|

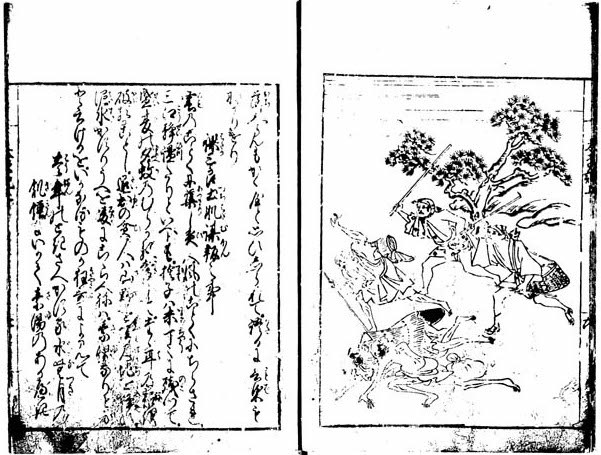

Illustration from the Hinin Taiheiki, 1688 edition. Scanned online at University of Tokyo Digital Library. |

Indeed, a single laugh can expel a hundred depressions. In this world, however, there is nothing novel in recounting the same ordinary facts. Tosa Shōgen1 provoked laughter by painting a farting battle. Inspired by his example, I now record the battles of the beggars and the paupers, titling my account Hinin Taiheiki. Naturally, the characters are but warriors astride their own two legs—bare as a bare dapple-grey horse, yet worth one hundred kan.2 They carry iron hooks, though rusted, and wear armor of straw mats, though torn. May they be a source of laughter for all those who observe them.

The ninth month, the fifth year of Jōkyō [1688]

Table of Contents

Chapter I

The First Laugh of the Year: Droves of Paupers

The Debauchery of Kawashima Dwellunder, the Governor of Ima Bridge

Third-Born Son Bareman Saburō Dirtskin Rises in Rebellion

Kōzu Castle: Nakamura Kyūan Writes a Supplication3

Paupers From Various Places Rise Up

Chapter II

The Chiefs Gather Forces: They Attack the Paupers4

One-On-One Combat at Gokuraku Bridge: The All-Out Battle

Tokinosuke’s Death in Battle: Lady Begging Bowl’s Grief

Chapter III

Seedless Exits the Castle and Attacks Kōzu: Lady Wheel

Startled by a Stick, Dōgan Composes a Great Poem: He Is Scared Out of His Wits by a Dragon Head

A Deaf Monk Dies and Revives: Paupers and Beggars Enjoy Prosperity

Chapter I

The First Laugh of the Year: Droves of Paupers

Po I and Shu Ch’i who disdained worldly pleasures, even as they were dying of hunger, and, exhibiting great mental resolve, left for posterity names of great renown. The poor of this realm once fought over victuals and started a war.

Well now, let me tell you how, in the summer of the ninth year of Enpō [1681], the war between the paupers and the beggars began. In the famine of the third year of Enpō [1675], the paupers had escaped almost certain death. Just a few years later [in 1681], a great wind arose across the land, and the rain bore down like spokes of a wheel, gouging holes in the fields. Floods long hid the mountains. The people lamented: “The Three Great Calamities have finally brought destruction and nothingness, and the Twenty Cycles of increase and decrease have reached their final phase.”5 Sure enough, the great famine reached its peak the following spring. There was no food at all. However, the bay of Osaka in Settsu province, Japan’s largest port, was full of rice. A mountain of 100,000 bags of rice and grains filled the ten directions and reached to the Big Dipper; white clouds hung around its slopes, and migrating wild geese bumped into it in confusion.6

Thus paupers from all the provinces, seeking relief from hunger and thirst, arrived in Osaka. In district upon district, streets and alleys teemed with paupers; there was not even space for the usual traffic. Paupers surrounded houses on the left and right, raising a clamor, like a confusion of rice seedlings, flax, bamboo, and reeds,7 and begged until the heavens echoed and the earth shook. Such misery! People, who until yesterday would never have been seen standing before the doors of others, now urged on their weakening bodies and wandered away from their homes, leaving their parents and abandoning their children. Those unable to abandon their families walked with them, hand in hand, letting their pitiful babies cry, or used their aging mothers as a means to beg for scraps. Or they parted from loved ones so that each could wander from place to place, near and far, begging, all the while becoming weaker. Like the Amida Buddha during his five kalpa meditations, pale bumps changed their countenances so much that they did not recognize one another when they met on the road.8 Familial and kinship ties were broken. And there were many who thought putting out their hand to seek help to be too mortifying, preferring instead to drown themselves and vanish. Of course, “even the prosperous are bound to decline.”9 People nevertheless wondered at the fresh sorrows this year had brought.

Moreover, starving paupers who could not finish the long journey lay on the mountain roads and on the paths through fields. Gasping, dying on the dew-laden grass—who knows how many thousands and tens of thousands crowded the eastern and western provinces.

The Debauchery of Kawashima Dwellunder, the Governor of Ima Bridge10

On high are government officials; below among the lowly are the headmen. These are the generals of the beggars: Homeless of Tobita, Bamboo Fence of Dōtonbori, Single Chopstick of Tennōji, and Seedless of Yoshiwara in Tenma.11 Since the founding of Osaka, for generations on end, the men who inherited these names and positions have been looked up to as Shoguns of the Begging Bowl.12 And not only in Osaka—in provinces far and near, organized beggars respected them as bosses. Becoming proud, these chiefs forgot their lowly status, sated themselves with abundant food, and indulged in great extravagance. Both day and night, they had their subordinates, on or off duty, report to them and attend their office. Here and there, the chiefs established outposts and assigned on-duty beggars to districts as they thought appropriate.13 Furthermore—whether at charity food stalls, regular morning meals, or afternoon snacks—these chiefs robbed lesser beggars of their food as they pleased.

The paupers, who had traveled from various provinces, felt that even “under the trusted tree they found no protection from the rain.”14 Having exhausted their daily sustenance, they miserably gathered common greens.

Even worse, the chiefs met in assembly and said, “This place is packed with paupers. We must drive them out of our domains.” All agreed, and Kawashima Dwellunder, Governor of Ima Bridge, taking three hundred select young men, voracious and fierce, drove out the mass of paupers as if they weren’t human beings at all. The paupers stumbled about in great confusion, their begging bowls struck down, and fled in all directions. Those with weak legs and hips fell on top of one another, and, although some tried to stand together, with their stomachs empty, their legs would not respond. All they could put to use were their eyes. Hardly able to breathe, they shrieked and howled. One would think that sinners in Hell, whipped by jailer demons and cast down into molten iron, would be just like these paupers. Truly, there are no words to describe this scene.15

Third-Born Son Bareman Saburō Dirtskin Rises in Rebellion

Paupers who had gathered like clouds were scattered like the wind; although Osaka’s three rivers were calm, its various streets teemed with abandoned children,16 their whining, like mosquitoes swarming on a mid-summer evening, threatening to burst people’s eardrums. Paupers driven out of Osaka now filled the mountains and fields, and even as they fought for a little space, they couldn’t possibly slake their hunger by sipping muddy water. They begged—if only for plain boiled water. Someone composed a satirical poem:

Even in a bumper year, there’s little water to sip in the sixth month17

In time of famine how can there be hot water?

The number of those who, even without wounds and illnesses, still fell dead mornings and evenings increased by the day until they were impossible to count. Corpses lay everywhere, leaving no space to set foot. Even so, paupers gathered from throughout Japan and a great many survived.

Now, there was a man called Bareman Saburō Dirtskin. Born in Kantō, he lived on the scraps of the lowest samurai servants. But poverty hounded him, and, to avoid the famine, he had come to Osaka around mid-spring and become a pauper.18 His hometown revealed itself in his appearance: he was tall and dark-skinned, his hair never bound and his beard overgrown to the left and right.19 His eyes were sunk deep, and his backbone touched his belly; yet he was stout of mind and of outstanding strength. Bareman Saburō Dirtskin looked as Shōki would when confronted by famine.20 He was a valiant man with an iron gaff who looked no whit inferior to Fan K’uai in rage and would pick up Chang Liang’s book of military strategy only to trash it.21 But even a man like that had to bend to the ways of the world—like a tiger subordinated to a mouse—and thus he dwelled humbly on the outskirts of the city.

Now Bareman Saburō Dirtskin secretly gathered together the paupers and said: “Even the supply of burnt rice gruel is already gone,22 and our lives, transient like the dew, are about to end. Frustration and resentment from one life are hard to overcome in the next. We are going to die anyway. So friends, if we make Kōzu our fortress and rise in mutiny,23 many will join us as allies. What say you, gentlemen?”

At this point, two men, Yazō the Rice Chewer and Worn Heels,24 came forward and said, “It is as you say, sir. Paupers would climb up to heaven or enter the spring of the underworld to show our grievances; not one of us will disobey you. Do not tarry a moment, but make up your mind.” And so, all present united, over eight hundred in total. The weak-legged taking up walking sticks and the lame carried on the backs of the strong, they moved to Kōzu and barricaded themselves on the evening of the twentieth day of the sixth month.

Kōzu Castle: Nakamura Kyūan Writes a Supplication

The paupers, who until yesterday had felt hesitant and fearful when gathered, gained the force of a dragon and fortified the castle of Kōzu, as if thunder raged overhead while they trod on blades below. The place itself was a strong mountain citadel with a profusion of huge trees. The paupers sought out places of shelter from the rain; they then constructed an underground water pipe at the bottom of the valley and brought from Kōnoike warriors drinking water that was used for rinsing sake bags.25 In the surrounding fields they cut assorted plants, field horsetails, and summer grasses down to the roots so that not even a single leaf remained. Skilled swimmers went to the offing at Kotsuma and Nagai, and in no time at all, brought back several thousand loads of seaweed.26 There were great heaps of bran and mountains of tea dregs. Although they had none of the five standard grains, there would be no worries at least until the time when they again scooped steamed wine rice.27 They thought of all the details as they planned far into the future. So clever was Bareman Saburō Dirtskin.

Cliffs rose high to the east and west, and the paupers’ straw mats stood like many screens.28 To the north was the sacred hall, protected by the precipitous slope behind it and the eye-stinging smoke from baking roof slates.29 There was no hope for anyone wanting to climb up that way. They decided to make the south the main front. At night they stole stupa grave markers to use as blockades and thorny barriers.30 They let flags of torn straw mats stream in the gale that blew through the pines and further hoisted more mats in the clearings in the woods so that it appeared as if there were several tens of thousands of soldiers.

Bareman Saburō Dirtskin summoned Nakamura Kyūan and said to him: “It is sacrilegious that we paupers defile the shrine with our presence. For this reason and for the sake of praying for our military fortune, write a supplication and offer it to the shrine.”31

Kyūan obeyed immediately and taking up his worn brush, wrote:

Enshrined in this hall is Emperor Nintoku, who, in his reign, soothed the grief of all, demonstrating the depth of his mercy, which surpassed even that of Emperors Jinmu, Daigo, and Murakami.32 For this reason, the land was fertile, and there was not one pauper. But in later days, many of the lowly have been distressed by frequent famines. We paupers were eking out a living when the four beggar bosses obstructed our efforts to get food, and so we have even less to eat. The blame lies solely with the barbarians on the four sides.33 Half-dead, starved people fall everywhere, and there is no place to step. Wishing to avenge ourselves, we have raised these soldiers in the cause of justice. Yet for us small eaters to fight those big eaters is like breaking an iron wall with chopsticks or draining water from the great ocean with a begging bowl. It is not that just because I have descended to paupery, this Heaven-endowed self is beyond humanity. Prostrate, I beg that your divine power extend mercy, secure our immediate victory, and bring about an era of rich harvests. Thus we present our supplication.

Kyūan placed the writing in the sacred hall along with the first-crop offering that he held in his hand.34 Because the gods illuminate the truth of those who are honest, they must have seen Bareman Saburō Dirtskin’s heart. Mysteriously, from a pine branch in front of the sacred hall, a poetry card rode a gust of wind and fell before him.35 He picked it up and found a satirical poem on it:

Climbing the Palace of Kōzu,36 I see flags hoisted:

Pauper forces are thriving.

“Behold what the Deity has given us!”

This poem alludes to the felicitous poem Emperor Nintoku in his wisdom composed during his peaceful reign:

Climbing a tall turret, I see wisps of smoke rise:

People’s cooking stoves are thriving.37

“The emperor deity turned this into a satirical poem to encourage us.” So saying, those present took off their cheek covers, bowed nine times, and performed a vigil that night.38

Paupers From Various Places Rise Up

In the early morning of the twenty-second, the next day, from the blackness of Ikutama Forest came shivering a force five-hundred combatants strong.39 Thinking that the enemy was approaching, the men were alarmed; but then from amidst that force, one warrior, who had scratched himself until his skin was white, with a begging-bowl helmet and armor woven of scabies with long hems,40 stood tall before the front gate, and in a hoarse voice announced: “These are the inhabitants of the Lower Temple District, an area of Buddhist temples. Our faces are oft exposed at each equinoctial service at the temples, and thus we are known even to the masters who travel down from the capital to pay their respects. With us are the paupers of Kizu, Imamiya, and Abeno.41 They have all come together as allies!”

Bareman Saburō Dirtskin ordered the wooden door opened to let them in.

That was not all. The paupers of Enami, Hakke, Hirano, Kyōbashi, and Amijima all gathered in force in front of Daichōji Temple and joined as allies.42 Then the pauper troops filled the castle completely, until there was not even room for them to put down their begging bowls.

Again, in the vicinity of Tenma, the paupers of Kitano, Dōjima, Noda, and Fukushima came together and,43 with Kyūzō the Companion Robber as general, before sunrise they pressed forward to the water’s edge at Chōja,44 smashing their earthen ovens and earthen pots, their momentum tremendous. They then continued on to Yoshiwara in an immense show of strength.45 Hearing rumors of their advance, Osaka’s beggar chiefs and their subordinates met in conference to decide what to do. Homeless of Tobita came late and said: “We might not know what to do, sir, if they were a force attacking from China or India. But these are the same men we cleared out of here the other day. And they have been wandering the mountains and are probably exhausted from scrounging for food. How much can they do? When torches sputter out, they flare up. The paupers can’t be far from self-destruction. Even so, if we leave them alone, they will disturb our food supply—especially since today is the Ikasuri Shrine Festival, and the twenty-fifth is the Tenman Festival.46 How can we ignore these dates when we do such good business at the gates of those festivals? How can we let these paupers hold us back? The day after the Tenman Festival, let’s drive them a thousand ri away and make this a world where the crane lives a thousand years and the tortoise ten thousand.47 What complications could there be?”

Since he spoke as if the matter was of little concern, everyone agreed, and they dispersed, only to find that the postponement to a later day had proven fatal. Day by day, the paupers grew in strength and in the end equaled their enemy. This situation exemplified the saying “A cornered mouse bites the cat.”48

Chapter II

The Chiefs Gather Forces: They Attack the Paupers

On the twenty-sixth day of the sixth month, the chiefs collected their forces in front of the Chikurinji Temple and inspected the ranks.49 Their beggar troops had gathered from Ferry, Long Moat, Inner District, and Long District50—sixty-eight thousand in all. Standing tall with their legs spread and holding iron hooks horizontally, they resembled people in a ten-thousand-sutra incantation at an alms-giving ceremony. The three bosses were attired identically: each fully turned out in a five-tiered helmet of scoops stacked together, loosely wearing great armor sewn together from tattered cloths and with hems torn,51 a coarse braided rope to tie it all firmly, a sardine-drying mat as a belly band, and squash rinds for hand and shin protection. For arrows they carried unlacquered chopsticks used for dyeing teeth, long enough that the arrowheads showed from their quivers.52 Each under his left arm held, as an iron hook, an eight-inch nail forged by the impoverished blacksmith Sanzō attached to a five-foot-three-inch awl they called Iwakuni, sharp enough to penetrate cardboard.53 Thus arrayed they divided their forces.

The Single Chopstick vanguard took the Tennōji force of seventeen thousand men to the Upper Temple District; Bamboo Fence took twenty-five thousand men down the slope of Ikutama and pressed to the main front.54 The homeless fortified the rear, pressing on toward the Nun Slope of Takahara.55 As the forces raised their beggars’ cry,56 heaven and earth shook from all three sides until the lice almost fell to the ground dead.

The paupers in the castle, however, did not shoot even a single chopstick; nor was there any sign of confusion. By nature, Bareman Saburō Dirtskin was never alarmed in a crisis. Thoughtful and cunning, and having learned Sun Ch’en’s secret art of wearing straw mats,57 he made fending off the cold his first strategy. Thus keeping the castle hushed, he made it look as if nobody was inside.58

“Judging from the appearance of this castle,” the beggar general Bamboo Fence said to his allies, “It doesn’t seem that the enemy force barricaded within is very large at all. Hearing that we were approaching, those ragtag paupers must have fled. Even if some remained to defend the place, they haven’t eaten and are not likely to be firm of leg and hip. Tear away the castle gate and those abatises. Break in! Break in!”59

At this command, the main and rear forces united, lined up the tips of their metal hooks, and tried to bring down the barricades. Just then, from within the castle, fish bones poured down like rain.60 As the great attacking army stepped on them and hesitated, the paupers within the castle dashed out, brandishing their blades and fighting as if this were their last battle.61 Beggars in the front tripped; unable to fight, try as they might, many were killed. Men in the rear dropped their begging bowls and metal hooks and retreated as quickly as possible. Since the paupers were empty-stomached, they did not press their advantage and chase their enemy. Having won the first battle, they returned to the castle.

The chiefs gathered the stragglers and said, “So many of our troops were killed by the enemy’s unexpected strategy because we attacked barefoot. For tomorrow’s battle we’ll prepare footwear and crush the castle in one attack!” They fumed.

At dawn the next day, beggars attacked the castle like locusts. Having been surprised by the fish bones the day before, the chiefs had everyone wear sandals with leather soles. They gave orders in concert: “Break fish bones under your feet, be they the sharpest bones of bream! Attack! Attack!” Eager to avenge yesterday’s defeat, many raced forward.62

When the castle appeared to be in danger from the advance, the paupers tore open several hundred bags full of squash pulp from inside the castle walls where they had stored them.63 The forces that had climbed all the way up slipped on their leather-soled sandals. They had nothing to hold onto. All at once they fell, and, with no place to secure their footing, they slid down. Beggars waiting in the rear for clean-up duty cried, “Leave it to us!” They took up their bamboo brooms and, changing places with the advance troops, swept away the pulp. Now, with their forces combined, victory seemed theirs at last. But then the paupers opened the gate and showered them with stone lanterns in front of the shrine hall. So many dropped fast, to the right and to the left. Sparks flew, reverberating like hundreds and thousands of thunderbolts. Several tens of thousands of beggars were pushed and dropped to the bottom of the valley. Crushed under the weight of stones, they were, it seemed, pressed sushi of beggars.64 You might say Yashima, but, no, truly, it must have been just like the Battle of Tonami during the Minamoto-Taira War, in which the Taira warriors were thrown into the valley of Kurikara.65 At that battle, Heisenji’s chief was killed,66 but in this battle, the chiefs survived and retreated to Tairenji Temple.67

One-On-One Combat at Gokuraku Bridge: The All-Out Battle

When the news got around that the chiefs had lost, the troops waiting at Shoman, Kōshindō, and Komachi-zuka, three thousand five hundred men at Oriono, and two thousand at Sumiyoshi Shinke, rushed to Tairenji without delay and lined up along the Genshōji Slope.68 However, since the chiefs, having lost a great many men in the two battles, seemed reluctant to make another advance, the morale of the reinforcements dropped, and they, too, dawdled. The pauper troops, on the other hand, spurred by victory, dashed out to Shinyashiki on the other side of Paradise Bridge.69 The rear guard made a ruckus at the Motomachi Bridge crossing.

As both camps stared across at each other, from the beggars’ side came a warrior who looked like a mounted knight equal to a thousand men. In a five-tiered helmet of brightly shining watermelon rinds and body armor of a thousand rags sewn together, he advanced to Bareman Saburō Dirtskin. “Do you know this warrior who has now come before you?” he asked. “Following the steps of Liu Pai-lin,70 I enjoy sake dregs, make all eight corners of the world my lodging, follow no rut where I wend, and, having no abode for a dwelling, I stay when and where I like. Thus people recognize me as Rokuzō-before-Kontaiji Temple.71 If there’s a man who dares to match me, let him come forth and witness my prowess.” And he waited calmly.

Then from the paupers’ side came forth a warrior, also appearing to be of great strength, with dust for an ornament on his helmet of white hair, itchy scabs for hand guards, tumors for shin protection, and thigh guards that were sandalwood in color. He proclaimed before all: “Although it may bring shame to my clan for me to reveal my ancestors, what should I be ashamed of here? I am a one-life-in-ten-deaths descendant of Courtier Waterbelly of the water that Hsü Yu scooped in his hands to drink.72 Discarded by the five grains for so long, we have stooped low. I am the second generation of famine. Advance, I’ll grapple with any of you!” The two warriors tottered together until both fell to the dirt and alas breathed their last.

Friend and foe alike were touched to witness this sight, but, in no time, there came from the beggars’ side a warrior with a helmet of ferns that hung long over his shoulders, a helmet decoration of yuzuriha twigs, and cheek covers made from a red washcloth.73 Although it was not yet the end of the year, he advanced dancing and said: “I am the next warrior, and I do not fear death. I am a warrior, and you should know me even if I do not introduce myself. I am Sekizoronosuke, famous throughout the world starting around the twentieth day of the spring-waiting sky.74 Blessings, blessings, come forward and fight!”75 He beckoned his enemy and waited.

Then, from the paupers’ side came a warrior with disheveled red hair and mud-covered feet on which no one knows how long he had traveled;76 he walked out leaning on a bamboo staff: “Since I am not numbered among the great, you would not know me even if I introduced myself. Never in my life have I had a place to settle. I may be here or wander elsewhere. Sometimes I grab sweet dumplings or toasted rice cakes and run, so I am called Kiteman.77 Other times I eat the intestines of poisonous fish without suffering the poison, and I have the glory of remaining alive. Today, however, is the last day of my life.” So saying, he died on the spot.

“What an unworthy death,” said a pauper waiting in the rear. Advancing through the pauper ranks, he bellowed: “Those who are far should listen with their ears, and those who are near should see with their eyes.78 Make your model the work of this man of great strength whose ribs remember the feel of the cane from repeated thieving.”79 With this he leaped at Sekizoronosuke.

Sekizoronosuke, ready for combat, shouted, “Advance!” He swung his rice bag and fought, now charging and now dodging. “Don’t let this one get beaten” and “Don’t let that one get beaten,” the men shouted, as enemies and friends pressed together on top of one another in a melee.

Bareman Saburō Dirtskin ran in all four directions giving orders: “Watch out! Don’t kill your friends! Men with wooden tablets on their waist are your enemies.80 Kill them.” Since paupers by nature place great weight on food and give little weight to their lives, not even considering surviving another winter, they did not retreat a step. But stepping and leaping over the dead, they fought fiercely, tore begging bowls asunder, fiery sparks flying from their metal hooks, and pursued the enemy as if this were their final battle. Then the beggar troops, reduced to a meager size, straggled southward. The paupers let out victory cries and returned to their castle.

Accumulated vice always brings decline. Almost all who had wickedly and licentiously stolen food were killed, and the paupers were elated. They had repelled great forces in repeated battles, all due to Bareman Saburō Dirtskin’s excellent planning. Long ago a great king of China loved his multitudinous subjects and ruled his great country. However, people from all four foreign and eight barbarian tribes arose, and the king’s forces were destroyed. “I alone should not escape,” the king said. He was about to commit suicide when a wise man called Chang-tze, who had remained behind, remonstrated with him. He took the king to a neighboring state and waited for an auspicious time. Among the paupers of that state was a valiant warrior by the name of En Mao who built a castle for the king. The king raised a large force, enjoyed his second bout of luck, and returned to his home state. People were moved by Bareman Saburō Dirtskin’s work at these battles as they recalled this story.

Tokinosuke’s Death in Battle: Lady Begging Bowl’s Grief

Among the heads taken in battle, inspected by Bareman Saburō Dirtskin and posted on the gate, was that of Tokinosuke,81 a fine young man who stood out even among the ranks of the beggar chiefs. Excelling in literary pursuits as well as martial arts, he had traveled far along the path of fine sentiments. Nevertheless, he had been killed in no time, his head, too, displayed.

Here, now, is a sad story.

Out of nowhere a woman approached. Taking one look at Tokinosuke’s head, she collapsed on the spot. “Is our karmic link so weak,” she wailed, weeping so hard that it was unbearable to look upon her. After a while, suppressing her tears with a well-worn sleeve, she stole the head, put it in a cloth bag, and went where her feet led her:82

The first winds of autumn pierce body and soul

The bell tolls the impermanence of all

This expresses none other than my condition as I walk through the Upper Temple District.83

In this transient world where I live in a hut held up by bamboo poles

I am never far from rush matting84

The smoke of the burning house scorches the roof tiles.

Longing for the final prayer at the Pine House District

When will the boat of salvation arrive at the Ferry Crossing?

And what of the three evils of this short-lived world85

that create a sad obstruction at the Tenth Ward.

Though the compassionate light shines86

from on high before the shrine

Not knowing whether it is light or dark

A blind man wanders near the gate.

Must be one of us, he grieves, saying:

“From whence comes this karmic retribution?”

Let me compare my thoughts to his.

My grief is over the disappearance of my husband

Our pledge of love unto the next life meant nothing

Won’t you have compassion

For my future of sorrow that begins today?

Please help me, merciful people.

She passes by Daikyūji Temple as she prays.

On to the district of the He-and-She Ponds,

Hearing the name of whom her thoughts proliferate.

With tears, she came at last to the vicinity of the Tenman Shrine. There she visited a priest known as the Abbot of the Empty Stomach Temple of Mount No Food—a rare blessing to the world, a reincarnation of a pale shadow of Shakyamuni out from Vulture Peak—and asked him to officiate at the memorial rites for Tokinosuke. Then she prepared rinds of pear and persimmon in great amounts as food for the spirit. The priest stepped forward and recited this eulogy:

When you think of it, during his lifetime, a beggar lives beneath the starry frosty sky, his skin tortured by wind, rain, and snow. Although he does not suffer the trials of fire and theft at his house of the three worlds, absence of these is also painful. As hunger and thirst disturb his dreams, he rises without ado; running from east to west, hurrying north and south, he raises his voice in the morning, and when he gets no food begging, he gasps for breath in the evening, just like a fish in shallow water. What pleasure is there being in this world? Truly the beggar who passed beyond this defiled earth was just twenty-three, although years had piled up on him. Ah, what a blessing is a short life! He swiftly went to the office of Enma and was eaten by a demon’s single gulp….87

And so spoke the priest. Then he joined his hands and chanted, “Namu Amida butsu, Namu Amida butsu,” and the wife also prayed for the departed soul. Then, she gathered up the staves of her pail and, with a single puff of smoke, disappeared.

Now this woman was the daughter of Lord Bridge End and was called the Lady of the Begging Bowl. There was no limit to her father’s affection for her, and upon becoming an adult, she would certainly have married into the highest rank. However, those who meet must always part, and when this princess was an infant, both her father and mother died of starvation. An orphan, she was just barely able to live thanks to the mercy of the honored cook,88 and passed her days on leftover food. This year had seen her turn sixteen, and she was truly regal. Her red hair, longer than her height, played around the calluses on her heels as it swayed like a willow in the wind.89 Clad in tatters, it was hard to imagine anyone like her. Last spring at the time of flowering and lice viewing,90 Tokinosuke caught sight of her as she was out taking the sun. Love-sickness seared his heart and, unable to stop thinking of her, he secretly sent her a letter with this poem:

My love is thwarted at the barrier of the Chinese Comb91

Thoughts of you as numerous as hatching larvae.

As she was not a heartless rock or tree, they lay their pillows together on a bed of dirt and appeared to make pledges to grow old together and never part. But before long he left for the battlefield only to be killed. Everyone thought it was natural that she should grieve.

In the end, according to what people later said, she threw herself into the Nagara River. Even while we say that each life is forgotten in the next, still, one determined purpose lasts five hundred lives and a binding vow goes on indefinitely. So, she will probably continue to beg with the same thoughts, even to the lowest depths of hell. What a moving thought!

Chapter III

Seedless Exits the Castle and Attacks Kōzu; Lady Wheel

Well now, the paupers of Kitano, Dōjima, Noda, and Fukushima pressed toward Yoshiwara and attacked. However, the fortification was strong, and they could only stand and contemplate the castle. The citadel of Yoshiwara was bordered on the left and right by the He and She Ponds, and to the east and west ran canals and a stone embankment; the main road was little more than four yards wide. As the road was so narrow, it was extremely difficult to engage in a full-force fight. The water’s edge was swampy, and the stubble of the reeds like planted sword blades. In the middle of the water the waves rose high, and an old blue catfish, the master of the river, gobbled up those who fell in. Because of these perils, crossing there, too, was not possible.

As paupers began to advance along the main road, ready for one-on-one combat, beggars emerged from the shade of the sandalwood trees. Surrounding the paupers to the north and south, the beggars drove them into the ponds to the right and left. Feeling as though they were on the white road between two rivers, the paupers withdrew to the far end of the canal.92

Seedless, the beggar-general of the castle, called to Gateway Rokurō:93 “The enemies at the fortress of Kōzu are strong, and now that the Osaka beggar chiefs have been defeated, we are the only ones left for them to attack. Although this fortress is strong, it is hard to defend with such a small force. I hear that the bandits of Yamada, Saidera, Suita, Katayama, Harada, Tarumi, and Sanbōji have not joined the paupers at Kōzu and that they harbor no hatred toward the beggar chiefs.94 Morning and evening, they just hang about and eat melons and eggplants without permission, plunder daikon radishes, and eat the unroasted peas that are unworthy of being shot from guns.95 I wish to invite these men and give them license tablets, so they will become our allies. Put this plan into effect.”

Receiving this command, Gateway spread the news everywhere. Just as Seedless had anticipated, the bandits gathered like clouds and mist, everyone trying to be the first to join him. Seedless’s joy was boundless. “With a force like this there is no need for us to hide in the castle. Let’s advance and attack Kōzu!”

And so he gathered more troops: Nagara, Kokubunji, Honjō, Sanban, Mitsuya, Jūsan, and Imazaike96—a staggering number in total. In addition, there were leper well-wishers and exorcists.97 Fifty-eight thousand warriors in all. On the tenth day of the seventh month, they constructed a site for holding a memorial service for the unburied dead and, raising aloft the funerary banner, they followed the lead of a crazy hag and started to cross the Tenman Bridge.

Just then, clouds gathered over the foothills at Akishino and their tattered clothing absorbed the rains sent down by the Ikoma thunder god.98 The conditions were so adverse that Seedless gathered his army to one side. As he approached to stand under the bridge, he saw a woman of about twenty years of age, her toes unabashed at treading on moss;99 she was crying, despondent. Mystified, Seedless asked her what was the matter. She replied: “I am ashamed to say, but I am the one who is married to the crippled lord, having once pulled our midnight pillows together. I am called Lady Wheel of Kawashima.100 But how sad to be a single wheel,101 for Lord Cripple, pained by this bitter floating world, has just thrown himself into the river. I am so sad that I can’t stand a moment’s separation.102 To seek shelter from a passing shower or to cast oneself into the flow of a river, all is due to the karma of a previous life. Please pray for our departed souls. . . .”

Right after telling her story, she, too, plunged to her death. Seedless, taken aback, tried to pull her out, but she had drifted into the swirling rapids, and not even a trace of her mat remained to be seen. He realized that the couple had lived their last days beneath the bridge. Written on one of the pillars in clumsy strokes of a worn brush was a single poem. Seedless recited it to see how it sounded:

A crawler I am because I am unable to use my shins and loins103

Were I able, how would I live such a sad life afloat.

Overcome with emotion, Seedless could not hold back his tears. Just then, the sky completely cleared, and the sun shone brilliantly. “A trivial matter has distracted me on the way to battle,” he thought. He emerged from under the bridge, and, leading his army, he ascended the path to Takahara.104

There, the three chiefs who had escaped death in previous battles had reassembled a great army. They decorated their sedge hats with hoe-shaped crests and, wearing tangerine baskets for back protection,105 they ordered their men to stand their straw bag shields together in a group and set up camp. The chiefs met in conference with Seedless: “Our men have not won a single battle and have been routed by those paupers. Just as we beggars thought we had completely lost divine protection, we have raised a great army and are here to meet you again. Our alliance has not ended.”106 Seedless, too, told of the hardships of the Battle of Tenman.

“Well now, fellow soldiers, what should we do,” they asked. But opinions were divided. Then, Matsuri Tarō the Heir came forward and spoke: “As often happens in war, losing is a matter of fate. However, I think our allies were routed in these three battles because we underestimated the paupers and were poorly equipped. Kōzu is the finest castle in Japan, and the paupers’ general, Bareman Saburō Dirtskin, is incomparably strong. His strategy is equal to Huang Shih-kung’s skill in tying up a tiger and Chang Tzu-fang’s art in crushing a demon.107 He is not afraid at seeing a large enemy force, and we don’t know what scheme he has concocted. We are unlikely to take the castle with sheer brute force alone. I conclude that we must surround the castle on all four sides and starve them to death.”

After he had spoken, the chiefs all exclaimed: “You are quite right, sir!” And so it came about that, for days and nights, they lay siege to the east, west, south, and north. However, because their provisions of bran, tea dregs, field horsetails, and nameless greens did not run out, the castle showed no signs of falling.

The attackers became bored of the extended siege. As time passed, they began to loosen their sashes and mats, some started napping with puppies in their arms. Some men preferred playing games with fish heads.108 Others asked for tissue paper and braided thongs or trimmed the beards off their straw sandals.109 And others pillaged sacred food, or, drunk on home brew, quarreled among themselves. Under the eaves, another group made a ruckus by raising their voices together and singing, “Da dum, this is the age of the wayfarer’s road.” In such diverse ways they passed days and months, until in the tenth month when the god of poverty, too, goes off to Izumo,110 it became the first year of the era of Heavenly Harmony.111

Startled by a Stick, Dōgan Composes a Great Poem: He Is Scared Out of His Wits by a Dragon Head112

Around that time, a priest by the name of Dōgan was undergoing ascetic training. Wearing a single tattered robe, his prayer gong around his neck, he lived simply with a peaceful heart. “The world passes while I beat my begging bowl,” he said, contemplating the impermanence of it all and using people’s eaves freely, as his hermitage. This indeed exemplified the saying that a great hermit hid in the midst of the city, a realization that was a blessing.113

Once, saddened by the emptiness of his being, especially the void in his stomach, Dōgan went on a pilgrimage to pay his respects to Atago in the Upper District.114 On the seventeenth day, while he was on his way, the eastern and western skies suddenly darkened; black clouds gathered, and a shower overtook him. After waiting for the rain to clear, he continued his journey. With no moon to replace the evening sun, it grew gradually darker, and he lost sight of the path in front of him.

Dōgan thought to himself, “I go off a traveler and return a traveler, with no fixed plan for where to spend the night. I have, of course, no hut tied together with grasses. Tonight I will await the dawn here,” and he stood under the eaves of a stranger’s home. There, a dog barked fiercely, as if accusing him, and almost jumped at him. Nevertheless, Dōgan lay down to sleep and dream without a bedspread. However, the master of the house, awakened by his dog’s incessant barking, came outside carrying a cane. He found Dōgan and drove him away. As Dōgan left, having no other choice, he composed this moving poem:

The dog barking at me all night long was not so bad

Frightened I was, though, by the master’s cane.115

And so he had to walk on. Searching for lodging, he was driven out of one place after another. He wandered about looking for a place to sleep, until he saw a faint, distant light. It was a crudely stained hut with no decorative eave facing.116 While it was not the ancient barrier house of Fuwa,117 there were gaps between wooden shingles of the wind-waiting roof that liked the moon and hated the rain, and the rocks used as weights were about to fall off.118 The overgrown ferns under the eaves, too, suggested that this house, a small rental hut, may have been for sale. So he stopped, thinking, “I will wait for dawn here.”

But, wondering, “Am I going to be driven away?”—he peeked through a break in the thin wall to peer inside. At that moment, his mind and spirit disappeared, and he felt as if he were no longer living. After a while, when he calmed his heart and looked carefully, the thing that had so scared him was none other than a man wearing a dragon’s head. To the man’s left was a Daitoku dancer, and to his right was a man with a full head of hair, wearing a tattered and creased paper dress and holding a fan erect,119 apparently ready to chant, about to start into a sashi.120 In addition, he saw all kinds of people found at festivals, lined up. And at the very end of the line was a tea whisk stem with its whisk missing and a chipped Tenmoku tea bowl.121

Then the man with the dragon’s head spoke, “Every day I disturb the ears of the sick and threaten napping children, and beating the taiko drum for several years now, I have thought little of this world; yet this famine is unbearable. With no energy left in my arm, I can’t raise the drum sticks.” As he thus lamented, the Daikoku dancer said, “Lord Dragon Head, you don’t distinguish between spring, summer, autumn, and winter, so it cannot be that bad. For myself, among the Seven Gods of Fortune,122 I have a rice bag under my foot,123 and I am much loved by everyone. But because people do not need me after the New Year passes, I find it even more unbearable.”

Then the man in paper dress spoke, “I am a scion of the Kanze troupe and travel the great roads making music resound.124 But in recent years there have been so many of my kind that people are completely bored. However, now the era name has changed to Heavenly Harmony, which augurs peace and pleasure. The significance of this is that the characters for ‘Heavenly Harmony’ can be read as ‘two people in harmony.’125 When, in the heavens above, the virtues of the ruler and the ruled are lofty, and when the two—heaven and earth—are in harmony, the branches will not break in the wind that blows every five days and in the rain that falls every ten days.126 Ten thousand things will ripen, and the five grains will never be exhausted. On earth below, the differences between paupers and beggars will end.”

The moment he finished speaking, suddenly, although the wind did not blow, the wooden pestle rattled, the miso strainer moved, and the flames of the Three Heats under the pot flared.127 Everyone vanished in a flicker, and the night turned to dawn’s whiteness. Dōgan went out from under the eaves.

A Deaf Monk Dies and Revives:128 Paupers and Beggars Enjoy Prosperity

Another miraculous event occurred around the same time. There lived a deaf monk called Gufutoku, who was less than honorable.129 His body mixed in the dust of the Five Filths and his heart defiled by the mists of the Three Poisons,130 he noisily invoked the Amida Buddha’s name with determination not to retreat from what he had already achieved. Beating his gong, he shook the wide sky and put the thunder to shame. He was a bane to late morning risers.

This monk suddenly died and found himself at the palace of Enma, the King of Hell. The top official had a demon take him to see the realm of the hungry ghosts131 where there was a plaque on which was inscribed “The Hall of Epidemics.” When the deaf monk asked what this place was, the demon answered: “This is the place where paupers who drop dead on the streets are gathered. Although their spirits come to hell, their souls remain in the shabby world in order to cause an epidemic in the following year.132 Large numbers of people who are not benevolent will die from these diseases. Hurry back to the shabby world and tell people they must perform good deeds.”

The instant Gufutoku heard this, he revived and spread the word in the ten directions. As a result, in district after district, alley after alley, indeed everywhere, spectacularly, people cooked rice gruel. Flowing from ladles, the white rice gruel was like the waterfalls of Nachi and Mino’o.133 The large roads overflowed with rice gruel and sparkled, like moonlight shining on waves. It was difficult to count those gathered who had been deprived of the three necessities of life.

Meanwhile, the Battle of Kōzu dispersed, and there was harmony between the paupers and the beggars. This was due exclusively to the virtue of the Era of Heavenly Harmony. The five grains grew abundantly, and rice with grains 1 sun and 8 bu long started to grow at this time.134 Daikon radishes grew so large that people carried on their backs a fat daikon with a round white radish stuck in it,135 and, in the midst of winter, a spring of young plants appeared. To their glory, the paupers had their ladles lacquered, and the beggars’ iron-hooked poles were now made of gold with their names inscribed. They wore forbidden brocade, never picked up any paper other than the best tissue paper,136 and, wherever they threw away leftovers, people were troubled. The on-duty beggars, curtains drawn round them, played go and shōgi, instead of working. Single Chopstick of Tennōji passed his days seeking fine food. Bamboo Fence of Dōtonbori, in a cool summer cottage, fanned himself with a lacquered fan, puffing on the smoke of impermanence that blew elsewhere. Homeless of Tobita sang manzairaku,137 while the waves of the He and She Ponds added to the sound of the hand drum. Thus the world became one of both paupers and beggars united.

Two texts are available: the version anthologized in Kokkei bungaku zenshū (Complete Collection of Early Modern Comic Literature), vol. 8, ed. Furuya Chishin (Tokyo: Bungei Shoin, 1918) and the Hinin Taiheiki: eiri (The Illustrated Paupers’ Chronicle of Peace), Tokutomi Sohō, ed. (Tokyo: Minyūsha, 1931).

Notes

Tosa Shōgen might refer to the painter Tosa Motonobu (1424?-1525?), who was granted the court rank of shōgen (colonel of the Inner Palace Guards, Right) in 1495. However, other members of the Tosa painter family, including Yukihiro (ca. 1406-34), Mitsumoto (ca. 1530-68), Mitsuoki (1617-91), and Mitsuoki’s son Mitsunari (1646-1710), were granted the same court rank. He-gassen scrolls depicting farting battles and contests were painted in the Edo period.

Kan is a unit of money equaling 1,000 mon. Mon is a currency that began circulating in 1336 and was replaced by the yen in 1870.

The phrase, “umaretsukige no maruhadaka hakkan,” encompasses several terms: umaretsuki no maruhadaka (born stark naked), tsukige (dapple-grey horse, a fine mount for military leaders), hadauma (Bareman Saburō Dirtskin’s horse), and hadaka hyakkan (a man penniless but worth one hundred kan).

In the twelfth century B.C., the brothers Po I and Shu Ch’i (Japanese pronunciation Hakui and Shukusei) unsuccessfully tried to dissuade King Wu of Chou from killing King Chou of In. The brothers hid in the mountains and eventually starved to death.

According to Buddhist beliefs, the Three Great Calamities (fire, water, and wind) occur after the first two of the four stages of the world (becoming, staying, destruction, and vacuity), ushering in the third stage. The interval between the three disasters and the stage of vacuity is said to have twenty cycles.

An allusion to a line in the poem “Recommending Wine” by T’ang Dynasty poet Po Chü-i: “Even if wealth reaches the Big Dipper after life, it is inferior to one barrel of wine in this life.” See, for example, Burton Watson, Po Chü-i: Selected Poems (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 127-31: “Before the big dipper traverse migrating wide geese under the moon over the south tower the sound of fulling cloth for the winter” comes from a poem by Liu Yüan-shu in the Wakan rōeishū (Japanese and Chinese Poems to Sing, compiled around 1013). See, for example, Thomas Rimer and Jonathan Chaves, Japanese and Chinese Poems to Sing (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 346.

Amida Buddha is said to have meditated on his (her) pledge to save humans for the period of five kalpas. A kalpa is the time it takes for the highest mountain to be worn down by a feather being brushed over it once every hundred years.

From the famous opening lines of the Tale of Heike: “The Gion bell tolls the impermanence of all things. / The color of the twin sala trees’ blossoms / Attests to the fact that even the prosperous are bound to decline.” Helen McCullough, Genji & Heike: Selections from The Tale of Genji and The Tale of the Heike (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), 265.

A bridge over the Higashi Yokobori River; also the name of the area west of this river. Common places for begging were by the entrances of bridges, in front of temples, and on streets, especially in the pleasure quarters.

All are Osaka districts. Tobita, in western Osaka, was known for its graveyard and execution site. Tobita, therefore, suggested one sentenced to death. Dōtonbori, the area south of the Dōtonbori River, was designated in 1626 as a theater district, and its entertainments drew crowds. Tennōji is the sites of the four Tennō temples. Tenma was known for the Tenmangū Shrine, which enshrines Heian poet and scholar Sugawara no Michizane (845-903). A tax-exempt kaito was found in each of these four places.

“On-duty beggars” (bankojiki) refers to beggar guards (kaitoban) who stayed in a shed just outside an urban residence to protect against theft and other disturbances.

Common expression for being forlorn. The expression is used in Book 9 of the Taiheiki when the Hōjō warriors in Kyoto find that Shogun Ashikaga Takauji has betrayed them.

Sangō, literally “three rivers.” Phrase that originally referred to the three longest rivers in China here applied to Osaka.

“Becoming a pauper” refers to famine refugee beggars, differentiating them from permanent city beggars.

The standard hairstyle for men was a topknot and a shaven front. The poor and discriminated are said to have worn a bun without shaving the front (like women) or to have kept their hair cut and unbound (like children).

The Japanese version of Chung K’uei, a Chinese god said to expel demons and diseases, is usually represented as big-eyed, angry, bearded, booted, and dressed in black, holding a drawn sword. The image is derived from a legend about T’ang Emperor Hsüan-tsang’s dream in which Chung K’uei, a local official, appeared and conquered evil spirits to cure the emperor’s illness.

An iron gaff is either a long-handled weapon used to pull an enemy boat or a short-handled tool for catching fish. Fan K’uai and Chang Liang (Hankai and Chōryō in Japanese) are heroic retainers of the Han dynasty founder Liu Pang. The lengthy account in the Taiheiki, Book 28 of the battles of Han and Ch’u emphasizes Fan K’uai’s righteous rage in the well-known Hungmen banquet scene (206 B.C.) and Chang Liang’s military strategies at Hungmen and elsewhere. Collecting waste paper and waste cloth to recycle was one of the ways that hinin earned a living. See Ōsakashi-shi hensanjo, Shinshū Ōsakashi-shi shi, vol. 3 (Ōsaka: Ōsakashi, 2009), 865.

Yunoko is rice gruel made from the burnt rice that sticks to the pot. Bareman Saburō Dirtskin’s speech humorously echoes the tone of military leaders.

Kōnoike, literally “storks’ pond,” is a place in Settsu province, now around Kōike, Hyōgo Prefecture, known as a producer of sake. A sake bag is used to squeeze out unrefined sake.

Rice, barley, two kinds of millet, and beans were the five standard grains. “Scooping steamed wine rice” (sakameshi suku’u, also called sakakowai) is a reference to activities of the winter brewing season. It also suggests that there will be enough rice to brew in the next big harvest. Processing grains was usually banned during famine.

Roof-tile making was a major construction industry in Osaka. A record remains of a master tile producer who shipped 2,861,000 roof tiles to Edo in the fourth month of 1704. See Ōsakashi-shi hensanjo, 818.

Thorny barriers (sakamogi), uprooted trees placed upside down as blockades, are frequently mentioned in the Taiheiki.

This passage echoes a famous scene in Book 9 of the Taiheiki. On turning openly against the Hōjō, Ashikaga Takauji asks Hikida no Myōgen to write a supplication at a Hachiman Shrine in Shinomura.

Jinmu (reign ca 660 BC-585 BC) is the legendary first emperor of Japan. Nintoku, exact reign dates unknown but believed to be 313-399, was the sixteenth Japanese emperor. Go-Daigo (885-930), reigning during the Engi era in the Heian period, has been regarded as an ideal emperor because of his successful imperial rule without regency. The first imperial poetic anthology Kokin wakashū (Collection of Poems from Ancient and Modern Times, commonly abbreviated as Kokinshū) was compiled in 905 during his reign. Murakami (926-967) of the Tenryaku era (947-957) also ruled directly. “Return to the old days of Tengi and Tenryaku” was the slogan of Go-Daigo, the central imperial figure in the Taiheiki.

The barbarians to the east, west, north, and south of China. Here, the beggars in the four regions of Osaka.

In the Taiheiki, Ashikaga Takauji offers supplication in the sacred hall along with a whistling arrow. His immediate subordinates follow his example and offer one whistling arrow each.

In the Taiheiki, the sign that the supplication Ashikaga Takauji asked Myōgen to write to show success is a pair of turtledoves that flutter over the white banner. They then perch on the bead tree before the Department of Shintō in the old palace.

Nintoku ruled at the Kōzu Palace in Naniwa (old name for the Osaka area). The characters for Kōzu can be read “Takatsu” here to better match the first phrase (takaki ya ni) of the original poem quoted in the following passage.

This poem ascribed to Nintoku is found in the Shin kokin wakashū (New Collection of Poems from Ancient and Modern Times, commonly abbreviated as Shin kokinshū) the anthology, commissioned to continue the Kokinshū and presented to the emperor in 1205 at the three-hundredth anniversary of the Kokinshū. However, the style of the poem suggests a much later date than Nintoku’s reign. Seeing his subjects suffering from poverty, Nintoku is said to have suspended taxes for three years. The poem was thought to express his happiness when his subjects’ began to recover from poverty. The use of honorifics in the passage preceding the poem (eiryo ni kaketatematsuru, or “presented to the Emperor for his imperial consideration”), suggests that the author of the Hinin Taiheiki considers the poem to have been written by a vassal.

Cloth cheek covers were worn by peasants, street entertainers, and thieves; they replace warrior helmets here. Bowing nine times was a ritual gesture of the highest respect used for the emperor or a high-ranking priest.

Ikutama (also Ikudama) is the name of a shrine in Ikutama in the Tennōji area of Osaka. Valiant warriors of the past trembled with excitement; paupers shook their bodies from nervous habit.

A parody of a typical description of brilliantly attired warriors in warrior tales. The armor is dōmaru, designed for foot soldiers and characterized by a continuous sheath-like cuirass that is wrapped around the body of the wearer and fastened at the right side. It was particularly popular in the Muromachi period. “With long hems” (kusazurinaga ni) means wearing armor with longer kusazui (corded hip and thigh guard hung from the torso) of seven or six, instead of five, tiers. The expression is especially associated with ōyoroi, loosely-fitting armor for mounted archers of earlier times.

Kizu in the Kyoto area is a port town on the Kizu River. Imamiya is named after the Imamiya Shrine originally established in the Heian period as a place to pray for safety from an epidemic that spread through the Kyoto area in 993. Abeno, an area in southern Osaka, is said to be the site of the death of court noble Kitabatake Akiie (1318-1338), a hero in the Taiheiki.

Enami is an old name for an area in Osaka. Kyōbashi is a bridge across the Neya River in Osaka; it is also a bridge in Fushimi in Kyoto over a tributary of the Uji River. Amijima (literally, “fish net island,” because fishermen used to dry their nets there) is a town where the Yodo and Neya Rivers join. Later it became famous for dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s Bunraku puppet play Love Suicides at Amijima (Shinjūten no Amijima, first performed in 1721).

Kitano Tenmangū Shrine is in the Kitano area of Kyoto. Dōshima in Osaka was an entertainment district in the Edo period. Fukushima, also in Osaka, is on the lower reaches of the Yodo River.

Chōja (an elder) here means the female owner of a pleasure house, as an extension of its more conventional meaning of the mistress of an inn along an official travel route.

Yoshiwara is the name of two places in Osaka: one a cemetery in the northern part of the city near Tenman, and the other a neighborhood in southeastern Osaka. However, the name is certainly used here to recall the most famous Yoshiwara, the pleasure quarter of the city of Edo, which was established in 1615 (Moto Yoshiwara) and moved to Asakusa in 1656 (Shin Yoshiwara) after a fire.

Ikasuri (also pronounced Zama) is a shrine in Higashi-ku, Osaka. The Tenmangū Shrine Festival, traditionally held on the twenty-fifth day of the sixth month, now on July 25, is one of the biggest festivals in Japan.

One ri is a distance of nearly four kilometers. The phrase that references the long lifespans of the crane and tortoise signifies a felicitous world.

A familiar Chinese saying quoted in the Taiheiki in the lengthy note on the war between Wu and Yüeh (Book 4) and in Ashikaga Takauji’s letter to Go-Daigo accusing Nitta Yoshisada (Book 14).

Five begging bowls is a play on the helmet with a five-tiered neck protector (gomai kabuto or gomai shikoro) that extended from the head protector (hachi). Great armor (ōyoroi) is medieval armor worn in mounted battles with its skirt divided into four flaps; around the Muromachi period, simpler forms of armor, dōmaru or haramaki, better suited for fighting on foot, grew more popular. Detailed descriptions of helmets and armor such as this are important ingredients in tales of battle scenes.

“Unlacquered chopsticks used for dyed teeth” (hazome no zōbashi) puns on battle arrows with dyed arrow-feather” (hazome no soya).

Iwakuni, on the eastern end of today’s Yamaguchi Prefecture, was a famous producer of paper made of kōzo (a kind of mulberry). Thick paper made by gluing several layers of Iwakuni paper was used for book covers.

They raise the beggars’ cry instead of the warriors’ war cry. (A pun on “war cry” and “cry for a meal.”)

Sun Ch’en (Japanese Son Shin), an ancient Chinese sage, wove mats for a living but excelled at poetry and calligraphy. All he had for bedding, even in winter, was a pile of straw, which he spread in the evening and put away in the morning.

Bareman Saburō Dirtskin’s strategies echo those that Kusunoki Masashige employed in battles at Akasaka and Chihaya described in the Taiheiki, Books 3 and 7.

Thorny barricades (sakamogi), made of uprooted trees and bushes, is a standard barricade mentioned in the Taiheiki and other tales of war.

In the Taiheiki, the Kusunoki troops threw boiling water (the Battle of Akasaka), torches (the Battle of Chihaya), and big rocks and lumber (both battles). The torches were thrown at ladders that the Bakufu’s eastern troops used to climb the walls of the Chihaya castle after drenching them with oil.

The leather-soled sandals recall leather-reinforced shields in the Taiheiki, Book 3. At the Battle of Akasaka, Kusunoki Masashige prepared a hanging wall outside the regular wall of the castle. When Eastern warriors began climbing the outside wall, Kusunoki warriors let it fall and then threw big rocks and lumber. The enemy warriors tumbled down the slope; hundreds died. Their leaders concluded that this was because the warriors, eager to attack, were not prepared properly with shields and weapons. So each warrior carried a sheaf reinforced with hard leather.

The paupers prepared slippery squash pulp just as the Kusunoki troops in the Taiheiki prepared long-handled ladles full of boiling water to shock the Eastern warriors.

Sushi originally meant pickled fish. Pressed sushi, an Osaka specialty prepared by closing a lid tightly on salted fish placed over vinegared rice and packed in a box, became popular in the Edo period.

The Heike were routed by Yoshitsune’s 1185 surprise attack at Yashima in a northern area of Takamatsu in Kagawa. The Battle of Kurikara Valley in Tonami, Toyama was led by Yoshinaka in 1183.

Saimei. Here chōri refers to the liaison between temple and government. After the battle, Saimei was arrested and beheaded.

Shōman, or Shōman’in, is a separate monastery of Tennōji Temple, where many actors and women working in the pleasure quarters worshipped. Kōshindō is a hall that enshrines the god of Kōshin; here probably the one in Tennōji district of Osaka.

Ryū Hakurin in Japanese. Yüan dynasty warrior who brought down the previous ruler and became commander-in-chief of the military.

Yao, a legendary Chinese emperor, invited Hsü Yu, a pure-hearted man, to be his successor. Saying that he had heard an unclean thing, Hsü Yu washed his ears in a river and hid in the mountains.

This description of the beggar warrior Sekizoronosuke contains references to sekizoro, Edo-period street performers who, in twos and threes, went around in the twelfth month begging for rice and money. They wore hats decorated with ferns and red or white clothes around their faces, with only their eyes showing. They chanted, “Sekizoro gozareya, hah! sekizoro medetai” (This is the season, come forward and give, this is the season, blessings). “A helmet of ferns hanging long over the shoulders” parodies the ample neck plates of a helmet. sekizoro performers wore urajiro or yamagusa ferns commonly used for New Year decorations on their heads. Yuzuriha, “give-away leaves,” is the name of a tree so called because old leaves give way to new leaves in a conspicuous manner. While sekizoro performers wore white cheek covers, others wore red. See Kyōto Burakushi Kenkyūjo, ed., Chusei no minshū to geinō (People and Entertainment in the Medieval Period) (Kyoto: Aunsha, 1989), 116-17.

“Fukufuku taitai (or, in another reading, daidai), sah sah gozareya gozare,” a variant of the sekizoro chant.

“Red hair” here is shaguma, which is yak or white bear tail dyed red for ornamental or other purposes, or hair that resembles it.

The name Tobisonuke carries the image of a kite, the bird that snatches things and flies away, as in the saying, “to have fried tofu snatched by a kite.” Another association is tobi no mono (fireman). Edo firemen worked with tobiguchi, a hook with a long handle that resembled a kite’s beak.

The licensed beggars wore tablets to identify themselves to the authorities. Here a play on kasajirushi, or cloth badges in the shape of miniature flags, worn by warriors over their helmets to identify their side in battle. These badges often appear as crucial plot mechanisms in such classic warrior tales as the Taiheiki.

The name Toki suggests the charity food served at temples rather than the regular morning meal for priests.

The following is a traditional michiyuki (travel) scene in which puns are made using the names of various places.

A beggar either lives in a small hut or carries rush matting for shelter. These four lines make use of the vocabulary of pining (longing), houses, roof-tile making, and the Buddhist parable of the burning house in order to lead up to the place name “Pine House District.”

Buddhas and bodhisattvas compassionately soften their light (i.e. to conceal their glory) and mingle among living things on Earth in order to bring spiritual salvation.

Like Hades in Greek mythology, Enma is both the judge of the dead and the guardian king of the netherworld.

Red hair (akagashira) is dry, brownish hair, from exposure to the sun, unkempt and not treated with hair oil. Akagashira (red hair) and akagari (calluses) resonate.

Karakushi (Chinese or Korean comb) is an imported ornamental ivory comb or an imitation thereof. Play on the phrases for “being barred at a barrier house” and “lice being combed out of the hair.”

The white road between two rivers (niga byakudō) means the narrow path to enlightenment between the rivers of water and fire, or between greed and anger.

These bandits are nobushi, literally “field-lying warriors.” Yamada, Saidera, Suita, Katayama, Harada, Tarumi, and Sanbōji are neighborhoods in the area of Suita to the north of Osaka, north of the Kanzaki River and south of the great western road. At that time, this area was rural and distant from the city.

Late sixteenth-century water forces used hōroku, round bullets made of sulfur, coal, rosin, and other materials. Pun on hōraku, a flat earthen pan used for roasting peas, rice, and salt.

These areas also are to the north of the city within the large bend of the Yodo River and north of Tenman.

Yakuharai, an exorcist for outcastes, who, on New Year’s Eve and other occasions, went through the streets offering prayers of good fortune and charms against calamities.

Echoes a poem by Saigyō: “Akishino ya toyama no sato ya shigururan Idoma no take ni kumo no kakareru” (A late autumn shower must be falling over the mountain villages in Akishino, for clouds hang over the peak of Mount Ikoma). Shin kokin wakashū, poem 585. Akishino is a place in Nara. See Tanaka Yutaka and Akase Shingo, eds., Shin kokin wakashū (Tokyo: Iwanami, 1992).

Pun on kata-waguruma (single wheel), Kuruma Gozen (Lady Wheel), and katawa (single wheel, meaning physically disabled).

Izari (sidling, or a “cripple”) is an expression that is also used when a boat advances slowly in the shallows, its bottom grazing the riverbed. Thus it ironically echoes the word uki (floating) in uki sumai (bitter abode).

Ōe no saka, or correctly Oinosaka (“the slope of old age”), is a pass to the north of Ōeyama mountain in Kyoto.

Chōri nakama, translated here as “chiefs and fellows.” The organized hinin inōsaka were called nakama, or, in full, shikasho nakama, or kaito nakama. Shikasho denotes the people of the four kaito, i.e. the beggars.

Kōsekikō and Chō Shibō in Japanese. Huang Shih-kung was a recluse during the Ch’in Dynasty. Chang Tzu Fang, better known as Chang Liang (in Japanese: Chō Ryō), was one of the three heroes who helped found the Han dynasty.

In a well-known passage in Book 7 of the Taiheiki, the Hōjō troops, tired of the long siege of the Chihaya Castle, whiled away their time by engaging in such refined activities as writing linked verses, playing games of go, tea tasting, and poetry competitions.

Collecting waste rice paper and scrap cloth was one way for Osaka hinin to make a living. They dried and recycled what they picked up.

There was a belief that all the native gods assembled at Izumo in western Japan in the tenth month of the year. The literary name for this month is Kannazuki, or, “the godless month.”

The episode of Dōgan (“Buddhist Vow”) is reminiscent of an episode in Taiheiki, Chapter 35, titled “The Tale of the Kitano Vigil.” In this episode, the priest Raii spends a night at Kitano Shrine and overhears the conversation among three men: a recluse around age sixty, who had been a former warrior, speaking with a Kantō accent; a pale, retired court scholar; and a lean and learned monk. The recluse laments the corruption in the warrior world. The courtier points out that the aristocracy is also corrupt because there are no sincere vassals who reprimand the emperor. The monk comments that neither warriors nor courtiers are to blame for the disorder under heaven but that it is instead a matter of cause and effect. The three laugh aloud and leave since it is already dawn. Raii, too, leaves.

“A small hermit hides in mountain groves; a great hermit in the imperial court and market places” (attributed to fourth-century poet Wang K’ang-chü. See Watson, The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 175.

Atago Gongen Shrine atop Mount Atago of Kyoto. Visiting the shrine on the twenty-fourth day of the sixth month was believed to be as effective as one thousand visits on ordinary days.

Cf. Poem 415, “Yomosugara tataku kuina wa ama no to wo akete nochi koso oto sezarikere” (Water rail that called all night long makes no sound now that heaven’s door is open), attributed to Minamoto no Yoriie in the sixth imperial poetic anthology, The Collection of Verbal Flowers (Shika wakashū, ca. 1050).

Fuwa barrier house is remembered especially in Fujiwara no Yoshitsune’s poem: “Hito sumanu Fuwa no sekiya no itabisashi arenishi nochi wa tada aki no kaze” (Wooden eaves of an uninhabited barrier guard’s house, after it has gone to decay, the only thing here is the autumn wind), Shin kokin wakashū, poem 1599 (Quoted in, for example, Theodore de Bary, Eastern Canons (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 333.

The roof is makeshift, made of boards about one foot by eight inches wide held in place with rocks and other weights.

Three types of entertainers: a dragon mask drummer (who visited houses in Osaka, Edo, and other places from the second day of the first month till the beginning of the second month), a Daitoku (god of wealth and happiness) dancer, and a Noh performer. The Noh performer’s full hair, as opposed to a topknot and a shaven forehead, is a reference to the hairstyle of the discriminated class. Sashi is a chanted passage in a Noh play. A lead or a support character’s sashi often occurs at the beginning of the play.

A bamboo whisk is used to stir powdered tea. Tenmoku refers to porcelain tea bowls made in the T’ien-mu mountain area of China; tea bowls in general.

The Seven Gods of Fortune are Daikoku, Ebisu, Bishamonten, Benzaiten, Fukurokuju, Jurōjin, and Hotei.

Daikoku wears a hunting robe and a cloth hat, carries a big bag and a wooden treasure hammer, and stands or sits on bags of rice.

Kanze is one of the main schools of the Noh theater, derived from the Yūzaki Troupe founded by Kan’ami (1333-84).

The Chinese character for heaven can be broken down into radicals meaning “two” and “person,” evoking the phrase “two people in harmony.”

An idiom, from a Chinese saying, for peace throughout the land: “In peaceful times, the wind blows once every five days causing a branch to break, and the rain falls every ten days without causing a lump of earth to slide.”

Buddhism stipulates three kinds of torment (or the Three Heats) for snakes and dragons: to be burned with hot winds and hot sands, to be deprived of dwellings in evil winds, and to be devoured by a monstrous bird.

This echoes an episode in the recluse’s story in “The Vigil at Kitano” in the Taiheiki. A holy priest, following his sudden death, visits hell for thirteen days and sees Go-Daigo suffering torture because of five sins he committed when alive. Chapter 20 of the Taiheiki introduces a traveling monk who visits hell. At dusk he does not know where to stay. A mountain ascetic appears and offers to take him to a lodging. There, the priest witnesses the hellish torture of Yūki Munehiro Dōchū. The mountain monk tells the priest that Yūki’s wife and children should copy sutras to rescue Yūki. The gong of a village temple is borne on the wind through the pines, and everything disappears. Only the priest remains sitting, lost, on the dewy grass in a field.

Gufutoku-ku, the torture of seeking without attaining, is one of the eight tortures in Buddhism.

According to Buddhism, phenomena at the end of the world. The Five Filths are (1) natural disasters and pestilences; (2) human beings having evil thoughts; (3) human beings living short lives; (4) raging frustrations; and (5) lowering of standards that drive human beings to evil deeds. The Three Poisons are the three basic evils that human beings must conquer: greed, anger, and ignorance.

The demon official is Kushōjin, twin gods based on Indian myths. Starting from the day a person is born, they are perched on his shoulders; one records his good deeds and the other his bad deeds. After the person dies, these records are used in inspection at the office of Enma. In other accounts, Kushōjin is simply an inquisitor and recorder seated by Enma. In the cosmology of medieval Japanese Buddhism, hungry ghosts (gaki) are beings condemned to an existence of insatiable hunger. With distended bellies and needle-thin throats, they wander the earth unseen by most people.

Shabby world (shaba in Japanese, sahā in Sanskrit): this Buddhist term in common parlance has come to mean “the human world where sufferings abound.”

1 sun 8 bu is about 5.5 centimeters. The appearance of rice with such grains is reported in the Procedures of the Engi Era (Engishiki)—a compilation of rules and regulations completed in 927—where it is said that, as a result of the spiritual (auspicious) dreams of Emperor Sujin, the deity of seeds, rice with grains 1 sun 8 bu long was harvested.

The word kabura (round radish) also means whistling arrows. Traditionally, a warrior carried regular arrows on his back in a quiver with two extra arrows on top. These were whistling arrows for signaling the beginning of a battle or scaring off evil spirits.

Embroidered brocade (tsuzure, short for tsuzurenishiki), which commoners were forbidden to wear, was a sarcastic name for beggars’ tattered clothing; tsuzure also means a patch-cloth garment or tattered cloth. The high-quality tissue is Nobe (short for Nobegami), tissue paper slightly smaller than 11 by 8.5 inches produced in Yoshino in Yamato, used especially in the pleasure quarters.