Walden Bello

Ten years after the Asian financial cataclysm of 1997, the economies of the Western Pacific Rim are growing, though not at the rates they enjoyed before the crisis. The region has been indelibly scarred by the crisis. There is greater poverty, inequality, and social destabilization than before the crisis. South Korea’s painful labor market reforms, for instance, have produced the quiet desperation behind one of the highest suicide rates among developed countries.

Meanwhile, despite all the talk about a “new global financial architecture,” there is little in place to regulate the massive amounts of capital shooting through global financial networks at cyberspeed – one of the chief causes of the 1997 crisis. Leave-it-to-the-market enthusiasts tell us not to worry and confidently point out that there’s been no major crisis since the Argentine bankruptcy in 2002.

But those who know better, like Wall Street insider and former treasury secretary Robert Rubin, are very worried even as they resist regulation. “Future financial crises are almost surely inevitable and could be even more severe. The markets are getting bigger, information is moving faster, flows are larger, and trade and capital markets have continued to integrate,” Rubin writes in his book In an Uncertain World. ”It’s also important to point out that no one can predict in what area—real estate, emerging markets, or whatever else—the next crisis will occur.” A recent study by the Brookings Institution confirms Rubin’s fears: there have been over 100 financial crises over the last 30 years.

The Reign of Finance Capital

The amount of speculative capital sloshing around in global financial circuits is truly mind-boggling. According to McKinsey Global Institute figures cited by Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf, the global stock of “core financial assets” stood at $140 trillion in 2005. Traditional commercial banks held a significant amount of global financial assets. But non-bank financial operators, which have become important intermediaries between savers and investors, accounted for $46 trillion in 2005, hedge funds for $1.6 trillion, and private equity investors about $600 billion. These figures and other data on the stupefying rise and scale of global finance capital were presented by economist C.P. Chandrasekhar at the conference “A Decade After: Recovery and Adjustment since the East Asian Crisis” held in Bangkok, the epicenter of the 1997 financial earthquake, in mid-July.

The explosive growth of finance capital stems from the overcapacity plaguing the global economy. This has resulted in a marked slowdown in investment in major parts of the global economy, with notable exceptions like China and the United States. With the global economy stagnant, capitalists are less motivated to invest in more productive capacity and have more incentive to move their money to speculative activity and to squeeze more value out of already created value.

Speculative activity as a mode of profit-making has also outrun trade, with the daily volume of foreign exchange transactions in international markets standing at $1.9 trillion daily, compared to an annual value of $9.1 trillion of trade in goods and services. In other words, speculative activity in a single day amounted to 20% of the annual value of global trade! Martin Wolf, one of the cheerleaders of globalization, captures today’s power relations among the fractions of global capital when he writes: “The new financial capitalism represents the triumph of the trader in assets over the long-term producer.”

Ten years after the IMF and the United States put the blame for the crisis on the alleged non-transparency of financial transactions in Asian countries, opaqueness is now the order of the day when it comes to global finance. The movements and mutations of speculative capital have outstripped the capacity of national and multilateral regulatory authorities. In addition to traditional credit, stocks, and bonds, new and esoteric financial instruments such as derivatives have exploded on the financial scene. Derivatives represent the financialization — the buying or selling of risk — of an underlying asset without trading the asset itself. Today, risk on everything can be financialized and traded, from the pace of carbon trading to the rate of Internet broadband connections to weather predictions.

Paralleling the emergence of more complex instruments has been the rise of hedge funds and private equity funds as the most dynamic players in the global casino. Hedge funds, said to be key villains in the Asian financial crisis, are now even more freewheeling. Numbering over 9,500, hedge funds take short and long positions on a variety of investments, with a view to minimizing overall risk and maximizing profits. Private equity funds target firms in order to control, restructure, then sell them for a profit.

Reserve Accumulation Strategy

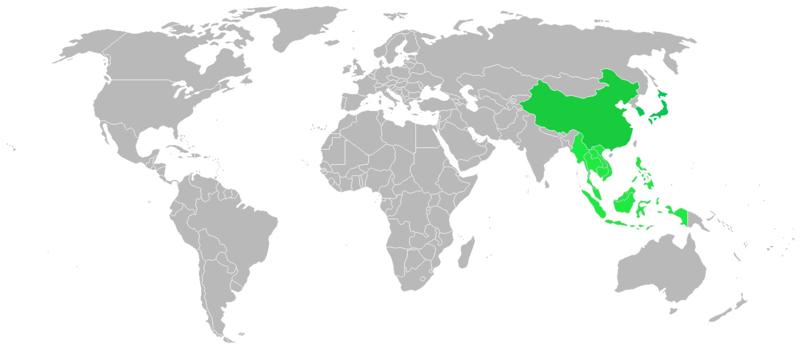

With the absence of global financial regulation to tame the whirlwind of global finance, Asian countries have taken measures to defend themselves from the volatile global speculators that brought down their economies when in panic they pulled $100 billion out of the region. To protect their economies, the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) have banded together with China, South Korea, and Japan to form the “ASEAN Plus Three” financial grouping. This arrangement enables member countries to swap reserves if speculators again target their currencies.

Even more important, these countries have built up financial reserves by running massive trade surpluses, an objective they have achieved by keeping their currencies undervalued. Between 2001 and 2005, according to Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, eight East Asian countries — Japan, China, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines — more than doubled their total reserves, from roughly $1 trillion to $2.3 trillion. China, the leader of the pack, is estimated to now have over $900 billion in reserves, followed by Japan.

This has resulted in a highly paradoxical situation. In a global economy marked by strong tendencies toward stagnation, China as producer and the United States as consumer are the twin engines that keep the world economy afloat. Yet to keep its economy going, the United States needs a constant flow of credit from China and the other East Asian countries to finance the middle class consumption of goods produced…in China and Asia. In the meantime, countries like those in Africa that really need the capital from East Asia get very little of these reserves since they are not considered creditworthy.

The Demise of the IMF

Asian countries have built up large reserves because of their bitter experience with the International Monetary Fund. Governments recall the crisis as a one-two-three punch delivered by the IMF. First, the Fund, along with the U.S. Treasury Department, pushed them to liberalize their capital accounts, which resulted in the easy exit of foreign capital that brought down their currencies. Then, the IMF provided them with multibillion dollar loans, not to rescue their economies but to rescue foreign creditors. Then, as their economies wobbled, the Fund told them to adopt pro-cyclical expenditure-cutting policies that accelerated their plunge into deep recession.

“Never again” became the slogan of a number of the affected governments. The Thaksin government in Thailand declared its “financial independence” from the IMF after paying off its debts in 2003, vowing never to return to the Fund. Indonesia has said it will pay off all its debts to the IMF by 2008. The Philippines has refrained from contracting new loans from the Fund, while Malaysia defied it by imposing capital controls at the height of the crisis.

Ironically, then, the IMF has become one of the key victims of the 1997 debacle. This arrogant institution of some 1,000 elite economists never recovered from the severe crisis of legitimacy and credibility that overtook it — a crisis that was deepened by the bankruptcy of its star pupil Argentina in 2002. In 2006, Brazil and Argentina, following Thailand’s example, paid off all their debts to the Fund in order to achieve financial independence. Then Hugo Chavez let the other shoe drop by announcing that Venezuela would leave the IMF and the World Bank. This boycott by its biggest borrowers has translated into a budget crisis for the IMF.

This succession of events has left the IMF with scarcely any influence among the big developing countries. But the unraveling of the authority and power of the IMF is due not only to the resistance to further Fund intervention by developing countries. The Bush administration itself contributed to eroding the Fund’s search for a meaningful role in global finance when it vetoed a move by the conservative American deputy director of the Fund, Ann Krueger, to create an IMF-supervised “Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism” (SDRM) that would have allowed developing countries a standstill in their debt repayments while negotiating new terms with their creditors. Although many developing countries regarded the proposed SDRM as weak, Washington’s veto showed that the Bush people were not going to tolerate even the slightest controls on the international operations of U.S. finance institutions.

Neoliberalism Rejected: Thailand

It is not only the IMF but neoliberalism, the dominant ideology of the 1990s, that came crashing down in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis. Malaysia imposed capital controls and stabilized the economy, allowing it to weather the recession in 1998-2000 better than other afflicted countries. It was, however, Thailand that most dramatically broke with neoliberalism. After three stagnant years under governments faithfully complying with the IMF’s neoliberal prescriptions, the newly elected government of Thaksin Shinawatra propelled countercyclical, demand-stimulating neo-Keynesian policies to get the economy back on track. The Thai government froze repayments on rural debt, instituted government-financed universal health care, and gave each village one million baht to spend on a special project. Despite dire predictions from neoliberal economists, these measures contributed to propelling the economy onto a moderate growth path that has since been sustained by demand created by China’s red-hot economy.

The 1997 financial crisis, which saw one million Thais drop below the poverty line in a few short weeks, turned the populace against neoliberal globalization. Even as the government refocused on stimulating domestic demand through income support for the lower classes in the countryside and the city, popular sentiment went against free trade. On Jan 8, 2006, several thousand Thais tried to storm the building in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where negotiations for an FTA (free trade agreement) were taking place between the United States and Thailand. The negotiations were frozen; indeed, Prime Minister Thaksin’s advocacy of the FTA became one of the factors that contributed to his loss of legitimacy and eventually his ouster from power in September 2006.

This souring on globalization has been paralleled by the rise in popularity of the economic program of the country’s popular monarch, King Bhumibol. Dubbed the “sufficiency economy,” it is an inward-looking strategy that stresses self-reliance at the grassroots and the creation of stronger ties among domestic economic networks. Taking advantage of the King’s popularity, critics claim that the military-supported government that overthrew Thaksin is cleverly using the sufficiency economy to legitimize its rule. Whatever the case, globalization is an unpopular word in Thailand today.

Neoliberalism Imposed: Korea

While Thailand broke with neoliberalism and the IMF, South Korea followed almost to a “t” the neoliberal reforms forced on the government by the Fund. It undertook radical labor market restructuring, trade liberalization, and investment liberalization. According to sociologist Chang Kyung Sup, “labor shedding was the most crucial measure for rescuing South Korean firms. Even after the breathtaking moments were over, most of the major firms continued to undertake organizational and technological restructuring in an employment minimizing manner, and thereby got reborn as globally competitive exporters.”

Once the classic activist developmental state, which a report of the U.S. Trade Representative characterized as the “most difficult place in the world” for U.S. enterprises to do business in, Korea under IMF management has become a much more liberal economy than Japan. Denationalization of Korea’s financial and industrial firms has taken place with “appalling speed,” says Chang, with foreign ownership now accounting for over 40% of the shares of Korea’s top financial and industrial conglomerates or chaebol. Samsung now has 47% foreign ownership, the steel company Posco over 50%, Hyundai Motors 42%, and LG Electronics 35%.

The IMF has touted Korea as a “success story.” However, Koreans hate the Fund and point to the high social costs of the so-called success. According to South Korean government figures, the proportion of the population living below the “minimum livelihood income” — a measure of the poverty rate — rose from 3.1 per cent in 1996 to 8.2 per cent in 2000 to 11.6 per cent in early 2006. The Gini coefficient that measures inequality jumped from 0.27 to 0.34. Social solidarity is unraveling, with emigration, family desertion, and divorce rising alarmingly, along with the skyrocketing suicide rate. “We have one big unhappy society that looks back to the pre-crisis period as the golden age,” says Chang.

All Fall Down

Although the Asian financial crisis of 1997 may have brought about the downfall of the IMF, economist Jayati Ghosh points out that it also marked the demise of the East Asian developmental state. This developmental state had aggressively managed the integration of the national economy into the world economy so that it would be strengthened, not marginalized by global economic forces.

Despite their different pathways from the crisis, the economies of East Asia have been irrevocably scarred and weakened. The crisis marked the end of their being at the forefront of development, as models to be emulated. The 21st century that was supposed to be their century slipped away. The cataclysm marked the passing of the torch to China. In their weakened state, the smaller East and Southeast Asian economies have now become increasingly dependent on the dynamism imparted by their giant neighbor.

Walden Bello is a professor of sociology at the University of the Philippines at Diliman, a senior analyst at the Bangkok-based research and advocacy institute Focus on the Global South, and a columnist for Foreign Policy In Focus. He is the author of Deglobalization: Ideas for a New World Economy.

This article appeared at Foreign Policy in Focus on July 30, 2007. Posted at Japan Focus on August 1, 2007.

For further analysis of the 1997 Asian financial crisis see Chris Giles and R. Taggart Murphy, The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 a Decade On: Two Perspectives.