“You lose, you lose, you lose, you lose, and then you win.”

Rosa Luxemburg

|

The worldwide revolutionary movement inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 encompassed a powerful cultural component: hundreds of thousands of literary, visual, and performing artists – writers, painters, filmmakers, photographers, composers, and others – passionately devoted their work to the monumental task of a radical reconstitution of the world. As a prominent Yugoslav author, Miroslav Krleža, was to write in 1924: “Lenin’s name in the year 1917 signified a lighthouse beacon above the shipwreck of international civilization.”

Not only was capitalism widely identified with a devastatingly bellicose form of imperialism epitomized by World War I, but also the notion that capitalism is genuinely compatible with freedom struck many contemporary observers as preposterous:

The worker under capitalism is a “free” woman. She is free to go where she likes. She does not have to work for any one boss. If she does not like an employer she can quit, but if she does not like the employing class she cannot quit, unless she is prepared to starve. She is a slave to a class. Her freedom amounts to having a longer chain than her predecessors – the serf or chattel slave. It is true that she is not bought and sold and that she has liberties unknown to former generations of workers. It is also true that she takes greater risks than former workers and that while she is not sold she is obliged to sell herself.

Yet how could it be otherwise so long as the ownership and control of life’s productive resources remained in the hands of a super-wealthy minority at the expense of everyone else? Convinced that the dominant socioeconomic system was incorrigibly exploitative and oppressive – as well as warlike and destructive – dissident writers and other radical artists of the early twentieth century dedicated themselves to portraying the lives and struggles of those who suffered its depredations and sought a way out from its nightmarish cul-de-sac. As the abolitionist artists of the nineteenth century fought against chattel slavery and serfdom, so their neo-abolitionist successors fought on against wage slavery, confident that in the not too distant future a worldwide revolution would open the way to a cooperative commonwealth where emancipated humanity could at long last begin to live up to its fullest potential.

Though a roster of writers committed to profound social transformation would be virtually endless, it might be helpful to list at random a handful of representative names, some more familiar than others: Lu Xun, Maxim Gorky, Bertolt Brecht, Alexandra Kollontai, Jaroslav Hašek, Premchand, Yi Ki-yong, César Vallejo, Vladimir Mayakovsky, José Mancisidor, Patrícia Galvão, Halldór Laxness, Meridel Le Sueur, Victor Serge, Nâzım Hikmet, Pablo Neruda, Mao Dun, Theodore Dreiser, Mulk Raj Anand, Langston Hughes, Marcel Martinet, Sata Ineko, Hirabayashi Taiko, Moa Martinson, Harry Martinson, Ivar Lo-Johansson…

|

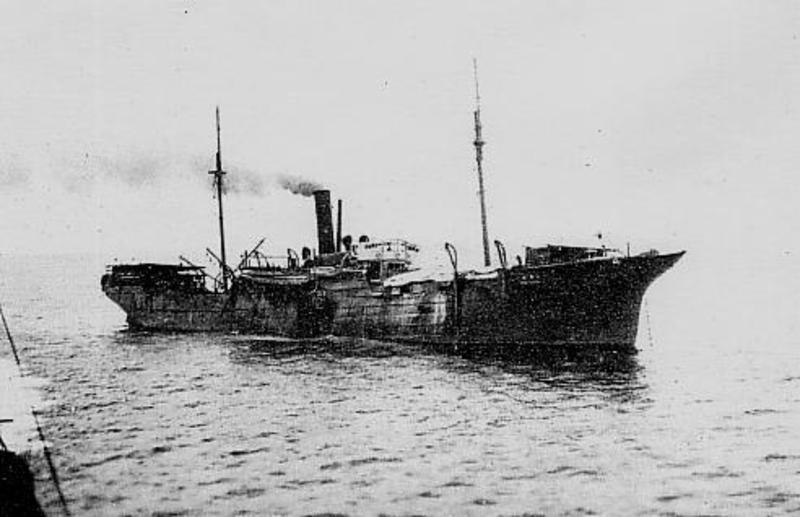

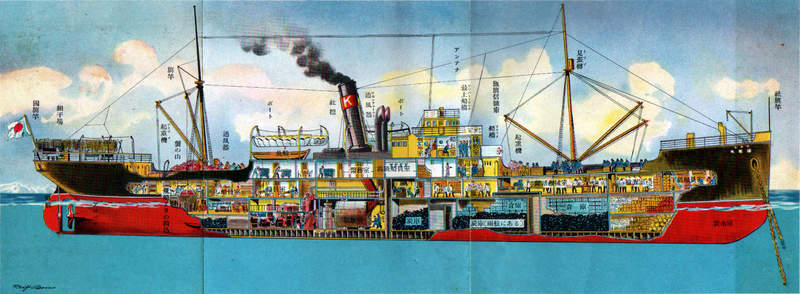

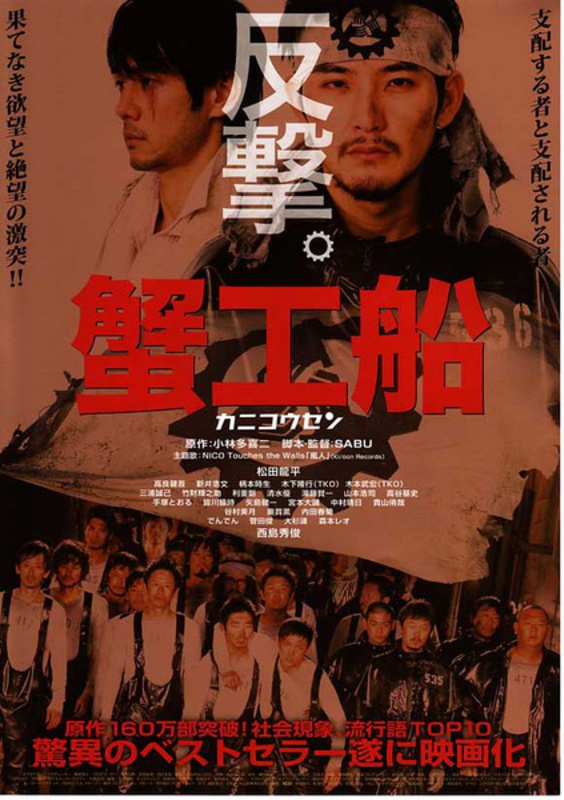

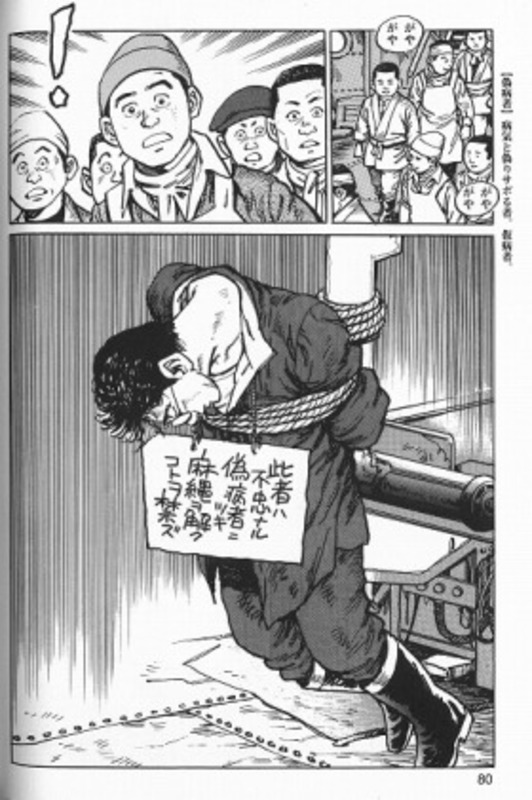

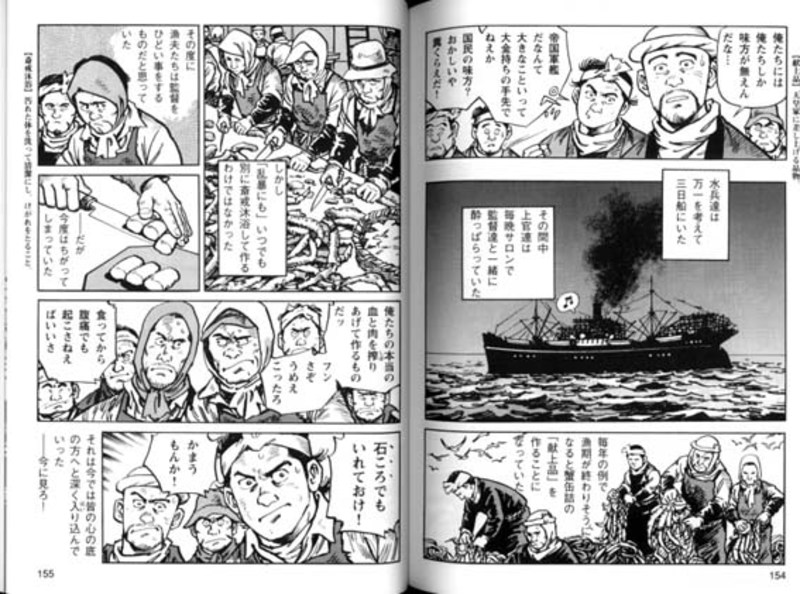

One of Japan’s most renowned revolutionary authors was Kobayashi Takiji (小林 多喜二, 1903-1933), a prolific young communist writer best known for his 1929 short novel The Crab Cannery Ship (Kani kosen, 蟹工船). Based on an actual incident that took place in 1926, the novel follows a motley crew of unorganized, mostly low-skilled laborers who are subjected to such savage working conditions onboard a crab cannery ship that they almost spontaneously start to organize and unite in order to fight back and survive. Takiji’s fast-paced and vivid novel succeeds in constructing an extraordinarily potent metaphor for capitalism itself – a system whose sole preoccupation lies in the accumulation of profit, and which is fundamentally indifferent to human life, liberty, and happiness. The novel has been translated into numerous languages, including Russian, Chinese, English, Korean, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, German, French, Polish, and Norwegian. A classic of Japanese proletarian literature, The Crab Cannery Ship experienced an enormous revival of popularity in 2008 and early 2009, selling hundreds of thousands of copies in an economically depressed Japan. As Tokyo University professor Komori Yoichi comments in his introduction to its most recent English translation, “Kobayashi Takiji’s theory of collective action continues to be valid in the twenty-first century.”

|

|

|

|

Much of the early-twentieth-century revolutionary optimism and some of the proletarian artists themselves were to vanish amid the turmoil of repression and war. Takiji himself was tortured and killed by police in Tokyo at age 29. Many other radical artists have been almost forgotten along with much or most of their work. This is more than a pity, for the current global status quo is in some ways even more pernicious than it was in their days. Nowadays, to note only one example, the insidious idea of “marketing” and “selling” oneself seems to all too many nothing more than commonsensical.

Given the possibly catastrophic course our globe appears to be following, it might be high time for a worldwide resurgence – on a tremendous scale – of proletarian literature, and of all the proletarian arts. For in conjunction with internationalist grassroots solidarity, radical art could just possess the power to transform the world for the incomparably better.

|

What follows is a baker’s dozen of short scenes and passages that convey the dynamic and flavor of The Crab Cannery Ship:

Off to hell!

“Buddy, we’re off to hell!”

Leaning over the deck railing, two fishermen looked out on the town of Hakodate stretched like a snail embracing the sea. One of them spit out a cigarette he had smoked down to his fingertips. The stub fell skimming the tall side of the ship, turning playfully every which way. The man stank of liquor.

Steamships with red bulging bellies rose from the water; others being loaded with cargo leaned hard to one side as if tugged down by the sea. There were thick yellow smokestacks, large bell-like buoys, launches scurrying like bedbugs among ships. Bleak whirls of oil soot, scraps of bread, and rotten fruit floated on the waves as if forming some special fabric. Blown by the wind, smoke drifted over waves wafting a stifling smell of coal. From time to time a harsh rattle of winches traveling along the waves reverberated against the flesh.

Directly in front of the crab cannery ship Hakkomaru rested a sailing ship with peeling paint, its anchor chain lowered from a hole in its bow that looked like an ox’s nostril. Two foreign sailors with pipes in mouth paced the deck back and forth like automatons. The ship seemed to be Russian. No doubt it was a patrol vessel sent to keep an eye on the Japanese cannery ship.

|

Poverty

The two fishermen, peering down through the hatch into workers’ quarters in the dim bottom of the ship, saw a noisy commotion inside the stacked bunks, like a nest full of birds’ darting faces. The workers were all boys of fourteen or fifteen.

“Where you from?”

“X District.”

They were all children from Hakodate’s slums. Poverty had brought them together.

“What about the guys in the bunks over there?”

“They’re from Nambu.”

“And those?”

“Akita.” Each cluster of bunks belonged to a different region.

“Where in Akita?”

“North Akita.” The boy’s nose was running with thick, oozing mucus, and the rims of his eyes were inflamed and drooping.

“You farmers?”

“Yeah.”

The air was stifling, filled with the sour stench of rotten fruit. Dozens of barrels of pickled vegetables were stored next door, adding their own shit-like odor.

Them or us

“I’d like to say a word,” declared the manager. He had the powerful build of a construction worker. Placing one foot on a partition between bunks, he maneuvered a toothpick inside his mouth, at times briskly ejecting bits of food stuck between his teeth.

“Needless to say, as some of you may know, this crab cannery ship’s business is not just to make lots of money for the corporation but is actually a matter of the greatest international importance. This is a one-on-one fight between us, citizens of a great empire, and the Russkies, a battle to find out which one of us is greater – them or us. Now just supposing you lose – this could never happen, but if it did – all Japanese men and boys who’ve got any balls at all would slit their bellies and jump into the sea off Kamchatka. You may be small in size but that doesn’t mean you’ll let those stupid Russkies beat you.

“Another thing, our fishing industry off Kamchatka is not just about canning crabs and salmon and trout, but internationally speaking it’s also about keeping up the superior status of our nation, which no other country can match. And moreover, we’re accomplishing an important mission in regard to our domestic problems like overpopulation and shortage of food. You probably have no idea what I’m talking about, but anyhow I’ll have you know that we’ll be risking our lives cutting through those rough northern waves to carry out a great mission for the Japanese empire. And that’s why our imperial warship will accompany us and protect us all along the way…. Anyone who acts up trying to ape this recent Russky craze, anyone who incites others to commit outrageous acts, is nothing but a traitor to the Japanese empire. And though something like that could never happen, make damned sure that what I’m saying gets through to your heads…”

The manager sneezed repeatedly as he began sobering up.

Won’t matter a damn

As the ship reached the Sea of Okhotsk, the color of the water became a clearer gray. The chilling cold penetrated the laborers’ clothing and turned their lips blue as they worked. The colder it became, the more furiously a fine snow, dry as salt, blew whistling against them. Like tiny shards of glass, the snow pierced faces and hands of the laborers and fishermen who worked on all fours on the deck. After each wave washed over them the water promptly froze, making the deck treacherously slippery. The men had to stretch ropes from deck to deck, and work dangling from them like diapers hung out on the clothesline. The manager, armed with a club for killing salmon, was roaring like mad.

Another crab cannery ship that had sailed out of Hakodate at the same time had gotten separated from them. Even so, whenever their ship surged to the summit of a mountainous wave, two masts could be seen swaying back and forth in the distance like the waving arms of a drowning person. Wisps of smoke torn by the wind flew by skimming the waves. Intermittent howls of the other ship’s whistle were clearly audible amid the waves and shouts. Yet the next instant the one ship rose high and the other fell away into the depths of a watery crevasse.

The crab cannery ship carried eight fishing boats. The sailors and fishermen were forced to risk their lives tying down the boats so that the waves, baring their white teeth like thousands of sharks, would not tear them off. “Losing one or two of you won’t matter a damn, but if a boat gets lost it can’t get replaced,” shouted the manager distinctly.

|

Total impunity

Crab cannery ships were all old and battered. It didn’t matter a damn to executives in some building in Tokyo’s financial district that workers were dying in the northern Sea of Okhotsk. Once capitalism’s quest for profits in its usual places comes to a deadlock, then interest rates drop, excess money piles up, and capital will literally do anything and go anywhere in a frenzied search for a way out. Given those circumstances it was no wonder that capital’s profit-seekers fell in love with the crab cannery ships, each one able to bring in countless hundreds of thousands of yen.

Crab cannery ships were considered factories, not ships. Therefore maritime law did not apply to them. Ships that had been tied up for twenty years and were good for nothing but scrap iron, vessels as battered as tottering syphilitics, were given a shameless cosmetic makeover and brought to Hakodate. Hospital ships and military transports that had been “honorably” crippled in the Russo-Japanese War and abandoned like fish guts turned up in port looking more faded than ghosts. If steam was turned up a little, pipes whistled and burst. When they put on speed while chased by Russian patrol boats, the ships began to creak all over as though about to come apart at any moment, and shook like palsied men.

But none of that mattered in the least, for this was a time when it was everyone’s duty to stand tall for the Japanese Empire. Moreover, the crab cannery ships were factories pure and simple. And yet factory laws did not apply to them either. Consequently, no other site offered such an accommodating setting for management’s freedom to act with total impunity.

House of the Dead

The manager knew even better than they did just how much abuse a human body could tolerate. At the end of the workday, workers dropped sideways into their bunks like logs, groaning, “Maybe this is it…”

One of the students recalled being taken to a Buddhist temple by his grandmother as a child, and seeing in its dim hall paintings of hell that looked just like this. Their present situation strongly reminded him of a great snakelike animal he had seen slithering through a marshland. It was the spitting image of it. The overwork perversely robbed them of their ability to sleep. After midnight, in various parts of the shit-hole there suddenly arose the eerie sounds of teeth grinding as if chewing up glass, of nonsensical words, and wild shouts.

When they could not sleep, they sometimes whispered to their own bodies: “I can’t believe you’re still alive…” I can’t believe you’re still alive – to their bodies!

It was the hardest on the students.

“Looking at it from our current perspective, I get the feeling those convicts in Dostoyevsky’s House of the Dead didn’t have it so tough after all,” said a student who hadn’t been able to shit for days and could not sleep unless he tied a hand towel tightly around his head.

|

Mother of success

The foreign movie was American and dealt with the history of “developing the West.” Though relentlessly attacked by savages and struck down by merciless nature, settlers bounced back to their feet and went on extending the railroad yard by yard. Along the way towns were erected overnight, springing up like railway spikes. And as the railroad advanced, more and more towns kept cropping up. The movie showed the manifold hardships that arose from all this, weaving into the narrative a “love story” of a laborer and a corporation director’s daughter. As the movie reached its final scene, the benshi’s [screen-side narrator’s] voice rose to a pitch: “And so, thanks to young people’s countless sacrifices, the endlessly snaking railroad succeeded at last in sprinting across the plains and piercing the mountains to transform yesterday’s wilderness into today’s national wealth.”

The movie climaxed with an embrace between the corporation director’s daughter and the laborer, who had magically mutated into a gentleman.

This was followed by a short foreign film, mindless buffoonery that made everyone laugh.

The Japanese feature told of an impoverished youth who sold fermented soybeans and evening papers before going on to shine shoes, enter a factory, become a model worker, be promoted, and end up a multimillionaire. “Truly, if hard work is not the mother of success, what is!” exclaimed the benshi, inserting words that did not appear in the subtitles.

Young workers greeted his comment with earnest applause. But someone among the crowd of fishermen and sailors shouted loudly, “What a crock of shit! If that were true, I’d be a company president by now!”

This brought a huge burst of laughter from everyone.

Once the laughter subsided, the benshi explained that the corporation had ordered him to stress the “mother of success” message strongly and repeatedly.

As a final segment they saw footage of all the corporation’s factories and offices. It showed countless workers, all working industriously.

Looking for trouble

After supper the cabin boy came down into the shit-hole. Men were sitting around the stove and talking. Some stood under the dim light picking lice from their shirts. Each time their bodies blocked the light, the men cast great oblique shadows on the painted, sooty bulkheads.

“Let me tell you what the officers, captain, and the manager are up to. It looks like we’re going to be sneaking into Russian territory to fish there. And so the destroyer’s going to stick close to us all the time and guard us. They’re going to be making lots and lots of this.” He made a circle with his thumb and forefinger in the shape of a coin.

“They’re saying that Kamchatka and northern Karafuto are rolling with money to be made, and they’re making damned sure to add this whole area to Japan. They say this region is just as important to Japan as China and Manchuria. On top of that, it seems that this corporation’s gotten together with Mitsubishi to nudge the government along. If the company president gets into the Diet at the next election, they’ll really be stepping things up.

“And so they say the destroyer’s been sent to guard the cannery ship, but it turns out that’s not the main reason. They’re going to carry out a detailed survey of the sea around here, northern Karafuto, and Chishima Islands, and to study the climate. That’s the big objective and it has to be carried out thoroughly. I guess it must be a secret, but it seems they’re quietly moving artillery and fuel oil to the northernmost of the Chishima Islands.

“It bowled me over when I first heard it, but when you come right down to it the truth is that every single one of Japan’s wars to this day was fought at the orders of a few rich or super-rich men (I’m talking really rich men), with the excuses cooked up any which way. Anyhow, these crooks are itching like crazy to get their hands on every place they smell money. They’re looking for trouble.”

Masters and slaves

In a lower bunk, Shibaura talked waving his arms. The Stuttering Fisherman rocked back and forth, nodding at his words.

“… See? Let’s suppose the ship exists because the rich put up the money and had it built. If there were no sailors and stokers, could the ship move? There’re hundreds of millions of crabs on the bottom of the sea. Let’s suppose we all got our gear and came out here because the rich were able to put up the money. But if we didn’t work, would even one solitary crab end up in the pockets of the rich? See? Now, think about how much money’s coming our way after we work here all summer. Yet from this ship alone the rich will snatch four or five hundred thousand yen of pure profit. Well, we are the source of that money. Nothing comes out of nothing. You see? Everything’s in our power. And so I’m telling you to wipe that gloomy look off your mug. Show them who you are. In their heart of hearts they’re scared shitless of us, and that’s no lie. So don’t be timid.

“Without sailors and stokers, ships wouldn’t budge. Without the workers’ labor, not one lousy penny would roll into the pockets of the rich. Even the money to buy the ship, to outfit and equip it, comes out of profits wrung from the blood of other workers. It’s money that’s been squeezed out of us. The rich and we are masters and slaves…”

|

A rolling snowball

Triangular waves came rushing at the ship. Fishermen accustomed to the Kamchatka Sea instantly knew what that meant.

“No fishing today, way too dangerous.”

An hour went by.

Men stood around in groups of seven or eight under the fishing boat winches. The boats swung in the air, each lowered only halfway. Men shrugged and argued gazing at the sea. A few minutes went by.

“I quit! I quit!”

“They can go fuck themselves!”

It was as if they had been waiting for somebody to say it.

As they jostled and milled about, someone else said, “Hey, let’s pull the boats back up.”

“Yes!”

“Yes, a damn good idea!”

“But…” A man looked up at the winch and hesitated, frowning.

“If you want to drown, go out there by yourself!” said another scornfully, turning away with a jerk of his shoulder.

The whole group began to leave. “I wonder if this is really OK,” whispered someone. Two men uncertainly lagged behind.

At the next pair of winches too fishermen stood motionless. Seeing the crew of Boat Number 2 walking toward them they understood what it meant. Four or five of them waved and raised their voices:

“We’re quitting! We’re quitting!”

“That’s right, time to quit!”

As the two groups met, their spirits rose. Two or three men who were not sure what to do looked on, baffled. The newly formed group moved on to join the crew of Boat Number 5. Seeing this, the men who had been hanging back started to walk forward, grumbling.

The Stuttering Fisherman turned around and shouted loudly, “Be tough!”

Like a rolling snowball becoming larger and larger, the group of fishermen kept on growing. The Stuttering Fisherman and the students ran constantly back and forth between the group’s front and its rear. “All right, all right, don’t let yourselves get separated! That’s the most important thing. Stay together and we’re safe. That’s it, now we’re good!”

Fishermen who sat in a circle mending ropes near the smokestack straightened their backs and called out, “Hey what happened?”

The advancing group lifted their arms toward them, and raised a great shout. Sailors watching from above saw a forest of waving arms.

“Good, that does it! We’re stopping work.”

They briskly began to put away the ropes. “We’ve been waiting for this!”

The fishermen understood. Once more they raised a great cry.

“First of all, let’s get everyone out of the shit-hole. Yes, let’s do it. That motherfucker knows damn well that a storm’s coming up, and he still has the nerve to order the boats out! What a fucking murderer!”

“Damned if we’re going to let him kill us!”

“Now he’ll see who he’s been messing with!”

|

On the side of the people?

It was starting to grow dark when a fisherman who had been keeping watch from the hatchway spotted the approaching destroyer. Agitated, he rushed to the shit-hole.

“Damn it to hell!” The student leapt up like a spring. His face turned deathly pale.

“Don’t jump to any wrong conclusions,” said the Stuttering Fisherman with a laugh. “Once we win over the officers with a full explanation of our situation, viewpoint, and demands, this strike will turn out even better. That’s as plain as day.”

“That’s true,” said others in agreement.

“That’s our own imperial warship out there. It’s got to be on our side, on the side of the people.”

“No, no…” The student waved his hand. He seemed shaken by a powerful shock. His lips were trembling, and he was stammering. “On the side of the people? … No, no…”

“Look, you idiot! How the hell can a warship that belongs to the empire not be on the side of the people who belong to that same empire?!”

“The destroyer’s here! The destroyer has arrived!” Excited voices drowned out the student’s reply.

Everyone bounded out of the shit-hole and onto the deck. Voices suddenly joined in a great shout: “Imperial navy, hurrah!”

The manager, his face and hand bandaged, stood at the top of the gangway together with the captain and a few others. Directly opposite them stood the Stuttering Fisherman, Shibaura, Don’t-act-big, students, stokers, seamen, and the rest of the men. Dimly visible in the gathering darkness, three steam launches left the destroyer. They drew up alongside the cannery ship. Each launch was packed with about sixteen uniformed sailors. All at once the sailors rushed up the gangway.

“Hey! They’ve got fixed bayonets! And they’re wearing helmets!”

“Oh hell!” cried the Stuttering Fisherman voicelessly.

Blood and flesh

Every year as the fishing season drew to an end, it was customary to manufacture some cans of crab meat to be offered to the Emperor. Yet not the slightest effort was ever made to precede their preparation with the traditional ritual purification. The fishermen had always thought this terrible of the manager. But this time they felt differently.

“We’re squeezing our very blood and flesh into these cans. Huh, I’m sure they’ll taste wonderful. Hope they give him a stomachache.”

Such were their feelings as they packed the cans for the Imperial table.

“Mix in some rocks! I don’t give a fuck!”

|

One more time!

“Nobody’s on our side except our own selves.”

This was the feeling that now penetrated deep into everyone’s heart. “We’ll show you soon enough!”

But repeating the phrase “we’ll show you soon enough” hundreds of times brought them no satisfaction. The strike had been miserably defeated, and the work – “Have you learned your lesson, you scum?” – had grown even harsher. The added brutality was the manager’s way of revenge. It exceeded even the most extreme limits. The work had become unendurable.

“We were wrong. We shouldn’t have put nine people out in front of us like that. We might as well have been saying to them, here’s where our vital organs are. We should’ve all acted together, every one of us. That way it would’ve been useless for the manager to radio the destroyer. They sure as hell couldn’t drag all of us away. There’d be nobody left to do the work.”

“That’s right.”

“No doubt about it. If we keep on working like we are now, we’ll really get ourselves killed this time. To make sure nobody has to be sacrificed, we all have to strike together. Let’s take the same approach as before. Like the stuttering guy used to say, the most important thing of all is to join forces. By now we sure know how much we could’ve accomplished that time if we’d stayed united.”

“And if they still call in the destroyer, let’s stay united and get handed over together without leaving anyone behind! That’ll help us even more.”

“You may be right. Though come to think of it, if that happens the manager will be in very hot water with the company. It’ll be too late to send to Hakodate for replacements, and the output will be way down… If we do this right, if might turn out even better than we expect.

“It will work out just fine. Besides, it’s fantastic how nobody’s scared any more. Everybody’s ready to take on the fuckers!”

“Frankly, there’s no sense hoping for some future victory. It’s a matter of life or death right now.”

“Well, let’s do it again, one more time!”

And so they rose. One more time!

Recommended citation: Zeljko Cipris, “To Hell With Capitalism: Snapshots from the Crab Cannery Ship”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 18, No. 2, May 4, 2015.

Komori Yoichi’s introduction to the Crab Cannery Ship is available here.

Related articles

• Heather Bowen-Stryk, Why a Boom in Proletarian Literature in Japan? The Kobayashi Takiji Memorial and The Factory Ship

• Norma Field, Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji’s Cannery Ship

• Zeljko Cipris, Against the System: Antiwar Writing of Kuroshima Denji

• Heather Bowen-Struyk, The Epistemology of Torture: 24 and Japanese Proletarian Literature