The Futenma Base and the U.S.-Japan Controversy: an Okinawan perspective

Yoshio SHIMOJI

Introduction

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the conclusion of the revised Japan-U.S. Mutual Security Treaty (Ampo). The original treaty was signed on September 8, 1951, the same day the San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed. One of its provisions stipulated that Japan must guarantee the U.S. the same stable use of military bases as it did under the occupation. Without accepting that requirement, Japan could never have won its independence.

|

Yoshida Shigeru signs the San Francisco Treaty for Japan

Dean Acheson signs the San Francisco Treaty for the United States

|

This stipulation was carried over to the revised Mutual Security Treaty of 1960 (Article 6) and with it the U.S. has been assured of its continued formidable military presence in Japan, dominating its sea, land and air space to this day.

Japan’s independence was also achieved at the cost of Okinawa, which was kept under harsh military administration until the reversion of its administrative rights to Japan in 1972. But even after reversion, the U. S. bases in Okinawa remained intact. Today, the negative side of the Japan-U.S. Mutual Security Treaty appears most conspicuously in Okinawa, where 75 percent of U.S. bases and facilities in Japan are concentrated. Although those bases and facilities (totaling 85 in number, and 31,000 ha in area) are formally offered to U.S. Forces under the Security Treaty, they are in essence spoils which U.S. forces won in war.

From Okinawa’s perspective, Japan’s independence appears only an illusion. Japan is still a semi-independent or client nation unable to challenge Uncle Sam’s demands; hence, Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio’s wish list in his inaugural speech showcasing, among other things, the desire to make Japan a partner equal to the U.S.

Early history of Ginowan City

The U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, currently a hot issue straining the Japan-U.S. relationship because of the dispute over its relocation, is located in the middle of densely populated Ginowan City. Houses cluster closely around the fences close together, even abutting the approach lights on both sides of the runway. This unbelievable situation has something to do with the city’s post-war history.

While the battle was still going on in the south, the invading U.S. Army encroached upon large swaths of land in the central part of the island, where villages, farmland, school yards and cemeteries existed cheek by jowl with each other. The people who surrendered or survived the battle were herded into concentration camps, mostly in the north.

When they were allowed to return home a few years after the war ended, many people from central Okinawa found their hometowns and villages turned into vast military bases. Reluctantly, they began to live alongside barbed-wire fences, some earning a meager livelihood by working for the bases. This is how Ginowan City, which now surrounds the Futenma Air Station, came into being [1].

|

Futenma Air Station occupies 25% of densely populated Ginowan City |

In response to the strong demand of the residents of Ginowan for its closure because of various hazards it poses, Japan and the U.S. struck a deal in 1996 to close the base and return the land when a suitable relocation site was found elsewhere on the island.

Henoko as a site for relocation

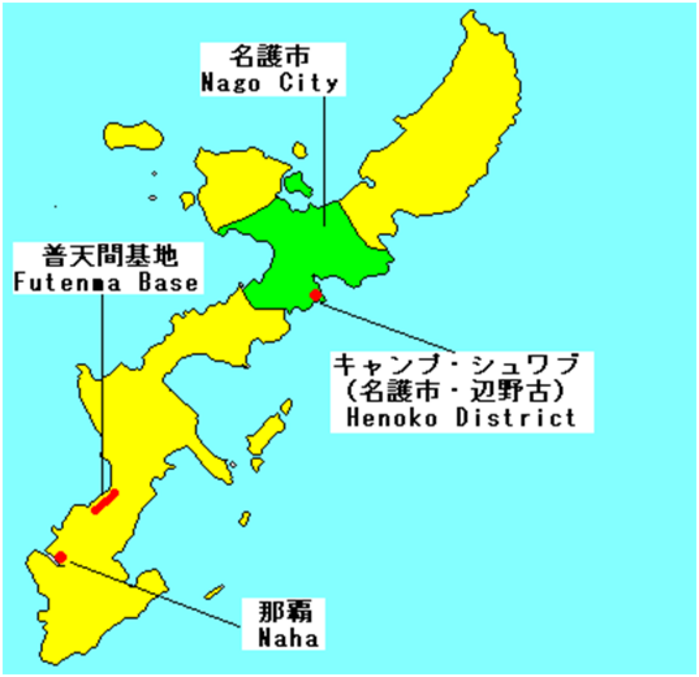

Apparently, from early on, the U.S. had Henoko in mind as a site for the relocation. The Marine Corps Okinawa submitted a blueprint every fiscal year to the Pentagon and eventually to the U.S. Congress for approval in the 1960’s, with an air station and port facilities to be constructed on reclaimed land off the coast at Henoko. Whether it would be a replacement for Futenma or an outright new air base is not clear, but the design for its functions was the same as the current V-shaped runway plan set forth in the United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation agreed in 2006 (hereafter called 2006 Road Map): to integrate the newly constructed air base with Camp Hansen, Camp Schwab and the central and northern training areas, thus strengthening military functions (as had been the plans for Okinawan bases during the Vietnam War) and deterrence capability against North Korea, China or Russia today [2].

|

Map showing Futenma and Henoko sites |

However, the ’60’s plan didn’t materialize, probably because the U.S. Congress didn’t pass the bill for the necessary appropriations due to skyrocketing expenditure on the Vietnam War, as Masaaki Gabe suggests [3], or because U.S. lawmakers were afraid the whole project would prove useless if Okinawa were returned to Japan in the future. The situation is totally different today, however. If all goes according to Pentagon plans, Tokyo will shoulder all the expenses for land reclamation and the construction of runways and other facilities, not to mention the high-end equipment, as well as the cost of relocating thousands of US troops to Guam.

The Futenma issue started as part of the 1995 Special Actions Committee on Okinawa (SACO) initiative to reduce burdens on Okinawa. But fifteen years later, the burdens remain as heavy, nor will they be lightened if Futenma’s operations are moved to another location within Okinawa. Moving the base around in Okinawa or, more broadly, in Japan will clearly signal that Tokyo has yet again consented to a permanent U.S. military presence or “a life-of-the-alliance presence for U.S. forces” in Japan (2006 Road Map) , a transparent cover term for the unlimited occupation of Japan. This must be prevented by all means. This is the essential issue concerning Futenma, one which cuts to the very heart of the U.S-Japan strategic alliance.

Marines and Washington’s explanation

Washington persists in saying that Henoko is the best site for the relocation of Futenma if Japan wishes to continue to maintain the American military deterrence capability, warning that contingencies could occur in the Pacific region, for example, in the Korean Peninsula or the Taiwan Straits, requiring the Marines’ presence as essential deterrence.

On January 6, 2010, the U.S. Marine Corps Okinawa announced its position on the relocation of Futenma. In order to counter contingencies effectively, a helicopter squadron must be deployed within a 20-minute distance from a base where ground forces are standing by. This is why they claim Futenma’s function must be relocated to Henoko, which is adjacent to Camp Schwab and Camp Hansen where the Marines’ ground troops are stationed.

|

Aerial photograph of Cape Henoko |

Note that this is an argument based on tactical rather than strategic reasoning.

According to this explanation, a helicopter squadron must pick up ground troops in 20 minutes and transport them to the frontline in a short span of time (perhaps one hour). But can one realistically imagine such a situation in and around Okinawa Island? Do the Marines think a ground battle similar to the World War II Battle of Okinawa will be replicated in the southern section of this island? Is Okinawa still a war zone in their thinking?

Suppose war occurred in the Korean Peninsula and the Marines from Okinawa successfully landed there in one hour. Would 17,000 Marines go into battle against North Korea’s 1.2 million standing army? The same issue pertains to the Taiwan Straits. As is well known, China has a 1.6 million regular army. Or can they function as a bulwark against potential missile attacks, say, by North Korea, China or Russia?

Of course, the Marines alone may not work as deterrents against outside threats; they may be an integral part of the USF Japan together with the Navy and the Air Force. However, if contingencies occurred in the Korean Peninsula or in the Taiwan Straits, they would certainly have to increase their number substantially, probably to 500,000 troops at a minimum. But assembling troops takes several weeks or even months as the Persian Gulf War and the initial stage of the Iraq War demonstrated.

Consequently, the explanation by the Marines and Washington that a helicopter squadron must be deployed within a 20-minute distance from a base where ground forces stand by and, therefore, the claim that Henoko is the best relocation site for Futenma’s operations lacks credibility.

The Marines aren’t here to defend Japan

The Okinawan press reports that Camp Hansen (Kin) and Camp Schwab (Henoko) are both empty shells these days because their occupants were deployed to Iraq and now to Afghanistan to fight against insurgents there.

Obviously, the U.S. Marines or the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force, to be more specific, are stationed in Okinawa not to defend Japan as ballyhooed but simply to hone their assault skills in preparation for combat elsewhere. It’s a cozy and easy place to train, with Tokyo providing prodigious financial aid, which Washington demands in the name of “host nation support.” I liken it to turf dues exacted by an organized crime syndicate, which offers protection from rival gangs.

In 2003, for example, Japan’s direct “host nation support” amounted to $3,228.43 million or $4,411.34 million if indirect support is added. Compare these figures with Germany’s and Korea’s support. Germany’s direct host nation support in the same year was $28.7 million (1/112th that of Japan) and indirect support $1.535.22 million. Korea’s direct host nation support in that same year was $486.31 million (about 1/7th that of Japan) and indirect support $356.5 million [4].

For ten years from 2001 through 2010, Japan shouldered an average annual sum of $2,274 million for host nation support [5], which incidentally is known as “sympathy budget” as if Japan were voluntarily doling out money out of compassion for those U.S. service members who are deployed in this far-away country. The amount Japan has financed to support USF Japan operations since the system started in 1978 totals an astounding $30 billion.

That the Marines are based in Okinawa not to defend Japan but mainly to strengthen U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific and beyond is widely recognized, as the following quotation from GlobalSecurity.org suggests:

“The Regiment (3rd Battalion 6th Marines) continues to support the defense of the Nation by maintaining forces in readiness in support of contingency operations and unit deployments to the Mediterranean, Pacific rim and around the globe.”(Italics mine)

Pundit Kevin Rafferty is more direct saying, “some of the bases (in Japan) are staging-posts for deployment in Afghanistan and elsewhere [6].”

When Marine contingents were compelled to move out of Gifu and Yamanashi Prefectures in mainland Japan in the face of mounting anti-U.S. base demonstrations and moved to Okinawa in the 1950’s, a number of Pentagon strategists are reported to have cast doubt on the wisdom of such a shift.

The U.S. Army was the major element in the U.S. Forces in Okinawa during the occupation period which ended in 1972 with reversion. Apparently, the Army recognized the limited value of being stationed in Okinawa and so withdrew, leaving behind only a few hundred troops. The Marines grabbed this chance to expand their role and function, taking over everything from the departing Army. They are not, however, deterrents against outside “threats” as they boast.

Guam Integrated Military Development Plan

Washington has remained adamant in insisting that Futenma’s operations be moved to Henoko. On meeting Foreign Affairs Minister Okada Katsuya in Tokyo last October, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates urged Tokyo to implement the agenda specified in the 2006 Road Map as soon as possible.

In return, Washington would relocate to Guam 8,000 (later modified to 8,600) Marine personnel, consisting mostly of command elements: 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force Command Element, 3rd Marine Logistics Group Headquarters, 1st Marine Air Wing Headquarters, and 12th Marine Regiment Headquarters. The remaining Marines in Okinawa would then be task force elements such as ground, aviation, logistics and other service support members.

Japan agreed under pressure to fund $6.09 billion of the estimated $10.27 billion for the facilities and infrastructure development costs — another example of extortion. Upon completion of the relocation of Futenma’s function to Henoko and the transfer of the Marine command units to Guam, the U.S. would return six land areas south of Kadena Air Base, including the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma. In trying to sell this package, Washington claims that this reduces Okinawa’s burdens tremendously.

Note, however, that these lands will be returned only if their replacements are found somewhere within Okinawa: for example, Henoko for Futenma, the very question which is straining the bilateral relationship. The 2006 Road Map clearly states: “All functions and capabilities that are resident in facilities designated for return, and that are required by forces remaining in Okinawa, will be relocated within Okinawa. These relocations will occur before the return of designated facilities.”

This is the gist of the 2006 agreement particular to bases on Okinawa. However, a curious situation has developed over the U.S. Forces realignment. Two months after the 2006 Road Map was agreed, the U.S. Pacific Command announced the Guam Integrated Military Development Plan, and on September 15, 2008 the Navy Secretary, who also represents the Marines when dealing with Congress, submitted a report titled “Current Situation with the Military Development Plan in Guam” to the Chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Armed Services [7]. In April 2008, this plan was entirely incorporated into the “Guam Integrated Master Plan,” and in November, 2009 a public hearing was held on a “Draft Environmental Impact Statement/ Overseas Environmental Impact Statement [8].”

These documents show that the U.S. military considers Guam strategically most important in the Asia-Pacific region and plans to transform already existing bases there into a colossal military complex by expansion and development. The U.S. military’s strategic thinking is apparently motivated by the rise of China, particularly by China’s development of new types of long-range missiles. The plan includes re-deploying 8,600 Marines now stationed in Okinawa and relocating most of the Marine capabilities, including helicopter and air transport units in Futenma, to Guam.

A Conundrum

How should we interpret this situation: Futenma’s relocation to Henoko so urgently demanded by the U.S. government, on the one hand, and the U.S. military’s Guam military development plan in which most of Futenma’s operations are to be moved to Guam, on the other? What is the current obfuscation all about?

One answer may be that the U.S. government is manipulating the situation in order to retain every right to a permanent military presence in Japan. This suggests that U.S. policymakers mistrust Japan and the Japanese people despite repeated statements that Japan is the U.S.’s most important ally. In other words, their “deterrence” is not only directed against North Korea, China or Russia, but also against Japan.

When the Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many expected a substantial reduction of the U.S. footprint on Okinawa. The drawdown of U.S. troops in Europe augured well for Okinawa, or so it seemed to me. Then came the 1995 Nye Report and the new US policy based upon it, shattering Okinawan hopes and expectations. On the pretext that the U.S. military presence was a driving force for keeping peace and prosperity in this allegedly volatile region, it announced that the U.S. would continue to maintain bases and troops in East Asia at approximately the same level as before.

William Cohen, Secretary of Defense under the Clinton administration, thwarted our hopes around 2000, when the two Koreas seemed to be reducing tensions on the peninsula and even, perhaps inching to reunification, by saying that there would be no U.S. military withdrawal from Okinawa even if peace was established in a unified Korean Peninsula.

That the U.S. intends to perpetuate its military presence in Japan is evident from its insistence that not only Futenma’s operations be transferred to a new high tech base at Henoko, but also that other facilities such as Naha military port, whose return was promised years before Futenma, must be relocated within Okinawa. The 2006 Road Map betrays Washington’s real intention by accidentally stating, “A bilateral framework to conduct a study on a permanent field-carrier landing practice facility will be established, with the goal of selecting a permanent site by July 2009 or the earliest possible date thereafter.” (Italics mine)

The Defense Ministry’s bureaucrats and their close associates at the Ministry-affiliated National Institute for Defense seem well aware of Washington’s designs, for their East Asia Strategic Review 2010 is written on this unspoken premise.

Concluding Remarks

As suggested above, the Futenma relocation issue is grounded on political rather than military foundations, and the party most responsible for this confusion is the U.S. government, not the Hatoyama government, despite the latter’s ham-fisted handling of the matter. U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma should be closed down and the land returned to its legitimate owners unconditionally and without delay in accordance with the overwhelming wish of the Okinawan people. The U.S. has no inherent right to demand a quid pro quo in exchange for its return. Military training can be conducted on the vastness of U.S. soil with impunity and to their satisfaction.

Yoshio Shimoji, born in Miyako Island, Okinawa, M.S. (Georgetown University), taught English and English linguistics at the University of the Ryukyus from April 1966 until his retirement in March 2003. This is a revised and expanded version of an article posted at the website of Peace Philosophy Centre.

Recommended citation: Yoshio Shimoji, “The Futenma Base and the U.S.-Japan Controversy: an Okinawan perspective,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 18-5-10, May 3, 2010.

Articles on related themes:

Gavan McCormack, The Travails of a Client State: An Okinawan Angle on the 50th Anniversary of the US-Japan Security Treaty

Kikuno Yumiko and Norimatsu Satoko, Henoko, Okinawa: Inside the Sit-In

Urashiima Etsuko and Gavan McCormack, Electing a Town Mayor in Okinawa: Report from the Nago Trenches

Iha Yoichi. Ginowan City Mayor Iha Yoichi’s letter to U.S. President George W. Bush dated October 15, 2003 (Japanese and English). Posted at Ginowan City home page.

Tanaka Sakai, Japanese Bureaucrats Hide Decision to Move All US Marines out of Okinawa to Guam

Gavan McCormack, The Battle of Okinawa 2009: Obama vs Hatoyama

Hayashi Kiminori, Oshima Ken’ichi and Yokemoto Masafumi, Overcoming American Military Base Pollution in Asia: Japan, Okinawa, Philippines

See also: the Peace Philosophy Center, particularly the two articles posted on March 16, 2010 entry on recent plans for a new offshore base and plans for a naval base and casino.

Notes

[1] Land seizure was not limited to central Okinawa; in fact, it was almost universal throughout the island at the time. If that was the first wave of land seizure, the second one started in the early 50’s, hard hitting Iejima, where 35.3 percent of the island’s land area is still military, the Isahama district of Ginowan and the Gushi district of Oroku (later incorporated with Naha City). Land expropriation was brutally undertaken, as Ota (1995) writes: “In some cases during the 1950’s, bayonets and bulldozers were used to expropriate Okinawans’ land and uproot owners from their homes.” It was indeed a flagrant violation of the Hague Convention (Article 46), which clearly states: “Family honour and rights, the lives of persons, and private property, as well as religious convictions and practice, must be respected. Private property cannot be confiscated.”

[2] The Ryukyu Shimpo, June 4, 2000 (morning edition): pages 1 and 7. Also, The Okinawa Times, June 3, 2001 (morning edition): pages 1, 3 and 21.

[3] The Ryukyu Shimpo (ibid.): page 7.

[4] See the U.S. Defense Department’s 2004 Statistical Compendium on Allied Contributions to the Common Defense.

[5] Japanese Ministry of Defense web site.

[6] The Japan Times: April 27, 2010.

[7] Ginowan City Home Page.

[8] Yoshida. 2010.

References

Ginowan City. 2010. “Possibility of Futenma’s Relocation to Guam,” Mayor’s explanatory document prepared for the Meeting on Okinawa’s Military Base Problems held December 12, 2009. Home page.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2006. “United States-Japan Roadmap for Realignment

Implementation”

McCormack, Gavan. 2007. Client State: Japan in American Embrace (Japanese translation). Gaifusha: Tokyo.

Ota, Masahide. 1995. Essays on Okinawan Problems (English). Yui Publishing Company: Okinawa.

____________. 2004. Discrimination against Okinawa and the Pacific Constitution (Japanese). BOC Publishing Company: Tokyo.

The National Institute for Defense. 2010. “East Asia Strategic Review 2010” (Japanese).

Rafferty, Kevin. 2010. “Hatoyama’s fate tied to Futenma” in the April 27, 2010 Japan Times.

The Okinawa Times, June 3, 2001 (morning edition)

The Ryukyu Shimpo, June 4, 2000 (morning edition)

U.S. Department of Defense. 2004. “2004 Statistical Compendium on Allied Contributions to the Common Defense”.

Yoshida, Kensei. 2007. Okinawa: The Military Colony (Japanese). Kobunken: Tokyo.

____________. 2010. Okinawa-Based Marines will Go to Guam (Japanese). Kobunken: Tokyo.