From the Firing at Yeonpyeong Island to a Comprehensive Solution to the Problems of Division and War in Korea

Wada Haruki

The firing by North Korea on Yeonpyeong Island dealt an unprecedented blow to the national mood. Following the June 15, 2000 declaration by Kim Dae Jung and Kim Jong Il, the feeling that no state of war existed between North and South gripped the people of South Korea. But now, islanders and military personnel died as a result of the bombardment from the North in broad daylight, and houses and facilities were destroyed. South Korean people felt shock, fear and anxiety. It’s understandable that President Lee Myung-bak, who first warned against enlarging the situation, eventually decided to take counter measures. People of South Korea have to think about how to prevent the situation from worsening, while responding to this new situation. Moreover, people throughout the region need to reflect on this situation.

Although I’m a Japan-based researcher on North Korea, I’m no specialist in contemporary military affairs and there is much that I don’t understand. Still, I would like to address this situation.

First, let me examine the statement by the DPRK foreign ministry on the incident dated November 24, 2010. The statement calls the area surrounding the island, a “delicate area” and says that the North had asked the South to stop the planned bombardment. The North claimed that “because the island is located deep in our territory away from the military border, if target practice with live shells is conducted, then the shells, no matter which direction they are fired, will fall on our territorial sea.” Starting at 1 p.m. on November 23, South Korean forces fired several tens of shells toward the south, that is in the opposite direction from North Korea. But the shells landed, the North claims, on the territorial seas of the North. If North Korea failed to respond, South Korea might have sought to engage in subterfuge, claiming that this proved that the North recognized the area around the island as the territorial sea of the ROK. Therefore, the North “acted in self defense” by firing. This was the North’s claim.

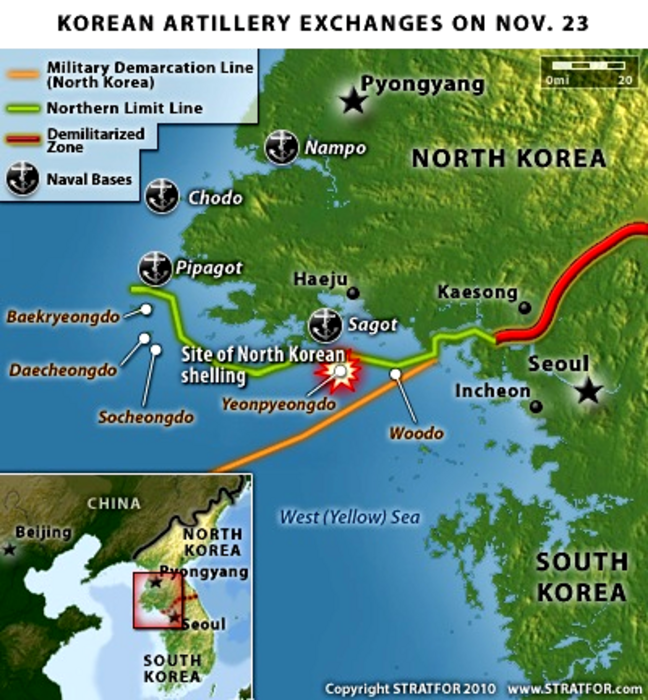

This statement came as a shock. The North admits that the island belongs to South Korea, but considers the surrounding sea to be the territorial sea of the North. What does this mean? I could not immediately understand it. So, I consulted an article by Lee Yonghi about the Northern Limit Line. The article was written after the military clash between the two navies that took place in June 1999 in the sea Northwest of the island. At that time, the South made unofficially announced that a DPRK naval vessel was sunk and twenty to thirty crew members died. According to the article, the Military Demarcation Line that the two sides had agreed upon for the West Sea in the 1953 ceasefire agreement of the Korean War was from the junction of the Han River and Yesong River to Udo Island. The article noted that the five islands [Yeonpyeong, Baekryeong, Daecheong, Socheong and Woodo], including Yeonpyeong, were to be placed under the military control of the Supreme Commander of the UN Army. Aside from this, no line was drawn in the area nor was any agreement made. In short, the Northern Limit Line is not a borderline that was stipulated and agreed upon between the two sides. Yeonpyeong is only four kilometers from North Korean territory. If South Korea claims that this island is its territory, the sea should then be divided at the center line of the four kilometers between the North’s land and Yeonpyeong island. The North, claiming the special character of the island and the twelve mile territorial rights on the basis of maritime law, seems to claim the area around the island as its territory.

If so, this maritime area is contested terrain, although Kim Jong Il’s November 4, 2007 declaration proposed creation of a West Sea special peace zone and setting up a joint fishery area and a peace area at sea. But after the idea proved to be an unreal dream (maboroshii) with the election of the Lee administration, tensions remained in this area.

Therefore, it’s not difficult to understand the logic, which is that the North cannot tolerate firing by the South from the island. However, it is still abnormal, that is, it is too rash to conclude that firing by South Korean forces to the South of the island constitutes an attack on the North’s own territorial sea, and, based on that understanding, to attack the island where people live together with military personnel. Why the leaders of North Korea, who have repeatedly emphasized that a peaceful environment is necessary to pave the way for the nation to become a great power by 2012 . . . why they made such an unusual decision . . . is a big question.

I think that the North Korean leadership believes that, given the situation, the ten year experience of North-South Korean embrace since the summit meeting of 2000 cannot continue.

Following the Pyongyang visit of President Kim Dae Jung in 2000, South Korean people felt great relief: the threat of war receded in the South, the North does not want war and pledges to end war. Good will toward, and interest in, North Korea grew among South Koreans. Many people visited the North and economic cooperation flourished in Kaesong.

|

Kim Dae Jung (left) and Kim Jong Il |

But as a result, I believe that South Koreans came to the realization that the North is so poor and backward as a country. This may be the origin of the feeling that the North is no longer frightening. Southerners may now feel that they want unification, but it’s okay not to unify for the time being. It’s enough to continue to provide a certain amount of aid to assure peace. The North-South embrace of ten years seems to have given South Koreans this kind of superiority and sense of relief.

However, at the same time, North Korean people begin to understand, on the basis of information on the South coming via South-North exchange and other channels, that South Korea with its glittering economy, is so advanced. The Kaesong industrial zone helps the North to earn wages, but it’s impossible to believe that the economy of the North will leap forward. It continues to lag behind the South and, at this rate, even with Kim Dae Jung’s pledge of aid, it appeared that the North would continue to be subordinate to the South. In this situation, the leadership of North Korea loses self-esteem and its malaise increases.

It may be that North Korea thinks that it has come to this because of the North-South embrace, which makes it impossible to open relations with either the US or Japan, limiting the North to economic relations with the South alone. The South has deep relations with Russia and China as well, and it is helping North Korea. The problem, however, is that North Korea came to have relations with South Korea without being able to open relations with the United States or Japan.

With the US, the North went so far as to send the number two leader, Marshal Jo Myong Rok, to visit Washington in 2000 and, following Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s visit to Pyongyang in that year, a US-North Korea summit seemed possible. But, with the appearance of President George W. Bush, everything was nullified. The North placed hopes on Pres. Obama, but these hopes were betrayed. Two former presidents, Clinton and Carter, visited the North, but nothing came of this. With Japan, the North invited Koizumi in 2002 and 2004, and meetings were held, but both times, the North’s hopes were dashed. Now the North is in the worst situation with Japan.

|

Marshel Jo and president Clinton at the White House |

No matter how much Japan punishes it, the North does not think that Japan will attack. However, when half a century passes without any agreement at all with the US, the North cannot escape fears of US attack. North Korea has not reached agreement with the US since the ceasefire of 1953, and the US is a government that is fighting wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. If it shows weakness toward the United States, they will be attacked. This is what North Korea believes. Therefore, while pursuing nuclear development, the North has proclaimed the goal of establishing a peace system (heiwa taisei).

The Yeonpyeong problem is a liability of the ceasefire system. It is a link in the peace system construction problem. The North will not just counterattack the South Korean military exercise but also press for the construction of a peace system with the US—this is perhaps the reason for the attack in the eyes of Kim Jong Il. However, such a decision is abnormal. It is abnormal for the North to fail to understand how strongly such a firing on the island would repel South Koreans. The attack could have the effect of demolishing the peace-oriented system that had been formed in the years since 2000. How could a North Korean leadership, which advances the slogan of looking toward 2012 to bring about a decisive change in economic construction and the life of the citizens, embark on so wild an action?

This reveals the dangerous potential that the Chairman of the Defense Committee, Kim Jong Il, can make a decision beyond our understanding. If so, efforts should be made to assure that there will be no misunderstanding in military affairs, and to make it possible to negotiate. Clearly military pressure is not sufficient to prevent further reckless action.

In August 2009 I worked on a joint statement on Korea by South Korean, American and Japanese intellectuals on averting crisis in Northeast Asia. Our first item was a strong demand that “President Obama and Chairman Kim Jong-il to return to a course of dialogue and negotiation, and take steps to reduce tensions. We urge that they immediately initiate a search for US-North Korea negotiation, whether by public or non-public, bilateral or multilateral means, including by the dispatch of a special (US) envoy. They must make it clear that the goal of the negotiation is to normalize the relationship between the two countries, end the state of war, and denuclearize the Korean peninsula. As a first step, they must declare that they recognize each other’s sovereignty. On humanitarian grounds, Washington should resume its humanitarian assistance to the North, and Pyongyang should take steps to return the two American reporters detained in North Korea.” Today I must repeat this request.

Second, it is desirable that the countries of this area conduct multinational discussions. China is calling for talks among the countries related to the Six-Party Talks. But those talks were directly linked to nuclear issues. Wouldn’t it be better to broaden the agenda? In last year’s statement we suggested that “a Northeast Asian disarmament conference should be convened to lower the level of regional military preparations, including conventional arms as well as weapons of mass destruction.” Further, it would be helpful to hold a meeting that will handle the maritime peace of the area and the peace of the island and place on the table for discussion the problems of the Senkaku islands, the five islands in the West Sea, Dokdo (Takeshima), and the northern four islands.

Last, I think that Japan should act between North and South, and between Japan and the US. At present, the Japanese administration is in the worst situation. For the present, it can say nothing other than that Japan will cooperate with South Korea and the United States. However, Japan promises to solve the problem of kidnapping. In order to push toward a solution, Japan must negotiate. If negotiations are open, then Japan can persuade North Korea.

North and South have to be tense for a while. It is natural that the South cannot return to a normal relationship so long as the North doesn’t apologize. Therefore, it would be helpful to the South if Japan conducts the negotiation.

Wada Haruki wrote this article for the Kyunghyang Daily, December 7, 2010. The 2009 statement quoted above was “Averting Catastrophe in Northeast Asia: An Appeal to the United States, North Korea (DPRK) and Other Nations in the Region.”

Wada Haruki is Emeritus Professor of the Institute of Social Science, Tokyo University and a specialist on Russia, Korea, and the Korean War. His many books include Chosen Senso zenshi (A Complete History of the Korean War), Kita Chosen – Yugekitai kokka no genzai (North Korea –Partisan State Today), and Dojidai hihan – Nicho kankei to rachi mondai (Critique of Our Own Times – Japan-North Korea Relations and the Abduction Problem).

Recommended citation: Wada Haruki, “From the Firing at Yeonpyeong Island to a Comprehensive Solution to the Problems of Division and War in Korea,” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 8 Issue 50 No 4 – December 13, 2010.

|

This article is part of a series commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the Korean War. Other articles on the sixtieth anniversary of the US-Korean War outbreak are: • Mark Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War. • Steven Lee, The United States, the United Nations, and the Second Occupation of Korea, 1950-1951. • Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas. • Han Kyung-koo, Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On.

Additional articles on the US-Korean War include: • Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism. • Kim Dong-choon, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War • Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War. • Sheila • Tim Beal, Korean • Nan Kim |