|

Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Volume XXVII, Special Issue in Honor of Kyoko Selden (2015); also available here |

This issue of The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus is the first of three special online issues that can be read in conjunction with a 2015 special issue of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society (Volume XXVII).1 Together the issues offer examples of Kyoko Selden’s literary translations and writings that span Japanese history, literature, and multiple genres. The two journals were venues through which Kyoko shared much of her work. These poems, stories, novellas, essays, plays, memoirs, and biographies—drawn from her more than twenty books and fifty short pieces—exemplify her belief in the humanizing power of literature and art, concern for the human toll of historical events, and gentle humor. They reveal new dimensions of established authors while ensuring that marginalized voices are heard. The selections highlight Kyoko’s emphasis on women writers and her interlocking themes: war and peace, classical literature and art, Ainu traditions, Okinawan literature, atomic cataclysm, music, education, and childhood, among others. We have prioritized texts that have not been published and those that were first circulated in private venues; included are a few of her many contributions to the Asia Pacific Journal and Japan Focus. We have completed translations that Kyoko did not have a chance to finish before her passing in January 2013.2

|

Flute Boy, Watercolor by Kyoko Selden |

Kyoko Selden—educator, translator, editor, calligrapher, painter, and poet, among other talents—was born in Tokyo in 1936; her father Irie Keishirō was a journalist and later professor of international law. As detailed in her memoir, Kyoko experienced war as a child, first at her family’s home in Tokyo and then in the Nagano countryside with her brother Akira and other schoolmates who were relocated to safety from bombings shortly before the firebombing of Tokyo. She attended secondary school in Tokyo and graduated with a degree in English from the University of Tokyo in 1959. With the help of a Fulbright Fellowship, she studied English literature at Yale University, becoming one of the first Japanese people to travel abroad before passports became more easily available in the 1960s. Kyoko earned a doctorate in English literature in 1965 and in subsequent decades demonstrated her ability to translate into both Japanese and English. At Yale, she met Mark Selden, whom she married in 1963; for fifty years, Kyoko and Mark partnered in projects combining social activism, literature, art, and translation. At Yale, she also became friends with Noriko Mizuta, with whom she prepared three anthologies of Japanese women writers (More Stories by Japanese Women Writers: An Anthology [M.E. Sharpe 2011], The Funeral of a Giraffe: Seven Stories of Tomioka Taeko [M.E. Sharpe 1999], and Japanese Women Writers: Twentieth Century Short Fiction [M.E. Sharpe 1982]). Kyoko taught at Dean Junior College, National Taiwan Normal University, Tsuda College, and Washington University before Cornell University, where she instructed modern and classical Japanese language and literature as a senior lecturer. Kyoko helped foster generations of scholars in Japanese literature, history, and the social sciences through collaborative projects, as evidenced by the many joint translations in this issue, and by designing teaching materials, such as her book series Annotated Literary Gems (Cornell East Asia Series, 2006 and 2007 with additional volumes in progress). It is no exaggeration to say that Kyoko helped shape the American canon of Japanese literature and the field of translation studies. The Kyoko Selden Memorial Translation Prize in Japanese Literature, Thought, and Society was established at Cornell in 2013. As Kyoko’s Cornell colleague Brett de Bary aptly observed in a personal email and elaborates in her preface to the special issue of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society, “Kyoko appears to be one of those people whose outlines emerge so overwhelmingly at the moment of death. How quietly powerful and prolific she was!”

This Asia-Pacific Journal issue opens with Kyoko’s work on classical warrior tales and poetry. In the 1980s, Joan Piggott (Gordon L. MacDonald Chair in History, University of Southern California) and Kyoko began translating and annotating sections of the fourteenth-century Taiheiki: The Chronicle of Great Peace, Chapters Thirteen through Nineteen (out of forty), picking up where Helen Craig McCullough’s seminal The Taiheiki: The Chronicle of Medieval Japan (first published by Tuttle in 1979) left off.3 These initially provided materials for their interdisciplinary Taiheiki course, first taught at Cornell University in 1992 and still offered at the University of Southern California. Excerpts from Chapters Thirteen and Fourteen, published for the first time in the special issue of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society, dramatize events of 1335 and exemplify the gory battles, alluring subplots, cultural allusions, and character sketches that comprise the Taiheiki. They are paired with renga (linked verse) by the basara (flamboyant) warrior Sasaki Dōyo (1295?-1373) selected from the Tsukubashū (Tsukuba Anthology, 1356-57), the first of two official medieval renga collections, and the Hinin Taiheiki, or The Paupers’ Chronicle of Peace (co-translation with Joshua Young). One of many Edo-period (1600-1868) Taiheiki parodies, the Hinin Taiheiki is unique in its inclusion of actual poverty, unrest, and famine. In this mock-heroic tale based on historical events of 1681, Osaka beggars memorably and hilariously attempt to drive famine refugees from the countryside out of the urban areas they deemed their own territories.

The Takarazuka Concise Madame Butterfly (Shukusatsu Chōchō-san) by Tsubouchi Shikō (1887-1986) exemplifies Kyoko’s attention to historical adaptations and the intersection of literature and other media. This charming Japanese version of the 1903 Giacomo Puccini opera Madame Butterfly, told from the perspective of the female protagonist, was performed by the Takarazuka all-female revue in August 1931. It is part of Kyoko’s project with Arthur Groos (Avalon Foundation Professor of the Humanities, Cornell University) on the history of Italian opera in Japan.

A goal of Kyoko and Mark’s work has been to ensure that the trauma of war, particularly the perspective of civilian victims, never be forgotten. This is evident in their edited book The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (M.E. Sharpe, 1989) and numerous articles and literary translations published in the Asia-Pacific Journal. Reprinted here are poems by atomic victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These poets— young and old, amateur and professional—use a range of poetic styles, from haiku and tanka to free verse, to powerfully convey the firsthand experience of nuclear disaster. Also reprinted is Masks of Whatchamacallit: A Nagasaki Tale (Nanjamonja no men, 1976), an evocative story of women’s emotional and physical experience of radiation sickness by Hayashi Kyōko (1930-), the outstanding Nagasaki novelist and chronicler of the bomb and its legacies, and haiku by Mitsuhashi Toshio (1920-2001) about war memory and atomic bombings, among other topics. Mitsuhashi was a member of the Shinkō Haiku (Newly Rising Haiku) movement that the Japanese government in the 1940s deemed a threat to “national polity” (kokutai) and silenced. The themes of these texts are further expounded in Kyoko’s vivid memoir of childhood during war in Tokyo and Nagano, with an afterword written by her brother Akira.

Also represented in this issue is Kyoko’s interest in Ainu oral traditions and contemporary Okinawan stories that creatively use language to provide deeper understanding of these embattled cultures and their past and present on the peripheries of the Japanese empire. Included are two examples of Ainu kamuy yukar, epic songs of gods and demigods, one of three main genres of Ainu literature, in which a human chanter impersonates a deity. “The Song the Owl God Himself Sang ‘Silver Droplets Fall Fall All Around” (Kamuichikap kamui yaieyukar, ‘Shirokanipe ranran pishkan’) was translated from Ainu into Japanese by Chiri Yukie (1903-22) and published in 1923 by Kyōdo Kenkyūsha, a press presided over by the ethnologist Yanagita Kunio. “The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi” (Ainu no min’wa: kaze no kami to Okikurmi) was retold in modern Japanese by Kayano Shigeru (1926-2006) and published as a children’s book with illustrations by Saitō Hiroyuki in 1999. Both kamuy yukar sing of gods who protect and teach humans; they demonstrate how Chiri and Kayano worked to preserve Ainu culture and language and make that literature accessible to Japanese. We present the beginning section of Okinawan author Sakiyama Tami’s (1954-) Swaying, Swinging (Yuratiku yuritiku, 2003), which portrays an imaginary, legend-rich island, all of whose residents are older than eighty. In this novella, comprised of stories within stories, Sakiyama embeds multiple Okinawan languages in her prose to depict the lives of islanders in connection with the spirit of the sea that surrounds them and voices from the past. (A translation of the novella in its entirety appears in Islands of Protest: Japanese Literature from Okinawa, edited by Davinder Bhowmik and Steve Rabson, University of Hawaii Press in 2016.)

Excerpts from three longer works represent Kyoko’s explorations in art history and aesthetics. First, Kyoko translated the extensive catalogue on Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture, 1185-1868, held at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. in 1988 and 1989, the first exhibit anywhere, including Japan, to present the artistic legacy of daimyō (regional lords) from the rise of warrior rulers in the twelfth century to the dissolution of the feudal system in 1868. Second, in his “Ukiyo-e Landscapes and Edo Scenic Places” (Ukiyo-e no sansuiga to Edo meisho, 1914), author Nagai Kafū (1879-1959) offers a wealth of information about ukiyo-e artists, schools, and movements. This lyrical essay, the translation of which first appeared in the December 2012 issue of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society (Volume XIV), epitomizes many of the themes of Kafū’s literature and his faith in the ability of artists to capture the tenor of their times and the power of art to shape the ways people view urban daily life. Third, Cho Kyo (Professor, Meiji University) presents a cultural history of female beauty in China and Japan in his The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty (Bijo towa nanika: Nitchū bijin no bunkashi, 2001). Kyoko’s complete translation of this book, which is excerpted here, was published at Rowman and Littlefield in 2012.

For over thirty years, Kyoko was involved in the Talent Education (Sainō kyōiku) movement, as a parent of three children learning to play violin and cello, and as a translator of major works of the Suzuki Method, which became popular in postwar Japan and then, from the early 1960s, spread throughout the United States, Europe, and other parts of the world. Created by violinist Suzuki Shin’ichi (1898-1998), whose biography Nurtured by Love (Ai ni ikiru, 1966) is excerpted here, the Suzuki Method teaches children classical music while fostering their motor skills, concentration, and character. Nurtured by Love, one of Kyoko’s many co-translations with her daughter Lili Selden, displays her interest in biography as well as music and childhood education.

Among Kyoko’s last translation projects was Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense (Dainana kankai hōkō, 1931) the best-known novel of author Osaki Midori (1896-1974). This fragmented novella, the full translation of which is only available in the Review of Japanese Culture and Society special issue, is replete with inventive use of language, heightened sensory perceptions, parodies of psychology, and cinematic narrative styles. It represents the culmination of Osaki’s modernism and her creation of female protagonists, who like the author, were attempting to make lives for themselves in Tokyo. This story of four youths—a woman, her brothers, and childhood sweetheart who live together, passionately pursue their studies, and are obsessed with romantic love—was Osaki’s final publication before she retired to her home in the remote Tottori countryside. As exemplified by Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense, Osaki’s literature is marked by an anti-realist, anti-worldly imagination, which conjures a fantastic realm beyond the everyday. Osaki displayed a writer’s individuality within a social milieu that restricted the expressive practice of women. The rediscovery of Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense by literary critics in the 1960s led to a reevaluation of Osaki’s work and her influence on female authors.

|

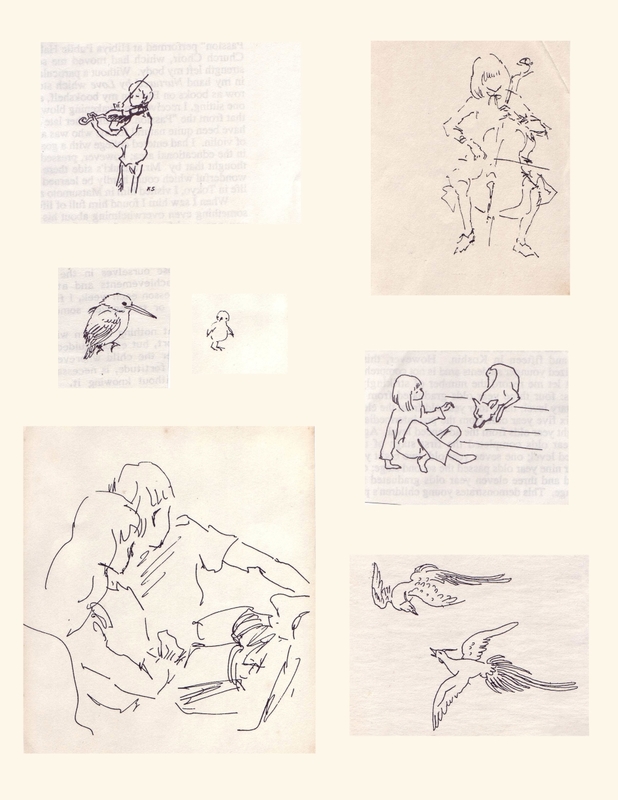

Sketches by Kyoko Selden |

The idea for these two special issues, first proposed by Noriko Mizuta and realized with the editorial expertise of Miya Elise Mizuta, was made possible with the help of many people with whom Kyoko collaborated. We are grateful to the Review of Japanese Culture and Society for allowing the reprint of selected texts, and we encourage Asia-Pacific Journal readers to peruse the journal issue, portions of which are included here. We are indebted to Lili Selden and Hiroaki Sato for their literary, translational, and editorial expertise throughout the entire process of preparing Kyoko’s translations for publication. Their contributions are particularly notable in the translations of the Hinin Taiheiki, renga by Dōyo, haiku by Mitsuhashi, and the introductions to these selections. Joan Piggott was generous with her knowledge of the Taiheiki and renga, among other areas. Miya Elise Mizuta, Noriko Mizuta, and members the editorial staff of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society—Professor Haga Kōichi (Assistant Editor), Natta Phisphumvidhi (Production Editor), Tajima Miho (Editorial Editor), and Nara Hiroe—facilitated all aspects of publication of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society issue. At the Asia-Pacific Journal, Alex Bueno, Kienan Knight-Boehm, and Emilie Takayama provided able technical support. We also appreciate support from the Jōsai International Center for the Promotion of Art and Science.

Notes

The 2015 special issue (Volume XXVII) of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society, published in English by the Jōsai International Center for the Promotion of Art and Science at Jōsai University, includes a complete translation of Osaki Midori’s novella Wanderings in the Realm of the Seventh Sense and Uehara Noboru’s short story “Our Gang Age,” 1970), among other literary works not reprinted here, and writings by Noriko Mizuta, Brett de Bary, Arthur Groos, and Akira Iriye. Interspersed are Kyoko’s photographs, artworks, and original poems, providing glimpses of her rich personal life and artistic range and sensibility.

In these special issues, some translators and authors have chosen to transcribe Chinese words in Wade-Giles, while others have used Pinyin. We have maintained the use of both romanization systems as the translators have suggested.