a play written by one of the teachers. In this play, Jirō, a child living with his father who is ill, works as a shoeshine boy near the train station. His homeroom teacher spots him and gives him 200 yen. The boy places the envelope containing the money by his father’s bedside. While he is out, the father discovers the money, suspects the boy of theft, and orders him out of the house. The boy wanders to the outskirts of town, empty after air raids, singing the following song to the tune of “Sagiri kiyuru”:

| Out of the house forlornly | Ie o idete tobotobo to |

| Jirō came to the edge of town. | Jirō-kun wa machihazure |

| Yes, the burnt-out town is desolate. | Geni yakeato no sabishisa yo |

| The wind is cold under the midnight moon. | Kaze mo samui, yowa no tsuki. |

Akira and I sang this song many times at home. Our cousin Yoriko happened to visit Narimune with her mother around this time. She liked the play so much that she performed it again and again, impersonating Jirō. “Ah, the moon. The moon” (Otsukisama, otsukisama), she would call the way that the forsaken Jirō did.

Shimamura-sensei, Akira’s homeroom teacher who wrote the play and played the role of Jirō’s father with finesse, gave three pieces of candy to every student in his class on graduation day the following year. “One is for yourself, one is for your parents, and the remaining one is for your sibling,” he said. So Akira gave our parents one and gave me one. I think Shimamura-sensei was really saying, “None for the country. None for the emperor.”

Part Four: Reflections

I talk with uneasiness about Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki as I become more aware of Japanese war atrocities. At the same time, I see no point in balancing two things, as in much of the debate over the 1995 Smithsonian exhibit of the Enola Gay and the suppression of the exhibition on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki6: Hiroshima versus Pearl Harbor, Japan versus the United States, Americans versus Japanese, Japan’s indiscriminate city bombings in China versus the United States’ city bombings in Japan.

These dichotomies are typically intended not for learning about war atrocities on both sides but for justifying, minimizing, or absolving one or the other. A Japanese should not feel less compunction about the rape of Nanjing because of Hiroshima; likewise, no one should feel better about Hiroshima because of Pearl Harbor. Nor does it make sense to me to say Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Tokyo were crueler than other cases of destruction because the death tolls were the largest, or that they were less cruel because those cities are said to have been wiped away instantly: 1) It is disrespectful to reduce humanity to numbers, and 2) many deaths were slow and cruel. “Is it okay to kill only a few? Is it okay to kill slowly?” as poet Ishihara Yoshiro asked. The writer Hayashi Kyōko mentions a Nagasaki factory worker who survived the bombing for a day or two. He was in such pain that he tore his flesh. In Tokyo, my grandmother witnessed forty air raids in one and a half years before her neighborhood was finally flattened.

To me, all city bombings are cruel, and every war is cruel; there is no such thing as a good war. What I see in Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki is humans harming fellow humans, involving all types of people: scientists, political and military leaders, weapon makers, bomber pilots, soldiers, POWs, neighbors, relatives, and friends. They harmed others and one another. And when children do not smile, there is something wrong.

Afterword by Akira Iriye

Because I was two years her elder, I preceded Kyoko as a resident at the Nagano hotel turned into a refugee camp for school children to escape the anticipated saturation bombing of Tokyo. Neither during our stay at the camp nor later did we discuss our experiences. This may have been because, as Kyoko notes, we were too hungry from lack of anything to eat and too exhausted from daily work outdoors to have the energy, let alone the incentive, to engage in a family-style conversation. Perhaps such conversations may be possible only in peace.

So it comes as a surprise to me that she was keenly aware of what was going on around her and thought very carefully about it. I did not know that she was writing a diary in those days, and so she must have kept her thoughts to herself, only to resurrect them from memory years later. Indeed, it is amazing that she retained so vivid and precise a mental record of what she was observing at home and in the Nagano camp.

I have forgotten, or have chosen to forget, all such conversations with my parents and teachers. To be sure, I remember the day when our parents returned from Europe in the spring of 1941, after having been away from Japan for four years (three years in my mother’s case). I had just started school as a first grader and, at first, didn’t even recognize them. We had been raised by our maternal grandparents. Shortly after our family was reunited, Japan attacked the United States. My father went to China as a correspondent for the Domei Press, and in 1944 our family moved to Suginami Ward on the western edge of Tokyo. My mother, my sister, and I lived there for a few months before I was moved to Nagano, where I spent ten months (September 1944 to the end of July 1945) in a horrible environment of hazing and lice (but no rice).

I tried to keep a diary at Nagano but gave up after my roommates took it away, read the entries, and made fun of me for what I had written. So it was a genuine relief when our parents visited us at the end of July 1945 and decided to take us back to Tokyo, even though the war had not ended. (Our father had returned from Nanjing in late May in what would turn out to be the last ship carrying Japanese from China that was not sunk by U.S. submarines.) The last two weeks of the war (July 31 to August 15) were thus a blissful contrast to the preceding several months, even years.

To me, Kyoko, and millions of boys and girls our age, the war was an unmitigated disaster from beginning to end, and the wartime relocation experience was the worst phase of my life. As soon as the war ended, I must have decided to forget this evil past and focus on the future. I started keeping a diary on August 19, 1945. Its daily entries reflect a sense of relief, even joy, at Japan’s defeat. The war years were the worst time of my life. It comes as a shock that some of the younger generation in contemporary Japan seem to have a more benign image of the long, disastrous war, even to the extent of justifying the nation’s aggressive acts against its neighbors on the continent and across the Pacific. One can only hope that the bridges and networks that have been built up so patiently in the wider Asia-Pacific region since the war, and particularly since the 1970s, will prove to be much more solid than temporary shifts and turns in national moods or geopolitical disputes. Our task is to connect, not divide, the world.

Notes

Akira is two years older than Kyoko. Their parents Keishirō, a journalist, and Naoko, had left for Paris in 1939, eventually returning to Japan on the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok and then by boat perhaps to Niigata before arriving in Tokyo by train. They had just boarded the Trans-Siberian when they heard the news of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Keishirō would leave shortly for China, where he would spend the war years. Their maternal grandmother Tsukamoto Man raised Kyoko and Akira while their parents were in Paris and lived with the Iriye family thereafter. (Kyoko poignantly describes her grandmother’s death in the poem “Three Landscapes” included in the Review of Japanese Culture and Society XXVII special issue.) Their maternal grandfather Tsukamoto Tetsuzo (1881-1953) was a leading teacher of Chinese and Japanese classics and a prolific author whose works included widely used study guides and annotated readers of the classics. Kyoko’s first teacher of the classics, he was an aficionado of calligraphy and kanbun poetry (poetry written in Chinese).

Nasu no Yoichi (1169-1232) was a famous archer who fought on the side of the Minamoto clan in the Gempei War (1180-85). In a passage in the Tale of the Heike, the Taira placed a fan atop one of their ships and dared the Minamoto warriors to shoot it off. Nasu no Yoichi, seated on his horse in the water, did so with a single shot.

Beginning with the firebombing of Tokyo on the night of March 9, 1945, sixty-four Japanese cities were eventually destroyed by bombing and napalm, creating tens of millions of refugees and destroying much infrastructure including railroads, roads and bridges.

The Battle of Okinawa, which raged most fiercely from mid-April to mid-June 1945, was the bloodiest of the Pacific War for the Japanese as well as U.S. forces, and took the lives of one quarter to one third of the Okinawan population.

A planned exhibit on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was canceled when the U.S. Senate, outraged at plans to include the charred lunchbox of a Japanese child, voted unanimously to replace the nuanced historical presentation of the bombing with a single object: the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima.