Godzilla and the Bravo Shot: Who Created and Killed the Monster?

By Yuki TANAKA

The Creation of Godzilla

The original Godzilla film was produced in 1954 and released in November that year, only nine years after the end of the Pacific War. The same production team produced a sequence of 22 Godzilla films between 1954 and 1995, and six more films were created in the years 1995 to 2004 by a different production team. The original Godzilla film, Godzilla, and its first sequel, Godzilla Raids Again produced in 1955, were the result of close cooperation between Producer Tanaka Tomoyuki, Director Honda Ishiro, Special Effects Director Tsuburaya Eiji, and scriptwriter Koyama Shigeru.

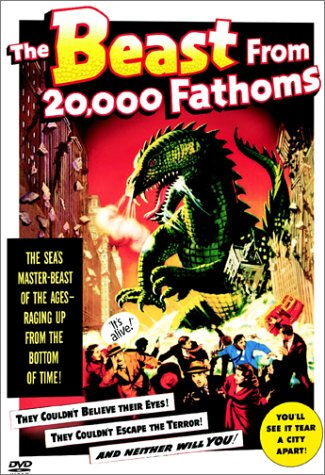

In 1953, Tanaka Tomoyuki, a young film producer working for the Toho Film Studio, was assigned to produce a film entitled In the Shadow of Honor, a Japanese –Indonesian co-production. It was a story about a former Japanese soldier who stayed on following Japan’s surrender and participated in the Indonesian independence movement. However, rising diplomatic tensions between the Japanese and Indonesian governments forced the canceling of the project before filming began. With a substantial sum of money allocated for the project, Tanaka had to find a quick alternative project to utilize this budget to make an attractive popular film. Tanaka was a visionary who later produced some of Kurosawa Akira’s best films such as Yojimbo, Sanjuro, and Aka-hige (Red Beard). Facing this crisis, he decided to take advantage of a recent incident that was had captured the popular imagination. That was the hydrogen bomb test Bravo shot that the U.S. conducted on Rongelap (or Bikini) Atoll in the Marshall Islands in March 1954. The radioactive fallout from the test enveloped a Japanese fishing boat called the 5th Lucky Dragon with deadly effects. Influenced by the popular success in 1952 of the re-release of the 1933 classic film King Kong, Tanaka set out to film a giant monster film like The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, the 1953 American film.

The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms was about a large dinosaur 30 meters in length. The beast, which hibernated during the ice age, thaws out as an American nuclear test conducted at a secret site somewhere in the Arctic Circle melts the icebergs. Unlike Godzilla, this nameless beast does not emit radiation. It is simply a super-large dinosaur. Traveling south, it is carried to New York by an ocean current in the North Sea. Eventually, the monster is killed by U.S. soldiers who launch a deadly radioactive isotope. The film explores the scientists’ doubts about eyewitness accounts by people who actually saw the monster, as well as the process through which existing scientific wisdom proves invalid. The monster embodies a contradiction between scientific knowledge and the unknown power of nuclear weapons. Yet the power of radiation, i.e., new scientific knowledge, resolves this contradiction. In this way the story unfolds in a scientific and logical manner – typically American in style –ending with the victory of nuclear science over the monster.

Tanaka asked mystery storywriter Koyama Shigeru to prepare a script based on the idea that a dinosaur asleep in the Southern Hemisphere, awakened and transformed into a monster by the hydrogen bomb, attacked Tokyo. He asked Honda Ishiro to direct the film. Honda was a close friend who often acted as Kurosawa’s assistant director . During the war Honda had been stationed in China. On his repatriation to Japan he landed at Kure port and then passed through Hiroshima, the city devastated by the A-bomb. Shocked by the devastation, he had wanted to make a film to illuminate the horrors of nuclear war. Honda’s anti-nuclear sentiments brought to Godzilla the strong message of the evil of nuclear weapons and nuclear tests. Tsuburaya Eiji had been involved in making models of war ships, naval ports, military bases and the like which were used in war films produced during the Asia-Pacific War. The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya was one of the films highlighting Tsuburaya’s rare talent in special effects. He was creative, skillful and meticulous in making miniature models. Dr. Yamane, one of the main characters in the first two Godzilla films, was played by Shimura Takashi, who played the samurai leader in Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, which was produced in 1954, the same year as Godzilla.

Godzilla is a dinosaur that survived from the Crestaceous period and lives around a fictitious southern Japanese island called Otojima. Godzilla is deified by the islanders and even used in kagura or local sacred music and dance. In some sense it is similar to Oni (devil) and Daija (big snake), legendary creatures of Japan and China. It is a giant monster 50 meters long (100 meters including its thick tail) weighing 20,000 tons. It appears at the same time as a typhoon and travels a course frequently taken by typhoons that attack Japan. In other words, Godzilla is seen as a kind of “natural phenomenon” similar to a typhoon or “an act of God” that human beings cannot control. Unlike the dinosaur in The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, Godzilla is a malevolent deity or genie. Gojira, the Japanese original name, is a word derived from the combination of “gorira (gorilla)” and “kujira (whale). When the original film was about to be exported to the U.S., Toho came up with the new spelling “Godzilla,” an amalgamation of god, lizard and gorilla.

Unlike The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, the original film Godzilla does not demonstrate the victory of science over nature. Rather it implies that human beings may be destroyed through the impact of science-run amuck-on nature.

In Koyama’s original draft script, the film was to have begun with the following narration:

X day of November, 1952, was a crucial one for mankind. From that day on, the entire world had to live under the immense fear of nuclear tests. The first H-bomb test can be called ‘liquidation’ rather than ‘test’. Can the H-bomb test be contained within the limits of an experiment? No, absolutely No!

Eventually this narration was discarded. Nor did the film include the actual scene of the blast of the H-Bomb. It was unnecessary to give such a direct message, or to show a picture of a nuclear test, as the Japanese audience clearly knew the horrific impact of nuclear arms. In the film people only talk about the H-bomb test. Hearsay without an actual picture, an implied link between the unknown monster and the nuclear test, was far more effective in conjuring the mysterious and fearful impact of radiation caused by the blast.

Destruction of the City

In The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, the beast walks the street, smashing cars or picking them up in its mouth when they get in its way. It destroys only one building, and this by accident when it leans heavily against a building, trying to avoid shots fired by police. People flee, crying that this is war, as the city turns into a battlefield. The film appears to portray all out war between the beast and the city population. Yet the battlefield is confined to a few wide streets in New York City. The beast appears in the city in broad daylight so everyone knows where it is. It attacks only policemen who try to shoot it. A woman screams as she watches a policeman being eaten by the beast. Yet the beast does not attack the woman. In other words, the beast’s attack is not random, indiscriminate assault. It is “precision attack,” on those who try to harm it. Clearly, this film was produced by people with no experience of indiscriminate aerial bombing. The same can be said of other American monster films such as Alien and the Hollywood production Godzilla in 1998 in which the main target of attack by Godzilla is again the people, not the city itself, and the monster and its babies are carnivorous dinosaurs.

The Japanese original Godzilla neither chases nor eats people, but simply attempts to destroy the city completely and thereby kill its inhabitants. Attacking indiscriminately at night, Godzilla smashes everything and breathes radioactive fire. The city is burnt to the ground. The time spent on the scene where Godzilla destroys Tokyo is more than ten times longer than the scene in which the city is attacked in The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms. Tokyo citizens try to escape as far from the metropolitan area as possible, carrying as many personal belongings they can.

Many scenes reminded the audience of aerial bombing of Japanese cities by B-29 bombers in the final months of the Pacific War. For example, on March 10. 1945, an estimated 100,000 people in the Tokyo metropolitan area were burnt to death within a few hours as a result of 237,000 fire-bombs dropped from 334 B-29s. An estimated one million lost their homes and were driven from the city.

Godzilla’s preference for darkness and intense dislike of light evokes the behavior B-29 bombers, which flew at night and sought to evade searchlight beams. From the raid on Tokyo on March 10, 1945, Brigadier General Curtis LeMay, the Commander of the XXI Bomber Command, changed U.S. bombing strategy from precision bombing during the day to carpet bombing with recently developed napalm bombs at night. The U.S. carried out “saturation bombing” until the end of the war in August 1945, repeatedly attacking cities from Hokkaido to Okinawa, including Tokyo, Kawasaki, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Fukuoka and Naha. More than 100 cities were destroyed, causing one million casualties, including more than half a million deaths, the majority being civilians, many of them women and children. Indiscriminate bombing reached its peak with the use of atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, Truman’s claim to the contrary notwithstanding. Of course, many Japanese who saw the original Godzilla film had first hand experience of aerial bombing and had lost relatives and friends as a result.

In one scene, a boy cries “Chikusho (“You brute”), watching Godzilla stalking away towards the ocean from Tokyo Bay after a rampage. This scene vividly reminded the audience of B-29 bombers flying off after dropping tens of thousands of bombs on their urban target. The film includes scenes of people trying to escape carrying household goods, of a burning city, of injured people being brought into a safe shelter, and of screaming children. These pictures evoked the horror of napalm attacks in cities throughout Japan.

A homeless mother tells her small children that they will soon join Daddy in heaven, as they look up at the ferocious Godzilla destroying the Matsuzakaya Department Store in the Ginza. This indicates that the woman is a widow who lost her husband in the war and subsequently became homeless. A Ministry of Welfare survey in 1952placed the number of widows in Japan that year at 1,883,890, 88.4% of of them with children under 18 years of age. 70,000 such households were jobless, struggling to survive, many working as day labourers or peddlers. Thus the film clearly reflects the deep scars of war on Japanese society. Godzilla allowed Japanese to heal their pain through watching an entertaining film which poignantly evoked their recent wartime experiences.

There are almost no scenes in which people are actually killed by Godzilla, although the audience may imagine that many people die under the collapsed buildings, in the burning houses, or in the train carriages that Godzilla picks up and crunches in his mouth. Instead, the film concentrates on the destruction of famous buildings in Tokyo such as the Clock Tower of the Hattori Corporation, Nichigeki Theatre, Kachidokibashi Bridge, the Metropolitan Police Department and the Diet building. The audience clapped joyously when Godzilla destroyed the Diet and Metropolitan Police Headquarters – both symbols of state authority. I presume that many at the time felt that the state and politicians had dragged them into a disastrous war culminating in the U.S. aerial bombardment. In actual fact, the Diet and the Metropolitan Police Department were hardly damaged by the aerial bombing, mainly because they were close to the Imperial Palace. For political reasons, the Imperial Palace was removed from the target list of aerial attacks.

Godzilla as both Victim and Perpetrator of Nuclear Terror

On March 1, 1954, the U.S. conducted a hydrogen bomb test called Bravo shot at Rongelap Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The H-bomb at 15 megatons was 1000 times bigger than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. As a result of this nuclear test radioactive dust fell not only on many Marshall Islanders but famously on a Japanese tuna fishing boat called the 5th Lucky Dragon, irradiating all twenty-three fishermen including Captain Kuboyama Aikichi, who died on September 23 that year. Since then 13 other members of the crew have died from various types of cancer, and those who survive are suffering from the disease. The U.S. conducted four more nuclear tests at Rongelap Atoll that spring, contaminating 856 Japanese fishing boats with radioactive materials.

The effect of these nuclear tests on Japanese, a who had previously experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the heels of the destruction by bombing of virtually all other major cities, was to strengthen anti-nuclear sentiments, giving rising to a powerful anti-nuclear movement that spread across Japan in the form of a citizens’ petition initiated by women opposing nuclear tests. The petition, the largest of its kind ever, was signed by 32 million Japanese. That August, the first Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima. The 5th Lucky Dragon became the model for the boat called “Eiko Maru” attacked by Godzilla. In fact one of the many boats that was showered with radioactive dust in the Marshall Islands was called the 13th Koei Maru. The name “Eiko Maru” undoubtedly was the inversion of the name of this real boat. Popular expressions widely used at the time such as “Genshi maguro” (atomic tuna) meaning ‘irradiated tuna’ and ‘hoshano’ (radioactive fallout), were used in the film.

For example, three office workers – a woman and two men – on their way to work are conversing in the train. The woman says, “It’s terrible, isn’t it? Irradiated tuna and radioactive fallout, and now this Godzilla to top it all off! What will happen if he appears out of Tokyo Bay? Oh awful. I survived the bombing of Nagasaki at great pains, yet I have to go through this again…” One of the men says, “I guess I’ll have to find a place where I can be evacuated again. It stinks, ha!” Thus the fear of radioactive fallout is directly linked to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Godzilla’s appearance is closely linked to the U.S air raids and wartime evacuations.

In short, the original Godzilla film clearly conveyed anti-nuclear messages. Yet the fear of radiation does not really stand out in this film. When Godzilla lands in Tokyo, he burns down buildings and drives away civilians by breathing radioactive fire. But there is little explanation of the effects of radiation. We, in the audience, expect that the places Godzilla passes must be heavily contaminated by radioactivity. After all, the 5th Lucky Dragon Incident shocked so many Japanese not because of thermal rays or the blast, but because of the radioactive dust. In the film, radioactivity is not seriously addressed, but in a few scenes a Geiger counter is used to detect radioactivity.

Posters touted “the H-bomb monster” and “the Super monster that breathes radioactive fire”. So why wasn’t radiation highlighted? The young manager of Nankai Salvage Boat Company, Ogata, confronts the paleontologist, Dr. Yamane, saying “Isn’t Godzilla a product of the A-bomb that still haunts many of us Japanese?” The film as a whole, however, portrays Godzilla as a victim of the H-bomb test rather than the radioactive perpetrator. For example, addressing the Parliamentary Investigation Committee, Dr. Yamane describes Godzilla with a certain sympathy saying:

“Godzilla probably quietly survived by eating deep sea organisms occupying a specific niche. Yet, repeated H-bomb tests may have destroyed his environment completely. To put it plainly, it can be said that Godzilla was forced out of his peaceful living place by H-bombs.”

In this manner, Godzilla is presented as a creature that is being both victim and assailant. Indeed Godzilla is a sad monster that mirrors we human beings, who produce nuclear weapons and at the same time victimize fellow human beings by using them. In particular, the ugly Godzilla symbolically represents the Japanese who were victimized by A-bombs and H-bombs, yet whose government not only supports U.S. possession of nuclear arms but also contributes to US war making in Korea. In the end, Godzilla appears more victim than assailant. This resonated with the widely held Japanese self-image as victim of aerial bombing that destroyed many Japanese cities including Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was an image that elided the fact that Japanese Imperial Forces invaded China and conducted indiscriminate bombing of civilians on many Chinese cites such as Shanghai, Nanjing, Wuhan and Chongqing during the fifteen year war that culminated in the Asia Pacific War.

Nevertheless, given this dual character, Godzilla is not simply a dinosaur. He is a heretic or a rebel, like some of us, who violently struggle to solve the contradiction of duality. Although a small child when I saw the original Godzilla film, I clearly remember feeling sad seeing Godzilla finally die in agony. This was quite different from the emotion that I had two years later in 1956 when I watched another film called Radon, about a flying monster, that leapt out of a lake. I was so scared of Rodon that I could not take a bath for some time afterwards, recalling that frightening scene.

The Godzilla film highlights the fact that as producers of nuclear arms we human beings are the assailants of Godzilla, i.e. ravagers of the natural environment, but also that nature will exact revenge on human beings who have unlocked the brutal power of science.

The original Godzilla film introduces many other scenes that reflect contemporary political problems such as the cold war, the Korean War, the remilitarization of Japan, as well as the Japanese fear of being dragged into war again. Thus the film evokes not only anti-nuclear sentiments but also strong anti-war feelings.

The American Godzilla Films

The first Godzilla film produced in the U.S. was Godzilla: King of the Monsters. This 1956 production used many clips from the original Japanese film and combined them with inserts made by Producer Joe Levine and Director Terry Morse. Raymond Burr starred as Steve Martin, an American newspaper journalist who reports on Godzilla.

This film, however, fails to explain how the radioactive Godzilla was created. The American audience never learns that the monster was the by-product of an H-bomb test conducted in the Pacific by their own country. Many scenes considered unsuitable for an American audience were revised or omitted. For example:

1) In the Japanese original, Dr. Yamane is intrigued by Godzilla’s extraordinary strength and ability to survive the H-bomb test and sets out to find out why. In the American film, Dr. Yamane simply wants to investigate Godzilla as a rare monster.

2) In the original, a Geiger counter measures the level of radioactivity of injured people. This scene naturally led Japanese viewers to recall the immediate aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the firebombing of scores of other cities. The American version simply states that people died from strange burns.

3) In the original, a Geiger counter is used to locate Godzilla, whereas in the American version, a sonar (i.e. sonic depth finder counter) is used.

4) The American version omits the conversation among office workers on the train, including the woman’s statement “I survived the bombing of Nagasaki at great pains.”

5) In the original film, Dr. Yamane’s dark last words are, “If we keep conducting nuclear tests, another Godzilla might appear somewhere in the world, again!” The American version replaces these words with Steve Martin’s statement, “The menace is gone. The world can wake up and live again!”

In short, Producer Joe Levine and Director Terry Morse avoid dealing with the nuclear issue. In this film Godzilla is a mysterious monster whose origins are unknown. The film suggests that when the monster dies, it is best to forget about it as quickly as possible. When Dr. Yamane’s daughter, Emiko, asks Steve, why they have to face such a dreadful problem, he responds simply, “I don’t know, Emiko, I don’t know.”

The original Japanese story flows naturally without narration. By contrast, the American version is framed entirely by newspaper correspondent Steve Martin. For Steve Martin, Japan is simply the source of a mysterious story. He observes the events there without any real concern and makes no effort to help the Japanese people struggling with the problem of Godzilla. Basically he is uninterested in the crisis facing the Japanese nation. He simply reports superficially on what is happening. Steve is said to be a friend of Dr. Serizawa, who graduated from the same American university. Yet, he smokes a pipe dispassionately, observing his friend and other Japanese people with indifference.

The second American Godzilla film, simply entitled Godzilla and produced in 1998, is the story of an iguana that was irradiated by a French nuclear test at Muraroa Atoll and somehow appears in New York as Godzilla. France in fact resumed nuclear testing with the 20 kiloton blast in the South Pacific in 1995. For Americans, monsters like Godzilla and King Kong must come from a distant uncivilized world. As far as American film studios are concerned, it would seem that Godzilla must not be created by American nuclear tests. This film opens with a scene in which an American scientist, Dr. Niko Tatopulos, is investigating giant earthworms deformed by radioactivity leaked from the Chernobyl accident. It is well known that there have been many cases of cancer and leukemia among people living in areas adjacent to the Chernobyl Power Plant. Dr. Tatopulos, however, seems unaware or uninterested in the human problems caused by the nuclear power plant accident at Chernobyl. Still less is he interested in the effects of the nuclear disaster much closer to home at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, where many deformed flowers and leaves were found in areas close to the power plant.

Unlike the Japanese Godzilla, the American Godzilla is simply a giant dinosaur that eats huge quantities of fish and lays many eggs while its babies attack and cannibalize human beings. Godzilla runs around the streets of New York, chasing people in a car that had tried to destroy its eggs. It does not randomly destroy buildings and commit mass killings. The American Godzilla does not breathe radioactive fire, and is eventually killed not by nuclear arms but by conventional weapons. Apart from a few early scenes, the American film does not refer to nuclear issues at all. It is more appropriate to call it an expanded version of Jurassic Park rather than Godzilla. In other words, the 1998 Hollywood production de-politicized, de-nuclearized, and de-Japanized Godzilla, at the same time transforming Godzilla into a giant reptile simply controlled by animal instincts. The American Godzilla has been stripped of its vital elements of rebellion, contradiction, heterodoxy, and social criticism.

The American Godzilla films lack another crucial element present in the Japanese original, the scientists’ moral dilemma. In the original Japanese film, Dr. Serizawa accidentally comes across an unknown form of energy in the course of his research on oxygen. Eventually, he invents a lethal device called the oxygen destroyer. Even a small baseball-sized oxygen destroyer can kill the entire population of sea organisms in Tokyo Bay by depriving them of oxygen. In other words, this is a weapon as powerful as the H-bomb. This places Dr. Serizawa in an agonizing moral dilemma. He knows he could use it to annihilate Godzilla, but there is also the danger that the weapon could subsequently be abused by others. Should he therefore keep it a secret? Eventually he decides to use it against Godzilla, but to commit suicide immediately after destroying Godzilla so that knowledge of oxygen destroyers would not survive. In this sense, he shares Godzilla’s fate of duality as both victim and perpetrator. Incidentally, Dr. Serizawa wears a black eye-patch on his right eye and his right cheek has a big burn scar, indicating that he was a victim of a napalm-bomb or atomic bomb attack by the U.S. forces during the war. Many Japanese emerged from the war with keloidal scars on various parts of the body as a result of aerial bombing.

In short, the original Japanese film contains a powerful and thought-provoking critique of the development and deployment of nuclear weapons. It is worth noting that it was not military forces like the U.S. Air Force or Japan’s Self Defense Forces that finally killed the original Godzilla. Godzilla dies at the hands of a scientist who also chose to kill himself in an effort to save humanity from the dangers of his discovery.

Conclusion

Many other Godzillas have been produced in Japan since 1954, but from the 1960s Godzilla rapidly lost its power of social realism. (An important exception is Godzilla vs. Hedra of 1971, which explores Japan’s pollution problems like Minamata Disease.) Godzilla became a good guy who wrestles against bad monsters and always wins. In other words, it became a pet Godzilla. Yet a pet Godzilla is no longer a monster. A monster is only entitled to be a monster because of an unpredictability that surpasses our imagination. A monster should have a future that includes the possibility that it will rebel against the corrupt and wretched world. Failing that, it should be terminated. For me, a pet Godzilla is the product of the imaginaton of Japanese parents – i.e. kyoiku mama and papa (educationally ambitious mothers and fathers) – as well as of the Japanese school system that moulds obedient children, depriving them of imagination. The taming of Godzilla anticipates the loss of imaginative and creative powers by Japanese adults.

In more recent Godzilla films, the main character is no longer Godzilla. For example, in films such as Godzilla vs. Mecha-Godzilla, Godzilla vs. Space-Godzilla, and Godzilla vs. Destroyer, it is the so-called “G Force” (said to be the Self Defense Forces) that drives the story. The G Force builds military robots to fight against Godzilla, or creates a device to control Godzilla’s nerve system by shooting into Godzilla’s body. It is not surprising that this kind of film is produced as the SDF now demands that their own ideas be included in the script in return for providing tanks, jet fighters and the like for the filming. Is this not the mirror of an age in which the SDF sallies forth in support of U.S. forces in Iraq, and Article 9, the peace provision of the Constitution, is left in tatters?

6. The SDF replaces Godzilla as the main character about here

Well, who killed Godzilla? My answer is that it is we Japanese who appear to have lost the will to confront injustice and inhumanity and to recognize the ambiguities inherent in the new technologies of destruction. Let us revive the real Godzilla in our minds!

Yuki Tanaka is research professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute, a Coordinator of Japan Focus, and author of Japan’s Comfort Women. Sexual slavery and prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation. He prepared this article for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus June 13, 2005.

For another view of the representation of World War II in anime see Susan J. Napier, World War II as Trauma, Memory and Fantasy in Japanese Animation