‘The Law of next year’ in Japanese politics

By Wakamiya Yoshibumi

[The chief of the Asahi shimbun’s editorial board here draws attention to

the cycle of reconciliation/repudiation, apology/assertion in Japan’s

attitudes towards Asia. He dubs this the “Law of Next Year,” meaning that

the one is inevitably followed by the other.

Wakamiya’s brief survey through the administrations of Sato and Fukuda in

the 1970s, Nakasone in the 1980s, Obuchi in the 1990s and Koizumi in the

2000s is instructive, but it raises more questions than it answers.

For one thing, the “apologies” scarcely deserve to be known by that term.

The carefully calibrated expressions of regret have repeatedly failed the

basic test of sincerity not only because they are bureaucratic formulations

intended to deny responsibility as much as concede it, but because they

lack the natural accompaniment of apology – restitution, for example

payment to victims of atrocities and human rights violations.

For another, the sequence that might once have followed something like a

one year rule seems now to follow a much more rapid cycle. It was on the

very day (22 April 2005) that Prime Minister Koizumi issued a war apology

in Jakarta to try to dampen the anti-Japanese movement then spreading

throughout the region that 80 Diet members, most of them from his own

party, joined in making their ceremonial visit to Yasukuni shrine. Apology

and assertion may occur on the very same day.

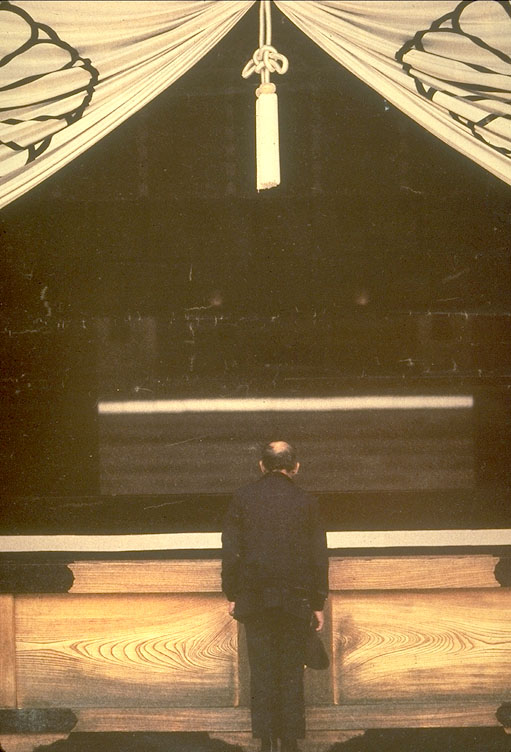

Former Prime Minister Fukuda

visiting Yasukuni Shrine

Koizumi’s persistence in making annual Yasukuni visits, spurning protests

from Beijing and Seoul as attempts to “meddle in spiritual matters and

turn them into diplomatic issues,” and the various moves to enforce

patriotism and remove constitutional restrictions on the possession and

use of military force, deeply disturb Japan’s neighbors.

Wakamiya suggests he is dealing with something akin to “acrobatic stunts”

on the part of the LDP, but surely it is rather more than that. Is he not

in fact pointing to symptoms of a deep-seated and steadily worsening

national schizophrenia? (GMcC)]

Team Japan under the leadership of Oh Sadaharu had just scored a dramatic victory in the inaugural World Baseball Classic (WBC) championships, which greatly tickled Japanese pride. In particular, the three games between Japan and South Korea produced a lot of sparks. I also passionately rooted for Japan in front of the television.

There is little harm in displaying nationalism over such events, I thought, as I recalled how an anti-Japanese movement flared in South Korea a year ago over the enactment of the “Takeshima Day” ordinance by Shimane Prefecture. The Takeshima islands, called Tokto in South Korea, comprise two rocky outcrops in the Sea of Japan. The two countries dispute ownership of the territory.

Emperor’s apology

While WBC players were developing an intense battle on the baseball field, Japan and South Korea were locked in a bizarre diplomatic tussle.

First, Park Geun Hye, head of the opposition Hannara Party, visited Japan and met with Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro. The meeting took place at a time when summit meetings between Japanese and South Korean leaders were on ice. South Korean President Roh Moo Hyun refused to visit Japan in protest over the prime minister’s visits to war-related Yasukuni Shrine. Needless to say, Koizumi welcomed Park to Japan with open arms.

In mid-March, meantime, former Chief Cabinet Secretary Fukuda Yasuo visited Roh at his presidential office in the Blue House together with former Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro as part of an exchange program organized by the Japan-South Korea cooperation committee. Fukuda made a strong impression by showing his determination to make “a revolutionary advancement” in Japan-South Korea relations.

However, Roh countered the Japanese delegation by throwing a close breaking pitch, saying, “If possible, I wish to visit Yushukan,” referring to the museum that stands on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine. Both visiting and receiving Japanese and South Korean officials are engaged in a psychological war in which foreign and domestic situations are intricately entangled.

When Nakasone visited the Blue House, he must have been reminded of his 1983 visit to South Korea. In January of that year as prime minister, Nakasone chose South Korea as the destination of his first foreign trip and met with then President Chun Doo Hwan with whom he developed a rapport. Up until then, bilateral relations had been shaky mainly due to the textbook issue and other problems. But suddenly, relations dramatically improved.

In the fall of 1984, Nakasone invited the president to Japan and arranged for him to meet with Emperor Hirohito, posthumously known as Emperor Showa. The landmark event materialized as an extension of the previous year’s summit meeting. The emperor’s words, “It is very regrettable that an unfortunate past existed between our countries” amounted to an apology by the emperor.

There is no doubt that Nakasone played a leading role in the process that led to Japan-South Korea reconciliation.

At the same time, however, Nakasone must also have been reminded of a bitter event in the past when Roh made reference to Yasukuni Shrine. On Aug. 15, 1985, Nakasone officially visited the shrine to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the end of World War II. His visit triggered a furious reaction from China and since then, he has stopped visiting the shrine.

Be that as it may, I still vividly recall how he pompously paraded through the premises of the shrine with his entourage of Cabinet ministers behind him. His bearing had the unmistakable look of a nationalist as he proudly led the procession.

Acrobatic stunts

The year after he took the lead in achieving a historical reconciliation with South Korea, the prime minister demonstrated revivalistic nationalism. It shows there are two conflicting sides to Nakasone’s personality. But a look at postwar Japanese politics tells us the trend is by no means unique to Nakasone’s administration.

For example, in 1965 Japan finally settled outstanding issues stemming from its colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula when it concluded the Japan-South Korea Basic Treaty. The difficult negotiations had finally reached a conclusion thanks to the following statement by Shiina Etsusaburo, who served as foreign minister in the Cabinet of Sato Eisaku, during his South Korean visit: “We feel great regret and deep remorse over the unhappy phase in the long history of relations between the two countries.” This statement has become the prototype of Japan’s subsequent apologies to Asia.

A year later, in 1966, the same Sato administration designated Feb. 11 as National Foundation Day to be observed as a national holiday. The decision was made in response to requests by rightists to restore the prewar Kigensetsu holiday and gave shape to nationalism in the form of law. Thus, postwar conservative administrations skillfully maintained a delicate balance between improving Asian relations and returning to tradition.

The same pattern applies to the administration of Fukuda’s father, former Prime Minister Fukuda Takeo, under whom Fukuda served as an aide. In 1978, the senior Fukuda significantly advanced “Japan-China reconciliation” by signing the Japan-China Peace and Friendship Treaty by placating rightist opponents. It was also around the same time that the Fukuda administration paved the way for the enactment of the Gengo (the name of a Japanese era) Law in 1979. This law, too, was established in response to fervent requests from rightists.

Emperor Akihito meeting with

South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun

After National Foundation Day and the Gengo Law comes the National Flag and Anthem Law, which was established in 1999. As it happens, South Korean President Kim Dae Jung and Chinese President Jiang Zemin both visited Japan around the same time during the previous year, prompting then Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo to incorporate Japan’s apologies for its past deeds in joint declarations. What I call the “law of next year” applies here as well.

It may be nothing more than a coincidence, but I happened to discover the “law of next year” while gazing over the chronology of events to prepare a manuscript for “Riberaru kara no Hangeki” (Counterattack from liberals) recently published by The Asahi Shimbun as part of the Asahi Sensho library. On the one hand is the trend to advance reconciliation based on denial and reflection of Japan’s prewar conduct. On the other hand is the trend to go back to traditional ways that could lead to affirmation of prewar Japan. The double face of postwar Japanese politics is symbolized by these two contradictory trends that have continued to exist as opposite sides of the same coin.

In other words, the repetition of “reconciliation” and “patriotism” has been a specialty of Liberal Democratic Party governments that can be likened to acrobatic stunts. In the past, the prime ministers’ Yasukuni visits had been regarded as one such acrobatic feat.

But now that the “enshrinement of Class-A war criminals” together with other war dead weighs too heavily, the prime minister can no longer maintain the balance of acrobatics. Despite such circumstances, Prime Minister Koizumi continues to stick to this stunt in defiance of booing by Asian neighbors.

When asked what qualities are needed to make the next prime minister at a news conference in Seoul, Nakasone replied at once: “The ability to break the deadlock of Asian diplomacy.”

The post-Koizumi game is starting to move in various places.

* * *

Wakamiya Yoshibumi heads The Asahi Shimbun’s editorial board. This column appeared in IHT/Asahi Shinbun, April 12, 2006. Posted on Japan Focus April 20, 2006.