Remembering and Redressing the Forced Mobilization of Korean Laborers by Imperial Japan

Kim Hyo Soon and Kil Yun Hyung

Introduction by William Underwood

At a press conference in Seoul last week, Japanese Foreign Minister Okada Katsuya apologized for Japan’s harsh occupation of Korea from 1910-1945. “We should remember the agonies of people being ruled and never forget the feelings of victims,” Okada said. The agony currently being remembered most visibly concerns forced labor by Koreans in wartime Japan. Now led by the Democratic Party and seeking greater regional integration, the Japanese government is moving toward a conciliatory approach to this painful colonial legacy.

Such a shift was not immediately evident last December, when Japan’s Social Insurance Agency paid welfare pension refunds of 99 yen (about one dollar) to each of seven Korean women who had been deceived into working at a Nagoya aircraft factory for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in 1944-45. Then in their mid-teens, the women were never paid for their work but were told their wages were being deposited into savings accounts. The lawsuit they filed in Japan in 1998 eventually resulted in the refund of the pension deposits that were withheld—with no adjustment for six decades of interest and inflation.

Former forced laborer Yang Geum-deok, 81, cries during a rally in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul last December 24, after receiving her 99-yen payment from Japan. (AP via JoongAng Daily)

In a major breakthrough, however, Yonhap News Agency reported last month (based on an Asahi Shimbun article) that Japan soon will hand over to South Korea the payroll records for more than 200,000 Korean civilians coerced into working for private companies in Japan. Provision of the records will end the deep secrecy surrounding the 200 million yen (about two million dollars) that was earned by Korean workers but deposited by Japanese firms into the national treasury soon after the war. The South Korean state, which under the Basic Treaty of 1965 waived all rights to the funds held by Japan, needs this data to fully implement a 2007 law granting compensation of up to about $20,000 from its own coffers to forced labor victims and their families.

Roughly 700,000 Koreans were forced to work for private companies within Japan, while more than 300,000 Koreans were forced to serve in the Japanese military in fighting and support roles. In recent years Tokyo has cooperated to a limited extent in providing Seoul with information about military conscription and sending the remains of military conscripts to South Korea, but the latest move regarding civilian conscription is unprecedented. It is unclear if the Japan government now plans to play a more active role in returning the remains of civilian workers—or what it ultimately intends to do with the unpaid wage deposits that could be worth billions of dollars today.

Disclosure of the payroll records also is significant for normalization of relations between Japan and North Korea. Pyongyang’s demands for reparations for damages caused by colonialism, as opposed to the “economic cooperation” formula by which Japan restored ties with South Korea, appear to be strengthened by reports that a third of the records involve workers from northern Korea. (Japan is storing hundreds of sets of remains of military and civilian conscripts from the north, but in the absence of official relations there are no plans to return these.) Redress claims by non-Koreans that have languished due to the dearth of historical documentation may benefit indirectly. It turns out that, with sufficient political will, Japan can divulge sensitive records that have been locked away since the 1940s.

Reconciliation between Japan and Korea will continue to be a long, bumpy process. Ownership of the islets that Koreans call Dokdo and Japanese call Takeshima remains bitterly disputed. Dating back to 1992, there have been more than 900 weekly protest demonstrations in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, demanding greater sincerity in redressing the “comfort women” injustice. The systematic looting of Korean cultural properties during 35 years of Japanese rule has barely been discussed.

“Traces of Forced Mobilization,” a series now running in the Hankyoreh newspaper, encourages the two countries “to move together toward a brighter future after having resolved remaining issues concerning conscripted labor and other human rights issues.” Since its establishment in 1988, the Hankyoreh has been a distinctive voice in South Korea on matters of peace and democratization. The Hankyoreh has an online English version but, unlike larger Korean papers, no Japanese or Chinese versions. Reflecting the publication’s populist outlook and the dynamism of Korean-Japanese civil society, though, the Hankyoreh Fan Club translates key articles into Japanese and archives them online. (See Korean and Japanese descriptions of this volunteer translation project.)

Presented below, the first three parts of the “Traces of Forced Mobilization” series were written by reporters Kim Hyo Soon and Kil Yun Hyung. Part One deals with the legacy of labor conscription at Aso Mining. Although ousted as Japan’s prime minister last summer, Aso Taro remains a Diet member and Korean survivors of forced labor at his family’s firm plan to visit Japan, seeking apology and compensation, in June. Part Two describes redress efforts focusing on Mitsubishi’s former coal mines beneath islands in Nagasaki Bay. Part Three discusses hardships facing former labor conscripts on Sakhalin Island today. The package concludes with a column about the 2,601 sets of conscripted laborers’ remains still in Japan.

Korean newspapers ran New Year’s Day articles such as “1910-2010: A Century of Ascendence” and “Korea Looks to Elevate National Prestige.” Coming close on the heels of the annual crescendo of Japanese war memories, August 22 will mark the emotional centennial of Japan’s annexation of Korea. Political conditions will dictate whether the Japanese emperor accepts the presidential invitation to visit South Korea that has been extended. “This year will be a great turning point in Korea-Japan relations,” Foreign Minister Okada told his Korean hosts last week. The accuracy of this prediction will depend partly on progress regarding forced labor redress. –WU

Aso Group Denies Golf Course Sits atop Burial Grounds of Conscripted Korean Laborers

PART ONE – January 27, 2010 (English, Korean, Japanese)

The Japanese politically dynastic Aso family has failed to take responsibility for the 504 sets of human remains discovered in the Yoshikuma graves

Kim Hyo Soon

The Chikuho region, located right in the center of Fukuoka Prefecture on the Japanese island of Kyushu, reigned for decades as Japan’s top coal producer after mining development started in the late 19th century. Once its coal yield dropped in the 1960s and the Japanese government switched its basic energy source from coal to petroleum, the region’s economy contracted considerably. One storied mine after another shut down, and the miners, who were willing to take on mining work to eke out a bare livelihood, went off in search of other jobs.

Nowadays it is difficult to find any trace of the old mines in Chikuho. The top three mining centers here are Iizuka, Nogata and Tagawa. Currently, the only place where the pithead remains intact is the Hoshu mine site in Tagawa’s Kawasaki Village. This is because the government gave instructions that the pithead be filled up for safety reasons when the mine was shut down. The Hoshu Mine, where a residential area stands today, is a placer mine where the shafts descend obliquely. They go down a full kilometer, and it is said that it took a miner 30 minutes to walk down and another hour to come back up. After the mine was shut down in 1945, its coal exhausted, it stayed alive for rescue training purposes.

Korean map of the Chikuho region of Kyushu, Japan (Hankyoreh)

Yokogawa Teruo, the 70-year-old expert on forced labor issues who served as my guide on Jan. 19, took me inside the pithead so that I could sense a bit of the kind of working environment the miners faced. Yokogawa, who was a high school geography teacher before his retirement in 2001, is active in the Fukuoka Prefecture-based Truth-Seeking Network for Forced Mobilization. When we reached a spot that natural light could not reach, it became impossible to see anything in front of us. Yokogawa picked up a little stone and tossed it forward, and we heard a “plunk.” We could go no further, as it was not only pitch black but swamped in water as well.

There were no noticeable signs of the original look of Chikuho, save for a coal museum, the mine’s high chimneys, and the site of the winch that once rolled up the ropes, left alone by the local government for preservation purposes. Fewer still were traces of the forced mobilization that brought masses of Korean and Chinese laborers here to suffer human rights abuses until Japan’s defeat in World War II. Just after the defeat, the Japanese government and mining companies either obliterated or concealed the related data, and the old mining sites were mostly turned into apartment housing and parks. However, no matter how much the government and the companies that ran the mines feign innocence, there is no concealing the truth of history. The human remains that have emerged from the old mining sites, where beatings, abuse and accidental deaths once ran rampant amid poor working conditions, provide clear evidence as to how things were at the time.

The Aso Iizuka Golf Club, located in the Keisen village of Kaho-gun, Fukuoka Prefecture, is emblematic of the forces seeking to conceal the past. Located about 15 minutes by car from Iizuka Station, it was built on the old Yoshikuma Mine site, which was run by the Aso family. This site, where piles of the waste stone produced when coal is mined once stood, was refurbished and opened as a 27-hole golf course in October 1973. Its chairman is Representative Aso Taro, who was prime minister of Japan before stepping down last August after a defeat in the general election. A stone monument next to the course’s entrance bears the name of Suzuki Zenko, Aso’s father-in-law, who served as prime minister for over two years beginning in 1980. Aso’s maternal grandfather is Yoshida Shigeru, who laid the groundwork of conservative politics in Japan after the war. With three generations of prime ministers represented, no family with more prestige exists in the Japanese political world.

A few hundred meters from the entrance is an old supermarket. It was built on the location of the Yoshikuma mine’s bathhouse. It is said that there was a pithead nearby. A sign hanging there reads “Aso Yasaka,” perhaps a reflection of the Aso Group’s influence. The neighborhood’s administrative district is Yasaka, Keisen Village, Kaho-gun. Behind the supermarket is the Yasaka citizens’ center, with a children’s playground situated next to it. It is quiet and peaceful, with warm rays of winter sunshine falling over it. Shrouding this setting, which looks like something out of any other quiet country village, is a brutal history unsuited to its tranquil mood. Between December 1982 and January 1983, bulldozers were pulling up the ground here to build the new village citizens’ center when the remains of three people were found fully intact. The shocked villagers notified Aso, the owner of the land. Later it came to light that the site was a cemetery for people without surviving next of kin. Buried there were those among the people who died in or around the mine who had no family to collect their remains. The Japanese media paid little attention to the discovery.

A map of such burial sites for the dead of Yoshikuma Mine without surviving family, drafted by Aso Mining for internal use, was filled with records of where remains were located. It indicated there were no fewer than 504 sets of remains. Thirty-three had stone markers, twenty-one had wooden markers, and the remaining 450 had no markers at all. The map was never disclosed by Japanese media. It is now almost impossible to determine the identity of the remains, since any materials that might provide a clue are no longer extant. Nearly all of the Japanese who did physical labor in mines during the Japanese Empire were from the lower class. Second and third sons of poor farming villages without rice paddies to inherit went to work at the mines if they had no better means of survival. A number of them were burakumin, subject to discrimination from society. When people died, those who had no one to take their remains were simply buried in the ground. Even if there was an intention to cremate them, the high price of coal resulted in their effective abandonment.

A view of the front gate at the Aso-Iizuka Golf Club, of which former Japanese prime minister Taro Aso is chairman. (Kim Hyo Soon)

It is very likely that some of the remains from the Yoshikuma cemeteries are those of Koreans recruited or conscripted into labor during the Japanese Empire. The Yoshikuma mine was the largest of the seven mines run by Aso Mining in the Chikuho area. According to figures from January 1928, before forced mobilization began, there were 705 Koreans in total working at Aso Mining, with 162 at the Yoshikuma Mine. The figure increased rapidly as forced mobilization began in earnest.

On the evening of January 25, 1936, a fire broke out in the Yoshikuma mine shaft, taking the lives of 29 people. Twenty-five of them were Koreans. Some have attested that the company sealed up the entrance out of concerns that the fire might spread, even though it knew there were survivors in the shaft. The report on the tragedy in the January 27 edition of the Fukuoka Nichinichi Newspaper included the names of many Koreans among the deceased and severely injured. The article also includes a sentence that reads, “With a large number of Korean laborers in the shaft, the scene was chaotic, and at the pithead was the sad sight of Korean women who had rushed over out of concern for their fathers, husbands and brothers and collapsed from weeping.” There is a simple reason why the percentage of Korean victims was overwhelmingly high when an accident occurred in the mines. It is because Koreans were the ones mainly sent into the mines where large quantities of gas presented danger.

Today, an outsider would not have any idea at all about what was where in the Yoshikuma Mine site without guidance from an expert who has studied the problem of forced mobilization on the scene. After a long absence, Yoshikuma did show up in the Japanese news in December 2008. It was not because of Korean victims, but because of the sudden surfacing of a story about abuse against Allied POWs who had been brought here for forced labor during the Pacific War. Representatives from the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which was then the opposition party, asked then-Prime Minister Aso about the mobilization of 300 Allied POWs from Australia, Great Britain and the Netherlands to perform labor in a POW camp within the Yoshikuma Mine. Two of the Australian soldiers died at the mine. Aso, who was born in 1940, has dodged this issue whenever it has come up by saying that he was very young then and that he has no memories of it. However, he was ultimately forced to admit the existence of the Allied POWs when the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare acknowledged the belated discovery of related documents stored in its warehouse.

The Aso Group, however, maintains that it has nothing to do with the 504 sets of human remains discovered in the Yoshikuma graves. It simply says that the remains were collected during the redevelopment process and interred in a charnel house. Naturally, it does not acknowledge any responsibility. It is entirely unbecoming for a family line that has produced three generations of prime ministers.

Remains of Unidentified Korean Conscripted Laborers Remain at Takashima Island

PART TWO – February 3, 2010 (English, Korean, Japanese)

Observers say it would be possible to identify the remains if the Japanese government demands the temples examine related documents such as death registries

Kim Hyo Soon

“Takashima, Hashima, Sakito.”

These three words were on the lips of miners and people of the Nagasaki Prefecture mining industry during the period of the Japanese Empire. Today, there is a bridge leading to Sakito and it can be reached from central Nagasaki by traveling about two hours on the expressway, but at that time all three islands were cut off completely from the outside world by rough waves. Minors called them the “Ghost Islands,” meaning that anyone who set foot on them was unlike to come back alive. Even the most experienced ones who had worked in the coalmines of the Chikuho area, the site of the largest coalfield on Kyushu, were afraid to go to the Ghost Islands. The order of the sites was determined by the rhythm of Japanese pronunciation, but in terms of poor working environments, they are all said to have been more or less the same.

Chief among the things the three islands had in common was the presence of large-scale submarine coalmines. Miners are said to have traveled down to depths of up to 900 meters off Hashima for underwater mining.

A second commonality was the fact that Mitsubishi Corporation was in charge of managing operations for all three island mining sites. Since the exploration of underwater mines required the most up-to-date mining technology and was tremendously expensive, the project was taken over from small to mid-sized mining companies by Mitsubishi, which had gone from triumph to triumph after becoming in league with the government following the Meiji Restoration.

Mitsubishi, meaning “three diamonds,” profited from massive use of forced labor but has never compensated victims.

The third thing the islands shared was a considerable presence of Koreans, who were forced to endure the hardship of mining on faraway islands through recruitment and conscription. Among them were the victims of so-called “double conscription,” who were forced to work in the mines of Sakhalin during the Japanese Empire and then came to the Ghost Islands late in the war.

On Jan. 22, I took a high-speed passenger ferry from Nagaski Terminal to Takashima, located about 14.5 kilometers away. When I arrived at the Takashima pier after a trip that lasted about 35 minutes, I saw a sign indicating that this was a tourist site. A large statue stood about 20 meters away from the ferry’s anchorage. The statue, erected in December 2004, was an image of Iwasaki Yataro (1835-1885), founder of Mitsubishi Corporation. Mitsubishi took over the Takashima mine in March 1881. It went on to run the mine until it was closed in November 1986, which means that it maintained its influence as a big player on this island for no less than 105 years.

Located right at the center of the island is the mountain Gongen-zan, which rises 120 meters above sea level. About halfway up the mountain is a shrine, and beside it lies a flat plot of land with a memorial marker in one corner. That marker was erected by Mitsubishi Coal Mining Company two years after the mine closed down. On the upper right of the marker is a flower relief with scratches around it. Takazane Yasunori, the 71-year-old director of the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum who accompanied me, told me that there was originally an inscription where the relief is currently, but that someone with a grudge destroyed it with a sledgehammer. He said that after repairing the parts that had fallen away, the company covered up the remains of the inscription with a relief.

Mitsubishi Coal Mining Company erected a memorial honoring miners beside Takashima Shrine in 1988. A controversial inscription about Japanese, Korean and Chinese miners “sharing joy and sorrow together” was destroyed and later replaced by the flower relief. (Kim Hyo Soon)

What could have been written in the inscription that would cause someone to act in such a hostile manner bearing a grudge? The original text consisted of two paragraphs. The first said that those honored had made great contributions to the development of the Japanese economy and the promotion of the local community, but that they were unable to deal with the flow of the times and had lowered the curtain on a glittering history lasting over a century. It is the second paragraph that clearly shows Mitsubishi’s understanding of conscripted labor. The somewhat lengthy paragraph reads as follows.

“We long for the days in which many workers and their families, including people who came from China and the Korean Peninsula, transcended race and nationality to share one heart in tending the flame of coal mining and sharing joy and sorrow together, and we pray for the eternal rest of those who lost their lives during their work or perished on this land by erecting this monument to comfort all their souls.”

When the contents of the inscription became known, ethnic Koreans who had endured harsh treatment at the site during the Japanese Empire were unable to conceal their anger. There was nothing written to indicate that Korean and Chinese workers had been brought there against their will. The people who were brought to the Ghost Islands endured harsh labor, beatings, and punishments, and a number of them died in accidents or from malnutrition. Japanese civic groups protested, charging that expressions such as “sharing joy and sorrow” flew in the face of historical fact, but the company refused to modify the inscription, claiming that it had already passed through prior discussions with the local headquarters of the Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan) and the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon). It was in the midst of this controversy that the destruction of the inscription took place.

Staff members of the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum clean the “Senninzuka” memorial tower, which originally contained an ossuary underneath. (Kim Hyo Soon)

Another ten minutes of walking from the shrine takes you to the Takashima Cemetery. This is a public cemetery for residents of the island. Perhaps because this is one of the areas in Japan where the Christian faith took root the fastest, one can see quite a number of headstones engraved with the baptismal names of the deceased. As you head inward, the cemetery ends and bushes appear before you. If you follow the faint trail between the bushes, you can find a very old stone monument, with a marker explaining that it is a memorial tower. It has no official name, but locals call the site “Senninzuka,” which translates as “thousand-person tomb.” It is said that the monument originally had an ossuary underneath, which contained the remains of countless people who came to work at the mines and ended up dying in a foreign land. These included the remains of Koreans who were conscripted to perform labor during the Japanese Empire and died while toiling on the islands of Takashima and Hashima. A program made in the mid-1970s by NBC, Nagasaki’s local broadcasting network, contains an image showing a Korean name on one of the boxes of remains interred at Senninzuka.

However, something astonishing happened when Mitsubishi moved the Senninzuka remains to a nearby temple during the closure of the Takashima Mine, claiming that it was laying them to eternal rest. The company moved the ashes into cup-sized jars and interred them in Kinshoji, a temple near the cemetery, then sealed up the ossuary that had been underground. Around 115 such jars were moved to the temple from Senninzuka at the time. About ten of them had Japanese names written on them, while the remainder had nothing. Under the circumstances, it is very likely that the unknown remains belonged to Korean victims, but at present it is difficult to confirm in any way. For around a decade, the Association of Family Members of Korean Victims at Hashima and Japanese civic groups have been calling on Mitsubishi Materials Corporation, the successor to Mitsubishi Coal Mining, to dig up the sealed ossuary, but the company has stubbornly refused to do so, claiming that it “might harm the dignity of their souls.”

Museum Director Takazane Yasunori called this “incredibly wicked and craven.” While he had maintained a gentle expression during his words up until that point, his tone became coarse as he talked about Mitsubishi‘s attitude. It would be possible to identify the remains, he said, if the Japanese government demanded with sincerity that the temples involved examine related documents such as death registries.

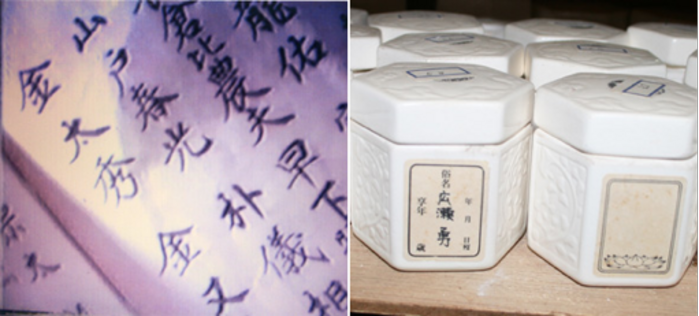

Korean names that were on urns in the “Senninzuka” ossuary (left) were replaced by numbers when the urns were transferred to Kinshoji temple (right). (Hankyoreh)

There are still no precise figures on the number of deaths among Koreans taken to the three Ghost Islands. Japanese researchers estimate that around 6,000 conscripts were taken to Sakito, and 4,000 to Takashima and Hashima. According to an investigation based on reports by surviving family members, the South Korean government’s Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Imperialism puts the number of those who died on the islands at 59. However, it is likely that the number of actual victims is far greater.

Korean Former Conscripted Laborers Live Out Last Days on Russia’s Sakhalin Island

PART THREE – February 10, 2010 (English, Korean, Japanese)

Koreans conscripted for labor in coal mines by Japan were unable to return to Korea following Liberation in 1945 as a result of ignorant policy decisions by the South Korean and Japanese governments

Kil Yun Hyung

“So, I have ended up with three names.”

Cho Yeong-jae, 78, spoke with a respectable Gyeongsang Province dialect. Our meeting took place in Boshnyakovo (called “Nishisakutan” in Japanese), at a mining village where I arrived after a six-hour car ride northwest from Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, the largest city on Russia’s Sakhalin Island. The birch forests that surrounded the village had turned white from a few days of snowfall, and Boshnyakovo’s small harbor, facing the maritime province of Siberia, is said to still be frequented by Korean and Japanese boats bearing coal for burning at thermal power plants.

Cho was born in 1932 in Pungsan, a township in the county (now city) of Andong in North Gyeongsang Province. In 1942, he came to Sakhalin following his father, who had been conscripted into labor service as a coal miner. When he enrolled in the island’s Japanese school, the young man’s name became “Matsumoto Eisai,” and when Japan lost to the Soviet Union in 1945 and the entire island became Soviet territory, his name was changed once again, this time to “Yuri Cho.” Nearly 70 years have passed since then, but Cho has been unable to leave Sakhalin behind.

“When I came here in 1942, Koreans were packed into three hambajip (worker dormitories). Over here, they were mostly from Gyeongsang Province, and down at Shakhtersk they were mainly from North Korea. There were a lot of people at Kitakozawa (Telnovskiy), from Chungcheong Province and Jeolla Province. The coal is good here. If the Koreans did not follow orders, they were taken off to the takobeya (a detention facility for mine workers), and whenever someone went in there, he returned not right in the head.”

During the period of the Japanese Empire, Sakhalin was called Karafuto, which in the Ainu language means “island of birches.” Half of the island, the portion south of 50 degrees north latitude, was ceded by Russia to Japan after Japan’s victory in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. Japan subsequently went to work exploiting the island’s rich natural resources. It made up for the lack of workers by bringing people in from Japan and Korea. It has been confirmed that 7,801 Koreans (6,120 of them miners) worked at 25 of the 26 mines operated in southern Sakhalin as of late July 1944.

Kim Yun-deok and Kim Mal-sun at their home in Sinegorsk in central southern Sakhalin, Russia. (Kil Yun Hyung)

Eighty-seven-year-old Kim Yun-deok, whom I met in the town of Sinegorsk in central southern Sakhalin, hails from Gyeongsan City in North Gyeongsang Province. After arriving on the island in 1943 in place of his father, he worked for around two years as a miner. An estimated 43,000 Koreans were living in southern Sakhalin, including Kim, just after Liberation in August 1945. A majority of them came from what would become known as South Korea after Liberation.

For Kim, Liberation was an “indefinite leave” that came one day out of the blue. “I headed to work one day and they said I didn’t have to work. Japan had lost, they said,” he recalled. After Liberation, Sakhalin was in pandemonium with a mixture of Soviet troops who had come south and Japanese and Koreans trying to evacuate to the mainland. The Japanese, agitated with the shock of defeat and fear of the Soviet forces, carried out massacres of Koreans at sites like the southwest Sakhalin towns of Porzaskoye (Mizuho in Japanese) and Leonidov (Kamishisuka). “We had been liberated, but they said those Japanese dumped the Koreans at Homsk (a port city in southwest Sakhalin) and went by themselves. They even say they killed the Koreans who were on board. If the Soviet forces had come just a bit later, all of the Koreans would have been dead.”

Even after the post-Liberation chaos ended, Kim was unable to return to his homeland. Through a project to repatriate Japanese from South Sakhalin beginning in December 1946, some 292,590 Japanese headed home, but the Koreans on the island were excluded as “no longer Japanese.” Kim ultimately obtained Soviet citizenship and spent another 37 years as a miner before retiring in 1982.

I met 76-year-old Ahn Bok-sun in the mining city of Uglegorsk in northeast Sakhalin. Hailing from Ulsan, she came to Sakhalin in 1942, following her father Ahn Cha-mun (1902-1980). While working at the Kitakozawa (Zelnovskiy) Mine in the northeast part of the island, he was subjected to “double conscription” in August 1944 and sent to the Japanese island of Kyushu. When the war ended, he stowed away on a boat in Hokkaido and arrived home [in Sakhalin] after a journey of hardship, but he suffered from lingering health problems and was unable to do much work. Ahn said that her father walked over 400 kilometers from the southern port of Korshakov to find his wife and children.

She recalls him telling her, “It was terrible. The Nagaski mines have you digging coal underwater. They beat us with leather straps while we were working.” In 1998, Ahn’s husband went to the bank to convert a large amount of currency ahead of a visit to his hometown in South Korea. The South Korean government has allowed Koreans in Sakhalin to visit their hometowns since 1989, thus her husband had been preparing to participate in the first hometown visit. He was followed home and killed by members of the Russian mafia.

Hashima, also known as Battleship Island, was one of three islands in Nagasaki Bay where Mitsubishi forced Korean and Chinese workers to extract coal from undersea mines.

However, the homeland that he was never able to visit viewed the family and other Korean conscripted laborers of Sakhalin as a “potential threat to security.”

According to data from the Busan Metropolitan Police Agency’s security division unearthed by the Hankyoreh at the National Archives of Korea, in 1990 the South Korean government had detectives from that division monitor the activity of Koreans living in Sakhalin who were visiting their hometowns in Korea at that time 24 hours a day. Ahn said, “Now I have no husband, and I do not want to go back to Korea and leave my children alone.”

On Jan. 26, the Second Public Cemetery in the back hills of Boshnyakovo was buried in drifts of white snow. There I visited the grave of Choi Wol-ju (1905-1986), the grandmother of 58-year-old Choi Jong-guk, head of the Korean residents’ association in Uglegorsk. (Some Koreans in Sakhalin have adopted the Russian practice of wives taking their husband’s surnames.) All around were the graves of Koreans who had died on the island.

Cho Yeong-jae’s home lies five minutes by car from the back hills where the graves are located. Hanging on the wall there is a 2007 calendar from home, which he picked up when visiting Seoul for the Lunar New Year’s and Chuseok holidays. Cho said, “Now that I have lived in Russia for more than 60 years, I am more used to the name Yuri than the name Yeong-jae.”

“My wife is sick and I cannot stop thinking about my children. I want to go home, but I cannot,” he added. Although the South Korean government has allowed the Korean former conscripted laborers in Sakhalin to permanently return home since 1992, the government does not allow their children to return permanently. As a result, this had led to criticism that the policy concerning Korean former conscripted laborers living in Sakhalin could result in another case of Korean family dispersal.

Will he also be buried in the mountain cemetery when he dies? As I left, he clasped my hand and repeatedly thanked me for visiting.

Returning Conscripted Laborers’ Remains in Japan to South Korea

COLUMN – January 20, 2010

Kim Hyo Soon

It was reported last week that the remains of 2,601 Koreans who died while performing conscripted labor during the Japanese occupation are currently in Japan. The South Korean government’s Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Imperialism said that this figure, calculated between mid-2005 and late 2009, does not include some remains that were mixed together, so the number of remains that have never returned home is likely much higher.

Every time I see one of these reports, it is difficult to stop part of me from flaring up in rage. No longer can we use the common excuse that our division into North Korea and South Korea and our competition with one another has left us with no room to worry about small things like human remains.

The first person to systematically analyze the heartbreaking lives of Koreans drafted into forced labor in Japanese society was Park Gyeong-sik, a former instructor of Korea University in Tokyo. Park, who in 1965 released “Records on the Forced Mobilization of Koreans,” said that a great impetus was the collection of remains by the Chinese government of Chinese forced laborers who died in wartime Japan.

Li Dequan, who came to Japan in the 1950s as chair of the Red Cross Society of China and contributed to recovering the remains of Chinese victims, was born a minister’s daughter and married Feng Yuxiang, a Chinese warlord. She would later serve as Minister of Health after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. Her visit to Japan was recorded as the first by a Chinese government official since the communist administration was established on the mainland. The road leading up to the visit was full of twists and turns, as it was a time when the U.S. recognized the Kuomintang government of Chiang Kai-shek, chased off to the island of Taiwan, as the only legal Chinese government and was adopting a policy of containment against mainland China. There are a number of implications for us in Li’s process of collecting the Chinese remains, at a time when the issue of unrepatriated remains still weighs heavily upon us.

Three factors played a part in resolving the remains issue in the absence of diplomatic relations between Japan and China. The first was self-reflection within the Japanese Buddhist community, which had openly cooperated with the policies of the imperial government during the war. Toward the end of World War II around 40,000 Chinese laborers were forcibly taken from China and sent to work at 135 sites throughout Japan, where they endured harsh treatment. It is estimated that some 7,000 of them died. Some Japanese Buddhists and progressives viewed the return of their remains as a point of departure for new relations with China, and they joined forces to establish the Memorial Committee for Martyred Chinese Captives.

The second factor was the flexible diplomacy of the government in Beijing, which made appropriate use of the remaining Japanese resident population in China and the Japanese war crimes card. In late December 1952, China delivered a radio announcement on its study of the remaining Japanese population and said that the Chinese government intended to cooperate and help the remaining Japanese population wishing to return to their home country. The Japanese Red Cross Society, Japan-China Friendship Association and Peace Liaison Committee then sent delegations to Beijing for negotiations. Even at a time when the U.S. and China were engaged in a full-on clash during the Korean War, passenger boats traveled back and forth between Japan and China, filled with Japanese returning home. Returning home to China at the same time were the remains of around 5,000 Chinese victims. The Chinese accepted these remains not as those of prisoners-of-war but as “martyrs in the anti-Japanese struggle.”

The third factor was the political world, which viewed expanded trade and economic exchange with mainland China as essential for Japan’s economic revival. Buddhists and the Memorial Committee for Martyred Chinese Captives invited a delegation from the Chinese Red Cross Society to Japan as a gesture of gratitude to China for repatriating the remaining Japanese residents, but the Cabinet under then-Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru balked at giving its approval. The delegation finally arrived at Haneda Airport in late October 1954, after a resolution for the invitation was adopted by the Diet.

Police confiscate a mask of the Japanese emperor during a February 7 demonstration in Seoul. Many Koreans say that any visit to South Korea by the emperor must be preceded by an imperial apology for Japan’s colonial rule. (Kim Bong-kyu / Hankyoreh)

It is very unfortunate that the Buddhists and progressives in Japan at the time did not focus very much on the repatriation of Korean remains. However, before the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Imperialism was launched in 2004, there was essentially no organization in the South Korean government exclusively handling the issue of Korean remains.

The commission will be forced to shut down soon unless separate legislative measures are taken. When will there ever be signs of resolution in the drawn-out process of reclaiming these Korean remains?

[The views presented in this column are the writer’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those of The Hankyoreh.]

Kim Hyo Soon and Kil Yun Hyung are reporters at the Hankyoreh, where the above four articles appeared on January 27, February 3, February 10 and January 20, 2010.

Posted at The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus on February 15, 2010.

Recommended citation: Kim Hyo Soon and Kil Yun Hyung, “Remembering and Redressing the Forced Mobilization of Korean Laborers by Imperial Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 7-3-10, February 15, 2010.

See also:

William Underwood, New Era for Japan-Korea History Issues: Forced Labor Redress Efforts Begin to Bear Fruit

William Underwood, “Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages: Reparations for Korean Forced Labor in Japan” Part 1 & Part 2

Lukasz Zablonski and Philip Seaton, The Hokkaido Summit as a Springboard for Grassroots Initiatives: The “Peace, Reconciliation and Civil Society” Symposium