In April 2011, U.S. veterans spoke out for the first time about sicknesses related to Agent Orange exposure on Okinawa during the Vietnam War era (here). Since then, dozens of retired service members have alleged that toxic herbicides were stored and sprayed on the island (here) – as well as buried in large volumes on Futenma Air Station (here) and, what is now, a popular tourist area in Chatan Town (here). Japanese former base workers have corroborated veterans’ accounts and photographs seem to show barrels of these herbicides on Okinawa. U.S. military documents cite the presence of Agent Orange there during the 1960s and ‘70s (here and there).

Suggestions that these poisonous substances were widely used on their island have worried Okinawa residents. Stories about the usage of Agent Orange have repeatedly made the front page of Okinawa Times and Ryukyu Shimpo as well as becoming the basis of four TV documentaries – including the award-winning Defoliated Island (an English version of which is viewable here).

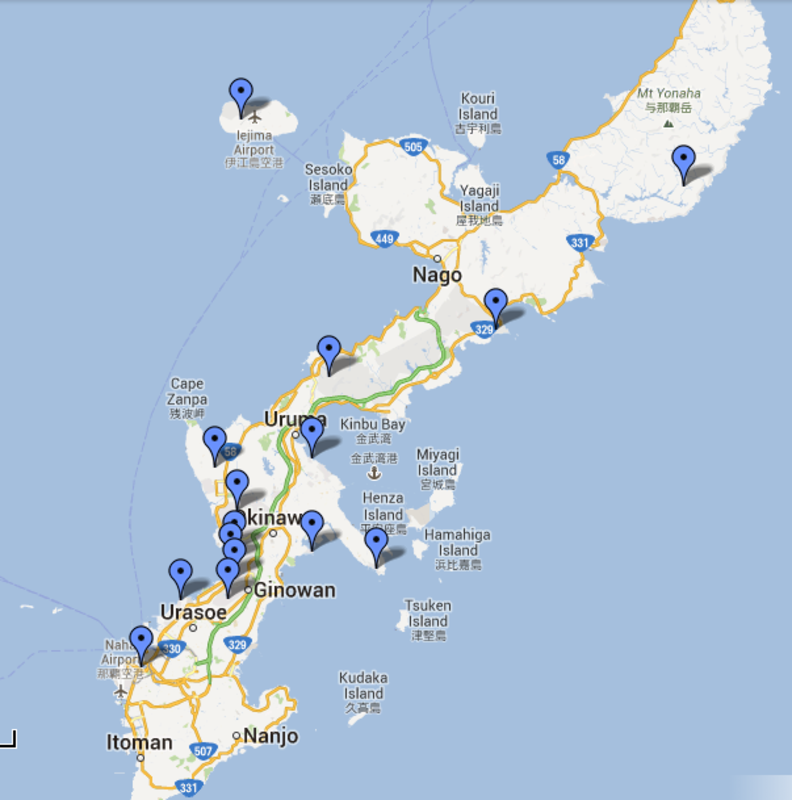

Map of Alleged Locations of Agent Orange on Okinawa (link) |

Alleged Locations of Agent Orange on Okinawa

During the past two years, local politicians, including Governor Hirokazu Nakaima, have demanded that the U.S. government come clean on the issue.

Earlier this year, the Pentagon revealed that it had concluded its own 9-month investigation into allegations reported by The Japan Times and other newspapers. On February 19, the results of this investigation were announced at a meeting attended by representatives from the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs and diplomats from the Embassy of Japan.

Authored by retired Air Force colonel Alvin Young, the investigation boiled down the allegations into seven points – then dismissed them one by one.

| Alvin Young collection on Agent Orange, National Agricultural Library

Navigating the Collection <–1 Finding Aid <-3-> Introduction, Biographical Sketch, Scope and Content, Series Description, Container List |

In response to veterans’ claims that ships had transported Agent Orange via the island on the way to the Vietnam War, the investigation stated that such vessels were not designed for the delivery of barrels – nor were there any shipping records that supported veterans’ allegations. The investigation also cited documents – long-believed destroyed – which it claimed supported its assertion that Agent Orange had been delivered directly from the U.S. to Vietnam without passing through Okinawa.

Another issue addressed by the investigation was a 2003 U.S. Army report – titled “An Ecological Assessment of Johnston Atoll” – which stated that 25,000 barrels of Agent Orange had been on Okinawa prior to 1972. The investigation dismissed this by arguing that its authors “were not DoD [Department of Defense] employees, nor were they likely familiar with the issues surrounding Herbicide Orange.” The Pentagon further distanced itself from the 25,000 barrel statement; it claimed it was “inaccurate and does not reflect the facts as known to the Army or to the U.S. Government.”

A second U.S. Army report that cited the presence of a herbicide stockpile in Kadena in 1971 was also repudiated by the investigation – this time on the basis that a follow-up report, prepared three years later in 1974, “did not identify any stockpiles of Herbicide Orange… in Okinawa.”

In conclusion, the investigation stated:

“[A]fter an extensive search of all known and available records, there were no documents found that validated the allegations that Herbicide Orange was involved in any of these events [the burials at Chatan and Futenma], nor were there records to validate that Herbicide Orange was shipped to or through, unloaded, used or buried on Okinawa.”

Following the release of the full 29-page text (available here) of the investigation in March, scientists, veterans and environmental groups disputed the veracity of its contents.

Former U.S. stevedores stationed on Okinawa questioned how the Pentagon had been able to come up with shipping records for Agent Orange when they’d been told such documents had been destroyed long ago. Other veterans argued that the Pentagon’s disowning of the 2003 Army report that cited 25,000 barrels on the island was disingenuous – had it not been thoroughly screened by the Department of Defense in the first place, its publication would never have been permitted. The same veterans also suggested that the reason why the later report failed to mention the Agent Orange stockpile at Kadena was because it had been removed from the island in 1972 – the same year the U.S. shipped its herbicide stockpiles from around the world to Johnston Island in the northern Pacific for eventual destruction in 1977.

As well as highlighting the apparent discrepancies in the investigation, many critics also questioned the Pentagon’s choice of author, Alvin Young. They cited his previous funding from the manufacturers of Agent Orange – Monsanto and the Dow Chemical Company – and his close ties to the Department of Defense. Mark Wright, a spokesman for the Pentagon, defended Young by stating he is “a world recognized and published authority on the topic [of Agent Orange].”

However, of most concern to experts and veterans was what the investigation failed to do. No bases on Okinawa where Agent Orange had allegedly been stored were visited. The photographic evidence was not addressed and, perhaps most tellingly, none of the eye witnesses making these claims were interviewed.

“It’s like saying that if there wasn’t a paper trail, then it didn’t happen. The report clearly wanted to emphasize that there was nothing in the files they looked at, but that’s only one type of evidence,” said Richard Clapp, Professor Emeritus at Boston University School of Public Health.

Richard Clapp |

Singled out for particular criticism by Clapp, who has 30 years experience researching Agent Orange, was the investigation’s failure to interview any of the U.S. veterans claiming exposure. In July 2012, for example, ten former service members wrote a letter to the U.S. Senate volunteering testimony on the issue but none of them was contacted for the Pentagon investigation.

Kris Roberts, the former maintenance chief of Futenma Air Station who claimed to have unearthed barrels of Agent Orange on the installation in 1981, thinks he knows the reason why he wasn’t interviewed.

“Being a retired Lieutenant Colonel with five medals for superior performance gives me a high degree of creditability. There is no doubt in my mind that they decided in advance not to contact me – but there is no excuse whatsoever for this,” said Roberts, currently a state representative of New Hampshire.

Mark Wright stated the Pentagon had not interviewed any veterans because it had wanted to make “best use of government resources”. He also appeared keen to emphasize that the Pentagon was not accusing the dozens of veterans of fabricating their accounts. They “remembered actual events that happened… However, the source documents showed that, while these events took place, either the material involved was not Herbicide Orange or the location was not Okinawa.”

Herbicide expert Clapp also criticized the investigation’s failure to conduct soil checks. “One of the obvious ways to resolve conflicting – or missing – evidence is to test environmental samples taken now from sites where burial was alleged to have happened. Ideally this should be done by an independent contractor familiar with environmental and wildlife reservoirs of Agent Orange and its dioxin contaminants.”

Although dioxin, the poison found in Agent Orange, is quickly broken down by sunlight, it can remain toxic for decades when buried beneath the ground. On former U.S. military storage areas in Vietnam, for example, the soil still remains polluted more than 40 years later and local residents exhibit high levels of contamination and its associated health problems.

Despite a 1973 Japan-US Joint Committee agreement which allows local leaders to request environmental tests on bases located in their communities, the U.S. military and the Japanese government in Japan has refused to permit them. For example, in September 2011, demands from Nago City Council for dioxin tests on the Marine Corps Camp Schwab – a base believed to have been a storage area for Agent Orange – were turned down (see here)

The investigation’s failure to address potential contamination dismayed Kawamura Masami, director of Environmental Policy and Justice at Citizens’ Network for Biodiversity in Okinawa – the NGO demanding a full inquest into Agent Orange usage on the island.

“Even though the investigation was submitted on an intergovernmental level between Japan and the U.S., it was substandard. Washington wanted to bring closure to the issue of Agent Orange on Okinawa – but what it really showed was that the U.S. government looks down on the government of Japan. It didn’t think that the Japanese government would analyze the report in any detail.”

Indeed, Tokyo has made no comment on the investigation, nor has it publicly questioned its findings. But it might soon regret such acquiescence. In April, it was announced that over the coming years, some of the U.S. bases at the centre of Agent Orange allegations would be returned to civilian control. These installations include Futenma Air Station and Makiminato Service Area in Urasoe City, where veterans claim the military maintained its primary stockpile of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War.

If the Pentagon conducted environmental tests on these installations and the results revealed Agent Orange dioxins, U.S. service members currently stationed there would undoubtedly demand remediation. Washington is particularly sensitive to pollution worries among its own troops in the wake of recent revelations regarding drinking water contamination at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina which exposed as many as 750,000 service members and their families to harmful substances. In 2012, Congress was forced to pass an act in an attempt to resolve the problem.

However if the Pentagon can delay environmental tests on its Okinawa bases until the land reverts to civilian control – currently scheduled to occur after 2022 – it will be able to shift the cost of clean-up onto the shoulders of Japanese tax-payers. Under the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), Washington is absolved from all responsibility to restore military land formerly under its control to safe environmental levels.

So how much would such remediation cost?

In April, a meeting in Naha City pegged the price of cleaning former military land at 60 billion yen – approximately $600 million (a Japanese TV news report of this meeting can be seen here). However these estimates were only based upon the presence of pollutants such as mercury and lead. Factoring Agent Orange’s dioxin into calculations, the costs could skyrocket to a price tag potentially approaching $1 billion.

Given these figures – in addition to the compensation for which exposed veterans would be liable – the Pentagon’s need to maintain its denials is perhaps understandable. Herb Worthington, head of the Agent Orange and Other Toxic Substances Committee of the Vietnam Veterans of America, is only too familiar with such a stance. His organization led the campaign to secure assistance for U.S. veterans exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam – a struggle which finally convinced Washington to compensate sick service members starting in 1991.

“Eventually, I am sure that Okinawa will be proven to have used or stored Agent Orange. But by the time it is admitted, most of the outspoken Veterans will have passed away. The mantra of our government agencies is ‘Deny, deny, deny.’”

* * *

Locations where the Pentagon admits the usage of Agent Orange: Cambodia, Canada, Korea, Laos, Puerto Rico, Thailand, U.S.A. and Vietnam.

Places where U.S. veterans and local residents claim Agent Orange usage – but the Pentagon denies allegations: Guam, Johnston Island, mainland Japan, Okinawa, Panama, Philippines and Saipan.

* * *

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The Japan Times on June 4, 2013.

Reccommended citation: Jon Mitchell, “‘Deny, deny until all the veterans die’: Pentagon investigation into Agent Orange on Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 23, No. 2. June 10, 2013.

Related articles

• Jon Mitchell, “Herbicide Stockpile” at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa: 1971 U.S. Army report on Agent Orange

• Jon Mitchell, Were U.S. Marines Used as Guinea Pigs on Okinawa?

• Jon Mitchell, Agent Orange on Okinawa – The Smoking Gun: U.S. army report, photographs show 25,000 barrels on island in early ‘70s

• Jon Mitchell, Seconds Away From Midnight”: U.S. Nuclear Missile Pioneers on Okinawa Break Fifty Year Silence on a Hidden Nuclear Crisis of 1962

• Jon Mitchell, Agent Orange at Okinawa’s Futenma Base in 1980s

• Jon Mitchell, U.S. Veteran Exposes Pentagon’s Denials of Agent Orange Use on Okinawa

• Jon Mitchell, U.S. Vets Win Payouts Over Agent Orange Use on Okinawa

• Jon Mitchell, Agent Orange on Okinawa: Buried Evidence?

• Fred Wilcox, Dead Forests, Dying People: Agent Orange & Chemical Warfare in Vietnam

• Jon Mitchell, Agent Orange on Okinawa – New Evidence

• Jon Mitchell, US Military Defoliants on Okinawa: Agent Orange

• Roger Pulvers and John Junkerman, Remembering Victims of Agent Orange in the Shadow of 9/11

• Ikhwan Kim, Confronting Agent Orange in South Korea

• Ngoc Nguyen and Aaron Glantz, Vietnamese Agent Orange Victims Sue Dow and Monsanto in US Court