For almost two centuries American government, though always imperfect, was also a model for the world of limited government, having evolved a system of restraints on executive power through its constitutional arrangement of checks and balances.

Since 9/11 however, constitutional practices have been overshadowed by a series of emergency measures to fight terrorism. The latter have mushroomed in size, reach and budget, while traditional government has shrunk. As a result we have today what the journalist Dana Priest has called two governments: the one its citizens were familiar with, operated more or less in the open: the other a parallel top secret government whose parts had mushroomed in less than a decade into a gigantic, sprawling universe of its own, visible to only a carefully vetted cadre – and its entirety…visible only to God.1

More and more, it is becoming common to say that America, like Turkey before it, now has what Marc Ambinder and John Tirman have called a deep state behind the public one.2 And this parallel government is guided in surveillance matters by its own Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, known as the FISA court, which according to the New York Times, “has quietly become almost a parallel Supreme Court.”3 Thanks largely to Edward Snowden, it is now clear that the FISA Court has permitted this deep state to expand surveillance beyond the tiny number of known and suspected Islamic terrorists, to any incipient protest movement that might challenge the policies of the American war machine.

Americans have by and large not questioned this parallel government, accepting that sacrifices of traditional rights and traditional transparency are necessary to keep us safe from al-Qaeda attacks. However secret power is unchecked power, and experience of the last century has only reinforced the truth of Lord Acton’s famous dictum that unchecked power always corrupts. It is time to consider the extent to which American secret agencies have developed a symbiotic relationship with the forces they are supposed to be fighting – and have even on occasion intervened to let al-Qaeda terrorists proceed with their plots.

“Intervened to let al-Qaeda terrorists proceed with their plots”? These words as I write them make me wonder yet again, as I so often do, if I am not losing my marbles, and proving myself to be no more than a zany “conspiracy theorist.” Yet I have to remind myself that my claim is not one coming from theory, but rests on certain undisputed facts about incidents that are true even though they have been systematically suppressed or under-reported in the American mainstream media.

More telling, I am describing a phenomenon that occurred not just once, but consistently, almost predictably. We shall see that, among the al-Qaeda terrorists who were first protected and then continued their activities were

1) Ali Mohamed, identified in the 9/11 Commission Report (p. 68) as the leader of the 1998 Nairobi Embassy bombing;

2) Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, Osama bin Laden’s close friend and financier, while in the Philippines, of Ramzi Yousef (principal architect of the first WTC attack) and his uncle Khalid Sheikh Mohammed;

3) Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, identified in the 9/11 Commission Report (p. 145) as “the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks.”

4) Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, two of the alleged 9/11 hijackers, whose presence in the United States was concealed from the FBI by CIA officers for months before 9/11.4

It might sound from these three citations as if the 9/11 Commission marked a new stage in the U.S. treatment of these terrorists, and that the Report now exposed those terrorists who in the past had been protected. On the contrary, a principal purpose of my essay is to show that

1) one purpose of protecting these individuals had been to protect a valued intelligence connection (the “Al-Qaeda connection” if you will);

2) one major intention of the 9/11 Commission Report was to continue protecting this connection;

3) those on the 9/11 Commission staff who were charged with this protection included at least one commission member (Jamie Gorelick), one staff member (Dietrich Snell) and one important witness (Patrick Fitzgerald) who earlier had figured among the terrorists’ protectors.

In the course of writing this essay, I came to another disturbing conclusion I had not anticipated. This is that a central feature of the protection has been to defend the 9/11 Commission’s false picture of al-Qaeda as an example of non-state terrorism, at odds with not just the CIA but also the royal families of Saudi Arabia and Qatar. In reality, as I shall show, royal family protection from Qatar and Saudi Arabia (concealed by the 9/11 Commission) was repeatedly given to key figures like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged “principal architect of the 9/11 attacks.”

This finding totally undermines the claim that the wars fought by America in Asia since 9/11 have been part of a global “war on terror.” On the contrary, the result of the wars has been to establish a permanent U.S. military presence in the oil- and gas-rich regions of Central Asia, in alliance with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Pakistan – the principal backers of the jihadi terrorist networks the U.S. has been supposedly fighting. Meanwhile the most authentic opponents in the region of these Sunni jihadi terrorists – the governments of Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Iran – have been overthrown by U.S. invasion or military support (in the case of Iraq and Libya) subverted with U.S. support (in the case of Syria), or sanctioned and threatened as part of an “axis of evil” (in the case of Iran).

The protection to terrorists described in this essay, in other words, has been sustained partly in order to support the false premises that have underlain U.S. Asian wars for more than a decade. And the blame cannot be assigned all to the Saudis. Two months before 9/11, FBI counterterrorism expert John O’Neill described to the French journalist Jean-Charles Brisard America’s “impotence” in getting help from Saudi Arabia concerning terrorist networks. The reason? In Brisard’s paraphrase, “Just one: the petroleum interests.”5 Former CIA officer Robert Baer voiced a similar complaint about the lobbying influence of “the Foreign Oil Companies Group, a cover for a cartel of major petroleum companies doing business in the Caspian. . . . The deeper I got, the more Caspian oil money I found sloshing around Washington.”6

The decade of protection for terrorists demonstrates the power of this secretive dimension of the American deep state: the dark forces in our society responsible for protecting terrorists, over and above the parallel government institutionalized on and after 9/11.7 Although I cannot securely define these dark forces, I hope to demonstrate that they are related to the black hole at the heart of the complex U.S-Saudi connection, a complex that involves oil majors like Exxon, the military coordination of oil and gas movements from the Persian Gulf and Central Asia, offsetting arms sales, Saudi investments in major U.S. corporations like Citibank and the Carlyle Group, and above all the ultimate United States dependency on Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and OPEC, for the defense of the petrodollar.8

This deeper dimension of the deep state, behind its institutional manifestation in our parallel government, is a far greater threat than foreign terrorism to the preservation of U.S. democracy.

The FBI’s Intervention with the RCMP to Release Ali Mohamed, 1993

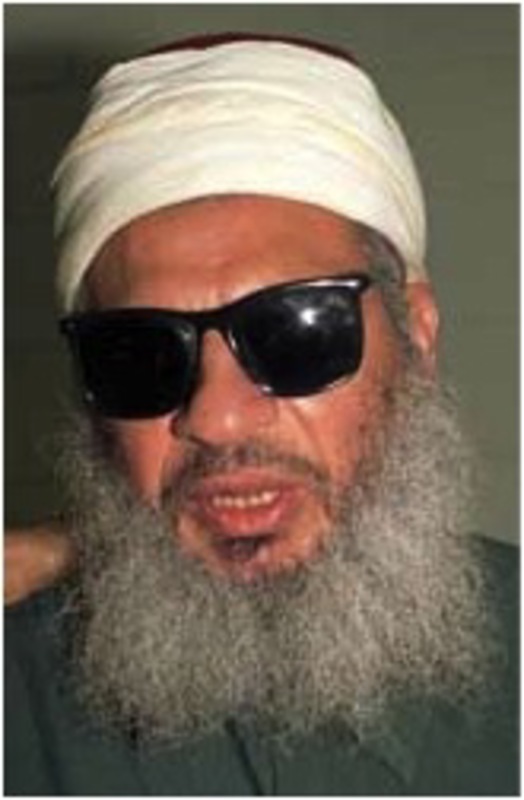

Consider the FBI’s instruction in 1993 to the Canadian RCMP to release the al-Qaeda organizer Mohamed Ali, who then proceeded to Nairobi in the same year to begin planning the U.S. Embassy bombing of 1998.

|

Ali Mohamed |

In early 1993 a wanted Egyptian terrorist named Essam Hafez Marzouk, a close ally of Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, arrived at Canada’s Vancouver Airport and was promptly detained by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). A second terrorist named Mohamed Ali, “the primary U.S. intelligence agent for Ayman al-Zawahiri and Osama bin Laden,” came from California to the airport to meet him; and, not finding him, made the mistake of asking about his friend at the Vancouver airport customs office. As a result the RCMP interrogated Mohamed Ali for two days, but finally released him, even though Ali had clearly come in order to smuggle a wanted terrorist into the United States.9

If the RCMP had detained Mohamed Ali, who was much bigger game than the first terrorist, hundreds of lives might have been saved. After being released, Ali went on to Nairobi, Kenya. There in December 1993 he and his team photographed the U.S. Embassy, and then delivered the photos to Osama bin Laden in Khartoum, leading to the Embassy bombing of 1998.10 Ali later told an FBI agent that at some point he also trained al-Qaeda terrorists in how to hijack airplanes using box cutters.11

The RCMP release of Ali Mohamed was unjustified, clearly had historic consequences, and may have contributed to 9/11. Yet the release was done for a bureaucratic reason: Ali Mohamed gave the RCMP the phone number of an FBI agent, John Zent, in the San Francisco FBI office, and told them, “If they called that number, the agent on the other end of the line would vouch for him.” As Ali had predicted, Zent ordered his release.12

Ali Mohamed was an important double agent, of major interest to more important U.S. authorities than Zent. Although Mohamed was at last arrested in September 1998 for his role in the Nairobi Embassy bombing, the USG still had not sentenced him in 2006; and he may still not have gone to jail.13

The story of his release in Vancouver and its consequences is another example of the dangers of working with double agents. One can never be sure if the agent is working for his movement, for his agency, or – perhaps most likely – for increasing his own power along with that of both his movement and his agency, by increasing violence in the world.14

Ali Mohamed’s Release as a Deep Event Ignored by the U.S. Media

Mohamed’s release in Vancouver was a deep event, by which I mean an event predictably suppressed in the media and still not fully understandable. A whole chapter in my book The Road to 9/11 was not enough to describe Mohamed’s intricate relationships at various times with the CIA, U.S. Special Forces at Fort Bragg, the murder of Jewish extremist Meir Kahane, and finally the cover-up of 9/11 perpetrated by the 9/11 Commission and their witness, U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald (Mohamed’s former prosecutor).15

The deep event is also an example of deep politics, a mixture of intrigue and suppression involving not just a part of the U.S. Government, but also the governing media. To this day (according to a 2013 search of Lexis Nexis) the Vancouver release incident, well covered in Canada’s leading newspaper The Toronto Globe and Mail (December 22, 2001), has never been mentioned in any major American newspaper.

|

More disturbingly, it is not hinted at in the otherwise well-informed books and articles about Ali Mohamed by Steven Emerson, Peter Bergen, and Lawrence Wright.16 Nor is there any surviving mention of it in the best insider’s book about the FBI and Ali Mohamed, The Black Banners, by former FBI agent Ali Soufan (a book that was itself heavily and inexcusably censored by the CIA, after being cleared for publication by the FBI).17

There is no doubt of the FBI’s responsibility for Mohamed’s release, It (along with other FBI anomalies in handling Mohamed) is frankly acknowledged in a Pentagon Internet article on Mohamed:

In early 1993, Mohamed was detained by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) at the Vancouver, Canada airport. He had come to the airport to meet an Egyptian who had arrived from Damascus but was found to be carrying two forged Saudi passports. When Mohamed was about to be arrested as well, he told the RCMP he was collaborating with the FBI and gave them a name and phone number to call to confirm this. The RCMP made the call and Mohamed was released immediately at the request of the FBI. When the FBI subsequently questioned Mohamed about this incident, he offered information about a ring in California that was selling counterfeit documents to smugglers of illegal aliens. This is the earliest hard evidence that is publicly available of Mohamed being an FBI informant.18

Contrast this official candor about the FBI responsibility for Mohamed’s release with the suppression of it in a much longer account of Mohamed (3200 words) by Benjamin Weiner and James Risen in the New York Times:

[In 1993] he was stopped by the border authorities in Canada, while traveling in the company of a suspected associate of Mr. bin Laden’s who was trying to enter the United States using false documents.

Soon after, Mr. Mohamed was questioned by the F.B.I., which had learned of his ties to Mr. bin Laden. Apparently in an attempt to fend off the investigators, Mr. Mohamed offered information about a ring in California that was selling counterfeit documents to smugglers of illegal aliens. 19

A long Wall Street Journal account massages the facts even more evasively:

At about the same time [1993], the elusive Mr. Mohamed popped up again on the FBI radar screen with information that underscored the emerging bin Laden threat. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police questioned Mr. Mohamed in the spring of 1993 after his identification was discovered on another Arab man trying to enter the U.S. from Vancouver — a man Mr. Mohamed identified as someone who had helped him move Mr. bin Laden to Sudan. The FBI located Mr. Mohamed near San Francisco in 1993, where he volunteered the earliest insider description of al Qaeda that is publicly known.20

In 1998, after the Embassy bombings, Mohamed was finally arrested. In the ensuing trial an FBI Agent, Daniel Coleman, entered a court affidavit (approved by prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald) which summarized the Vancouver incident as follows:

In 1993, MOHAMED advised the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) that he had provided intelligence and counter-intelligence training in Afghanistan to a particular individual…. MOHAMED admitted that he had travelled to Vancouver, Canada, in the spring of 1993 to facilitate the entry of that individual into the United States…. MOHAMED further admitted that he and the individual had transported Osama bin Laden from Afghanistan to the Sudan in 1991…. MOHAMED told the RCMP that he was in the process of applying for a job as an FBI interpreter and did not want this incident to jeopardize the application. (In fact, MOHAMED then had such an application pending though he was never hired as a translator.)21

Like the American media, this FBI affidavit suppressed the fact that Mohamed, an admitted ally of Osama bin Laden caught red-handed with another known terrorist, was released on orders from the FBI.

The Two Levels of American History: Official History and Deep History

The whole episode illustrates what has become all too common in recent American history, the way in which secret bureaucratic policies can take priority over the public interest, even to the point of leading to mass murder

(since it contributed at a minimum to the 1998 Embassy bombings, if not also to 9/11). It is also an example of what I mean by the two levels of history in America, We can refer to them as those historical facts officially acknowledged, and those facts officially suppressed; or alternatively as those facts fit to be mentioned in the governing media, and those suppressed by the same media. This leads in turn to two levels of historical narrative: official or archival history, which ignores or marginalizes deep events, and a second level – called deep history by its practitioners or “conspiracy theory” by its critics – which incorporates them. The method of deep political research is to recover deep events from this second level.

This activity sets deep political research at odds with the governing media, but not, I believe with the national interest. Speaking personally as an ex-diplomat, I should state clearly that the national interest does occasionally require secrets, at least for a time. Kissinger’s trip to China, for example, which led to a normalization of U.S.-Chinese relations, probably required secrecy (at least at the time) in order to succeed.

When insiders and the governing media collaborate in the keeping of a secret, as in the case of the FBI-ordered release of Mohamed, they probably believe that they are protecting, not just the FBI, but national security. However national security in this case was conspicuously not served by the subsequent embassy bombings, let alone by 9/11.

In the glaring gap between these two levels of history is a third level — that of the privileged books about Mohamed – privileged in the sense that they have access to sources denied to others — that give important but selective parts of the truth. This selectivity is not necessarily culpable; it may for example be due to pressure from lawyers representing Saudi millionaires (a pressure I have yielded to myself).22 But cumulatively it is misleading.

I owe a considerable debt in particular to Lawrence Wright’s book, The Looming Tower, which helped expose many problems and limitations in the official account of 9/11. But I see now in retrospect that I, like many others, have been delayed by its selectivity on many matters (including Mohamed’s RCMP release) from developing a less warped understanding of the truth.

The Longer History of FBI and USG Protection for Ali Mohamed

Why did John Zent vouchsafe for Mohamed in 1993, so that the RCMP released him? The explanation of Peter Lance, the best chronicler of the FBI’s culpability in both the first and second WTC attacks, is that Zent did so because Mohamed was already working as his personal informant, “feeding Zent ‘intelligence’ on Mexican smugglers who were moving illegal immigrants into the United States from the South.”23 (FBI agent Cloonan confirms that Mohamed had been working as a local FBI informant since 1992.24) Elsewhere Lance describes Zent as “trusting and distracted,” so that he failed to realize Mohamed’s importance.25

But the FBI’s protection of Ali Mohamed did not begin with Zent. It dated back at least to 1989, when (according to the Pentagon Security bio)

While serving in the Army at Fort Bragg, he traveled on weekends to Jersey City, NJ, and to Connecticut to train other Islamic fundamentalists in surveillance, weapons and explosives. … Telephone records show that while at Fort Bragg and later, Mohamed maintained a very close and active relationship with the Office of Services [Makhtab-al-Khidimat] of the Mujihadeen, in Brooklyn, which at that time was recruiting volunteers and soliciting funds for the jihad against the Soviets in Afghanistan. This was the main recruitment center for the network that, after the Soviets left Afghanistan, became known as al-Qaida….

The FBI observed and photographed Mohamed giving weapons training to a group of New York area residents during four successive weekends in July 1989. They drove from the Farouq Mosque in Brooklyn to a shooting range in Calverton, Long Island, and they fired AK-47 assault rifles, semiautomatic handguns and revolvers during what appeared to be training sessions. For reasons that are unknown, the FBI then ceased its surveillance of the group.26

In the subsequent trial of Mohamed’s trainees and others for bombing the World Trade Center, the defense attorney, Roger Stavis, established that Mohamed was giving the al-Kifah trainees “courses on how to make bombs, how to use guns, how to make Molotov cocktails.” He showed the court that a training manual seized in Nosair’s apartment “showed how to make explosives and some kind of improvised weapons and explosives.”27

So why would the FBI, having discovered terrorist training, then cease its surveillance? Here the Wall Street Journal has what I am sure is the right answer: the FBI ceased surveillance because it somehow determined that the men were training “to help the mujahedeen fighting the Soviet puppet government in Afghanistan.”28 (Note that the mujahedeen were no longer fighting the Soviet army itself, which had been withdrawn from Afghanistan as of March 1989.)

Al-Kifah, Ali Mohamed, the Flow of Arabs to Afghanistan

Afghanistan is indeed the obvious explanation for the FBI’s terminating its videotaping of jihadists from the Brooklyn Al-Kifah Refugee Center. Incorporated officially in 1987 as “Afghan Refugee Services, Inc.,” the Al-Kifah Center “was the recruitment hub for U.S.-based Muslims seeking to fight the Soviets. As many as two hundred fighters were funneled through the center to Afghanistan.”29 More importantly, it was

a branch of the Office of Services [Makhtab-al-Khidimat]. the Pakistan-based organization that Osama bin Laden helped finance and lead and would later become al Qaeda. In fact, it was Mustafa Shalabi, an Egyptian who founded and ran the center, whom bin Laden called in 1991 when he needed help moving to Sudan.30

As we shall see, the Makhtab, created in 1984 to organize Saudi financial support to the foreign “Arab Afghans” in the jihad, was part of a project that had the fullest support of the Saudi, Egyptian, and U.S. Governments. And Ali Mohamed, although he remained in the US Army Reserves until August 1994, was clearly an important trainer in that project, both in Afghanistan and in America.

A privileged account of Mohamed’s career by Peter Bergen, in Holy Wars, Inc., claims that

Ali Mohamed…was an indispensable player in al-Qaeda…. At some point in the early eighties he proffered his services as an informant to the CIA, the first of his several attempts to work for the U.S. government. The Agency was in contact with him for a few weeks but broke off relations after determining he was “unreliable.” That would turn out to be a masterful understatement, as Mohamed was already a member of Egypt’s terrorist Jihad group. After being discharged from the Egyptian Army in 1984, Mohamed [took] a job in the counterterrorism department of Egyptair. The following year he moved to the United States,31

Bergen’s most serious omission here is that Mohamed, though he was on the State Department’s visa watch list, had been admitted to the U.S. in 1984 “on a visa-waiver program that was sponsored by the agency [i.e. CIA] itself, one designed to shield valuable assets or those who have performed valuable services for the country.”32 This should be enough to question the CIA’s account that it found Mohamed “unreliable.” (Later, one of Mohamed’s officers at Fort Bragg was also convinced that Mohamed was “sponsored” by a U.S. intelligence service, “I assumed the CIA.”)33 In addition Bergen omits that, before Mohamed’s brief stint as a formal CIA agent, he had been selected out of the Egyptian army in 1981 for leadership training at Fort Bragg – an important point to which we shall return.34

The FBI’s Cover-Up of Ali Mohamed in the Kahane Murder

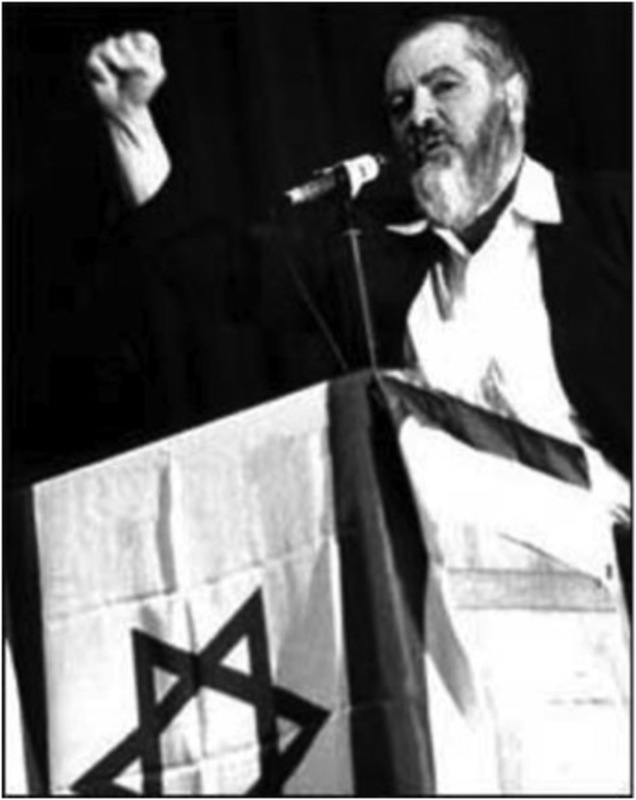

The CIA may have wanted to think that the Al-Kifah training was only for Afghanistan. But the blind Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, the mentor of the Center whom the CIA brought to America in 1990, was preaching for the killing of Jews and also for the destruction of the West.35 His preachings guided Mohamed’s Makhtab trainees: as a first step, in November 1990, three of them conspired to kill Meir Kahane, the founder of the Jewish Defense League.

|

Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman |

Kahane’s actual killer, El Sayyid Nosair, was detained by accident almost immediately, and by luck the police soon found his two coconspirators, Mahmoud Abouhalima and Mohammed Salameh, waiting at Nosair’s house. Also at the house, according to John Miller,

were training manuals from the Army Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg [where Ali Mohamed at the time was a training officer]. There were copies of teletypes that had been routed to the Secretary of the Army and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.36

And the Pentagon bio, with yet another gentle dig at the FBI, identifies the documents as Mohamed’s:

In a search of Nosair’s home, the police found U.S. Army training manuals, videotaped talks that Mohamed delivered at the JFK Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, operational plans for joint coalition exercises conducted in Egypt, and other materials marked Classified or Top Secret. These documents belonged to Mohamed, who often stayed in New Jersey with Nosair. The documents did not surface during Nosair’s 1991 trial for the Kahane murder. It is not known if the FBI investigated Mohamed in connection with these documents.

Yet only hours after the killing, Joseph Borelli, the chief of NYPD detectives, pronounced Nosair a “lone deranged gunman.”37 A more extended account of his remarks in the New York Times actually alluded to Mohamed, though not by name, and minimized the significance of the links to terrorism in a detailed account of the Nosair home cache:

The files contained articles about firearms and explosives apparently culled from magazines, like Soldier of Fortune, appealing to would-be mercenaries. But the police said the handwritten papers, translated by an Arabic-speaking officer, appeared to be minor correspondence and did not mention terrorism or outline any plan to kill the militant Jewish leader who had called for the removal of all Arabs from Israel.

“There was nothing [at Nosair’s house] that would stir your imagination,” Chief Borelli said…. A joint anti-terrorist task force of New York City police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation has been set up to look into any possible international links to the slaying, the official said, but so far has not turned up anything.

“Nothing has transpired that changes our opinion that he acted alone,” Chief Borrelli told a news conference yesterday afternoon.38

|

Meir Kahane |

Later an FBI spokesman said the FBI also believed “that Mr. Nosair had acted alone in shooting Rabbi Kahane.” “The bottom line is that we can’t connect anyone else to the Kahane shooting,” an FBI agent said.39

Blaming the New York County District Attorney, Robert Morgenthau, the FBI later claimed that the evidence retrieved from Nosair’s home was not processed for two or three years.40 But Robert Friedman suggests that the FBI were not just lying to the public, but also to Morgenthau (who had just helped expose and bring down the CIA-favored Muslim bank BCCI).

According to other sources familiar with the case, the FBI told District Attorney Robert M. Morgenthau that Nosair was a lone gunman, not part of a broader conspiracy; the prosecution took this position at trial and lost, only convicting Nosair of gun charges. Morgenthau speculated the CIA may have encouraged the FBI not to pursue any other leads, these sources say. ‘The FBI lied to me,’ Morgenthau has told colleagues. ‘They’re supposed to untangle terrorist connections, but they can’t be trusted to do the job.’41

Using evidence from the Nosair trial transcript, Peter Lance confirms the tension between Morgenthau’s office, which wanted to pursue Nosair’s international terrorist connections, and the FBI, which insisted on trying Nosair alone.42

The FBI’s Protection of Ali Mohamed in the 1993 WTC Bombing

In thus limiting the case, the police and the FBI were in effect protecting, not just Ali Mohamed, but also Nosair’s two Arab coconspirators, Mahmoud Abouhalima and Mohammed Salameh, in the murder of a U.S. citizen. The two were thus left free to kill again on February 26, 1993, one month after the FBI secured Mohamed’s release in Vancouver. Both Abouhalima and Salameh were ultimately convicted in connection with the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, along with another Mohamed trainee, Nidal Ayyad.

To quote the Pentagon bio yet again,

In February 1993, the terrorist cell that Mohamed had trained exploded a truck bomb under the World Trade Center that killed six and injured about 1,000 persons. The perpetrators of this bombing included people Mohamed had trained, and Mohamed had been in close contact with the cell during the period leading up to the bombing [i.e. including January 1993, the month of Mohamed’s detention and release in Vancouver]. Mohamed’s name appeared on a list of 118 potential un-indicted co-conspirators that was prepared by federal prosecutors.

Ali Mohamed was again listed as one of 172 unindicted co-conspirators in the follow-up “Landmarks” case, which convicted Sheikh Rahman and others of plotting to blow up the United Nations, the Lincoln and Holland tunnels, and the George Washington Bridge.43 The two cases were closely related, as much of the evidence for the Landmarks case came from an informant, Emad Salem, whom the FBI had first planted among the WTC plotters. But the prosecutors’ awareness of Ali Mohamed’s involvement must be contrasted with the intelligence failure at the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center: according to Steve Coll, the CTC “immediately established a seven-day, twenty-four hour task force to collect intelligence about the World Trade Center bombing…but nothing of substance came in.”44

In the WTC bombing case, the FBI moved swiftly to bring the Al-Kifah plotters to trial one month later, in March. Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, a DIA officer, later said that

we [i.e. DIA] were surprised how quickly they’d [i.e. FBI] made the arrests after the first World Trade Center bombing. Only later did we find out that the FBI had been watching some of these people for months prior to both incidents [i.e. both the 1993 WTC bombing and 9/11].45

Shaffer’s claim that the FBI had been watching some of the plotters is abundantly corroborated, e.g. by Steve Coll in Ghost Wars.46

The U.S., Egyptian, and Saudi Backing for the Makhtab Network

What was being protected here by the FBI? One obvious answer is an extension of Lance’s explanation for Zent’s behavior: that Mohamed had already been a domestic FBI informant since 1992. However I entirely agree with New York County District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, who suspected that a much larger asset was being protected, the Saudi-sponsored network which we now know was the Makhtab-i-Khidimat, by this time already evolving into al-Qaeda.

On the day the FBI arrested four Arabs for the World Trade Centre bombing, saying it had all of the suspects, Morgenthau’s ears pricked up. He didn’t believe the four were ‘self-starters,’ and speculated that there was probably a larger network as well as a foreign sponsor. He also had a hunch that the suspects would lead back to Sheikh Abdel Rahman. But he worried [correctly] that the dots might not be connected because the U.S. government was protecting the sheikh for his help in Afghanistan.47

This “larger network” of the Makhtab, although created in 1984, consolidated an assistance program that had been launched by the U.S. government much earlier, at almost the beginning of the Afghan war itself.

In January 1980, Brzezinski visited Egypt to mobilize support for the jihad. Within weeks of his visit, Sadat authorized Egypt’s full participation, giving permission for the U.S. Air Force to use Egypt as a base…and recruiting, training, and arming Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood activists for battle…. Not only were they packaged and shipped to Afghanistan, but [by the end of 1980] they received expert training from U.S. Special Forces.48

U.S. military trainers had in fact already been in Egypt since at least 1978 (the year of the Israel-Egypt Camp David peace accords), training Sadat’s elite praetorian guard, of which Mohamed Ali was at the time a member. At first the training was handled by a “private” firm, J.J. Cappucci and Associates, owned by former CIA officers Ed Wilson and Theodore Shackley. But after Brzezinski’s visit in 1980, the contract was taken over by the CIA.49

In 1981 Ali Mohamed was selected out of the U.S.-trained praetorian guard for four months of Special Forces training at Fort Bragg: “Working alongside Green Berets, he learned unconventional warfare, counterinsurgency operations, and how to command elite soldiers on difficult missions.”50 The leadership aspect of this training almost certainly means that Mohamed was part of the Pentagon’s Professional military education (PME) program for future leaders; and that he was being trained to transmit to Egypt the kind of Afghanistan-related skills that he later provided to Al-Kifah on Long Island in 1989.

Mohamed was thus in America when some of his fellow guard members, responding to a fatwa or religious order from Muslim Brotherhood member Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, assassinated Sadat in October 1981. The assassination only accelerated the export to Afghanistan of Muslim Brotherhood members accused of the murder. These included two of Mohamed’s eventual close associates, Sheikh Abdel Rahman and Rahman’s then friend Ayman al-Zawahiri, to whom Mohamed swore a bayat or oath of allegiance in 1984, after his return to Egypt.51

The Al-Kifah Target in 1993: Not Afghanistan but Bosnia

Morgenthau’s suspicions about Afghanistan in 1993 were very pertinent, but also somewhat anachronistic; by 1993, under its new director James Woolsey, the CIA had lost interest in Afghanistan. The new interim president of Afghanistan, Mojaddedi, under pressure from Washington, announced that the Arab Afghans should leave. Pakistan followed suit, closed the offices of all mujahedin in its country, and ordered the deportation of all Arab Afghans.52 But the Al-Kifah support network had new targets in mind elsewhere.

After 1991 the Al-Kifah center was focused chiefly on training people for jihad in Bosnia, and at least two sources allege that Ali Mohamed himself visited Bosnia in 1992 (when he also returned to Afghanistan).53

Al-Kifah’s English-language newsletter Al-Hussam (The Sword) also began publishing regular updates on jihad action in Bosnia….Under the control of the minions of Shaykh Omar Abdel Rahman, the newsletter aggressively incited sympathetic Muslims to join the jihad in Bosnia and Afghanistan themselves….The Al-Kifah Bosnian branch office in Zagreb, Croatia, housed in a modern, two-story building, was evidently in close communication with the organizational headquarters in New York. The deputy director of the Zagreb office, Hassan Hakim, admitted to receiving all orders and funding directly from the main United States office of Al-Kifah on Atlantic Avenue controlled by Shaykh Omar Abdel Rahman.54

One of Ali Mohamed’s trainees at al-Kifah, Rodney Hampton-El, assisted in this support program, recruiting warriors from U.S. Army bases like Fort Belvoir, and also training them to be fighters in New Jersey.55 In 1995 Hampton-El was tried and convicted for his role (along with al-Kifah leader Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman) in the plot to blow up New York landmarks. At the trial Hampton-El testified how he was personally given thousands of dollars for this project by Saudi Prince Faisal in the Washington Saudi Embassy.56 (In addition, “Saudi intelligence has contributed to Sheikh Rahman’s legal-defence fund, according to Mohammed al-Khilewi, the former first secretary to the Saudi mission at the U.N.)”57

Al-Kifah, Al-Qaeda, Tajikistan, and Drugs

Meanwhile the ISI had not lost interest in bin Laden’s Arabs, but began to recruit them with bin Laden’s support for battle in new areas, notably Kashmir.58 Bin Laden in the same period began to dispatch his jihadis into areas of the former Soviet Union, notably to the infant Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) in Tajikistan.

The outbreak of Islamist violence in Tajikistan…moved bin Laden to send a limited number of Al-Qaeda cadre to support Tajik Islamist forces, among them his close associate Wali Khan Amin Shah [an Uzbek later working in the Philippines with Ramzi Yousuf and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed] and the soon-to-be-famous mujahid, Ibn Khattab. In addition, bin Laden, even after his 1991 move to Sudan, continued to run training camps in Afghanistan, where he welcomed the chance to train Tajiks, Uzbeks, Uighurs, and Chechens.59

In an al-Qaeda document captured in Iraq, bin Laden wrote

with the grace of Allah, we were successful in cooperating with our brothers in Tajikistan in various fields including training. We were able train a good number of them, arm them and deliver them to Tajikistan. Moreover, Allah facilitated to us delivering weapons and ammunition to them; we pray that Allah grants us all victory60

Many other accounts report that the delivery of arms and ammunition was facilitated by the involvement of the IMU and bin Laden in the massive flow of heroin from Afghanistan into the former Soviet Union. According to Ahmed Rashid,

Much of the I.M.U.’s financing came from the lucrative opium trade through Afghanistan. Ralf Mutschke, the assistant director of Interpol’s Criminal Intelligence Directorate, estimated that sixty per cent of Afghan opium exports were moving through Central Asia and that the “I.M.U. may be responsible for seventy per cent of the total amount of heroin and opium transiting through the area.”61

Among the experts confirming the IMU-al-Qaeda-drug connection is Gretchen Peters,

The opium trade… supported the global ambitions of Osama bin Laden…. There was … evidence that bin Laden served as middleman between the Taliban and Arab drug smugglers…. With Mullah Omar’s approval, bin Laden hijacked the state-run Ariana Airlines, turning it into a narco-terror charter service… according to former U.S. and Afghan officials…. One U.S. intelligence report seen by the author described a smuggling route snaking up through Afghanistan’s northwest provinces if Baghdis, Faryab, and Jowzan into Turkmenistan. It was being used as of mid-2004 by “extremists associated with the Taliban, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and al-Qaeda,” the report said. Traffickers would move “both heroin and terrorists” along the route and “then onwards into other countries in Central Asia,” the CIA document said.62

It has been widely reported that in the early 1990s, as US financial support dwindled and bin Laden’s finances were being rapidly exhausted in Sudan, his new involvement with the IMU and later the Taliban involved al-Qaeda also in the growing Afghan heroin traffic. Peters saw a CIA document confirming this.63 Yet the 9/11 Report, in contorted language, denied this, as did a Staff Report:

No persuasive evidence exists that al Qaeda relied on the drug trade as an important source of revenue, had any substantial involvement with conflict diamonds, or was financially sponsored by any foreign government.64

This surprising claim was at odds with the views of many U.S. intelligence operatives. It also contradicted the official position of the British government, which told its Parliament in 2001,

Usama Bin Laden and Al Qaida have been based in Afghanistan since 1996, but have a network of operations throughout the world. The network includes training camps, warehouses, communication facilities and commercial operations able to raise significant sums of money to support its activity. That activity includes substantial exploitation of the illegal drugs trade from Afghanistan.65

And there were allegations that the Brooklyn Al-Kifah Center, as well as bin Laden, was involved in drug trafficking. Back in 1993, the New York Times reported that, according to investigators, “Some of the 11 men charged in the [Day of Terror] plot to bomb New York City targets are also suspected of trafficking in drugs.”66 Mujahid Abdulqaadir Menepta, a Muslim suspect in both the 9/11 case and the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, was linked by telephone numbers on his cell phones to ongoing criminal investigations, involving “organized crime, drugs, and money laundering.”67 And Raed Hijazi, an al Qaeda terrorist arrested in Jordan in 1999, had previously become an FBI informant in order to avoid drug charges.68

Was the U.S. Protection of the Al-Kifah Center Intended to Help Export Jihadis?

There is also no treatment in the 9/11 Report, and almost none elsewhere, of the allegations from Steven Emerson that by 1987, the Al-Kifah Center Al-Farooq Mosque in Brooklyn “had become a center for counterfeiting tens of thousands of dollars.”69 Similarly there has been no government follow-up of the allegation by Yossef Bodansky, citing FBI informant Emad Salem, that one of the Al-Kifah cell leaders (Siddiq Ibrahim Siddig Ali)

had offered to sell a million dollars [of counterfeit currency] for $150,000, well below market value. … Quantities of counterfeit $100 bills were later found at the apartment of Sheikh Umar Abdel-Rahman.70

J.M. Berger goes further, reporting from court testimony: “In order to support Al Kifah’s operations,” Mustafa Shalabi, the head of the Al-Kifah Center until his murder in 1991, “employed a number of for-profit criminal enterprises, including gunrunning, arson for hire, and a counterfeiting ring set up in the basement of the jihad office.”71 Yet the 9/11 Report is silent about these serious charges, which U.S. prosecutors at the time did not pursue.

Why this official reticence? The answer may lie in the fact that by 1996 bin Laden was “supporting Islamists in Lebanon, Bosnia, Kashmir, Tajikistan, and Chechnya.”72 And in step with bin Laden, the al-Kifah Center was also supporting jihad after 1992 “in Afghanistan, Bosnia, the Philippines, Egypt, Algeria, Kashmir, Palestine, and elsewhere.”73

But bin Laden and Al-Kifah were not acting on their own, they were supporting projects, especially in Tajikistan (1993-95) and then Chechnya (after 1995), where their principal ally, Ibn al-Khattab (Thamir Saleh Abdullah Al-Suwailem) also enjoyed high-level support in Saudi Arabia.74

Khattab enjoyed a certain amount of logistical and financial support from Saudi Arabia. Saudi sheikhs declared the Chechen resistance a legitimate jihad, and private Saudi donors sent money to Khattab and his Chechen colleagues. As late as 1996, mujahidin wounded in Chechnya were sent to Saudi Arabia for medical treatment, a practice paid for by charities and tolerated by the state.75

Ali Soufan adds that America also supported this jihad: by 1996, “the United States had been on the side of Muslims in Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Chechnya.”76

By protecting the Al-Kifah Center and its associates (including Mohamed) and not prosecuting them for their crimes (including murder), the U.S. Government was in effect keeping open a channel whereby those in America who wished to wage jihad were helped to wage jihad in other countries, not here. (After the arrest of Sheikh Rahman in 1993 the Al Kifah closed itself down. But we shall see that an allied institution, Sphinx Trading, continued to be protected, even after the FBI knew it had helped one of the alleged 9/11 hijackers prepare for 9/11.)

Was all this protection intended to keep just such a channel open? It was certainly an intentional result of the protection and support for the Makhtab al-Khidimat in Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Support for the Makhtab, and Later for Al Qaeda

The Saudis, like the Egyptians, had domestic reasons for wishing to export as many Muslim Brotherhood members to possible death in Afghanistan, Bosnia, or anywhere else. Until 1979 Saudi Arabia had provided a home to Brotherhood members fleeing persecution in countries like Syria and Egypt, where some of them had tried to assassinate the Saudis’ political enemy Gamel Abdel Nasser. But in 1979 radical Wahhabis, condemning the ruling Saudi family as corrupt infidels, seized the Grand Mosque at Mecca and defended it for weeks.77 Profoundly shaken, the Saudi family used its foundations, like the World Muslim League (WML), to subsidize the emigration of political Islamists, above all to the new jihad in Afghanistan, which opened one month later against the Soviet Union.78

In Afghanistan both Rahman and al-Zawahiri worked with the Makhtab al Khidamat that had been created in 1984 by two other members of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Palestinian Abdullah Azzam and the Saudi Osama bin Laden.79 All that the 9/11 Commission Report has to say about the Makhtab’s financing is that “Bin Laden and his comrades had their own sources of support and training, and they received little or no assistance from the United States” (p. 56). But the Pakistani author Ahmed Rashid makes clear the support coming from the Saudi royal family, including Prince Turki (the head of Saudi intelligence), and also royal creations like the World Muslim League:

Bin Laden, although not a royal, was close enough to the royals and certainly wealthy enough to lead the Saudi contingent. Bin Laden, Prince Turki and General [Hameed] Gul [the head of the Pakistani ISI] were to become firm friends and allies in a common cause. The center for the Arab-Afghans was the offices of the World Muslim League and the Muslim Brotherhood in Peshawar which was run by Abdullah Azam. Saudi funds flowed to Azam and the Makhtab al Khidamat or Services Center which he created in 1984 to service the new recruits and receive donations from Islamic charities. Donations from Saudi Intelligence, the Saudi Red Crescent, the World Muslim League and private donations from Saudi princes and mosques were channeled through the Makhtab. A decade later the Makhtab would emerge at the center of a web of radical organizations that helped carry out the World Trade Center bombing [in 1993] and the bombings of US Embassies in Africa in 1998.80

Former Ambassador Peter Tomsen has described how the evolution of the Makhtab into al-Qaeda was accomplished with support from the offices of royally ordained organizations like the World Muslim League (WML) and the World Assembly of Muslim Youth (WAMY):

Bin Laden’s brother-in-law, Mohammad Jamal Khalifa, headed the Muslim World League office in Peshawar during the mid-1980s. In 1988, he moved to Manila and opened a branch office of the World Assembly of Muslim Youth. He made the charity a front for bin Laden’s terrorist operations in the Philippines and Asia. Al Qaeda operatives, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, and his nephew Ramzi Yusuf [master bomb-maker of the 1993 WTC bombing], traveled to Manila in the early 1990s to help Khalifa strengthen al-Qaeda networks in Southeast Asia and plan terrorist attacks in the region.81

There are many other examples of WML and WAMY connections to Al-Qaeda. For example Maulana Fazlur Rehman Khalil, a signatory of Osama bin Laden’s 1998 fatwa to kill Jews and Americans, was invited in 1996 to the 34th WML Congress in Mecca and also spoke there to WAMY.82 Yet there are only minimal references to Maulana Fazlur Rehman in the western (as opposed to the Asian) media, and none (according to a Lexis Nexis search in July 2013) linking him to the WML or WAMY.

The FBI’s hands-off attitude towards WAMY in America may help explain its protection of Ali Mohamed. According to former federal prosecutor John Loftus and others, there was a block in force in the 1980s against antiterrorism actions that might embarrass the Saudis.83 This block explains for example the protection enjoyed by the chair of WAMY in Virginia, Osama bin Laden’s nephew Abdullah bin Laden. The FBI opened an investigation of Abdullah bin Laden in February 1996, calling WAMY “a suspected terrorist organization,” but the investigation was closed down six months later.84

How and Why Did a Passportless Osama Leave Saudi Arabia?

None of the official or privileged sources on Ali Mohamed has linked him to Saudi intelligence activities. But there is at least one such link, his trip, as described in the Coleman FBI affidavit, when he “travelled to Afghanistan to escort Usama bin Laden from Afghanistan to the Sudan.”85 The FBI affidavit presents this, without explanation, as an act in furtherance of an al-Qaeda “murder conspiracy.” But Osama’s move to Sudan was synchronized with a simultaneous investment in Sudan by his bin Laden brothers, including an airport construction project that was largely subsidized by the Saudi royal family.86

A great deal of confusion surrounds the circumstances of bin Laden’s displacement in 1991-92, from Saudi Arabia via Pakistan (and perhaps Afghanistan) to the Sudan. But in these conflicted accounts one fact is not contested: bin Laden’s trip was initially arranged by someone in the royal family.87 Steve Coll in Ghost Wars reports that this person was Saudi intelligence chief Prince Turki, who blamed it on pressure from the U.S:

Peter Tomsen and other emissaries from Washington discussed the rising Islamist threat with [Saudi intelligence chief] Prince Turki in the summer of 1991…. At some of the meetings between Turki and the CIA, Osama bin Laden’s name came up explicitly. The CIA continued to pick up reporting that he was funding radicals such as Hekmatyar in Afghanistan…. “His family has disowned him,” Turki assured the Americans about bin Laden. Every effort had been made to persuade bin Laden to stop protesting against the Saudi royal family. These efforts had failed, Turki conceded, and the kingdom was now prepared to take sterner measures…. Bin Laden learned of this when Saudi police arrived at his cushion-strewn, modestly furnished compound in Jeddah to announce that he would have to leave the kingdom. According to an account later provided to the CIA by a source in Saudi intelligence, the officer assigned to carry out the expulsion assured bin Laden that this was being done for his own good. The officer blamed the Americans. The U.S. government was planning to kill him, he told bin Laden, by this account, so the royal family would get him out of the kingdom for his own protection. The escort put bin Laden on a plane out of Saudi Arabia.88

Coll’s magisteral but privileged book appeared in February 2004. Six months later the 9/11 Commission Report published a quite different account, implying that by 1991 the Saudi government was estranged from bin Laden:

The Saudi government… undertook to silence Bin Laden by, among other things, taking away his passport. With help from a dissident member of the royal family, he managed to get out of the country under the pretext of attending an Islamic gathering in Pakistan in April 1991.89

Lawrence Wright claims that the prince returning Osama’s passport was Interior Minister Prince Naif, after bin Laden persuaded him he was needed in Peshawar “in order to help mediate the civil war among the mujahideen.”90 Prince Naif, the most anti-American of the senior Saudi royals, gave back bin Laden’s passport on one condition, that he “sign a pledge that he would not interfere with the politics of South Arabia or any Arab country.”91

The “Islamic gathering” is almost certainly a reference to the on-going negotiations in Peshawar which eventually produced the Saudi-backed Peshawar Accord (finalized in April 1992) to end the Afghan Civil War. By several well-informed accounts, Bin Laden did play an important part in these negotiations, in furtherance (I would argue) of Prince Turki’s own policies. Like Sheikh Rahman before him in 1990, bin Laden tried, vainly, to negotiate a truce between the warring mujahideen leaders, Massoud and Hekmatyar. In these negotiations (according to Peter Tomsen, who was there), Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, the Muslim Brotherhood and al-Qaeda were all united in seeking the same objective: a united Sunni army that (in opposition to American appeals for Shia representation) that could retake Kabul by force.92

Thus I believe it is quite clear that bin Laden, in his mediation attempts to bring Hekmatyar into the Peshawar consensus, was acting in line with official Saudi and Pakistani interests. Others disagree. Without documentation, the author of the Frontline biography of bin Laden asserts,

Contrary to what is always reiterated bin Laden has never had official relations with the Saudi regime or the royal family. All his contacts would happen through his brothers. [As noted above, Ahmed Rashid claims that bin Laden and Prince Turki became “firm friends and allies” (Taliban, 131).] Specifically he had no relation with Turki al-Faisal head of Saudi intelligence. He used to be very suspicious of his role in Afghanistan and once had open confrontation with him in 1991 and accused him of being the reason of the fight between Afghan factions.93

Michael Scheuer, once head of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center, endorsed this claim, and reinforced it with the testimony of Sa’ad al-Faqih (a critic of the Saudi royal family who has been accused by the U.S. Treasury of being affiliated with al-Qaeda) that, “after the Soviets withdrew ‘Saudi intelligence [officers] were actually increasing the gap between Afghani factions to keep them fighting.’”94

But this claim if true must have been after Kabul fell to the jihadis in 1992, when Massoud, backed by the favored Saudi client Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, began to fight Hekmatyar, the favored client of Pakistan’s ISI. Before this time the U.S. State Department’s Afghan policy was to promote a broad-based opposition to the rump Communist government in Kabul, while “side-lining the extremists,” including both Hekmatyar and Sayyaf,95 Pakistan’s ISI in the same period clearly wanted a strong rebel alliance united behind Hekmatyar, and both the CIA and the Saudis agreed. As Barnett Rubin reports, “During this period, political ‘unity’ of some sort among the mujahidin groups was a major goal of U.S.-Pakistani-Saudi policy.”96

|

Hekmatyar |

I conclude that bin Laden’s mediation efforts in Peshawar in 1991 were in accordance with Prince Turki’s preferences, as were also Ali Mohamed’s efforts, in organizing bin Laden’s subsequent move from Afghanistan and Pakistan to the Sudan. As Steve Coll reports, the break between bin Laden and the Saudi royal family did not become serious until 1993, after the involvement of bin Laden’s ally Sheikh Rahman in the first WTC bombing.97

As noted above, Ahmed Rashid claims that bin Laden and Prince Turki became “firm friends and allies” in the same cause (Taliban, 131).

Meanwhile Saudi royal support for this web of radical organizations, in which Ali Mohamed was a central organizer and trainer, continued until at least 1995, well after the WTC bombing of 1993. Anthony Summers reports that Turki may have personally renewed a deal with bin Laden as late as 1998:

In sworn statements after 9/11, former Taliban intelligence chief Mohammed Khaksar said that in 1998 the prince sealed a deal under which bin Laden undertook not to attack Saudi targets. In return, Saudi Arabia would provide funds and material assistance to the Taliban…. Saudi businesses, meanwhile, would ensure that money also flowed directly to bin Laden. Turki would deny after 9/11 that any such deal was done with bin Laden. One account has it, however, that he himself met with bin Laden – his old protégé from the days of the anti-Soviet jihad – during the exchanges that led to the deal.98

In 1991 the Soviet troops had been out of Kabul for two years; and, as former US Ambassador Tomsen has reported, the CIA’s objective of a Pakistan-backed military overthrow in Kabul was at odds with the official U.S. policy of support for “a political settlement restoring Afghanistan’s independence.”99 Ambassador Tomsen himself told the CIA Station Chief in Islamabad (Bill) that, by endorsing Pakistan’s military attack on Kabul,

he was violating fundamental U.S. policy precepts agreed to in Washington by his own agency. American policy was to cut Hekmatyar off, not build him up. Bill looked at me impassively as I spoke. I assumed his superiors in Langley had approved the offensive. The U.S. government was conducting two diametrically opposed Afghan policies.100

Steve Coll agrees that “By early 1991, the Afghan policies pursued by the State Department and the CIA were in open competition with each other…. The CIA…continued to collaborate with Pakistani military intelligence on a separate military track that mainly promoted Hekmatyar and other Islamist commanders.”101

This conflict between the State Department and CIA was far from unprecedented. In particular it recalled the CIA-State conflict in Laos in 1959-60, which led to a tragic war in Laos, and eventually Vietnam.102 Just as oil companies had a stake in that conflict, so too in 1990-92 the CIA was thinking not just of Afghanistan but of the oil resources of Central Asia, where some of the al-Kifah-trained “Arab Afghans” were about to focus their attention.

The State Department in Afghanistan represented the will of the National Security Council and the public state. The CIA, on the other hand, was not “rogue” (as has sometimes been suggested). It was pursuing the goals of oil companies and their financial backers – or what I have called the deep state — in preparing for a launch into the former Soviet republics of central Asia.

In 1991 the leaders of Central Asia “began to hold talks with Western oil companies, on the back of ongoing negotiations between Kazakhstan and the US company Chevron.”103 The first Bush Administration actively supported the plans of U.S. oil companies to contract for exploiting the resources of the Caspian region, and also for a pipeline not controlled by Moscow that could bring the oil and gas production out to the west.

In the same year 1991, Richard Secord, Heinie Aderholt, and Ed Dearborn, three veterans of U.S. operations in Laos, and later of Oliver North’s operations with the Contras, turned up in Baku under the cover of an oil company, MEGA Oil.104 This was at a time when the first Bush administration had expressed its support for an oil pipeline stretching from Azerbaijan across the Caucasus to Turkey.105 MEGA never did find oil, but did contribute materially to the removal of Azerbaijan from the sphere of post-Soviet Russian influence.

As MEGA operatives in Azerbaijan, Secord, Aderholt, Dearborn, and their men engaged in military training, passed “brown bags filled with cash” to members of the government, and above all set up an airline on the model of Air America which soon was picking up hundreds of mujahedin mercenaries in Afghanistan.106 (Secord and Aderholt claim to have left Azerbaijan before the mujahedin arrived.) Meanwhile, Hekmatyar, who at the time was still allied with bin Laden, was “observed recruiting Afghan mercenaries [i.e. Arab Afghans] to fight in Azerbaijan against Armenia and its Russian allies.”

Meanwhile, Hekmatyar, who at the time was still allied with bin Laden, was “observed recruiting Afghan mercenaries [i.e. Arab Afghans] to fight in Azerbaijan against Armenia and its Russian allies.”107 Hekmatyar was a notorious drug trafficker; and, at this time, heroin flooded from Afghanistan through Baku into Chechnya, Russia, and even North America.108

Bin Laden, Ali Mohamed, and the Saudi Royal Family

By attempting to negotiate Hekmatyar’s reconciliation with the other Peshawar commanders, bin Laden in 1991 was clearly an important part of this CIA effort. So, a year earlier, had been the blind Sheikh Omar Abdul Rahman:

In 1990, after the assassination of Abdullah Azzam, Abd al-Rahman was invited to Peshawar, where his host was Khalid al-Islambouli, brother of one of the assassins of Sadat…. On this trip, reportedly paid for by the CIA, Abd al-Rahman preached to the Afghans about the necessity of unity to overthrow the Kabul regime.109

This presumably was shortly before Sheikh Abdul Rahman, even though he was on a State Department terrorist watch list after being imprisoned for the murder of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, was issued a multiple-entry U.S. visa in 1990 “by a CIA officer working undercover in the consular section of the American embassy in Sudan.”110 This was the same CIA-sponsored program that six years earlier had admitted Ali Mohamed, “a visa-waiver program that was … designed to shield valuable assets or those who have performed valuable services for the country.”111

And Ali Mohamed himself was, according to the New York Times, part of the CIA’s plan for a military solution: “In the fall of 1992, Mr. Mohamed returned to fight in Afghanistan, training rebel commanders in military tactics, United States officials said.”112

Before this, Mohamed had been charged with the major task of moving bin Laden, his four wives, and his seventeen children from Afghanistan to Sudan. The task was a major one, for Osama moved with his assistants, “a stable of Arabian horses, and bulldozers.”113

The Turki-bin Laden connection, which was cemented by Turki’s chief of staff and bin Laden’s teacher Ahmed Badeeb, may have been renewed as late as 1998:

In sworn statements after 9/11, former Taliban intelligence chief Mohammed Khaksar said that in 1998 the prince sealed a deal under which bin Laden undertook not to attack Saudi targets. In return, Saudi Arabia would provide funds and material assistance to the Taliban…. Saudi businesses, meanwhile, would ensure that money also flowed directly to bin Laden. Turki would deny after 0/11 that any such deal was done with bin Laden. One account has it, however, that he himself met with bin Laden – his old protégé from the days of the anti-Soviet jihad – during the exchanges that led to the deal.114

Bin Laden’s move to the Sudan in 1991-92, the move organized by Ali Mohamed, appears to have been done in collaboration with his family. There is hotly contested evidence that Osama participated with his brothers in the construction of the Port Sudan airport, a project underwritten with funds from the Saudi royal family.115 According to Lawrence Wright, “the Saudi Bnladen Group got the contract to build an airport in Port Sudan, which brought Osama frequently into the country to oversee the construction. He finally moved to Khartoum in 1992….”116

Not contested, but largely overlooked, is the evidence of how bin Laden financed his move, through investing $50 million in the Sudanese al-Shama Islamic bank – a bank that also had support from both the bin Laden family and the Saudi royal family. As the Chicago Tribune reported in November 2001,

According to a 1996 State Department report on bin Laden’s finances, bin Laden co-founded the Al Shamal bank with a group of wealthy Sudanese and capitalized it with $50 million of his inherited fortune…..117

According to public records, among the investors in the Al Shamal Islamic Bank is a Geneva-based financial services conglomerate headed by Prince Mohamed al-Faisal al-Saud, [brother of Prince Turki], son of the late King [Faisal al-]Saud and a cousin [i.e. nephew] of the current Saudi monarch, King Fahd.

The Al Shamal bank, which opened for business in 1990, admits that Osama bin Laden held three accounts there between 1992 and 1997, when he used Sudan as his base of operations before fleeing to Afghanistan. But the bank insists in a written statement that bin Laden “was never a founder or a shareholder of Al Shamal Islamic Bank.”

Told of the bank’s statement, the State Department official replied that “we stand by” the assertion that bin Laden put $50 million into the bank.

The Al Shamal bank does acknowledge that among its five “main founders” and principal shareholders is another Khartoum bank, the Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan. According to public records, 19 percent of the Faisal Islamic Bank is owned by the Dar Al-Maal Al-Islami Trust, headed by Saudi Prince [Mohammed al-Faisal] al-Saud.

|

Faisal Islamic Bank of Sudan |

(The Dar Al-Mal Al-Islami or DMI Trust, “based in the Bahamas and with its operations center in Geneva,” was one of a spate of banks, mostly dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, that were set up with western guidance and assistance – in DMI’s case the assistance came from Price Waterhouse and eventually Harvard University.118 DMI was one of the two main banks which, according to Jane’s Intelligence Review, had been funding the Makhtab and also the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), of which more below.)119

The $3.5 billion DMI Trust, whose slogan is “Allah is the purveyor of success,” was founded 20 years ago to foster the spread of Islamic banking across the Muslim world. Its 12-member board of directors includes Haydar Mohamed Binladen, according to a DMI spokesman, a half-brother of Osama bin Laden…..

Though small, the Al Shamal Islamic Bank enabled bin Laden to move money quickly from one country to another through its correspondent relationships with some of the world’s major banks, several of which have been suspended since Sept. 11.

The Al Shamal bank was identified as one of bin Laden’s principal financial entities during the trial earlier this year of four Al Qaeda operatives convicted in the 1998 bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa.120

One might have expected this early and revealing insight into bin Laden’s finances to have been developed in the spate of privileged bin Laden and al Qaeda books that appeared in the years after 2001. In fact I have located only one brief inconsequential reference, in Steve Coll’s The Bin Ladens: “Osama had reorganized his personal banking at the Al-Shamal Bank in Khartoum, but his accounts gradually dried up.”121

There is of course no mention of the al-Shamal Bank in the 9/11 Commission Report.

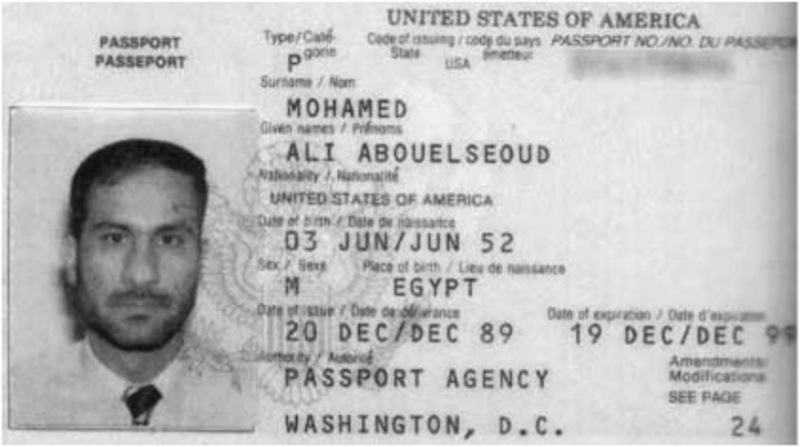

Federal Protection for Osama bin Laden’s Brother-in-Law, Mohammed Jamal Khalifa

It seems clear that the 1980s official USG block against antiterrorism actions that might embarrass the Saudis was still in force in America in 1995. We see this in the extraordinary federal protection extended to Mohamed Jamal Khalifa, Osama bin Laden’s best friend and brother-in-law.

|

Mohammed Jamal Khalifa |

On December 16, 1994, the San Francisco FBI arrested Khalifa in Morgan Hills (not far from Ali Mohamed’s home). Khalifa’s business card had been discovered in a search one year earlier of Sheikh Rahman’s residence, after which he had been named as an unindicted co-conspirator in the Landmarks case. Soon afterwards, a State Department cable described him as

a known financier of terrorist operations and an officer of an Islamic NGO in the Philippines that is a known Hamas front. He is under indictment in Jordan in connection with a series of cinema bombings earlier this year.122

Khalifa, in other words, was like Ali Mohamed involved in terrorist operations on an international level. He was an important source of information and talked freely to the FBI agents who arrested him. In his possession they found “documents that connected Islamic terrorist manuals to the International Islamic Relief Organization, the group that he had headed in the Philippines.”123 And in his notebook they found evidence linking him directly to Ramzi Yousef, who at the time was the FBI’s most-wanted terrorist for his role in the 1993 WTC bombing.

But as Peter Lance narrates, “The Feds never got a chance to question him.” Instead, in January 1995, a decision was made by Secretary of State Warren Christopher and supported by Deputy Attorney General Jamie Gorelick to whisk Khalifa from the United States to Jordan for trial, where he was soon “acquitted of terrorism charges and allowed to move to Saudi Arabia.”124

“I remember people at CIA who were ripshit at the time” over the decision, says Jacob L. Boesen, an Energy Department analyst then working at the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center. “Not even speaking in retrospect, but contemporaneous with what the intelligence community knew about bin Laden, Khalifa’s deportation was unreal.”125

Even more unreal was the decision of a court in a civil case to return to Khalifa before his deportation the contents of his luggage, including his notebook and other computer files.126

I believe that Peter Lance, after all his meticulous scholarship, failed to identify who was really being protected by this evasive measure. He writes that Khalifa, from 1983 to 1991, “had been trusted by al Qaeda with running the Philippines branch of the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), one of their key NGOs.”127

But the IIRO was in the hands of a far greater power than al Qaeda, which in any case did not exist in 1983. It was a charitable organization that had been authorized in 1979 by Saudi royal decree, as an affiliate of another key institution of the royal family, the Muslim World League (MWL).128 According to former CIA officer Robert Baer, the IIRO has been run “with an iron hand” by Prince Salman ibn Abdul-Aziz al Saud (the brother of Saudi King Abdullah), who “personally approved all important appointments and spending.”129

The creation date of 1979 reflects the important shift in that year of the Saudi royal family’s attitude towards the political Islamism of the Muslim Brotherhood or Ikhwan (of which Mohammed Jamal Khalifa was a senior member). As already noted, 1979 was the year radical Wahhabis, seized the Grand Mosque at Mecca. In response, the Saudi family foundations like the IIRO, moved to subsidize the emigration of the Muslim Brotherhood.130

Thus Khalifa’s status in the IIRO was not anomalous. Besides the bombings in Jordan, the IIRO has also been linked to support of terrorists in the Philippines,131 India,132 Indonesia,133 Canada,134 Albania, Chechnya, Kenya,135 and other countries, notably Bosnia.136 In particular Khalifa personally has been accused of financing the Philippine terrorist group Abu Sayyaf (which in 1993 had kidnapped an American Bible translator).137 Yet “The U.S. government has not designated Khalifa as a financial supporter of terrorism.”138

Federal Protection for Al-Qaeda Plotter Khalid Sheikh Mohammed

The Saudi royal protection for Jamal Khalifa was more than matched by the Qatari royal protection of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), Ramzi Yousuf’s uncle and co-conspirator in the Philippines. The 9/11 Commission, who judged KSM to be “the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks,” made a muted acknowledgment of this Qatari protection of him:

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — Yousef’s uncle, then located in Qatar — was a fellow plotter of Yousef’s in the Manila air plot and had also wired him some money prior to the Trade Center bombing. The U.S. Attorney obtained an indictment against KSM in January 1996, but an official in the government of Qatar probably warned him about it. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed evaded capture (and stayed at large to play a central part in the 9/11 attacks).139

From other sources, notably Robert Baer who was then a CIA officer in Qatar, we learn that the “official” was Sheikh Abdallah bin Khalid bin Hamad al-Thani, the Qatari minister of the Interior and the brother of then Qatari Emir Sheik Hamad bin Khalid al-Thani.140 According to ABC News,

Mohammed is believed to have fled Qatar with a passport provided by that country’s government. He is also believed to have been given a home in Qatar as well as a job at the Department of Public Water Works. Officials also said bin Laden himself visited Abdallah bin Khalid al-Thani in Qatar between the years of 1996 and 2000.141

In Triple Cross, Peter Lance, who does not mention KSM’s escape from Qatar, focuses instead on the way that, later in the same year, federal prosecutors kept his name out of the trial of Ramzi Yousuf in connection with the 1993 World Trade Center bombing:

Assistant U.S. Attorneys Mike Garcia and Dietrich Snell presented a riveting, evidence case… and characterized the material retrieved from Ramzi’s Toshiba laptop as ‘the most devastating evidence of all.”…. While Yousuf’s Toshiba laptop… contained the full details of the plot later executed on 9/11, not a word of that scenario was mentioned during trial. …. Most surprising, during the entire summer-long trial, the name of the fourth Bojinka conspirator, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed…was mentioned by name only once, in reference to a letter found in [Yousuf’s apartment].142

Lance repeatedly suggests that U.S. prosecutors in New York, and particularly Dietrich Snell, were responsible for minimizing the role of Khalid Sheikh Mohamed and other shortcomings, because they were seeking “to hide the full truth behind the Justice Department’s failures.”143 But the matter of KSM’s escape in 1996, like the release of Jamal Khalifa, was sensitive at a much higher level than that of prosecutors. It was a matter that reached back into the black hole that is represented by the ultimate United States dependency on Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and OPEC, for the defense of the petrodollar.

In other words, the suppression of KSM’s name was not surprising at all. On the contrary, it was totally consistent with one of the most sensitive and controversial features of the 9/11 story: the much-discussed fact that before CIA two counterterrorist officers protected two of the alleged hijackers from detection and surveillance by the FBI.

Federal Protection for Alleged 9/11 Hijackers

Morgenthau’s hypothesis that the CIA was protecting Saudi criminal assets received further corroboration in the wake of 9/11. There is now evidence, much of it systematically suppressed by the 9/11 Commission, that before 9/11 CIA officers Richard Blee and Tom Wilshire inside the CIA’s Bin Laden Unit, along with FBI agents Dina Corsi et al., were protecting from investigation and arrest two of the eventual alleged hijackers on 9/11, Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi — much as the FBI had protected Ali Mohamed from arrest in 1993.

There are also indications that al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi, like Hampton-El before them, may have been receiving funds indirectly from the Saudi Embassy in Washington:

“[B]etween 1998 and 2002, up to US $73,000 in cashier cheques was funneled by [Saudi Ambassador Prince] Bandar’s wife Haifa – who once described the elder Bushes as like “my mother and father” – to two Californian families known to have bankrolled al-Midhar and al-Hazmi. … Princess Haifa sent regular monthly payments of between $2,000 and $3,500 to Majeda Dweikat, wife of Osama Basnan, believed by various investigators to be a spy for the Saudi government. Many of the cheques were signed over to Manal Bajadr, wife of Omar al-Bayoumi, himself suspected of covertly working for the kingdom. The Basnans, the al-Bayoumis and the two 9/11 hijackers once shared the same apartment block in San Diego. It was al-Bayoumi who greeted the killers when they first arrived in America, and provided them, among other assistance, with an apartment and social security cards. He even helped the men enroll at flight schools in Florida.”144

The Report of the Joint Congressional Inquiry into 9/11 (173-77), though very heavily redacted at this point, supplies corroborating information, including a report that Basnan had once hosted a party for the “Blind Sheikh” Omar Abdel Rahman. In other words, the Congressional investigation found indications that the same protection extended to those protected in the crimes of 1993, were protected again in 9/11.

The 9/11 Commission Report recognized that there had been an intelligence failure with respect to al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi, but treated it as an accident that might not have occurred “if more resources had been applied.”145 This explanation, however, has since been rejected by 9/11 Commission Chairman Tom Kean. Asked if the failure to deal appropriately with al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi could have been a simple mistake, Kean replied:

Oh, it wasn’t careless oversight. It was purposeful. No question about that.…The conclusion that we came to was that in the DNA of these organizations was secrecy. And secrecy to the point of ya don’t share it with anybody.146

In 2011 an important book by Kevin Fenton, Disconnecting the Dots, demonstrated conclusively that the withholding was purposive, and sustained over a period of eighteen months.147 This interference and manipulation became particularly blatant and controversial in the days before 9/11; it led one FBI agent, Steve Bongardt, to predict accurately on August 29, less than two weeks before 9/11, that “someday someone will die.”148

Before reading Fenton’s book, I was satisfied with Lawrence Wright’s speculations that the CIA may have wanted to recruit the two Saudis; and that “The CIA may also have been protecting an overseas operation [possibly in conjunction with Saudi Arabia] and was afraid that the F.B.I. would expose it.”149 However I am now persuaded that Lawrence Wright’s explanation, that the CIA was protecting a covert operation, may explain the beginnings of the withholding in January 2000, but cannot explain its renewal in the days just before 9/11.

Fenton analyzes a list of thirty-five different occasions where the two alleged hijackers were protected in this fashion, from January 2000 to about September 5, 2001, less than a week before the hijackings.150 In his analysis, the incidents fall into two main groups. In the earlier incidents he sees an intention “to cover a CIA operation that was already in progress.”151 However, after “the system was blinking red” in the summer of 2001, and the CIA expected an imminent attack, Fenton can see no other explanation than that “the purpose of withholding the information had become to allow the attacks to go forward.”152

In support of Fenton’s conclusion, there is evidence (not mentioned by him) indicating that in mid-2001 the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center (CTC), who were the chief suppliers of the CIA protection, believed an al-Qaeda attack was imminent, and that al-Mihdhar was important to it. On August 15, CIA Counterterrorism Chief Cofer Black told a secret Pentagon conference, “We’re going to be struck soon…. Many Americans are going to die, and it could be in the U.S.”153 Three weeks earlier, CTC Deputy Chief Tom Wilshire had written that ““When the next big op is carried out… Khallad [bin Attash] will be at or near the top ….Khalid Midhar should be very high interest.”154 Yet Wilshire (like his superior, Richard Blee), instead of expediting to the FBI the transmission of his knowledge about al-Mihdhar, did the opposite: he

not only failed to tell anyone else involved in the hunt [for Al-Mihdhar] that Almihdhar would likely soon be a participant in a major al-Qaeda attack inside the US, but also supported a dubious procedure which meant that the FBI was only able to focus a fraction of the resources it had on the hunt.155

Fenton’s serious allegation has to be considered in the light of the earlier instances of protection we have surveyed:

1) the protection given to Salameh and Abouhalima in the 1990 Kahane murder, leaving them free to participate in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing;

2) the failure for two or three years to process Ali Mohamed’s documents seized in 1990, which could have prevented the 1993 World Trade Center bombing;

3) the release of Ali Mohamed from RCMP detention in 1993, leaving him free to participate in the 1998 Nairobi Embassy bombing;