|

Chiri Yukie and Kan’nari Matsu. Date of photograph unknown. Wikicommons. |

Chiri Yukie (1903-22) was born in Noboribetsu, Hokkaido to Chiri Takakichi and Nami. Nami was the daughter of a Hokkaido Ainu grandsire, Kan’nari. Yukie was the older sister of the linguist Chiri Mashiho (1909-61). When she was five and six years old, she lived in Horobetsu with her grandmother, the great bard Monashinouku. Yukie grew up listening to recitations in the oral tradition as narrated by Monashinouku and later also by her adoptive mother Kan’nari Matsu (1875-1961), Nami’s sister. Starting in 1909, she and Monashinouku lived with Matsu at the Episcopal Church compound in Chikabumi in the suburbs of Asahikawa in Hokkaido. After a total of seven years of normal and higher normal school education, she attended Asahikawa Girls Vocational School for three years, graduating in 1910.

When the linguist Kindaichi Kyōsuke visited Matsu in 1918 during a research trip to Hokkaido, he learned that Yukie, too, was versed in oral tradition. At his encouragement, she began transcription. In 1921 she sent Kindaichi a manuscript that she called A Collection of Ainu Legends (Ainu densetsushū). She stayed with the Kindaichis in Tokyo in 1922 to edit the collection for publication. Hours after completing it, she died of heart disease.

|

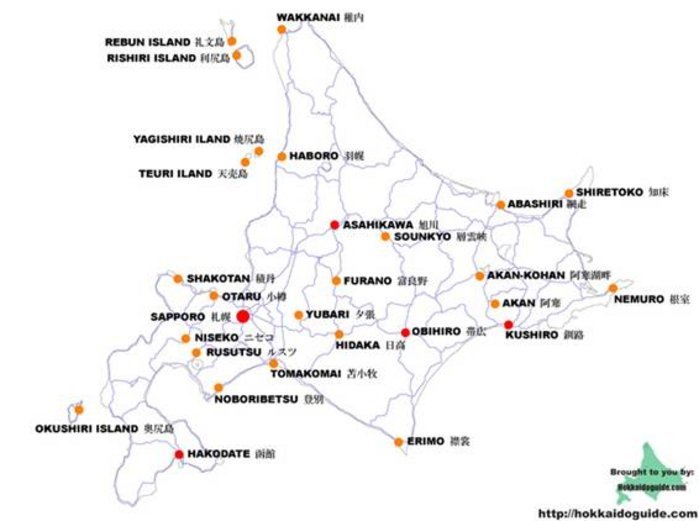

Map of Hokkaido showing Noboribetsu. From the Japan Focus Version, January 24, 2009. |

The work was published in 1923 under the title Ainu Songs of Gods (Ainu shin’yōshū) by Kyōdo Kenkyūsha, a publisher presided over by the ethnologist Yanagita Kunio. The book has been included in the Iwanami Library since 1978. In addition to Yukie’s preface, her romanized transcription of the original Ainu songs with Japanese annotations, and her modern Japanese translation, followed by Kindaichi’s afterword, the Iwanami edition appends Mashiho’s scholarly essay on songs of gods. Whereas the first edition stated that the work was “Compiled by Chiri Yukie,” the Iwanami editors corrected this to “Compiled and Translated by Chiri Yukie.”

The Japanese word shin’yō is a translation of kamuy yukar, a song in which, in principle, a nature god speaks in the first person. This is distinct from yukar, a long epic about human heroes, and uepeker, prose folk tales. Kamuy yukar, narrated in patterned literary Ainu as is yukar, always contains a refrain called sakehe that differs from song to song, and often ends in a colloquial phrase like ari . . . kamuy yayeyukar (thus the so-and-so god sings about himself, or mimics himself in the form of a song of a god) or ari . . . kamuy isoytak (thus the so-and-so god tells his tale). Kamuy yukar was customarily sung by women, while yukar was traditionally sung by men, although female bards took over the latter by the mid-twentieth century when few male bards were left.

Yukie’s book contains thirteen songs of gods, such as the owl, fox, rabbit, little wolf, sea, frog, otter, and swamp mussel deities, and the spirit of the damp ground. “Silver Droplets Fall” is the first in her collection, and one of the two owl god songs. The owl (or more precisely, in Horobetsu, Blakiston’s eagle owl) is kotan-kor-kamuy, the guardian god of the kotan (hamlet).

|

Chiri Yukie (1903-1922). Date of photograph unknown. Wikicommons. |

The English translation here is based on Chiri Yukie’s Japanese translation in the Iwanami Library edition of Ainu Songs of Gods (1978). Her Japanese notes on the romanized Ainu text are also included because they provide useful information. Her spelling is retained wherever she uses Ainu expressions, although the spelling system has changed since then. Her line division is also honored as much as possible, while recent Japanese translation practice is to divide lines more closely to reflect metric patterns of the original. Another translation into Japanese of the piece by Chiri Mashiho in Appreciation of Yukar (Yukar kanshō, 1956) with his annotations and a commentary by Oda Kunio, is reproduced in Hanasaki Kōhei, The Islands Are a Festoon (Shimajima wa hanazuna, Shakai Hyōronsha, 1990). Mashiho’s version pays closer attention to the metric pattern and literary devices of the original, such as parallelisms and repetitions, providing a basis for subsequent translations of kamuy yukar and yukar. There is a difference in the treatment of the refrain as well. Yukie interpreted it to say “Silver droplets fall,” while Mashiho took the word “fall” as imperative, meaning “Fall, you silver droplets.” He also argues that the title means “the song the owl god sang of himself” rather than “the song the owl god sang himself.” These and other differences aside, most Japanese readers still go to Yukie’s version, which has historical weight as the first published transliteration and translation from Ainu oral literature by an Ainu in any language.

Doubts may arise about the logic of transcribing traditional oral performances into a written text, whether romanized or rendered into Japanese. Or, for that matter, into English. Yet such transcriptions preserved Ainu tradition from oblivion. Consider Kayano Shigeru’s great cultural preservation project, Kayano Shigeru’s Collection of Ainu Mythology (Kayano Shigeru no Ainu shin’wa shūsei, 10 vols., Bikutā Entateinmento, 1998). Based on years of making recordings of recitation by elderly bards, Kayano provided CDs, as well as the romanized text, kana transcription, Japanese translation, and annotations. Kayano’s efforts extended to attempts to preserve the Ainu language for future generations. For example, Sapporo Television started an Ainu language lesson program in 1999 with Kayano as the original instructor. It continues today with elderly and younger Ainu lecturers from different areas of Hokkaido representing Ainu local dialects. (Kayano’s children’s book The Goddess of Wind and Okikurmi is included in this issue.)

Similar attention to the sound has been paid to Yukie’s thirteen kamuy yukar in recent years. The Ainu language researcher Katayama Tatsumine (1942-2004) and the Chitose-born bard Nakamoto Mutsuko (1928- ), who earlier collaborated on the text and recording of Kamuy Yukar (1995), in 2003 published a CD version of Yukie’s Ainu Songs of Gods (Sōfūkan).

The CD contains Nakamoto’s singing in Ainu, Japanese recitation by Kurotani Masumi, and English reading by Julie Kaizawa. Again, NHK public television’s widely-viewed weekly series History Moved at That Moment (Sono toki rekishi ga ugoita) featured Yukie in October 2008, placing similar importance on her as on the central characters in the other four installments in the same month: the Sengoku warrior Azai Nagamasa, Chinese heroes of the Three Kingdoms, the late-Tokugawa Shogunal wife Atsuhime, and the novelist Murasaki Shikibu. Here, too, the program included Nakamoto’s oral performance of passages from Ainu Songs of Gods.

Direct Ainu-to-English translation by Donald Philippi of the two songs of the owl god from Yukie’s collection appears in his Songs of Gods, Songs of Humans (Princeton University Press/The University of Tokyo Press, 1979). Listening for the original rhythm, Philippi freely divides lines, using even shorter lines than did Mashiho. He also sets off the refrain from the rest of the text. His translation is from Ainu oral tradition as transcribed by Yukie. The following is the first English translation from Yukie’s Japanese rendering of the original, which is both a literary product in its own right and a text that has been widely read and recognized in Japan as a landmark of Ainu creativity and Ainu-Japanese cultural relations.

|

Chise, Ainu Home. From the Japan Focus Version, January 24, 2009. |

Preface to the Ainu Shin’yōshū (Ainu Songs of Gods) by Chiri Yukie

Long ago, this spacious Hokkaido was our ancestors’ space of freedom. Like innocent children, as they led their happy, leisurely lives embraced by beautiful, great nature. Truly, they were the beloved of nature; how blissful it must have been.

On land in winter, kicking the deep snow that covers forests and fields, stepping over mountain after mountain, unafraid of the cold that freezes heaven and earth, they hunt bear; at sea in summer, on the green waves where a cool breeze swims, accompanied by the songs of white seagulls, they float small boats like tree leaves on the water to fish all day; in flowering spring, while basking in the soft sun, they spend long days singing with perpetually warbling birds, collecting butterbur and sagebrush; in autumn of red leaves, through the stormy wind they divide the pampas grass with its budding ears, catch salmon till evening, and as fishing torches go out they dream beneath the full moon while deer call their companions in the valley. What a happy life this must have been. That realm of peace has passed; the dream shattered tens of years since, this land rapidly changing with mountains and fields transformed one by one into villages, villages into towns.

Nature unchanged from ancient times has faded before we realized it. And where are the many who used to live pleasurably in the fields and the mountains? The few of us Ainu who remain watch wide-eyed with surprise as the world advances. And from those eyes is lost the sparkle of the beautiful souls of the people of old, whose every move and motion were controlled by religious sentiment; our eyes are filled with anxiety, burning with complaints, too dulled and darkened to discern the way ahead so that we have to rely on others’ mercy. A wretched sight. The vanishing—that is our name; what a sad name we bear.

Long ago, our blissful ancestors would not for a moment have imagined that their native land would in future become so miserable.

Time flows ceaselessly, the world progresses without limit. If at some point, just two or three strong persons were to appear from among us, and, in the harsh arena of competition, expose what wreckage we have now become, the day would eventually come when we would keep pace with the advancing world. That is our truly earnest wish, what we pray for day and night.

But—the many words that our beloved ancestors used to communicate in their daily lives as they rose and as they lay, the many beautiful words they used to use and transmitted to us: would they also all disappear in vain together with the weak and vanishing? Oh, that is too pitiful and regrettable.

Having been born an Ainu and grown surrounded by the Ainu language, I have written down, with my clumsy pen, one or two very small pieces from the various tales that our ancestors enjoyed reciting on rainy evenings or snowy nights as they gathered at their leisure.

If many of you who know us read this book, on behalf of our ancestral people, I would consider it an infinite joy, a supreme blessing.

March 1, 1922

|

Owl and Child, From the Japan Focus Version, January 24, 2009. |

The Song the Owl God Himself Sang

“Silver droplets fall fall all around me

golden droplets fall fall all around me.” So singing

I went down along the river’s flow, above the human village.

As I looked down below

paupers of old have now become rich, while rich men of old

have now become paupers, it seems.

By the shore, human children are at play

with little toy bows with little toy arrows.1

“Silver droplets fall fall all around me

golden droplets fall fall all around me.” So singing

as I passed above the children

running beneath me

they said the following:

“A beautiful bird! A divine bird!

Now, shoot that bird,

the one who shoots it, who takes it first

is a true valiant, a true hero.”

So saying, children of paupers of old now rich

fixing to little golden bows little golden arrows

shot at me, but I let the little golden arrows

pass beneath me and pass above me.

Amongst them, amongst the children

one child carrying a plain little bow and plain little arrows

is mingling with the rest. As I look

a pauper’s child he seems, from his clothing, too,

it is clear. Yet a careful look at his eyes2

reveals that he is the offspring of a worthy person,

a bird of a different feather, he mingles with the rest.

To a plain little bow he fixes

a plain little arrow, he, too, aims at me.

Then the children of paupers of old now rich burst into laughter

and they say

“Oh, how ridiculous.3

A pauper child.

That bird, the divine bird

doesn’t even take our golden arrows.4 One like yours,

a pauper child’s plain arrow of rotten wood,

surely, he’ll take it all right.

That bird, the divine bird.”

So saying, they kicked and beat

the pauper child. Minding not a whit,

the pauper child aimed at me.

Seeing how it was, I was touched with pity.

“Silver droplets fall fall all around me

golden droplets fall fall all around me.” So singing

slowly in the big sky

I was making a large circle. The pauper child,

one foot far out and the other foot close by,

biting his lower lip, aiming while

letting it go. The little arrow flew

sparkling toward me, so I extended

my hand and took that little arrow.

Circling around and around

I whirled down through the whistling wind.

Then, those children ran toward me.

Stirring up a blizzard of sand, they raced.

The moment I fell to the ground,

the pauper child ran to me first and took me.

Then the children of paupers of old now rich

came running from behind him.

They said twenty bad things, thirty bad things

pushing and beating the pauper child:

“A hateful child, a pauper’s child.

What we tried to do first you did ahead of us!”

As they said this, the pauper child covered me

with his body, firmly holding me under his belly.

After trying and trying, finally from between people,

he leaped out, and ran and ran.

Children of paupers of old now rich

threw stones and splinters of wood at him, but

the pauper child, not minding a whit,

stirring up a blizzard of sand, ran and arrived

at the front of a little hut. The little child

placed me in the house through the honored window,

adding words to tell the story that it was thus and so.

An old couple from within the house

came out, each with a hand on his forehead,

and I saw that they were extremely poor. Yet

there were signs of a master, signs of a mistress.

Seeing me they bent themselves at the waist with surprise.

The old man fixed his sash

and made a ceremonial bow.

“Owl god, great god,

to the meager household of us paupers,

thank you for presenting yourself.

One who counted myself amongst the rich in bygone days,

now I am reduced to a humble pauper as you see.

I stand in awe of lodging you,

the god of the land,5 the great god,

but today the day has already dusked,

so this evening we will lodge you, the great god,

and tomorrow, with inau,6 if with nothing else,

we will send you, the great god, on your way.” So saying

he repeated his ceremonial bows over and over again.

The old woman, beneath the eastern window

laid a spread and seated me on it.

And then the moment they lay down,

with snores they fell fast asleep.

Seated between ear and ear of my body7

I remained, but not too long after that, around midnight,

I rose.

“Silver droplets fall fall all around me

golden droplets fall fall all around me.”

Thus singing quietly,

to the left seat, to the right seat,8 within the house I flew

making beautiful sounds.

When I fluttered my wings, around me

beautiful treasures, divine treasures scattered down

making beautiful sounds.

Within a short while, I filled this tiny house

with wonderful treasures, divine treasures.

“Silver droplets fall fall around me

golden droplets fall fall around me.”

So singing, I changed this tiny house

in a moment into a golden house, a large house.

In the house I made a fine treasure altar,

hastily made fine beautiful garments, and

decorated the interior of the house.

Far more finely than for the residence of the rich,

I decorated the interior of this large house.

That done, I sat, as before,

between ear and ear of my helmet.9

I made the people of the house have a dream:

Ainunishpa10 unluckily became a pauper,

and by paupers of old now rich

was ridiculed and bullied. Which I saw

and took pity on, so although I am not a plain god

of meager status, I lodged

at a human’s house and made him rich.

This I let them know.

That done, a little while later when it dawned,

the people of the house rose all together.

Rubbing their eyes, they looked around the house

and all fell on the floor, having lost feeling in their legs.

The old woman cried loudly.

The old man shed large teardrops.

But before long, the old man rose,

came to me, ceremoniously bowed

twenty times, thirty times in repetition, and said,

“A mere dream, a mere sleep I thought I had,

but what wonder to see your blessings in reality.

To our humble, humble11 meager house

you have come, and for that alone I am thankful.

The kotan god, the great god

pities our misfortune,

and, behold,12 the most precious of blessings

you have given us.” Thus through tears

he spoke.

Then, the old man cut an inau tree,

beautifully carved a fine inau, and decorated me.

The old woman dressed up.

With the little child’s help, she gathered firewood,

scooped water, prepared to brew wine, and in a little while

arranged six vats at the seat of honor.

And then, with the old woman of fire,13 the old female god,

I exchanged stories of various gods.14

In two days or so, wine being the gods’ favorite,

inside the house the fragrance

already wafted.

Now, the child, deliberately clad in old clothes

to invite from throughout the village15

the paupers of old now rich,

was sent off on an errand.

As I saw him from behind, entering each house,

the child delivered the message he had been sent,

at which the paupers of old now rich

burst into laughter:

“This is strange, those paupers.

What wine they brew.

What feast they invite people for.

Let’s go and see what’s there

and have a big laugh.” So saying

to one another, many of them together came,

and from a long distance, at the mere sight of the house,

some went back startled and embarrassed,

while others fell to the ground upon reaching the house.

Then, as the lady of the house went outside to

take all by the hand and usher them inside,

all crawled and sidled,

none raising his head.

Upon this, the master of the house rose and

spoke in a sonorous voice like a cuckoo’s.16

Thus and so, he said, was the situation:

“Like this, being paupers, without reservation,

to keep company with you was beyond us,

but the great god took pity.

No evil thoughts did we ever entertain,

and so in this manner we have been blessed.

From now on throughout the village we will be a family.

So, let’s be friends

and keep company—to you

I convey this wish.” Thus

he spoke. Whereupon the people,

time and time again, rubbed their palms together,

apologizing to the master of the house for their wrongs.

From now on they would be friends, they said to one another.

I, too, received ceremonial bows.

That done, their hearts mellowing,

they held a cheerful banquet.

With the god of fire, the god of the house,17

and the god of the altar,18 I spoke,

while the humans danced and stepped,

a sight that deeply amused me.

Two days passed, three days passed, and the banquet ended.

The humans made good friends,

seeing this, I felt relieved, and

to the God of fire, the god of the house,

and the god of the altar I bade farewell.

That done, I returned to my house.

Before I arrived, my house had been

filled with beautiful inau and beautiful wine.

So, to nearby gods and distant gods,

I sent a messenger to invite them to a cheerful banquet

I was holding. At the party, to those gods,

I spoke in detail of how, when I visited a human village,

I found its appearances and circumstances.

Upon which the gods praised me highly.

When the gods were leaving, beautiful inau

were my gifts, two of them, three of them.

When I look toward that Ainu village,

now peaceful, the humans are

all good friends, that nishipa

being the village head.

His child, now having become

a man, has a wife, has a child,

is filial to his father, to his mother.

Always, always, when he brews wine,

at the start of a banquet, he sends me inau and wine.

I too sit behind the humans

at all times

as I guard the human land.

Thus the owl god told his tale.

Chiri Yukie’s preface and poem “Kamuichikap kamui yaieyukar, ‘Shirokanipe ranran pishkan’” (The Song the Owl God Himself Sang. “Silver Droplets Fall Fall All Around.”) were originally published in Ainu shin’yōshū (Ainu Songs of Gods) (Tokyo: Kyōdo Kenkyūsha, 1923). This translation was first published as Chiri Yukie and Kyoko Selden, “The Song the Owl God Himself Sang. ‘Silver Droplets Fall Fall All Around,’ An Ainu Tale,” The Asia-Pacific Journal. Volume 4-5-09. January 24, 2009.

Notes

In bygone days, adults made small bows and arrows for young boys. While enjoying shooting at trees and birds, before they knew it, the boys became skilled archers. In the Ainu word “akshinotponku,” “ak” means archery, “shinbot” play, and “ponai” a little arrow.

shiktumorke: a look. When trying to learn a person’s true nature, the best way is said to be to look at the eyes. People can be scolded for looking about restlessly.

It is said that, when birds and beasts are shot down, they take the arrows because they want human-made arrows.

kotankorkamui: god of the land or the village. In the mountains, there are nupurikorkamui, the god who has the mountain (bear); nupuripakorkamui, the god who has the east side of the mountain (wolf); and so forth. The owl is placed next to the bear and the wolf in the taxonomy. Kotankorkamui is not wild and hasty, as is the god of the mountains and the god of the eastern mountains. Instead, he is usually calm and keeps his eyes closed. It is that he only opens his eyes when serious events occur.

Chiri Mashiho explains in a footnote to his translation that, when the owl god was seated on the patterned mat beneath the honored window, its spirit was believed to reside between its ears (Hanazaki, Shimajima wa hanazuna (Garland of Islands), Tokyo: Shakai hyōronsha, 1990), 113.

There is a fire pit at the center of the house. The side against the eastern window is the seat of honor. Looked at from the seat of honor, the right is “eshiso” and the left is “harkiso”. Only men can take the seat of honor. A visitor who is humbler than the master of the house refrains from taking this seat. The master of the house and his wife always take the right seats. Next in importance are the left seats, while the western seats (near the entrance) are the most humble.

hayokpe: armor. While in the mountains, although invisible to the human eye, both birds and beasts have houses that resemble those of humans, and they lead their lives in the same ways as humans do. When visiting a human village, they are said to appear in armor. Their true forms, although invisible, are said to dwell between the ears of the heads of the corpses.

nishpa, now spelled “nispa,” signifies a well-to-do man, a wealthy man of high status, or a master. The antonym is “wenkur,” or pauper.

otuipe: one with its tail cut short. (Annotating the phrase wenash shiri otuiash shiri.) A dog tail so short that it looks cut off is not much respected. An unworthy human is badmouthed as “wenpe,” a bad fellow, or as an otuipe.

chikashnukar is when a god unexpectedly graces a human with a great fortune. The human then responds in delight “ikashnukar an.”

apehuchi: the old woman of fire. The god of fire, the most important of the household deities, is always an old woman. When gods of the mountains, the sea, and so forth visit a house, as does this owl god, the apehuchi takes the lead in conversing with them. It is also acceptable to call her “kamuihuchi” (divine old woman).

neusar: chatting. While worldly rumor is also called neusar, the term usually refers to such things as kamuiyukar (songs of gods) and uepeker (old tales).

ashke a uk (from “ashke,” for fingers or hand, and “a uk,” meaning to take): inviting people for a celebration or other festive event.

kakkokhau: cuckoo’s voice. Because a cuckoo’s voice is beautiful and clear, one who articulates so that everyone can understand is likened to the bird.

chisekorcakui: the god who owns the house. The god of fire is like the housewife, the god of the house like the master. The god of the house is a male and is also called “chisekorekashi,” literally, the old man who owns the house.

nusakorkamui: the god of the altar, who is an old woman. The god is always female. When something bad happens, she may appear before humans in the form of a snake. Thus when a snake appears near the altar or near the eastern window, people say, “Perhaps the old woman of the altar went out on some business,” and they never kill the snake. It is said killing the snake will cost a human dearly.